Afforestation of Transformed Savanna and Resulting Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Zaria (Nigeria)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

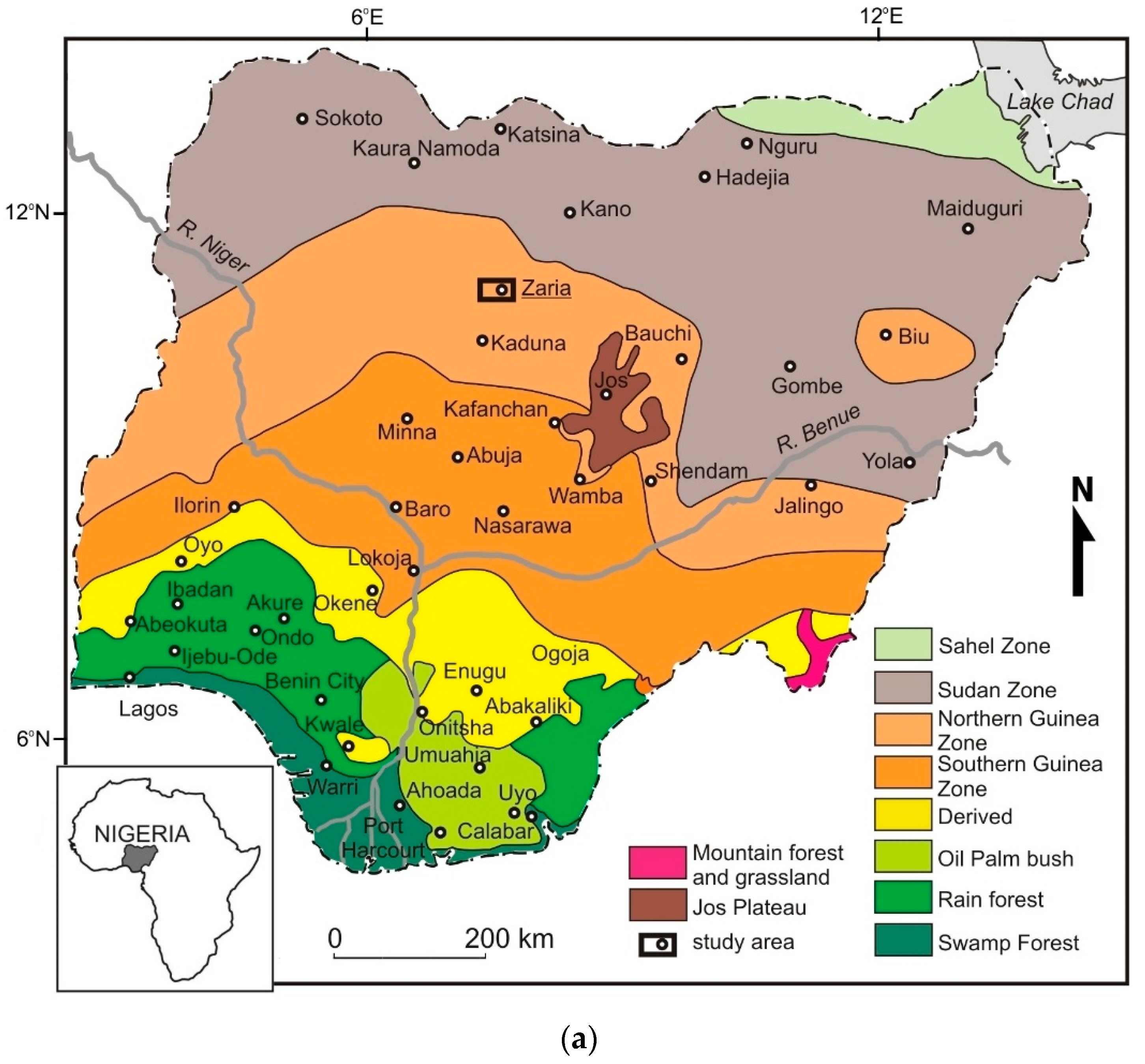

2. Study Area

2.1. Location

2.2. Tree Cover and Environmental Problems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Field Work

3.2. Land-Use Map

3.3. Estimation of Vegetation Cover from Landsat Images

where rb = RED − γ × (BLUE − RED); γ = 1

4. Results

4.1. Tree Cover and Other Spatial Development Elements on the Land-Use Map

- Housing districts of the university campus: area A, constructed before 1964, formerly belonging to St. Peter’s College and the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, and housing areas BZ, F, E, G and G-Extension, ABU Qrts-3 and the Waterworks Quarters (constructed after 1966); most of them are densely wooded;

