Logos, Ethos, Pathos, Sustainabilitos? About the Role of Media Companies in Reaching Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sustainability and Sustainable Development

3. Media (and) Sustainability

4. Previous Research

5. Materials and Methods

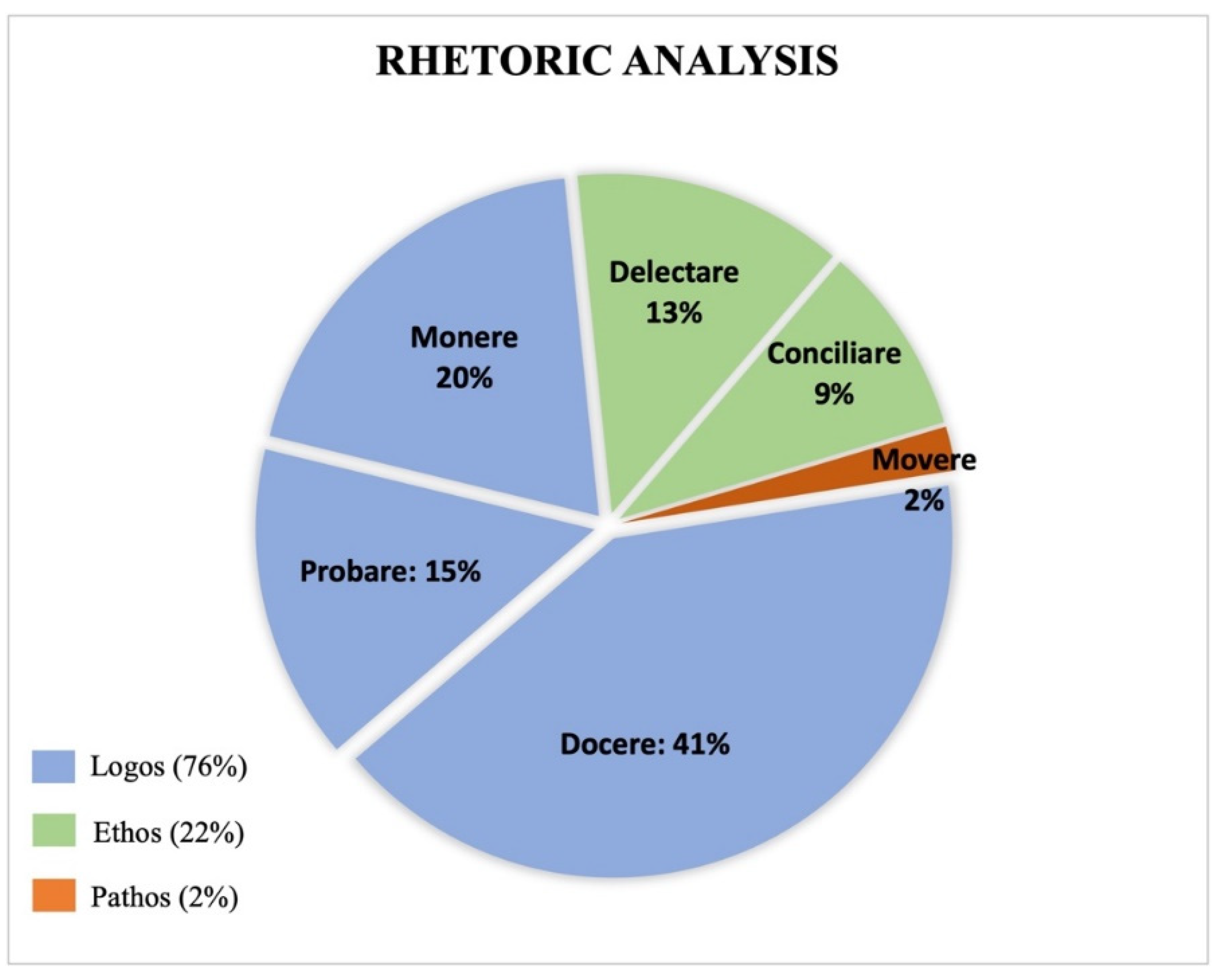

- The informative docere (to instruct). This technique is characterized by emotion-free information about an issue and wants to signalize objectivity.

- The argumentative probare (to prove). This technique is used to support the credibility of the narration through factual evidence, such as scientific data. It is used to serve the underlying argumentation, which should be referential and logical.

- The logical–ethical monere (to warn). This technique intends to educate the recipients on a moral level by appealing to their rationality [21].

