Assessment of Disused Public Buildings: Strategies and Tools for Reuse of Healthcare Structures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. State-of-the-Art Public Investments

1.2. Strategies for Sustainable Regeneration Intervention: State-of-the-Art Heritage Buildings

1.3. Support for BIM in the Regeneration of Existing Buildings

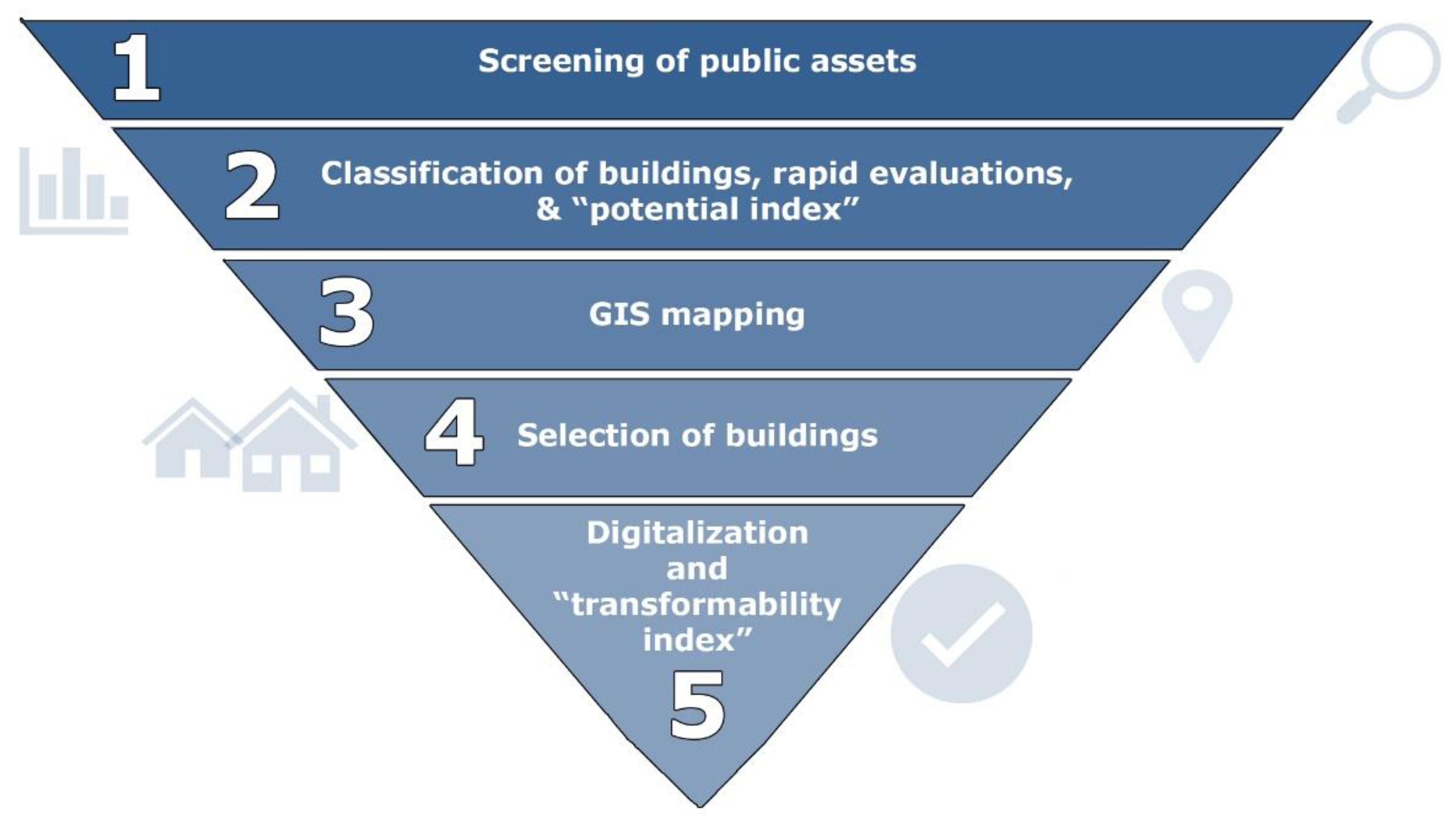

2. Methodology

2.1. Focus on Phase 2: Potential Index

- State of conservation and maintenance, focusing on the following elements: floors; walls and ceilings; fixtures; electrical system; water system and sanitation; heating system; common areas (accesses, stairs, lifts, façades, roofs, and common parts in general). “The state of conservation of the building is considered mediocre if, out of the above-mentioned elements or groups of elements, three are in poor condition […], poor if four of them are in poor condition […] or if the real estate unit does not have an electrical system or water system with running water in the kitchen and services, or if it does not have private toilets […]” [69] (art. 21of Italian Law 392/78);

- Context; the score is related to the geographical location and depends on the environmental quality, availability of public services, general perception of safety, etc. If the building is located in an industrial area the score is 1, in an agricultural area 2, 3 in the historic center, 4 in a commercial area, and 5 in a residential area;

- Accessibility; the score is related to the difficulty of reaching the building both by public and private transportation. For public transport (which is weighted 70% compared to 30% for private transport), the distances from the bus, metro, and railway stations are considered, and for private vehicles, the types of roads and the presence of nearby parking lots. Scores are determined as a function of the distance r (see Table 2, top left);

- Availability of services: the score is given according to the proximity to basic services (education, culture, health, commercial areas, etc.) and as a function of the distance r (see Table 2, below);

- Percentage of the building currently not in use or the “non-use ratio”, whereby the less the building is unused, the higher the score. This normalization underlines the convenience of transforming an unused building compared to one partially in use. Scores are defined as a function of the disused area (DA) compared to the total gross area of the building (see Table 2, top right).

