1. Introduction

One of the earliest mentions of wine tourism dates back to 1935 when Joseph Burckel wanted to connect winegrowers in the villages of the Rhineland-Palatinate region through the form of a wine route and thus encourage increased wine sales [

1]. When visiting a particular tourist destination where vines are grown, or wine consumption is organized, tourists look for authentic and unique experiences, exchange positive impressions with others, and get to know cultural activities and attractions.

The first definitions of wine tourism appeared in the 1980s in articles such as “Wine tourism on the Moselle” [

2] but only began to appear more consistently in the following decade [

3]. According to Hall et al. [

4], this form of tourism can be defined as tourism that includes visits to vineyards, wineries, wine exhibitions, and wine festivals where the main motive of tourists is to experience the attractions of the wine-growing region and the consumption of different wines. When defining wine tourism, Coroș et al. [

5] state it as a form of rural tourism, provided that it is realized on the territory of vineyards or in cellars for storage and production of wine. According to the authors, this development occurs from a desire of winemakers and other entrepreneurs to use the growing demand for quality wine and start an additional business from areas of food services by opening wine cellars or shops dedicated to wine distribution where wine sales are realized, but and additional gastronomical offer also exists. With its development, wine tourism became a more important subject of study, which has led to an increase in research in this area and a growing number of academic articles [

6]. A similar conclusion is stated by Mitchel and Hall [

7], emphasizing that wine tourism is a broad research area studied by a large number of authors where seven subareas of research can be identified: Wine tourism product; Wine tourism and regional development; Quantifying winery visitation; Segmentation of the winery visitation market; Winery visitor’s behaviour; Nature of visit to wineries; Food safety and wine tourism. The participation of wine tourism in the total tourist offer of many countries has been increasing during the past decade. Wine tourism in the world is most often developed in wine routes. They can be defined as a unique form of selling agricultural, catering, and tourist products of a wine region where family farms, together with other legal entities and individuals, offer their products (primarily wine and brandy from their own production and other indigenous products and specialities). This form of wine tourism is complemented by the natural beauty of the region through which it passes and its cultural and historical content and tradition [

8,

9].

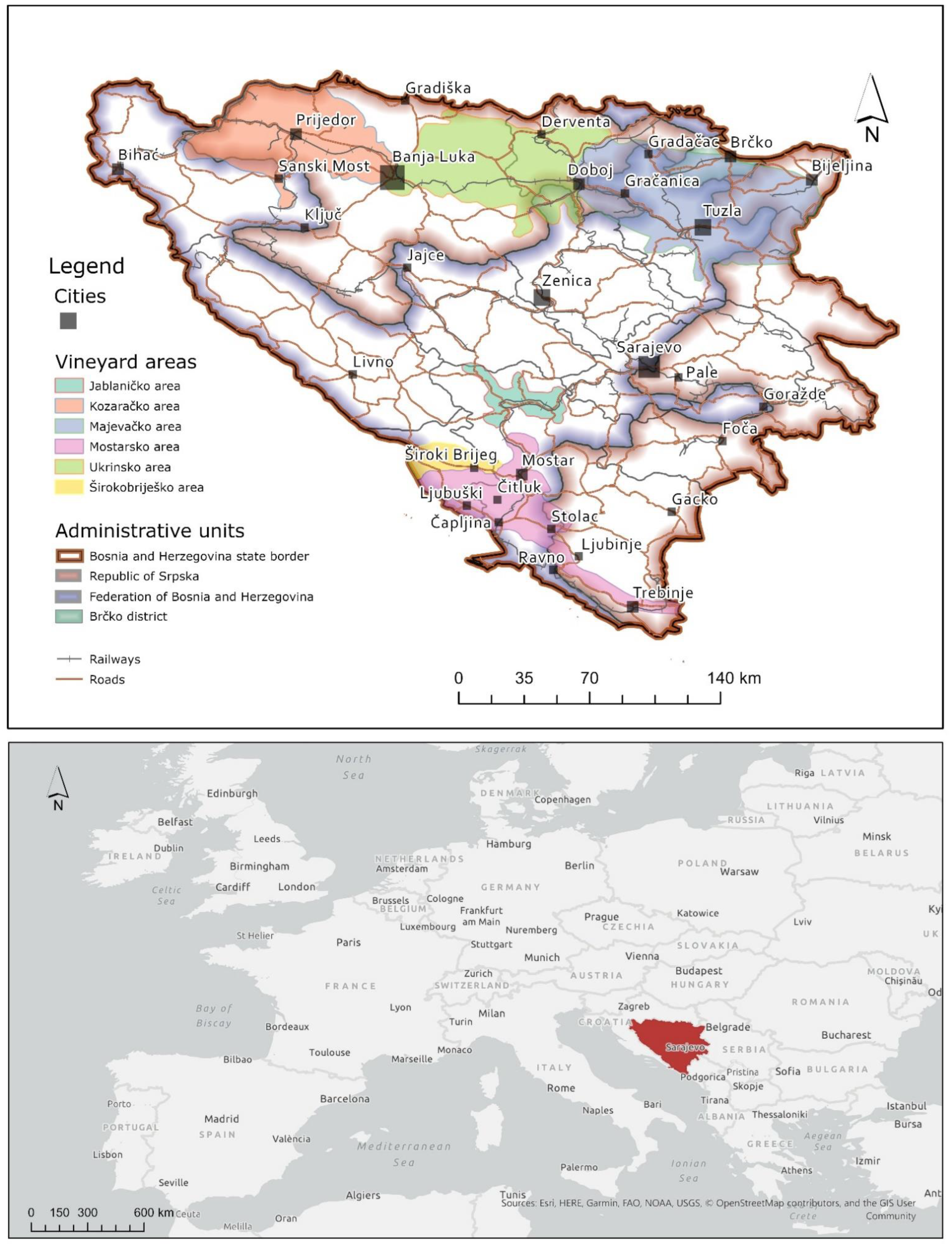

The Republic of Srpska is one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It covers the northern and eastern parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina with an area of 25,053 km

2 or 49% of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina (

Figure 1). It belongs to the group of continental areas, as it has no access to the sea, and is located at the contact point of two large natural geographical and socio-economic regional units—Pannonian and Mediterranean—and represents the link between the Pannonian and Adriatic basins.

