Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fundraising in the Arts

2.1.1. Managerial Initiatives to Foster Fundraising: Motivational Studies

2.1.2. Government Initiatives to Foster Fundraising: Cultural Policy

2.2. The Emerging Role of Crowdfunding

- Unlike sponsorship, private and corporate donations do not require an economic return in terms of visibility, avoiding the risk of potential commercial exploitation of the public heritage and ensuring the possibility for arts managers to better place the amount received to ensure delivery of the organization’s mission [16,66]. Indeed, the recipient cultural organization has no formal obligation to the donors, as the exploitation of cultural heritage is one of the main conditions of the enhancement of the historical–architectural heritage, with the risk of the progressive transformation of monuments into banal support for advertising [15]. Donors in crowdfunding platforms are attracted from the possibility to effectively contribute to the creative process and engage with the organizations.

- Through crowdfunding, possible democratization of the form of financing for the cultural organization encourages a participatory [65] and more democratic process in which anyone can contribute [18] and which is based on trust [30]. This practice could help organizations to overcome problems related to decreases in public financing and the inability for public administrations to effectively valorize, protect, and promote arts and cultural heritage [29].

- Potentially, crowdfunding could also leave room for innovation and experimentation while minimizing the risk of unethical practices or sponsor-seeking behavior [16,67]. The democratization also involves the cultural organizations, as it encourages bottom-up initiatives from small organizations that might not have the resources they need to start their own fundraising campaigns [47,68]. In addition, crowdfunding provides an impetus for collaboration that could speed up the financing of business projects while also requiring new sets of behaviors by the various actors. This process could result in major changes in relationships between investors and those who receive funding, creating a field where more solid participatory relationships with audiences are strengthened, as well as a sense of shared ownership of shared heritage [29,69].

An Integrated Perspective for Studying Crowdfunding in the Arts

- An open and accountable flow of communication toward potential donors [75] based on explicit requests for donations [76], preliminary specification of the activities that will benefit from donor contributions [77], complete transparency about the expenses connected with the contribution, and the results of the activities supported by the donations [78].

- Which of the three key factors for a successful fundraising campaign can be applied to a civic crowdfunding campaign in the arts sector?

- What indications does a civic crowdfunding campaign in the arts sector provide for the development and enrichment of the theory on these key factors?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context: The Art Bonus Scheme

- Area A: Maintenance, protection, and restoration of public cultural assets. Donations in this area are related to a specific asset and clearly defined projects.

- Area B: Support for public cultural institutions (e.g., museums, libraries, archives, archaeological sites and parks, monuments, concert and opera houses, and theatres, etc.), with specific references to the operational activities of performing arts institutions. This includes more generic donations in support of current operations and the ordinary activities of cultural institutions.

- Area C: Restoration and development of public theatres and auditoriums. As in Section A, the donations are related to a specific asset, but here, they are limited to public theatres and auditoriums.

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Data Collection

- A description of the results with specific reference to the three areas of intervention identified by the law.

- An analysis of the results based on the three factors identified in the literature as being important areas of interest.

- Who donates and at what level?

- Why is a donation made?

- What do the patrons finance?

