Negative Organizations and [Negative] Powerful Relationships and How They Work against Innovation—Perspectives from Millennials, Generation Z and Other Experts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“It is critical to understand both the multifaceted nature of workplace politics and its potential detrimental effects.”[1] (pp. 1900–1901).

2. A Look at Gaps in the Literature Regarding Negative and Positive Organizations

“Politics is one of the most pervasive, yet negative attributes of modern workplaces”

3. Methodology

4. The Case of Nokia

“More than seven years before Apple Inc. rolled out the iPhone, the Nokia team showed a phone with a color touch screen set above a single button. The device was shown locating a restaurant, playing a racing game and ordering lipstick. In the late 1990s, Nokia secretly developed another alluring product: a tablet computer with a wireless connection and touch screen–all features today of the hot-selling Apple iPad”[25].

5. Discussion of the Interview Results

“Of course, negative organizations exist, and the status quo can impose itself and prevail over innovation.”(interviewee Pedro Pereira).

“Negative organizations are a reality. Often organizations, instead of focusing on global strategies, which aim for improvement and success, also self-annihilate by looking inward and expending energy in trying to annihilate internal rivals and their support systems; which will be greatly reflected in the future performance of organizations. Therefore, according to this dimension, we can admit clearly that, unfortunately, negative organizations are a fact and a reality.”(interviewee Emídio Gomes).

“... an organisation that... lives in the present, mortgages the future, does not want to improve, does not distribute its “results” evenly among its stakeholders.

There are as many types of negative companies as there are combinations of neglecting stakeholders. For example, a company that “diverts” all its results to shareholders tends to treat its employees worse and to enter a negative spiral of high turnover.

But a company that ignores shareholder rewards, diverting all the results to the employees, will find it difficult to invest, which takes away agility and growth potential, which will be bad for the employees in the long run.

A borderline case is the Civil Service, which long ago forgot its customers, becoming (almost) only an organisation that guarantees jobs to people (at all levels...).

By the way, it is easy (and simplistic) to look at the negativity or positivity of an organisation from the employees’ point of view, and to classify an organisation as “positive” when it focuses on its employees.

The example of the Civil Service (whose reason for existence, in a large percentage, are its employees) is paradigmatic of how this vision is narrow, and the positive company takes into account ALL its stakeholders (even Planet Earth...).”

“The environment involves creativity. In a “heavy” environment you will not have much chance to innovate. You will be: “rowing against the tide”. People who try to innovate in a negative organization are looked upon differently, depreciatively. They are set aside, ostrasized, thought to be crazy and not contributing to the firm...”.

“Though not formally being like this, small power groups often exist in organizations, some more hidden than others (as mentioned, they are formally not very visible), but are power groups which are felt in operational terms, and that considerably condition global performance; there is clearly a level of negative organization in institutions; more or less visible, according to their dimension; and as a function of their situation and location [...] which, when added up, cause damage to the global strategy.”

“... an organisation that acts in order to promote its own growth and sustainability and that knows how to balance the distribution of its “results” among its main stakeholders: customers, employees, shareholders and partners, safeguarding the resources necessary for growth. It is a company that sees itself in the future and knows how to moderate the temptations to mortgage it for a better, or easier, present.”

“In a positive firm there is a meritocracy, the best collaborator wins, gets promoted... In a positive firm those who contribute more to the firm with innovative ideas and think outside-the-box get recognized for that, and not ostrasized for it and put aside for doing good things. Those who do not align with “the system” of a firm that functions badly [are good employees].”

“Positive organizations exist. The great message which has to be passed is that these small power groups should be fought, with serenity, but with firmness, so that they do not superimpose themselves too much on the performance of the group, which has to be positive. Otherwise, it will be the organization which will be badly affected over time. When the power of the negative organization excessively overlays the global group, it is the organization and institution that will suffer. Often there are not more dramatic consequences from the point of view of the institution itself when we are witnessing some protection in the public sector; contrarily, when we are subject to [free] market forces, the organization may disappear.”

“My view of the business market is very “Darwinian”. The most “competitive” companies are the most “adapted”, and adaptation implies change, whenever the ecosystem changes. For a certain company, change is always innovating, even when the change has already been made by other companies, and it is the last to change. So, from the company’s point of view, change is critical to keep up with the market (and to compete), and by definition, innovating is also, even if they are small changes in processes, for example locally optimising something (what is usually called Incremental Innovation or Continuous Improvement).