Wine tourism and wine production in Bosnia and Herzegovina began developing increasingly only recently. Primarily due to the war activities on the territory of former Yugoslavia during the 1990s, viticulture and winemaking in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and thus in the Republic of Srpska, was underdeveloped and characterized by fragmentation of many small grape growers. As such, it has a local market character and does not contribute to developing the country’s international image and reputation [

10]. On the other hand, some essential preconditions for its development are already present. For example, the neighbouring countries of Croatia and Slovenia are third and fourth in the world in per capita wine consumption, and tourists from these countries are interested and eager to visit Bosnia and Herzegovina [

8]. To capitalize on these facts and be successfully included in the Wine Routes, the small wineries in the rural areas of the Republic of Srpska need to have adequate catering capacities, i.e., primarily tasting rooms within the wineries. An additional advantage would be to provide accommodation facilities, appropriate parking lots, signposts, etc. They need to have qualified and friendly staff who are well acquainted with grape varieties, wine tasting, and wine in general, as well as the natural values and cultural heritage of the region in which they are located [

11].

There are no official statistics on the number and size of agricultural holdings engaged in grape production in Bosnia and Herzegovina; however, an estimate was made based on data prepared by the Agency for Statistics. It is estimated that the number of grape-producing farms primarily for wine production is around 11,000, most of which are smaller producers, growing grapes for their own needs and the local market with variable prices.

According to the official estimate of the OIV (Organization Internationale de la Vigne et du Vine—International Organization of Vine and Wine), there were about 4752 hectares (ha) under vineyards in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2016 and 36,904 tons of fresh grapes were produced [

12].

According to the Republic of Srpska Institute of Statistics, the area under wine grapes in 2019 was 562 ha [

12]. In the same year, 3494 tons of grapes were produced, from which about 752 thousand litres of wine was made. The average yield per grapevine was 1.9 kg. A little over one-half (55%) of the produced wine is white while the rest is red, with rose wines being produced in very small quantities (less than 1%). Even though many old grape varieties have been abandoned in favour of well-known international varieties, analysis shows that current wine production focuses on high-quality wine categories made mostly from indigenous varieties such as Žilavka (white) and Blatina (red). These two varieties are ideal for growing in the local climate conditions and are also a part of the local tradition and cultural heritage. Žilavka has been grown in the region of Herzegovina for more than 600 years, being first mentioned in the 14th century. Due to the grape quality and its resistance to bunch rot (Botrytis cinerea Pers.), the Austro-Hungarians used this grape to produce a unique dessert wine of the Malaga type in the 19th century). In addition to its historical significance and tradition, the Žilavka grape is also of economic value since it accounts for most of the total wine production in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It ripens in the middle of the third period, a little earlier than Blatina. The wines from this variety are usually fresh and light-bodied with higher levels of acidity, distinctly mineral and greenish–yellow in colour, with a specific aroma that varies from herbal to floral notes. The other widely planted grape variety is Blatina. It is a red grape variety used for producing red wine. However, since it has functional female flowers, its cultivation is limited by the need for a pollinator. Therefore, it is increasingly being replaced by the Vranac grape variety. In the case of poor fertilization, it can give lower yields. It gives its best wines when cultivated in warmer and dryer regions. Blatina is a quality variety that often produces top quality wines from selected locations. It is often oak-aged, and wines from this variety are usually ruby red with deep colour intensity, medium to full-bodied with red and black fruit flavours and higher alcohol content.

Other important indigenous grape varieties planted include Krkošija, Bena, Trnjak, Dobrogostina, and Mala Blatina. Krkošija and Bena are white varieties usually used in Žilavka-based wine blends. Krkošija has higher sugar levels and produces wine with plenty of alcohol and extract but minimal aroma. It gives a poor-quality wine on its own, which is why it is often blended with Žilavka. Bena is more resistant than Žilavka, growing in harsher and dryer locations. It is a variety suitable for warmer regions with high resistance to powdery mildew. Its wine is of poor to medium quality with lower alcohol and sugar levels than Žilavka and Krkošija. Trnjak is considered an indigenous red variety in Herzegovina, although it is widespread in neighbouring Dalmatia, Imotski, Makarska, Vrgorac, and Opuzen, where it is best known as a Blatina pollinator. It is most suitable for dry and warm environments with red clay soil types (terra rossa). It can accumulate higher levels of sugar and acidity as well. Wines made from this variety have a dark ruby red colour, medium to full body, and a developed and characteristic varietal aroma of dark ripe fruit. Dobrogostina is a white variety best suitable for deep and moderately wet soils. It has between 16% and 19% of sugar, resulting in wines with 9–11% of alcohol and higher acidity. It ripens late and is often an accompanying variety to Bena and Krkošija in Žilavka-based wine blends. It is rarely used for varietal wines [

12].

Apart from these varieties, larger wine producers also make wine from international varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Chardonnay, Pinot blanc, Pinot noir, Cabernet Franc, and Sauvignon Blanc. In addition to classic varieties, interspecific hybrids of the latest generation are also grown, varieties more resistant to low winter temperatures and diseases, such as Pannonia, Morava, Lasta, Carmen, and others.

Although the domestic wine market has been improving in recent years, per capita, wine consumption remains low compared to the EU. According to OIV data, consumption per capita in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2002 amounted to only 2 L of wine, while in 2016, it almost doubled to 3.6 L.

The achieved level of wine exports from Bosnia and Herzegovina is about KM 7 million, and its most important market is Croatia, followed by Serbia and Germany. The value of wine imports is many times higher than exports and reaches KM 30 million. The imported wine comes mostly from Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, and Slovenia.

The main goal of this paper is to present the current state and potential of wine tourism in the Republic of Srpska with a special focus on its wineries and their efforts to attract wine tourists today and in future.

2. Literature Review

The origins of wine tourism go back to the 19th century, when wine-themed trips become popular. Increasingly, tourist offers included vineyards and winery visits in many European countries, where wine tourism today is an essential part of the overall tourist offer. Most of these countries, such as Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, and Germany, have a long winemaking tradition and are some of the most attractive wine tourism destinations worldwide [

13,

14].