2.2. Focus on Phase 5: Slight Reuse and Transformability Index

2.2.1. Indicators, Normalization, and Weighting

- The usability indicator measures the quantitative relationship between distribution space and served spaces (rooms) [75,80]. Numerically, it is the ratio between the total rooms-served area (excluding corridors/hallways) and net area (rooms + distribution) (1). The surfaces calculation is the net of internal partitions and walls and external spaces. Regarding layout reconfiguration, for healthcare facilities’ reuse, on the contrary to housing reconfiguration [79], the lower the usability indicator is, the lower the chances are of transformation. This is because when distribution spaces are large, there is little room space for the required functions.The usability indicator value is normalized to an increasing appreciation curve with concavity pointing upward [19,20]. The higher boundary is at 90% and the lower at 50% assuming that for an area with low usability, connective spaces have a huge impact, meaning less freedom to reorganize the space. In Table 3, single boundaries are shown.

- Next, the fragmentation indicator relates the external and internal borders to the total area available [75], providing information concerning the general layout. Numerically, it is the ratio between the external wall length and internal wall length, with the square of the gross area (2). Contrary to the formula provided in [79], the denominator is calculated as the square of the gross area, to compare buildings of different sizes.The fragmentation value is normalized to a decreasing appreciation curve with concavity pointing downward. The higher the internal fragmentation, the lower the opportunities are for transformability and the higher the cost of layout reorganization. Boundary values have been selected looking at other pieces of research where such indicators were applied [79,81], fine-tuning them according to the particular set of heritage masonry buildings here considered. In Table 4, single boundaries are shown.

- The constructive modifiability indicator relates the changeable areas of the plan to the invariant elements [75,80] and provides information on the structural and construction features of the buildings which strongly affect its transformability. It is the ratio between non-modifiable elements’ total area (in the plan, identified in structural and plant elements) and gross area (3).Normalization produces a decreasing curve with concavity downward, i.e., transformability decreases as the incidence of non-modifiable elements increases. Reinforced concrete (r.c.) structures—especially r.c. frame structures—have a lower incidence of non-modifiable elements compared to masonry structures, and consequently, higher transformability. On the other hand, in masonry buildings, layout reorganization is limited by the walls and by structural constraints. In this paper, only structural and plant elements have been considered as non-modifiable elements, but in future works, to also evaluate artistic/architectural conservation issues, the calculation may include vaulted ceilings, walls with frescos, and fine floorings. Here, boundary values have been fine-tuned according to the set of heritage masonry buildings considered in Section 3. In Table 5, single boundaries are shown.

- The roof implementation indicator provides information concerning the possibility of installing sustainability devices (such as solar or photovoltaic panels, insulation layers, heat pumps, etc.) on roofs. In the present paper, only the potential for installing solar and photovoltaic panels is considered. For sloped roofs, only non-shaded surfaces and those oriented southward (±30°) are considered, while for flat roofs, only non-shaded surfaces (4). The indicator provides information concerning the possible green-energy production after renovation.In this case, normalization produces an ascending proportional line. The value of 50% has been selected as the lower boundary while 100% is the higher one. In Table 6, single boundaries are shown.

- The external envelope wall implementation indicator is one of the two indicators related to façades. It provides information concerning the possibility of intervening with the external envelope walls to add further cladding or insulation panels. It is the ratio between surfaces without any kind of constraint—artistic/architectural or structural—and the whole façade surface (5). The indicator is strictly related to heritage conservation issues and any kind of constraint is considered.For the roof implementation indicator, normalization produces an increasing proportional line. The value of 0% has been selected as the lower boundary while 100% is the higher one. In Table 7, single boundaries are shown.

- The window-to-wall ratio, or WWR, provides information on the incidence of the transparent envelope in relation to the total vertical envelope surface [82], thus measuring the impact of the façade structure on energy consumption and internal comfort conditions. A high WWR affects solar gains and daylight in winter and may lead to overheating in summer [83]. In hot regions, optimal WWR values should not exceed 10%, or 20% in a moderate climate and 35–45% in central Europe. In retrofitting listed buildings, due to constraints in adding insulation to the external envelope, often, the only open chance is to operate on the windows. Buildings with a high WWR may provide the opportunity to achieve easy but effective results in energy consumption reduction by changing or restoring ancient single-glazed windows. Previous studies showed [84,85] that the replacement of windows in badly insulated exterior walls (U-value bigger than 1.00 W/m2K) has a significant impact on energy savings for high-WWR buildings. The WWR formula is (6):The normalization produces an ascending proportional line. The value of 5% has been selected as the lower boundary while 35% is the higher one. In Table 8, single boundaries are shown.

2.3. Automatic Calculation of BIM Using a Plug-In

- Usability indicator calculation: select served areas in floor plans and net areas;

- Fragmentation indicator calculation: select both external and internal walls in the plan and gross areas. The values of the lengths of individual external and internal walls are automatically retrieved;

- Constructive modifiability indicator calculation: select both non-modifiable element areas (identified in the plan as structural and plant elements) and gross areas;

- Roof implementation indicator calculation: select areas in which it is possible to install solar and photovoltaic panels, included in the roof plan and total roof area;

- External envelope wall implementation indicator calculation: select (in elevation view) surfaces with and without any kind of constraint (artistic/architectural or structural elements);

- Window-to-wall ratio indicator calculation: select (in elevation view) all windows included in the analyzed façade and walls in which the windows are contained.