But, even if it is an innovative company, it is important to understand that the mix of betting on innovation (disruption vs. optimisation) can vary a lot according to the life cycle of the company and the market.

At one extreme, we have companies that are founded to take advantage of a potentially disruptive innovation. At this extreme, the answer is obvious...

At the other extreme, we have a mature company in a mature market. In this case, and in the short term, the influence of disruptive innovation is low, and the focus tends to be on local process optimisation (and which is not, today, typically classified as Innovation, being rather classified as Continuous Improvement and under the remit of Quality, whose main attribution is to ensure that the defined processes are executed according to tolerances and to produce evidence of this...).”

“Organizational culture is very important. You feel it straight away in any firm you enter. An individual with experience notices the organizational culture right away. It is “in the air”. It is hard to explain in words. There is no need to speak to a lot of people... it is a question of seeing the environment, seeing how people look. Then by talking to certain people you will know. You do not need to ask a lot of questions to learn about the environment of a firm. A firm environment involves a lot of things–promotions, meritocracy, career advancement...”

“It is very, very difficult for a leader to have an effect on the organizational culture, we are talking about only marginal gains. Marginal and temporary gains, as there is always an organizational culture installed with some resistance to change. It is curious that people say, they complain, that they want and like change. They like that. Albeit when they are confronted with specific change decisions, they resist, in a very accentuated way. There is an enormous resistance to change. Everywhere, but especially in Portugal, where it is very evident. In Portugal there are little options and ways to change situations... The resistance to change here is very strong and that resistance is very cultural, very strong.”

6. A Survey on Negative and Positive Organizations Involving Millennials

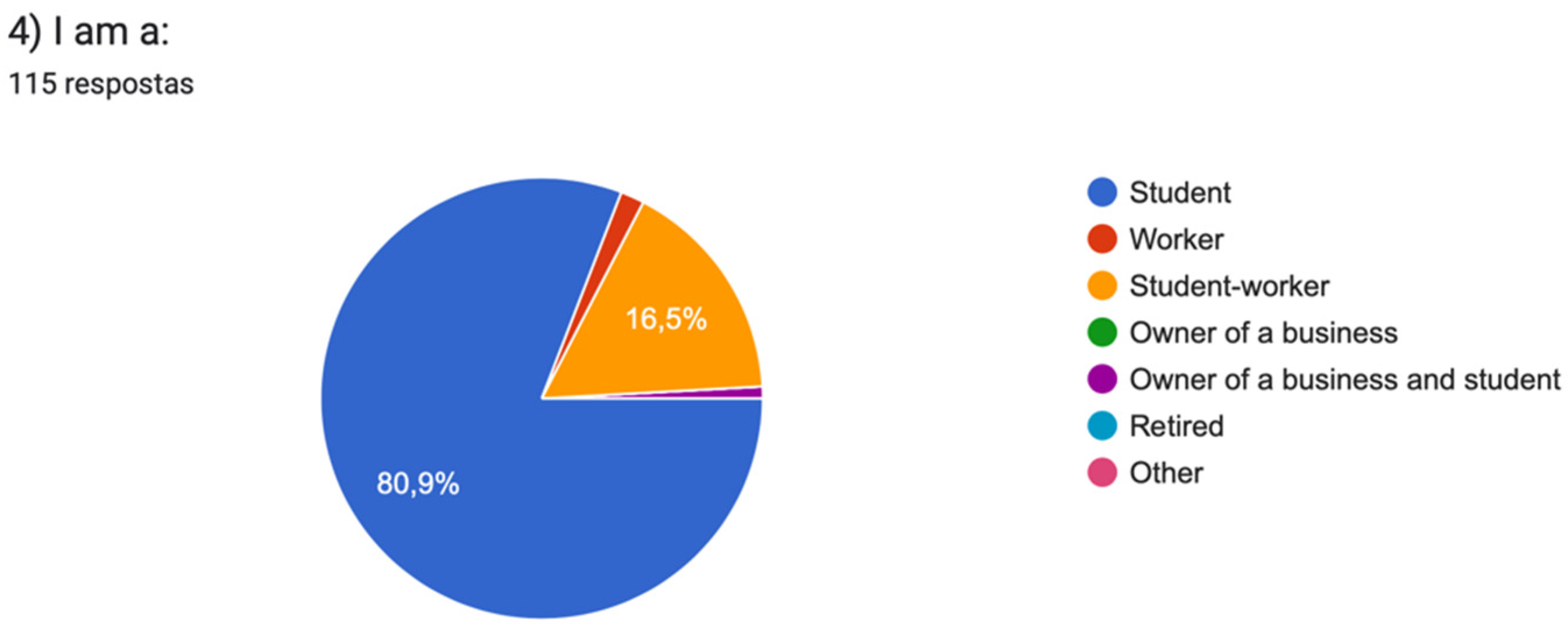

7. A Survey on Negative and Positive Organizations Involving Generation Z

8. Discussion and Conclusions

“Openness to experience might stimulate [... the] employees’ ability to address the negative consequences of covert political behavior”[14] (p. 194).