There have been many definitions of wine tourism in the last decade, most focusing on visitor experience and motivation for visiting a wine region or a winery. Hall and Macionis [

15] defined wine tourism as “visitation to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals and wine shows for which grape wine tasting and experiencing the attributes of a grape wine region are the prime motivating factors for visitors”. According to Williams [

16], wine tourism involves more than just visiting wineries and purchasing wine: it is the culmination of several unique experiences created by the ambience, atmosphere, surrounding environment, regional culture, local cuisine, and wine with its intrinsic characteristics (grapes, techniques, and characteristics). Therefore, a visit to a winery is a holistic experience [

7] that includes a search for authenticity [

17], the cultural and historical context of the wine region [

18], an aesthetic appreciation of the natural environment, the winery, and its cellar door [

17], a sense of connection with the winery [

19], the production methods [

20], and a search for education and diversity [

21]. Bruwer and Alant [

22] expand this notion further by portraying wine tourism as a journey with the purpose of experiencing wineries, wine regions, and their connections to a particular lifestyle, encompassing both service provision and destination marketing. Such a hedonistic experience can only be achieved if the wine-scape is prepared to meet the needs of its guests [

22]. Therefore, creating enogastronomic experiences implies that winemakers in the region purposefully use their services as a stage and its products as props to involve tourists individually and create conditions for a memorable event [

23].

Wine routes have been significant tourism products in many European countries (France, Germany, Spain, Italy) during the last century. One of the earliest routes of this type was established in Germany during the 1920s in the Rhine Valley wine region. Their popularity increased considerably after the 1970s in Western Europe and during the last decade in the Eastern European countries, when winemakers and winery owners recognized the benefits of opening their wineries to visitors and collaborating with accommodation and service industry (restaurant) owners, local, regional, and even national tourism organizations and groups [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Today, wine routes are often complex tourism products offering winery visits and wine tastings enriched by including other tourist activities during the trip. They are often combined with cultural events or visits to natural and cultural heritage sites along the wine route. This model often works the other way around when visiting wineries, and attending wine tastings serves as a complementary activity during a trip to the desired destination. According to López-Guzmán et al. [

29], the motivation of the wine tourists on the Spanish Sherry Wine Route lies in the relationship between food and wine and is the main reason for their travel. Tourists seek new experiences beyond the merely visual and enhance other senses. Wine tourism can satisfy this need through wine tastings. Additionally, wine routes can help in the economic revival of underdeveloped regions. Such examples can be found in Moldova and Romania (Transylvania), where wine tours are an important part of the local economy, providing jobs to a significant number of people who would otherwise be without income [

5,

30,

31].

2.1. History of Viticulture and Winemaking in the Republic of Srpska

Until the arrival of the Greeks and the establishment of their colonies on the territory of the modern-day Republic of Srpska, the Illyrians who lived there did not possess knowledge about viticulture and winemaking. Illyrians drank beer and a type of mead [

32]. Grapevines most likely reached this area via Narona, a large port on the Neretva River. The Romans, who occupied the area at the end of the third century BC, contributed to the further expansion of grapevines and the improvement of viticulture. The wine was produced on estates that belonged to former Roman soldiers and on the larger estates, the so-called rustic villas (villae rusticae). Such estates existed in Panik near Bileća and Bihovo near Trebinje [

33]. Cultivation of vines from Dalmatia spread to the territory of today’s southern part of the Republic of Srpska through the valley of Trebišnjica and came to the north a little later along the Danube-Sava-Drava interfluve from north to south or west to east, and from south to north with the expansion of the Roman Empire [

34]. Posavina and Semberija were also wine-growing areas in ancient times, although the vines came there later than in Herzegovina. The Celts who inhabited these areas before the Roman conquests were familiar with grapevines.

After the arrival of the Slavs during the seventh and eighth centuries, the development of viticulture continued, with the clergy having a unique role after the baptism of Slavic settlers. There is considerable evidence of the presence of viticulture in the Middle Ages in Hum (Herzegovina), from where it spread to Foča, Goražde, Višegrad and other places where viticulture was developed in the pre-Ottoman era. Viticulture and winemaking are also mentioned in several charters from the Middle Ages, the charter of Prince Miroslav at the end of the 12th century, Juraj Vojislavić from 1434, and, perhaps most important, the charter of King Tvrtko I Kotromanić. This charter and coat of arms are still used today as a trademark of Herzegovinian wines.

When the Ottomans occupied this area in the second half of the 15th century, they found well-developed viticulture. Viticulture was mainly practised by Christians who paid taxes on the production of grape juice (must). Muslims who grew vines paid taxes on the area of the vineyard as they did not produce wine but consumed grapes or processed it into other products. Based on the data from the first census conducted by the Ottomans, vines were then grown in Nevesinje, Rogatica, Rudo, Čajniče, Foča and Goražde. Today there are no traces of viticulture in these places. The Banja Luka area (the lower course of the Vrbas River) was also a wine-growing region in the Middle Ages and during the Turkish period. Although it is impossible to determine the amount of production from the Turkish census of the Bosnian Sandžak from 1604 [

35], it is evident that vines production was widespread in the Vrbas Valley.

The arrival of the Austro-Hungarian empire marked a turning point in agricultural production in this region. Modern measures of cultivation, pruning, and fertilization were introduced into a then primitive way of production. Fruit and vineyard land stations were immediately established in Gnojnice near Mostar, Lastva, Trebinje, and Derventa.

The station in Lastva near Trebinje was established in 1894 and intended to supply the southeastern region of Herzegovina, especially the area of Popovo polje. The total area of the station in Lastva was 38.4 ha, of which 29.1 ha were under grapevines and 4.8 ha under orchards. To train local winegrowers, several wine-growing families immigrated from Hungary and trained local workers under the leadership of the station manager. Many local winegrowers were trained in this way. An essential part of the stations’ operations were varietal trials, especially those involving indigenous varieties. At that time, the most important wine varieties of Herzegovina (Žilavka, Bena, Krkošija, Dobrogostina, Pošip white and red, and Blatina) were described. The station in Lastva did not continue its viticultural function after the First World War. In 1919, the provincial government distributed the area of the former wine-growing station to private individuals. During the phylloxera invasion in the Trebinje region (1920–1930), the vineyards of the former station were mostly destroyed. After the Second World War, the area of the former station belonged to the Agricultural Cooperative, which began the renewal of vineyards. In the late 1990s, most of the area of the former station was bought by the famous Trebinje winemaker Vukoje who planted about twenty hectares of vineyards, which remain in his possession today.

