How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Hybrid Organizations and Social Enterprises

2.2. Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability

2.3. Circular Economy and Social Sustainability

2.4. Circular Economy and Encyclical “Laudato Si’”

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Empirical Setting

3.2. Data Collection

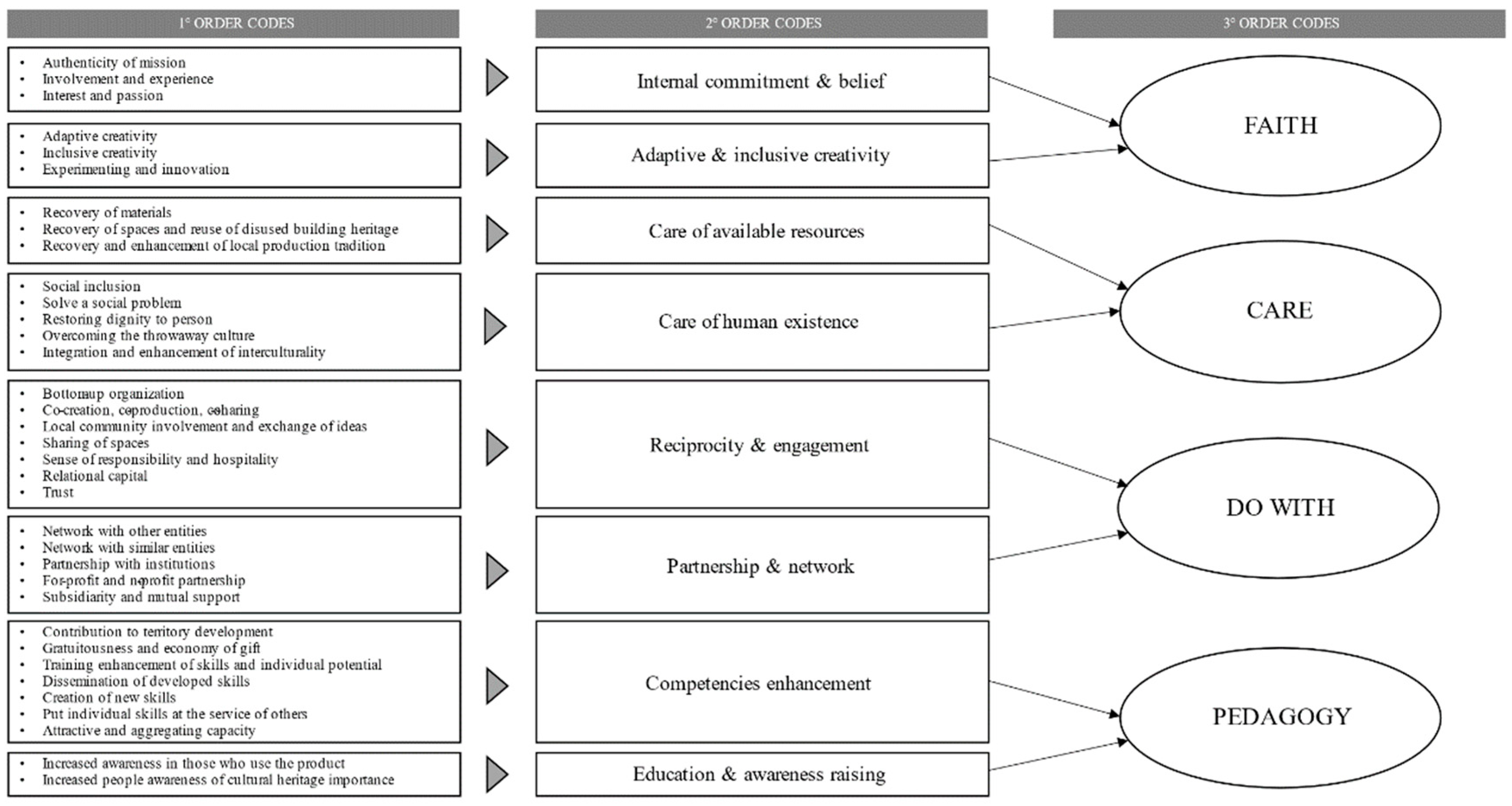

3.3. Data Analysis

- Step 1:

