1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on various areas of economic and social life. In the area of logistics, problems like broken supply chains have been observed. However, these are short and medium-term disruptions to which companies try to respond on a regular basis. There are, however, questions about the future of supply chain strategies and about the impact of the changes that will follow, on the ecological and social aspects. Finding answers to these questions is the research problem of this article.

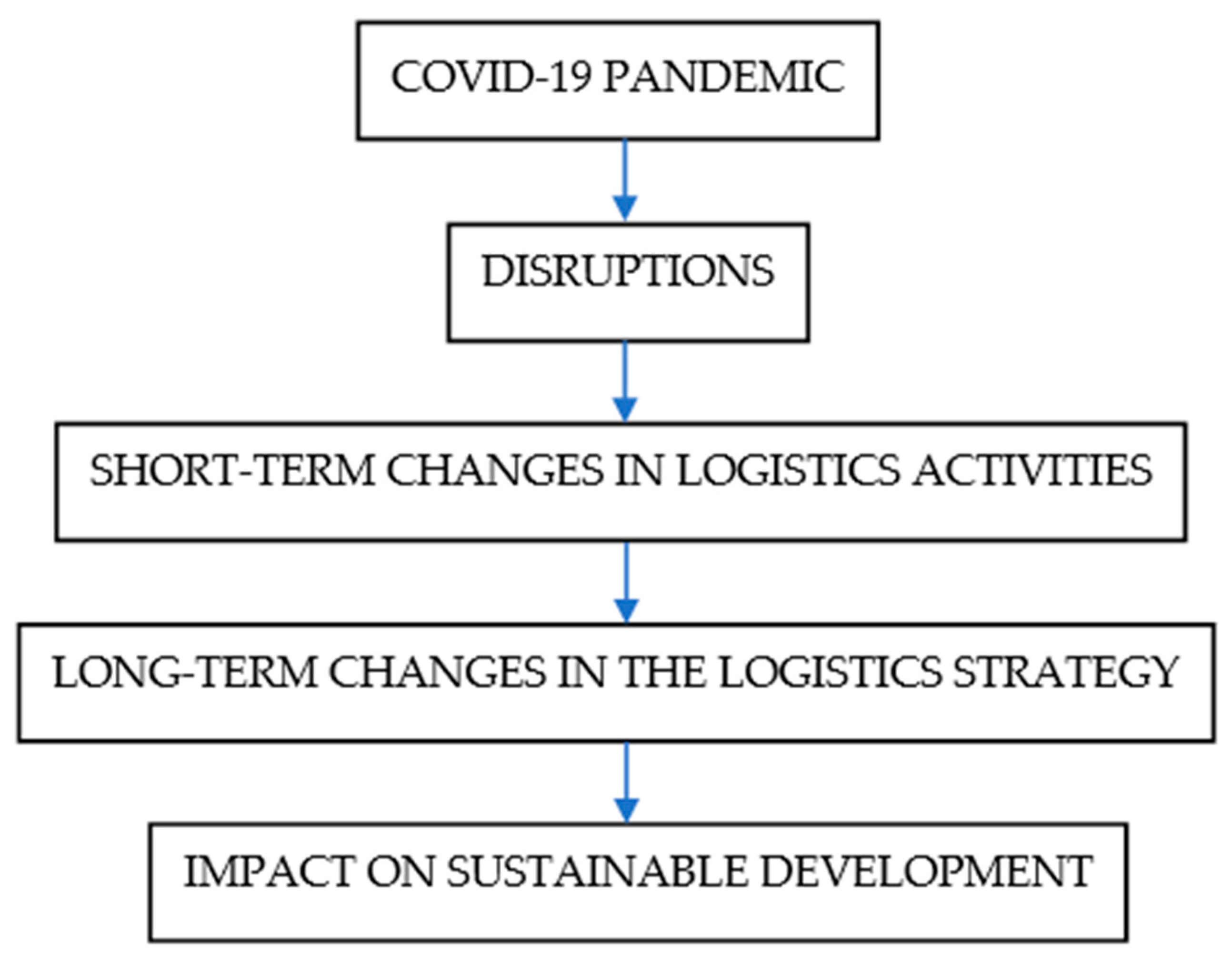

The author focused on the clothing industry, which was particularly hard hit by the pandemic. Therefore, the main goal of the article is to present the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the functioning of the supply chains of Polish clothing companies in the short and long-term aspect in the context of sustainable development. The questions asked by the author concerning the impact of the pandemic on the functioning of supply chains in this industry (

Figure 1) are as follow:

What disruptions in the supply chains did the COVID-19 pandemic cause in the clothing industry?

How did this affect the functioning of supply chains in the clothing industry in the short term?

Will the logistic concepts and strategies previously used in this industry be changed as a result of the pandemic?

How will the long-term changes caused by the pandemic affect sustainable development?

The author’s hypothesis is as follows: In addition to its short-term effects, the pandemic will also have strategic long-term effects on the supply chains of apparel companies.

This issue is very important as the next waves of the COVID-19 pandemic are coming, and individual companies are trying to adequately respond to the disruptions caused by the pandemic. Individual industries are affected by the pandemic to a different degree. The industry that has been severely affected is the clothing industry, on which the author focused her research. However, even when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, it is likely that further disruptions, such as those caused by economic crises, will occur. Since the global crisis in 2008, we know that the economy is less stable and less predictable than previously thought. Disruptions in supply chains can also be caused by phenomena not only on a global but also local scale, such as, for example, strikes or natural disasters, such as earthquakes or tsunamis. Therefore, it is important to study the impact of disruptions caused by a pandemic on the supply chains of clothing companies and to study not only the short-term response to disruptions, but most of all long-term changes in logistics strategies. It is also important to present how these changes will affect sustainable development in the long term.

The research conducted by the author is based on interviews conducted in Polish clothing companies. The author also presented a case study—the impact of the pandemic on the distribution of the largest Polish clothing company, LPP S.A.