- ABU teaching and administration areas, other facilities (Shika Hospital, Centre for Energy Research and Training), and some new developments (built after 2008);

- Areas marked as Rv are the parts of the land in which relics of original vegetation have been found, representing typical Guinea savanna, partly covering stabilized (inactive) areas degraded by gully erosion;

- Areas marked as Pl are plantations, which are described in Table 2; it was estimated that in the years from 2000 to 2008 approximately 20,000 trees were planted over a total area of approximately 159 ha, which gives the mean figure of 2500 trees per year. Figure 5 shows the examples of afforested areas of the ABU land. The total area planted with mahogany is 67.51 ha, mango 8.27 ha, cashew 8.99 ha and eucalyptus or eucalyptus together with neem 58.45 ha;

- Areas of new plantings (after 2008), marked as PLn, observed on the high-resolution Google Earth image in 2020, of which total area is approximately 0.6 km2 (60 ha) (Table 3). In the period from 2008 to 2020, the area planted with mahogany was 3.11 ha, mahogany together with other species (black plum, date palm, oil palm, white teak) 16.69 ha, black plum 4.4164 ha, mango 21.73 ha, white teak 8 ha, guava 1.663 ha, guava mixed with other species (cashew, mango and eucalyptus) 2.63 ha, eucalyptus 1.7485 ha;

- Areas marked as Gl are areas degraded by erosion (badlands, gully erosion). Their total area is 6.1619 km2 (616.19 ha), of which 3.3 km2 (330 ha) are within university grounds; this accounts for approximately 10.9% of the area owned by the university.

4.2. Tree Cover Estimated from Landsat Images

5. Discussion

5.1. Common African Environmental Problems also Present in the ABU Area

5.2. Tree Cover Extent and Land Cover State Derived from Satellite Data

- It is open source;

- It provides the latest satellite imagery;

- It has high spatial resolution;

- Popular software have provided tools for easy and efficient acquisition and use of Google Earth images;

- It provides images acquired at different times, which helps to detect land-use changes [56];

- Possibility of fast browsing coupled with digitization tools helps to directly export processing results to the local GIS [58].

5.3. Single-Species and Mixed Planting Systems

- Mechanical (shielding individual specimens with tube, mesh and spiral trunk protectors, fencing and shelter belts of fast-growing species);

- Biological (application of certain living organisms to reduce the populations of others, e.g., insect pests and pathogenic fungi);

- Chemical (animal repellents, fungicides, insecticides, etc.);

- Integrated measures.

