Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications—A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the PReS Policy

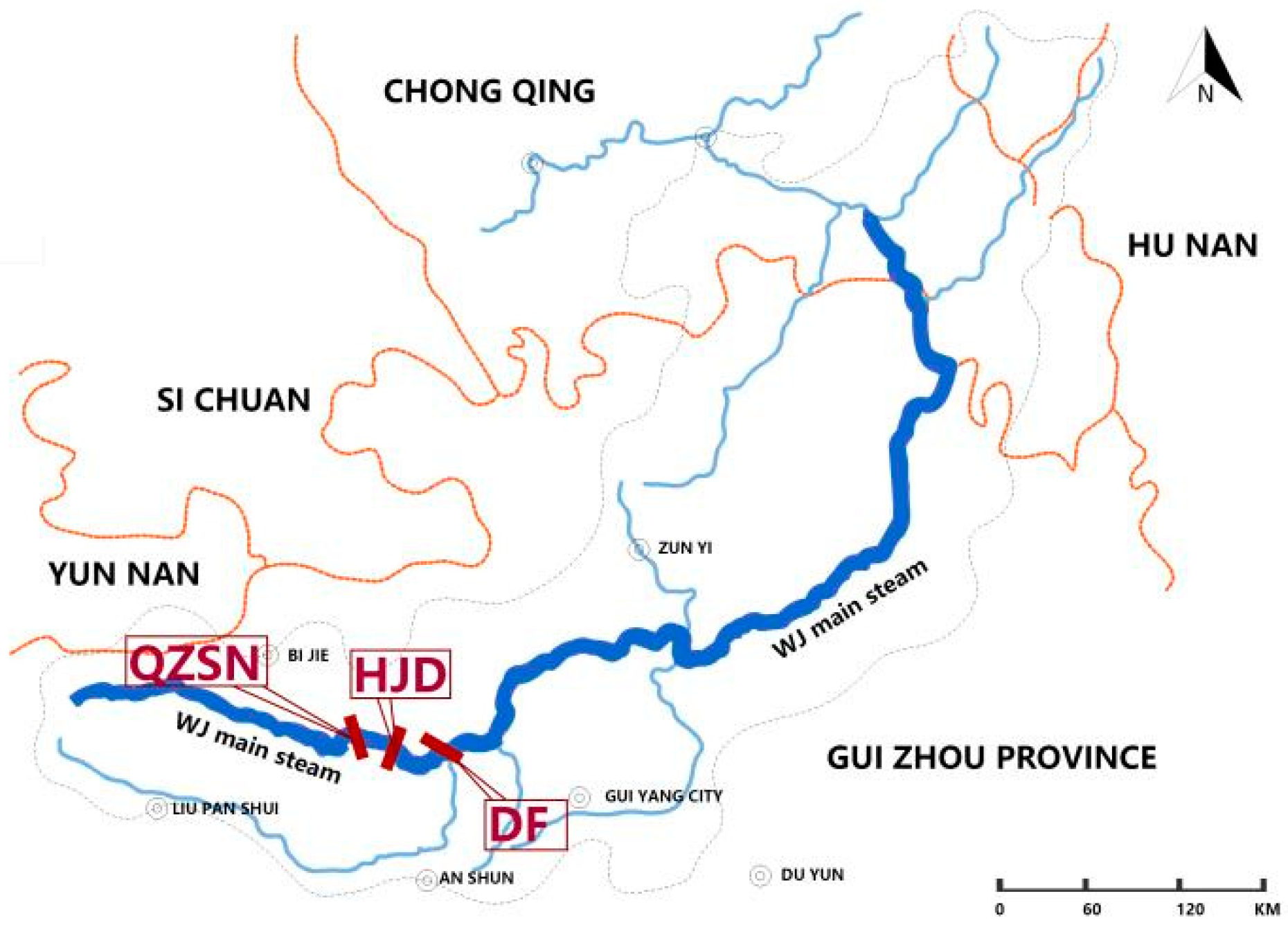

2.2. Description of Study Area

2.3. A Framework for Sustainable to Monitor Livelihood of Reservoir Resettlers

2.4. Indicators Selection for Livelihood Assessment

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

- (1)

