1. Introduction

International trade frictions between countries intensify, tariff barriers rise, and retaliatory tariffs are frequently imposed. Free trade is shrinking, and protectionism is strengthening. These recent trends threaten the sustainability of the international trade order.

The rapid growth of trade between low- and high-income economies raises concerns about its impact on domestic labor markets in high-income countries [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The increase in China’s trade with other countries has dramatically changed world trade patterns over the past few decades, leading policymakers to rethink domestic labor market adjustments and their implications. China’s share of world exports has increased from less than 2% in 1998 to 14.7% in 2020, with China’s primary export being manufactured goods (UNCTAD,

https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan (accessed on 3 February 2022)). In the United States, for instance, numerous manufacturing jobs have been lost to increasing imports of manufactured goods from China [

15].

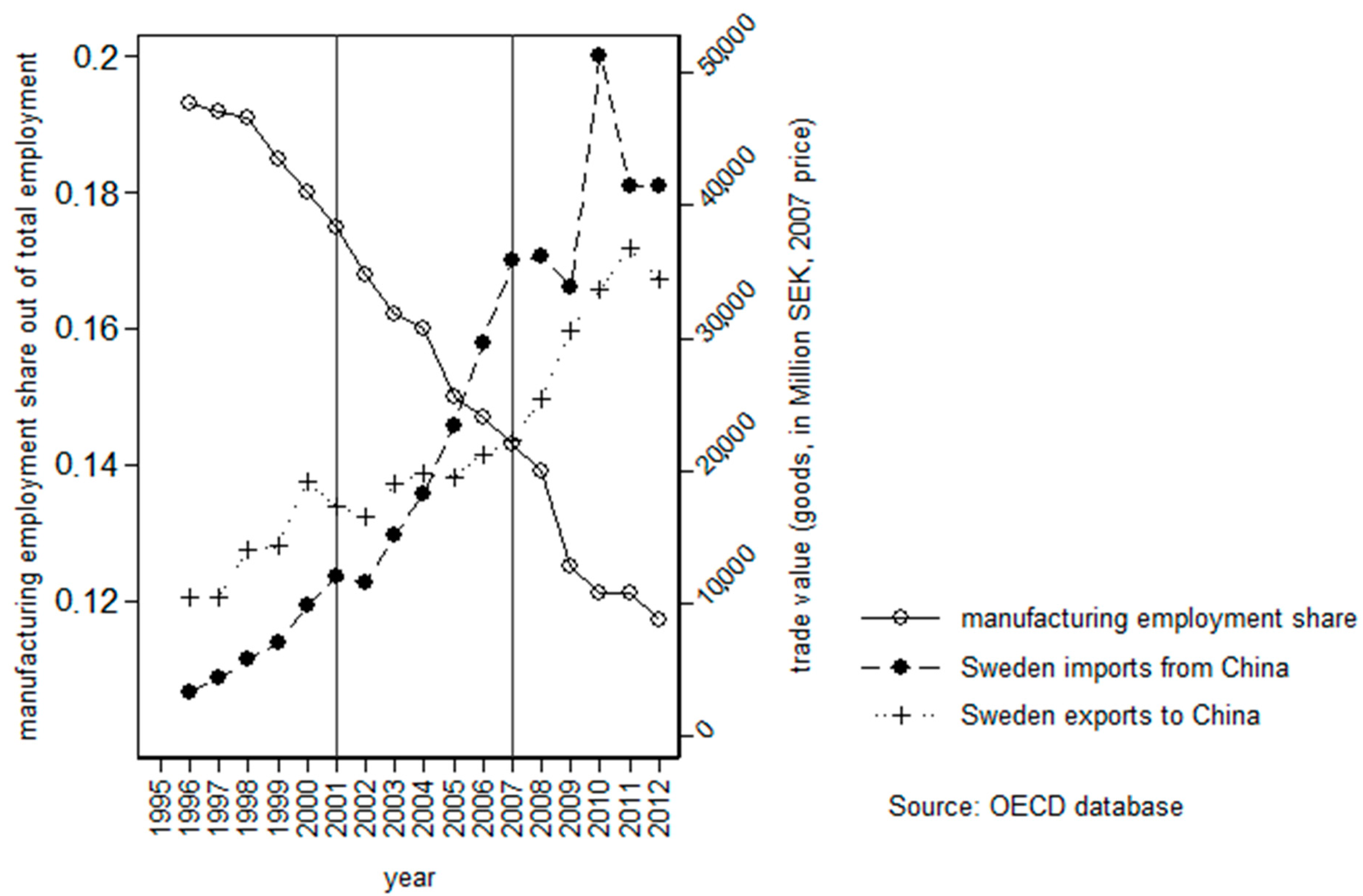

Like other high-income countries, the Sweden-China trade has also increased substantially. According to the National Board of Trade (