5.4. Extending the Planting Initiative in the Rural ABU Neighborhood

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. How Are the World’s Forests Changing? 2nd ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i4793e/i4793e.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Adesina, J.B. Global Forest Resources Assessment. Country Report Nigeria; Forestry Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/8968-08a7263cd02b0795f7ead548824725c86.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Amosun, O.O.; Adedoyin, O.S. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010. Country Report Nigeria; Forestry Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/al586E/al586E.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Adedoyin, O.S.; Aluko, S.O.; Olabode, M.A.; Ajibola, A.A.; AJagun, E.O.; Ajakaye, O.C. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. Country Report Nigeria; Forestry Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/az293e/az293e.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Fleischer, L.R.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C.; Alewell, C.; Panagos, P. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boardman, J.; Foster, I.L.; Favis-Mortlock, D. A 13-year record of erosion on badland sites in the Karoo, South Africa. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 1964–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiage, L.M. Perspectives on the assumed causes of land degradation in the rangelands of Sub-Saharan Africa. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2013, 37, 664–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Third National Communication (TNC) of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); Federal Ministry of Environment: Abuja, Nigeria, 2020. Available online: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/NationalReports/Documents/187563_Nigeria-NC3-1-TNC%20NIGERIA%20-%2018-04-2020%20-%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Derrick, J. The Great West African Drought, 1972–1974. Afr. Aff. 1977, 76, 537–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, E.O. A comprehensive approach to drought and desertification in northern Nigeria. Nat. Hazards 1993, 8, 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.; Tucker, C.J.; Sy, H. Tree density and species decline in the African Sahel attributable to climate. J. Arid Environ. 2012, 78, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mouhamed, L.; Traore, S.B.; Alhassane, A.; Sarr, B. Evolution of some observed climate extremes in the West African Sahel. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2013, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olaniyi, O.A.; Ojekunle, Z.O.; Amujo, B.T. Review of climate change and its effect on Nigeria ecosystem. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. Open Access Int. J. 2013, 1, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eniolorunda, N.B.; Mashi, S.A.; Nsofor, G.N. Toward achieving a sustainable management, characterization of land use/land cover in Sokoto Rima floodplain, Nigeria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 19, 1855–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, F.; Molini, V.; Azad, M. A mapping framework to characterize land use in the Sudan-Sahel region from dense stacks of Landsat data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falaki, M.A.; Ahmed, H.T.; Akpu, B. Predictive modeling of desertification in Jibia Local Government area of Katsina State, Nigeria. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2020, 23, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badamasi, M.M.; Yelwa, S.A.; Abdul Rahim, M.A.; Noma, S.S. NDVI threshold classification and change detection of vegetation cover at the Falgore Game Reserve in Kano State, Nigeria. Sokoto J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 2, 174–194. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/4365548/NDVI_threshold_classification_and_change_detection_of_vegetation_cover_at_Falgore_Game_Reserve_in_Kano_State_Nigeria (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Suleiman, M.S.; Wasonga, O.V.; Mbau, J.S.; Elhadi, Y.A. Spatial and temporal analysis of forest cover change in Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol. Process. 2017, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Great Green Wall Implementation Status and Way Ahead to 2030. Advanced Version; United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, Climatekos GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://catalogue.unccd.int/1551_GGW_Report_ENG_Final_040920.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Oni, P.I. State of Forest Genetic Resources in the Dry North of Nigeria; Forest Genetic Resources Working Papers 16E; Forest Resources Division FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ab392e/ab392e.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Ajayi, S.S.; Milligan, K.R.N.; Ayeni, J.S.O.; Afolayan, T.A. A management programme for Kwlambana Game Reserve, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Biol. Conserv. 1981, 20, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International. Important Bird Areas Factsheet; Kamuku. 2021. Available online: http://www.birdlife.org (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Udo, R.K. Geographical Regions of Africa; Morrison and Gibb Ltd.: London, UK; Edinburgh, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Digital Elevation—Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Global. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm-1 (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Schoeneich, K. Report on Result of Measurement of the Remaining Storage in Kubanni Impounding Reservoir and Proposal for Upgrading the Environment in Kubanni Drainage Basin; Unpublished Report; Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Odihi, J. Deforestation in afforestation priority zone in Sudano-Sahelian Nigeria. Appl. Geogr. 2003, 23, 227–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline-Cole, R.; Maconachie, R. Wood energy interventions and development in Kano, Nigeria; A longitudinal, ‘situated’ perspective. Land Use Policy 2015, 52, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baba, A. Integrated Water Resources Management Plan for Ahmadu Bello University. M.Sc. Report; The Department of Geology, Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Google Earth Pro Inc. v. 7.3.4.8248. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- U.S. Geological Survey. Earth Explorer, LE07_2000-04-28_Level 1C1, LC08_2020_04_27. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hall, F.G.; Sellers, P.J.; Marshak, A.L. The interpretation of spectral vegetation indexes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, S.M.; Anyamba, A.; Tucker, C.J. Recent trends in vegetation dynamics in the African Sahel and their relationship to climate. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochege, F.U.; George, R.T.; Dike, E.C.; Okpala-Okaka, C. Geospatial assessment of vegetation status in Sagbama oilfield environment in the Niger Delta region, Nigeria. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2017, 20, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, J.R.G.; Justice, C.O. Analysis of the dynamics of African vegetation using the normalized difference vegetation index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1986, 7, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Pattey, E.; Zarco-Tejadad, P.J.; Strachan, I.B. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Ju, W.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Fan, W. Using vegetation indices and texture measures to estimate vegetation fractional coverage (VFC) of planted and natural forests in Nanjing city, China. Adv. Space Res. 2013, 51, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochet, H. Agrarian dynamics, population growth and resource management, the case of Burundi. GeoJournal 2004, 60, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamo, J.; Schaldach, R.; Koch, J.; Kölking, C.; Lapola, D.; Priess, J. Evaluation of an integrated land use change model including a scenario analysis of land use change for continental Africa. Environ. Model. Softw. 2011, 26, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Dawson, T.P.; Macdiarmid, J.I.; Matthews, R.B.; Smith, P. The impact of population growth and climate change on food security in Africa, looking ahead to 2050. