A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How can cultural heritage be identified in rural settlements that have the potential to form cultural routes?

- How was the cultural route formed and changed? How have these productive activities along the route shaped the spatial structure of rural settlements and influenced the relationship between humans and nature?

- How can traditional villages be revitalized through the lens of culture and landscape?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

3. Results

3.1. An Evolving Framework of Cultural Routes

3.1.1. Characteristics Associated with Traditional Villages

- The overall value of cultural routes. The cultural route connecting a series of spatially dispersed traditional settlements demonstrates value as a whole, transcending each part that shares a substantial number of characteristics and a value system.

- The connecting function of the cultural corridor. The linear transportation entities are infiltrated and linked with the material and immaterial derivatives around the cultural routes. This structure can promote the renewal of decaying communities and infrastructure along the route, forming a continuous public space with cultural themes.

- The perspective of dynamic development. In the past, different communities conducted cultural exchanges and integration through the route. Currently, it is an extension of spatial and temporal dimensions as well as the dialog between the past and the future. Attention should be given to the role of the route in promoting the exchange of different groups recently, implementing it in spatial construction, integrating the cultural route into the process of rural revitalization, and promoting the harmonious coexistence of historical heritage and contemporary society.

3.1.2. Elements of the Cultural Route in Chishui

3.1.3. Topographical Basis for Cultural Routes

- Two main clusters: In the northwest, the triangle, lowland downtown areas are the most widely populated, where the terrain undulates slowly along the ridge less than 500 m; the fan area next to it is a hilly, low mountain basin, with a gentle topography of approximately 600 m on average. Both clusters share some similar geographic traits: the slope ranges from 5 to 15 degrees, and the slope aspect is delicately segmented.

- Two valley lines: Settlements aggregate alongside the mountain canyon and river valleys, forming two linear distributions of the Chishui River and Xishui River. The lower reaches of the Xishui River are much broader than those of the Chishui River, resulting in a relatively wider buffering zone capable of more towns and villages.

- The selected traditional settlements are all located along the Chishui River, and their spatial distribution follows the river’s zigzag trend, forming a meandering linear route. The topographic conditions of the mountains dictate that settlements can only expand linearly in a narrow space sandwiched between the foot of the mountains and the river’s edge.

3.2. Salt Transportation: Dynamics of the Evolution of Traditional Villages

3.2.1. Background

3.2.2. The Historic Route

3.2.3. Settlements along the Route

3.3. A Multi-Cultural Route in New Era

3.3.1. Route Shifting from Waterways to Highways

- Salt supply. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the supply of salt in Guizhou was no longer a problem. In the past, however, salt transportation was so dangerous that crews and pickers had frequent accidents, which led to strikes and economic disputes. From 1950 onward, the government macroregulated and expanded the salt supply market to suppress the price of salt. The Chishui section of the Chishui-Tongzi highway (S301) was opened in 1959, which eased the demand for salt transportation on the Chishui River.

- Shipping modernization. In the late 1950s, several steamships were commissioned in the Chishui Basin, three of which were allocated from the central government. Infrastructure in the Chishui Basin was built sequentially, including hydroelectric power stations, bridges, and modern docks. The Chishui River has opened up routes for long-distance transportation in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and Chishui–Chongqing passenger transport. It was not until the dawn of the 21st century that shipping ceased and the ferry service to Chongqing stopped operating in 2001. The following year, the Bing’an pedestrian bridge across the Chishui River was completed, and the Bing’an ferry was concurrently cancelled.