The topic taken up by the author is important both from a theoretical and practical point of view. The clothing industry is one of the most important branches of the world economy, is one of the most globalized and has a large impact on the natural environment. The research is innovative and fills the existing research gap.

2. Review of the Literature

Disruptions in supply chains have been the subject of research for many years [

1,

2,

3]. Research on the risk of disruptions in the supply chains conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic indicated following threats, e.g., environmental disasters, terrorist attacks, globalization, unpredictable changes in demand, shorter product life cycles, reducing the number of suppliers, reducing buffers (inventory, time), integrating processes between enterprises, on-time delivery, increasing outsourcing and offshoring, dependence on suppliers [

4]. Thus, these are both reasons independent of enterprises and resulting from the applied strategies of supply chains.

Research is currently being conducted around the world on the impact of the pandemic on supply chains. For example, Dąbrowska et al. [

5] presented the issues of the risk management in the supply chain in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is believed that the COVID-19 pandemic unveils unforeseen and unprecedented fragilities in supply chains and because of that the adaptation capabilities play the most crucial role in managing the SCs during pandemic [

6]. According to some authors [

7] the pandemic triggered supply disruptions, but did not significantly impact the productivity of manufacturing firms.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a cause of disturbance independent of companies, but its impact on supply chains depended heavily on the strategies of these chains, e.g., whether these chains are local or global. Many authors indicate that disruptions in global supply chains have been greater than in the local ones. For example, according to Ivanov [

8] industries that are highly globalized are especially prone to epidemic disruption. Because of COVID-19 pandemic supply of a wide range of raw materials, intermediate goods, and finished products have been seriously disrupted especially in global supply chains [

9]. Because the global production and the global supply chains are mostly disrupted due to the widespread coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, some authors propose strategies for improving the resilience and sustainability of the system [

10].

According to McMaster et al. [

11] the optimal SCM structure largely depends on firm-specific characteristics and flexibility and diversification is the best way to hedge this risk. Furthermore, according to [

12], a flexible production structure is vital to effectively address unpredictable turnarounds of the market in a timely manner.

The fashion SC is geographically complex and prone to epidemic disruption and its consequences [

13,

14].

Clothing is mainly sewn in low-cost countries. Rising wages in China over the past decade was the reason for relocation of production to countries such as India, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. The textile and fashion industries have come to rely heavily upon developing economies for low-cost sourcing and manufacturing and are therefore particularly at risk of the aforementioned disruptions [

15].

According to Lu, many fashion companies in the United States source from multiple countries to reduce the risk and explore near shoring opportunities to bring flexibility [

16]. Industry practitioners and researchers say that this pandemic will not only affect the industry in the near future but may also have a long-term impact [

17]. The allocation of production may result from rising costs in the countries of the South-East Asia. For example the production cost even in Bangladesh increased during the pandemic [

18].

According to research conducted at the Polish Economic Institute on the impact of the pandemic on globalization, global supply chains have proved to be inelastic in the face of demand and supply disruptions and growing problems related to maritime transport. However, according to these studies, despite the disruptions, only 6 percent of respondents declared that they are involved in shifting supply chains from China [

19]. Reallocation of supply or production is not easy.

Research conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that production in the low-cost countries would become unprofitable if shipping costs increased significantly, purchasing costs in low-cost countries increased, or if demand is difficult to forecast [

20]. During the pandemic, the rates for shipping containers from Asia to Europe increased up to four times [

21,

22], the quality of deliveries measured with time and their timeliness also deteriorated. This may result in the allocation of production closer to the selling market. However, according to the research conducted by D. Milewski, even despite the actual increase of the shipping rates in maritime transport, the production in the low-cost countries is still profitable. However, the greater the fluctuations and the lower the predictability of demand, the greater the profitability of deliveries using air transport but also local deliveries [

23].

The disruptions caused by the pandemic not only affected the supply and production, but also affected distribution and sales, especially in e-commerce. Research conducted by Gemius at the turn of May and June 2021 in the field of e-commerce shows that the lockdown introduced in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic changed the consumer behavior of Poles: 30% of respondents buy more products online, 33% buy online more often and for 13% of respondents, the internet has become the first-choice purchase channel. The same research indicates that for 62% of respondents, the motivating factor to buy online is the ability to do shopping when stores are closed (lockdown). Clothing and accessories are the most frequently chosen category of products ordered online (72%), shoes are in second place—61% [

24].

Weber conducted very interesting research concerning e-commerce. She explored the major supply chains disruptions experienced by South African omnichannel retailers because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the response strategies employed by the retailers. The study found that omnichannel retailers experienced external and internal supply chain disruptions during the pandemic. The most noticeable external disruption was the drastic migration of consumers to online channels and the retailers’ inability to meet demand surges [

25].

Clothing is sewn in low-cost countries, especially Bangladesh, and sold in highly developed countries. During pandemic, the demand for clothing was reduced. That caused substantial decrease in the production of the textile and apparel product, which led ultimately to shutting down factories and laying off workers [

26]. Moreover, during the lockdown, a few factories continued their production without ensuring safety [

27]. Furthermore, global fashion retailers had to dismiss garment workers, but there were different responses to external and internal crises during the pandemic [

28].

The strategy used in the clothing industry in many of the largest companies in the world is Quick Response [

29,

30]. Before the pandemic, the largest Polish clothing companies used only certain elements of this strategy. For example, according to the author’s research from 2017, the largest clothing company in Poland—LPP S.A.—used a pull flow (i.e., deliveries regulated by actual demand) only in the section from the distribution center to the stores. Each store informed about demand and received the clothing exactly according to demand. Deliveries to stores were performed frequently in small quantities. However, Polish companies generally did not use the pull flow in the section between the sewing rooms and the distribution center because the clothing is usually produced and shipped from the low-cost countries. Therefore, the clothing was ordered well in advance according to forecasts [

31]. The huge geographic distance between the place of production and outlets means that the average time from the preparation of collection designs to placing products on store shelves is 6–9 months [

32].