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, L.C. Is land being degraded? A multi-scale investigation of landscape change in southwestern Burkina Faso. Land Degrad. Dev. 1999, 10, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay, D.; Bonkoungou, E.; Chamshama, S.A.O.; Chikamai, B. Rehabilitation of Degraded Lands in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons Learned from Selected Case Studies; Forestry Research Network for Sub-Saharan Africa (Fornessa), International Union of Forest Research Organizations: Vienna, Austria, 2004; Available online: https://fornis.net/node/249 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Usman, B.A.; Adefalu, L.L. Nigerian forestry, wildlife and protected areas: Status report. Biodiversity 2010, 11, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiran, G.A.B.; Kusimi, J.M.; Kufogbe, S.K. A synthesis of remote sensing and local knowledge approaches in land degradation assessment in the Bawku East District, Ghana. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 14, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemeobo, G.J. The Human Causes of Forest Depletion in Nigeria. Environ. Conserv. 1988, 15, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilruth, P.T.; Hutchinson, C.F. Assessing Deforestation in the Guinea highlands of West Africa using Remote Sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1990, 56, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Pouliot, M.; Treue, T.; Obiri, B.D.; Ouedraogo, B. Deforestation and the limited contribution of forests to rural livelihoods in West Africa: Evidence from Burkina Faso and Ghana. Ambio 2012, 41, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubréville, A.M.A. The Disappearance of the Tropical Forests of Africa. Fire Ecol. 2013, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huber, S.; Fensholt, R.; Rasmussen, K. Water availability as the driver of vegetation dynamics in the African Sahel from 1982 to 2007. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2011, 76, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A. Water scarcity and other significant challenges for South Africa. In Freshwater Challenges of South Africa and Its Upper Vaal River Springer Water; Springer International Publishing: Zürich, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, N.; Coulibaly, T.; Mpakama, Z.; Savané, I. The impact of climate change on water resource availability in a trans-boundary basin in West Africa, the case of Sassandra. Hydrology 2018, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igboanugo, A.B.I.; Omijeh, J.E.; Adegbehin, J.O. Pasture floristic composition in different Eucalyptus species plantations in some parts of northern Guinea savanna zone of Nigeria. Agrofor. Syst. 1990, 12, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayala, J.; Sanou, J.; Teklehaimanot, Z.; Kalinganire, A.; Ouédraogo, S.J. Parklands for buffering climate risk and sustaining agricultural production in the Sahel of West Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barau, A.S.; Kafi, K.M.; Sodangi, A.B.; Usman, S.G. Recreating African biophilic urbanism, the roles of millennials, native trees, and innovation labs in Nigeria. Cities Health 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooth, S. Virtual globes: A catalyst for the re-enchantment of geomorphology? Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2006, 31, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, B. The value of Google Earth™ for erosion mapping. Catena 2016, 143, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, U.; Denham, R.; Tindall, D. Gullies, Google Earth and the Great Barrier Reef, a remote sensing methodology for mapping gullies over extensive areas. In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Science, XXII ISPRS Congress, Melbourne, Australia, 25 August–1 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malarvizhi, K.; Vasantha Kumar, S.; Porchelvan, P. Use of high resolution Google Earth satellite imagery in landuse map preparation for urban related applications. Procedia Technol. 2016, 24, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.C.; Kuchma, O.; Krutovsky, K.V. Mixed-species versus monocultures in plantation forestry: Development, benefits, ecosystem services and perspectives for the future. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 15, e00419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jactel, H.; Menassieu, P.; Vetillard, F.; Gaulier, A.; Samalens, J.C. Tree species diversity reduces the invasibility of maritime pine stands by the bast scale, Matsucoccus feytaudi (Homoptera: Margarodidae). Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.D.; Okabe, K.; Parrotta, J.A.; Brockerhoff, E.; Jactel, H.; Forrester, D.I.; Taki, H. Biodiversity and ecosystem services, lessons from nature to improve management of planted forests for REDD-plus. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 2613–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, M.; Bongers, F.; Martinez-Ramos, M.; Poorter, L. The importance of biodiversity and dominance for multiple ecosystem functions in a human-modified tropical landscape. Ecology 2016, 97, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jactel, H.; Bauhus, J.; Boberg, J.; Bonal, D.; Castagneyrol, B.; Gardiner, B.; Gonzalez-Olabarria, J.R.; Koricheva, J.; Meurisse, N.; Brockerhoff, E.G. Tree diversity drives forest stand resistance to natural disturbances. Curr. For. Rep. 2017, 3, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hérault, B.; N’Guessan, A.K.; Ouattara, N.; Ahoba, A.; Bénédet, F.; Coulibaly, B.; Louppe, D. The long-term performance of 35 tree species of sudanian West Africa in pure and mixed plantings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 468, 118171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E. Population variation in root grafting and a hypothesis. Oikos 1988, 52, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B. Biogrupy drzew w lesie naturalnym: Czy prof. Włoczewski miał rację? Sylwan 2004, 7, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Quer, E.; Baldy, V.; DesRochers, A. Ecological drivers of root grafting in balsam fir natural stands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 475, 118388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, B.D.; Carsky, R.J. Multiple purpose tree use by farmers using indigenous knowledge in sub-humid and semiarid northern Nigeria. For. Trees Livelihoods 2001, 11, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifanou, V.G.; Ousmane, C.; Gauthier, B.; Brice, S. Traditional agroforestry systems and biodiversity conservation in Benin (West Africa). Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 82, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo-Koné, S.; Kaboré-Zoungrana, C.Y.; Ledin, I. Important characteristics of some browse species in an agrosilvopastoral system in West Africa. Agrofor. Syst. 2007, 74, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, K. Analysis of Agro forestry Farmers (Tree-Planting) in Giwa Local Government Area, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria, 2011. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ANALYSIS-OF-AGRO-FORESTRY-FARMERS-(TREE-PLANTING)-Usman/0341899e67e2e3e1c425292caa8a342b9c5793a1 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Tenuche, M.S.; Ifatimehin, O.O. Resource conflict among farmers and Fulani herdsmen: Implications for resource sustainability. Afr. J. Pol. Sci. Int. Relat. 2009, 3, 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Halliru, S.L. Security implication of climate change between farmers and cattle rearers in Northern Nigeria: A case study of three communities in Kura Local Government of Kano State. In Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation; Leal, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dimelu, M.U.; Salifu, D.E.; Enwelu, A.I.; Igbokwe, E.M. Challenges of herdsmen-farmers’ conflict in livestock production in Nigeria, Experience of pastoralists in Kogi State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 8, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awazi, N.P.; Avana-Tientcheu, M.-L. Agroforestry as a sustainable means to farmer–grazier conflict mitigation in Cameroon. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 94, 2147–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest Class | 1977 | 1990 | 1994 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (1000 ha) | |||||||

