Transport Accessibility and Tourism Development Prospects of Indigenous Communities of Siberia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- identification of regional contexts in interrelations for development of transport systems and tourism in the studied territories (natural, socioeconomic, ethnocultural, institutional factors);

- analysis of impact of the development of transport networks and the tourism industry on local communities;

- model characteristics of indigenous communities’ attitude to tourism and transport development in the territories of their residence.

2. Related Works

3. Methods

4. Study Area

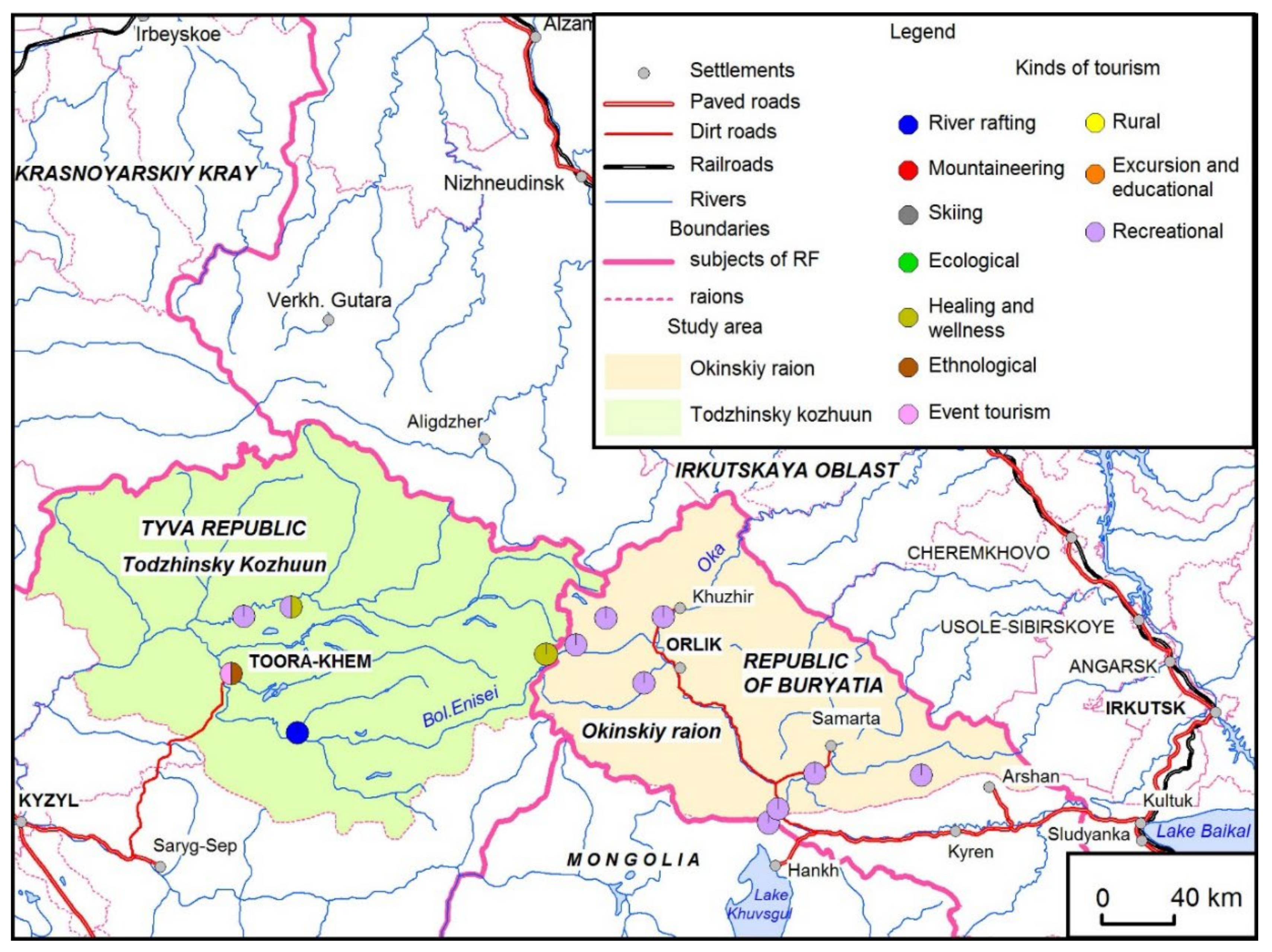

4.1. Case 1. Todzhinsky Kozhuun, Republic of Tyva

4.2. Case 2. Okinsky District, Republic of Buryatia

Transport Systems of Todzhinsky Kozhuun and the Okinsky District

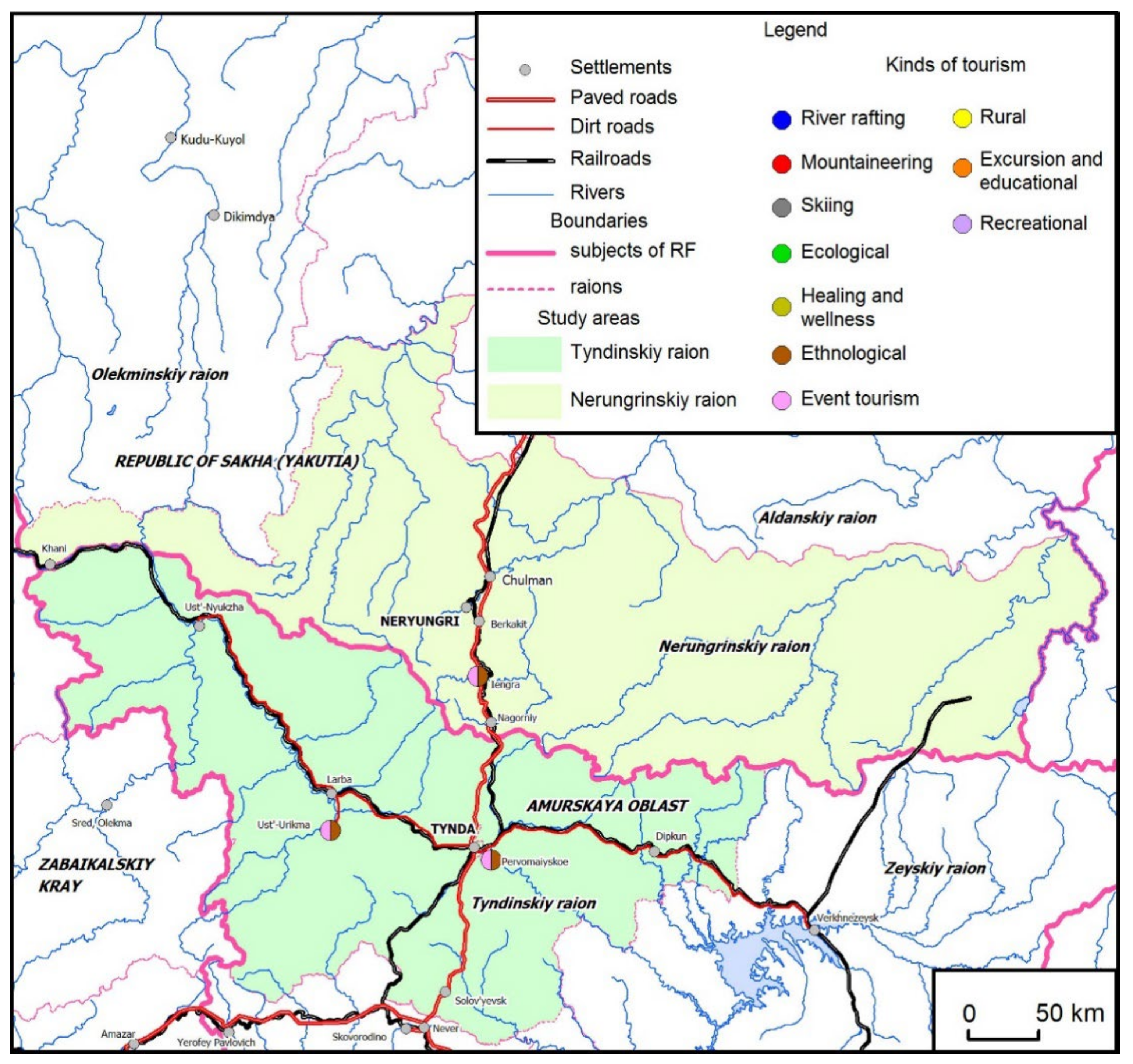

4.3. Case 3. Tyndinsky District, Amur Region

4.4. Case 4. Neryungri District, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

Transport System of Tynda and Neryungri Districts