- Ecological restoration. For a long time, the biodiversity of the Chishui River basin continued to decline due to overfishing. The State Council approved the listing of the Chishui River in the “National Nature Reserve of Rare and Endemic fish in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River” in 2005. However, it failed to prevent the Guizhou section of the Chishui River from being severely polluted by 2012. China banned all fishing activities in the Chishui River basin from 2017 to 2026 to restore the ecological environment. The Decision on Strengthening the Joint Protection of the Chishui River basin entered into force in 2021 as a reliable guarantee of the rule of law. Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan provinces jointly established a 200 million RMB ecological compensation fund for the entire Chishui River Basin. Guizhou has revised the regulations accordingly, formulated and implemented reform programs such as the delineation of the ecological red line in the basin, and paid for the use of water resources, ecological compensation, third-party management of environmental pollution, and river chief systems to strengthen environmental supervision.Despite these recent findings regarding the declining role of river transport in the modern era, ecological restoration has arisen as the most critical issue for the Chishui River in recent decades. Nevertheless, the transportation function of waterways has been increasingly replaced by highways.The second change involved road construction.

- Highway construction. As mentioned above, road infrastructure has been carried out since 1959; however, it was not until forty years later that the last township road was completed in Chishui. At the end of 2013, the Renhuai–Chishui Expressway was opened to traffic, constituting a major part of the red tourism route as well as an economic trunk line. Since 2017, the construction of transportation infrastructure has been accelerated. As part of a full provincial transportation construction program, the Chishui River Valley Tourist Highway, which traces the historical salt waterway from Maotai to Chishui City, was officially completed in 2017. It consists of 160 km of mountain bike riding routes and 154 km of motorized routes, forming a slow-moving system to facilitate tourism alongside the river. The dramatic rise of road networks has created a new economic path for isolated towns in the southwestern region, bringing benefits to local residents and attracting tourists to boost the regional economy.

- Benefits andvisions. Highway construction strengthens ethnic unity and progress, and further accelerates the development process in northern Guizhou by promoting local resource utilization, tourism development, and poverty alleviation. Initially, the government organized a series of historical conservation and rural planning projects on the basis of improved infrastructure. As a famous Chinese historical and cultural village and town, conservation plans were prepared for Bing’an (2012) and Datong (2019). Subsequently, development plans were organized and prepared for traditional town preservation, tourism, and poverty alleviation. Relying on the Chishui River Valley Highway, the Tourism Development Plan 2019–2030 is a medium- to long-term project aimed at enhancing the prosperity of the Basin Resort.

- Interference with settlements. Inevitably, however, highways bring some disadvantages to settlements. The new layouts are heavily dominated by road systems, reflecting the overwhelming priority of accessibility over topographic habitability in site selection, whereas traditional settlements follow the obverse logic. With respect to the environment, traditional habitats extend to the river by creeping along the mountainous alignment. As a result, new clusters were developed alongside the highway, disrupting the continuity of pedestrian systems and failing to create an orderly living space (see Figure 10). New clusters often lack a sense of spatial enclosure and disregard the scale of the streets and alleys. The terrible result that emerges in Bing’an is the tourist service buildings that lined the road and seriously obstructed the natural environment (see Figure 12 and Figure 13). Although they are all predominantly linear, the old clusters have a certain thickness consisting of several rows of traditional long units (see Figure 14).

