Models Underlying the Success Development of Family Farms in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

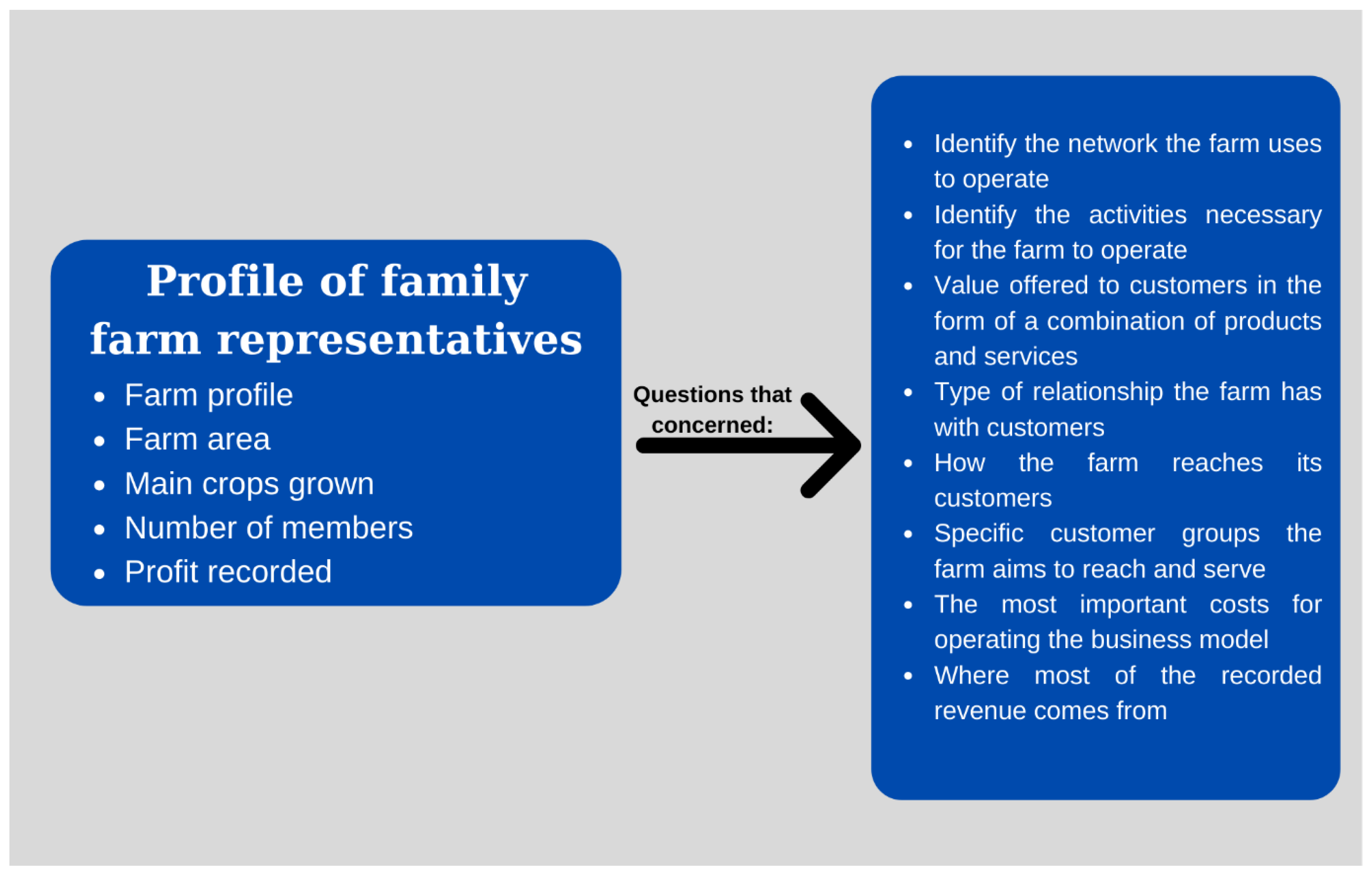

3. Methodology

- Adapting the BMC to the study purpose;

- Identify successful farms that can be a model for the development of other family farms following the same pattern (described in detail in the table below);

- Conduct interviews with stakeholders;

- Interpretation of the data obtained (BMC and SWOT analysis of the farms-of the case studies).