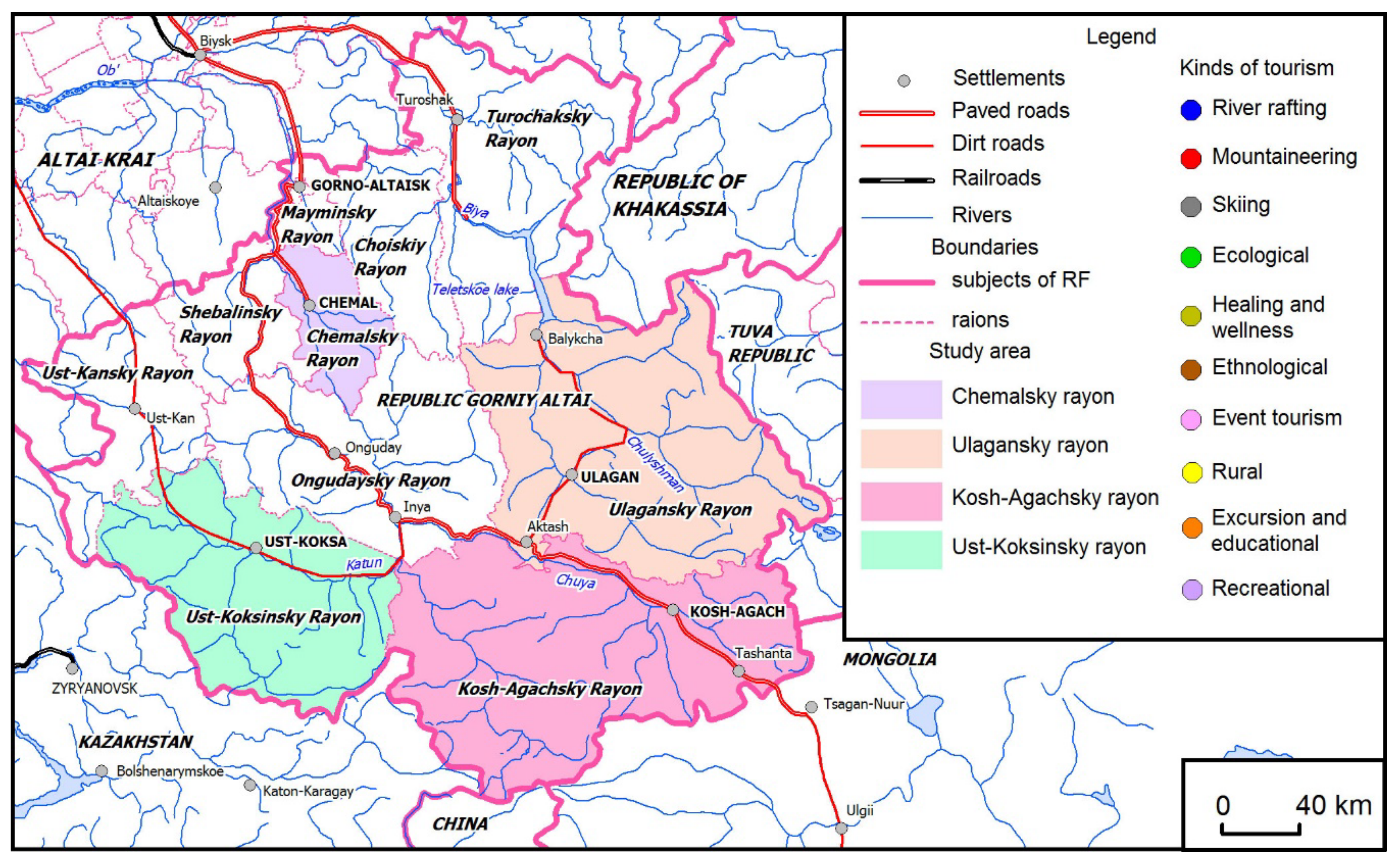

4.5. Case 5. Republic of Altai

4.6. Transport System of the Altai Republic

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Inter-Development of Transportation Networks and Tourism Industry in the Study Areas

5.1.1. Tourism Development in the Todzhinsky Kozhuun and Okinsky Districts

- health-improvement: (therapeutic and healing spring (arzhaans) “Choigan” (Izig-Sug), Olbuk, Nogaan-Khol, and Myima-Khash.

- event tourism: (Festival of reindeer breeders of Todzha kozhuun, National holiday “NAADYM”, International Day of the Indigenous Minorities of the North, Siberia and the Far East, Republican competition with Todzha sketches “Tozhuayannary”);

- business: business meetings with representatives of the government and the Ministry of the Republic of Tyva;

- cultural and educational tourism: ecological routes “by the path of reindeer people” through picturesque places of kozhuun on the territory of the “Azas” reserve, the place of Kyzyl-Dash for children and adults.

- recreational tourism: Lake Azas, Lake Dorug-Khol, and Lake Albuk.

5.1.2. Tyndinsky District

5.1.3. Neryungri District

- low availability of credit resources with insufficient start-up capital and a weak level of knowledge for a successful start of entrepreneurial activity in the field of tourism;

- high cost of borrowed funds attracted by small- and medium-sized businesses to perform economic activities;

- low share of enterprises in the manufacturing sector, predominance of the trade sector, and low demand for the service sector;

- shortage of qualified personnel and insufficient levels of professional training;

- low entrepreneurial activity of young people.

5.1.4. Altai Republic

5.2. Models of Attitudes among Representatives of Indigenous Small People (Communities) towards Transportation and Tourism Development in the Territories

5.2.1. “The Road of Life” (The Organizing Role of Main Transport Arteries)

5.2.2. “Escape Route” (Role of New Roads in the Desolation of Rural Areas)

5.2.3. “Bear’s Corner, but Mine” (Unwillingness to Open Their Territories to Mass Tourism)

5.2.4. “Off-Road Is My Bread” (How the Local Population Makes Money Off-Road)

