Selecting Key Resilience Indicators for Indigenous Community Using Fuzzy Delphi Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Resilience

2.2. Classic Theory Foundation of Resilience

3. Resilience Measurement and Indicators

4. Materials and Methods

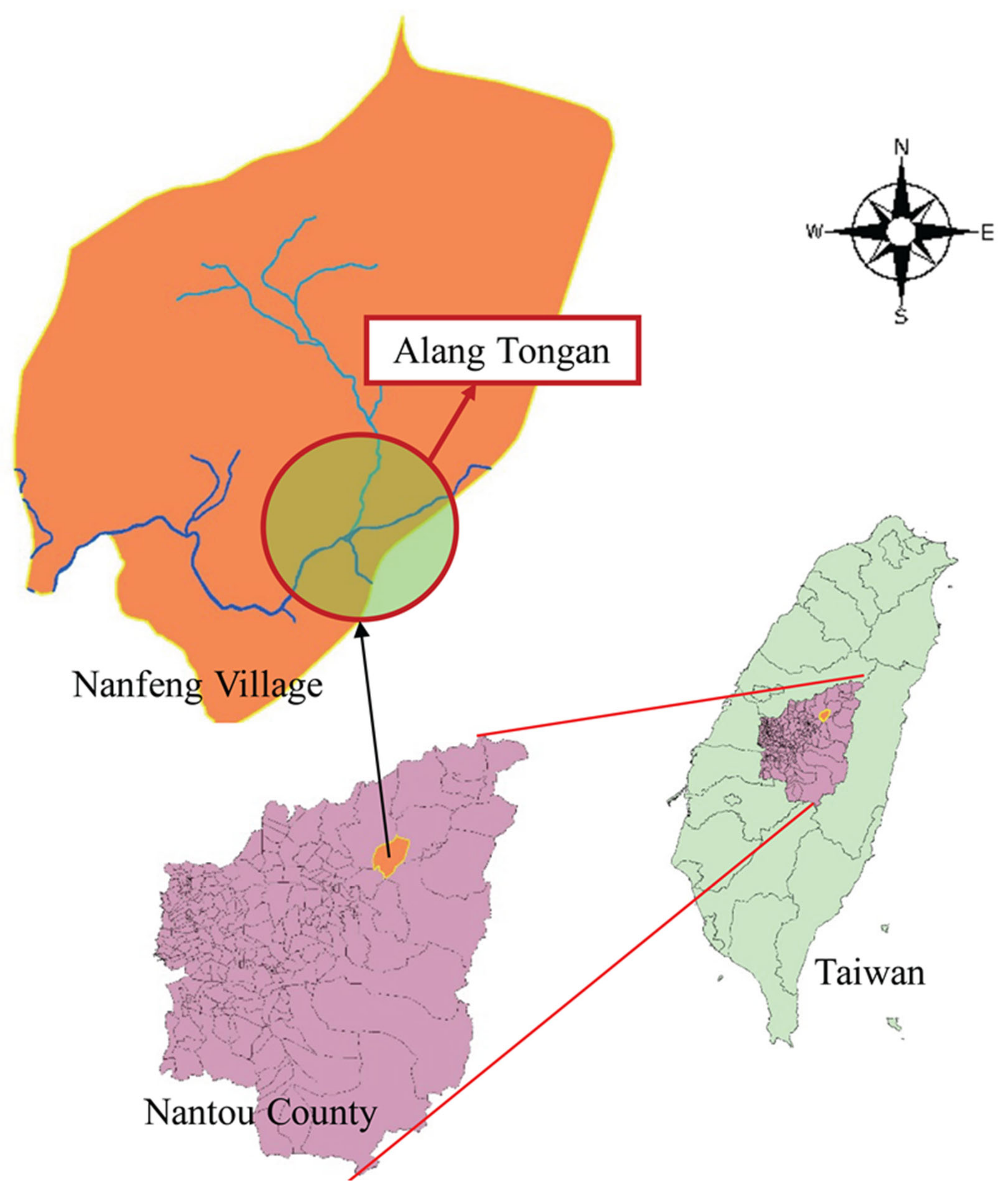

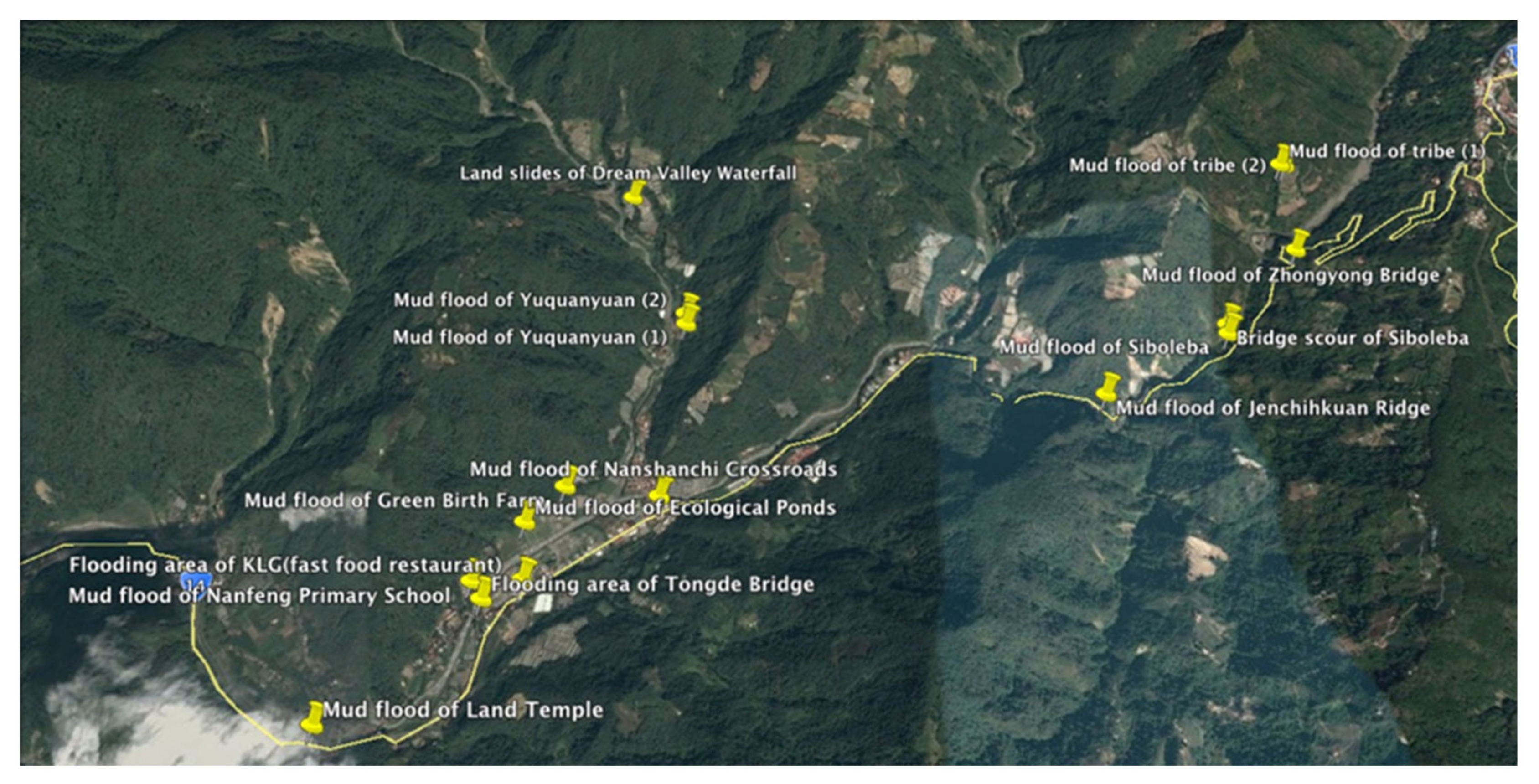

4.1. Research Field

4.2. Indigenous Resilience Index Construction Process

4.3. Resilience Indicator Development through In-Depth Interview

4.4. Sampling Procedures

4.5. Procedures of the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM)

- Step 1:

- When all the evaluation indicators were confirmed, the expert committee was organized immediately to evaluate each indicator’s content. Focusing on the level of importance of the assessment, the value range was specified. The minimum value of this value range indicates the “most conservative cognitive value” by the expert when it comes to the quantified score of the assessed item. On the other hand, the maximum value of the value range represents the “most optimistic cognitive value” as far as the quantified score of the assessed item is concerned.

- Step 2:

- The most conservative and optimistic values were calculated. The extraordinary values outside of the two standard deviations were then deleted, and the fuzzy theory was applied to calculate the minimum value CiL, geometric mean CiM, and maximum value CiU in the conservative value, as well as the minimum value OiL, geometric mean OiM, and maximum value OiU in the optimistic value.