During the 1950s, a new era in viticulture began, and it lasts to this day. Modern viticulture based on plantation production began initially in agricultural cooperative vineyards. This was a time of socialist regulation of the production, the formation of large social or state-owned estates and accelerated investment in agriculture.

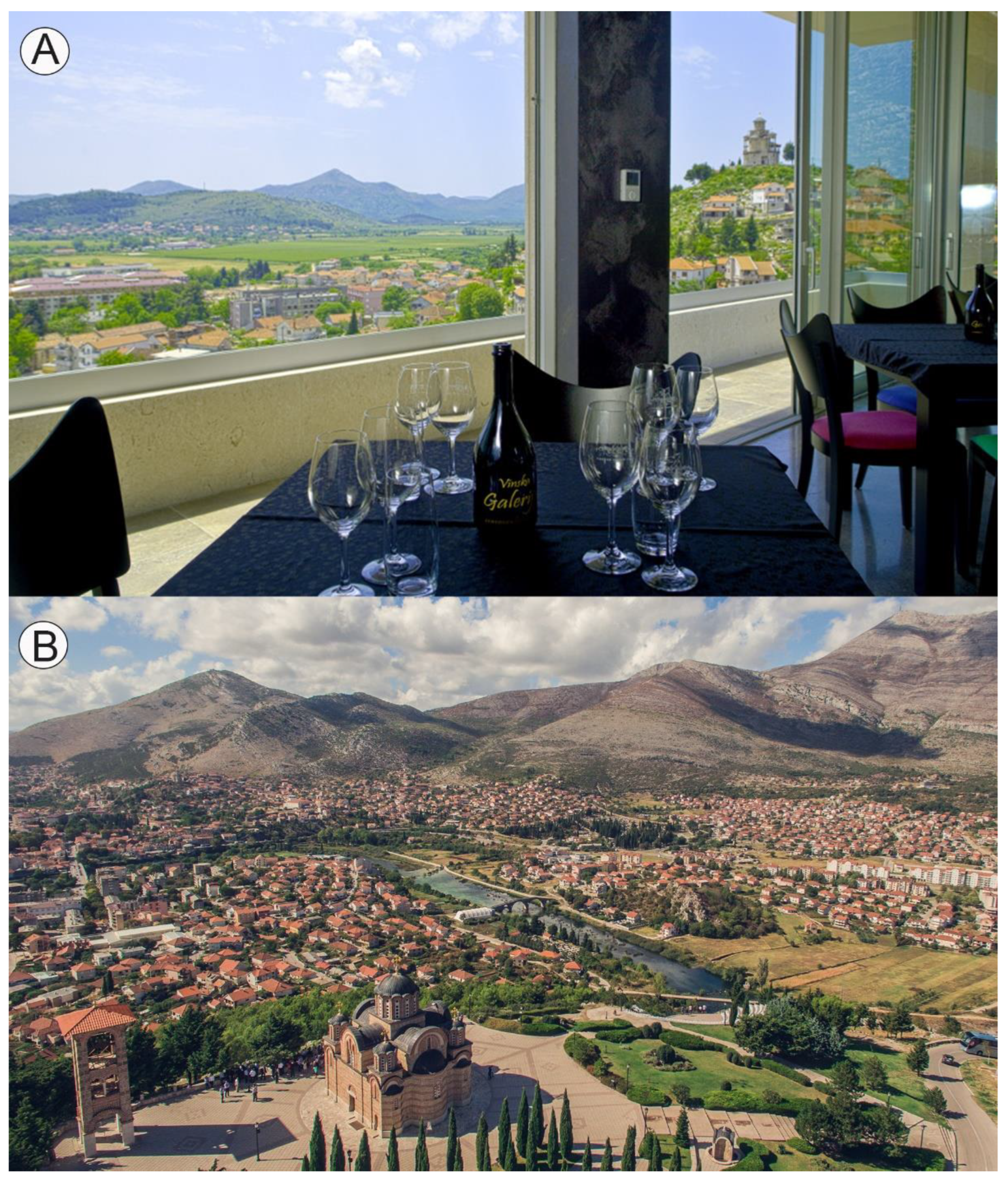

The war of the 1990s again led to the stagnation of viticulture in the Republic of Srpska. From the 2000s until today, the area under vineyards in the Republic of Srpska has gradually increased. Today, the production of grapes and wine as a traditional activity can be characterized only in the region of Eastern Herzegovina. The area of the municipality of Trebinje, with Popovo, Petrovo, and Mokri polje in the eastern part of Herzegovina, is the leading wine-growing area in the Republic of Srpska. The development of viticulture in the Kozarački, Ukrinski and Majevički vineyards is far below the average of that production on the territory of Herzegovina. The differences between these two regions reflect the climatic, pedological, and other specifics that significantly influence the production of grapes and wine.

2.2. Wine Regions and Vineyard Areas in the Republic of Srpska

Based on its natural, historical, and economic conditions, there are two wine-growing regions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Herzegovina and the Bosnia region.

The territory of the Republic of Srpska includes only a part of the Herzegovinian region, i.e., a part of the Mostar vineyards. The region of northern Bosnia has three vineyard areas: Kozaračko, Ukrinsko, and Majevičko (

Figure 1), which falls only partly on within the territory of the Republic of Srpska [

36].

Based on climatic elements, the region of Herzegovina is classified within the C3 zone. The region of Herzegovina is under the direct influence of the Adriatic Sea and mostly has the characteristics of Mediterranean climate. The terrain's significant features are the karst landscape and its terraced descent from the mountain peaks towards the sea. At certain times of the year, the bare karst has a visible impact on climate elements, especially temperatures. This area is represented by higher terrain and hills between which there are periodically flooded fields. The average annual temperature of this region ranges from 12.2 to 15.3 °C, while the average rainfall is approximately 1491 mm around Mostar (685 mm during the vegetation period). The annual cloud cover in Herzegovina is below five-tenths, while the annual value of relative humidity ranges from 62% to 73%.