4. Results

4.1. Art Bonus Results in Terms of Cultural Policy

4.2. Managerial Drivers: Donation Patterns

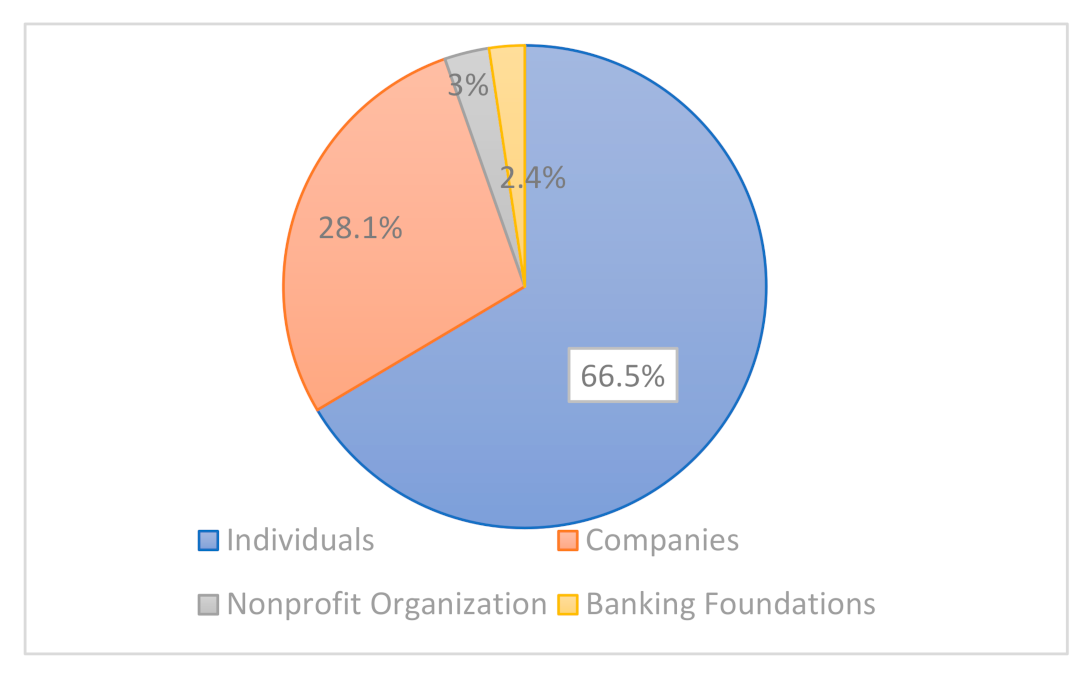

4.2.1. Who Donates and at What Level?

4.2.2. Why Is a Donation Made?

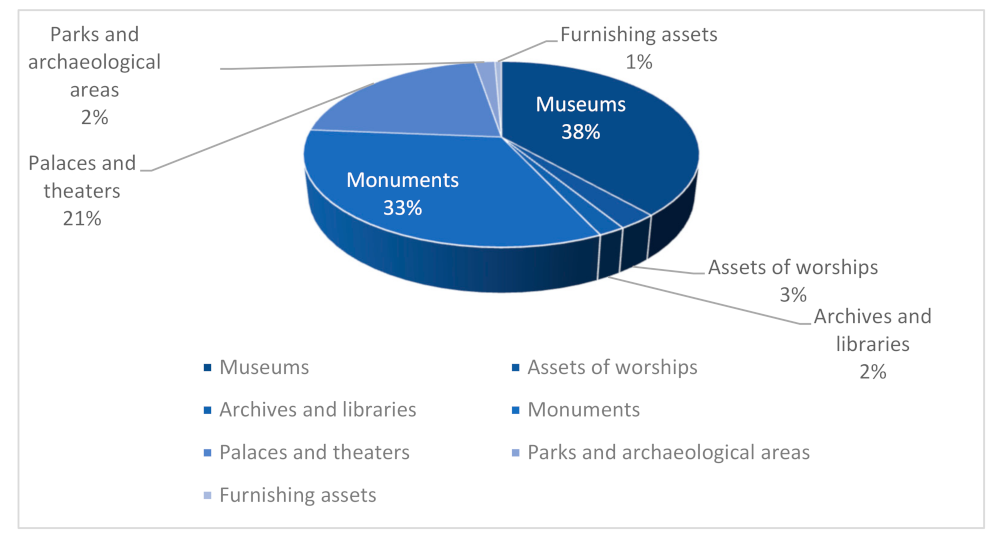

4.2.3. What Do Patrons Finance?

5. Discussion and Implications for Management

6. Conclusions

- The importance of engaging with members of the local community in which the cultural organization operates, which also increases the potential to reach a wider and international audience (this was not fully exploited in the case study discussed in this paper);

- The necessity of building a system of compensation, which can include recognition of the donations made by the donors on the website and acknowledgement of the donation that was made;