https://statistikblad.kommerskollegium.se (accessed on 3 February 2022)), in 2020, the total value of Sweden’s exports to China amounted to SEK 78 billion, and imports from China amounted to SEK 85.2 billion, which constitutes 5.5% and 6.2% of Sweden’s total exports and imports, respectively. Among the imported goods from China, machinery and apparatus (39.0%) and manufacturers of metals (7.1%) are the two largest categories. Given the large size of the Sweden-China trade, trade with China will likely influence the Swedish labor market, particularly employment in the manufacturing sector.

Figure A1 in the appendix displays the Swedish manufacturing employment and the total import/export between China and Sweden during 1996–2012 from the OECD database.

To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies have explored the employment effect of import shocks from China on the Swedish labor market. Sweden is an interesting country to study the effects of trade shocks in the labor market as the size of the manufacturing industry, in terms of GDP percentage, is similar to that of the United States. However, its labor market differs from that of the United States in many features related to institutional settings and the skill composition of the labor force (according to World Bank data, manufacturing was approximately 13% and 12% of GDP in 2016 for Sweden and the United States, respectively. See the studies of Adermon and Gustavsson [

16] and Anxo [

17] for the discussion of skill upgrade and job polarization in Sweden during the last two decades). Specifically, the institutional setting of the Swedish labor market is characterized by a strong influence of unions, a centralized wage bargaining system, a high level of employment protection, and generous unemployment benefits that include several labor market programs. The Swedish population has experienced a clear education and skill upgrade during the last two decades [

17]. Low-skilled workers are known to be vulnerable in the labor market under new technology and trade, and Sweden has adequately dealt with the role of technology and globalization through labor policy intervention [

18]. In 1997, Sweden launched an adult education program called ‘Knowledge Lift’ to enhance the skill levels of low-skilled workers. During 1997–2000, approximately 10% of the labor force participated in the program [

19].

Furthermore, the increasing import trade competition from low-income countries has also raised concerns about the income of wage earners in high-income countries [

10]. Compared to other developed countries, Sweden has a high union rate and a considerably high coverage of collective agreement. According to the Swedish National Mediation Office, approximately 90% of wage earners are covered by the collective agreement. Non-union workers may also be covered by the collective agreement. Previous research has shown that the influence of international trade on wages is also related to whether workers are covered by the collective agreement [

20]. Some studies have examined the impact of increased import competition from China on the average wage earnings growth [

21,

22]. However, the average wage earnings growth is not informative about how trade affects workers at various levels of the wage earnings distribution. Therefore, in this study, we also try to contribute to the growing literature on the effect of trade shocks on earnings, emphasizing the distributional earnings effect.

In this context, it is worth investigating whether the increasing import competition from China would affect employment and earnings distribution in a welfare state like Sweden. Therefore, we contribute to the active literature on the labor market effects of increasing import competition from low-income countries in high-income countries. Using the high-quality employment and earnings data from the Population Register from Statistics Sweden (

https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/trade-in-goods-and-services/ (accessed on 2 February 2022)) during 1996–2007, we investigate the effect of increasing import shocks from China on employment and wage distribution (Our research study is based on population-wide register data from Statistics Sweden and trade data from the UN Comtrade Database (

https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2022)) for 1996–2007). When investigating the employment effect, we employ the methodology of Autor et al. [

15], which relies on the construction of a labor market index subject to trade shocks. The advantage of the implemented methodology lies in its analytical design, which enables the investigation of the causal effects of trade shocks on manufacturing sector employment and the indirect impact of trade shocks on employment outside the manufacturing sector. To investigate the effects of import shocks from China on the earnings distribution, we follow a two-step quantile regression method recently developed by Chetverikov et al. [

22].