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meike, F. Small Farms in Europe: Viable but Underestimated; Eco Ruralis: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2017; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.; Hartel, T.; Kuemmerle, T. Conservation policy in traditional farming landscapes. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pretty, J.N.; Morison, J.I.L.; Hine, R.E. Reducing food poverty by increasing agricultural sustainability in developing countries. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 95, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarin, A.; Rivera, M.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Guimar, N.; Sumane, S.; Moreno-Perez, O.M. A new typology of small farms in Europe. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasson, R.; Errington, A.J. The Farm Family Business; Cab International: Wallingford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Dev. 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, M.; Guarin, A.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Almaas, H.; Mur, L.A.; Burns, V.; Czekaj, M.; Ellis, R.; Galli, F.; Grivins, M.; et al. Assessing the role of small farms in regional food systems in Europe: Evidence from a comparative study. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzi, S.; Belletti, G.; Biagioni, P. Integrated Supply Chain Projects and multifunctional local development: The creation of a Perfume Valley in Tuscany. Agric. Food Econ. 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samberg, L.H.; Gerber, J.S.; Ramankutty, N.; Herrero, M.; West, P.C. Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 124010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortan, M.; Vereş, V.; Baciu, L.; Raţiu, P. Family farms from Romania Nord Vest Region in the context of the rural sustainable development. In CES Working Papers; Centre for European Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; Volume 10, pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Darnhofer, I.; Lamine, C.; Strauss, A.; Navarrete, M. The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölling, B.; Prados, M.-J.; Torquati, B.M.; Giacchè, G.; Recasens, X.; Paffarini, C.; Alfranca, O.; Lorleberg, W. Business models in urban farming: A comparative analysis of case studies from Spain, Italy and Germany. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drejerska, N.; Bareja-Wawryszuk, O.; Gołębiewski, J. Marginal, localized and restricted activity: Business models for creation a value of local food products: A case from Poland. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Anastopoulos, C.; Papadopoulos, I.; Lazaridou, D. Business model for developing strategies of forest cooperatives. Evidence from an emerging business environment in Greece. J. Sustain. For. 2019, 39, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvarova, I.; Atstaja, D.; Vitola, A. Circular economy driven innovations within business models of rural SMEs. In Society. Integration. Education, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Rezekne, Latvia, 24–25 May 2019; Rezekne Academy of Technology: Rezekne, Latvia, 2019; Volume 6, pp. 520–530. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, M.; Rønningen, L. The Uplands after neoliberalism? The role of the small farm in rural sustainability. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, S. The redefinition of family farming: Agricultural restructuring and farm adjustment in Waihemo, New Zealand. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M. Still being the ‘good farmer’: (non-) retirement and the preservation of farming identities in older age. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janker, J.; Manna, S.; Rist, S. Social sustainability in agriculture—A system-based framework. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 65, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, P.; Ventura, F.; Ye, J. (Eds.) Constructing a New Framework for Rural Development; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davidova, S.; Bailey, A.; Dwyer, J.; Erjavec, E.; Gorton, M.; Thomson, K. Semi-Subsistence Farming-Value and Directions of Development; European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies Policy Department B Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Calo, A. Assemblage and the ‘good farmer’: New entrants to crofting in Scotland. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J. Seeing through the ‘good farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘productivist’ behaviour. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, I.; Clark, G.; Crockett, A.; Ilbery, B.; Shaw, A. The development of alternative farm enterprises: A study of family labour farms in the Northern Pennines of England. J. Rural Stud. 1996, 12, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Lobley, M.; Whitehead, I. (Eds.) Keeping It in the Family: International Perspectives on Succession and Retirement on Family Farms; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Röös, E.; Fischer, K.; Tidåker, P.; Nordström Källström, H. How well is farmers’ social situation captured by sustainability assessment tools? A Swedish case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanzel, P. Five Big Questions about Five Hundred Million Small Farms. In Proceedings of the IFAD Conference on New Directions for Smallholder Agriculture, Rome, Italy, 24–25 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Calo, A.; De Master, K.T. After the incubator: Factors impeding land access along the path from farmworker to proprietor. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, N.M.; Fuller, A.M. Newcomers to farming: Towards a new rurality in Europe. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogràf. 2016, 62, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization, Family Farming—Romania; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/countries/rou/en/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Korzenszky, A. Extrafamilial farm succession: An adaptive strategy contributing to the renewal of peasantries in Austria. Can. J. Dev. Stud.-Rev. Can. D Etudes Dev. 2019, 40, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirner, L.; Kratochvil, R. The role of farm size in the sustainability of dairy farming in Austria: An empirical approach based on farm accounting data. J. Sustain. Agric. 2006, 28, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subic, J.; Jelocnik, M.; Jovanovic, M. Evaluation of social sustainability of agriculture within the Carpathians in the Republic of Serbia, Scientific Papers Series. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2013, 13, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Joosse, S.; Grubbström, A. Continuity in farming—Not just family business. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 50, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhmonen, I. The resilience of Finnish farms: Exploring the interplay between agency and structure. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 80, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvasti, T. Bending Borders of Gendered Labour Division on Farms: The Case of Finland. Sociol. Rural. 2003, 43, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, J.; Saarela, S.-R.; Söderman, T.; Kopperoinen, L.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Väre, S.; Kotze, D.J. Using the ecosystem services approach for better planning and conservation of urban green spaces: A Finland case study. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 3225–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F. Investigating dairy farmers’ resilience under a transforming policy and a market regime: The case of north karelia, Finland. Quaest. Geogr. 2017, 36, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EUROSTAT. Agricultural Land Market Regulations in the EU Member State; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://www.europeanlandowners.org/images/AGRI__LAND_MARKET_REGULATIONS_IN_THE_EU_/Agri-Land_EU_-_D3_-_ADDENDUM_with_Country_reports_final-3.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization, Family Farming—Finland; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/countries/fin/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Borys, B.; Slosarz, P. A note on the opinions of farmers from lowland regions of Poland concerning factors affecting the operation of their family farms on the threshold of accession to the EU. In Livestock Farming Systems in Central and Eastern Europe; EAAP European Association for Animal Production Technical Series; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska, S. Family Farming in Poland and in the World—Thematic Edition of Wies i Rolnictwo [Countryside and Agriculture] Quarterly Magazine. East. Eur. Countrys. 2016, 22, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csaki, C.; Lerman, Z. Land and farm structure in transition: The case of Poland. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2002, 43, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcyn, J. Eco-Efficiency and Human Capital Efficiency: Example of Small- and Medium-Sized Family Farms in Selected European Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borychowski, M.; Stepien, S.; Polcyn, J.; Tosovic-Stevanovic, A.; Calovic, D.; Lalic, G.; Zuza, M. Socio-Economic Determinants of Small Family Farms’ Resilience in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętara, W.; Adamski, M. Competitiveness of the Polish Dairy Farms at the Background of Farms from Selected European Union Countries. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2018, 1, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaudio, G. I Processi di Cambiamento Dell’agricoltura Familiare tra Produzione, Mercati e Territori; CREA—Consiglio per la Ricerca in Agricoltura e L’analisi Dell’economia Agrarian: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vastola, A.; Zdruli, P.; D’Amico, M.; Pappalardo, G.; Viccaro, M.; Di Napoli, F.; Cozzi, M.; Romano, S. A comparative multidimensional evaluation of conservation agriculture systems: A case study from a Mediterranean area of Southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, S.; Leseigneur, A.; Gaillard, C. Family farms and generation replacement: The example of the canton of Seurre in Cote d’Or (France). Cah. Agric. 2006, 15, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becot, F.A.; Inwood, S.M. The case for integrating household social needs and social policy into the international family farm research agenda. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 77, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilg, A.W.; Battershill, M. The role of household factors in direct selling of farm produce in France. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 1999, 90, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupre, L. Distinctive features of wage labour in family livestock farming: An initial approach based on a case study in the Northern Alps (France). Cah. Agric. 2010, 19, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, G.; Petrović, M.D.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Radovanović, M.; Vuković, N. Can Proper Funding Enhance Sustainable Tourism in Rural Settings? Evidence from a Developing Country. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, N.-M.; Ruhstorfer, P.; Kurzrock, B.-M. Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, E.A.; Ursu, A.; Tudor, V.C.; Micu, M.M. Sustainable Development of the Rural Areas from Romania: Development of a Digital Tool to Generate Adapted Solutions at Local Level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.M.; Xu, S.; Sutherland, L.-A.; Escher, F. Land to the Tiller: The Sustainability of Family Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurich, A.; Penicka, A.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Lindenthal, T.; Quendler, E.; Zollitsch, W. Elements of Social Sustainability among Austrian Hay Milk Farmers: Between Satisfaction and Stress. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhart, V.R.; Vogel, S.; Larcher, M. Determinants of family farm successions in Austria-a multi-variant analysis with farm-related, social and emotional factors. Ber. Landwirtsch. 2018, 96, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru, E.A.; Petre, L.I. Family Farm—Solution for Sustainable Development of Rural Area. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium “Agricultural Economics and Rural Development—Realities and perspectives for Romania”, Bucharest, Romania, 18 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Bernarda, G.; Smith, A. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Imbiri, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N.; Statsenko, L. A Novel Taxonomy for Risks in Agribusiness Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjirchi, S.M.; Shojaei, S.; Sadrabadi, A.N.; Jalilian, N. Promotion of solar energies usage in Iran: A scenario-based road map. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirado, C.; Valldeperas, N.; Tulla, A.F.; Sendra, L.; Badia, A.; Evard, C.; Cebollada, À.; Espluga, J.; Pallarès, I.; Vera, A. Social farming in Catalonia: Rural local development, employment opportunities and empowerment for people at risk of social exclusion. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem, M.A.; Fitrihana, N. Bussines model canvas of teaching factory fashion design competency Vocational High School in Yogyakarta. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; p. 1273. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, B. A Framework for Business Model Innovation. In Proceedings of the IMRC Conference, Bangalore, India, 16–18 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Amuzu, J. Farmcrowdy: Digital business model innovation for farming in Nigeria. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2019, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.P.; Sarangi, K.; Sangeetha, M.; Shasani, S.; Saik, N.H. SWOT Analysis of Agriculture in Kandhamal District of Orissa, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1592–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidreza, S.M.; Hamed, F. Designing an Integrated AHP based Fuzzy Expert System and SWOT Analysis to Prioritize Development Strategies of Iran Agriculture. Rev. Int. Comp. Manag. 2012, 13, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanmaneepong, S.; Fakkhong, S.; Kullachai, P. SWOT analysis and marketing strategies development of agricultural products for community group in Nong Chok, Bangkok, Thailand. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2018, 14, 2027–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, F.; Sadighi, H.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Farhadian, H. An E-Commerce SWOT Analysis for Export of Agricultural Commodities in Iran. J. Agric. Sci. Tech. 2019, 21, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Butu, A.; Brumă, I.S.; Tanasă, L.; Rodino, S.; Dinu Vasiliu, C.; Doboș, S.; Butu, M. The Impact of COVID-19 Crisis upon the Consumer Buying Behavior of Fresh Vegetables Directly from Local Producers. Case Study: The Quarantined Area of Suceava County, Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case Study 1 | |

