Analysis of the Vulnerability and Resilience of the Tourism Supply Chain under the Uncertain Environment of COVID-19: Case Study Based on Lijiang

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Supply Chain

2.2. Supply Chain Resilience

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Acquisition

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Result

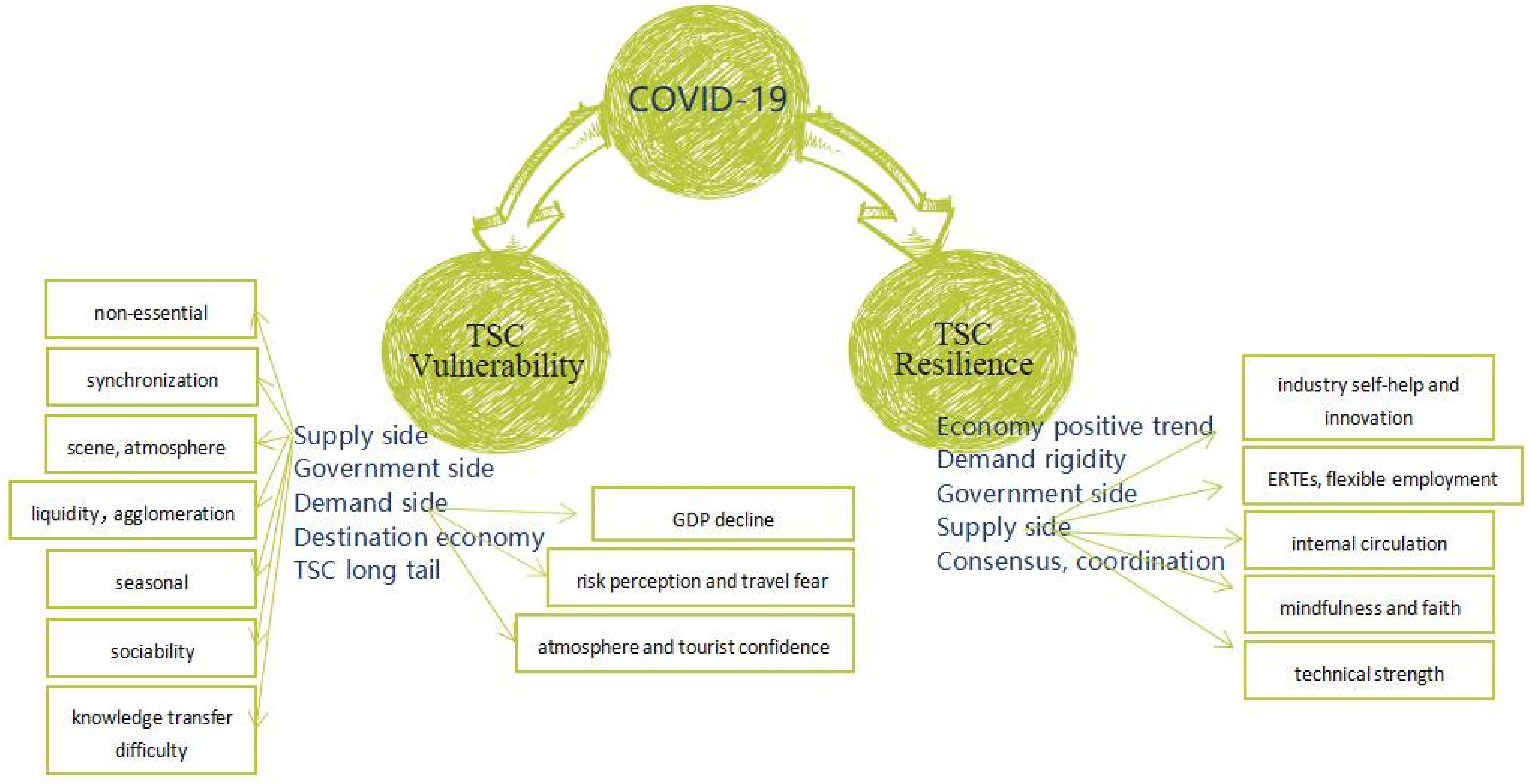

4.1. TSC Vulnerability

4.1.1. Supply Side of the TSC

- (1)