- Open Coding

- Step 2:

- Axial Coding

- Step 3:

- Building a Grounded Model

4. Results

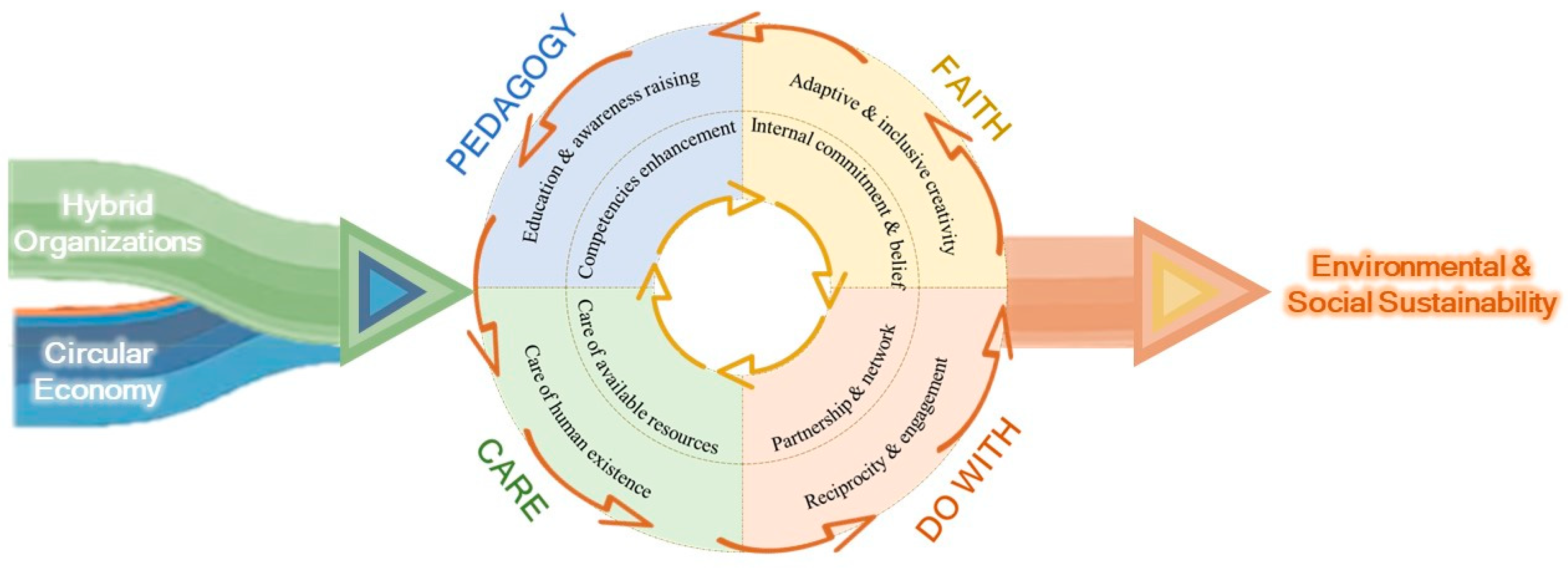

4.1. Faith

“You work within a complex system; for that reason, you must be stubborn, convinced of your value, of what you do. You’ll have to deal with any kind of person. [...] Evidently, it is difficult. I think it takes determination and awareness of what you represent and of your importance. [...] Who works with you must understand who you are and choose to embrace your project”(Firm #1).

“Suppose we have to buy a lace; our corporate ethic forces us not to include that lace [in the final product]; we have to adapt the design according to what we already have, or we can collect”(Firm #4).

“It is not true that a boy is not able to perform a certain activity. If you adapt the context or the procedure, that boy will be able to perform the activity, and he will surprise you!”(Firm #6).