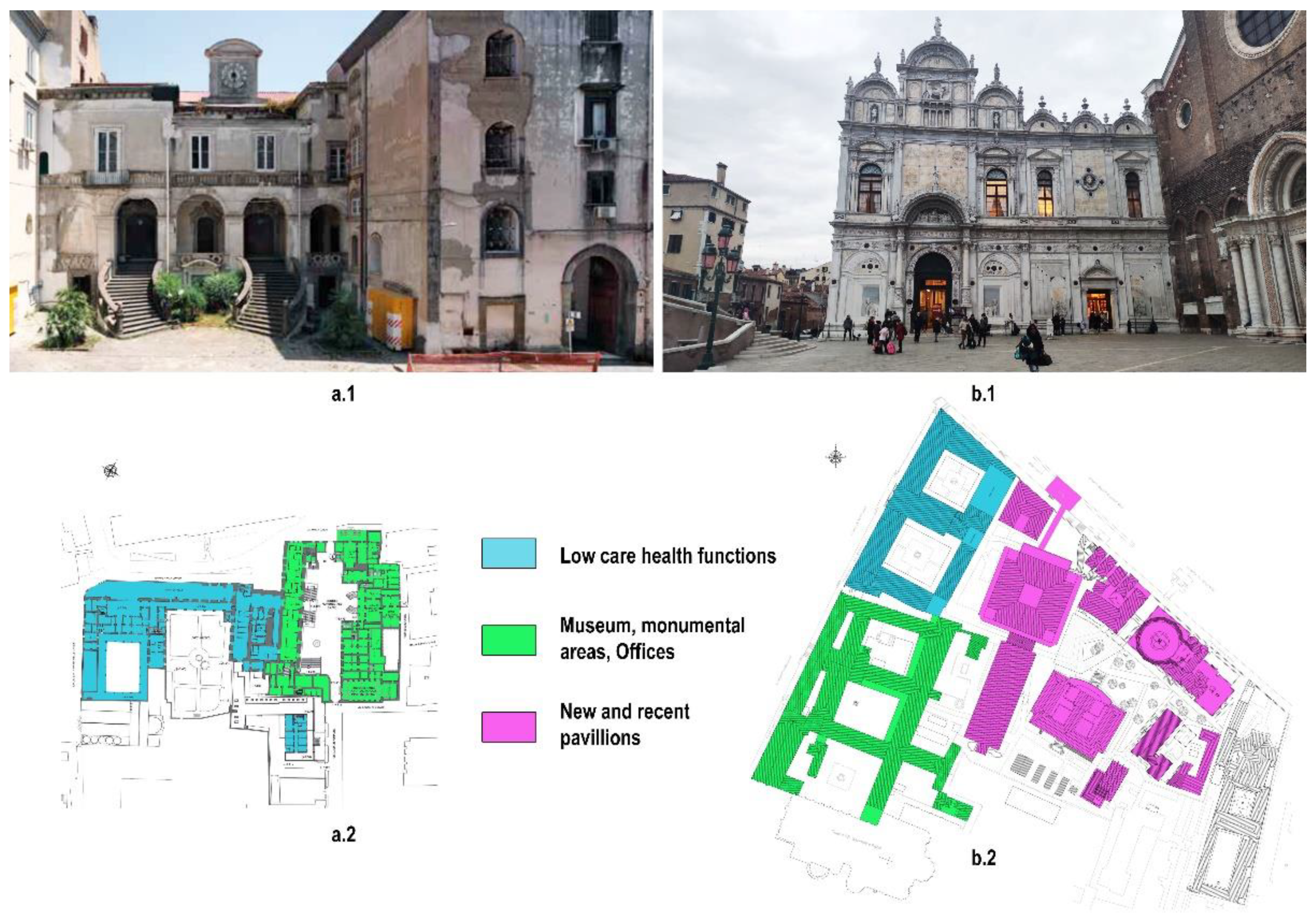

3. Case Study

3.1. Campania’s Public Stock of Disused Buildings

3.2. Reuse Strategies for the Selected Monumental Healthcare Structures

3.3. Gesù e Maria Monumental Hospital

4. Discussion

4.1. Application of the Tool

4.2. Main Findings

- the transformability index is clearly influenced by the type of load-bearing structure and materials employed. For example, the CM indicator provides trivial results when the masonry and r.c. frame structures are compared. The comparison of scores is useful for large-scale analysis when buildings with different features are considered. If only listed buildings are compared—usually masonry structures—the CM indicator provides useful information concerning the internal layout and propensity to undergo transformation;

- within the set of three buildings analyzed, GEM proved to be the more transformable (score 2.8). This is due mainly to its big open spaces on the first floor, created during a 19th-century transformation. ANN proves to be the less transformable building (score 2.15), especially given the artistic and architectural constraints of its roof and façades;

- when, at an early stage, specific objectives for reuse are defined (e.g., energy transformation or layout reconfiguration), the indicators can be weighed to take a different significance. If the transformation is just in terms of energy retrofitting, the RI, EEI, and WI indicators may weigh 0.75 (0.25 each) and the other three indicators (U, F, and CM) 0.25 (0.083 each), leading to different results. In this case, in GEM the score remains the same (transformability index equal to 2.81), for SGN, it increases up to 2.65, while for ANN, it decreases to 1.72. For layout reconfiguration, indicators may be weighed the other way round: the U, F, and CM indicators may weigh 0.75 (0.25 each) and RI, EEI, and WI 0.25 (0.083 each). Again, for GEM, the score does not change (transformability index equal to 2.80). For SGN, it decreases to 1.92, and for ANN, it increases up to 2.58. The weighing process related to early-stage targets may change the priorities of intervention;

- non-listed buildings are more transformable when compared with listed buildings. This depends on structural characteristics (often listed buildings have a masonry load-bearing structure while non-listed buildings have a r.c. frame) and limitations due to the presence of constraints (artistically/architecturally valuable elements) on external walls that hinder the addition of new insulation or cladding layers. High values of transformability indexes for non-listed buildings are balanced by low scores for potential indexes, due mainly to peripheral locations.