3.3.2. Cultural Heritage in Traditional Villages

3.3.3. Multi-Cultural Route for Rural Revitalization

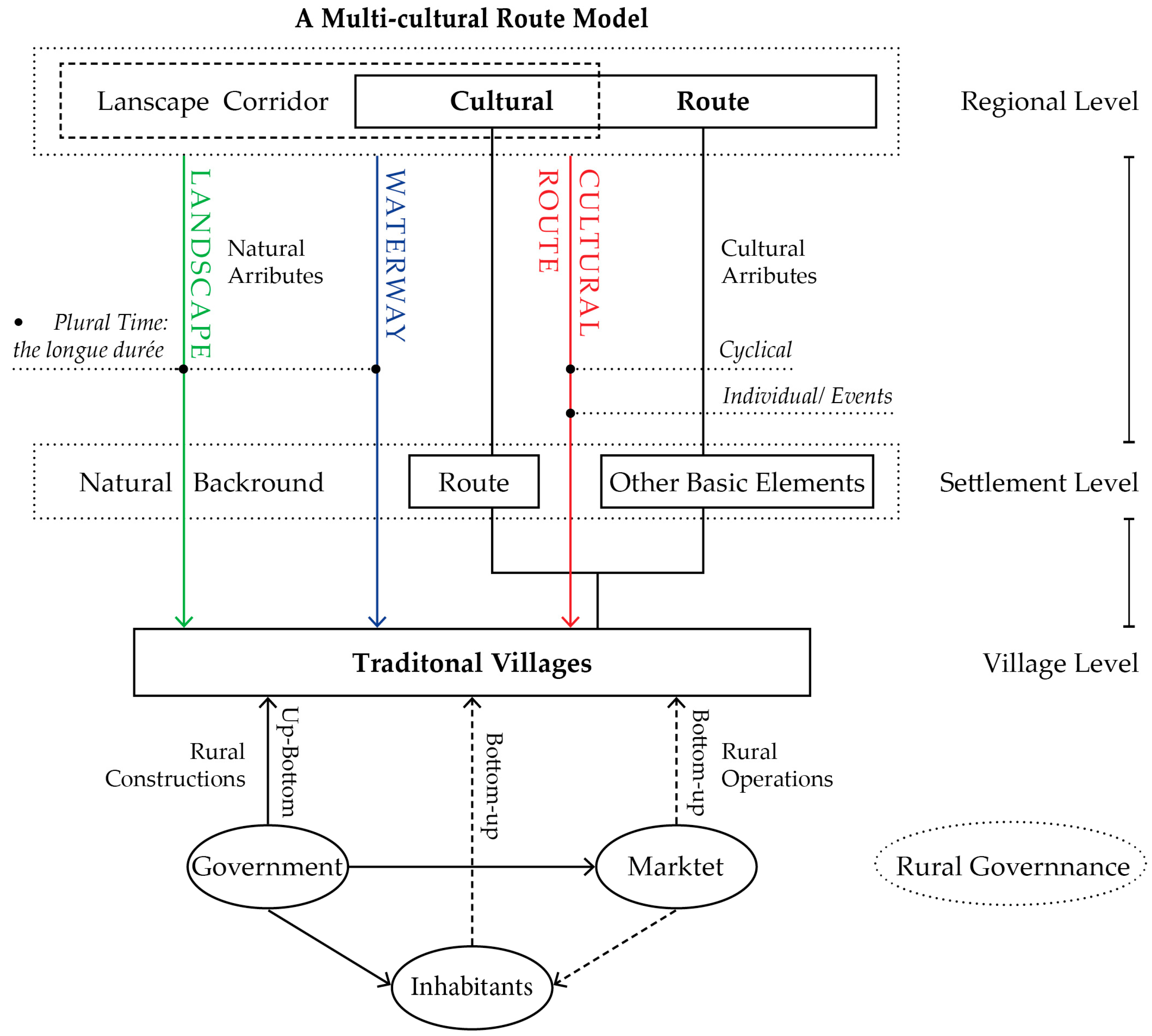

- From a topographical perspective, landforms are the basis of human activities, while the river serves as the route’s ontology [48]. Ecological restoration programs are expected to recall the historical salt transport route through experiential programs in the future. Alsophila vegetation cover has been protected as a national nature reserve. According to the local conditions, the implementation of returning fallow to bamboo forest makes bamboo a powerful tool to combat poverty and promote rural revitalization. This concept as well as biodiversity conservation and recreation are the most frequent scope of landscape corridors [49], and they share some of the same values as cultural routes. Cultural heritage is mainly present in traditional settlements, including the route ontology and other substantial elements.

- From a plural time perspective, Braudel identified three dimensions of history and social time that have cultural potential [50]. First, the environmental effects of the longue durée have framed the geographical ground of the human route. Second, cyclical human activities involving socio-economic and cultural attributes have formed historical transportation routes that have lasted for hundreds of years. In parallel to transporting goods, the route also transported migrants and disseminated culture, which created a unique cultural landscape in the basin. These influences eventually manifested in the patterns and townscapes of traditional settlements. Finally, the events of the “four crossings of the Chishui River” are concentrated in recent history and overlaid on cultural routes to render the Red Culture alive.