- The rating scale method

- (2)

- 5 assets for livelihood pentagon

- (3)

- Livelihood capital

3. Results

3.1. The Impacts of Reservoir Resettlement

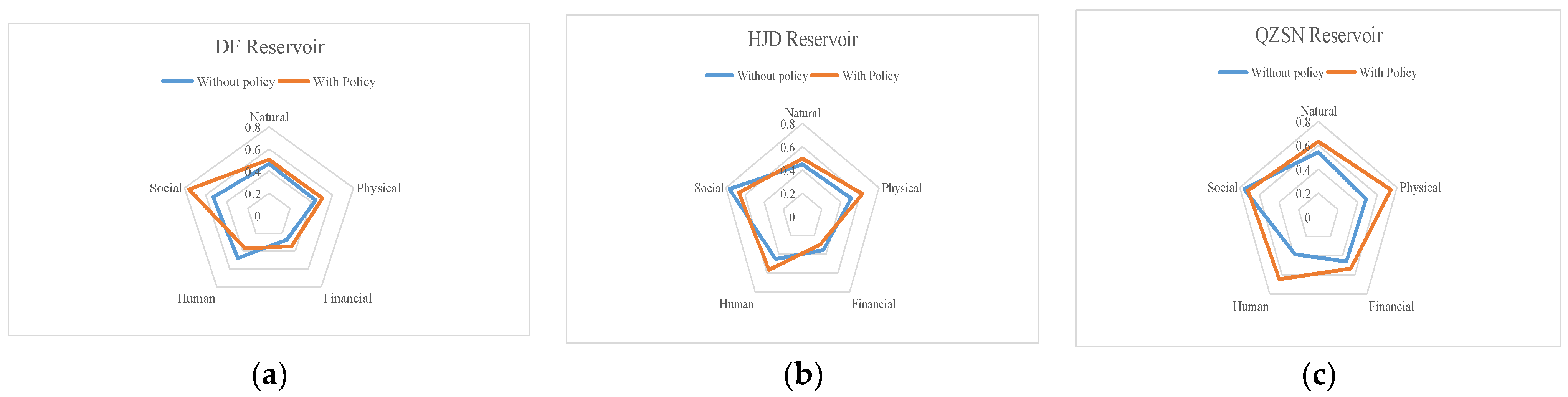

3.2. Comparison between with or without the Policy

3.3. The Time Response of the PReS Policy on Local Livelihood Capital

3.4. Impacts of the PReS Policy on Family Livelihood Diversity

3.4.1. Impacts of 600 RMB on Annual Family Income

3.4.2. Impacts of the PReS Policy on Livelihood Diversity via Development Project

4. Discussion

4.1. Relocation’s Impacts on the Livelihood Capital of Reservoir Resettlers

4.2. The Impetus behind the PReS Policy Implementation in Early Stage

4.3. Impacts of the PReS Policy in Time Line

4.4. Impacts of the PReS Policy on Livelihood Diversity

4.5. Trends of Resettlement Policies

4.6. A Dark Point of the PReS Policy—“The Phenomena of 40-to-50-Years-Old Resettler Group”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, G. Sustainable hydropower and public connition. China Three Gorges 2012, 12, 64–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhengang, S. Overview of general survey of basic conditions of water conservancy projects. China Water Resour. 2010, 11, 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. China’s dam construction level ranks first in the world. Build. Mater. Dev. Orientat. 2009, 3, 29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Duan, Z. Quantity and distribution of reservoir projects in China. China Water Resour. 2013, 7, 10–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. 70 Years of Land Acquisition and resettlement for Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects in China. Water Power 2020, 46, 8–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Z. Evolution of Land and Resettlement Laws in China: Setting New Standards. In Resettlement in Asian Countries: Legislation, Administration and Struggles for Rights; Zaman, M., Nair, R., Shi, G., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor Francis: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Shi, G. Causes and Cope in the remaining problems of reservoir resettlement. Water Econ. 2000, 3, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.; Chen, S.; Xun, H.; Fan, Z.; Chen, S. Exploration, Planning and Management of the Remaining Problems of Reservoirx Resettlement; Hohai University Press: Nanjing, China, 2000. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Q. Resettlement in China. In Impacts of Large Dams: A Global Assessment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, W. Power and powerlessness: Development projects and displacement of tribal. Soc. Action 1995, 41, 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Weser, M.; Guggenheim, S. Social Development in the World Bank: Essays in Honor of Michael Cernea; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; p. 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, A. Countering the Impoverishment Risk: The Case of the Rengali Dam Project Involuntary Displacement in the Dam Projects; Prachi Prakashan: New Delhi, India, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, H. The impoverishment risk model and its use as a planning tool. In Development Projects and Impoverishment Risk: Resettling Project-Affected People in India; Mathur, H.M., Marden, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 1998; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, M.; Khatun, H. Development Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Bangladesh: Case Studies and Practices; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, M.; Nair, R.; Shi, G. (Eds.) Resettlement in Asian Countries: Legislation, Administration and Struggles for Rights; Routledge/Taylor Francis: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M. Understanding and preventing impoverishment from displacement: Reflections on the state of knowledge. J. Refug. Stud. 1995, 8, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Involuntary Resettlement. OD 4.30. 1990. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- World Bank. Involuntary Resettlement, OP/BP 4.12. 2002. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- World Bank. Environment and Social Framework. 2018. Available online: http:// www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- State Council of PRC. The Regulation on Land Acquisition and Resettlement Compensation in Large and Medium-Scale Hydraulic and Hydropower Projects; Decree No. 74.1991; State Council of PRC: Beijing, China, 1991; Available online: http://gtj.yueyang.gov.cn/302400/30260/43314/content_1363066.html (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- GOI. The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act2013; Department of Land Resources, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G. Reservoir Resettlement System Planning Theory and Application; Hohai University Press: Nanjing, China, 1996; pp. 181–187. ISBN 7-5630-0802-0. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Hu, W. Comprehensive evaluation and monitoring of displaced persons standard of living and production. In Proceedings of the International Senior Seminar on Resettlement and Rehabilitation; NRCR, Ed.; Hohai University Press: Nanjing, China, 1995; pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). Handbook on Involuntary Resettlement: A Guide to Good Practice; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmsen, B.; Webber, M.; Duan, Y. Involuntary rural resettlement: Resources, strategies, and outcomes at the three Gorges Dam, China. J. Environ. Dev. 2011, 20, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G. Preliminary study on reservoir resettlement. Prog. Water Conserv. Hydropower Technol. 