5.2.5. “Waiting for a Miracle” (Hopes for Improvements Related to Road Development Prospects)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ru/about/development-agenda/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future URL. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Pirogova, O.V.; Pirogova, A.Y. The role of sustainable tourism in the world. Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Res. 2017, 7, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives. International Development Research Center and the United Nations Environment Program: Local Agenda: Planning Guide, XXI. Toronto. 1996, p. 178. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rietveld, P.; Nijkamp, P. Transport and regional development. 1992, p. 22. Available online: https://degree.ubvu.vu.nl/repec/vua/wpaper/pdf/19920050.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Baird, B.A. Public Infrastructure and Economic Productivity: A Transportation-Focused Review. Transp. Res. Rec. 2005, 1932, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrukov, L.A. The Continental-Oceanic Dichotomy in International and Regional Development. Novosibirsk. 2008, p. 369. Available online: https://earthpapers.net/kontinentalno-okeanicheskaya-dihotomiya-v-mezhdunarodnom-i-regionalnom-razvitii (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Semina, I.A. Regional transport systems: Typology and vectors of development. In Multi-Vector Approach in the Development of Russian Regions: Resources, Strategies and New Trends; Streletsky, V.N., Ed.; IP Matushkina I.I.: Moscow, Russia, 2017; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, K.; Zhao, J. Analysis of the Relationships between Tourism Efficiency and Transport Accessibility—A Case Study in Hubei Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Knox, H. The enchantments of infrastructure. Mobilities 2012, 7, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroeva, G.N.; Slobodchikova, D.V. Ensuring transport accessibility of the population as an important direction of the socio-economic development of the region. Sci. Notes PNU 2016, 7, 673–679. Available online: https://ejournal.pnu.edu.ru/media/ejournal/articles-2016/TGU_7_280.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Transport strategy of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2030. Available online: http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_82617/12dbe84ab7402c41a061dee3399c090bf6932cc3/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Harvey, P. The topological quality of infrastructural relation: An ethnographic approach. Theory Cult. Soc. 2012, 29, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakoglou, D. The road from capitalism to capitalism: Infrastructures of (post) socialism in Albania. Mobilities 2012, 7, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuklina, V.V. Transport (in) accessibility: Experience and practices of mobility of residents of settlements in the national republics of Siberia. The Collection of Scientific Papers Based on the Results of the All-Russian Scientific and Practical Seminar: Republics in the East of Russia: Trajectories of Economic, Demographic and Territorial Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329711076_TRANSPORTATION_INACCESSIBILITY_EXPERIENCE_AND_PRACTICES_OF_MOBILITIES_IN_THE_SETTLEMENTS_OF_THE_NATIONAL_REPUBLICS_OF_SIBERIA (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Argounova-Low, T. Roads and Roadlessness: Driving trucks in Siberia. J. Ethnol. Folk. 2012, 6, 71–88. Available online: https://aura.abdn.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2164/12273/RoadsandRoadlessness.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Kuklina, V.V.; Osipova, M.E. The role of winter roads in ensuring transport accessibility of the Arctic and subarctic regions of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Soc. Environ. Dev. 2018, 2, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilyasov, A.N.; Zamyatina, N.; Goncharov, R.V. There is no creativity without mobility: Anthropology of transport in Siberia and the Far East. Spat. Econ. 2019, 15, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshalova, A.S.; Novoselov, A.S. Competitiveness and development strategy of municipalities. Reg. Econ. Sociol. 2010, 3, 219–236. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46525363_Competitiveness_and_development_strategies_for_municipal_units/link/5e4cf94f458515072da8b53a/download (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Schweitzer, P.; Povoroznyuk, O.; Schiesser, S. Beyond wilderness: Towards an anthropology of infrastructure and the built environment in the Russian North. Polar J. 2017, 7, 58–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozanenko, A.A. Spatial isolation and sustainability of local communities: Towards the development of existing approaches. Bull. Tomsk. State Univ. Philosophy Sociol. Political Sci. 2017, 40, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, Y. Roadlessness and the Person: Mode of Travel in the Reindeer Herding Part of the Kola Peninsula. Acta Boreal. 2009, 1, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirin, D.A.; Madry, C. Transformation processes in traditional nature management systems in the Altai mountain region. In Proceedings of the 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference, Vienna, Austria, 27–29 November 2017; Volume 17, pp. 1015–1024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322930747_TRANSFORMATION_PROCESSES_IN_TRADITIONAL_NATURE_MANAGEMENT_SYSTEMS_IN_THE_ALTAI_MOUNTAIN_REGION (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Dirin, D.; Madry, C. Formation and development factors of Altai ethno-cultural landscapes. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 26–27 September 2018; Volume 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groshev, I.L.; Grosheva, I.A.; Grosheva, L.I. Regional Imbalances in the Socio-Economic Development of Russia. Indigenous Peoples: History, Traditions and Modernity; Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2019; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ryashchenko, S.V. Regional disparities in the qualitative characteristics of the population of Asian Russia. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2011, 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, L.G. Tourism as a resource for territory development. Successes Mod. Nat. Sci. 2007, 12, 90–92. Available online: https://natural-sciences.ru/ru/article/view?id=11994 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Bilichenko, I.N.; Kobylkin, D.V.; Kuklina, V.V.; Bogdanov, V.N. Development of the Informal Road Network and its Impact on the Transformation of Taiga Geosystems. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2021, 42, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: A developing global approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09669589309450696] (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sundari, R.; Michael Hall, K.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, pp. 1–21. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09669582.2020.1775621 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Sustainable Development of Tourism. Sustainable Development of Tourism—World Tourism Organization—Definition. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Budeanu, A. Impacts and responsibilities for sustainable tourism: A tour operator’s perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponedelko, G.N. Sustainable Tourism as a Factor in the Regional Development of EU Countries. Regional Economy and Management: Electronic Scientific Journal. Available online: https://eee-region.ru/article/6401/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on antidam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davaa, E.K. Modern sociocultural situation of Tuvinas-Tojins. In Proceedings of the IV International Scientific and Practical Conference Social and Economic Aspects of Education in Modern Society, Warsaw, Poland, 18–19 July 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335687834_Proceedings_of_the_IV_International_Scientific_and_Practical_Conference_Social_and_Economic_Aspects_of_Education_in_Modern_Society/link/5d754297a6fdcc9961ba4b21/download (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Dirin, D.A.; Fryer, P. The Sayan borderlands: Tuva’s ethnocultural landscapes in changing natural and sociocultural environments. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 13, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Popular Front in Tuva Asks the Authorities to Come Up with an Initiative to Change the Legislation on Territories of Traditional Land Use. Available online: https://onf.ru/2021/10/04/narodnyy-front-v-tuve-prosit-vlasti-vyyti-s-iniciativoy-ob-izmenenii-zakonodatelstva-o/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kuklina, V.; Dashpilov, T. Constructing a map of transport communication “Sayan crossroads”. Tartaria Magna. 2013, 2, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Imetkhenov, A.B. Atlas of the Republic of Buryatia; Federal Service of Geodesy and Cartography of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2000; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Rassadin, I.V. Comparative analysis of animal husbandry of Soyots and Buryats. Humanit. Vector 2017, 12, 190–195. Available online: http://zabvektor.com/wp-content/uploads/080219030207-rassadin.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kurdyukov, V.N. Traditional Soyot Economy and Its Dynamics. Bull. Irkutsk. State Univ. 2012, 1, 176–185. Available online: https://izvestiageo.isu.ru/en/article/file?id=5 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Gulgenova, S.Z. The history of the development of traditional nature management in the Oka Mountains (Eastern Sayan). Bull. Buryat State Univ. 2009, 4, 24–26. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/istoriya-razvitiya-traditsionnogo-prirodopolzovaniya-v-gornoy-oke-vostochnyy-sayan (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Dabiev, D.F.; Dabiev, U.M. Socio-Economic characteristic of the Toja district of Tuva. Int. J. Appl. Fundam. Res. 2015, 9, 520–522. Available online: https://s.applied-research.ru/pdf/2015/9-3/7364.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Rassadin, I.V.; Mitkinov, M.K. The study of the material and spiritual culture of the Tofalars: History, modernity, prospects. Bull. Tyumen State Univ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 1, 203–217. Available online: https://vestnik.utmn.ru/upload/iblock/c67/203_217.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Donahoe, B. Who Owns the Taiga? Inclusive vs. Exclusive Senses of Property among the Toju and Tofa of Southern Siberia. Sibirica 2006, 5, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todzhinsky Kozhuun. Official Portal of the Republic of Tyva. Available online: https://rtyva.ru/region/msu/777/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- A Mining and Processing Plant for the Production of Copper, Lead and Zinc Concentrates Is Preparing to Launch in the Tuva Republic. Available online: https://rtyva.ru/press_center/news/building/14651/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Chinese “Longxing” Launched a Polymetallic Mining and Processing Plant in Tuva. Available online: https://ria.ru (accessed on 30 March 2018).