5. Conclusions

- for all buildings, a “potential index” related to contextual evaluations and specific building features can be defined relying on five indicators relating to the presence of services in the surroundings, accessibility, environmental and architectural quality of the context, building conservation, and size of the disused area;

- based on specific targets defined by public administrations, buildings can be selected for further investigations and digitization processes. For selected buildings, the transformability is quantitatively computed by means of six indicators: the usability, fragmentation, construction modifiability, roof implementation, external envelope wall implementation, and window-to-wall ratio. These indicators allow evaluations of aspects related to historical and cultural values, which is meaningful given that the target is mainly listed buildings. The combination of these six indicators defines a “transformability index” that allows us to compare several buildings;

- particular attention is paid to the evaluation of the propensity of a building to be transformed, introducing an index of transformability. It can be computed automatically owing to a plug-in for Revit developed to allow fast assessments, which are particularly useful when many buildings must be managed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- MEF. Patrimonio della PA. Rapporto Annuale Rapporto Sui Beni Immobili delle Amministrazioni Pubbliche; Dipartimento del Tesoro: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Dettori, M.; Raffo, M.; Appolloni, L. Housing problems in a changing society: Regulation and training needs in Italy. Ann. di Ig. 2020, 32, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Parliament. Law n. 373/1976-Norme per il Contenimento del Consumo Energetico per usi Termici Negli Edifici; Gazzetta Ufficiale: Rome, Italy, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Parliament. Law n. 64/1974-Provvedimenti per le Costruzioni Con Particolari Prescrizioni per le Zone Sismiche; Gazzetta Ufficiale: Rome, Italy, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, L.; Polverino, F. Rifunzionalizzazione del patrimonio culturale pubblico: Il caso degli ospedali storici. In New Horizons for Sustainable Architecture Nuovi Orizzonti per L’architettura Sostenibile; Cascone, S.M., Margani, G., Sapienza, V., Eds.; EdicomEdizioni: Gorizia, Italy, 2020; pp. 634–652. ISBN 9788896386941. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, L.; Marmo, R.; Polverino, F. Gli ospedali storici: Salute e patrimonio per la rigenerazione urbana. Urban. Inf. 2020, 04, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Ministers. Recovery and Resilience Plan. #NextGenerationItalia; Gazzetta Ufficiale: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, A.; Avagnina, M.; Cardinale, G.; D’Alessandro, M.; Eramo, B.; Mangia, M.G.; Martino, S.; Mazzola, M.R.; Prezioso, M.; Rosa, P. Linee Guida per la Redazione del Progetto di Fattibilità Tecnica ed Economica da Porre a Base Dell’affidamento di Contratti Pubblici di Lavori del PNRR e del PNC; Ministero delle Infrastrutture e della Mobilità Sostenibili: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acampa, G.; Giuffrida, S.; Napoli, G. Appraisals in Italy. Identity, contents, prospects. Valori e Valutazioni 2018, 20, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bolici, R.; Leali, G. Valorizzazione del patrimonio immobiliare dismesso o sottoutilizzato. Progettare per il coworking. In Abitare insieme. Abitare il futuro (Living together. Inhabiting the Future); Gerundio, R., Fasolino, I., Eds.; Clean Edizioni: Napoli, Italy, 2015; pp. 1360–1369. ISBN 9788884975447. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, C. Rigenerare per valorizzare. La rigenerazione urbana “gentile” e la riduzione delle diseguaglianze. Aedon 2021, 2, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, F.; Della Spina, L. Circular Economy and Resilient Thought: Challenges and Opportunities for Regeneration of Historical Urban Landscape. LaborEst 2021, 22, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Assembly, U.N. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/hk/en/what-we-do/2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIkZ2n4Z2I9gIVxbWWCh3KwQojEAAYASAAEgL4tvD_BwE (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bernardoni, A.; Cossignani, M.; Papi, D.; Picciotti, A. Il ruolo delle imprese sociali e delle organizzazioni del terzo settore nei processi di rigenerazione urbana. Indagine empirica sulle esperienze italiane e indicazioni di policy. Impresa Soc. 2021, 3, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Preiser, W.F.E. Building performance assessment—From POE to BPE, A personal perspective. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2005, 48, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampa, G.; Grasso, M. Heritage evaluation: Restoration plan through HBIM and MCDA. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 949, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, H. Integrated Plan Analysis (IPA) of Buildings. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress “Construction for Development”, Cape Town, South Africa, 14–17 May 2007; pp. 686–698. [Google Scholar]