- From a rural governance perspective, three main forces affect the tourism development of cultural routes. The government establishes regulations and leads rural construction from top to bottom, while the marketplace serves as the implementation platform for the conversion of capital to the countryside into rural operations [51]. However, the bottom-up approach, through the everyday life of the inhabitants, has undeniable weight for the preservation and sustained adoption of cultural routes. Furthermore, the connected nature of cultural routes requires cooperation in governance and management at the village-to-village, settlement, and regional levels.

- From a tourism perspective, a multi-cultural route may proceed from three symbolic paths: a waterway in blue, a landscape corridor in green, and a cultural route in red. The multi-cultural route has remarkably expanded its scope and purposes within the above paths. The appeal of a single element is limited, while a multi-cultural framework integrates landscape corridors and cultural routes as a whole with far more significant attractions, similar to how ancient routes have performed in the past. Market-oriented tourism can implement cultural routes while bringing about the flow and intermingling of people, capital, and culture, which ultimately contributes to the upgrading of infrastructure and the improvement of the living standards of its inhabitants.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bochkov, D. Multiple nature-cultures, diverse anthropologies. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28, 538–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P. Country backwater to virtual village? Rural studies and ‘the cultural turn’. J. Rural Stud. 1997, 13, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, A. Free-time habitation and layers of ecological history at a southern Finnish lake. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 61, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Shao, R.; Lan, W.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y. Space Gene. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 43, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Landscape Analysis of Traditional Villages; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Traditional Villages in the Middle Reaches of Nanxi River; SDX Joint Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J. Analysis of Town Space: Spatial Structure and Morphology of Ancient Towns in Taihu River Basin; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.F.; Li, Y.R.; Lu, Z.; Pan, W. What makes better village economic development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from 338 villages. Habitat Int. 2020, 106, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Heritage policy meets community praxis: Widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, G.U. Urban morphology: An introduction and evaluation of the theories and the methods. City Plan. Rev. 2001, 25, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yao, S.; Tian, Y. The Theory and Localization About Typo-morphological Approach. Urban Plan. Int. 2017, 32, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.; Gu, K.; Whitehand, S.M.; Zhang, J. Urban morphology and conservation in China. Cities 2011, 28, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. From the City to the Construction: A New Dimension in the Architecture of the City. World Archit. 2021, 10, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Ding, W. A Study on a Collective Architectural Type and the Morphology of a Villagey: A Case Study of Shangzhuang Village in Yangcheng, Shanxi Province. Archit. J. 2017, 05, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Ding, W. Towards a Synthetic Typology: The Comparision between the Third Typology and Typomorphology. Architect 2017, 01, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yamu, C.; van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s Legacy: Space Syntax—A Synopsis of Basic Concepts, Measures, and Empirical Application. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, T.; Adeyeye, K. A Comparative Study of Urban Spatial Characteristics of the Capitals of Tang and Song Dynasties Based on Space Syntax. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Genealogical identities. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2002, 20, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. Cultural Route as a Type of World Heritage:An Interpretation to the ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. Urban Plan. Forum 2009, 04, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge University Press. ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes: Prepared by the International Scientific Committee on Cultural Routes (CIIC) of ICOMOS. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Québec, QC, Canada, 4 October 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Q.H.; Gan, F.; Zhang, P.; Lankton, J.W. Silk Road glass in Xinjiang, China: Chemical compositional analysis and interpretation using a high-resolution portable XRF spectrometer. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 2128–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, M. European Cultural Routes: Building a Multi-Actor Approach. Mus. Int. 2017, 69, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabow, S. The Santiago de Compostela Pilgrim Routes: The Development of European Cultural Heritage Policy and Practice from a Critical Perspective. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2010, 13, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowball, J.D.; Courtney, S. Cultural heritage routes in South Africa: Effective tools for heritage conservation and local economic development? Dev. S. Afr. 2010, 27, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Jovičić, A.; Pejnišević, I. Cultural Route and Ecomuseum Concepts as a Synergy of Nature, Heritage and Community Oriented Sustainable Development Ecomuseum “Ibar Valley” in Serbia. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hackenberg, R.A. Closing the Gap Between Anthropology and Public Policy: The Route Through Cultural Heritage Development. Hum Organ. 