“Knowledge of oneself (capabilities and personality) is essential in combatting anti-innovators (note that one may change and improve, by learning, over time). Emotional intelligence (ability to self-manage oneself, emotionally, including how one communicates and empathizes with others), not surprisingly, is very important. Finally, showing and feeling anxious is bad in the fight against anti-innovators.”[34] (p. 83).

“Envy can act as a barrier to innovation by triggering counterproductive behaviors such as ostracism and a decrease in predisposition to innovative behaviors, either due to innovative individuals prematurely exiting the organization or due to them lessening/dampening their innovativeness to avoid the negative consequences”[35].

9. Suggestions for Future Research and Limitations of the Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Castanheira, F.V.d.S.; Sguera, F.; Story, J. Organizational Politics and its Impact on Performance and Deviance Through Authenticity and Emotional Exhaustion. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. Michael Porter on Strategic Innovation—Creating Tomorrow’s Advantages. Disruptor League. 29 December 2011. Available online: https://www.disruptorleague.com/blog/2011/12/29/michael-porter-on-strategic-innovation-creating-tomorrows-advantages/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Negative Organizations and How to Overcome Them—Fighting to Promote Innovation and Change; Sílabas & Desafios: Faro, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, C.M.; Schell, M.S. Managing Across Cultures—The Seven Keys to Doing Business with a Global Mindset; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.K.; Rutherford, M.A.; Kolodinsky, R.W. Perceptions of Organizational Politics: A Meta-analysis of Outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2008, 22, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. A Dual Conception of Narcissism: Positive and Negative Organizations. Psychoanal. Q. 2002, 71, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, A.; Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A. When and why do negative organization-related career shocks impair career optimism? A conditional indirect effect model. Career Dev. Int. 2021, 26, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Z.S.; Manning, S.G.; Weston, J.W.; Hochwarter, W.A. All roads lead to well-being: Unexpected relationships between organizational politics perceptions, employee engagement, and worker well-being. Res. Occup. Stress Well Being 2017, 15, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. Organizational climate: Individual preferences and organizational realities revisited. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Hu, D.-C.; Huang, Y.-C. Employee emotional intelligence, organizational citizen behavior and job performance: A moderated mediation model investigation. Empl. Relations 2022, 44, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, F.; Hassan, H. A strategic mismatch: Organizational politics and creative propensity. Rev. Int. Bus. Strat. 2018, 28, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glor, E.D.; Ewart, G.A. What happens to innovations and their organizations? Piloting an approach to research. Innov. J. 2016, 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Yuan, Q.; Hu, K.; Huang, R.; Liu, Y. Employees’ emotional intelligence and innovative behavior in China: Organizational political climate as a moderator. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2020, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Bouckenooghe, D. Mitigating the Harmful Effect of Perceived Organizational Compliance on Trust in Top Management: Buffering Roles of Employees’ Personal Resources. J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, G.R.; Kacmar, K.M. Perceptions of organizational politics. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P. Doing Research in Business and Management—An Essential Guide to Planning Your Project, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Adams, T.E.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2011, 12, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dimock, M. Defining Generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z Begins. Pew Research Center. 17 January 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Cooper, S.A. Understanding Business Statistics—An Active-Learning Approach; The Guernsey Press: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H. Misbehaving—The Making of Behavioural Economics; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Estêvão, C.M.P.V. O Impacto da Emergência dos Smartphones: Um Estudo de Caso da Nokia e da Samsung. [The Impact of Smartphone Emergence: A Case Study of Nokia and Samsung]. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Economics, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2015. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/81350/2/37123.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Lebre, I.; Nogueira, A.; Gonçalves, R. Success, failure, marketing and innovation—The case of Nokia. Rev. Ibérica Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2020, E34, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Troianovski, A.; Grundberg, S. Nokia’s Bad Call on Smartphones. Wall Str. J. 2012. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304388004577531002591315494 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Microsoft Sells Nokia Feature Phones Business. BBC News, 18 May 2016. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-36320329(accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Wollaston, S. The rise and fall of Nokia review—Fascinating insight into the Finnish, and now finished, tech firm. The Guardian, 10 July 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/jul/10/the-rise-and-fall-of-nokia-review-fascinating-insight-into-the-finnish-and-now-finished-tech-firm(accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Collins, J.; Porras, J.I. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies; Harper Business Essentials: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, V. 25 Need to Know Strategy Tools; FT Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rothaermel, F.T. Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; The Free Press: Hong Kong, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Organizational Culture; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Walter, C.E. Innovators and Anti-innovators in the Digital Era—The Persecution of the Innovative by the Less Innovative. In Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, A., Adeli, H., Dzemyda, G., Moreira, F., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.E.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. An exploratory study on the barriers to innovative behavior: The spiteful effect of envy. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2022, 35, 936–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, H.H.; Grøn, C.H.; Kjeldsen, A.M. Leadership Matters, But So Do Co-Workers: A Study of the Relative Importance of Transformational Leadership and Team Relations for Employee Outcomes and User Satisfaction. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2022, 42, 614–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P.-L.; Moisan, L.; Lagacé, D. Seizing the opportunity: The emergence of shared leadership during the deployment of an integrated performance management system. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme (x 5) | Evidence from the Interviews |