- The service nature of tourism industry

- (2)

- Unique attributes of Tourism

- (3)

- Stakeholders

4.1.2. Demand Side of the TSC

- (1)

- GDP Decline

- (2)

- Tourists’ risk perception and travel fear

- (3)

- Destination atmosphere and tourist confidence

4.1.3. Government Side

4.1.4. Destination Industrial Structure

4.1.5. Extension and Long Tail of Supply Chain

4.2. TSC Resilience

4.2.1. Tourism Economic Environment

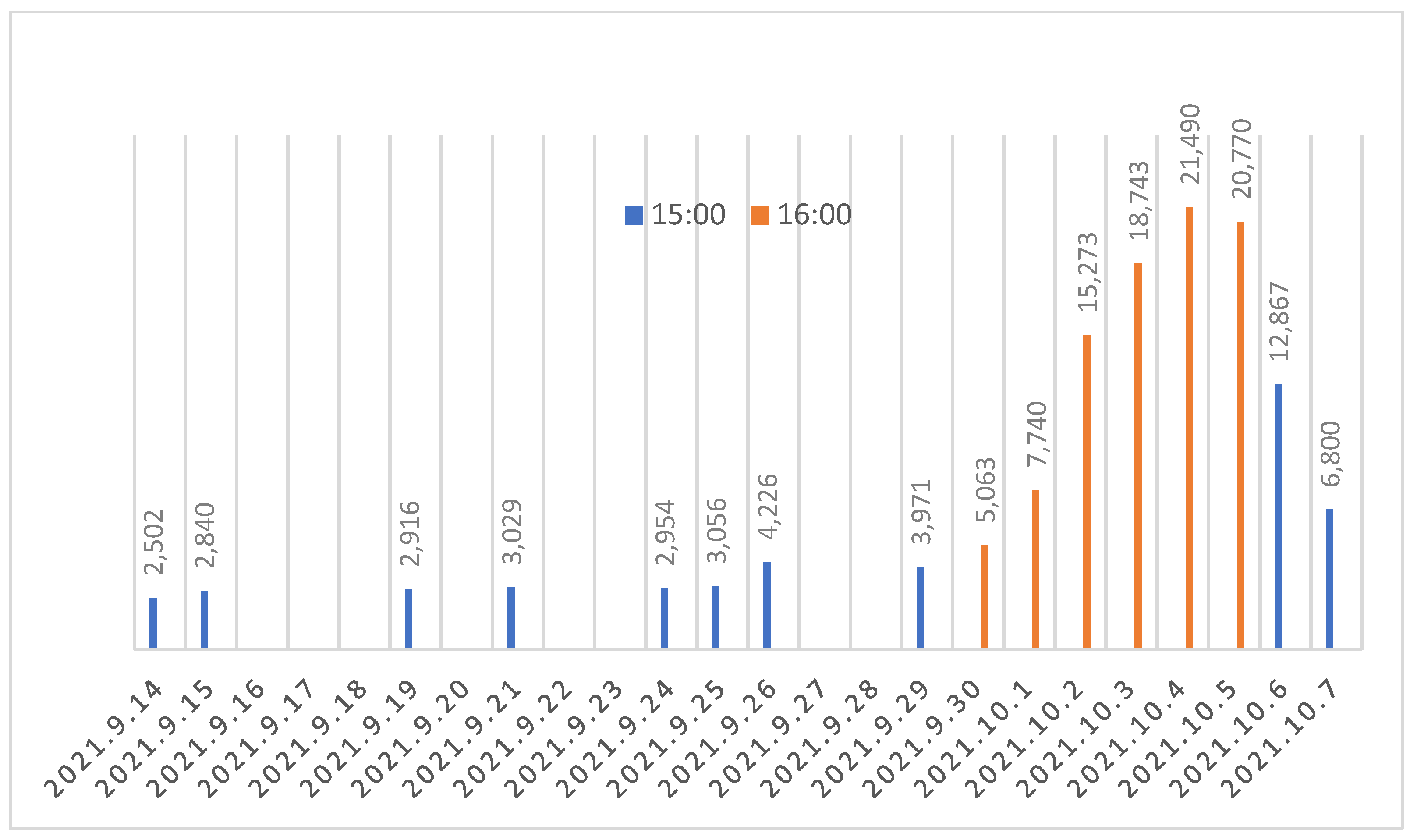

4.2.2. Tourism Demand Side: Tourism Demand “Rigidity”

4.2.3. Government Organizational Measures

4.2.4. Tourism Supply Side

- (1)