2002, 61, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai-hao, L.; Jianhua, Z.; Li, H.; Jian, G. One cultural route span the millenary: Chinese Tea Road. In Proceedings of the Monuments and Sites in Their Setting—Conserving Cultural Heritage in Changing Townscapes and Landscapes, Xi’an China, 17–21 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Moropoulou, A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: The case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 14, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H. “Sell Salt from Sichuan to Guizhou” and the Social Interaction along Chishui River Valley. J. Sichuan Univ. Sci. Eng. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Wei, D. Study on the route of Sichuan salt from Ren’an River into Guizhou and its role. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 40, 3006–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lou, Q. Research on the conservation of linear cultural heritage in southwest China: The example of the route of Sichuan salt into Qian. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2017, 329, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Jin, Q. On the Influence of the Course for Salt Transportation from Sichuan to Guizhou upon the Economy in Chishui district. J. Zunyi Norm. Coll. 2016, 18, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cheng, S. A Study on the Morphology and Survival Rationality of Ethnic Buyi Settlements in Baishui Valley, Guizhou Province. Archit. J. 2018, 3, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wang, N.; Fang, M. Sustainable Mountain Village Construction Adapted to Livelihood, Topography, and Hydrology: A Case of Dong Villages in Southeast Guizhou, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Li, D. Research of Multiple Time-space Cultural Superimposition in Siduchishui Area. Urban Dev. Stud. 2014, 21, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perceptions, Attitudes, and Values; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; de Bustamante, I.; Pascual-Aguilar, J.A. Using old cartography for the inventory of a forgotten heritage: The hydraulic heritage of the Community of Madrid. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehand, J.W.R. Basis for an Historical Geographical Theory of Urban Form. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1977, 2, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.R. Green space in urban morphology: A historico-geographical approach. Urban Morphol. 2019, 23, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, R.; Rodriguez, J.; Coronado, J.M. Modern roads as UNESCO World Heritage sites: Framework and proposals. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qi, L. Construction and practice of a conservation plan implementation evaluation system for historic villages. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dretske, F.I. Laws of Nature. Philos. Sci. 1977, 44, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbert, P.M. The Ch’ing Imperial Household Department: A Study of Its Organization and Principal Functions, 1662–1796; Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X. From the Soil, the Foundations of Chinese Society: A Translation of Fei Xiaotong’s Xiangtu Zhongguo, with an Introduction and Epilogue; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.P.; Gu, K.; Whitehand, J.W.R. Comparing Traditional Urban Form in China and Europe: A Fringe-belt Approach. Urban Geogr. 2012, 33, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Li, X. The Path and Strategy of the Revival of Old City in the View of Cultural Routes-Taking Lingchuan County of Shanxi Province as an Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, K.; Ibrahim, P.H.; Wahab, N.A.A. Conceptual Framework of Rural Landscape Character Assessment to Guide Tourism Development in Rural Areas. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 24, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Plieninger, T.; Primdahl, J. A Systematic Comparison of Cultural and Ecological Landscape Corridors in Europe. Land 2019, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braudel, F. History and the Social Sciences: The Longue durée. In On History, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1982; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aigwi, I.E.; Filippova, O.; Ingham, J.; Phipps, R. From drag to brag: The role of government grants in enhancing built heritage protection efforts in New Zealand’s provincial regions. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Contemporary Chinese Village Family Culture: An Exploration of the Modernization of Chinese Society; Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe: Shanghai, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The Reform of the Rural-Urban Dualism. J. Peking Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2008, 45, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C. Zhenggang LIU, “Floating East and Marching West: A Comparison between Taiwan and Sichuan about Fujianese and Cantonese Immigrants in the Qing Period”. J. Hist. Anthropol. 2006, 4, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C. Ethnic Distinctions and Ethnic Transformation. J. Hist. Anthropol. 2004, 2, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Stanek, L. Architecture as Space, Again? Notes on the Spatial Turn. Le J. Speciale’Z 2012, 4, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, N.D. The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1992, 21, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cheong, K.C.; Wang, Q.Y.; Li, Y.R. Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Gao, W.; Lv, Y.Q. The Triple Logic and Choice Strategy of Rural Revitalization in the 70 Years since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, Based on the Perspective of Historical Evolution. Agriculture 2020, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Shen, Y.; Yang, X.X.; Wang, Z.F.; Xu, L.Y. Where to Revitalize, and How? A Rural Typology Zoning for China. Land 2021, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, A. Cultural Commodities in Japanese Rural Revitalization: Tsugaru Nuri Lacquerware and Tsugaru Shamisen; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Chou, R.J. Cultural Landscape Development Integrated with Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of Songkou Ancient Town. Land 2021, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, M.M.; Zhou, L.; Liang, X.J.; Wang, W. Identifying the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Traditional Villages in China: A Multiscale Perspective. Land 2020, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Past | Present | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route | Physical Elements | Waterway | Mainstream, Tributaries, Port | All-year navigation | |