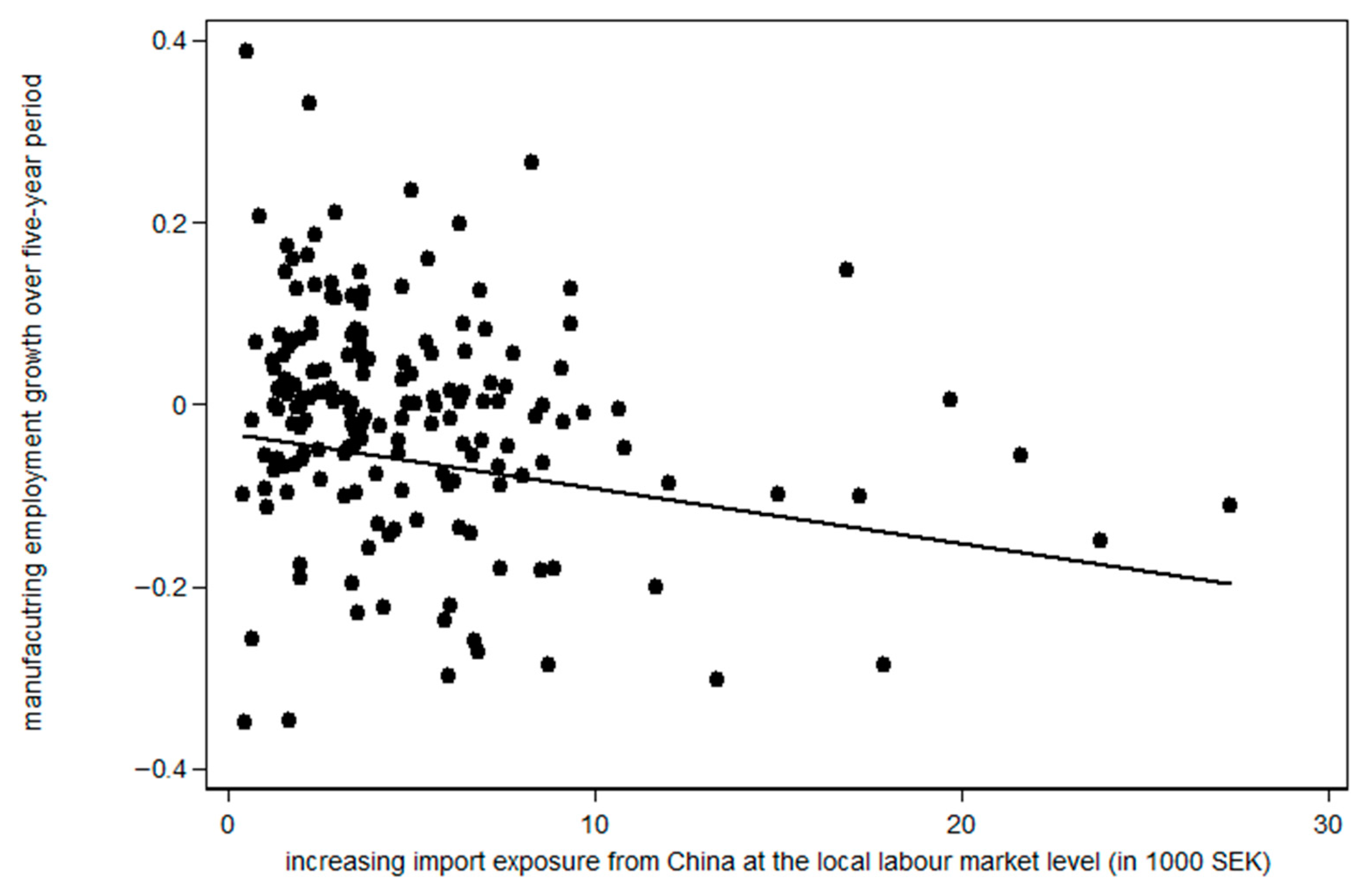

Our main research contribution to the relevant literature stems from the original findings, which state that the impact of increasing import exposure to China on the Swedish manufacturing and non-manufacturing employment growth is statistically insignificant, except for the transportation sector. Regarding earnings distribution, we find that the earnings growth of low-wage earners in the manufacturing sector is not significantly influenced by an increase in Chinese imports. However, wage earners at the median level or above are positively impacted by trade shocks from China. These findings are important to policymakers who regulate the labor market because a high unionization rate, uniform pay increments within the industry, and a centralized wage bargaining system are considered a means to protect the domestic labor market from import competition by low-income countries. Our study also appears to be the first to investigate the effect of trade shocks from China on the Swedish labor market.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a review of the literature on the international trade and labor market. Further,

Section 3 explains the dataset used and the methodology implemented in the analysis. Moreover,

Section 4 discusses the empirical results, and

Section 5 explains the empirical results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