Based on climate data, the region of northern Bosnia is classified within the C1 zone. This region is under the direct influence of the Central European Eastern Climate. The average annual rainfall is around 1000 mm (624 mm during the vegetation period). The distribution of rainfall satisfies and provides the necessary conditions for viticultural production. Relatively low average minimum temperatures impose the need to cover the vines with soil during winter. The average annual temperature in the region ranges from 10.1 to 10.9 °C. The annual cloud cover in the area ranges from 6.0 to 6.7/10, while the annual value of relative humidity ranges from 76% to 81%.

4. Results

Table 1 shows that the largest number of wineries (51.35%) is located in Trebinje (wine-growing region of Herzegovina), then Prnjavor and Laktaši (equal share of 10.81%), while the remaining 27.03% of wineries are located in six different municipalities/cities of the Republic of Srpska (Derventa, Kozarska Dubica, Novi Grad, Prijedor, Banja Luka, and Čelinac).

The most significant characteristics of the surveyed wineries are presented below. The survey data shows that most wineries have a family tradition. Most wineries were established in the 1980s and 1990s, but they have been renovated and modernized in the last decade (

Table 2).

From the data shown in

Table 2, it can be seen that all surveyed wineries are privately owned. They are most often registered as limited liability companies, independent companies, or agricultural holdings. More than a quarter have some of the food quality and safety management systems in place. When it comes to selected tourist indicators, it can be seen that more than 85% of wineries are open for visits; however, not all of them offer wine tastings as well. Almost all surveyed wineries offer the sale of wine at the cellar door. Only a small number of wineries offer accommodation services, and slightly less than a quarter have a website. This is one of the key issues thwarting further tourism development. Websites are needed as basic sources of information for potential tourists.

The average area under vineyards is 13.09 ha (

Table 3). Of the total number of respondents, 45.95% have vineyards that cover an area of more than 3 ha, 51.35% of respondents own vineyards on an area of 0.4 to 3 ha, while 2.7% of surveyed wineries do not have their own vineyard. Wineries that do not have their own vineyard and those with over 160 ha of vineyard areas significantly deviate from the majority of respondents, which resulted in a high value of the variation coefficient (277.60%).

The values of the coefficient of variation of 139.82 indicate a significant variation in the annual production of wine, which averaged 36,885.29 L, varying from 5000 to 250,000 L. The average grape yield was fairly equal. The capacity of the tasting room varied from 10 to 300 and averaged 80.96 people. Only 13.51% of respondents have their own bottling line, with an average daily capacity of 8320 bottles.

The number of workers employed in wineries and vineyards varied from 1 to 40 people, depending on harvest time. Employees are usually family members and seasonal workforce. About half of those surveyed in a winery or vineyard have an employed trained oenologist or agronomist. The survey shows that about 60% of respondents had no previous experience in the wine industry, while about 40% of respondents gained experience in Italy, California, Dalmatia, France, Serbia, and through family tradition. In a large number of wineries, younger household members are interested in continuing the family tradition.

The most widespread grape varieties in the Republic of Srpska are the indigenous varieties Žilavka (white wine variety) and Blatina (red wine variety). Of the introduced varieties, the most widespread variety is Vranac, followed by Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Italian Riesling, Tamjanika, Smederevka, etc. Based on the survey, it can be concluded that most wines are produced from the varieties Žilavka and Vranac, followed by Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay and Tamjanika. Depending on the needs of the market and the taste of the winery’s customers, different combinations are made during wine production. Varietal wines are the most common, and blends of different varieties can now be found on the market more often.

The survey further shows that there are about 60% of those for whom winemaking and wine tourism are not the primary activity. Constant engagement of oenologists in wine production is present in 21.62% of wineries, while 37.84% do not use their services. There are 37.84% of respondents who occasionally hire an oenologist, while the remaining 2.7% did not answer this question. Regarding wine tourism, 64.86% of wineries are open for tours, 67.57% are open for wine tasting and sale, 27.03% of wineries are open for food, catering, and similar services. The organization of events (meetings, weddings, special events) is offered by 24.32% of wineries, while accommodation services are offered by only 18.91% of wineries. The largest number of wineries, 70.27%, are open for visits throughout the year.

According to the survey, there are very few of those who have been formally educated to work in wine tourism. Those who did have some education often attended seminars or similar workshops. There are more wineries where individual groups of visitors come compared to the organized tours; however, according to the survey, the most, 56.76%, reported both individual and organized visits. Most wineries (67.57%) can receive visitors in their wineries and tasting rooms with capacities ranging from 10 to 200 seats.

As many as 75.68% of wineries do not have accommodation capacity. Most wineries are considering improving their visitor services and building accommodation facilities in the future. All the wineries are located within 40 km from urban areas (cities), where plenty of accommodation can be found until the wineries build their own facilities. The largest number of wineries, 70.27%, cooperate with travel agencies, tourist organizations, and organizers of wine events, while 29.73% of wineries do not cooperate. In this context, the cooperation with wine event organizers and tourist organizations is at the forefront, followed by the cooperation with travel agencies (40.54% of wineries are included in some tourist agency arrangements, while 59.46% of surveyed wineries are not included).

Most wineries (89.19%) do not keep accurate statistics on the number and origin of tourists. A free estimate of the number of visitors is between 50 to 20,000 visitors per year. According to these estimates, the number of foreign and domestic visitors is equal. Attendance at fairs to promote wineries is present with almost three-quarters of respondents. In addition to attending fairs, many wineries also promote their activities through their own brochures, brochures of tourist organizations, e-mails, internet presentations, the use of information boards, advertising in wine magazines, and advertising on television and radio (

Figure 2). Big wine fairs and similar events have proven to be one of the most important ways of promoting and reaching new wine and wine tourism markets. Given their international character, they attract many wine lovers who have a unique opportunity to taste wines that are often not sold in their own countries and get to know the winery and their products, which often leads to them visiting the winery in the near future. This is especially the case at wine events in the neighbouring countries (Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro). This way, the wineries are in direct contact with the potential consumers outside their domestic market. Given the current challenges in the wine and wine tourism sector, besides wine fairs, web presentations and social networks should have a much more significant role in the promotion ofpromoting wine and wine tourism in the Republic of Srpska. There are still a number of wineries that do not have a visible online presence, solid web presentations or social network profiles and pages. Seeing as this is not a significant investment, it could be rectified quickly and easily in the future.

