Validation and Factorial Invariance of the Life Skills Ability Scale in Mexican Higher Education Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Instrument

2.1.3. Procedure

2.1.4. Data Analysis

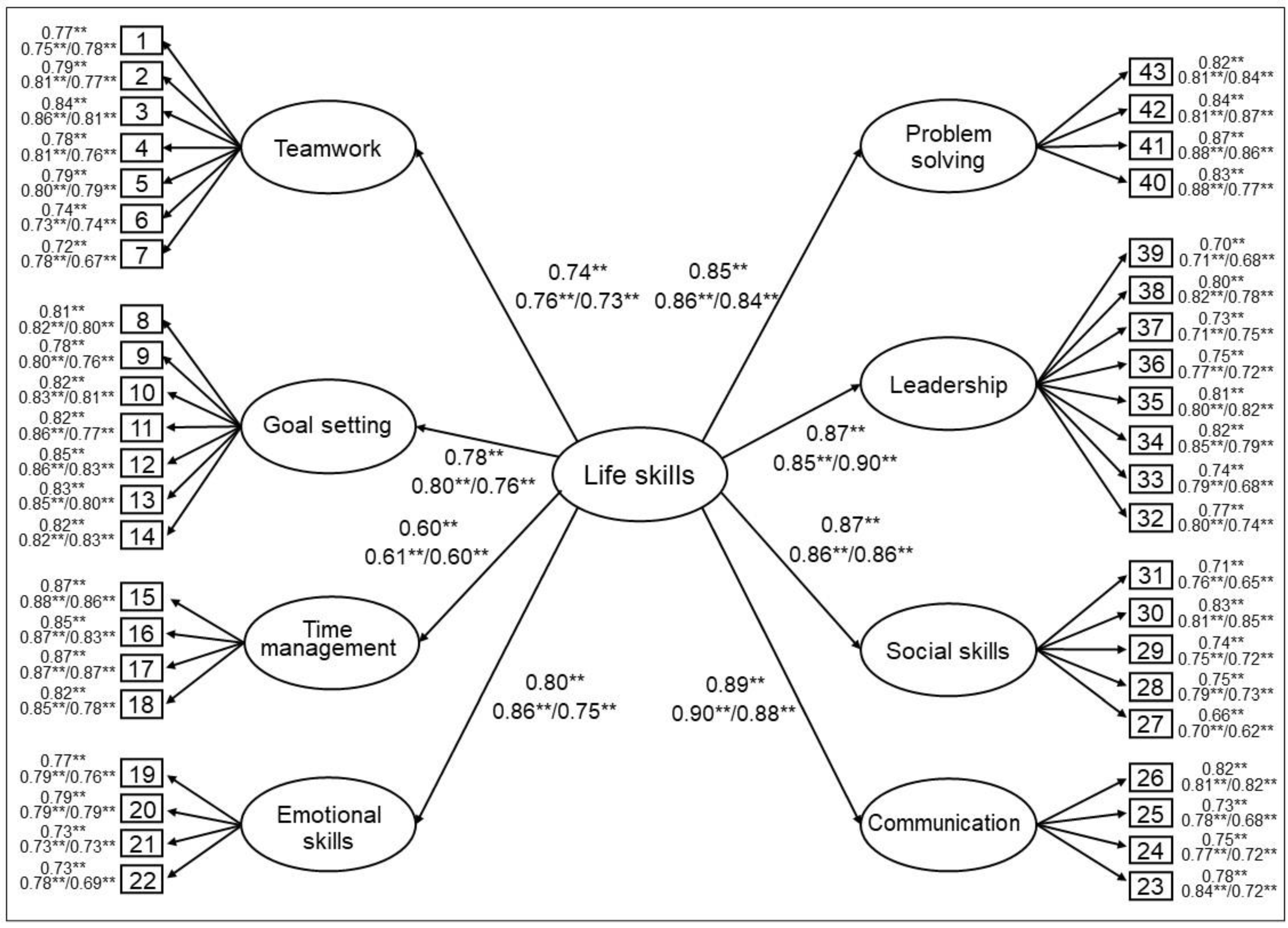

2.2. Results

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Instruments

3.1.3. Procedure

3.1.4. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

4. Overall Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cronin, L.D.; Allen, J. Development and Initial Validation of the Life Skills Scale for Sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 28, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, L.; Allen, J.; Ellison, P.; Marchant, D.; Levy, A.; Harwood, C. Development and initial validation of the life skills ability scale for higher education students. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 46, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J. Life Skills, Wealth, Health, and Wellbeing in Later Life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4354–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, A.; De la Mora, E.; Marsh, J.; Workman, H. COVID-19 and the future of work in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kang, T.; Daigo, E.; Matsuoka, H.; Harada, M. Graduate employability and higher education’s contributions to human resource development in sport business before and after COVID-19. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totskaya, N. Increasing Employability Through Development of Generic Skills: Considerations for Remote Course Delivery During COVID-19 Pandemic. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism in the COVID-19 Era; Kavoura, A., Havlovic, S.J., Totskaya, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, M.R.; Sternberg, R.; Jones, S.; Nohara, D.; Murray, T.S.; Clermont, Y. Moving Towards Measurement: The Overarching Conceptual Framework for the ALL Study. In Measuring Adult Literacy and Life Skills: New Frameworks for Assessment, 1st ed.; Murray, T.S., Clermont, Y., Binkley, M., Eds.; Minister Responsible for Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 46–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarraran, P.; Ripani, L.; Taboada, B.; Villa, J.M.; Garcia, B. Life skills, employability and training for disadvantaged youth: Evidence from a randomized evaluation design. IZA J. Labor Dev. 2014, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lowden, K.; Hall, S.; Elliot, D.; Lewin, J. Employers’ Perceptions of the Employability Skills of New Graduates; Edge Foundation: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roodt, J. Self-employment and the required skills. Manag. Dyn. 2005, 14, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. 2015. Available online: https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Organization Nations United. The Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Wolf, R.; Zahner, D.; Benjamin, R. Methodological challenges in international comparative post-secondary assessment programs: Lessons learned and the road Ahead. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Prezumic, T.; Arteche, A.; Bremner, A.J.; Greven, C.; Furhham, A. Soft skills in higher education: Importance and improvement ratings as a function of individual differences and academic performance. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, M.M. Executive Perceptions of the Top 10 Soft Skills Needed in Today’s Workplace. Bus. Commun. Q. 2012, 75, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keneley, M.; Jackling, B. The acquisition of generic skills of culturally-diverse student cohorts. Account. Educ. 2011, 20, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Virtanen, A.; Tynjälä, P. Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: A study of university students’ experiences. Teach. High. Educ. 2019, 24, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasheeda, A.; Abdullah, H.B.; Krauss, S.E.; Ahmed, N.B. A narrative systematic review of life skills education: Effectiveness, research gaps and priorities. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2019, 24, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azevedo, A.; Apfelthaler, G.; Hurst, D. Competency development in business graduates: An industry-driven approach for examining the alignment of undergraduate business education with industry requirements. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 10, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, J.; Campbell-Heider, N.; David, T.M. Positive adolescent life skills training for high-risk teens: Results of a group intervention study. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2006, 20, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maryam, E.; Davoud, M.M.; Zahra, G.; Somayeh, B. Effectiveness of life skills training on increasing self-esteem of high school students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vatankhah, H.; Daryabari, D.; Ghadami, V.; KhanjanShoeibi, E. Teaching how life skills (anger control) affect the happiness and self-esteem of Tonekabon female students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menrath, I.; Mueller-Godeffroy, E.; Pruessmann, C.