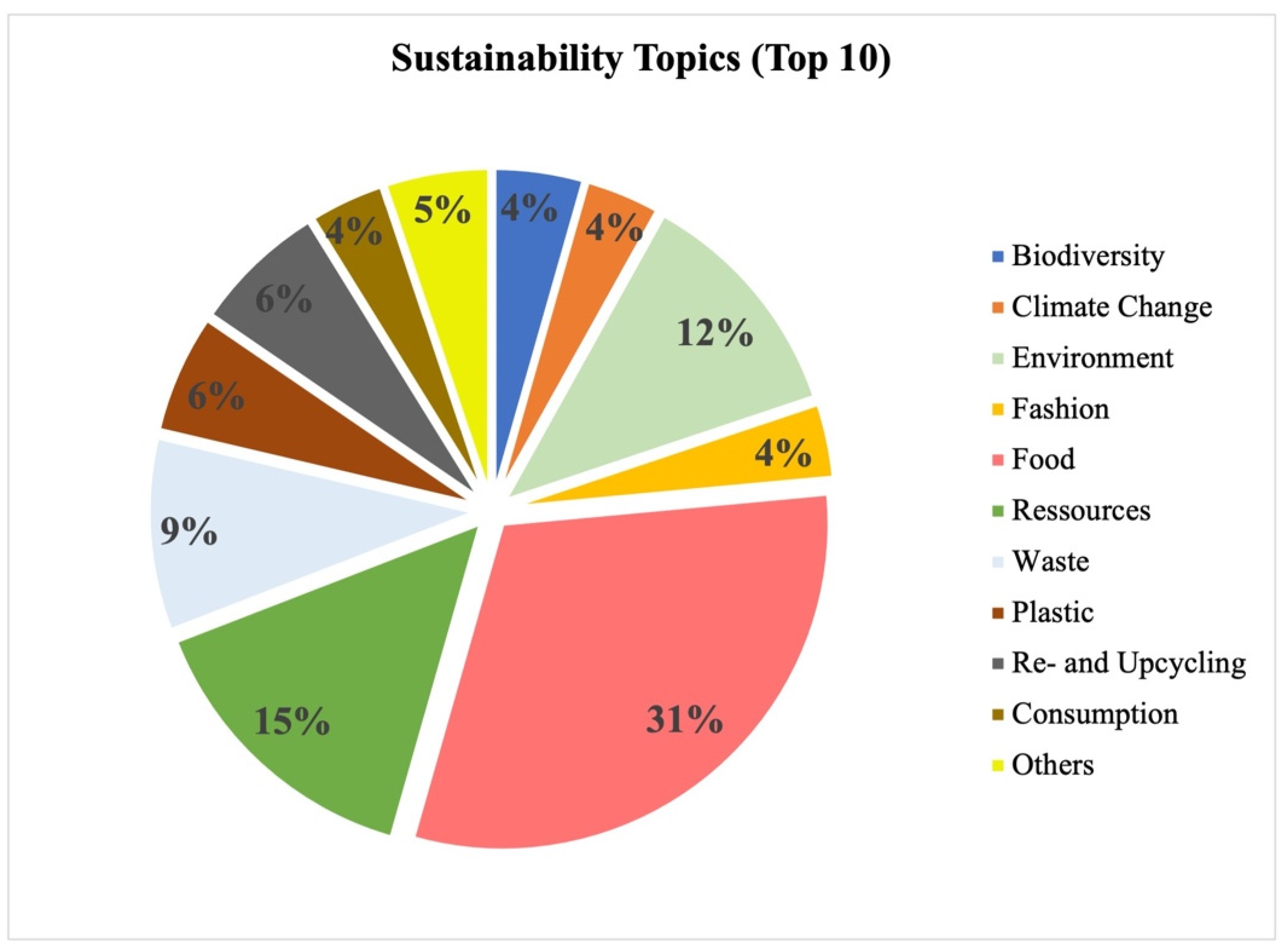

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Text Passage * | Paraphrase | Main Category |

|---|---|---|

| “Biodiversity forms the basis of our life. It is essential to preserve biodiversity and species diversity. The two terms are often used as synonyms. However, the term biodiversity includes much more than species diversity: it is about the interrelationship of organism and the environment.” | Biodiversity is more than diversity of species | Biodiversity |

| “The greenest building in Europe. We present you sustainable architecture with climate protection.” | Green architecture with climate protection | Buildings |