- The importance of establishing a flow of accountable communication between the organization and its donors and clearly stating how the money will be used and for what purpose.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hager, M.; Rooney, P.; Pollak, T. How fundraising is carried out in US nonprofit organisations. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2002, 7, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sargeant, A.; Shang, J. Fundraising Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrod, B.A.; Dominguez, N.D. Demand for collective goods in private nonprofit markets: Can fundraising expenditures help overcome free-rider behavior? J. Public Econ. 1986, 30, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. The Double Crisis of the Welfare State. In The Double Crisis of the Welfare State and What We Can Do about It; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Arostegui, J.A.; Villarroya, A. Patronage as a way out of crisis? The case of major cultural institutions in Spain. Cult. Trends 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruening, G. Origin and theoretical basis of new public management. Int. Public Manag. J. 2001, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Ryu, J. Crowdfunding public projects: Collaborative governance for achieving citizen co-funding of public goods. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D. Arts Management, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, F.; Ravanas, P. Marketing Culture and the Arts, 5th ed.; Carmelle and Rémi Marcoux Chair in Arts Management: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.; Kraemer, S. Fundraising as organisational knowing in practice: Evidence from the arts and higher education in the UK. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, e1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorloni, A. Designing a strategic framework to assess museum activities. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2012, 14, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural sustainability. In A Handbook of Cultural Economics; Towse, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; pp. 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T.; Boukas, N.; Christodoulou-Yerali, M. Museums and cultural sustainability: Stakeholders, forces, and cultural policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, K.A. Diversification of revenue strategies: Evolving resource dependence in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1999, 28, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolores, L.; Macchiaroli, M.; De Mare, G. Sponsorship’s Financial Sustainability for Cultural Conservation and Enhancement Strategies: An Innovative Model for Sponsees and Sponsors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, S.; Kaliampakos, D. Social transformations of cultural heritage: From benefaction to sponsoring: Evidence from mountain regions in Greece. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. A Literature Review of Empirical Studies of Philanthropy: Eight Mechanisms That Drive Charitable Giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 924–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, M.; Mion Dalle Carbonare, P.; Turrini, A. Turning crowds into patrons: Democratizing fundraising in the arts and culture. In The Routledge Companion to Arts Management; Byrnes, W.J., Brkić, A., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 409–424. ISBN 9781351030861. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, L.; Taffler, R. Does corporate philanthropy exist?: Business giving to the arts in the UK. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianecchini, M. Strategies and determinants of corporate support to the arts: Insights from the Italian context. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.; Santagata, W.; Signorello, G. Individual giving to support cultural heritage. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2011, 13, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, J.N.; Evers, U.; Lee, J.A. Personal Values and Choice of Charitable Cause: An Exploration of Donors’ Giving Behavior: Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2020, 49, 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A. Relationship fundraising: How to keep donors loyal. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2001, 12, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slyke, D.M.; Brooks, A.C. Why do people give? New evidence and strategies for nonprofit managers. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2005, 35, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bönke, T.; Massarrat-Mashhadi, N.; Sielaff, C. Charitable giving in the German welfare state: Fiscal incentives and crowding out. Public Choice 2013, 154, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caldwell, M.; Woodside, A.G. The Role of Cultural Capital in Performing Arts Patronage. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2003, 5, 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hemels, S.; Goto, K. (Eds.) Tax Incentives for the Creative Industries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, J.M. Tax Incentives in Cultural Policy. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1253–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Marchegiani, L. From Mecenatism to crowdfunding: Engagement and identification in cultural-creative projects. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Kim, D.K. Why do investors participate in tourism incentive crowdfunding? The effects of attribution and trust on willingness to fund. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bœuf, B.; Darveau, J.; Legoux, R. Financing creativity: Crowdfunding as a new approach for theatre projects. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2014, 16, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, S.T. Crowdfunding and Diaspora Philanthropy: An Integration of the Literature and Major Concepts. Voluntas 2017, 28, 492–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehle, N.; Otte, P.P.; Drozdova, N. Crowdfunding Sustainability. In Advances in Crowdfunding; Shneor, R., Zhao, L., Flåten, B.-T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 393–422. [Google Scholar]

- Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Natalicchio, A.; Panniello, U.; Roma, P. Understanding the crowdfunding phenomenon and its implications for sustainability. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 141, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiver, A.; Barroca, L.; Minocha, S.; Richards, M.; Roberts, D. Civic crowdfunding research: Challenges, opportunities, and future agenda. New Media Soc. 2015, 17, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research and application. Design and methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. Three provocations for civic crowdfunding. Inform. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, S.; Tappin, E. Strategy in the public sector: Management in the wilderness. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 955–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre Blundo, D.; García Muiña, F.E.; Fernández del Hoyo, A.P.; Riccardi, M.P.; Maramotti Politi, A.L. Sponsorship and patronage and beyond: PPP as an innovative practice in the management of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.; Cassalia, G.; Spina, L. Della New models of Public-private Partnership in Cultural Heritage Sector: Sponsorships between Models and Traps. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, D.; Slack, R. Corporate “philanthropy strategy” and “strategic philanthropy” some insights from voluntary disclosures in annual reports. Bus. Soc. 2008, 47, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.; Joulfaian, D. Taxes and corporate giving to charity. Public Financ. Rev. 2005, 33, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Garbarino, E. Customers of Performing Arts Organisations: Are Subscribers Different from Nonsubscribers? Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2001, 6, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Koutiva, E. Financial Giving of Foundations and Businesses to Environmental NGOs: The Role of Grantee’s Legitimacy. Voluntas 2014, 25, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, N.D.; Roehrich, J.K.; George, G. Social Value Creation and Relational Coordination in Public-Private Collaborations. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 906–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Ortmann, A. Do Donors Care About the Price of Giving? A Review of the Evidence, with Some Theory to Organise It. Voluntas 2016, 27, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. Crowdfunding and the Role of Managers in Ensuring the Sustainability of Crowdfunding Platforms; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 9789279377273. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, K.V. Cultural Patronage in Comparative Perspective: Public Support for the Arts in France, Germany, Norway, and Canada. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 1998, 27, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwi, D. Public support of the arts: Three arguments examined. J. Cult. Econ. 1980, 4, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.E. Fundraising in the USA and the United Kingdom: Comparing today with directions for tomorrow. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 1997, 2, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valančienė, L.; Jegelevičiūtė, S. Crowdfunding for creating value: Stakeholder approach. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beldad, A.; Gosselt, J.; Hegner, S.; Leushuis, R. Generous But Not Morally Obliged? Determinants of Dutch and American Donors’ Repeat Donation Intention (REPDON). Voluntas 2015, 26, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, F.G. The future of the Welfare State. Crisis Myths and Crisis Realities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, K.V. Entrepreneurship or cultural Darwinism? Privatization and American cultural patronage. J. Arts Manag. Law, Soc. 2003, 33, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Dale, H.; Chisolm, L. The Federal Tax Treatment of Charitable Organizations. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook; Powell, W.W., Steinberg, R., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 267–306. [Google Scholar]

- Dehne, A.; Friedrich, P.; Nam, C.W.; Parsche, R. Taxation of nonprofit associations in an international comparison. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2008, 37, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepking, P.; Handy, F. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-137-55584-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Zhao, J.L.; Hassna, G. Government-incentivized crowdfunding for one-belt, one-road enterprises: Design and research issues. Financ. Innov. 2016, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, Y.; Hwang, J. Crowdfunding as an Alternative Means for Funding Sustainable Appropriate Technology: Acceptance Determinants of Backers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dollani, A.; Lerario, A.; Maiellaro, N. Sustaining cultural and natural heritage in Albania. Sustainability 2016, 8, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morduch, J. The microfinance promise. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1569–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poetz, M.K.; Schreier, M. The value of crowdsourcing: Can users really compete with professionals in generating new product ideas? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drucker, P.F. The new pluralism. Lead. Lead. 1999, 1999, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokka, S.; Badia, F.; Kangas, A.; Donato, F. Governance of cultural heritage: Towards participatory approaches. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2021, 11, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill, J.R.; Harrington, J.R. Revenue Sources and Social Media Engagement Among Environmentally Focused Nonprofits. J. Public Nonprofit Aff. 2017, 3, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQuillin, I.; Sargeant, A. Fundraising Ethics: A Rights-Balancing Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chirisa, I.; Mukarwi, L.; Rajab Mutamanda, A. Prospects and Options for Sustainable and Inclusive Crowdfunding in African Cities. In Crowdfunding and Sustainable Urban Development in Emerging Economies; Benna, U.G., Benna, A.U., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kappel, T. Ex ante crowdfunding and the recording industry: A model for the U.S. Loyola of Los Angeles. Entertain. Law Rev. 2009, 29, 375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Y.; Okuyama, N. Local Charitable Giving and Civil Society Organizations in Japan. Voluntas 2015, 26, 1164–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, I. Effective Fundraising for Nonprofits: Real-World Strategies That Work; Nolo: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1413322999. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, S.R.; Davis, J.C. Arts Patronage: A Social Identity Perspective. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2006, 14, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins Johnson, J.; Ellis, B. The influence of messages and benefits on donors’ attributed motivations: Findings of a study with 14 American performing arts presenters. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2011, 13, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.R. The Prospective Role of Economic Stakeholders in the Governance of Nonprofit Organizations. Voluntas 2011, 22, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C.J.; Baskerville, R.F. Charity Transgressions, Trust and Accountability. Voluntas 2011, 22, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayr, M.; Handy, F. Charitable Giving: What Influences Donors’ Choice Among Different Causes? Voluntas 2019, 30, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.R.; Quynn, K.L. Planned Giving: A Guide to Fundraising and Philanthropy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 0470480823. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, A.; Hudson, J.; Wilson, S. Donor Complaints About Fundraising: What Are They and Why Should We Care? Voluntas 2012, 23, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Selasinsky, C.; Lutz, E. The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvilichovsky, D.; Inbar, Y.; Barzilay, O. Playing both sides of the market: Success and reciprocity on crowdfunding platforms. SSRN Res. Pap. 2015, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scapens, R.W. Doing Case Study Research. In The Real Life Guide to Accounting Research. A Behind-the-Scenes View of Using Qualitative Research Methods; Humphrey, C., Lee, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from "Case Study Research in Education"; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; ISBN 0787910090. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO-UIS 2009 UNESCO Framework For Cultural Statistics; UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009; ISBN 9789291890750.