1999, 47–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Shi, G. Resettlement mode on rural resettlers as shareholder of hydropower projects. Yangtze River Basin Resour. Econ. 2008, 17, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, W.L.; Halmo, D.B. Resettling Displaced Communities: Applying the International Standard for Involuntary Resettlement; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M. Risks, safeguards, and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. In Risks and Reconstruction. Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees; Cernea, M., McDowell, C., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 11–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. Risks and Reconstruction-Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G. Comparing China’s and the World Bank’s resettlement policies over time: The ascent of the ‘resettlement with development’ paradigm. In Challenging the Prevailing Paradigm of Displacement and Resettlement: Risks, Impoverishment, Legacies, Solutions; Cernea, M.M., Maldonado, J.K., Eds.; Routledge: Abington, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Yu, F.; Wang, C. Social assessment and resettlement policies and practice in China: Contributions by Michael M Cernea to development in China. In Social Development in the World Bank; Koch Weser, M., Guggenheim, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B.; Adjartey, D.; van Hulten, A. Challenging the risks-based model of involuntary resettlement using evidence from the Bui Dam, Ghana. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 682–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, T.; Colson, E. For Prayer and Profit: The Ritual, Economic, and Social Importance of Beer in Gwembe District, Zambia 1950–1982; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Scudder, T. The Future of Large Dams: Dealing with Social, Environmental, Institutional and Political Costs; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, T.; Garcia-Downing, C. Routine and dissonant culture: A theory about the psycho-socio-cultural disruptions of involuntary displacement and ways to mitigate them without inflicting even more damage. In Development and Dispossession: The Anthropology of Displacement and Resettlement; Oliver-Smith, A., Ed.; School for Advanced Research Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2009; pp. 225–253. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303213123 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- De Wet, C. Why do things so often go wrong in resettlement projects. In Moving People in Ethiopia: Development, Displacement and the State; Pankhurst, M., Pguet, F., Eds.; James Currey: Woodbridge, ON, Canada, 2009; pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Shi, G. A discussion on the benefit-sharing mechanisms and methods for resettlement system. Water Conserv. Econ. 1995, 12, 58–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Chen, S.; Yuan, R.; Hu, W. Method in Analysis and Assessment of Living and Livelihoods Standard of Reservoir Resettlement. Water Conserv. Xuebao 1996, 62, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Shi, G. Land Asset Securitization Resettlement Model for Rural Resettlars Induced by Hydropower Development Project China; Social Science Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 34–205. ISBN 978-7-5097-3555-8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Owen, J.; Kemp, D.; Shi, G. An applied framework for assessing the relative deprivation of dam-affected communities. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Chen, S.; Xing, H.; Xun, H. China Resettlement Policy and Practice; Ningxia People Press: Yinchuan, China, 2001. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.; Mathur, H. Can Compensation Prevent Impoverishment? Reforming Resettlement through Investments (OUP Catalogue); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; McDonald, B. From compensation to development: The application and progress of RwD in China. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 4, 317–356. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M. Compensation and benefit sharing: Why resettlement policies and practices must be reformed. Water Sci. Eng. 2008, 1, 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, D. Advantages and obstacles to retro-fitting benefit: Sharing after development-induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Shi, G.; Qiao, X.; Zeng, X. Hydropower resettlement mechanism based on the benefifit sharing perspective. Water Conserv. Hydropower Technol. 2007, 38, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Koranteng, R.; Shi, G. Aalyzing the relevance of VRA resettlement trust fund as a benefit sharing mechanism. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, S.; Van Wicklin, W., III; Koenig, D.; Owen, J.; de Wet, C.; Kabra, A. Risk and value in benefit-sharing with displaced people: Looking back 40 years, anticipating the future. Soc. Chang. 2020, 50, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shi, G.; Li, B.; Fischer, T.; Zhang, R.; Yan, D.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Q.; Sun, Z. Skills’ sets and shared benefits: Perceptions of resettled people from the Yangtze-Huai River Diversion Project in China. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Owen, J.; Shi, G. Land for equity? A benefit distribution model for mining induced displacement and resettlement. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuefang, D.; Ali, S.; Bilal, H. Reforming Benefit-Sharing Mechanisms for Displaced Populations: Evidence from the Ghazi Barotha Hydropower Project, Pakistan. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 24, 3511–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Lyu, Q.; Shangguan, Z.; Jiang, T. Facing Climate Change: What Drives Internal Migration Decisions in the Karst Rocky Regions of Southwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saychai, S.; Shi, G.; Yu, Q. Resettlement Policies and Implementation Management: A Case of Hydropower Resettlement Management in Laos. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Shi, G.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Resettlement for the Danjiangkou dam heightening project in China: Planning, implementation and effects. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Shi, G. Policy and implementation of land-based resettlement in China (1949–2014). Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Shi, G. Stakeholder Participation in Rural Land Acquisition in China: A Case Study of the Resettlement decision-Making Process. In Making a Difference? Social Assessment Policy and Praxis and its Emergence in China; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Lei, Y. Constructing the Participation Mechanism of Reservoir Resettlement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shi, G.; Zhou, X. To move or not to move: How farmers now living in flood storage areas of China decide whether to move out or to stay put. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e312609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Shi, G.; Zhang, R. Social stability risk assessment: Status, trends and prospects—A case of land acquisition and resettlement in the hydropower sector. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shi, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Ahmad, S.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Q. Social impact assessment of investment activities in the China–Pakistan economic corridor. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2018, 36, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Andam, F.; Shi, G. Environmental and social risk evaluation of oversea investment under the China-Pakistan economic corridor. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. Research on Problems and Countermeasures for Urbanization of Reservoir Resettlement in Guizhou Province. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1065–1069, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Discussion on joint stock resettlement of water conservancy and hydropower projects. People’s Yangtze River 2008, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Comprehensive Evaluation of Implementation Effect on Later-Period Supportive Policy of Reservoir Resettlement Based on ANFIS. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 912–914, 1874–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Evaluating Chinese policy on post-resettlement support for dam-induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T.E.; Shi, G.; Zaman, M.; Garcia-Downing, C. Improving Post-Relocation Support for People Resettled by Infrastructure Development. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R. Involuntary Resettlement in Development Projects: Policy Guidelines in World Bank-Financed Projectsby Michael, M. Cernea. Am. Anthropol. 1990, 92, 806–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T. ’Mitigating social impoverishment when people are involuntarily displaced’. In Understanding Impoverishment: The Consequences of Development-Induced Displacement; McDowell, C., Ed.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, C.; Haan, A. Migration and Sustainable Livelihoods: A Critical Review of the Literature; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, S. Sustainable Livelihood Framework: Monitoring and Evaluation. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2021, 8, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. The Sustainable Development Assessment of Reservoir Resettlement Based on a BP Neural Network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. Wujiang River Basin Research; China Science and Technology Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Basic Information of Wujiang Waterway (Guizhou Section). Wujiang Waterway Administration Bureau of Guizhou Province. 24 July 2015. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B9%8C%E6%B1%9F/4733?fr=aladdin (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Historical Changes of Wujiang River. Colorful Guizhou Network. 15 June 2017. Available online: https://zhidao.baidu.com/question/1833812312094464420.html (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Wujiang Gallery. Colorful Guizhou Network. 18 December 2014. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1706968988913570861wfr=spiderfor=pc (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- XiaoCong, H.; Lisheng, Z.; Lingzhi, Y. Study on flood control operation problems and Countermeasures in Wujiang River Basin. People’s Yangtze River 2018, 49, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, K. Hydrological characteristics of the Wujiang River basin. Hydrology 1999, 19, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shaoliang, D. Building green hydropower. China Electr. Power Enterp. Manag. 