| Type of business | Medium-sized farm specialising in growing cereal and oilseed crops |

| Main crops | Rapeseed, sunflower, wheat, maize |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 2 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 15,264 euro/year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 2 | |

| Type of business | Small-scale farm specialising in growing vegetables |

| Main crops | Tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 4 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 30,528 euro/ year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 3 | |

| Type of business | Small-scale farm specialising in growing vegetables |

| Main crops | Tomatoes, eggplants, peppers |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 2 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 15,264 euro/year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 4 | |

| Type of business | Medium-sized farm specialising in growing cereal and oilseed crops |

| Main crops | Rapeseed, sunflower, wheat, maize |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 2 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 15,264 euro/year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 5 | |

| Type of business | Small-scale farm specialising in growing leguminous crops |

| Main crops | Soybeans, peas |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 3 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 22,896 euro/ year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 6 | |

| Type of business | Small-scale farm specialising in growing vegetables |

| Main crops | Cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 2 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 15,264 euro/year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

| Case Study 7 | |

| Type of business | Small-scale farm specialising in growing vegetables |

| Main crops | Cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers |

| No. of family members working on the farm | 3 |

| Farm profitability | Farm profitability ≥ 22,896 euro/year |

| Type of farming | Ecological |

(PC) Key Partners and Partnerships

| (AC) Key Activities

| (PV) Value Proposal

| (RC) Customer Relations

| (SC) Market segments

| |

(KR) Key Resources

| (CA) Channel

| ||||

(SC) Cost Structure

| (FV) Revenue Flow

| ||||

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

Economic

| Development

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

Social

| Economic

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Micu, M.M.; Dumitru, E.A.; Vintu, C.R.; Tudor, V.C.; Fintineru, G. Models Underlying the Success Development of Family Farms in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042443

Micu MM, Dumitru EA, Vintu CR, Tudor VC, Fintineru G. Models Underlying the Success Development of Family Farms in Romania. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042443

Chicago/Turabian StyleMicu, Marius Mihai, Eduard Alexandru Dumitru, Catalin Razvan Vintu, Valentina Constanta Tudor, and Gina Fintineru. 2022. "Models Underlying the Success Development of Family Farms in Romania" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042443

APA StyleMicu, M. M., Dumitru, E. A., Vintu, C. R., Tudor, V. C., & Fintineru, G. (2022). Models Underlying the Success Development of Family Farms in Romania. Sustainability, 14(4), 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042443