- Step 3:

- The conservative value of the triangular fuzzy number for every assessment item i; Ci = (CiL,CiM,CiU) and the triangular fuzzy number of the “most optimistic cognitive value” were calculated, Oi = (OiL,OiM,OiU) as shown in Figure 3.

- Step 4:

- Next, the experts’ consensus level Gi were calculated in three ways:

- (1)

- If the triangular fuzzy numbers demonstrate no overlapping, as CiU ≤ OiL, it implies that the sentiment intervals of experts show a consensus. If that is the case, the evaluation item i “value importance level that has reached an agreement” Gi, equals the average of CiM and OiM. The calculation Equation (1) was shown as below:

- (2)

- If two triangular fuzzy numbers overlap, then (CiU > OiL) and Zi > Mi, where Zi = CiU − OiL and Mi = OiM − CiM. Furthermore, the gray area of the fuzzy relationship is smaller than the interval between the experts’ evaluation items “optimist cognitive of the geometric mean” and “conservative cognitive of the geometric mean.” Although the sentiment intervals of the experts have no consensus sections, the sentiment of the experts that gave extraordinary values and the sentiments of the other experts did not demonstrate significant disparities, leading to sentiment divergence. In that case, the “value importance that has reached a consensus” of assessment item i is calculated based on the following Equation.

- (3)

- If two triangular fuzzy numbers demonstrate overlapping, then (CiU > OiL) and Zi < Mi, it implies that the gray area with a fuzzy relationship Zi is smaller than the interval range of evaluation items “optimistic cognition of the geometric mean” and “conservative cognition of the geometric mean” (Mi). It implies that the sentiment interval values of the experts had no agreement and that the sentiment of the experts that gave extraordinary values and the sentiments of the other experts showed significant disparities, leading to a divergence of opinion.

- Step 5:

- Finally, the important criteria can be selected if the consensus values Gi are greater than a given threshold value between 6.0 and 7.0 (Kuo & Chen, 2008), the formula of Gi calculation is shown below.

5. Results

- (1)

- Social resilience includes 14 types: “Mutual support and care”, “Diversified community participation”, “Community effectiveness”, “Social, community involvement”, “Social support”, “Social cohesion”, “Educational resources and accessibility”, “Sense of belonging to the tribe”, “Creativity and innovation ability”, “Communication and information”, “Mechanisms to encourage young people to return home”, “External links”, “Ability to reduce obstacles”, and “Ability to accept stimuli”.

- (2)

- Cultural resilience includes four types: “the preservation of cultural resources,” “social and cultural fabric,” “Culture and heritage inheritance ability”, and “maintenance of traditional ancestral training and respect for ancestral norms.”

- (3)

- Economic resilience includes three types: “autonomous economic support system,” “community capital (creation of job opportunity),” and economic income (allocation of resources/power).”

- (4)

- Ecological and environmental resilience includes three types: “ecological resources and space maintenance capacity,” “conservation and maintenance of biodiversity”, and “protection and maintenance of agricultural production.”

- (5)

- Policy-related resilience includes two types: “talent cultivation ability” and “community leadership (leadership and resource allocation capabilities).”