- Associazione Civita Donare si può? Gli italiani e il mecenatismo culturale diffuso; Associazione Civita: Milano, Italy, 2009.

- European Union (EU); Institute for International Relations (IMO). Encouraging Private Investment in the Cultural Sector; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; de Mille, A. Fundraising for Museums. AIM Focus Pap. 2006, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://silo.tips/download/fundraising-for-museums (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Ranganathan, S.K.; Henley, W.H. Determinants of charitable donation intentions: A structural equation model. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2008, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelli, C.C.; Rentschler, R.; Fanelli, S. Value co-creation in non-profit organisations: The evolution of philanthropic strategies as entrepreneurial activities. In Proceedings of the EURAM 2018 (European Academy of Management) Conference, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 19–22 June 2018. Conference proceedings 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, S.; Donelli, C.C.; Zangrandi, A.; Mozzoni, I. Balancing artistic and financial performance: Is collaborative governance the answer? Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. Corporate philanthropy in France, Germany and the UK: International comparisons of commercial orientation towards company giving in European nations. Int. Mark. Rev. 1998, 15, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. Generosity vs. altruism: Philanthropy and charity in the United States and United Kingdom. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2001, 12, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years 2007–2008 | Years 2014–2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | |

| Cultural Heritage | 1375 | 24,475,272 | 1788 | 62,303,715 |

| Performing Arts Institutions | 547 | 38,928,713 | 1361 | 60,975,373 |

| Total | 1922 | 63,403,985 | 3149 | 123,279,088 |

| Cultural Heritage Institutions | Performing Arts Institutions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | Average Donation (€) | No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | Average Donation (€) | |

| Individuals | 1227 | 3,148,747 | 2566 | 866 | 3,458,764 | 3994 |

| Corporates | 661 | 59,154,968 | 89,493 | 495 | 57,498,610 | 116,159 |

| Total | 1788 | 62,303,715 | 34,845 | 1361 | 60,957,373 | 44,789 |

| Area A + Area C | Area B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| € | % | € | % | |

| Individuals | 6,241,894 | 10% | 3,458,764 | 5.7% |

| Companies | 27,191,016 | 42% | 32,796,508 | 53.8% |

| Nonprofit organizations | 1,387,698 | 2% | 17,671,004 | 29.0% |

| Banking foundations | 30,576,254 | 47% | 7,031,097 | 11.5% |

| Total | 65,396,862 | 100% | 60,957,373 | 100% |

| Areas A+ Area C | Area B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | Average Donation (€) | No. of Donations | Amount Donated (€) | Average Donation (€) | |

| Individuals | 1227 | 3,148,747 | 2566 | 866 | 3,458,764 | 3994 |

| Companies | 463 | 27,191,016 | 58,728 | 424 | 32,796,508 | 77,350 |

| Nonprofit organizations | 61 | 1,387,698 | 22,749 | 33 | 17,671,004 | 535,485 |

| Banking foundations | 37 | 30,576,254 | 826,385 | 38 | 7,031,097 | 185,029 |

| Total | 1788 | 62,303,715 | 34,845 | 1361 | 60,957,373 | 44,789 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donelli, C.C.; Mozzoni, I.; Badia, F.; Fanelli, S. Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031641

Donelli CC, Mozzoni I, Badia F, Fanelli S. Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031641

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonelli, Chiara Carolina, Isabella Mozzoni, Francesco Badia, and Simone Fanelli. 2022. "Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031641

APA StyleDonelli, C. C., Mozzoni, I., Badia, F., & Fanelli, S. (2022). Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy. Sustainability, 14(3), 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031641