- Industry Self-Rescue and Innovation

- (2)

- Short-Term Work Program and Flexible Temporary Employment

- (3)

- Circulation Capability of Closed-Loop Supply Chain in Local Market

- (4)

- Mindfulness and Confidence of Tourism Practitioners

- (5)

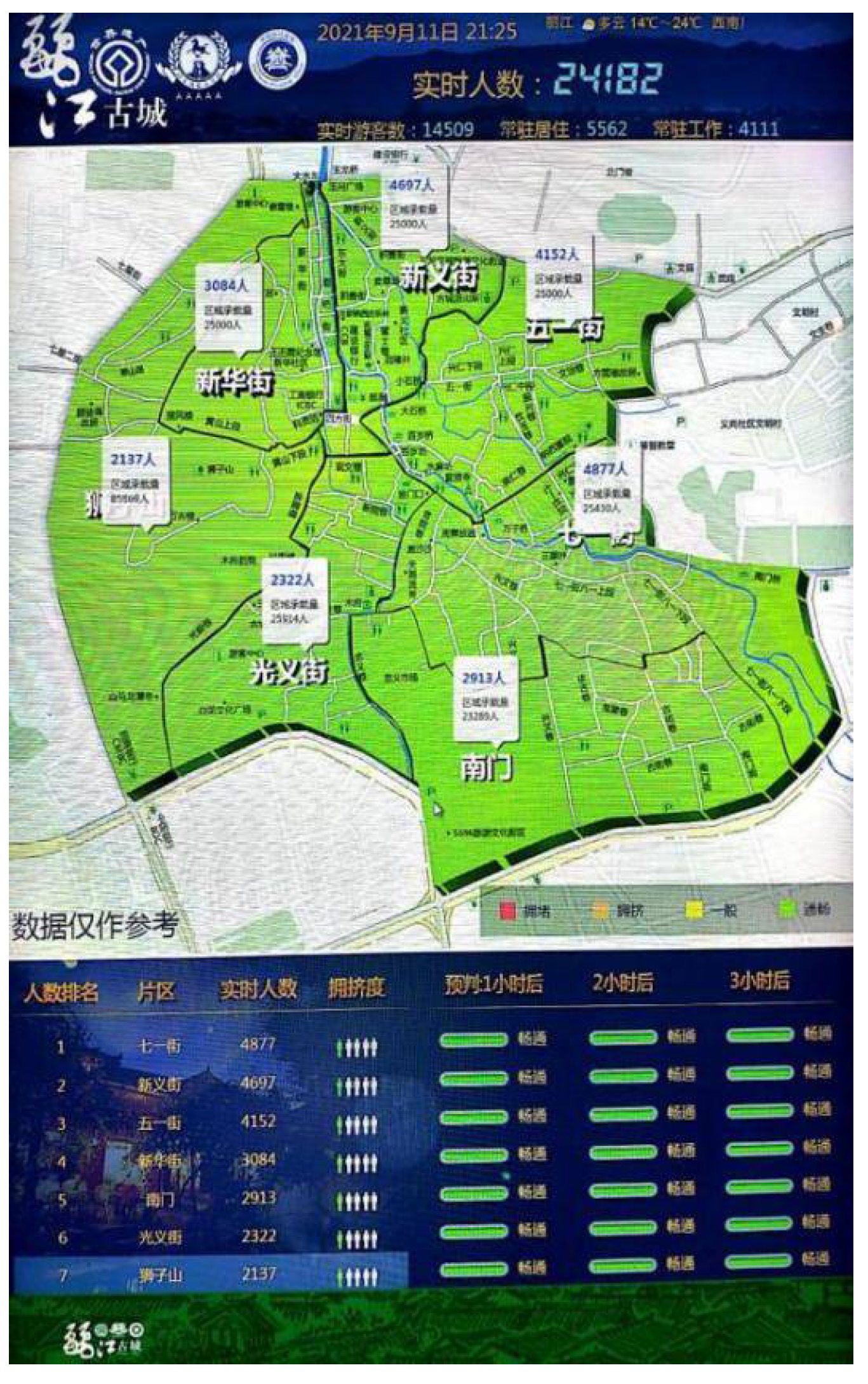

- Technical Power

4.2.5. Consensus and Coordination of Market Participants

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- Under COVID-19, TSC vulnerability and resilience coexist. There are both vulnerability and resilience elements in the supply side, demand side, government side, etc. The embedding of the objective attributes of tourism and health emergencies has brought the vulnerability of the TSC under the uncertain environment. At the same time, behind the disruption caused by the pandemic, the TSC does not lack resilience, and there is a power of recovery and breeding the opportunity of innovation and change.

- (2)

- All entities and individuals on the TSC have been affected and disrupted by various factors brought by COVID-19, which also prompted them to enhance their sense of community and cooperation. They work together, keep seeking ways to survive as well as prepare for tourism restart.

- (3)

- Government plays an important role in TSC recovery. The rise and fall of tourism are closely related to the government’s strict or relaxed travel policies, which affects the destination atmosphere, tourists’ risk perception and travel confidence. The supporting policies are related to the survival of tourism enterprises and further affect employment and social stability. Propagation and marketing can effectively send positive signals to the market and avoid information asymmetry. All of these are critical to tourism sustainable rebuilding.

- (4)