| “What are the causes and risks of climate change? How does the greenhouse effect work? What are simple tricks everyone can apply to help protect the climate? Here you can find out more!” | Causes and risks of climate change and what can be done about it | Climate Change |

| “Germans buy on average 60 clothing articles every year—even if they never wear around 40 percent of them. What do the wardrobeof our celebrities look like?” | Consumption practices of German celebrities | Consumption |

| “Sustainable tips from Grandma Tita: Saving water and money in the household it’s easy with these tricks.” | How to save money and water | Cost saving |

| “The small Danish Island of Ærø with its 4000 inhabitants is a role model for environmental protection and energy transition. One particularly advanced feature is that environmental protection is a regular subject on the school timetable.” | Environmental protection as regular subject at school | Education |

| “Things are very bad for the green lung—our forest! In Germany alone, over 120,000 hectares of forest have died since 2018. Fires, storms, drought, and parasites continue to threaten the forest.” | Life-threatening conditions for the forest | Environment |

| “The old saying ‘you are what you eat’ can be well applied to our own carbon footprint. Our diet is an important factor in determining how many climate-damaging greenhouse gases we produce in our daily lives and how large our ecological footprint is.” | Food choices have an impact on our carbon footprint | Food |

| “On Friday, there will be an unusual experiment: Singer Wincent Weiss will compete on a trip from Hamburg to Mannheim against a fan driving from Dresden to Cologne. Both will complete the 570-km route from north to south and from east to west in e-cars, showing how ‘fit’ Germany is when it comes to e-mobility.” | Challenge to examine Germany’s e-mobility development | Mobility |

| “On supermarket shelves, huge numbers of products are packaged in plastic. But there almost always alternatives—sometimes they are only a little bit hidden.” | Plastic packages in supermarkets and its alternatives | Plastic |

| “Pirmin Berille has committed himself to reducing his ecological footprint. Since 2019, he has been living with his two children in a yurt made largely of upcycled material.” | Alternative lifestyle through re- and upcycling | Re- and Upcycling |

| “We consume an average of 130 L of water per day per person in our households. Quite a lot if you imagine this amount filled into bottles. Only about 3 to 4% of it is drunk or used for cooking. Instead, most of the water flows through our tap when we shower or is used for flushing the toilet. However, if you change a few of your habits, you can easily reduce your water consumption.” | How to reduce water waste and consumption | Resources |

| “This is how harvesters are ripped off in Germany. ‘Modern slavery’ for our cheap fruit and vegetables. Harvesters were bitterly disappointed in search of a better life.” | Exploitation of cheap workers | Social Sustainability |

| “Everyone is talking about sustainability—but what does it actually mean? In a classic sense, sustainability means that we should not consume more resources than can be regenerated or provided.” | Explanation of the term sustainability | Sustainability |

| “The list of problems caused by mass tourism is endless—let’s tackle them! 5 pro-tips for sustainable travel that everyone can implement!” | Mass tourism problems and possible solutions | Travel |

| “Around 12 million tons of food are thrown away in Germany every year—more than half of it in private households. Yet around 40 percent of this food would be still edible.” | Food is thrown away even thought is still edible | Waste |