It is also very important to include sustainable development in research. According to Tirkolaee et. al., recently, large companies have shown a growing tendency to enhance sustainability of their supply chains [

33].

The author has been conducting research in the clothing industry in Poland since 2017. These studies focused on supply chain models and strategies [

34], sustainable development [

35,

36], logistics services [

37,

38], maritime transport in supply chains [

39], quality [

40] and relationships of supply chain participants in the clothing industry [

41].

Based on the above literature review, it can be concluded that there is a fairly widespread perception that a pandemic will bring about a fundamental change in supply chain strategies. Supply chains are to be more flexible, production is to be reallocated from low-cost countries to Europe. Meanwhile, statements by representatives of companies from highly globalized industries, i.e., automotive and clothing, seem to contradict it.

Therefore, the question is what the actual long-term effects of the pandemic on the functioning of the apparel supply chains will be, and how it will affect sustainable development. The aim of this research was to find answers to these questions. Thus, although research on the clothing industry has been conducted before, the novelty of the research presented in this article is the presentation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clothing industry, in particular on supply chains. This research presents not only the disruptions caused by the pandemic, but also the short-term response of companies and possible long-term actions and their impact on sustainable development. Thus, this research fills the cognitive gap.

3. Materials and Methods

The article presents the results of research carried out in Polish clothing companies during the pandemic.

The author has been researching the logistics and production processes and supply chains of Polish clothing companies since 2017 (direct interviews with company management, observation). Research on the impact of the pandemic on the functioning of logistics in this industry of the economy was carried out in 2021 and took the form of telephone interviews.

An interview as a research method has the advantage over a questionnaire survey, because it can be more accurate and can better take into account the specificity of each of the surveyed companies. The respondent has the opportunity to answer the question in great detail, and the researcher has the opportunity to ask many additional questions, deepening the research. In the author’s opinion, the interview method may also be more reliable when it comes to the obtained answers. The researcher has the opportunity to check whether the respondent understood the question correctly and whether he understood the respondent’s answer correctly. This was the reason why the author chose this research method. However, this is a much more time-consuming study, both in terms of interviewing and processing the results.

Telephone interviews were conducted in two stages—in April 2021 (when clothing companies in Poland had already experienced two lock-downs) and in November 2021 (the acceleration of the fourth wave of the pandemic in Poland). The questions concerned the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individual supply chains of individual companies in the garment industry, in particular on procurement, distribution, manufacturing, inventory maintenance and transportation (

Figure 2).