4.2. Care

“There was frustration. We looked around to understand what opportunities of practical work we could provide to people who stayed in the reception centers for long.”

“I had the strong desire to set up a business and challenge the cooperative concept. At the regulatory level, according to the law of 1991, the target of cooperatives B is disadvantaged groups. So, it is a very specific category. However, in my opinion, our society is a living society; it’s moving, it’s changing, it’s not enough to take a picture of the society in 1991 and pretend that it is still the same. [...] Setting up a social enterprise meant assuming responsibility, taking care, reflecting upon people who may have difficulty—even just for a limited period of their life—and they need to be supported and enhanced. I have always been afraid of the idea that the label “disadvantaged” is a lifelong label. I cannot deal with people who will be classified forever as ’disadvantaged.’ This is a journey; the journey must be appreciated. It is our task to take care of these people and give them a chance to ’climb a step’ and improve their life perspective.”

4.3. Do With

“Customers live an experience on-site, and this enables them to build a relationship that gives the impression of care, of being part of a pattern of an inclusive and cohesive society”(Firm #5).

4.4. Pedagogy

“Our way of conceiving an object is that it should be an ‘educational’ object. It means that it should communicate to people who are buying it that they are not creating any impact on the environment. The value of the object corresponds to the awareness raised among its consumers and producers. [...]. This is the educational role of our project: to communicate how each one of us can make his own decisions. Here is our power to change things, also at a political level, starting from what we choose to eat, to buy, not to buy…”

“The objective is relating with customers not only as “consumers” but as supporters, believers of the project.”

“Our wish is to put people at the center of our project; we try to bring out their already-acquired craft skills along with the capability to cooperate and work together”(Firm #4).

“We do not have to be afraid of using the word ‘selection’; otherwise, we will make wrong decisions and placements. We have to figure out the potentialities of each person and let them do what they are capable of doing best, and it is our job to show this also to the individual himself.”

“We have founded [the company] to provide qualified technical training through an experimental approach based on passion and care. This way, you may experience a transformative ’give and take,’ you do what you do for its generativity, not only for emotivity or compassion. Through your professionality, you restore dignity [to your fragile employees], and dignity is the cure”(Firm #5).

4.5. A Grounded Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Contribution

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- Could you describe the business model of your organization?

- What is the mission of your organization? What is the ultimate goal of the activities carried out by the organization itself?

- When and how did you develop the idea of this project?

- What need do you seek to satisfy?

- How has the project evolved since it began?

- Which is the legal form of your organization (e.g., profit, nonprofit, cooperative)?

- 7.

- Do you think yours is a generative project?

- At the economic level:

- Has the project generated profits?

- At the socio-cultural level:

- b.

- Has your organization been welcomed by the local community? Which kind of relationship have you established with the local community? Has it been involved in your decision process somehow?

- c.

- How do you enhance the inclusion of disadvantaged people in your organization? How do you foster different forms of cooperation and social inclusion?

- d.

- Has the project created jobs? If so, how many (approximately)? How many employees do you have? How many of them are full-time employees and how many are part-time?

- e.

- How many volunteers are involved in your organization?

- f.

- Has your project, according to you, generated some of the following impacts: increased the awareness of cultural heritage, the sense of belonging, social cohesion, the inclusion of marginalized groups, enhanced cultural activities, the personal well-being of inhabitants, workers and end users, etc.?

- At the environmental level:

- g.

- How do you take into consideration your environmental impact (e.g., working with waste, biological raw materials, energy efficiency, recovery and recycling, digital technologies for circularity, etc.)?

- h.

- Do you think you have contributed to the enhancement of the environmental quality at the local level? If so, in which way?

- 8.

- Do you think yours is a regenerative project?

- At the economic level:

- Do you reinvest the profits of the organization? If so, in which kinds of activities?

- Has your project led to the restoration or regeneration of the economic context in which the organization is located (e.g., increasing the number of new business activities)?

- At the socio-cultural level:

- c.