- Airlines “Tuva Avia”: Official Website. Available online: http://avia-tuva.ru (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Sambyalova, Z.N. The History of the Origin of the Orlik Village. Available online: http://okagazeta.ru/articles/media/2014/7/21/istoriya-zarozhdeniya-sela-orlik/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Golden Mountains of Altai (Russian Federation). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/ru/list/768 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Rudenko, S.I. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen; Thompson, M.W., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1970; Available online: https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/ehrafa/citation.do?method=citation&forward=browseAuthorsFullContext&id=rl60-002 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Slon, V. The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature 2018, 561, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, M. The evolutionary history of Neanderthal and Denisovan Y chromosomes. Science 2020, 369, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polosmak, N.V. The burial of a noble Pazyryk woman. Bull. Anc. Hist. 1996, 4, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourist passport of the Municipality “Todzhinsky kozhuun of the Tyva Republic”. 2020. Available online: http://todzhinsky.ru/page.php?copylenco=omsu&id_omsu=17/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kalikhman, A.D.; Kalikhman, T.P. Design of the Transboundary Ethno-Natural Protected Area “Sayan Crossroads”; Publishing House of Irkutsk State Technical Universit: Irkutsk, Russia, 2009; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Rossikhin, A.I. The current state and prospects of tourism development in the East Sayan tourist and recreational mountain territory. In Proceedings of the I International Scientific and Practical Conference, Gorno-Altaisk, Russia, 26–27 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shpeizer, G.M.; Makarov, A.A.; Rodionova, V.A.; Mineeva, L.A. Shumak’s mineral waters. Izvestiya Irkutskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta 2012, 5, 293–309. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/shumakskie-mineralnye-vody (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Official Website of the Tyndinsky District. Available online: http://atr.tynda.ru/ (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Bus Excursions in Tynda. Available online: https://nashatynda.ru/news/category/dosug/avtobusnye-ekskursii-po-tynde (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Holy Spring. Available online: http://svyato.info/amurskaja-oblast/tyndinskijj-rajjon-amurskaja-oblast/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Day of a Reindeer Breeder and a Hunter in Ust-Urkima. Available online: https://visitamur.ru/tour/den-olenevoda-i-okhotnika-v-ust-urkime/#scroll (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Rudoi, A.N.; Lysenkova, Z.V.; Rudsky, V.V.; Shishin, M.Y.; Lysenkova, Z.V.; Rudsky, V.V. Ukok (Past, Present, Future); Publishing house of the Altai State University: Barnaul, Russia, 2000; p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Conceição, S. Indigenous Tourism Critical to Sustainable Future of Travel. Adventure Travel Trade Association. Available online: https://www.adventuretravelnews.com/indigenous-tourism-critical-to-sustainable-future-of-travel (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Kuklina, M.; Trufanov, A.; Krasnoshtanova, N.; Urazova, N.; Kobylkin, D.; Bogatyreva, M. Prospects for the Development of Sustainable Tourism in the OkinskyDistrict of the Republic of Buryatia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Research on Tourism, Indigenous Peoples and Economic Development: A Missing Component. Land 2021, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Community | Number of Interviewees | Local/Indigenous Residents (LR) | Government Officials (GO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toora-Khem | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Orlik | 15 | 13 | 2 |