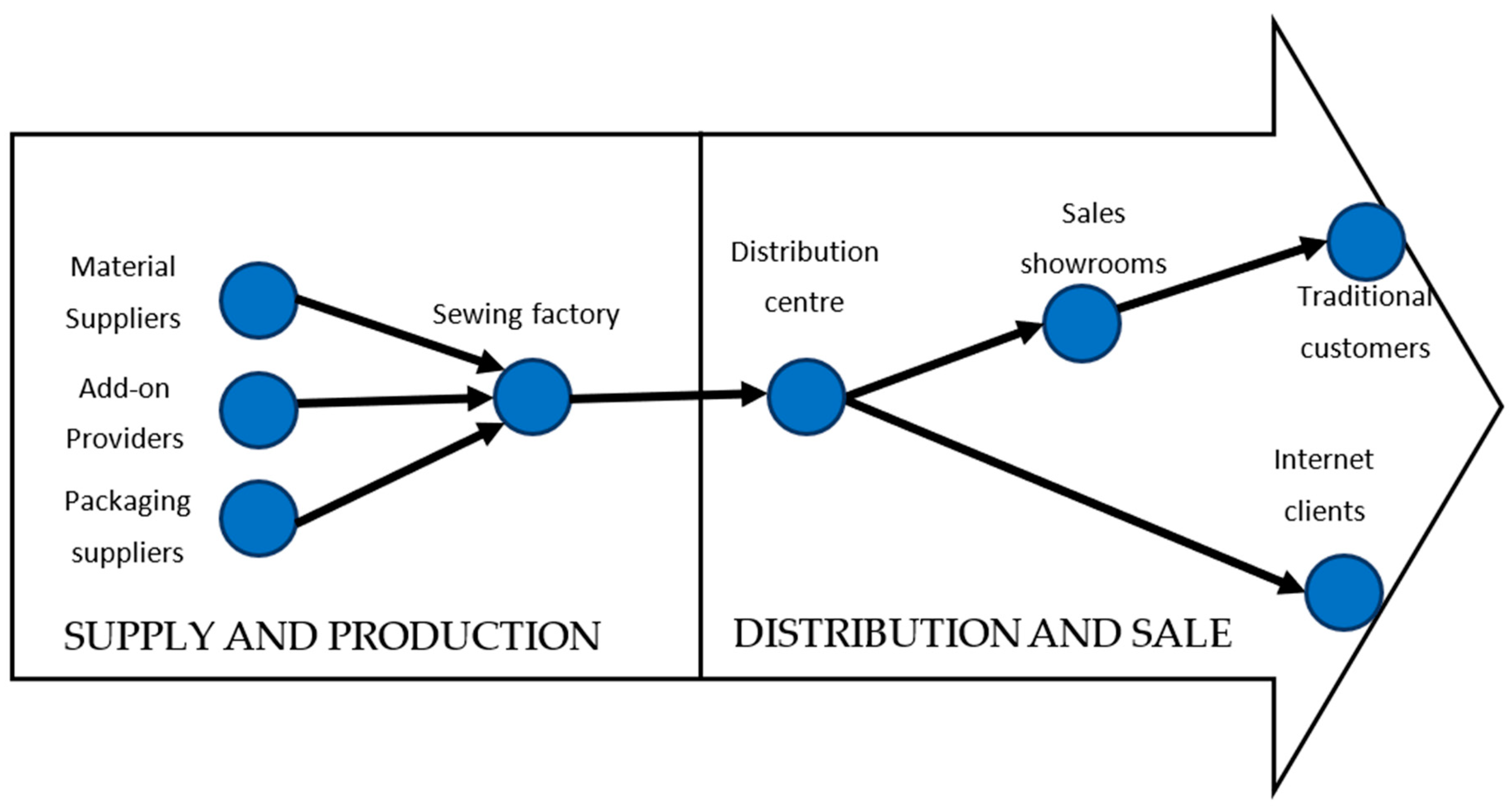

Polish clothing companies are diverse, but one can divide them into groups that the author identified during previous research. Polish clothing companies can be divided primarily according to the criteria of functions in the supply chain (supply chain leader or participant) and the type of activity that the company conducts (manufacturer or distributor). The author interviewed three typical groups of Polish clothing companies:

Distribution companies that are leaders of the supply chains,

Production companies that are leaders of the supply chains,

Production companies that are participants of the supply chains (

Figure 3)

Supply chain leaders are often distribution companies that outsource the production of clothes according to their own designs to sewing factories (very often located in countries with low production costs), and then distribute and sell them in their own networks of showrooms, as well as via the internet. According to this model, the largest Polish clothing companies operates. There are few companies like this in Poland, but they have a very large share in the Polish clothing market. An example of a company from this group, in which the author conducted the research, is the largest Polish clothing company, LPP S.A.

Supply chain leaders are often also production companies, sewing clothes in their own sewing factories according to their own designs, under their own brand. They sell these clothes, usually through traditional stores, which usually do not belong to them, or in online stores. These mainly medium and small companies.

The participants of the supply chains who are not leaders are mainly production companies (sewing plants), sewing on behalf of the leaders of supply chains according to their projects. There are a lot of companies like this in Poland. They are medium-sized or small companies. They receive orders mainly from distribution companies that are leaders in the supply chain, but also from other production companies, e.g., in the case when they have too many orders.

The author conducted research in all three groups of companies. In the group of distribution companies that are leaders in supply chains, the author chose the largest companies listed on the stock exchange. In the group of medium and smaller companies, the author searched for companies on the internet. The respondents were informed about the purpose of the interview and gave their consent to it.

During her research, the author used a general list of issues that she had prepared earlier, but depending on the answers provided, many detailed questions were added after each general question. Some of the issues from the general list concerned all companies, and some only specific types of companies.

Table 1 presents a general list of issues, broken down into issues for all companies and for individual types of companies.

As mentioned before, each general question was followed by specific questions, for example, to know the size and duration of the disruption, the effects of what the disruption caused, and how companies responded to disruptions.

Section 4 presents the impact of the pandemic on the supply chains of Polish clothing companies, based on the data from the interviews. The supply chains have two parts: part of the supply and production and the part of distribution and sales (

Figure 4). The impact of the pandemic on distribution and sales was described first. Then the impact of the pandemic on supply and production was described.

The impact of the pandemic on the distribution and sale of clothing in Polish companies is presented in the

Section 4.1. In the

Section 4.2 a case study is presented on the impact of the pandemic on distribution in the largest Polish clothing company LPP S.A., with particular emphasis on strategic changes in distribution logistics. The

Section 4.3. presents the impact of the pandemic on the production of clothing in Polish sewing factories and their supply. The

Section 4.4 analyzes which changes caused by the pandemic will be associated with long-term changes in the logistics strategy. The

Section 4.5 presents what will be the impact of strategic changes in the logistics of clothing companies on sustainable development.

4. Results—The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Clothing Industry Based on Own Research

4.1. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Distribution and Sale of Clothing

COVID-19 caused problems in the distribution and sales in all surveyed groups of companies: both distributor companies, private label manufacturers and manufacturers which sew for orders. However, not all companies experienced this problem with the same intensity.

The impact of the pandemic on the distribution and sale of clothing in individual companies in Poland depended primarily on the following factors:

location of showrooms (in shopping centers or outside of them),

the possibility of selling clothes to customers ordering via the internet (e-commerce),

the geographical distance between companies in the distribution channels, mainly between the sewing factories and the distribution center,

the mode of transport with which the goods are transported from the sewing factories to the distribution center.

Firms that sell their clothing in showrooms located in shopping centers were more affected by the pandemic because during the lock-down shopping malls were closed. The largest Polish clothing companies have their stores in shopping malls. These companies generally outsource the production of garments well in advance, because many of the sewing factories they work with are located in low-cost countries and delivery times by sea are long. During the lock-down, larger inventories of clothing began to build up in the distribution centers of these companies, because the deliveries of new products from manufacturers had arrived and sales decreased.

Polish sewing plants, which sew products under their own brand, are usually small or medium-sized. They usually do not sell their products in shopping malls. Despite the closing of shopping malls, their stores could be open. As a result, some of them had even more sales than before the pandemic, as some of the customers who had previously shopped in shopping malls started to buy clothes in the little shops.

Because of the lockdown and the closing of shopping malls, but also because of, for example, quarantine or fear of the possibility of getting infected in the store, many customers bought clothes primarily online. So there was a rapid development of e-commerce. Companies that sold clothing online before the pandemic had a better opportunity to develop this area than companies that only sold clothing in traditional stores. However, even in a situation where e-commerce sales were well-organized before the pandemic, problems with the quality of deliveries to online customers often began to emerge due to the sudden expansion of this distribution channel. Some companies that had little or no internet sales before the pandemic tried to expand it during the pandemic, but encountered difficulties.