The theoretical motivation to measure the effect exerted by international trade on a local labor market stems from the studies conducted by Wood [

23] and Autor et al. [

15,

24]. They argue that the exogenous shock of a global economic factor, such as international trade, would affect regional economies in developed countries through two channels: export supply, and import–demand shocks. The export-supply shock from the low-income country reduces the demand for labor force in the industry exposed to trade in the high-income country. The labor force is expected to flow from the sector exposed to international trade to other sectors not exposed to this trade or go into unemployment. Under the import-demand shock, import demand would be expected to increase high-income countries’ regional wages and employment on the traded sector. The labor force is expected to flow from the sectors not engaged in international trade to those involved in it or opt for unemployment. They also demonstrate that increasing import competition from China leads to large negative effects (e.g., unemployment) on regional labor markets concentrated in the manufacturing sector and the cumulative earnings of low-skilled workers. However, the size of the effect is weaker among high-skilled workers. Other studies from Spain [

25] and France [

26] have arrived at similar findings—the manufacturing sector’s labor force is the most affected by Chinese import competition.

Studies from Northern European countries have revealed mixed evidence regarding the impact of increased Chinese import competition on manufacturing sector workers’ wages. The magnitude of the import trade’s impact on manufacturing employment in these countries is even smaller [

21,

26,

27]. Bilici [

26] shows that a Chinese import shock has little impact on the UK manufacturing labor market employment and wages. The study by Dauth et al. [

27], within the Eastern European context, identifies a negative effect on local labor markets resulting from the trade with Eastern European countries rather than China. Balsvik et al. [

21], using data from Norway, indicate that increasing import exposure from China negatively affects manufacturing employment. However, the estimated effect is quantitatively much smaller than that identified by Autor et al. [

15]. Balsvik et al. [

21] do not find any negative impact on earnings, which they attribute to Norway’s centralized wage bargaining. Using Danish employer–employee data from 1995 to 2007, Utar [

28] finds that increasing the import of Chinese textile products has a negative employment effect in the Danish textile and clothing industry. Furthermore, the study finds that firms react to the Chinese competition by moving away from China’s more competitive products and becoming more skill-oriented. Baziki [

29] finds that the rise of Chinese import penetration significantly increases the earnings of high-skilled workers, probably due to the upgrade of a firm’s production technology, in response to the competition from low-income countries, which, in turn, creates a demand for skilled workers. However, that study does not find strong evidence supporting the negative effect of Chinese increasing import penetration on the earnings of low-skilled workers. Baziki et al. [

30] show a trade-induced skill upgrade in the Swedish information and communication technologies sector. Blyde et al. [

4] investigate how local labor markets in Mexico adjusted in response to an increase in Chinese import competition. They reveal that the negative employment influence was more severe on production workers than on nonproduction workers, implying that workers with lower skills were more severely influenced. Liang [

6] examines the effect of trade shocks on US manufacturing employment. The study shows that job creation obtained from the exports to different markets is comparable to the job destruction attributed to the import competition from China. Citino and Linarello [

10] examined the influence of increased import competition from China on the Italian manufacturing labor market. They reveal that workers initially employed in more exposed industries did not suffer long-term losses in terms of lower earnings or more discontinuous careers. Lang et al. [

11] analyze the effects of Chinese import exposure in the US. They discover that average mental, physical, and general health worsens in local labor markets exposed to greater import competition.

5. Possible Explanations and Robustness Checks

The insignificant employment effect on the Swedish labor market may also be explained by the fact that Sweden had already begun importing goods from other low-income countries, such as Eastern European countries. In fact, Savvidou [

37] identifies that China and Eastern European countries are the two major low-income sources for Swedish imports. To test this explanation, we consider Swedish imports from Eastern European countries (including Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, and Russia) between 1996 and 2007. We implement the same index methodology described in

Section 4. Furthermore, similar to Dauth et al. [

27], we calculate the instrument variable for Swedish imports from Eastern European countries and China by the import flows of the following countries: Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK (One of the reasons to exclude the imports from Nordic and other continental European countries in the instrument is due to the high correlation for the unobserved demand and supply shock among Sweden and those countries [

27]). We first show the effect of import exposure from Eastern countries in column 1 of

Table 5, where Eastern countries include both China and Eastern European countries. The estimated coefficient is approximately 0.001, which is statistically insignificant. In columns 2 and 3, we examine the effects from Eastern European countries and China separately (The estimated coefficient in column 3 of

Table 5 is different from the baseline result in column 7 of

Table 2 because we use fewer countries to construct the instrument variable in the former). Our regression results show that neither the rise of imports from Eastern European countries nor that from China have had any significant effect on the five-year growth of manufacturing employment. Thus, we argue that the rise of Eastern European countries is less likely to explain the insignificant labor market influence of increasing import competition from China.