References

- Weder, F.; Karmasin, M.; Krainer, L.; Voci, D. Sustainability communication as critical perspective in media and communication studies—An introduction. In The Sustainabiliy Communication Reader. A Reflective Compendium; Weder, F., Krainer, L., Karmasin, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D.; Lüdecke, G.; Godemann, J.; Michelsen, G.; Newig, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Schulz, D. Sustainability communication. In Sustainability Science: An Introduction; Heinrichs, H., Martens, P., Michelsen, G., Wiek, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, M.S.; Bonfadelli, H. Umwelt- und Klimakommunikation. In Forschungsfeld Wissenschaftskommunikation; Bonfadelli, H., Fähnrich, B., Lüthje, C., Rhomberg, M., Schäfer, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. Researching risk and the media. Health Risk Soc. 1999, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R. Media, crisis and SARS: An introduction. Asian J. Commun. 2005, 15, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, R.E.; McMakin, A.H. Risk Communication: A Handbook for Communicating Environmental, Safety, and Health Risks, 6th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Glik, D. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2007, 28, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, B.J.; Heinrich, N.; Hancock, S.; Lestou, V. Communicating with the public during health crisis: Experts’ experiences and opinions. J. Risk Res. 2009, 12, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, C. The effect of social media use on preventive behaviors during infectious disease outbreaks: The mediating role of self-relevant emotions and public risk perception. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirz, C.D.; Mayorga, M.; Johnson, B.B. A longitudinal analysis of Americans’ media sources, risk perceptions, and judged need for action during the Zika outbreak. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.S.; Schlichting, I. Media Representations of Climate Change: A Meta-Analysis of the Research Field. Environ. Commun. 2014, 8, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How People Access News about Climate Change. In Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Available online: https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/how-people-access-news-about-climate-change/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Newig, J.; Schulz, D.; Fischer, D.; Hetze, K.; Laws, N.; Lüdecke, G.; Rieckmann, M. Communication regarding sustainability: Conceptual perspectives and exploration of societal subsystems. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2976–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karmasin, M.; Voci, D.; Weder, F.; Krainer, L. Future perspectives: Sustainability communication as scientific and societal challenge. In The Sustainability Communication Reader: A Reflective Compendium; Weder, F., Krainer, L., Karmasin, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele, D.A. Science communication as political communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111 (Suppl. S4), 13585–13592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, A. Reflections on environmental communication and the challenges of a new research agenda. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum 2007, 38, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušková, S.; Hák, T.; Nečas, V.; Moldan, B. Sustainable development—A poorly communicated concept by mass media. Another challenge for SDGs? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weder, F.; Einwiller, S.; Eberwein, T. Heading for new shores: Impact orientation of CSR communication and the need for communicative responsibility. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weder, F.; Karmasin, M. Corporate Communicative Responsibility. Kommunikation als Ziel und Mittel unternehmerischer Verantwortungswahrnehmung–Studienergebnisse aus Österreich. zfwu Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts-und Unternehmensethik 2011, 12, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, H.F. Einführung in die Rhetorische Textanalyse, 9th ed.; Buske: Hamburg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, A.; Kopfmüller, J. Nachhaltigkeit; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; Main, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Adomßent, M.; Godemann, J. Sustainability Communiction: An Integrative Approach. In Sustainability Communication; Godemann, J., Michelsen, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, A. Nachhaltigkeit Verstehen. Arbeiten an der Bedeutung Nachhaltiger Entwicklung; Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M.; Shaw, D. The agenda setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.R. Sociology of Mass Communications. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1979, 5, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Siegert, G.; von Rimscha, B. Economic bases of communication. In Theories and Models of Communication; Cobey, P., Schulz, P.J., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, C. Gezielte Krisenkommunikation im Spannungsfeld von medienökonomischen Zwängen und politischen Imperativen. In Sicherheit und Medien; Jäger, T., Viehring, H., Eds.; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jarren, O.; Meier, W.A. Mediensysteme und Medienorganisationen als Rahmenbedingungen für den Journalismus. In Journalismus—Medien—Öffentlichkeit: Eine Einführung; Jarren, O., Weßler, H., Eds.; Opladen: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 99–163. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus, E. Öffentlichkeitstheorien im europäischen Kontext. In Europäische Öffentlichkeit und Medialer Wandel. Eine transdisziplinäre Perspektive; Lagenbucher, W.R., Latzer, M., Eds.; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Burkart, R. Kommunikationswissenschaft. In Grundlagen und Problemfelder/Umrisse einer Interdisziplinären Sozialwissenschaft, 4th ed.; Böhlau Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- von Rimscha, B.; Siegert, G. Medienökonomie. Eine Problemorientierte Einführung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jarren, O.; Donges, P. Politische Kommunikation in der Mediengesellschaft; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.J. Die Welten der Medien: Grundlagen und Perspektiven der Medienbeobachtung; Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Olkkonen, L. Audience enabling as corporate responsibility for media organizations. J. Media Ethics 2015, 30, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandoval, M. Corporate social (ir)responsibility in media and communication industries. In Media and Left; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 166–189. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, S.J. Introduction to Mass Communication: Media Literacy and Culture, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.; Deegan, C. The public disclosure of environmental performance information—A dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1998, 29, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch-Elkon, Y. Studying the media, public opinion, and foreign policy in international crises: The United States and the Bosnian Crisis, 1992–1995. Int. J. Press Polit. 2007, 12, 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG Media Compact. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sdg-media-compact-about/ (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Luhmann, N. Ecological Communication; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, K.; Morrison, M. Communicating climate change: A literature review. Presented at the 55th Annual AARES National Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 8–11 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brodscholl, P.C. Negotiating Sustainability in the Media: Critical Perspectives on the Popularisation of Environmental Concerns. Ph.D. Dissertation, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suhonen, P. Environmental issues, the Finnish major press, and public opinion. Gazette 1993, 51, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Ivanova, A.; Schäfer, M.S. Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dispensa, J.M.; Brulle, R.J. Media’s social construction of environmental issues: Focus on global warming—A comparative study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. 2003, 23, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boykoff, M.T.; Roberts, J.T. Media coverage of climate change: Current trends, strengths, weaknesses. Hum. Dev. Rep. 2007, 2008, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Castrechini, A.; Pol, E.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J. Media representations of environmental issues: From scientific to political discourse. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 64, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, N.T. Global warming and the British press: The emergence of an issue and its political implications. In Elections Public Opinion and Parties Conference; Bristol University: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, N.T. Addressing climate change: A media perspective. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.B.; Durfee, J.L. Testing public (un) certainty of science: Media representations of global warming. Sci. Commun. 2004, 26, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M. Talking about a Revolution: Climate Change and the Media; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2004, 14, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M.T. Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006. Area 2007, 39, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olausson, U. Global warming—Global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty. Public Underst. Sci. 2009, 18, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Petri, H.; Arlt, D. Constructing an illusion of scientific uncertainty? Framing climate change in German and British print media. Communications 2016, 41, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. Reporting the climate change crisis. In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism Studies; Allan, S., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Badullovich, N.; Grant, W.; Colvin, R. Framing climate change for effective communication: A systematic map. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Liu, Y.; Tran, D.V. Nationalizing a global phenomenon: A study of how the press in 45 countries and territories portrays climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumbo, C. Constructing climate change: Claims and frames in US news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Underst. Sci. 1996, 5, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verro, D. Media Framing of Anthropogenic Climate Change in the Russian Federation; Helsingin Yliopisto: Helsinki, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weder, F.; Voci, D.; Vogl, N.C. (Lack of) problematization of water supply use and abuse of environmental discourses and natural resource related claims in German, Austrian, Slovenian and Italian media. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 12, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shehata, A.; Hopmann, D.N. Framing climate change: A study of US and Swedish press coverage of global warming. J. Stud. 2012, 13, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, T.; Shapiro, M.A. The US news media, polarization on climate change, and pathways to effective communication. Environ. Commun. 2018, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Macmillan, A.; Rudd, C. Framing climate change and health: New Zealand’s online news media. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecula, D.A.; Merkley, E. Framing climate change: Economics, ideology, and uncertainty in American news media content from 1988 to 2014. Front. Commun. 2019, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voci, D.; Bruns, C.J.; Lemke, S.; Weder, F. Framing the End: Analyzing Media and Meaning Making During Cape Town’s Day Zero. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höijer, B. Emotional anchoring and objectification in the media reporting on climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 2010, 19, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.W.; Joffe, H. Climate change in the British press: The role of the visual. J. Risk Res. 2009, 12, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausstattung mit Gebrauchsgütern. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Einkommen-Konsum-Lebensbedingungen/Ausstattung-Gebrauchsgueter/Tabellen/liste-unterhaltungselektronik-d.html (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Bevölkerung: Deutschland. Available online: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=12111-0001&bypass=true&levelindex=0&levelid=1640689809688#abreadcrumb (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- 8 Dinge, die Sie noch Nicht über die Deutsche Sprache Wussten. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/fakten-deutsche-sprache-1723168 (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Ksiazek, T.B.; Webster, J.G. Cultural Proximity and Audience Behavior: The Role of Language in Patterns of Polarization and Multicultural Fluency. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2008, 52, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahresrückblick der Mediengruppe RTL Deutschland. Available online: https://kommunikation.mediengruppe-rtl.de/meldung/Jahresrueckblick-der-Mediengruppe-RTL-Deutschland/ (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Jahresabschluss zum 31. Dezember 2020 und Langbericht. Available online: https://www.prosiebensat1.com/uploads/2021/04/22/P7S1%20Media%20SE%20JA%202020_DE%281%29.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- TV-Markt 2020/2021. Available online: https://www.quotenmeter.de/n/127337/tv-markt-2020-2021-irrelevanz-des-privat-tvs-nimmt-zu (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Packen wir’s an. Available online: https://www.rtl.de/cms/packen-wir-s-an-fuer-verantwortungsvolles-essen-4607554.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- “Packen wir‘s an!”: RTL-Themenwoche über Ernährung. Available online: https://www.wunschliste.de/tvnews/m/packen-wir-s-an-rtl-themenwoche-ueber-ernaehrung-und-lebensmittelverschwendung (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Die SAT.1 Waldrekord-Woche. Available online: https://www.sat1.at/tv/die-sat-1-waldrekord-woche (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Grüner Geht‘s Nicht: Die Erste “SAT.1 Waldrekord-Woche”. Available online: https://tvheute.at/news/gruener-gehts-nicht-die-erste-sat1-waldrekord-woche--zeichen-gegen-die-klimakrise-start-am-15-maerz-2021-_1860732111 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. 2016. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sanders, W. Vorläufer der Textlinguistik: Die Stilistik. In Text- und Gesprächlinguistik—Linguistic of Text and Conversation; Brinker, K., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- QRS International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Released in March 2020). Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Skitka, L.J.; Hanson, B.E.; Morgan, G.S.; Wisneski, D.C. The Psychology of Moral Conviction. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skitka, L.J.; Wisneski, D.C.; Brandt, M.J. Attitude moralization: Probably not intuitive or rooted in perceptions of harm. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wisneski, D.C.; Skitka, L.J. Moralization through moral shock: Exploring emotional antecedents to moral conviction. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brennan, L.; Binney, W. Fear, guilt, and shame appeals in social marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anastasiei, B.; Dospinescu, N. Facebook advertising: Relationship between types of message, brand attitude and perceived buying risk. Ann. Constantin Brancusi Univ. Targu-Jiu Econ. Ser. 2017, 6, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiei, B.; Dospinescu, N. Paid Product Reviews in Social Media—Are They Effective? In Proceedings of the 34th International Business Information Management Association Conference, Vision, Madrid, Spain, 13–14 November 2019; Volume 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalskyi, B.; Holubnyk, T.; Dubnevych, M.; Pysanchyn, N.; Selmenska, Z. Optimization of the Process of Determining the Effectiveness of Advertising Communication. In Data-Centric Business and Applications; Ageyev, D., Radivilova, T., Kryvinska, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, L.D.; Fleszar-Pavlovic, S.; Khachikian, T. Changing Behavior Using the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation. In The Handbook of Behavioral Change; Hagger, M.S., Cameron, L., Hamilton, K., Hankonen, N., Lintunen, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gall Myrik, J. The Role of Emotions in Preventive Heath Communication; Lexington Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pantti, M. Disaster news and public emotions. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions and Mass Media; Döveling, K., von Scheve, C., Konijn, E.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.M. Emotion in persuasion and risk communication. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions and Mass Media; Döveling, K., von Scheve, C., Konijn, E.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; DeWall, C.N.; Zhang, L. How Emotion Shapes Behavior: Feedback, Anticipation, and Reflection, Rather Than Direct Causation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Text Passage * | Rhetoric Technique | Method of Persuasion |