| Pervomaisky | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Iengra | 12 | 9 | 3 |

| Ust-Urkima | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Elekmonar | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Edigan | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Kurai | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Beltir | 4 | 4 | - |

| Balyktuul | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Multa | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Karagay | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Study Areas | The Area of the Land | District Center | Distance from the District Center to the Administrative Center of the Region, Republic | Population of the District | Ethnic Composition of Districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todzhinsky kozhuun | 44.8 thousand km2 | Toora-Khem village | 230 km to Kyzyl | 6649 | Tojins: 44.7% Tuvans: 33.6% Russians: 19.8% |

| Okinsky district | 26.6 thousand km² | Orlik village | 700 km to Ulan-Ude | 5452 | Soyoty: 59.9% Buryats: 33.3% Others: 6.8% |

| Tyndinsky district | 83.3 thousand km² | Tynda town | 824 km to Blagoveshchensk | 13,013 | Russians: 81.2% Koreans: 2.7% Tatars: 1.1% Ukrainians: 0.4% Evenki: 0.4%. |

| Neryungri district | 98.8 thousand km² | Neryungri town | 808 km to Yakutsk | 74,900 | Russians: 78% Ukrainians: 6.2% Evenki: 1.4% Others: 14.4% |

| Altai Republic | 92,6 thousand km² | Gorno-Altaysk town | Distance from Gorno-Altaysk to regional centers from 10 km (Maima) to 460 km (Kosh-Agach) | 220,954 | Russians: 56.6% Altaians: 33.9% Kazakhs: 6.2% Others: 3.3% |

| Key Settlements | Population | Representatives of Indigenous Minorities | Traditional Branches of the Economy | Transport Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toora-Hem village | 2387 | Tuvan-Tojin | Reindeer husbandry | Automobile dirt road through the ferry, a bridge is being built |

| Orlik village | 2555 | Soyots | Reindeer breeding and yak breeding | Automobile dirt road |

| Ust-Urkima village | 260 | Evenki | Hunting and fishing, reindeer husbandry | Highway, 28 km to the south, Larba station on the BAM. |

| Iyengra village | 917 | Evenki | Hunting and fishing, reindeer husbandry | Federal highway A360 (formerly M56) “Lena” |

| Elekmonar village | 1895 | Altai-kizhi | Driving cattle breeding (sheep breeding, horse breeding, cattle breeding), hunting | The road with a solid Automobile cover “Chemalsky tract” |

| Edigan village | 246 | Altai-kizhi | Driving cattle breeding (sheep breeding, horse breeding, cattle breeding), hunting | Automobile dirt road |

| Kurai village | 427 | Altai-kizhi | Driving cattle breeding (sheep breeding, horse breeding, goat breeding), hunting | Federal highway P256 (formerly M52) “Chuysky tract” |

| Beltir village | Permanent population: 77 people Seasonal: up to 250 people | Telengites | Driving cattle breeding (sheep breeding, horse breeding, goat breeding), hunting | Automobile dirt road |

| Balyktul village | 1340 | Telengites | Driving cattle breeding (sheep breeding, horse breeding, goat breeding), hunting | Automobile road with a hard surface “Ulagansky tract” |

| Multa village | 704 | Russian Old Believers | Agriculture (cultivation of grain and cereal crops), truck farming, cattle breeding, horse breeding, maral breeding, beekeeping, hunting, fishing, gathering wild plants | Uimonsky tract hard-surfaced automobile road |

| Karagay village | 446 | Russian Old Believers | Maral breeding, horse breeding, cattle breeding, beekeeping, horticulture, hunting, fishing | Soil-gravel road |

| + Positive Attitudes | − Negative Attitudes |

|---|---|

| “Some take tourists from Orlik to the pass, they also earn money, that is, they provide the Ural truck-, at the pass there are already men with horses, they immediately offer services 1 horse 2.5 thousand (rubles-author) there and back, there you have to go on horseback across the pass…” [Woman, local resident, 46 years old, Orlik] | “Well, they (the tourists-the author) would just drive along the Chuisky tract. Well, on an excursion with a knowledgeable person who will not allow nature to ruin… So in fact everywhere they themselves will crawl in their jeeps. All the pastures were plowed up, all the animals were scared away.” [Male, 54 years old, local resident, p. Elekmonar] |