|---|---|

| Negative organization | “Negative organizations are a reality. Often organizations, instead of focusing on global strategies, which aim for improvement and success, also self-annihilate by looking inward and expending energy in trying to annihilate internal rivals and their support systems; which will be greatly reflected in the future performance of organizations.” (Emídio Gomes). “Of course, negative organizations exist, and the status quo can impose itself and prevail over innovation.” (Pedro Pereira). |

| Positive organization | “... an organization that acts in order to promote its own growth and sustainability... It is a company that sees itself in the future and knows how to moderate the temptations to mortgage it for a better, or easier, present.” (João Ranito). “In a positive firm there is a meritocracy, the best collaborator wins, gets promoted...” (Pedro Pereira). |

| Organizational culture | “The influence of organizational culture as regards competitiveness is total. A company’s culture determines its competitive potential, as it also determines the comfortable balance point between ‘agility’ and ‘optimization’” (João Ranito). |

| Innovation | Let us be reminded that marketing innovation is also a form of innovation, which Apple is very good at, according to interviewee João Ranito. Product innovation is not the only type of innovation in industry today. |

| Resistance to change | “... there is always an organizational culture installed with some resistance to change. It is curious that people say, they complain, that they want and like change. They like that. Albeit when they are confronted with specific change decisions, they resist, in a very accentuated way... Everywhere, but especially in Portugal, where it is very evident. In Portugal there are little options and ways to change situations...” (Emídio Gomes). |

| Are Organisations Negative or Positive? | Organiz ations are Negative | Organizations are Positive | There are Negative and Positive Organizations | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 (54.31%) | 35 (30.17%) | 18 (15.52%) | 116 |

| Negative | Positive | Both | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 18 | 25 | 10 | 53 |

| Women | 45 | 10 | 8 | 63 |

| Total | 63 | 35 | 18 | 116 |

| O | E | (O − E) | (O − E)2 | (O − E)2/E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 28.78 | −10.78 | 116.21 | 4.038 |

| 25 | 15.99 | 9.01 | 81.18 | 5.077 |

| 10 | 8.22 | 1.78 | 3.17 | 0.386 |

| 45 | 34.22 | 10.78 | 116.21 | 3.396 |

| 10 | 19.01 | −9.01 | 81.18 | 4.27 |

| 8 | 9.78 | −1.78 | 3.17 | 0.324 |

| Sum | 17.491 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Negative Organizations and [Negative] Powerful Relationships and How They Work against Innovation—Perspectives from Millennials, Generation Z and Other Experts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417018

Au-Yong-Oliveira M. Negative Organizations and [Negative] Powerful Relationships and How They Work against Innovation—Perspectives from Millennials, Generation Z and Other Experts. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):17018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417018

Chicago/Turabian StyleAu-Yong-Oliveira, Manuel. 2022. "Negative Organizations and [Negative] Powerful Relationships and How They Work against Innovation—Perspectives from Millennials, Generation Z and Other Experts" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 17018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417018

APA StyleAu-Yong-Oliveira, M. (2022). Negative Organizations and [Negative] Powerful Relationships and How They Work against Innovation—Perspectives from Millennials, Generation Z and Other Experts. Sustainability, 14(24), 17018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417018