Another problem was disruptions in the supply of clothing from sewing factories to distribution centers. These disturbances mainly occurred when there is a long geographic distance between the sewing factories and a distribution center. Therefore, this mainly applies to companies that outsource production to sewing plants located in countries with low production costs, while their distribution center is located in Poland. In connection with the pandemic, there were often delays in deliveries, caused for example by quarantine in the port or on the ship, on which containers with clothes were transported. In addition, during the pandemic, the rates of maritime transport increased significantly, which, in addition to disruptions in supply, is another factor that reduces the profitability of production in countries with low production costs.

4.2. Disruptions and Changes (Short and Long-Term) in Distribution Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Largest Polish Clothing Company, LPP S.A.

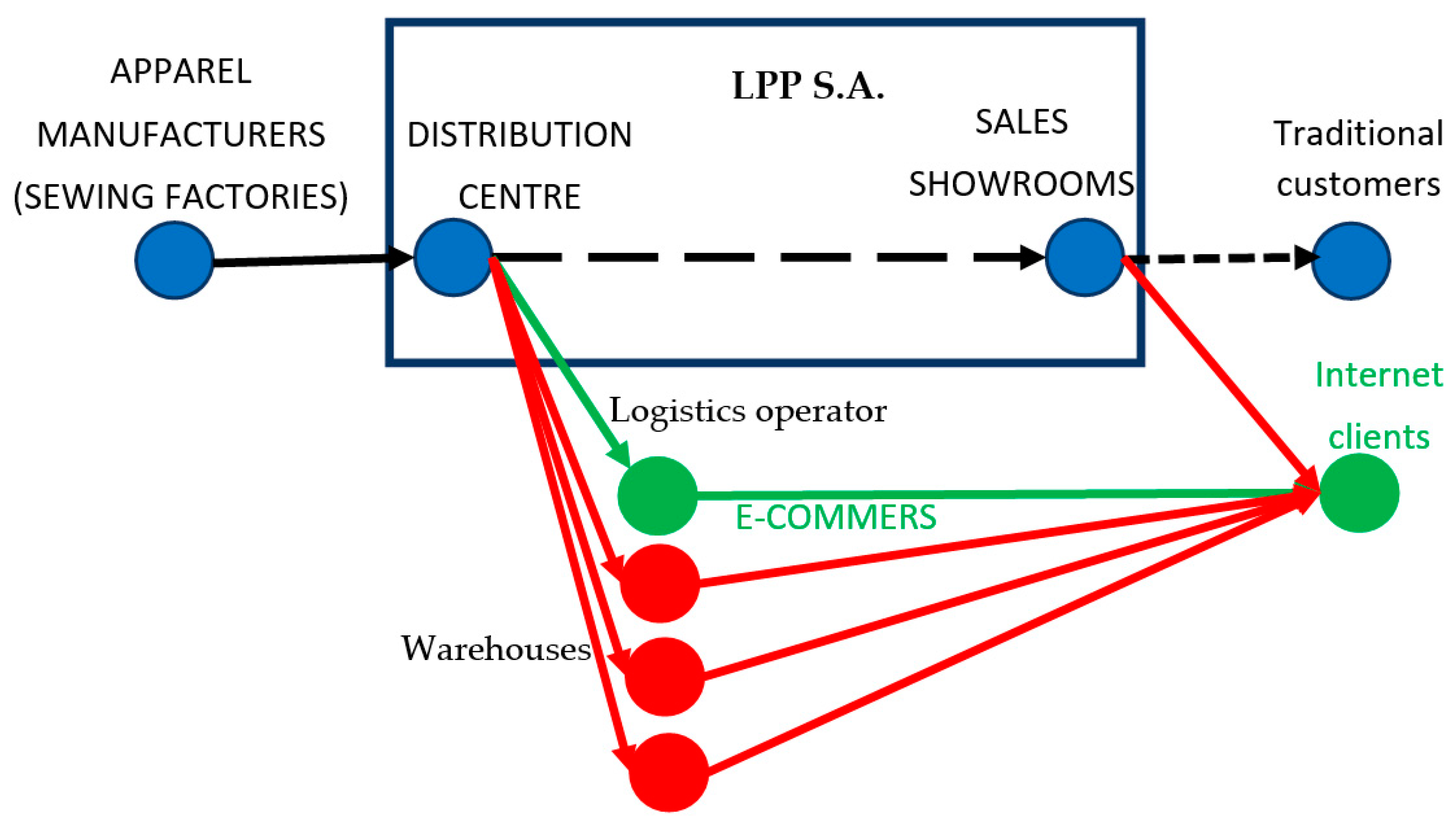

The largest Polish clothing company, LPP S.A., deals with the distribution and sale of clothing in its own extensive network of showrooms (located not only throughout Poland, but also in most of the European countries and in Middle East) or via the internet. This company outsources production according to its own designs and under its own brands to sewing factories, usually located in countries with low production costs, e.g., Bangladesh, although it also cooperates with sewing factories in Poland. The products are shipped from the sewing factories to its own modern distribution center and then to the network of its own stores. Transport from the distribution center to the showrooms is carried out by the courier companies. The location of the distribution center was dictated by the proximity of the port, as the delivery of clothes from low-cost countries is mainly by sea.

The company also sells clothing to online customers. Before the pandemic, the sales to internet customers were growing slowly but systematically. Deliveries to online customers were handled by a logistics operator specializing in e-commerce, which organized the delivery of clothes to internet customers from its own warehouse. Traditional distribution and e-commerce at LPP S.A. before the pandemic is shown in

Figure 5.

The pandemic and the related lock-down primarily affected the company’s distribution. Almost all of LPP S.A.’s showrooms are located in shopping malls. Due to the closing of shopping malls, traditional sales were not possible. Deliveries from the distribution center to the showrooms were not performed. At the same time, the number of orders from online customers has increased very sharply. Such a rapid increase in internet sales could not be handled by the logistics operator that has been dealing with it so far. Therefore, an additional distribution channel for clothes to internet customers was created—these deliveries were also carried out by its own distribution center. During the first lock-down, internet customers were thus served in two ways—not only, as before the pandemic, by the logistics operator, but also by their own distribution center (

Figure 6). However, the transport itself, as before the pandemic, was carried out by courier companies.