| “Foreigners came before the Covid restrictions: Chinese, Turks, from Lithuania. Scientists from Tajikistan, other countries, Vladivostok, and Khabarovsk also came. Tourists are taken away/brought by tablet operators (UAZ car-auth.)… Some take tourists to the upper reaches of the Yenisei, there is a waterfall, they just take a look… The number of guests is not decreasing, they are constantly populated. Business travelers come here to work. When the pandemic was, there were no tourists and business travelers, they rarely came here. … There were a lot of tourists in front of the covid, they came from other regions. … When the bridge is built, people will come here more often [Woman, 74 years old, hostess of the hotel, c. Toora-Khem]. | “I understand, of course, on the territory of the Russian Federation, please, but I want the Okinsko-Tunki park to be made and to be prohibited from sailing along the rivers with their windmills. So that tourists come just to see. They act in a barbaric way. Sometimes fish are taken out in whole barrels. And we don’t know, maybe they hunt, after all, we cannot check everyone, according to the law it is not allowed. There used to be a border zone, until the 1990s, there was a strict regime here and they did not have the right to travel. Tunkinsky, Okinsky, Zakamensky districts-all border areas, if they restored it, I would be very pleased” [Woman, 65 years old, medical worker, p. Orlik). |

| “The Evenk village is like an ethnographic complex where events, festivals are held, masters and craftswomen gather, and competitions in northern all-around events are held. We usually spend the Reindeer Herder’s Day at the Central Estate. That year the collective came to perform with us, I just want Evenk … … They (the masters of traditional crafts-author) do everything, sell, maybe the sales are not going as we would like, but their products are good, they communicate with each other. Yes, they conduct master classes … [Woman, administration representative, 42 years old, Pervomaisky] | “They actually tried to motivate people to do this, but we have the specificity of animal husbandry, it is like this, every month there is scheduled in its own way: who, what, when they do … His main source of income is animal husbandry, which he has known from time immemorial. He knows: I’ll raise this calf and in a year and a half he will give me 150 kg of meat. So, here you also need to step over this one. There is no time to provide services there or has never provided, and now provide? To clean up, wash someone else’s bed, wash the baths are the same, well, this one, purely mental” [Male, 49 years old, administration representative, p. Orlik] |

| “We have a lot of tourists. I do not know if the tourists take out fish, I think not. They ride more for the soul. I have friends who take these tourists. But this is exactly about tourists, and there are poachers” (Woman, 35 years old, local resident, Toora-Khem village) | “When tourists leave garbage and behave this way, of course, I have a negative attitude. In Viber they write that they waste a lot. But I don’t go there, I know that this is happening there” (Woman, 60 years old, medical worker, Orlik village). |

| “Tourists with backpacks are a special kind of people. Usually very respectful, intelligent. And they do not stay with us. They will come-backpacks on their shoulders and in the mountains” [Man, 37 years old, local resident, p. Multa]. | “What is good about mass tourism? People with big money come and behave like the owners of this land and all life. What entertainment they have on vacation-drunkenness and lewdness. Young people are already morally dissipated, and with such tourism they will finally become corrupted” [Woman, 54 years old, local resident, p. Upper Uimon] |

| “Of course, here now only on marals (Altai subspecies of red deer, whose young antlers are used in pharmaceuticals—author), but you can make money on tourists. My brother and I, for example, offer a transfer in our UAZ vehicles. Basically we will take you to the Lower Multinskoye Lake. For one rise 5000 rubles. And in the leshoz my salary is 20,000 rubles. So consider that it is more profitable if there are people who want to eat every day in the summer. And sometimes twice a day” [Male, 37 years old, local resident, p. Multa]. | “If they build this road, everyone will be trampled here. There will be no stone unturned from our beauty… And there will be a road, they will immediately start buying land and building hotels. There will be no room for us here” [Man, 37 years old, local resident, p. Multa]. |

| “Many people want to visit the Chulyshman valley and drive to the southern shore of Lake Teletskoye, but they are afraid. Because the road is very bad, the pass is dangerous. If they make a good road, everyone will be fine!” [Male, 48 years old, owner of a camp site, p. Balyktuyul]. | “If Chinese tourists come, we won’t get anything from them. Is that rubbish. They will be served by Chinese firms. It’s the same all over the world” [Woman, 58 years old, hostess of the guest house, p. Elekmonar]. |

| + Positive Attitudes | − Negative Attitudes |

|---|---|

| “The pluses are, of course: the preservation of nature, everyday life, and customs. It is most important” [Male, administration worker, 40 years old, Toora-Khem]. | “The disadvantages, one can immediately see, in connection with the remoteness—backwardness. We have no new buildings here, have you noticed? If in Kyzyl, for example, it is possible to build a school or a kindergarten for 100 million, we get 130–140, and the question is: where to get these percentages? Therefore, we receive a refusal…” [Male, administration worker, 40 years old, Toora-Khem]. |

| “The Chuisky tract is the road of life for us! All would have left long ago if he had not been there. I myself moved here from Yazula to be closer to civilization. Here, if necessary, you can quickly get to the hospital in Kosh-Agach or call an ambulance-he will come. They bring everything to the shops. And there is none of this. Only the old people were left alone. So my parents stayed there-they don’t want to move. Otherwise, I probably would have left for the City. … A lot of tourists pass by in the summer. People are constantly passing by our house. Sometimes they ask for directions. They go here to Aktru, to the glaciers. My husband and I are thinking of building a guest house in our yard ”[Woman, 36 years old, local resident, p. Kurai]. | “The imprint is made by mountainous terrain, the landscape itself, medium mountains, over 1000 m, all settlements are located at an altitude of over 1000 m. It turns out that we are completely in the mountains, and accordingly we have our own specifics and nuances that leave an imprint in connection with the weather and climatic conditions and the landscape itself, well, in fact, our difficulties. …. And in this regard, we have many such moments here that are not found in other regions. First of all, these are infrastructural aspects, the transport component, energy, communications. Well, all this comes to us on the sly. The road appeared only in 92 ”[Male, administration worker, 49 years old, Orlik]. |