6. Discussion

6.1. Multi-Structure of Indigenous Social Resilience

6.2. Gaya-Centered Indigenous Cultural Resilience

6.3. Indigenous Economic Resilience in the Innovative Economic Model

6.4. Constructing a Sustainable Homeland by Applying Ecological and Environmental Resilience

6.5. Policy-Related Resilience Strengthen the Internal Cohesion

7. Conclusions

Research Limits and Future Research Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pimm, S.L. The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 1984, 307, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Wu, T.-C.; Ni, C.-C.; Ng, P.T. Community tourism resilience: Some applications of the scale, change and resilience (SCR) model. Tour. Resil. 2017, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological resilience—In theory and application. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheppard, V.A.; Williams, P.W. Factors that strengthen tourism resort resilience. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 28, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Ng, P.T.; Ni, C.-C.; Wu, T.-C. Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. The value of natural and social capital in our current full world and in a sustainable and desirable future. In Sustainability Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Haalboom, B.; Natcher, D.C. The Power and Peril of “Vulnerability”: Approaching Community Labels with Caution in Climate Change Research. Arctic 2012, 65, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Mackey, B.; McNulty, S.; Mosseler, A. Forest Resilience, Biodiversity, and Climate Change; Technical Series no. 43; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Dominey-Howes, D.; Kelman, I.; Lloyd, K. The potential for combining indigenous and western knowledge in reducing vulnerability to environmental hazards in small island developing states. Environ. Hazards 2007, 7, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J. The applicability of the concept of resilience to social systems: Some sources of optimism and nagging doubts. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftcioglu, G.C. Assessment of the resilience of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes: A case study from Lefke Region of North Cyprus. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Kim, J.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Ash, K. Does tourism matter in measuring community resilience? Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Tsai, H.-M.; Bayrak, M.M.; Lin, Y.-R. Indigenous Resilience to Disasters in Taiwan and Beyond. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H. Faded Color Wings: Oral History of Catching Butterflies in Alang Tongan/Baike. J. Taiwan Indig. Stud. Assoc. 2016, 6, 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B. New developments in emotion regulation with an emphasis on the positive spectrum of human functioning. J. Happiness Stud. 2007, 8, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. The Indigenous Peoples Basic Law. 2018. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0130003 (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A. Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Millar, M.; Johnston, D. Community resilience to volcanic hazard consequences. Nat. Hazards 2001, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganor, M.; Ben-Lavy, Y. Community resilience: Lessons derived from Gilo under fire. J. Jew. Communal Serv. 2003, 79, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, E.; Buckle, P. Developing community resilience as a foundation for effective disaster recovery. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2004, 19, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, A.H. Place, stories, and consequences: Heritage narratives and the control of erosion on Lake County, California, vineyards. Organ. Environ. 2004, 17, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.J.; Reissman, D.B.; Pfefferbaum, R.L.; Klomp, R.W.; Gurwitch, R.H. Building resilience to mass trauma events. In Handbook of Injury and Violence Prevention; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K. Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Wu, T.-C.; Wall, G.; Linliu, S.-C. Perceptions of tourism impacts and community resilience to natural disasters. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musavengane, R.; Kloppers, R. Social capital: An investment towards community resilience in the collaborative natural resources management of community-based tourism schemes. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.S.; Turkington, R. Are invasive species the drivers or passengers of change in degraded ecosystems? Ecology 2005, 86, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. In The Tourism Area Life Cycle; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. Eng. Ecol. Constraints 1996, 31, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.-S.; Gunderson, L.H. (Eds.) Resilience and adaptive cycles. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo, I.; Zurlini, G.; Grato, E.; Zaccarelli, N. Indicating fragility of socio-ecological tourism-based systems. Ecol. Indic. 2006, 6, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: Lessons from resilience thinking. Nat. Hazards 2007, 41, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Turk, E.S. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. In Quality-of-Life Community Indicators for Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, T.S.; Chang, L.Y. Sustainable Community Indicators System-Building of Governance Capacity. Taiwan Found. Democr. 2014, 11, 37–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G.A. Indigenous Science, Climate Change, and Indigenous Community Building: A Framework of Foundational Perspectives for Indigenous Community Resilience and Revitalization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Huang, Y.S. The Establishment of Vulnerability Evaluation Indexes: The Case Study on Shuili Township, Nantou. City Plan 2011, 38, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Glavac, S.; Hastings, P.; Marshall, G.; McGregor, J.; McNeill, J.; Morley, P.; Reeve, I.; Stayner, R. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalili, S.; Harre, M.; Morley, P. A temporal framework of social resilience indicators of communities to flood, case studies: Wagga wagga and Kempsey, NSW, Australia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 13, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Indigenous Peoples. Seediq. Available online: https://www.cip.gov.tw/en/tribe/grid-list/2880927AC24CBF01D0636733C6861689/info.html?cumid=B54B5C7E1E0F994092EDA9D0B7048931 (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Yeh, J.H.-Y.; Lin, S.-C.; Lai, S.-C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yi-Fong, C.; Lee, Y.-T.; Berkes, F. Taiwanese Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Revitalization: Community Practices and Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Chen, Y.-J. Indigenous Knowledge and Endogenous Actions for Building Tribal Resilience after Typhoon Soudelor in Northern Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. The Delphi technique: Past, present, and future prospects—Introduction to the special issue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, A.J. Fuzzy sets, uncertainty, and information. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1990, 41, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.-Y.; Yu, H.-F.; Yang, T.-H. A study of the key factors contributing to the bullwhip effect in the supply chain of the retail industry. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2013, 30, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Kuo, T.-C.; Shyu, G.-S.; Chen, P.-S. Low carbon supplier selection in the hotel industry. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2658–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, T.J.; Pipino, L.L.; Van Gigch, J.P. A pilot study of fuzzy set modification of Delphi. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1985, 5, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.C. Organizational Supports for Aboriginal Tribes’ Relocating-Reconstruction after 921 Chi-Chi Earthquake; Chang Jung Christian University: Tainan, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, A.; Lo, E.; Chen, Y. Incentives crowding out effect and the agricultural development of indigenous community: A case study in Quri Community, Jianshih Township, Hsinchu County, Taiwan. J. Geogr. Sci. 2012, 65, 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M.; Dadd, U.L. Deep-colonising narratives and emotional labour: Indigenous tourism in a deeply-colonised place. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.B. Land rights and deep colonising: The erasure of women. Aborig. Law Bull. 1996, 3, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffie, N.A.M.; Shukor, N.M.; Rasmani, K.A. Fuzzy delphi method: Issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Sciences (LISS), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Horng, J.S.; Lin, L. Training needs assessment in a hotel using 360 degree feedback to develop competency-based training programs. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2013, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-H.; Guo, Y.-J. Developing similarity based IPA under intuitionistic fuzzy sets to assess leisure bikeways. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Concept of Community Resilience | Source |