- van der Voordt, T. Quality of design and usability: A vitruvian twin. Ambient. Construido 2009, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fattinnanzi, E. La valutazione della qualità e dei costi nei progetti residenziali. Il brevetto SISCo-Prima Parte. Valori e Valutazioni 2011, 7, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fattinnanzi, E. La valutazione della qualità e dei costi nei progetti residenziali. Il brevetto SISCo-Seconda Parte. Valori e Valutazioni 2012, 8, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bluyssen, P.M. EPIQR and IEQ: Indoor environment quality in European apartment buildings. Energy Build. 2000, 31, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.; Dascalaki, E.; Droutsa, P.; Kontoyiannidis, S. EPIQR–TOBUS–XENIOS–INVESTIMMO, European Methodologies & Software Tools for Building Refurbishment, Assessment of Energy Savings and IEQ. In Proceedings of the 33rd International HVAC Congress, Belgrade, Serbia, 4–6 December 2002; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen, A. InterSAVE. International Survey of Architectural Values in the Environment; Ministry of Environment and Energy, the National Forest and Nature Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1997; ISBN 87-601-5194-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, T. Intersave–International Survey of Architectural Values in the environment. In Improving the Quality of Suburban Building Stock. CO ST Action TU0701; Di Giulio, R., Ed.; UniFe Press: Ferrara, Italy, 2012; pp. 303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Dziembowska-Kowalska, J.; Funck, R.H. Cultural activities as a location factor in European competition between regions: Concepts and some evidence. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2000, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedate, A.; Herrero, L.C.; Sanz, J.Á. Economic valuation of the cultural heritage: Application to four case studies in Spain. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholt, K. Economic impacts of cultural heritage-Research and perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampa, G.; Parisi, C.M. Management of Maintenance Costs in Cultural Heritage. In Appraisal and Valuation. Contemporary Issues and New Frontiers; Morano, P., Oppio, A., Rosato, P., Sdino, L., Tajani, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 195–212. ISBN 978-3-030-49579-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; Muñoz-González, C.; Joyanes-Díaz, M.D.; Jiménez-Morales, E.; López-Osorio, J.M.; Barrios-Pérez, R.; Rosa-Jiménez, C. Heritage risk index: A multi-criteria decision-making tool to prioritize municipal historic preservation projects. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Decree 22/01/2004, n. 42. Codice Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, ai sensi dell’articolo 10 Legge 6 luglio 2002, n. 137; Italy. 2004. Available online: https://web.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/04042dl.htm (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Konsta, A. Built heritage use and compatibility evaluation methods: Towards effective decision making. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2019, 191, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conejos, S. Designing for Future Building Adaptive Reuse. Ph.D. Thesis, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia, 12 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rypkema, D.; Wiehagen, K. Dollars and Sense of Historic Preservation. The Economic Benefits of Preserving Philadelphia’s Past; Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elsorady, D.A. Assessment of the compatibility of new uses for heritage buildings: The example of Alexandria National Museum, Alexandria, Egypt. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantacuzino, S. Re-Architecture: Old Building-New Uses; Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-0500341087. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0679741954. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, D.F.; Zimnicki, K. Integrating Sustainable Design Principles into the Adaptive Reuse of Historical Properties Construction Engineering; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shooshtarian, S.; Maqsood, T.; Caldera, S.; Ryley, T. Transformation towards a circular economy in the Australian construction and demolition waste management system. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtarian, S.; Caldera, S.; Maqsood, T.; Ryley, T. Using recycled construction and demolition waste products: A review of stakeholders’ perceptions, decisions, and motivations. Recycling 2020, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Zeng, Z.T. A multi-objective decision-making process for reuse selection of historic buildings. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, C.; Wong, F.K.W.; Hui, E.C.M.; Shen, L.Y. Strategic assessment of building adaptive reuse opportunities in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Smith, J. Improving the implementation of adaptive reuse strategies for historic buildings. In Proceedings of the Le vie dei Mercanti S.A.V.E.HERITAGE: Safeguard of Architectural, Visual, Environmental Heritage, Naples, Italy, 9–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Shuai, C.; Wang, T. Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for the Adaptive Reuse of Industrial Buildings in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farjami, E.; Türker, Ö.O. The extraction of prerequisite criteria for environmentally certified adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Matot, R.; Costa, A.; Tavares, A.; Fonseca, J.; Alves, A. Conservation Level Assessment Application to a heritage building. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 279, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piana, M. Problemi d’integrazione con le preesistenze. In Restauro Architettonico e Impianti; Carbonara, G., Ed.; UTET: Torino, Italy, 2001; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ragni, M.; Maurano, A.; Scoppola, F.; Soragni, U.; Baraldi, M.; D’amico, S.; Mercalli, M.; Banchini, R.; Belisario, M.G.; Rubino, C.; et al. Linee di Indirizzo per il Miglioramento Dell’efficienza Energetica nel Patrimonio Culturale. Architettura, Centri e Nuclei Storici ed Urbani; Ministero della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- Crova, C. Le linee guida di indirizzo per il miglioramento dell’efficienza energetica nel patrimonio culturale. Architettura, centri e nuclei storici ed urbani: Un aggiornamento della scienza del restauro. In Proceedings of the XXXIII Convegno Internazionale di Scienza e Beni Culturali “Le nuove frontiere del restauro. Trasferimenti, contaminazioni, ibridazioni”, Bressanone, Italy, 27–30 June 2017; Edizioni Arcadia Ricerche. pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fanou, S.; Poggi, M. Recupero sostenibile ed energeticamente consapevole dell’edilizia storica e monumentale. In La basilica di San Paolo Maggiore a Bologna e il Palazzo Regis a Roma. Restauro e Nuove Tecniche; Diamanti, M., Benvenuti, S., Dal Mas, R., Eds.; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2016; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, A.; Hansen, E.J.d.P.; Rieser, A.; Giancola, E.; Pracchi, V.N.; Mauri, S.; Marincioni, V.; Gori, V.; Fouseki, K.; López, C.S.P.; et al. Conservation-compatible retrofit solutions in historic buildings: An integrated approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendations PCM. Assessment and Mitigation of Seismic Risk of Cultural Heritage with Reference to the Italian Building Code (NTC2008). (in Italian); G.U. no. 47, 26/02/2011 (suppl. ord. no. 54); 2011; Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=-ypqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1190&lpg=PA1190&dq=Assessment+and+Mitigation+of+Seismic+Risk+of+Cultural+Heritage+with+reference+to+the+Italian+Building+Code+(NTC2008).+(in+Italian);&source=bl&ots=Te5OHnvMgH&sig=ACfU3U3Bh_dxHja1939fT_lCnoesYsP21w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj3gcKsxoj2AhXDG6YKHc97DEsQ6AF6BAgCEAM#v=onepage&q=Assessment%20and%20Mitigation%20of%20Seismic%20Risk%20of%20Cultural%20Heritage%20with%20reference%20to%20the%20Italian%20Building%20Code%20(NTC2008).