| “The fact that our village is remote is even good. Nobody bothers, there is a lot of space. It used to be a big village. When the road to Kuyus was made, we had no young people left here. They began to leave. First, to earn money in Chemal (there are a lot of tourists, you can always earn money), and then they stay there forever. And who, in the City (Gorno-Altaysk-author) will go to study. At first, every week they come home-there is a road. And they don’t come back after school either” [Male, 62 years old, local resident, Edigan]. | “In transport, in healthcare, everyone has the same problem. If there was a regular bus, we would know that it will come on Wednesday and we would book for Wednesday to the doctor, to the tax authorities in general to all authorities. It’s hard to get to the hospital. Still by appointment. And so they will write us on September 25, and we do not know whether there will be a car at that time. Transport and healthcare are interconnected. Poor transport accessibility. While you leave. You need to find a taxi. Or negotiate with someone. No regular buses. Nothing" [Male, local, 63 yearsold, Ust-Urkima]. |

| + Positive Attitudes | − Negative Attitudes |

|---|---|

| “We have a regional road, we have always had it, in which we were lucky that we have a regional road” [Female, administration worker, 38 yearsold, Ust-Urkema]. | “I think it’s good that we didn’t make the road, anyway there is a deterrent factor in any case. Even now, people are driving in bulk, and even though the road is bad… they also catch our natural resources, kindle fires. It has become very fashionable to come by motorboats and ride to frighten fish” [woman, 47 years old, employee of a cultural institution, p. Orlik]. |

| “Of course, without (Chuisky-author) the tract there would be no life here. Almost everyone has a job with him. Even those who graze cattle, then take them (cattle-author) to take them to Kosh-Agach or to the City (Gorno-Altaysk-author). Here, dealers accept it very cheaply. Well, tourists, of course, go. Now many people make money on tourists. You can earn a lot in the summer season.” Vyacheslav (village of Kurai) | “You can’t build this road to China. There (on the Ukok plateau-author) our ancestors rest. This is a sacred place. When archaeologists got Ms. Ukok (the mummy of a Pazyryk noble woman, excavated by the archaeological expedition N.V. Polosmak in 1993-author), an earthquake occurred, which almost destroyed my native village (Chuy earthquake of 2003 with a magnitude of 7.3 on the scale Richter, who destroyed the village of Beltir-author) [Male, 42 years old, local resident, p. Beltier]. |

| “In the sense from Tynda to us, the road is generally ugly. When they do it then it’s okay, but it’s basically a bad road. Yes, not long ago there was a prosecutor, that’s why they did it. This summer the road was very bad because of the rains. Now the road from Larba to Urkema has been made. It is better than all this one, because they carry schoolchildren.” Female, local, 62 years old, Ust-Urkema | “If a road to China is built, it will become cramped for us here. All the Chinese will occupy. And the first thing that they will do—they will take all our nature into our pockets. They are the ones in their country who treat nature with care, and they do not feel sorry for someone else’s. We will have neither leopards nor ibex. No one” [Male, 34 years old, local resident, p. Kurai]. |

| We have seen ourselves that we have a road, asphalt in the area, and then a dirt road, in 2023 it will be asphalted. We are looking forward to it because we crash cars [Female, administration worker, Pervomaisky]. | “Nobody will allow to build roads here (in the valleys of the Akkol and Taldura rivers). This is our land. We won’t let anyone in here. If tourists need it, we will take them ourselves. We also need to live somehow” [Male, 42 years old, local resident, p. Beltier]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuklina, M.; Dirin, D.; Filippova, V.; Savvinova, A.; Trufanov, A.; Krasnoshtanova, N.; Bogdanov, V.; Kobylkin, D.; Fedorova, A.; Itegelova, A.; et al. Transport Accessibility and Tourism Development Prospects of Indigenous Communities of Siberia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031750

Kuklina M, Dirin D, Filippova V, Savvinova A, Trufanov A, Krasnoshtanova N, Bogdanov V, Kobylkin D, Fedorova A, Itegelova A, et al. Transport Accessibility and Tourism Development Prospects of Indigenous Communities of Siberia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031750

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuklina, Maria, Denis Dirin, Viktoriya Filippova, Antonina Savvinova, Andrey Trufanov, Natalia Krasnoshtanova, Viktor Bogdanov, Dmitrii Kobylkin, Alla Fedorova, Anna Itegelova, and et al. 2022. "Transport Accessibility and Tourism Development Prospects of Indigenous Communities of Siberia" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031750

APA StyleKuklina, M., Dirin, D., Filippova, V., Savvinova, A., Trufanov, A., Krasnoshtanova, N., Bogdanov, V., Kobylkin, D., Fedorova, A., Itegelova, A., & Batotsyrenov, E. (2022). Transport Accessibility and Tourism Development Prospects of Indigenous Communities of Siberia. Sustainability, 14(3), 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031750