Previous literature has also identified that the increasing import competition from low-income countries can induce firms in high-income countries to upgrade their product quality and invest more in technology [

38,

39]. If Swedish firms have anticipated their rising exposure to globalization, especially the competition from low-income countries, firms would likely adjust their product portfolio, for instance, through innovation, to differentiate from the imported foreign goods. Sweden is known as one of the most innovative countries in Europe [

40]. However, due to the lack of firm-level data, it is not possible to directly test whether more innovated firms are less likely to downsize. Other studies, such as that of Hombert and Matray [

41], have shown that research and development (R&D) intensive firms are more resilient to trade shocks from low-income countries by performing product differentiation. Hombert and Matray [

41] show that manufacturing firms in the United States at the 25th percentile of the R&D distribution experience a significant employment reduction when facing import competition from China. However, trade does not affect firms in the 75th percentile of the distribution. Therefore, the stock of innovation can be one factor that explains why the Swedish labor market is not affected by the increasing import competition from low-income countries.

Just as increasing import exposure from low-income countries may lead to negative consequences on regional employment in high-income countries, increasing Swedish exports to low-income countries would boost the regional economy, which may have a positive influence on the local labor market. Thus, in this section, we test the role of increasing Swedish exports to China on manufacturing employment. Additionally, we conduct several robustness checks on the baseline results. These results are available upon request.

In analyzing the net effect of trade on employment, it is important to consider exports. Along with Bilici [

26] and Dauth et al. [

27], we construct an index that measures the increase in Swedish export exposure to China at the local labor market level. Following

Table A2 in the appendix, the estimated result from column 2 shows that the expansion of Swedish exports to China by SEK 1000 would increase the growth of local manufacturing employment by 0.9 percentage points. In assessing the endogeneity, we use the increase in other high-income countries’ exports to China as the instrument variable for the increase in Swedish exports to China. However, the instrument variable could not pass the relevance test. The F-statistic for the export variable from the first-stage regression is below 10, which questions the instrument’s strength. Therefore, the extent to which the increase in export exposure to China would benefit Swedish employment is uncertain because the estimated coefficients from OLS are likely to be biased. One possible explanation for the weak instrument is that exported goods from advanced countries to China are fairly diversified across high-income countries compared with Chinese exports to advanced countries, which are primarily labor-intensive manufactured goods. Although we cannot measure the impact of exports on the labor market, it may be important to control export competition to investigate the import effect on manufacturing employment and earnings growth.

Table A3 in the

Appendix A shows that the conclusion is robust to the inclusion of export competition in the model specification.

In the previous sections, we investigated the effect of trade-induced shocks from China on manufacturing employment growth. However, trade effects likely vary for different demographic groups. We further explore the effect of trade on manufacturing employment by education and age groups. The education group is classified as follows: university, secondary school, and elementary school. The age group is classified into three: 16–34, 35–50, and 51–64. Again, we cannot find any strong evidence indicating that increasing import competition from China has a significant effect on manufacturing employment growth. Additionally, we find that increasing import penetration from China has insignificant effects on the change in the working-age population at the local labor market level. These findings are shown in

Table A4 and

Table A5 in the

Appendix A.

A possible explanation to these results is that the imports from China include the final and intermediate goods, which can be processed and sold. If the increasing imports is mainly due to intermediate goods, it may raise the firm’s productivity as revenue increases. Therefore, firms may increase the labor demand, which would partially offset the increasing import competition effect from final goods. To address this issue, we attempt to distinguish between final and intermediate goods. We follow other studies using the input-output table from Statistics Sweden. Unfortunately, the input–output table is only available for 1995, 2000, and 2005. Therefore, we take the data from these years as a proxy for the 1996, 2001, 2002, and 2007 data. We use the share of Swedish imports of final goods from the world as a proxy for the imports of final goods from China. The regression results are presented in

Table A6 in the

Appendix A. The results indicate that the increasing import exposure of final goods from China does not significantly influence the growth of manufacturing employment. However, the result must be interpreted with caution as we use the share of Swedish imports of final goods from the world as a proxy for the share from China, where the share is based on final goods from both high- and low-income countries.