|---|---|

| Have the ability to rebound and the effective use of materials and economic resources to recover after encountering disaster | Paton, Millar, and Johnston (2001) [23] |

| The ability of individuals and communities to deal with continuous long-term stress; the ability to find undiscovered intrinsic advantages and resources to respond effectively. | Ganor and Ben-Lavy (2003) [24] |

| Resilience is the community’s ability, skills, and knowledge to enable the community to participate fully in disaster recovery and reconstruction | Coles and Buckle (2004) [25] |

| Social politics, social culture, and psychological resources that can promote the safety of residents and ease adversity | Alkon (2004) [26] |

| The ability of community members to take meaningful and deliberate collective action to correct the impact of the problem, including the ability to interpret the environment, intervene and continue to move forward | Pfefferbaum, Reissman, Pfefferbaum, Klomp, and Gurwitch (2007) [27] |

| The existence, development, and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, and surprise. | Magis (2010, p.401) [28] |

| Refers to a wide variety of things, including the social, economic, political, and environmental attributes that influence the prospects for sustainability. Resident communities can use the perspective that it offers to evaluate their situations in tourism development. | Tsai, Wu, Geoffrey, and Linliu (2016) [29] |

| Community resilience identifies the ability of a community to survive a disturbance. It is a bounce-back from various shocks associated with poor devolution, poor funding, and a lack of power-sharing. | Musavengane and Kloppers (2020) [30] |

| Assessment Indicators | Assessment Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Society | A1. Mutual support and care (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) A2. Diversified community participation (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) A3. Community effectiveness (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A4. Social, community involvement (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A5. Social support (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A6. Social cohesion (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006 [37]; Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A7. Educational resources & accessibility (Ciftcioglu, 2017 [14]) A8. Sense of belonging to the tribe (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A9. Creativity and innovation ability (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A10. Communication and information (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) A11. Mechanisms to encourage youth to return home (Lew et al., 2016 [7]) A12. External links A13. Indigenous traits A14. The ability to remove obstacles A15. The ability to accept stimuli | C. Economic | C1. Autonomous economic support system (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) C2. Community capital (Creation of Job Opportunity) (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006 [37]) C3. Economic income (distribution of resources/power) (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006 [37]; Ciftcioglu, 2017 [14]; Wu & Huang, 2011 [40]) C4. Over-reliance on external economic support (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) |

| D. Ecological and Environment | D1. Natural disaster recovery capacity (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) D2. Ecological resources and space maintenance capacity (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) D3. Growth management capability (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) D4. Conservation and maintenance of biological diversity (Ciftcioglu, 2017 [14]) D5. Protection and maintenance of agricultural production (Ciftcioglu, 2017 [14]) | ||

| B. Cultural | B1. The preservation of cultural resources (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) B2. Society cultural fabric (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006 [37]) B3. Local culture and history inheritance capability (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) B4. Maintain the traditional ancestral teachings and respect for ancestral norms | E. Policy | E1. Talent cultivation ability (Chiang & Chang, 2014 [38]) E2. Local political participation (election) (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006 [37]) E3. Community leadership (Leadership and resource allocation capabilities) (Khalili et al., 2015 [42]) |