%20(in%20Italian)%3B&f=false (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Nassi, L. (Ed.) La Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Culturale e la Sicurezza Antincendio; Ministero dell’Interno: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9788894340716. Available online: http://www.vigilfuoco.it/aspx/download_file.aspx?id=24855 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Gigliarelli, E.; Calcerano, F.; Cessari, L. Heritage Bim, Numerical Simulation and Decision Support Systems: An Integrated Approach for Historical Buildings Retrofit. Energy Procedia 2017, 133, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Acampa, G.; Marino, G.; Tesoriere, G. Cycling Master Plans in Italy: The I-BIM Feasibility Tool for Cost and Safety Assessments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, C.; Murphy, M. Integration of Historic Building Information Modeling (HBIM) and 3D GIS for recording and managing cultural heritage sites. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia, VSMM 2012: Virtual Systems in the Information Society, Milan, Italy, 2–5 September 2012; pp. 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Banfi, F. The evolution of interactivity, immersion and interoperability in HBIM: Digital model uses, VR and AR for built cultural heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocobelli, D.P.; Boehm, J.; Bryan, P.; Still, J.; Grau-Bové, J. BIM for heritage science: A review. Herit. Sci. 2018, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yusoff, S.N.S.; Brahim, J. Implementation of building information modeling (Bim) for social heritage buildings in kuala lumpur. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; McGovern, E.; Pavia, S. HBIM. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 76, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, L.M.; Aly, D.; Tarek, S. Integrating HBIM (Heritage Building Information Modeling) Tools in the Application of Sustainable Retrofitting of Heritage Buildings in Egypt. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 34, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jordan-Palomar, I.; Tzortzopoulos, P.; García-Valldecabres, J.; Pellicer, E. Protocol to manage heritage-building interventions using heritage building information modelling (HBIM). Sustainability 2018, 10, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ismail, E.D.; Said, S.Y.; Jalil, M.K.A.; Ismail, N.A.A. Benefits and Challenges of Heritage Building Information Modelling Application in Malaysia. Environ. Proc. J. 2021, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygi, G.; Agugiaro, G.; Hamamcloǧlu-Turan, M.; Remondino, F. Evaluation of GIS and BIM roles for the information management of historical buildings. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 2, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dore, C.; Murphy, M. Semi-automatic generation of as-built BIM façade geometry from laser and image data. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2014, 19, 20–46. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, A.; Alitany, A.; Boehm, J.; Robson, S. Jeddah Historical Building Information Modelling “JHBIM”–Object Library. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 2, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Ashraf, F. HBIM platform & smart sensing as a tool for monitoring and visualizing energy performance of heritage buildings. Dev. Built Environ. 2021, 8, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilimantou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Nikitakos, I.A.; Ioannidis, C.; Moropoulou, A. GIS and BIM as integrated digital environments for modeling and monitoring of historic buildings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guzzetti, F.; Anyabolu, K.L.N.; Biolo, F.; D’ambrosio, L. BIM for existing construction: A different logic scheme and an alternative semantic to enhance the interoperabilty. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Parliament. Law 392/1978-Disciplina delle Locazioni di Immobili Urbani; Italian Parliament: Rome, Italy; Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1978/07/29/078U0392/sg (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Garda, E.; Gerbi, G.; Lippolis, L.; Trevisio, L.A. L’ultima frontiera. Ipotesi progettuali per un hospice a Torino. In Progettare i Luoghi di Cura tra Complessità e Innovazione; Greco, A., Morandotti, M., Eds.; Edizioni TCP: Pavia, Italy, 2008; pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Alalouch, C.; Aspinall, P.A.; Smith, H. Design Criteria for Privacy-Sensitive Healthcare Buildings. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2016, 8, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- VV.AA. Il Quadro Esigenziale e Il Documento di Indirizzo alla Progettazione (D.I.P.) per l’intervento di “Riqualificazione, il restauro e la Rifunzionalizzazione del Complesso Monumentale di Santa Maria del Popolo degli Incurabili"; ASL Napoli 1 Centro: Napoli, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- VV.AA. Santa Maria del Popolo degli Incurabili, Studi Propedeutici alla Progettazione: Il Quadro Esigenziale e gli Indirizzi Metodologici; Giannini: Napoli, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- D’Auria, S.; Diana, L. The Regeneration of Public Heritage Estate in Campania: An Assessment Approach. SMC-Sustain. Mediterr. Constr. L. Cult. Res. Technol. 2020, 11, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Boaga, G. Un’ipotesi di metodo per la valutazione della compatibilità. In Flessibilità e riuso. Recupero Edilizio e Urbano, Teorie e Tecniche; Alinea Editrice: Firenze, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- MIsIrlIsoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteraglia, P. Risk, health system and urban project. Tema J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, Special Is, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, F. Edilizia: Progetto, Costruzione, Produzione; Edizioni Polistampa: Firenze, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Acampa, G.; Diana, L.; Marino, G.; Marmo, R. Assessing the transformability of public housing through BIM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A. Grundrissbildung und Raumgestaltung von Kleinwohnungen und neue Auswertungsmethoden [Plan design and spatial forms for the minimum dwelling and new methods of enquiry]. Zent. Der Bauverwalt. 1928, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, L. Metodo CRI_TRA: Un metodo di valutazione comparativa delle criticità e della trasformabilità edilizia del patrimonio residenziale pubblico in Italia. In L’analisi Multicriteri tra Valutazione e Decisione; Fattinnanzi, E., Mondini, G., Eds.; DEI Editore: Roma, Italy, 2015; pp. 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, C.; Nucara, A.; Pietrafesa, M. Does window-to-wall ratio have a significant effect on the energy consumption of buildings? A parametric analysis in Italian climate conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 13, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwetaishi, M.; Balabel, A.; Abdelhafiz, A.; Issa, U.; Sharaky, I.; Shamseldin, A.; Al-Surf, M.; Al-Harthi, M.; Gadi, M. User thermal comfort in historic buildings: Evaluation of the potential of thermal mass, orientation, evaporative cooling and ventilation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.L.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, C.Y.; Leigh, S.B.; Jeong, H. Window retrofit strategy for energy saving in existing residences with different thermal characteristics and window sizes. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2016, 37, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Peduzzi, A.; Diana, L.; Cascone, S.; Cecere, C. A sustainable approach towards the retrofit of the public housing building stock: Energy-architectural experimental and numerical analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampa, G. European guidelines on quality requirements and evaluation in architecture. Valori e Valutazioni 2019, 2019, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Stato Possiede (Solo) 62,8 Miliardi di Immobili. Available online: https://www.truenumbers.it/beni-pubblici/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Donatiello, G.; Gerosa. Rischio di Povertà o Esclusione Sociale in Calo Nell’anno Pre-Pandemia; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning Setting Priorities, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0070543713. [Google Scholar]