| Tools | Different sizes of ships | ||||

| Land Road | Valley Road, Streets in towns, Bridges | Viaduct, Highway, Tunnels | |||

| Tools | Pickers, Horses | ||||

| Human Activities | Goals | ‘Sichuan salt into Guizhou’ | Closed fishing; Ecological restoration | ||

| Other Substantive Elements | Tangible Heritage | Human Settlements | Interior | Central Hall, Fire Pond, Wood Structure Rooftop Food Storage | Power and home appliances |

| Architecture | Temple, Guild Hall, Pavilion, Retails Celebrities’ former residence, Accommodation, Dwellings | Tourist service facilities, Schools, Dwellings, Government institutions | |||

| Construction | Dock, Bridge, Boundary stone | ||||

| Public space | Square, Street, Lane, Yard | Parking | |||

| Unformal space | Market, Bazaar, Festival site | ||||

| Nature | Cultural landscapes | Tourism | |||

| Mountain, River, Forest, Farmland, Benchland | |||||

| Intangible Heritage | local | Tourism | |||

| Nature worship, Living habits, Dragon king worship | |||||

| Immigration | Shipping technology, Trade culture | ||||

| Central plain culture and custom | |||||

| education and the imperial examinations | |||||

| Year | Dynasty Calendar | Leading Individuals | Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1736 | the 1st year of Qianlong | Huang Tinggui (Sichuan governor) | Established four main ports and the route of “Sichuan salt into Guizhou” |

| 1743 | the 8th year of Qianlong | Zhang Guangsi (Guizhou governor-general) | The first river channel dredging |

| 1877 | the 3rd year of Guangxu | Ding Baozhen (Sichuan governor-general) | Reform of salt policy The second river channel dredging |

| 1941 | the 29th year of the Republic China | Nationalist Party’s River committee | The third river channel dredging |

| Element Type | Time | Site | Function | Patron | Worship God | Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | Ming Dynasty | Lower Dock | Salt port | Government and indigenous people | “Sichuan salt into Guizhou” | |

| Upper Dock | ||||||

| Architecture | Qing Dynasty | (1) Kanli Palace | Meeting, Worship, Temple fair | Salt merchants | River God: Zhenjiang Duke | an armed uprising in 1935 |

| (2) Wanshou Palace | Jiangxi Guild Hall, Worship | Jiangxi Salt merchants | Tao: Xu Xun | |||

| (3) King Yu’s Palace | Worship | Hunan/Hubei merchants | King Yu who tamed the flood | |||

| (4) Guanyin Temple | Worship, Salvation | Indigenous people | Buddha: Guanyin | 1739 floods 1862 war |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Zheng, X. A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042468

Zhou Z, Zheng X. A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042468

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Zijie, and Xin Zheng. 2022. "A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042468

APA StyleZhou, Z., & Zheng, X. (2022). A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China. Sustainability, 14(4), 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042468