- The form of the TSC is being constantly innovated. Since offline tourism was blocked under the pandemic, online platforms such as microblogs, WeChat and short videos were developed as the “second scene” of tourism. Business models such as live broadcast, cloud travel and online commerce are constantly emerging, maintaining the positive interaction between the tourism supply side and the demand side, expanding new functions such as “tourism + social networking”, “tourism + entertainment” and “tourism + shopping” and forming a new type of virtual and multifunctional agglomeration TSC. At the same time, new technologies are empowering the TSC. AI, big data, automation, 5G and other technologies are introduced by various actors of the TSC, which inject new vitality into the TSC material and energy cycle.

- (5)

- Local TSC becomes more active. Under the pandemic prevention policy of “Do not go out of the city unless necessary”, people will turn to the local market to release tourism demand to a certain extent, which will stimulate the local TSC, such as purchasing more food and raw material resources locally, establishing more supplier enterprises and employing more local labor workers, thereby accelerating the progress of the local industry. Meanwhile, due to the fear of intensive risks and policy restrictions, the popularity of some crowded scenic spots will be reduced, bringing more opportunities to the scattered and marginalized tourist destinations, such as rural tourism.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

means full to capacity;

means full to capacity;  means crowded;

means crowded;  means normal;

means normal;  means comfort).

means comfort).

means full to capacity;

means full to capacity;  means crowded;

means crowded;  means normal;

means normal;  means comfort).

means comfort).