The most common services that wineries offer to visitors are wine tasting and providing information about the winery. The vineyard tour and the cellar tour service are equally represented, and this service has been expanded to include a light snack. Other services offered by wineries include mainly the sale and tasting of local food, participation in the harvest, and an expert guide in a foreign language (

Figure 3).

Almost 60% of wineries plan to introduce innovations to improve their tourist offer; some through the opening of new accommodation facilities, others through the modernization and expansion of tasting rooms with a better gastronomical offer and the organization of different events.

One issue that the survey did not cover but was mentioned by the winemakers is their belief that the state does not provide enough supportive measures (primarily financial support and incentives) to develop and improve this type of tourism. Furthermore, winemakers in Eastern Herzegovina believe that a major obstacle to tourism development is poor traffic infrastructure in this region.

5. Discussion

Modern tourists are increasingly looking for authentic experiences, specific products, unique food and drinks of a particular region. One of the specific products is wine tourism, which embodies elements of culture in the way of life of people and their attitude towards wine and food [

37].

Wine tourism as a specific form of tourism is enriched through wine events. This form of tourism also has an educational dimension because it enables learning about grape varieties, wine production technologies, and geographical, ethnographical, and historical specifics of the given wine region. Wine tourism has become a key element in creating new and more complete, comprehensive tourist destinations. In offering tourists an experience of the culture and way of life unique to the specific region, wine tourism increases the attractiveness and overall value of that tourist destination. The development of wine tourism contributes to the positioning and recognition of a particular tourist area and creates a competitive advantage [

4].

Over the past few years, one of the more important concepts for wine travellers is captured by the French term terroir. It has become a significant motive for wine-related travel. Terroir refers to complex interactions between all physical elements—geology, soils, climate, geomorphology, and vegetation—that combine to create a particular ‘place’ where grapes are grown [

38]. The general assembly of the International organization of vine and wine (Resolution OIV/Viti 333/2010) defined terroir as a concept that refers to an area in which collective knowledge of the interactions between the identifiable physical and biological environment and applied vitivinicultural practices develops, providing distinctive characteristics for the products originating from this area. Terroir includes specific soil, topography, climate, landscape characteristics, and biodiversity features [

39,

40].

The growing presence of the term terroir throughout the wine world, with the help of media and other means of communication, has led to people no longer wanting just to try wines from specific regions at their homes. The more demanding wine tourists and wine lovers are no longer fully satisfied with pure wine tastings at wineries. Nowadays, most are already familiar with certain wines in advance because they have already tried them before. Regardless, the majority of wine tourists now wish to go one step further and hear a more detailed story of how their favourite wine was created and what influences shaped it, giving it all of those unique qualities, aromas and distinctive taste [

41]. Apart from the quality of production and the quality of the wines themselves, wine lovers and wine tourists expect something more from the wineries and their offers, and this is most often reflected in all the specifics of the terroir. Since the wines of the Republic of Srpska have already significantly improved in the last decade, the next step should be to incorporate the terroir concept into their wine tourism offers, thus creating a new, unique, and more satisfying experience for the more demanding wine tourists.

When it comes to the Republic of Srpska, wine tourism should become a vital part of the comprehensive tourist offer in the strategic concept of tourism development. The results of our research indicate that the Republic of Srpska has the potential for the development of wine tourism because it has the predispositions shared by some world-famous wine regions. Western and southern European countries such as France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, have recognized the potential of the small and medium-sized vineyards and wineries to produce high-quality wine and expand their portfolio by engaging in tourism activities. So today, they are the leading wine tourism destinations in Europe [

5].

The region of Herzegovina has a long tradition of growing vines and thus processing grapes into wine. Some of the wineries are more than 100 years old. As for the processing technology, some of them still nurture tradition and old methods, while in the last twenty years, the majority of wineries produce and store wines according to modern technological procedures. Survey research shows that wineries in the Republic of Srpska are not sufficiently educated about the benefits of wine tourism and that the offer is mainly based on the production and sale of wine. The research of Trišić et al. [

24] on wine tourism in Vojvodina also supports these claims.

Karagiannis & Metaxas [

42] state that in the Peloponnese region, Greece implemented specific measures, including improving product quality and quality education of winery staff that influenced the development of wine tourism in this region. Similar activities must be undertaken in the Republic of Srpska in the future.

The results of our research show that most wines are produced from the Žilavka grape variety and that consumers most often demand wine made from this grape. It is the best-known grape variety in the region, and as such, it has been established as a sort of wine brand for this region. It is adapted to the agroclimatic conditions of this region, and it fully expresses the terroir of this area. Wines made from these grapes are often fresh and light-bodied with pleasant acidity, but there are some that can benefit from a few extra years of ageing in the bottle. Since wine from indigenous grape varieties is highly valued by wine tourists as typical representatives of a certain region [

43], the Žilavka grape variety could be used to attract foreign visitors looking for authenticity when choosing wine destinations.

Another problem related to wine tourism in the Republic of Srpska is the lack of wine routes. Skuras & Vakrou [

44] state the importance and necessity of the existence of wine routes because, through them, tourists can visit almost all the outstanding sights of the region, combining gastronomy and wine tourism with a large number of activities. Some of these activities include cellar visits and wine tastings, which are globally the focal points of wine tourism.

Another study [

45] showed that one of the largest obstacles in the development of wine tourism is the lack of information regarding the services offered. The surveyed wineries in the Republic of Srpska have a low level of promotion via the Internet, and more than 50% of them do not have a website, nor do they cooperate with tour operators. This is one of the key issues that need to be addressed as soon as possible.

As stated in the research of Novo et al. [

6], an important fact that accelerates the development of wine tourism is that it must generate a production chain and values based on gastronomic and wine products. This enables connection with other cultural activities (festivals, wine tastings, exhibitions etc.) that, as a whole, lead to the rapid growth of the offer intended for different consumer segments. Therefore, combining wine-related activities with other tourist attractions is necessary for successful wine tourism development.