- Fedele, C. Un antico polo religioso tra borgo e suburbio: San Gennaro dei Poveri a Napoli. In Borgo dei Vergini. Storia e Struttura di un Ambito Urbano; Buccaro, A., Ed.; Electa: Napoli, Italy, 1991; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, S. Ospedali e Città nel Regno di Napoli. Le Annunziate: Istituzioni, Archivi e Fonti (secc. XIV-XIX); Casa Editrice Leo S. Olshki: Firenze, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, I. Atlante della Città Storica: I Quartieri Bassi e il Risanamento; Clean Edizioni: Napoli, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, R. Federico Travaglini: I Restauro tra Abbellimento e Ripristino; Electa: Napoli, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, I. Atlante della Città Storica: Dallo Spirito Santo a Materdei; Clean Edizioni: Napoli, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Cultural | Environmental | Economic | Market | Social | Physical | Functional |

| [40,43] | [40,43] | [40,41,42,43] | [43] | [40,41,42] | [41,42] | [41,42] |

| Continuity | Architectural | Changeability | Legal | Technological | Political | Location |

| [40] | [40] | [43] | [41,42,43] | [41,42] | [42] | [43] |

| Accessibility Score Normalization | Non-Use Ratio Score Normalization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Transportation Stations | Parking Lots | ||||

| 1 | r > 700 m | 1 | r > 500 m | 1 | DA < 30% |

| 2 | 500 m < r ≤ 700 m | 2 | 300 m < r ≤ 500 m | 2 | 30% ≤ DA < 50% |

| 3 | 400 m < r ≤ 500 m | 3 | 200 m < r ≤ 300 m | 3 | 50% ≤ DA < 80% |

| 4 | 300 m < r ≤ 400 m | 4 | 150 m < r ≤ 200 m | 4 | 80% ≤ DA < 100% |

| 5 | r ≤ 300 m | 5 | r ≤ 150 m | 5 | DA ≥ 100% |

| Availability of Services Score Normalization | |||||

| Primary Education | Secondary Education | ||||

| 1 | r > 1000 m | 1 | r > 1500 m | ||

| 2 | 700 m < r ≤ 1000 m | 2 | 1000 m < r ≤ 1500 m | ||

| 3 | 500 m < r ≤ 700 m | 3 | 850 m < r ≤ 1000 m | ||

| 4 | 400 m < r ≤ 500 m | 4 | 700 m < r ≤ 850 m | ||

| 5 | r ≤ 400 m | 5 | r ≤ 700 m | ||

| Health Services | Markets | ||||

| 1 | r > 1300 m | 1 | r > 1000 m | ||

| 2 | 1000 m < r ≤ 1300 m | 2 | 750 m < r ≤ 1000 m | ||

| 3 | 750 m < r ≤ 1000 m | 3 | 500 m < r ≤ 750 m | ||

| 4 | 500 m < r ≤ 750 m | 4 | 400 m < r ≤ 500 m | ||

| 5 | r ≤ 500 m | 5 | r ≤ 400 m | ||

| Usability Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 1 < Score ≤ 2 | 50.0% < U ≤ 72.0% |

| 2 < Score ≤ 3 | 72.0% < U ≤ 80.8% |

| 3 < Score ≤ 4 | 80.8% < U ≤ 86.6% |

| 4 < Score ≤ 5 | 86.4% < U ≤ 90.0% |

| Fragmentation Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 5 ≤ Score < 4 | 0.00% ≤ F < 4.40% |

| 4 ≤ Score < 3 | 4.40% ≤ F < 6.16% |

| 3 ≤ Score < 2 | 6.16% ≤ F < 7.28% |

| 2 ≤ Score < 1 | 8.00% ≤ F < 8.00% |

| Constructive Modifiability Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 5 ≤ Score < 4 | 1.00% ≤ CM < 14.40% |

| 4 ≤ Score < 3 | 14.40% ≤ CM < 19.67% |

| 3 ≤ Score < 2 | 19.67% ≤ CM < 22.85% |

| 2 ≤ Score < 1 | 22.85% ≤ CM < 25.00% |

| Roof Implementation Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 1 < Score ≤ 2 | 50.0% < RI ≤ 62.5% |

| 2 < Score ≤ 3 | 62.5% < RI ≤ 75.0% |

| 3 < Score ≤ 4 | 75.0% < RI ≤ 87.5% |

| 4 < Score ≤ 5 | 87.5% < RI ≤ 100.0% |

| External Envelope Wall Implementation Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 1 < Score ≤ 2 | 0.0% < EEI ≤ 25.0% |