The literature on job offshoring and skill-biased technical change demonstrates that routine-intensive tasks are more easily offshored to other countries or replaced by technology than non-routine tasks [

15,

42], which contributes to the decline of manufacturing employment in developed countries. Therefore, local economies that initially have high routine-intensive employment are more likely to see a reduction in employment. To address this factor, we construct a variable that measures the percentage of routine-intensive occupations for each local labor market. To measure the intensity of routine tasks for each occupation, we use the shares from a previous Swedish study by Hakkala et al. [

43]. The variable of the share of routine occupation in the local labor market ranges from zero to one, where zero means the local labor market has the lowest share of routine-intensive occupations, and one means the local labor market has the highest. As our occupation data are only available from 2001 onwards, we restrict our empirical investigation to the second period (2002–2007). The regression results from

Table A7 in the

Appendix A reveal that adding the control of the percentage of routine occupations hardly affects the estimation of our variable of interest.

6. Conclusions

Trade frictions between countries intensify, tariff barriers rise, and retaliatory tariffs are frequently imposed. Free trade is shrinking and protectionism is strengthening. These recent trends threaten the sustainability of the international trade order.

Over the past few decades, the growth in Chinese exports has dramatically changed world trade patterns. As shown in previous literature, the large inflow of Chinese products has had a substantial negative effect on the labor markets in some high-income countries [

15]. Furthermore, research has shown that the labor market effect of trade shocks from low-income countries on high-income countries also depends on the institutional setup of the labor market [

20,

26]. The institutional setup and features of the Swedish labor market differ from those of many other European countries and the United States. Thus, it is important to understand the Swedish labor market’s reaction to increasing import competition from low-income countries such as China. In this study, we apply the methodologies of Autor et al. [

15], which rely on the construction of a regional labor market index subject to trade shocks to investigate whether the effect of international manufacturing imports from China on the Swedish labor market (i.e., manufacturing, and non-manufacturing employment growth and wage earnings distribution) is statistically significant.

The empirical results indicate that the impact of increasing import exposure to China on Swedish manufacturing employment growth is statistically insignificant. We further rule out the explanation that Sweden had already begun importing goods from Eastern European countries before the rise in imports from China. The insignificant employment effect contradicts findings from other developed countries [

15,

25,

26]. One explanation is that, relative to the larger effect of the Chinese supply shock in the US labor market, for instance Autor et al. [

15], China’s supply shock on the Swedish labor market might be too small to be able to generate any significant employment effect. Furthermore, the employment adjustment may occur at the intensive rather than the extensive margin, which requires further exploration. Our findings on employment also differ from the previous findings from the neighboring country, Denmark, where Utar [

28] shows a negative employment effect in the textile industry in Demark due to the rise of Chinese competition. One possible explanation for the different findings may be related to the level of innovation, technological advancement, and the specialization of products among Swedish firms are different from those among Danish firms, in which the level of innovation in Sweden is considered to be high [

40]. For example, to deal with the foreign competition, the Swedish textile industry was reconstructed in the 1970s and has since become extremely focused and specialized according to the 2015 report from the Swedish trade and employer’s association for companies in the textile and fashion industry [

44]. Hence, one way to survive in the increasing competition from low-income countries, as suggested by Hombert and Matray [

41], is to differentiate domestic products from imported goods through quality upgradations. Furthermore, our finding is also similar to that of Balsvik et al. [

21], who show a modest employment effect from Norway due to the competition from China.

Regarding the wage earnings distribution, our research results indicate that the earnings growth of low-wage earners in the manufacturing sector is not significantly influenced by increases in Chinese imports. However, wage earners at the median level or above are positively affected by trade shocks from China. This is in line with the studies of Baziki [

30] and Balsvik et al. [

21], who find that skilled workers are positively influenced by import shocks from China. Owing to the high coverage of collective agreement, wage earners at the lower percentile of the earning distribution are less likely to be influenced by the increase in import penetration from low-income countries. Furthermore, the results also suggest that imports from China might be complementary to median- or higher-wage earners who are more skilled. The findings imply that the increasing import competition from low-income countries could potentially widen the income gap between low- and high-wage workers.

Given the response of the Swedish labor market to trade shocks from China, labor market factors such as a high participation rate of union and collective agreement may likely help deter the negative impact of trade shocks on employment and earnings growth. However, continuous investment in human capital and the R&D of firms can also play a role when faced with an increase in import competition from low-income countries [

45]. These policies can enhance the sustainability of the beneficial trade between Sweden and China.