Appendix B

References

- Kumar, S.; Managi, S. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2020, 4, 481–502.1. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Shishodia, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Belhadi, A. Agriculture supply chain risks and COVID-19: Mitigation strategies and implications for the practitioners. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Time for reset? Covid-19 and tourism resilience. Tour. Rev. Int. 2020, 24, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukamuhabwa, B.R.; Stevenson, M.; Busby, J.; Zorzini, M. Supply chain resilience: Definition, review and theoretical foundations for further study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5592–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y.; Rice, B.J. A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Seville, E.; Opstal, V.D.; Vargo, J. A Primer in resiliency: Seven principles for managing the unexpected. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2015, 34, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 3, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Balaz, V. Tourism risk and uncertainty: Theoretical reflections. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Distribution Channels; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Scavarda, A.J.; Lustosa, L.J.; Scavarda, L.F. The tourism industry chain. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Conference of the Operations Management Society (POM 2001), Orlando, FL, USA, 30 March–2 April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S.J. Tourism Management: Managing for Change; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper, R.; Font, X. Tourism Supply Chains: Report of a Desk Research Project for the Travel Foundation; Leeds Metropolitan University, Environment Business & Development Group: Leeds, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Bititci, U.S. Performance measurement in tourism: A value chain model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism supply chain management: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ke, L. An Initial Discussion on the New Pattern of the Supply Chain in Tourism Industry. Tour. Trib. 2006, 3, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Shi, Y.; Liang, L.; Wu, H. Comparative analysis of underdeveloped tourism destinations’ choice of cooperation modes: A tourism supply—chain model. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1377–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Hu, J.; Yao, F. Big data empowering low-carbon smart tourism study on low-carbon tourism O2O supply chain considering consumer behaviors and corporate altruistic preferences. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 153, 107061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Social network analysis in smart tourism driven service distribution channels: Evidence from tourism supply chain of Uttarakhand, India. Int. J. Digit. Cult. Electron. Tour. 2018, 2, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. A supply chain management approach for investigating the role of tour operators on sustainable tourism: The case of TUI. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Practice: Building Capacity to Absorb Disturbance and Maintain Function; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, B.J.; Caniato, F. Building a secure and resilient supply network. Supply Chain Manag. Rev. 2003, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, H. Reconciling supply chain vulnerability, risk and supply chain management. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2006, 9, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.P.; Christopher, M.; Allen, P. Agent-based modelling of complex production/distribution systems to improve resilience. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2007, 10, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, Y.S.; Holcomb, C.M. Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, T.S.; Koronis, E. Supply chain resilience: Definition of concept and its formative elements. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.M. Fostering emergent resilience: The complex adaptive supply network of disaster relief. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 1970–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, N.-O.; Feisel, E.; Hartmann, E. Research on the phenomenon of supply chain resilience: A systematic review and paths for further investigation. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Khan, A.Q.; Rashid, K.; Rehman, S.U. Achieving supply chain resilience: The role of supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain agility. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Venkatesh, M. Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Measuring risks and vulnerability of tourism to the COVID-19 crisis in the context of extreme uncertainty: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucco, M.; De Giovanni, P. Achieving Resilience and Business Sustainability during COVID-19: The Role of Lean Supply Chain Practices and Digitalization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S. The rigor of case study research in supply chain management. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Conference for Nordic Researchers in Logistics of NOFOMA, Oslo, Norway, 8–9 June 2005; Jahre, M., Persson, G., Eds.; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria Díaz, J.M.; Aguiar Quintana, T.; Araujo Cabrera, Y. Tourist Renewal as a Strategy to Improve the Competitiveness of an Urban Tourist Space: A Case Study in Maspalomas-Costa Canaria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Mimi, L.; Shaowua, L. A Narrative Analysis of Destination Decision Making Process of Millennium Outbound Tourists: The Role of Opportunity-driven Decision Making. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, E.W. The Enlightened Eye: Qualitative Inquiry and the Enhancement of Educational Practice; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner, P.P.; Kivlighan, D.M.; Wampold, B.E. Research Design in Counselling; Brooks Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.E.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N. A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns. Psychol. 1997, 25, 517–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N.; Hess, S.A.; Ladany, N. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, B.L., II; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; Mc Carthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Chirstensen, L.; Schiller, A. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sönmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Lemke, M.K.; Hsieh, Y.C.J. Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on the health and safety of immigrant hospitality workers in the United States. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueroso, F.; Jansen, M. Una Valoraci’ on de los ERTE Para Hacer Frente a la Crisis del COVID-19 en Base a la Evidencia Empíricay Desde una Perspectiva Comparada (No. 2020-06); FEDEA: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.; Scott, D.; Gossling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Xiang, Z. e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Interviewee | Brief Narrative |

|---|---|---|

| January 2021 | G-03 Administrative staff of the Tourism Bureau | In order to ensure the safety of tourists, all scenic spots in Lijiang have implemented strict pandemic prevention and control measures of “limit, peak staggering, appointment” according to the requirements of the authority. For example, the Lugu Lake scenic spot has implemented Sichuan-Yunnan jointly measures to limit the flow of tourists, Yulong Snow Mountain scenic area set a maximum daily capacity at 43,500, once reached, stop selling tickets, the tourist reception of Lijiang Old Town cannot exceed 75% of its maximum capacity, and the flow should be strictly controlled. |