| 2 < Score ≤ 3 | 25.0% < EEI ≤ 50.0% |

| 3 < Score ≤ 4 | 50.0% < EEI ≤ 75.0% |

| 4 < Score ≤ 5 | 75.0% < EEI ≤ 100.0% |

| Window-to-Wall Ratio Score Normalization | |

|---|---|

| 1 < Score ≤ 2 | 5.0% < WWR ≤ 12.5% |

| 2 < Score ≤ 3 | 12.5% < WWR ≤ 20.0% |

| 3 < Score ≤ 4 | 20.0% < WWR ≤ 27.5% |

| 4 < Score ≤ 5 | 27.5% < WWR ≤ 35.0% |

| ID | Municipality | Address | Lat. | Long. | … | Conser. Score | Context Score | Access. Score | Service Score | Non-Use Score | Potential Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | |||||||||||

| 145 | Napoli | Via Santa Maria la Nova 43 | 40.841 | 14.253 | … | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3.07 |

| 146 | Capua | Via Roma 25 | 41.110 | 14.215 | … | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2.14 |

| 147 | Nocera Inferiore | Via Francesco Salimena 120 | 40.748 | 14.640 | … | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1.68 |

| … | |||||||||||

| Code-Case Study (Location) | Year of First Construction (Main Renovations) | Original Function | Listed Building | Vertical Structure | Horizontal Structure | Vertical Envelope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGN—San Gennaro (Naples) | Mid-9th cent. (1468; 1656; end 19th cent., mid-20th cent.) | Monastery/Hospital | Yes | Masonry walls | Vaults/steel beam+ hollow blocks (or brick vaults) | Tuff |

| ANN—Annunziata (Naples) | 1343 (1433, 1540, 1757, 1888, 1948) | Hospital | Yes | Masonry walls | Vaults/steel beam + hollow blocks (or brick vaults)/wood/hollow blocks + r.c. beams | Tuff |

| GEM—Gesù e Maria (Naples) | 1580 (end 19th cent.) | Convent | Yes | Masonry walls | Steel beam + hollow blocks (or brick vaults) | Tuff |

| FRL—Presidio Frullone (Naples) | 1963 | Office + Healthcare facility | No | R.c. pillars | Hollow blocks + r.c. beams | Double hollow bricks with air space |

| PAL—Ex Biagio Lauro (Palma Campania) | 1965 (1985) | Hospital | No | Masonry walls/r.c. pillars | Hollow blocks + r.c. beams/steel beam + hollow blocks | Tuff/double hollow bricks with air space |

| ALL—Via Allende (Castellamare di Stabia) | 1975 | Healthcare facility | No | R.c. pillars | Hollow blocks + r.c. beams | Double hollow bricks with air space |

| Portion | Ground Floor | Portion | First Floor | Global | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Norm. | Result | Norm. | Result | Norm. | Result | Norm. | Result | Norm. | Weigh. | ||||

| Plan indicators | U | 71.00% | 1.95 | 60.22% | 1.46 | 96.80% | 5.00 | 77.60% | 2.64 | 68.95% | 1.86 | 0.166 | ||

| F | 2.57% | 4.42 | 3.13% | 4.29 | 2.80% | 4.36 | 2.22% | 4.49 | 2.69% | 4.39 | 0.166 | |||

| CM | 27.20% | 1.00 | 25.34% | 1.00 | 22.20% | 2.20 | 19.28% | 3.07 | 22.42% | 2.14 | 0.166 | |||

| RI | 74.30% | 2.93 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 84.01% | 3.72 | 0.166 | |||

| Façade indicators | Portion | East Façade | West Façade | South Façade | North Façade | |||||||||

| Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | |||||

| EEI | 21.00% | 1.84 | 24.72% | 1.99 | 41.18% | 2.65 | 6.60% | 1.26 | 14.59% | 1.58 | 20.77% | 1.83 | 0.166 | |

| WWR | 26.50% | 3.87 | 19.76% | 2.97 | 16.96% | 2.59 | 19.99% | 3.00 | 22.97% | 3.40 | 19.20% | 2.89 | 0.166 | |

| Final Score | 2.80 | |||||||||||||

| U | F | CM | RI | EEI | WWR | Transform. Index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | Result | Nor. | ||

| SGN | 53.51% | 1.16 | 6.73% | 2.49 | 24.75% | 1.03 | 93.48% | 4.48 | 40.59% | 2.62 | 12.29% | 1.97 | 2.29 |

| ANN | 66.76% | 1.76 | 4.18% | 4.18 | 18.58% | 3.21 | 32.57% | 1.00 | 6.80% | 1.27 | 9.52% | 1.60 | 2.15 |

| GEM | 68.95% | 1.86 | 2.69% | 4.39 | 22.42% | 2.14 | 84.01% | 3.72 | 20.77% | 1.83 | 19.20% | 2.89 | 2.80 |

| Year of Construction | Listed | Potential Index | Transformability Index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGN | Mid-9th cent./1468 | Yes | 2.36 | 2.29 |

| ANN | 1343 | Yes | 3.40 | 2.15 |

| GEM | 1580/End 19th cent. | Yes | 3.22 | 2.80 |

| FRL | 1963 | No | 2.35 | 3.46 |

| PAL | 1965 | No | 1.35 | 3.55 |

| ALL | 1975 | No | 2.32 | 3.29 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diana, L.; D’Auria, S.; Acampa, G.; Marino, G. Assessment of Disused Public Buildings: Strategies and Tools for Reuse of Healthcare Structures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042361

Diana L, D’Auria S, Acampa G, Marino G. Assessment of Disused Public Buildings: Strategies and Tools for Reuse of Healthcare Structures. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042361

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiana, Lorenzo, Saverio D’Auria, Giovanna Acampa, and Giorgia Marino. 2022. "Assessment of Disused Public Buildings: Strategies and Tools for Reuse of Healthcare Structures" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042361

APA StyleDiana, L., D’Auria, S., Acampa, G., & Marino, G. (2022). Assessment of Disused Public Buildings: Strategies and Tools for Reuse of Healthcare Structures. Sustainability, 14(4), 2361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042361