| Social Aspects of the Indicators Items | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Items | Zi | Mi | Mi − Zi | Gi |

| A1.1 Mutual care amongst organizations and groups | 1 | 4.71 | 3.71 | 6.47 |

| A1.2 Social space for continuation of traditional culture | 2 | 4.46 | 2.46 | 6.15 |

| A2.1 Integration of internal mechanisms of various organizations and groups | 0 | 4.18 | 4.18 | 6.00 |

| A2.2 Organizational ability for continuation of traditional culture | 3 | 3.79 | 0.79 | 6.61 |

| A3.1 Tribes people’s affirmation of the tribe and personal work abilities | 1 | 4.34 | 3.34 | 6.47 |

| A3.2 The ability to restore the traditional tribal lifestyle | 1 | 4.15 | 3.15 | 6.39 |

| A4.1 The extent to which tribes people participate in diverse activities | 2 | 3.80 | 1.80 | 6.71 |

| A4.2 The extent to which tribes people participate in tribal affairs related to society development | 3 | 3.34 | 0.34 | 7.19 |

| A5.1 The extent to which tribes people support the Indigenous community development | 1 | 3.81 | 2.81 | 6.66 |

| A5.2 Feedback mechanism to the tribe or the tribe’s people | 3 | 3.43 | 0.43 | 5.78 |

| A6.1 Autonomous mutual aid mechanism during tribal emergency situation/disaster | 1 | 3.51 | 2.51 | 7.46 |

| A6.2 Mitigation mechanism for when the tribes face a division of opinions. | 1 | 3.65 | 2.65 | 6.57 |

| A7.1 Whether there is sufficient educational resources and facilities within the tribe. | 1 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 6.44 |

| A7.2 Whether there is a program to teach traditional culture lessons | 2 | 4.20 | 2.20 | 6.06 |

| A8.1 The degree of understanding of “Gaya” by the tribe’s people | 1 | 3.52 | 2.52 | 7.48 |

| A8.2 The degree of understanding of traditional culture by the tribe’s people | 1 | 3.65 | 2.65 | 6.67 |

| A8.3 The degree of the tribe’s people mastery of the tribal language | 1 | 3.79 | 2.79 | 6.50 |

| A8.4 The tribe’s people have a strong sense of self-recognition for the Seediq | 1 | 3.52 | 2.52 | 7.51 |

| A9.1 Tribal leaders have the ability to create and innovate | 0 | 4.12 | 4.12 | 7.00 |

| A9.2 Capabilities of vision construction and consolidation | 0 | 4.19 | 4.19 | 7.00 |

| A10.1 Whether the tribe has an open and transparent information platform | 1 | 3.82 | 2.82 | 6.47 |

| A10.2 Whether the tribe’s people understand and trust the use of internal and external resources or subsidies | 2 | 3.82 | 1.82 | 6.76 |

| A11.1 Whether the tribe provides the opportunity for young generation to learn and be hired | 1 | 4.03 | 3.03 | 7.42 |

| A11.2 Whether the tribe has like-minded young people working together for the vision | 1 | 3.63 | 2.63 | 7.39 |

| A12.1 Whether the tribe has the support of external experts or consultants in the process of Indigenous community development | 0 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 7.00 |

| A12.2 Whether the tribe has the support of other external groups, organizations in the process of Indigenous community development | 0 | 3.93 | 3.93 | 7.00 |

| A13.1 Feeling of optimism and contentment with the present condition | 4 | 3.07 | −0.93 | 3.78 |

| A13.2 Natural characteristics of being down-to-earth and hard-working | 7 | 3.29 | −3.71 | 4.82 |

| A13.3 Sense of humor of the Indigenous people | 6 | 3.08 | −2.92 | 4.50 |

| A14.1 Whether the tribe has groups and organizations that can promote Indigenous community development and resolve tribal disputes | 2 | 3.93 | 1.93 | 6.92 |

| A14.2 The ability of the tribe to reconcile different subgroups | 2 | 4.10 | 2.10 | 6.89 |

| A15.1 Whether the tribe has an open mind for acceptance of external stimuli | 1 | 3.89 | 2.89 | 6.49 |

| A15.2 Whether the tribe can accept external stimuli, enabling the tribe to turn around and grow | 1 | 3.86 | 2.86 | 6.50 |