However, its own distribution center was not prepared to handle orders for online customers, as so far it had only performed deliveries to showrooms. Deliveries to online customers have a different specificity than deliveries to the store. They are less predictable, they have to be dispatched quickly and without mistakes as to garment type, size, color, etc. Consequently, online customer service has deteriorated. In order to improve the level of online customer service, after the first lockdown, the company was intensively preparing for the next lockdowns. Therefore, the planned and already started investments were accelerated. When the next lock down took place, internet customers could, in addition to the current logistics operator, be served by three new warehouses—one in Gdańsk, and two intended for deliveries to customers outside Poland—located in Slovakia and Romania. Selected showrooms were also involved in serving customers who placed an order via the internet. It is presented in

Figure 7. Due to the expansion of the warehouse infrastructure from which deliveries to internet customers could be made, the level of their service improved. The company is also well prepared for the anticipated further growth in online sales.

To sum up, on the example of LPP S.A. the following stages of responding to a crisis situation caused by a pandemic can be distinguished:

stage one—initial, short-term response, immediate measures. In the described case, it consisted of creating a temporary distribution channel to internet customers using the company’s own Distribution Center, which was previously used for deliveries to its own showrooms. The first reaction was not related to strategic and long-term activities, because when the lock-down was over, the distribution center could return to its previous tasks and started again, as before the pandemic, deliveries to showrooms.

stage two—a long-term change in the logistics strategy. In this case, the change concerned the distribution strategy and was related to the expansion of the distribution network with new warehouses from which deliveries to internet customers could be made. The company qualified the change caused by the pandemic as permanent, requiring strategic action, and time has shown that it was the right thing to do.

4.3. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Production of Clothing in Polish Sewing Factories and Their Supply—Based on Own Research

The impact of the pandemic on the production of clothing in Polish sewing factories and their supply depended on the following factors:

the type of a sewing factory (factory sewing clothes under its own brand or sewing on orders of an another company),

in the case of a sewing factory sewing for an order of another company—on the possibility of selling clothing during a pandemic by the company ordering the production,

the type of clothing,

type of supply goods (e.g., materials and additives) and source of supply.

Sewing plants in Poland are usually medium-sized or small companies. They can be divided into two groups: companies sewing clothes under their own brand, usually according to their own design, and companies sewing to an order, according to the design of other companies, usually from materials provided by these companies. In both groups of sewing factories, most of the employees work directly in production, production is not automated. Employees work in close proximity to each other, so it is difficult to maintain a sanitary regime. As a result of the pandemic, some Polish sewing factories suffered from a periodic shortage or reduction in production capacity (e.g., quarantine). The tendency to reduce the production capacity of Polish sewing factories was already felt in Poland for a long time in connection with the lack of schools educating sewing workers. The pandemic intensified this problem. Therefore, some sewing factories were looking for subcontractors, both in Poland and in other countries, e.g., in Belarus or Ukraine (due to the proximity and lower labor costs than in Poland). However, there were also sewing factories that did not experience any greater absenteeism of employees.

Another problem took place only in sewing factories that sew to order. During the pandemic, there was a significant decrease in production orders from contractors, in some cases even by over half. It especially affected those companies, that sewed for many years only on behalf of companies from West Europe. Prior to this, they did not have to worry about selling, designing, or acquiring materials (because they sewed clothes from materials provided by the contractor). This reduction of orders was a very difficult situation for them. Some of these companies described their situation during the pandemic as “tragic”. These companies tried to establish cooperation with new contractors—mostly Polish. Some of these companies started sewing according to their own designs and selling clothes on their own, but encountered difficulties with selling.

There were also sewing factories that did not experience a decrease in demand for their clothes during the pandemic. In the group of companies sewing under their own brand, these were companies that sold clothing not in the shopping malls but in small shops. It also depended on the type of clothing produced. For example, a medical clothing company did not experience a decrease in sales.

Of course, sewing factories, in order to be able to produce, must have the necessary materials, accessories and packaging. Because of the pandemic, periodical shortages of some supply goods (e.g., materials, additives, cardboard packaging) were observed in many companies. These problems were caused e.g., by quarantine at a sub-supplier or delays in deliveries, e.g., from the Far East. There was also a significant increase in the prices of many materials (e.g., fabrics, yarns, packaging, accessories). Due to the projected further price increases and the risk of supply disruptions, some manufacturing companies have started to build up larger supply stocks.

There were also situations that companies outsourcing production to sewing factories, despite the slump in sales and the lack of production orders, still bought and sent materials for production, due to the expected increase in prices. The sewing companies had to store these materials.

There were also some companies that did not experience any supply problems due to the pandemic.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Polish manufacturing companies (sewing factories) is presented in a synthetic way in

Table 2.

4.4. Long-Term Changes Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Garment Industry

Based on the conducted research, it can be concluded that the pandemic caused disruptions in supply chains, both in the of supply and production, as well as in distribution and sales. Individual companies had to react to emerging disruptions or the risk of disruptions on an ongoing basis. For example, due to anticipated supply disruptions and anticipated further increases in the prices of materials, firms built up stocks of these goods. In the case of the impossibility of production due to illness and quarantine of employees—they were looking for subcontractors. In the case of an absence of orders—they were looking for other contractors. However, these were mostly current, short-term or medium-term measures.

However, the question arises whether the pandemic has led to long-term changes to the logistics strategies previously used in this industry, or at least elements of this strategy?

According to the author, the long-term change will concern distribution channels. The increased share of online clothing sales in comparison to sales in brick-and-mortar stores will continue to grow also after the pandemic, although not so rapidly. The increase in sales to online customers has been visible for a long time before the pandemic, but the pandemic has intensified this trend. Due to the closing of the shopping malls, clothes began to be bought online by people who previously bought only in traditional stores. Many of these people found out about the convenience of this form of sale and stayed with it even after opening stores. Maintaining this trend after the pandemic is also anticipated by the management of most of the surveyed companies. For this reason, companies take actions such as the expansion of warehouse infrastructure for deliveries to internet customers. These are the changes of strategic character.