|---|---|---|

| “Dirty water must be treated to become safe drinking water. Filters and membrane processes remove even the smallest particles from the water. The slow sand filter process is considered an environmentally friendly and chemical-free process.” | Docere | Logos |

| “According to research published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, regular meat consumption increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, and cancer” | Probare | |

| “Buy only what you really need so that nothing has to be thrown away. In the supermarket, also look for food that has almost reached its best-before date. They are still in perfect condition and are not thrown away later.” | Monere | |

| “Because: each of us has to buy food—and each of us can influence how sustainably this is done with our purchasing behavior.” | Conciliare | Ethos |

| “Fair fashion has long said goodbye to its dusty eco-image and can no longer be distinguished from conventional mass-produced textiles in terms of style.” | Delectare | |

| “Shocking numbers: that is how much commercial kitchens throw away every day. It almost makes you lose your appetite. It would be very easy to stop this madness.” | Movere | Pathos |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voci, D. Logos, Ethos, Pathos, Sustainabilitos? About the Role of Media Companies in Reaching Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052591

Voci D. Logos, Ethos, Pathos, Sustainabilitos? About the Role of Media Companies in Reaching Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052591

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoci, Denise. 2022. "Logos, Ethos, Pathos, Sustainabilitos? About the Role of Media Companies in Reaching Sustainable Development" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052591

APA StyleVoci, D. (2022). Logos, Ethos, Pathos, Sustainabilitos? About the Role of Media Companies in Reaching Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 14(5), 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052591