2008, 1, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Junli, W.; Ying, G. Dynamic control analysis of flood limit water level of Dongfeng reservoir. Huazhong Electr. Power 2006, 41–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.; Sayer, J.; Frost, R.; Vermeulen, S.; Ruiz, P.; Cunningham, A.; Prabhu, R. Assessing the performance of natural resource systems. Conserv. Ecol. 2001, 5, 22. Available online: http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art22/ (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Carney, D. Sustainable livelihoods Approaches: Progress and possibilities for change. In Department for International Development; DFID: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C. Local livelihood under different governances of tourism development in China—A case study of Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Kong, L. Stakeholder analysis and ownership rights realization of hydropower development enterprises. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2008, 1, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Shi, G.; Wang, H. Study on Urbanization Resettlement for Rural Displaced Persons of Reservoir Project; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jian, H.U.; Xi, Y.E. Discussion on the Confirming Method of Line-outside Extended Relocation of Population in the Construction of Large and Medium-sized Water Resources and Hydropower Projects. Water Power 2015, 41, 19–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Shang, K. Land-asset-securitization: An innovative appreach to distingtuish between benefit-sharing and compensation in hydro-power development. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. Policy Innovation of Reservoir Resettlement under Urban-Rural Integration; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 85–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Shi, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H. Can China’s reservoir resettlement promote urbanization? Case Study 2015, 35, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Hao, H.; Hu, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Livelihood Diversification of Farm Households and Its Impact on Cultivated Land Utilization in Agro-pastoral Ecologically-vulnerable Areas in the Northern China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J. Discussions on the compensation principles and support policies of the development resettlement of Three Gorges Project. Water Power 2001, 167, 65–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Introduction of Guizhou Ecological Migration Bureau. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E8%B4%B5%E5%B7%9E%E7%9C%81%E7%94%9F%E6%80%81%E7%A7%BB%E6%B0%91%E5%B1%80/23120784?fr=aladdin (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- The Report on Listing Ceremony of Guizhou Ecological Migration Bureau. Available online: http://stymj.guizhou.gov.cn/ZWGK/ZDGK/GZYW/TPXW/201911/t20191125_17026330.html (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Bin, C.; Long, Z. Global migration governance and China’s role from the perspective of “community with a shared future for mankind”. J. Renmin Univ. China 2019, 33, 83–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gizaw, S. Resettlement Revisited: The Post-Resettlement Assessment in Biftu Jalala Resettlement Site. Ethiop. J. Bus. Econ. 2015, 3, 22–57. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, K.; Bai, L.; Peng, X. Research on changes of land-use in different scale in karst mountain. Carsologica Sin. 2005, 89, 949–950. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yangbing, L.; Ruiling, L.I. Karst rocky desertification: Formation background, evolution and comprehensive taming. Quat. Sci. 2003, 23, 657–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, G. Infrastructure Investment and Regional Economic Growth: Evidence from Yangtze River Economic Zone. Land 2021, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, K.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood Capital and Land Transfer of Different Types of Farmers: Evidence from Panel Data in Sichuan Province. China Land 2021, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, S. Does poverty-alleviation-based industry development improve farmers’ livelihood capital? J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Post-Resettlement Support Policies, Psychological Factors, and Farmers’ Homestead Exit Intention and Behavior. Land 2022, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleman, R.; Hunter, L. Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: Insights from analogues. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, K.; Chang, C. Everyday crises: Marginal society livelihood vulnerability and adaptability to hazards. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2013, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etea, B.; Zhou, D.; Abebe, K.; Sedebo, D.A. Is income diversification a means of survival or accumulation? Evidence from rural and semi-urban households in Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. A Multidiscip. Approach Theory Pract. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 22, 5751–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; An-Vo, D.; Cockfield, G.; Mushtaq, S. Assessing Livelihood Vulnerability of Minority Ethnic Groups to Climate Change: A Case Study from the Northwest Mountainous Regions of Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Capital-Asset | Principle Description | Criterion for Individual Principles | Indicators | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Assets | Quantity and quality of natural resources for future use are maintained. | -Land assets is improved or not -Water assets is improved or not | Land Resources N1 Arable land area N2 Water resources N3 Forest resources N4 | SN = (Ni1 + Ni2 + Ni3 + Ni4)/4 |