| March 2021 | TA-02 Travel agency executive | From January to July 2019, we received about 200,000 tourists, but only 80,000 in the same period this year. During the past six months, the pandemic spread from Ruili to Nanjing and then to Zhangjiajie, the butterfly effect brought by the repeated outbreak has made Lijiang tourism like the stock market, alternately turning red and green. 2020 was supposed to be tough, but unexpectedly, this year (2021) was even tougher. |

| April 2021 | Ac-05 Innkeeper | In two years, I lost 1 million (yuan). This year, I have to pay 4 years’ rent to the landlord in a lump sum. I tried to negotiate with the landlord to pay it in two years, but was rejected. Alas, it won’t work if I don’t pay, more than two million was invested in the decoration, it is really a dilemma. The boss next door has stayed here for nearly 20 years, but this year, he can’t stand it anymore. His rent was just due and he went back to his hometown. I don’t even have a chance to go back doing manual work. |

| April 2021 | G-01 Government worker | Under the pandemic, “stabilizing employment” in the tourism industry has become an important work for us. Objectively speaking, each market player is facing difficulties. Enterprises have no revenue, but need to pay rents and wages, it is not easy to survive. Practitioners’ salary reduce, life is not easy. We are making efforts to strengthen policy adjustment, and call on all sectors of society to joint force together to get through the crisis. |

| July 2021 | Fo-16 Restaurant owner | In order to prepare for the peak tourism season in Lijiang, I have stored more than 200,000 yuan food materials and trained nearly 100 service personnel in my several hot pot restaurants, hoping to make up for last year’s losses. Who could have expected the rebound of the pandemic and all the money have gone down the drain! |

| July 2021 | T-10, Tourist | After my son finished his college entrance examination, I brought him to Lijiang. We both like music, so we spent most of the day in the folk bar in the Old Town. Maybe it was because of the rainy season, there was very few people, just us two and some staff, so I chatted with the resident singers. It was not until evening that a table or two of guests came, so lonely, completely lost the hustle and bustle of the past, much to my son’s disappointment. Well, it is all caused by the pandemic. |

| August 2021 | TA-11, Middle managers of travel agencies | Recently, our travel agency only receives more than 20 individual tourists a day, and was not allowed team reception. It is said that there’s a travel agency has been severely punished for violation of the rule, so each agency dare not act recklessly. The front-line staff have been dismissed home, with a basic salary of more than 1000 yuan a month. The rest of us are also idle panic. I have started to take bus or walk to work, at least can keep fit. |

| August 2021 | Tr-10 Tour bus driver | At the beginning of the pandemic, I was quite happy, thinking that I finally have a chance to rest. But later things went wrong, the pandemic continued and my transport line was shut down. I tried to do some other jobs, but they were not very good, and I cannot do them well, truly no occupation was easy. There are kinds of expenses in my family that can’t be saved. If it continues any more, I have to consider selling my car. What I miss most now is tourists. |

| 4 September 2021 | Notes of the project team | Since Yunnan Province suspended cross-provincial tourism activities on 5 August 2021, it is now September, and the Lijiang old town is still silent and quiet. From the big waterwheel to Yuhe Square, East Street, Sifang Square, Wuyi Street...Even the most lively and prosperous area in the past was also sparsely pedestrian, with a few people passing by occasionally, mostly locals. All kinds of businesses in the Old Town-shops, inns, restaurants, cultural and creative industries, most have been closed. Even the riverside restaurant that was supposed to be full at this time in previous years, is now empty, leaving only the waiters who brush their mobile phones or boring in a daze. |

| Time | Events | Background |

|---|---|---|

| 25 January 2020 | All businesses of the company were suspended successively | COVID-19 outbreak nationwide, government and authorities’ demands |

| 20 February 2020 | Combining the type and nature of the business, the tourist reception work resumed in an orderly manner in batches | The pandemic had been effectively controlled, and the overall situation had improved |