Another change in the logistics strategies of clothing companies, expected even before the pandemic, which has not yet occurred on a larger scale, is the reallocation of production from low-cost countries to Europe. Large Polish distribution companies that are supply chain leaders sewed some clothing in Poland or a region (Eastern Europe, Turkey) even before the pandemic, but it was usually more expensive high-quality clothing or fashion hits that had to be quickly delivered to the market. However, most of the clothes were sewn in the Far East and so far the production has not been reallocated. Favorable conditions for this allocation may be caused by the pandemic. Local production means lower risk of disruptions in supply chains and lower transport costs (shipping costs quadrupled during the pandemic). The reallocation of production closer to the sales markets (to Poland or at least to the region of Eastern Europe) is a condition for the production of clothing in accordance with the actual demand identified in the showrooms, not to stock. So it would be possible to apply this element of the Quick Response strategy. The advantages of producing locally and according to actual demand, are lower costs of maintaining inventory, better logistics customer service and lower transport costs. The disadvantage of reallocation is undoubtedly higher production costs in Europe than in the Far East, e.g., in Bangladesh. The condition for mass transfer of production to Poland is the increase in production capacity, which is difficult due to the lack of sewing workers. Production in Eastern European countries (e.g., Ukraine or Belarus) would be cheaper than in Poland, although more expensive than in the Far East, but it could be associated with possible disruptions due to the unstable political situation in this region.

For the time being, however, according to the majority of companies that participated in the survey, a mass transfer of clothing production from countries with low production costs to Poland is unlikely. One of the medium-sized companies surveyed even declared that despite the fact that so far it has sewed clothes in Poland or in Eastern Europe, now, due to costs, it is considering outsourcing part of the production in the Far East, and sewing only more complicated clothes in Poland. So it seems that despite the disruptions caused by the pandemic, the benefits for many companies from lower labor costs in the Far East still outweigh the increased costs of transportation, inventory maintenance and the risk of disruptions and shortages. Mass reallocation of clothing production to Eastern Europe could take place in the event of an increase in disruptions in supplies from Southeast Asia and a further increase in the costs of sea transport under condition stabilization of political situation in the Eastern Europe.

Another change that occurred in connection with the pandemic in Polish clothing companies, and which may be of a long-term character, is the change in relationships in supply chains. Until now, many relationships between individual companies have been relatively durable. For example, many Polish subcontracting companies had regular clients, e.g., from Western Europe. On the other hand, Polish distribution companies usually cooperated with the same sewing factories. The pandemic, causing disturbances (e.g., reduced demand for clothing resulting in a lack of orders; quarantine in sewing factories resulting in the lack of production potential) forced greater variability and flexibility of the relationships. In many cases, companies were forced to look for new contractors. Some companies also started to undertake new activities, for example a company that had so far only sewed on behalf of other companies and under their brands, began to sew and sell its own products. Cooperation with new contractors or taking new actions was, in the pandemic, rather ad hoc, but perhaps also after the end of the pandemic supply chains will be more flexible. This means that, for example, sewing factories that have so far been associated with the same contractors for many years may look for other activities. So perhaps supply chains will implement the Agile strategy.

Changes in the supply chains of Polish clothing companies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which are or may be long-term and strategic in nature, are presented in

Table 3.

4.5. The Impact of Long-Term Changes Related to the Logistics Strategy Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Clothing Industry on Sustainable Development

A change that has already taken place caused by the pandemic that could impact environmental and social aspects is the increase in the share of deliveries to internet customers. The impact of this change on environmental pollution is ambiguous.

In comparison to the deliveries to shops, the deliveries to online customers means deliveries of small amounts of clothing to many different locations, which generates more kilometers traveled and more environmental pollution. However, increasing the volume of deliveries to online customers due to the pandemic means that one courier serves a smaller area and the customers are closer to one another, making the negative environmental impact of the increase in these volumes less than proportional [

42]. It also results from the research conducted by the author of this paper [

43]. In addition, in Poland, the collection of parcels ordered online in parcel lockers is very popular. A large number of parcels are delivered to the parcel lockers at one time, so the number of kilometers traveled and the pollution of the environment is smaller than in the case of deliveries to customers’ homes.

However, both in case of buying in traditional stores and collecting parcels from parcel lockers, it should also be taken into account how customers travel to collect a parcel—e.g., with their own car, public transport or on foot, whether they will get there on purpose or by the way. e.g., returning from work.

When it comes to the environmental impact of e-commerce in the case of clothing, it should also be taken into account that many customers order more clothing than they really want to buy. After trying them on, they leave only what suits them best and send the rest back. The costs of transporting the returned clothing are generally free in Poland, and a courier comes to the customer’s home to collect the returned package. However, this generates costs for companies, but also increases the number of transports, and thus greater environmental pollution.

The impact of increasing the sale of clothes via the internet on social costs may relate primarily to the labor market. In the long term the demand for employees of stationary clothing stores may decrease, and increase for couriers.

The second permanent change, reallocation of production from low-cost countries to Europe, if it were done, would have a positive environmental impact. The place of production of the clothes would be much closer to the market. Transport over much shorter distances would cause less environmental pollution.

The impact of the allocation of production on social costs may relate primarily to the increase in the demand for sewing workers in Poland (or in Eastern Europe), and smaller—in the Far East.

The third change in strategic character in the context of the pandemic can be the increase in the flexibility of relations of participants of supply chains. The impact of this change is so far difficult to assess in the long term. The changes observed in connection with the pandemic, such as a decrease in production orders from regular contractors in a given sewing factory and the need to search for new orders, contributed to a less stable situation for employees (social aspect). The cooperation of sewing factories with different subcontractors increased the number of transports (ecological aspect), but the impact on the natural environment depended on the subcontractor’s location.