| Physical Assets | Physical capital is maintained or improved | -House physical condition is improved or not -Infrastructure is improved or not | Room decoration P1 Room area P2 Infrastructure level. P3 | SP = (Pi1 + Pi2 + Pi3)/3 |

| Financial Assets | Financing ability is improved equitably | -Financing ability is improved or not -Family revenue is improved or not | Financing channels F1 Family income F2 | SF = (Fi1 + Fi2)/2 |

| Human Assets | Ability to win added value is improved | -Education, work skill is improved or not | Education levels H1 Professional training H2 | SH = (Hi1 + Hi2)/2 |

| Social Assets | Social reciprocity is maintained within local systems | -Trust towards other social members -Emergency or economic shocks is buffered by social reciprocity | Kinship S1 Leader’s supports S2 | SS = (Si1 + Si2)/2 |

| Livelihood Capital | 5th Year | 10th Year | 15th Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | 8.46% | 41.95% | 21.48% |

| Physical | 59.56% | 94.23% | 110.76% |

| Financial | 27.31% | 50.18% | 62.26% |

| Human | −23.12% | 18.55% | 69.67% |

| Social | 43.26% | 60.24% | 75.59% |

| Total livelihood capital | 8.59% | 35.33% | 48.94% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Shi, G.; Dong, Y. Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications—A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052488

Xu Y, Shi G, Dong Y. Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications—A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052488

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yuangang, Guoqing Shi, and Yingping Dong. 2022. "Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications—A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052488