- Who are, according to you, the primary stakeholders of your organization? Has the project restored a sense of confidence in these and other potential stakeholders? How do you judge your relationship with them?

- d.

- Does the project contribute to a regeneration of reciprocity in relations with other entities? Has the project led to the development of different forms of partnership or mutual cooperation?

- e.

- Do the activities carried out by the organization actively involve people, leading to the regeneration of intellectual capital and increasing their knowledge and competences?

- At the environmental level:

- f.

- Has the project led to the development or regeneration of natural capital (e.g., green areas)?

- 9.

- Do you think yours is an autopoietic project?

- At the economic level:

- Is your organization self-sufficient in terms of financial sustainability over the long term (e.g., it does not depend on external financing)? If so, when and how did you achieve this economic independence? What form of funding has made it possible to start the project? What form of funding currently financially supports the project?

- At the environmental level:

- b.

- Have you adopted any measure or technology that makes your organization self-sufficient in terms of resource consumption (i.e., that limits the consumption of non-renewable resources in terms of energy sources, raw materials, etc.)?

- 10.

- Could you identify the critical success factors of your project?

- 11.

- Could you identify the obstacles and the limitations that could prevent your project from continuing over the long term?

References

- Nesterova, I. Degrowth business framework: Implications for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, H.; Lindgreen, A. Sustainability, Epistemology, Ecocentric Business, and Marketing Strategy: Ideology, Reality, and Vision. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa Francesco. Lettera Enciclica Laudato Sì del Santo Padre Francesco sulla Cura della Casa Comune; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Roma, Rome, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Cohen, M.; Dewick, P.; Hofstetter, J.; Sarkis, J. Degrowth within—Aligning circular economy and strong sustainability narratives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Wandosell-Fernández-de-Bobadilla, G. The Main Research Characteristics of the Development of the Concept of the Circular Economy Concept: A Global Analysis and the Future Agenda. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L. Critique of Managerial Reason. Humanist. Manag. J. 2021, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klikauer, T. Managerialism; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-349-46267-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Human-Centred City: Opportunities for Citizens through Research and Innovation; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, V.M.; Martínez, G.L. Constitutional profiles of the encyclical letter “Laudato Si”: An analysis from economic anthropology. Rev. Direito Bras. 2018, 20, 364–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. Accelerating the Scale-Up across Global Supply Chains; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, R.M.; Labella, Á.; Nuñez-Cacho, P.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Martínez, L. A comprehensive minimum cost consensus model for large scale group decision making for circular economy measurement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. The circular economy in transforming a died heritage site into a living ecosystem, to be managed as a complex adaptive organism. Aestimum 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Model, J. Harnessing Productive Tensions in Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Work Integration Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, S.; Morales, A.; Calvo, S.; Molina Moreno, V. Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory. Sostenibilidad 2021, 13, 13408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, J. Navigating Paradox as a Mechanism of Change and Innovation in Hybrid Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. Hybrid Organizations: The Next Chapter in Sustainable Business. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 41, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pieroni, M.P.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Circular economy business model innovation: Sectorial patterns within manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. GREEN PAPER: Promoting An European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, B. Maximizing shareholder-value: A panacea for economic growth or a recipe for economic and social disintegration? Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2008, 4, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Petty, W.; Wallace, J. Shareholder Value Maximization-Is There a Role for Corporate Social Responsibility? J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2009, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, M.J.P.; Quinzii, M.; Rochet, J.-C. A Critique of Shareholder Value Maximization. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Grimes, M.; McMullen, J.; Vogus, T. Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. When Worlds Collide: The Internal Dynamics of Organizational Responses to Conflicting Institutional Demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic equilibrium Model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharov, M.L.; Smith, W.K. Multiple Institutional Logics in Organizations: Explaining Their Varied Nature and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, S.; Bernard, S.; Sloan, P. Environmental sciences, sustainable development and circular economy: Alternative concepts for trans-disciplinary research. Environ. Dev. 2016, 17, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S. Towards Circular Business Models: A systematic literature review on classification frameworks and archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.M.; Opferkuch, K.; Roos Lindgreen, E.; Simboli, A.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Raggi, A. Assessing the social sustainability of circular economy practices: Industry perspectives from Italy and the Netherlands. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mies, A.; Gold, S. Mapping the social dimension of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumparou, D. Circular Economy and Social Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Solid Waste Management & its Contribution to Circular Economy, Athens, Greece, 14–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A. Circular economy and cultural heritage/landscape regeneration. Circular business, financing and governance models for a competitive Europe. BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2017, 17, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Manninen, K.; Koskela, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bocken, N.; Dahlbo, H.; Aminoff, A. Do circular economy business models capture intended environmental value propositions? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijkman, A.; Skånberg, K. The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society: Jobs and Climate Clear Winners in an Economy Based on Renewable Energy and Resource Efficiency. Club Rome 2015, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bannick, M.; Goldman, P.; Kubzanksky, M.; Saltuk, Y. Across the Returns Continuum. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2018, 15, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.E. The relationship of urban design to human health and condition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 64, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, S.; Ratha, D. Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes; Word Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Dembek, K. Sustainable business model research and practice: Emerging field or passing fancy? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, V. Bringing Social Impact into Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.boardofinnovation.com/blog/bringing-social-impact-into-circular-economy/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business cases for sustainability: The role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation, E.M. Towards the Circular Economy: Economyc and business rationale for accelerated transition. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morseletto, P. Restorative and regenerative: Exploring the concepts in the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; De Rosa, F.; Nocca, F. Verso il piano strategico di una città storica: Viterbo. BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2014, 14, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Angrisano, M.; Biancamano, P.F.; Bosone, M.; Carone, P.; Daldanise, G.; De Rosa, F.; Franciosa, A.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S.; Nocca, F.; et al. Towards operationalizing UNESCO Recommendations on “Historic Urban Landscape”: A position paper. Aestimum 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. The Cultural Base of Cities for Shaping a Better Future. In Proceedings of the International Meeting New Urban World Future Challenges, Rabat, Maroc, 1–2 October 2012; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ravetz, J.; Fusco Girard, L.; Bornstein, L. A research and policy development agenda: Fostering creative, equitable, and sustainable port cities. BDC Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2012, 12, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, F.; Böhm, S. Against wasted politics: A critique of the circular economy. Ephemer. Theory Polit. Organ. 2017, 17, 23–60. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU action plan for the Circular Economy—(ANNEX 1). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. 2015. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2015-0614-final (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Moreno, M.; De los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A conceptual framework for circular design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonesio, L. Paesaggio, Identità e Comunità Tra Locale e Globale; Diabasis: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karpoff, J.M. The Tragedy of ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’—Hardin vs. the Property Rights Theorists. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.M. Thinking about the commons. Int. J. Commons 2020, 14, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. 1990. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/governing-the-commons/7AB7AE11BADA84409C34815CC288CD79 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Sacconi, L.; Ottone, S. Beni Comuni e Cooperazione; Il Mulino: Macao, 2015; ISBN 978-8815253767. Available online: https://www.mulino.it/isbn/9788815253767 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Schlager, E. Rationality, cooperation, and common pool resources. Am. Behav. Sci. 2002, 45, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santori, P. Is Relationality Always Other-Oriented? Adam Smith, Catholic Social Teaching, and Civil Economy. Philos. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Applying Grounded Theory. In The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies of Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 1967; Volume 13, Available online: http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Scarlato, M. Social Enterprise and Development Policy: Evidence from Italy. J. Soc. Entrep. 2012, 3, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Musella, M. L’Impresa Sociale in Italia. Identità e Sviluppo in un Quadro di Riforma; Iris Network Istituti di Ricerca Sull’Impresa Sociale: Trento, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ranci, C. The third sector in welfare policies in Italy: The contradictions of a protected market. Voluntas 1994, 5, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, H.G.; Miles, M.B.; Michael Huberman, A.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook. Z. Fur Pers. 2014, 28, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. From the Editors: For the Lack of a Boilerplate: Tips on Writing Up (and Reviewing) Qualitative Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, W.M.; McNulty, R.E. Transforming faith in corporate capitalism through business ethics. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2012, 9, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Wang, J. Spiritual leadership: Current status and Agenda for future research and practice. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2020, 17, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lim, U. Social Enterprise as a Catalyst for Sustainable Local and Regional Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, L.; Demartini, P.; Marchegiani, L.; Marchiori, M.; Piber, M. Understanding orchestrated participatory cultural initiatives: Mapping the dynamics of governance and participation. Cities 2020, 96, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, M.; Jonas, A.E.G.; Deutz, P. Circularity as Alterity? Untangling Circuits of Value in the Social Enterprise–Led Local Development of the Circular Economy. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 97, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvini, A.; Riccardo, A.; Vasca, F.; Psaroudakis, I. Inter-Organizational Networks and Third Sector: Emerging Features from Two Case Studies in Southern Italy. In Challenges in Social Network Research; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2020; pp. 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovich, K.; Doyle Corner, P. Spiritual organizations and connectedness: The Living Nature experience. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2009, 6, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D. “Human Quality Treatment”: Five Organizational Levels. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, M. Caring Management in the New Economy, socially Responsible Behaviour Through Spirituality. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2020, 17, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quélin, B.V.; Kivleniece, I.; Lazzarini, S. Public-Private Collaboration, Hybridity and Social Value: Towards New Theoretical Perspectives. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 763–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, J.G.; Stead, W.E. Building spiritual capabilities to sustain sustainability-based competitive advantages. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2014, 11, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. La rigenerazione del “Sistema Matera” nella prospettiva dell’economia circolare. In Matera, Città del Sistema Ecologico Uomo/Società/Natura il Ruolo Della Cultura per la Rigenerazione del Sistema Urbano/Territoriale; Fusco Girard, L., Trillo, C., Bosone, M., Eds.; Giannini Publisher: Naples, Italy, 2019; pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti, L.; Bruni, L.; Zamagni, S. Economia Civile e Sviluppo Sostenibile. Progettare e Misurare un Nuovo Modello di Benessere; Ecra Editore: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| # | Industry | Firm Description | Special Feature | Location | Job Role Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manufacturing | Social enterprise producing accessories made of leather and fabric | Recovery of secondary raw materials; craft training for migrants and asylum seekers for employment | Bologna | President |