| Indicator Items for Cultural Aspects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Items | Zi | Mi | Mi − Zi | Gi |

| B1.1 Maintain and restore the traditional image of the tribe | 1 | 4.03 | 3.03 | 6.55 |

| B1.2 The mechanism for inheriting traditional wisdom | 1 | 4.03 | 3.03 | 7.41 |

| B2.1 The tribe’s insistence on preserving the integrity of the traditional culture | 1 | 3.84 | 2.84 | 7.35 |

| B3.1 The mechanism of the tribe for maintaining traditional worship ceremonies, hunting, weaving, mother tongue, and other cultures | 2 | 3.99 | 1.99 | 7.03 |

| B3.2 Whether internally there is an ability to investigate and record the collection and construction of local traditional cultural history | 2 | 4.03 | 2.03 | 6.82 |

| B4.1 Whether the tribe’s people can maintain traditional ancestral teachings and respect ancestral norms | 1 | 3.33 | 2.33 | 6.56 |

| Indicator Items for Economic Aspect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Items | Zi | Mi | Mi − Zi | Gi |

| C1.1 Whether the tribe has an independent economic support system, such as: Credit Union, etc. | 1 | 3.83 | 2.83 | 6.58 |

| C2.1 Whether the tribe has a self-sufficient industry | 0 | 3.74 | 3.74 | 7.00 |

| C2.2 Whether the tribe’s people have the possibility of employment | 2 | 3.68 | 1.68 | 8.53 |

| C3.1 Stability of economic income of people in the tribe | 2 | 4.03 | 2.03 | 6.22 |

| C4.1 When facing an emergency situation/disaster, the tribe’s excessive dependence on subsidies and external resources | 2 | 3.80 | 1.80 | 5.86 |

| Indicator Items for Environmental Aspects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Items | Zi | Mi | Mi − Zi | Gi |

| D1.1 The fostering of tribal awareness regarding disaster relief | 1 | 3.84 | 2.84 | 5.66 |

| D1.2 The capability of the tribe regarding an overall disaster relief plan | 1 | 3.72 | 2.72 | 5.68 |

| D1.3 Resilience ability for construction and facilities’ recovery during emergency situations/disasters | 0 | 4.15 | 4.15 | 6.00 |

| D2.1 The tribe’s people possess ecological resources and ability to create space for themselves | 2 | 4.51 | 2.51 | 6.82 |

| D3.1 The mechanism to avoid the tribal land resources being used for improper development | 5 | 4.06 | −0.94 | 5.76 |

| D4.1 Whether the tribe has a mechanism for the conservation and maintenance of biological diversity | 2 | 3.65 | 1.65 | 6.21 |

| D5.1 Whether the tribe has the ability to introspect conventional farming | 2 | 4.32 | 2.32 | 6.84 |

| D5.2 The ability to preserve traditional ethnic plantation and crops | 1 | 3.68 | 2.68 | 7.41 |

| Indicator Items for Environmental Aspect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Items | Zi | Mi | Mi − Zi | Gi |

| E1.1 The mechanism for tribal talent training | 3 | 3.63 | 0.63 | 6.61 |

| E2.1 The extent to which tribes people participate in local politics | 6 | 2.98 | −3.02 | 5.03 |

| E2.2 The extent of participation of local politics in affecting Indigenous community development | 6 | 2.97 | −3.03 | 5.07 |

| E3.1 Whether the tribal leaders have the ability to integrate the various subgroups and organize groups | 2 | 3.52 | 1.52 | 6.15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tseng, Y.-P.; Huang, Y.-C.; Li, M.-S.; Jiang, Y.-Z. Selecting Key Resilience Indicators for Indigenous Community Using Fuzzy Delphi Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042018

Tseng Y-P, Huang Y-C, Li M-S, Jiang Y-Z. Selecting Key Resilience Indicators for Indigenous Community Using Fuzzy Delphi Method. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042018

Chicago/Turabian StyleTseng, Yung-Ping, Yu-Chin Huang, Mei-Syuan Li, and You-Zih Jiang. 2022. "Selecting Key Resilience Indicators for Indigenous Community Using Fuzzy Delphi Method" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042018

APA StyleTseng, Y.-P., Huang, Y.-C., Li, M.-S., & Jiang, Y.-Z. (2022). Selecting Key Resilience Indicators for Indigenous Community Using Fuzzy Delphi Method. Sustainability, 14(4), 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042018