The same authors state that local authorities and the private sector encourage marketing and promotional strategies in the mass media and social networks to position destinations and regions of Mexico as gastronomic destinations, and especially as wine producers. The advantage, among other aspects, is the prestige of Mexican cuisine, which has been considered an intangible cultural heritage of UNESCO since 2010 and is also considered a self-determined feature of Mexican culture, a product of its history and cultural diversity.

Additional comments from the surveyed winemakers show that winery owners are aware of the importance of a gastronomic offer, and those who do not currently have a gastronomic offer said that they plan to introduce it in the future offer of the winery. A study by Karagiannis and Metaxas [

42] states that the presence and incorporation of catering facilities in wine tourism are crucial as it improves the tourism experience and development. Wineries that offer this type of service are built or renovated in the 21st century following high standards. Our research shows there are very few wineries in the Republic of Srpska that offer accommodation services. Considering the conclusions made by Karagiannis and Metaxas, the wineries in the Republic of Srpska should enhance their offer and include catering and accommodation facilities if they wish to attract a more significant part of the wine tourism market segment. Additionally, guided tours should also be offered in foreign languages, especially English, as this service is currently unavailable in most of the wineries.

Well-known wine tourism destinations such as France, Spain, and Italy already attract a significant number of wine tourists. However, at new and less developed wine tourism destinations such as the Republic of Srpska, wineries need to develop new marketing tools to compete in the global wine tourism market. They need to find a way to meet the needs of modern-day wine tourists. Since most wineries in the Republic of Srpska are small, they have a comparative advantage over larger wineries; they can offer a more customized and personalized service because they can only receive smaller wine tourist groups. This type of personalized experience during visits often serves as an advantage for these smaller wineries since more and more wine tourists prefer this rather than visiting large wineries in large groups where the sense of personalized service is almost always lost. Therefore, wine tourism is better suited to smaller wineries because smaller groups of tourists feel better connected with their hosts during their visit. Consequently, they have a larger sense of gratitude which in turn results in increased wine sales.

This type of wine tourism offer has paved the way towards developing wine routes and a rise in wine tourism in general. In order to succeed and remain economically sustainable, smaller wineries in the Republic of Srpska need to collaborate. This is especially important in the case of promotional activities where joint work is necessary to promote the entire wine region (with all its wineries and other attractions as well) instead of each winery on its own. Some of these collaborative promotional activities include the creation of wine routes, the organization of various wine events, etc. Most winemakers should form networks for immediate tangible benefits like purchasing partnerships to achieve better economies of scale and resource efficiency, thus creating depth and interest in the tourist products of a wine region [

46]. There are also several intangible benefits like sharing knowledge about the wine and wine tourism industry and the overall rise in product visibility. This type of sharing can be crucial for sustainable wine tourism growth. According to Yuan et al. [

47], a wine tourism market is successful and sustainable through the loyalty of returning wine tourists and the ability to attract new tourists to the winery or wine region. This implies the availability of not only wine as the main product but also other services and products such as wine events, accommodation facilities, educated staff in wineries and, of course, other tourist attractions (cultural or natural) in the region. Most wine tourists do not visit wine regions solely because of wine or a particular winery. They usually look for a wide variety of tourist activities which is why it is essential that a wine region offers other tourist attractions and services as well. This is especially true at long-distance destinations and during more extended periods of stay. Besides these elements, sustainable wine tourism also requires consideration and balance of social and environmental factors. Wineries are usually located in rural areas, and they mostly rely on the support of the local community when it comes to the provision of different services to tourists visiting the wine region. However, the local community cannot always provide adequate staff or infrastructure to satisfy all wine tourists’ needs. Therefore, the proximity to urban areas can often play a crucial role in sustaining long-term viability [

42]. The advantage in the Republic of Srpska is that most of the wineries are near cities which makes them more accessible to tourists, but also provides a more diverse choice of employees from different sectors and with different levels of education and skills. Environmental factors related to wine tourism usually include soil degradation, water consumption and land use. These are some of the key issues that need to be addressed for sustainable wine tourism development. Some of the solutions for this are water conservation, the use of alternative energy sources, recyclable materials, bioclimatic construction, and the participation of wineries in sustainability agreements. These activities can be implemented in the Republic of Srpska through a comprehensive tourism plan linking the primary wine sector with tourism, thus combining the local products, the local community, natural values, culture and tradition into one unique product. In order to achieve all of the aforementioned, which would lead to sustainable wine tourism development in the Republic of Srpska, it is necessary to integrate wine tourism into the existing tourist offer through national strategic documents for tourism development. Existing EU programs and grants can be used to develop education programs and short education cycles for the wine and tourism sector in order to solve the current education deficit and lack of knowledge about modern development models, which would, in turn, ensure the sustainability of the currently almost invisible wine sector.

6. Conclusions

The results and conclusions can be summarized through a SWOT analysis (

Table 4). As it can be seen from

Table 4, there are many strengths and opportunities for wine tourism development in the Republic of Srpska. One of the biggest is undoubtedly the indigenous grape varieties. Contemporary wine tourists always seek to try new wines from indigenous varieties wherever they visit, and the Republic of Srpska can offer wine tourists several local varieties (both white and red). Additionally, some indigenous varieties (especially Žilavka and Blatina) can produce high-quality wines making them an even more important asset in the wine tourism offer. Therefore, these indigenous varieties should be treated as the key elements on which wine tourism should be developed in the future. Besides these, wines from well-known international grape varieties (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc) are also present, completing the overall wine tourism offer in the Republic of Srpska.

To further wine tourism in the Republic of Srpska, several weaknesses must be addressed. The total surface area under vineyards is currently too low. Therefore, many wine producers import grapes from Northern Macedonia and neighbouring wine countries. This, in turn, affects the full implementation of the laws and policies regarding winemaking and the geographical indication of wines. Additionally, the current political situation and lack of political support for winemakers, and wine tourism in general, pose a significant threat.