| Primary forest | 2623 | 1556 | 1228 | 736 | 326 | 54 | 20 |

| Planted forest (productive plantations) | 164 | 251 | 276 | 316 | 349 | 382 | 420 |

| Other naturally regenerated forest | 19,772 | 15,427 | 14,090 | 12,085 | 10,414 | 8659 | 6553 |

| Total forest | 22,559 | 17,234 | 15,594 | 13,137 | 11,089 | 9095 | 6993 |

| Total forest and other wooded land | not available | 26,951 | not available | 20,039 | 16,584 | 13,129 | not available |

| Denotation of Plantations on the Land-Use Map in Figure 4 | Prevalent Tree Type | Surface Area | Coordinates of the Central Point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | ha | |||

| Pl-1 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.2867 | 28.67 | 11°09′25.24″ N, 7°38′41.62″ E |

| Pl-2 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.2365 | 23.65 | 11°09′02.85″ N, 7°38′45.42″ E |

| Pl-3 | mango Mangifera indica | 0.08274 | 8.274 | 11°08′36.07″ N, 7°38′59.76″ E |

| Pl-4 | cashew Anacardium occidentale | 0.08997 | 8.997 | 11°08′34.56″ N, 7°39′15.15″ E |

| Pl-5 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.1463 | 14.63 | 11°08′49.49″ N, 7°39′36.98″ E |

| Pl-6 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.005612 | 0.5612 | 11°08′53.77″ N, 7°38′33.12″ E |

| Pl-7 | neem/eucalyptus/mahogany Azadirachta indica/Eucalyptus camaldulensis/Khaya senegalensis | 0.5669 | 56.69 | 11°07′47.10″ N, 7°38′59.21″ E |

| Pl-8 | eucalyptus Eucalyptus camaldulensis | 0.01763 | 1.763 | 11°08′25.11″ N, 7°39′08.24″ E |

| Total | 1.4324 | 143.24 | - | |

| Denotation of Plantations on the Land-Use Map in Figure 4 | Prevalent Tree Type | Surface Area | Coordinates of the Central Point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | ha | |||