| 1 March 2020 | Indigo Hotel in Moonlight City of Shangri-la opened for business | The pre-pandemic plan continued |

| 22 May 2020 | The business of the company was fully resumed | The pandemic situation tended to be stable, but due to the impact of some domestic areas and foreign pandemic situations, the number of tourists received had not fully recovered |

| August 2020 | Seeking Cloud Vacation Hotel in Mosuo Town opened to the public, which is a Lugu Lake related project | Continued to promote Lugu Lake related projects as the “second main battlefield” |

| 2nd half of 2020 | The net profit returned to positive and gradually improved | Inter-provincial tourism recovery; driven by summer vacation, Mid-Autumn Day, National Day |

| 2021 Spring Festival | Intra-provincial and inter-provincial tours were restricted | The pandemic was still spreading worldwide. Many sporadic cases and even localized clustering pandemics had occurred in China, and the pandemic prevention and control situation was still severe and complicated. The country advocated local Spring Festival celebrations |

| 1st half of 2021 | All businesses were opened and operated normally, but the tourist reception volume failed to fully recover | The overall situation of the pandemic was under control but was still affected by the situation in some areas in China and abroad |

| 5 August 2021 | The company suspended inter-provincial tourism activities | There were medium and high-risk areas in Yunnan Province, which required pandemic prevention and control |

| 15 September 2021 | Resuming inter-provincial tourism business | The medium and high-risk areas in Yunnan were cleared; the Culture and Tourism Department of Yunnan Province issued a notice on the restoration of inter-provincial tourism |

| 2021. National Day Golden Week | The flow of people had surged, and the holiday economy was booming | Driven by the National Day Golden Week, people’s long-suppressed tourism demand had been released |

| 16 October 2021 | The number of group tourists from outside the province decreased sharply, and the total number of tourists decreased significantly | The emergence of a “travel group transmission chain”, a new round of COVID-19 had spread to 20 provinces in China |

| Main Business (RMB 100 Million) | 2021H1 | 2020H1 | 2019H1 | 2018H1 | 2019 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 2.02 | 0.95 | 3.18 | 3.43 | 7.23 | 6.78 |

| Cableway revenue | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.59 | 2.05 | 3.31 | 3.90 1 |

| Proportion of cableway revenue | 48.28% | 54.21% | 49.89% | 59.77% | 45.78% | 57.52% |

| Impression Lijiang performance | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 1.77 | 0.97 |

| Proportion of performance | 15.71% | 12.90% | 23.85% | 14.83% | 24.48% | 14.31% |

| Hotel business | 0.52 | 0.21 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.19 | 1.1 |

| Proportion of hotel business | 25.79% | 22.23% | 15.74% | 14.63% | 16.46% | 16.22% |

| Catering services | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.12 |

| Proportion of catering services | 2.94% | 2.50% | 2.09% | 2.51% | 3.73% | 1.77% |

| Time | Interviewee | Brief Narrative |

|---|---|---|

| January 2021 | TC-01, Senior executive of Lijiang Co., Ltd. | First of all, I would like to thank the policy support. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, relevant government departments have successively issued policies to reduce or exempt the value-added tax and its surtax, real estate tax and land use tax of the tourism industry for the whole year, as well as pension insurance, unemployment insurance, work-related injury insurance and medical insurance. Our Lijiang Co., Ltd. and subsidiaries have received a total reduction of more than 40 million yuan, which is really a timely help to the recovery of the company’s performance. |

| February 2021 | TA-02, Travel agency manager | Now the novel coronavirus is serious, Yunnan has stopped inter-provincial tourism. Almost all travel agencies in Lijiang have stopped operating, except us. Without tourists, we train, study, plan routes to practice our internal skills. Maybe the tourism will restart tomorrow, we must fully prepare for it. |

| February 2021 | F-21, Villagers around Lijiang | As the outbreak continued, our family has resumed agricultural planting and bought dozens of sheep. We are farmers, it is not a problem to rely on farming to make a living. There is no problem planting some land to feed our family, and with dozens of sheep, we can still get on with life. We need to prepare for the long-term “fight” against COVID-19. |