One of the ways to identify the state of wine tourism at a destination is to use Butler’s development model of the evolution of the tourist area, which, according to Pivac [

9], can be used to identify the characteristics of a tourist place and its evolutionary phase. Based on this tool, specific measures and activities can be implemented to further wine tourism development at a destination. Therefore, such a development model could be used to determine the evolutionary phase of wine tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and after the findings, to determine further action towards its improvement. Various events dedicated to wine can contribute to the attractiveness and quality of wine tourism. In this regard, it is necessary to try to improve and adequately promote existing events of this type and to organize new ones in the coming period. The significance of such events can be seen in the example of neighbouring Serbia and the wine tourism of Fruška Gora. Events such as the Karlovac Grape Harvest, Pudarski Dani, and InterFest, contribute significantly to the above because some have visits from more than 100,000 people [

13]. As wine tourism itself is multidimensional, it is necessary to identify all stakeholders such as farms, wineries, tourist destinations, private and public companies and associations, environmental NGOs, protected area management, cultural heritage institutions, government, and local units, and include them in the marketing planning and development process of the wine tourist destination [

11].

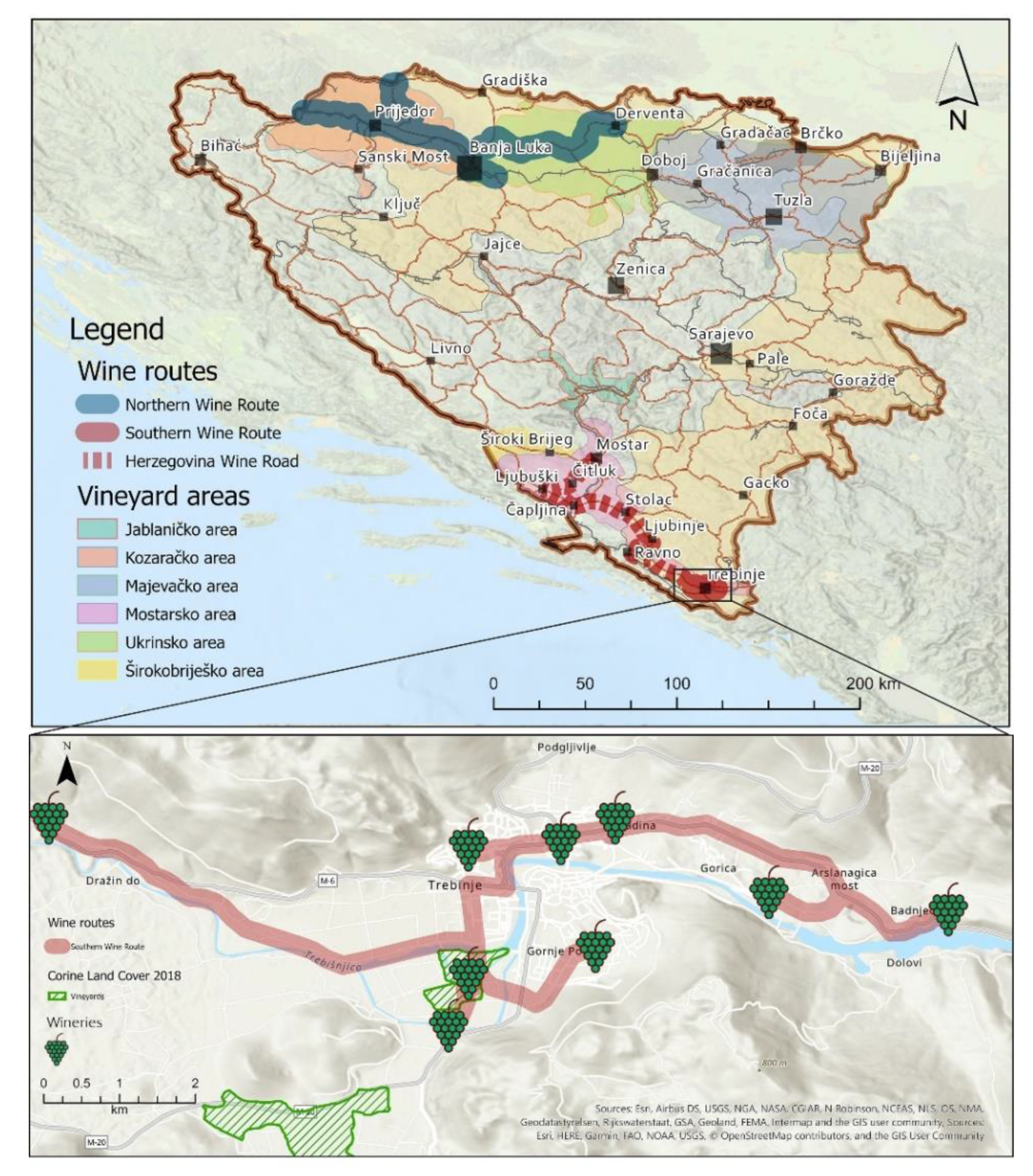

Currently, there are no wine roads in the Republic of Srpska. Wineries located in the southern part, in the region of Herzegovina, are part of the tourist product “Wine Roads of Herzegovina”, which stretches from Ljubuški in the west (Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) to Trebinje (The Republic of Srpska) in the east (

Figure 4). The creation of new wine routes in the Republic of Srpska would be an innovative solution, and the creation of wine routes would contribute to the branding of wine regions, increase revenues from wine sales and increase the number of tourists in the Republic of Srpska. The authors of the paper propose the creation of two wine routes (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) in the Republic of Srpska: Southern wine route of the Republic of Srpska (wineries in Trebinje) and the Northern Wine Route of the Republic of Srpska (wineries of the northern part of the entity). Creating these two wine routes in the Republic of Srpska would include numerous activities such as: building receptive capacities, marking the route, promotional activities, etc. These activities would have to be carried out not only by the government but by the wineries as well (tasting rooms, smaller accommodation facilities, promotional activities). Crucially, for new wine tourism regions seeking their place in the wine tourism market, several key issues need to be addressed before any major promotion and development can start. One of these critical elements is forming an organization that would provide dynamic leadership and drive the development forward. Wine route projects often struggle in the beginning to unite the wineries and convince them of the potential wine route benefits and collaboration towards one goal. Therefore, the organization must be efficient from the start, with a clear goal and focus towards achieving it whilst keeping the support and trust of the members (wineries). One of the main tasks of such an organization should be promotional activities of the wine route as a unique product instead of each winery only promoting itself. The creation of these two wine routes in Bosnia and Herzegovina would significantly improve the tourist offer of the Republic of Srpska and help winemakers, especially in rural areas, improve their income and wine sales through wine tourism.