| 2 | Management of a historic site | Cooperative born to restore and manage a historic site in a problematic area of the city | Enhancement of artistic and cultural heritage and strong civil participation | Naples | Marketing Director |

| 3 | Agriculture and accommodation | Rehabilitation and employment of people with disabilities | Organic farming; territorial and human valorization | Perugia | President |

| 4 | Manufacturing | Social enterprise producing tools and accessories from recycled materials and organizing craft workshops | Up-cycling and cultural exchanges; craft training for migrants and asylum seekers | Lucca | President |

| 5 | Tailoring | Social enterprise producing tailor-made suits | Recovery of secondary raw materials cultural exchanges; empowerment of migrant women | Turin | CEO |

| 6 | Retail | Store selling past- season items of well-known brands and employing people with disabilities | Social inclusion and employment opportunities for vulnerable people | Como | CEO |

| Data Source | Type of Data | Use in the Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Public documents | Press release | Familiarization with the business ecosystem and purpose |

| Website contents | ||

| Social media channels | ||

| Interviews | Semi-structured interviews | In-depth understanding of topic of interest |

| Enterprise documents | Business models | Supporting, integrating, and triangulating evidence from the interviews |

| Business plans | ||

| Internal documents |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaccone, M.C.; Santhià, C.; Bosone, M. How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052679

Zaccone MC, Santhià C, Bosone M. How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052679

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaccone, Maria Cristina, Cristina Santhià, and Martina Bosone. 2022. "How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052679

APA StyleZaccone, M. C., Santhià, C., & Bosone, M. (2022). How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 14(5), 2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052679