| March 2021 | TA-08, Tour guide with property in the Old Town | In the past, I used to be a guide in the peak season, fishing or entertainment with friends, life is easy and stress-free. However, there was suddenly no group to take these two years, I gradually began to panic. My wife and I were discussing to invest an express service node. You can’t just sit there and wait. The most important thing is not to be idle every day, or the spirit will be decadent. |

| April 2021 | Fo-14, Catering self-employed | If I keep My restaurant open, there has few customers a day, almost no profit after paying utilities; If we don’t open, the rent will still be paid. Fortunately, my husband’s business of repairing electric vehicles is not bad, the cost of school for our two children and the monthly payment of the house all depends on him, so the life can still be maintained. |

| May 2021 | TC-04, Travel photography company | Travel photography has never gotten better in 2021, and it is difficult to change careers, neither I have technology or capital. I was looking forward to the peak season of another year like everyone, but waiting for two years, the pandemic has gone back and forth, some stores have been closed and opened and closed. Last year, when there were no tourists, we tried to position the market into citizen-oriented services, taking some personal, parent-child and family photos. Now the pandemic is gradually improving, we start taking pictures of ethnic minorities in the Old Town, which are very popular at affordable prices. In my spare time, I also do some wechat business, selling local specialties such as Lijiang black apples, soft-seed pomegranates and so on. Life is half poetic, half fireworks, we should live it worthy. |

| June 2021 | M-03, New media artist | Although I am not a direct tourism practitioner, and my income has not been affected for the time being, but my main customers are from tourism industry. I shoot videos, post official accounts, and write copywriters to help them attract tourists and increase visitor flow. Tourism has been depressed for a long time, if the lips are gone, the teeth will be cold, so I have been constantly adjusting my thinking. A while ago, I began to try to sell goods through live broadcast, delivering local catering specialties of Lijiang to outside. However, the competition is so fierce that it is difficult to enter a new industry. In constant reflection, I believe that tourism still needs to deeply cultivate culture and brand in order to remain invincible. |

| July 2021 | Tr-23, Self-employed passenger transport | My family has a van and a business car to pick up and drop off tourists. In the previous peak season, my husband and I were so busy from morning to night that couldn’t see each other, but it’s too idle now. Fortunately, this is the season of wild mushrooms in Lijiang, he goes up the mountains to find fungus to sell, I continue to run the car. Since there are fewer tourists, it’s too expensive to keep two cars, we’re ready to sell one. |

| September 2021 | TS-19, Scenic spot cleaner | After the pandemic, I find one thing interesting. Many tourists come to our scenic spot bringing their own garbage bags. They not only stop littering, but also take garbage away. Once I saw a tourist taking his child to pick up rubbish thrown by others, I was so moved. The pandemic has made more and more tourists pay attention to protecting the environment. |

| 17 September 2021 | Notes of the project team | As soon as I entered the Old Town, I felt that the flow of people near the big waterwheel and Yuhe Square has increased a lot. There are tourists taking pictures around the waterwheel, walking in groups of three or five, calling or answering the phone, sightseeing or resting, as if stepping back to the past, business as usual, time is good. Especially in the bar street, crowded with tourists and the atmosphere is excitement, giving people a long-lost sense of familiarity. The real-time big data shows that, at 8 p.m., the number of tourists is 14,853, plus the resident population and working staff, the total number exceeded 24,000. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, H.; Ran, W. Analysis of the Vulnerability and Resilience of the Tourism Supply Chain under the Uncertain Environment of COVID-19: Case Study Based on Lijiang. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052571

Bai H, Ran W. Analysis of the Vulnerability and Resilience of the Tourism Supply Chain under the Uncertain Environment of COVID-19: Case Study Based on Lijiang. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052571

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Haixia, and Wenxue Ran. 2022. "Analysis of the Vulnerability and Resilience of the Tourism Supply Chain under the Uncertain Environment of COVID-19: Case Study Based on Lijiang" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052571

APA StyleBai, H., & Ran, W. (2022). Analysis of the Vulnerability and Resilience of the Tourism Supply Chain under the Uncertain Environment of COVID-19: Case Study Based on Lijiang. Sustainability, 14(5), 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052571