| PLn-1 | black plum (Malmo) Vitex doniana | 0.01569 | 1.569 | 11°9′50.14″ N 7°37′16.65″ E |

| PLn-2 | black plum (Malmo) Vitex doniana | 0.004799 | 0.4799 | 11°9′24.22″ N 7°37′39.46″ E |

| PLn-3 | black plum (Malmo) Vitex doniana | 0.006265 | 0.6265 | 11°9′20.98″ N 7°37′45.12″ E |

| PLn-4 | mango Mangifera indica | 0.1433 | 14.33 | 11°9′31.28″ N 7°38′0.70″ E |

| PLn-5 | mahogany/black plum (Malmo) Khaya senegalensis/Vitex doniana | 0.03407 | 3.407 | 11°9′6.40″ N 7°37′59.34″ E |

| PLn-6 | mango Mangifera indica | 0.07087 | 7.087 | 11°9′8.56″ N 7°38′9.45″ E |

| PLn-7 | mahogany/date palm Khaya senegalensis/Phoenix dactylifera L. | 0.02154 | 2.154 | 11°9′39.49″ N 7°38′30.62″ E |

| PLn-8 | mango Mangifera indica | 0.003108 | 0.3108 | 11°9′0.50″ N 7°38′22.59″ E |

| PLn-9 | white teak Gmelina arborea | 0.01113 | 1.113 | 11°8′51.93″ N 7°38′13.92″ E |

| PLn-10 | mahogany/white teak Khaya senegalensis/Gmelina arborea | 0.05603 | 5.603 | 11°8′43.49″ N 7°38′31.82″ E |

| PLn-11 | mahogany/white teak Khaya senegalensis/Gmelina arborea | 0.01402 | 1.402 | 11°8′51.19″ N 7°38′35.18″ E |

| PLn-12 | guava Psidium guajava | 0.01663 | 1.663 | 11°8′37.29″ N 7°38′27.33″ E |

| PLn-13 | white teak Gmelina arborea | 0.001249 | 0.1249 | 11°8′37.12″ N 7°38′47.79″ E |

| PLn-14 | black plum (Malmo) Vitex doniana | 0.01741 | 1.741 | 11°8′33.02″ N 7°38′51.36″ E |

| PLn-15 | white teak Gmelina arborea | 0.06764 | 6.764 | 11°8′29.99″ N 7°38′45.28″ E |

| PLn-16 | mahogany/oil palm Khaya senegalensis/Elaeis guineensis | 0.04119 | 4.119 | 11°8′27.42″ N 7°38′59.06″ E |

| PLn-17 | guava/cashew Psidium guajava/Anacardium occidentale | 0.004791 | 0.4791 | 11°8′22.69″ N 7°39′4.04″ E |

| PLn-18 | guava/mango/eucalyptus Psidium guajava/Mangifera indica and | 0.02151 | 2.151 | 11°8′19.11″ N 7°39′37.35″ E |

| PLn-19 | eucalyptus Eucalyptus camaldulensis | 0.01117 | 1.117 | 11°10′4.80″ N 7°38′16.62″ E |

| PLn-20 | eucalyptus Eucalyptus camaldulensis | 0.006315 | 0.6315 | 11°10′5.70″ N 7°38′8.37″ E |

| PLn-21 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.01021 | 1.021 | 11°10′25.79″ N 7°37′52.64″ E |

| PLn-22 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.009595 | 0.9595 | 11°10′28.54″ N 7°37′48.45″ E |

| PLn-23 | mahogany Khaya senegalensis | 0.01133 | 1.133 | 11°10′26.00″ N 7°37′46.46″ E |

| Total | 0.599862 | 59.99 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurowska, E.E.; Czerniak, A.; Garba, M.L. Afforestation of Transformed Savanna and Resulting Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Zaria (Nigeria). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031160

Kurowska EE, Czerniak A, Garba ML. Afforestation of Transformed Savanna and Resulting Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Zaria (Nigeria). Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031160

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurowska, Ewa E., Andrzej Czerniak, and Muhammad Lawal Garba. 2022. "Afforestation of Transformed Savanna and Resulting Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Zaria (Nigeria)" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031160

APA StyleKurowska, E. E., Czerniak, A., & Garba, M. L. (2022). Afforestation of Transformed Savanna and Resulting Land Cover Change: A Case Study of Zaria (Nigeria). Sustainability, 14(3), 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031160