The impact of changes in the logistics strategy of clothing companies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable development is presented synthetically in

Table 4.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The author, on the basis of research carried out in Polish clothing companies, presented the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the functioning of supply chains (disruptions, ad hoc actions and possible changes in the strategies of these chains, and then the impact of strategic changes in supply chains on sustainable development).

The conducted research shows that the pandemic resulted in disruptions in the entire supply chains, both in the part of the chains related to distribution and sales, as well as production and supply.

Pandemic-induced changes and disruptions in clothing distribution are as follows:

As a result of the lock-down, many companies experienced a decrease in sales in traditional stores, especially those located in shopping malls, while there was a sharp increase in sales online.

Periodically, an increase in stocks in distribution centers and in warehouses of finished products was observed, caused on the one hand by a lock-down in stationary stores, and on the other—by deliveries of previously ordered new products, e.g., from countries with low production costs.

Some deliveries of sewn garments from low-cost countries have been delayed, and transportation costs have increased significantly due to increased freight prices.

Pandemic-induced changes and disruptions in clothing production are as follows:

Sewing plants in Poland producing for orders and according to designs of other companies, experienced a significant decrease in production orders, especially from foreign contractors. These sewing factories were usually looking for other contractors, e.g., in Poland.

Disruptions have occurred in some sewing factories due to high absenteeism; therefore, some Polish clothing companies were looking for subcontractors in Poland or in the Eastern Europe (e.g., Belarus, Ukraine).

Pandemic-induced changes and disruptions in the supply of clothing companies are as follows:

Periodically, there were shortages of some supply goods, e.g., materials and packaging.

Sometimes there were delays in delivery, especially from low cost countries.

There has been a significant increase in the prices of some supply goods and a significant increase in the prices of maritime transport.

The companies, fearing supply disruptions and further price increases, created larger supply stocks.

Two types of responses to disturbance caused by the pandemic have been observed:

Initial, short-term reaction—ad hoc actions eliminating or reducing the negative effects of disturbances,

Assuming that the disruptions or changes caused by the pandemic will persist even after the end of the pandemic—long-term changes in elements of the logistics strategy.

Initially, companies tried to respond to disruptions ad hoc, e.g.,:

in the case of disruptions at customers, suppliers or subcontractors—looking for new contractors,

in the case of anticipated supply disruptions and price increases—building stocks,

in the case of an increase in the number of orders from online customers—execute the increased orders using the resources available so far.

So these were short or medium term actions.

On the other hand, if companies recognized that the changes caused by the pandemic will continue even after the end of the pandemic, the companies changed elements of their logistics strategy.

The long-term strategic changes that have occurred or may occur in the future with the pandemic include:

Increasing the share of e-commerce in distribution,

Reallocation of production—return of clothing production to Europe,

Less stable relationships in supply chains.

So the author’s hypothesis has been confirmed: In addition to its short-term effects, the pandemic will also have strategic long-term effects on the supply chains of apparel companies.

These strategic changes will have an impact on sustainable development (on the ecological and social aspects).

In conclusion, in distribution companies, which are supply chain leaders, the e-commerce channel has grown rapidly and will continue to grow as a result of the pandemic. In this group of companies, a possible effect may also be reallocation of production—outsourcing a part of production regionally or locally instead of in low-cost countries.

In Polish manufacturing companies (both leaders and participants in the supply chain), the pandemic may result in greater flexibility of relations of participants of the supply chains. Firms experiencing both supply and demand side disruptions may be able to mitigate risk through a highly flexible supply chain structures.

Comparing the results of the research performed by the author of the article with other research, both similarities and differences can be seen.

Many authors indicate that disruptions in global supply chains were greater than in local ones. The research of the author of this article confirms this, but it also shows that there were less disruptions in supply chains in which the firms are located in one country than in different countries. It is not just about geographic distance. Polish sewing companies strongly experienced the lack of orders from foreign companies, e.g., from Germany, which border Poland (so the geographical distance was small). There were fewer disruptions in relations between Polish companies.

Many authors believe that the pandemic will result in the reallocation of production to Europe. The author’s research shows that part of production of clothing had already returned to Europe before the pandemic. In Europe, however, mainly high-quality clothing is sewn, as well as fashion hits that must very quickly reach customers. According to the author, despite the disruptions and increased costs in global supply chains, a mass return of production to countries such as Poland cannot be expected, because the production of cheap clothes in low-cost countries is still profitable, and there are not enough sewing workers in Poland. However, it is possible to transfer production to countries where labor costs are lower than in Poland, e.g., to Eastern Europe, under the condition of stabilization of political situation in this region.

The authors also pointed to a sharp increase in internet trade. Weber’s study, which concerned e-commerce distribution and the disruptions caused by its rapid growth, confirmed the results of the research of the author of this article, even though they concerned a different areas (South Africa and Poland). Interestingly, this study was conducted using the same method (interviews).

This article enriches the body of knowledge by being one of the first empirical studies to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Poland’s supply chains in the clothing industry. It is also the most comprehensive study:

it applies to all areas of logistics (procurement, production, distribution, transport, storage and stock maintenance),

it presents not only the short-term impact of a pandemic on supply chains, but also the long-term impact and change in the logistics strategies,

it presents not only the impact of the pandemic on the functioning of supply chains, but also on sustainable development,

concentrates on one industry (clothing industry) and in one geographical area (Poland),

the applied research method (interviews) allowed very detailed results to be obtained.

Further research directions in this field, proposed by the author, are as follows:

repeating the interviews after some time (e.g., at the next wave of a pandemic or after the end of the pandemic),

in-depth research using the survey method,

conducting similar research in enterprises in other industries or located in a different geographic area (in another country) and comparison with the research presented in this article.