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Ottova, V.; Pruessmann, M.; Erhart, M.; Hillebrandt, D.; Thyen, U. Evaluation of school-based life skills programmes in a high-risk sample: A controlled longitudinal multi-centre study. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A.; Swisher, J.D.; Vicary, J.R.; Bechtel, L.J.; Minner, D.; Henry, K.L.; Palmer, R. Evaluation of life skills training and infused-life skills training in a rural setting: Outcomes at two years. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2004, 48, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Teyhan, A.; Cornish, R.; Macleod, J.; Boyd, A.; Doerner, R.; Sissons Joshi, M. An evaluation of the impact of “lifeskills” training on road safety, substance use and hospital attendance in adolescence. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 86, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gulesci, S.; Puente-Beccar, M.; Ubfal, D. Can youth empowerment programs reduce violence against girls during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 153, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeley, M. Soft Skills. The Lingua Franca of Human Centered Management in the Global VUCA Environment. In Soft Skills for Human Centered Management and Global Sustainability; Lepeley, M., Beutell, N.J., Abarca, N., Majluf, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Espada, J.P.; Morales, A. How Super Skills for Life may help children to cope with the COVID-19: Psychological impact and coping styles after the program. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 2020, 7, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojarro, A.L.; Herrera, I.S.; Servín, L. Entrenamiento en habilidades para la vida como estrategia para la atención primaria de conductas adictivas. Psicología Iberoamericana 2017, 25, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givaudan, M.; Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Poortinga, Y.H.; Leenen, I.; Pick, S. Effects of a school-based life skills and HIV-prevention program for adolescents in Mexican high schools. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1141–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givaudan, M.; Leenen, I.; Van De Vijver, F.J.R.; Poortinga, Y.H.; Pick, S. Longitudinal study of a school based HIV/AIDS early prevention program for Mexican Adolescents. Psychol. Health Med. 2008, 13, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez de la Barrera, C. Habilidades para la vida y consumo de drogas en adolescentes escolarizados mexicanos. Adicciones 2012, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri Torres, J.C.; Hernández Herrera, C.A. Los jóvenes universitarios de ingeniería y su percepción sobre las competencias blandas. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo 2019, 9, 768–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández Herrera, C.A.; Neri Torres, J.C. Las habilidades blandas en estudiantes de ingeniería de tres instituciones públicas de educación superior. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo 2020, 10, e094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Posada, L.E.; Rosero Burbano, R.F.; Melo Sierra, M.P.; Aponte López, D. Habilidades para la vida: Análisis de las propiedades psicométricas de un test creado para su medición. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales 2013, 4, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Campas, M.A.; Ramos Santana, C.M.; Arellano Montoya, R.E.; Molina del Río, J. Propiedades psicométricas del Test de Habilidades para la Vida en una muestra de jóvenes mexicanos. Avances en Psicología 2018, 26, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in Schools; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A. A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. An approach to the use of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Partners in Life Skills Education. In Conclusions from United Nations Inter-Agency Meeting; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, C.; Neave, G. Employability deconstructed: Perceptions of Bologna stakeholders. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, A.; Solé, L.; Bernstein, S.; Lopes, M.H.; Francisconi, C.F. Cómo minimizar errores al realizar la adaptación transcultural y la validación de los cuestionarios sobre calidad de vida: Aspectos prácticos. Revista de Gastroenterología de México 2013, 78, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muñiz, J.; Elosua, P.; Hambleton, R.K. Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: Segunda edición. Psicothema 2013, 25, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lira, M.T.; Caballero, E. Adaptación transcultural de instrumentos de evaluación en salud: Historia y reflexiones del por qué, cómo y cuándo. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes 2020, 31, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joia, L.A.; Lorenzo, M. Zoom In, Zoom Out: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Classroom. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, L.A.; Sekaquaptewa, D. The influence of gender stereotypes on role adoption in student teams. In Proceedings of the 120th ASEE Annual Conference Exposition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C.; Cabanach, R.G.; González-Pineda, J.A.; Rodríguez, S.; Rosário, P.; Muñoz-Cadavid, M.A.; Cerezo, R. Academic goals and learning quality in higher education students. Span. J. Psychol. 2009, 12, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaya, H.; Kaya, N.; Palloş, A.Ö.; Küçük, L. Assessing time-management skills in terms of age, gender, and anxiety levels: A study on nursing and midwifery students in Turkey. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2012, 12, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielkiewicz, R.M.; Fischer, D.V.; Stelzner, S.P.; Overland, M.; Sinner, A.M. Leadership attitudes and beliefs of incoming first-year college students: A multi-institutional study of gender differences. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duong, M.Q.; Wu, C.L.; Hoang, M.K. Student inequalities in Vietnamese higher education? Exploring how gender, socioeconomic status, and university experiences influence leadership efficacy. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavera, C.; Usán, P.; Jarie, L. Styles of humor and social skills in students. Gender differences. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, A.; Tattersall, A.; Goody, A. Gender matters in higher education. Educ. Stud. 2020, 33, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Torres, A.P.; Ortíz-Rodríguez, V.; Narváez, M.A.; López-Walle, J.M.; Tristán, J. Análisis de las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Habilidades para la vida en su traducción al castellano. In Deporte, Educación Física y Ciencias Aplicadas; Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Organización Deportiva: Monterrey, Mexico, 2020; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Anguiano-Carrasco, C. El análisis factorial como técnica de investigación en psicología. Papeles del Psicólogo 2010, 31, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, Y.F.; Bentler, P.M. Bootstrapping techniques in analysis of mean and covariance structures. In Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques; Marcoulides, G.A., Schumacker, R.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with amos, eqs, and lisrel: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G.; Alonso, J. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Su utilidad en la validación de cuestionarios relacionados con la salud. Med. Clin. 2004, 122 (Suppl. 1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Evaluating model fit. In Structural Equation Modeling. Concepts, Issues and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating good- ness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- González Gallegos, A.G. Propuesta Metodológica para el Rediseño de la Licenciatura en Ciencias del Ejercicio de la FOD. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, San Nicolás de los Garza, Mexico, 24 August 2021. Available online: http://eprints.uanl.mx/22098/ (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Hong, J.C.; Lee, Y.F.; Ye, J.H. Procrastination predicts online self-regulated learning and online learning ineffectiveness during the coronavirus lockdown. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 174, 110673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.A. Validation of the Korean version of the obsession with COVID-19 scale and the Coronavirus anxiety scale. Death Stud. 2020, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Lirios, C. Construct validity of a scale to measure the job satisfaction of professors at public universities in central Mexico during COVID-19. Trilogía Ciencia Tecnología Sociedad 2021, 13, e1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzivinikou, S.; Charitaki, G.; Kagkara, D. Distance Education Attitudes (DEAS) During Covid-19 Crisis: Factor Structure, Reliability and Construct Validity of the Brief DEA Scale in Greek-Speaking SEND Teachers. Tech. Knowl. Learn. 2021, 26, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R. Why so few women enroll in computing? Gender and ethnic differences in students’ perception. Comput. Sci. Educ. 2010, 20, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Jaggars, S.S. Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. J. High. Educ. 2014, 85, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Sax, L.J. Student–faculty interaction in research universities: Differences by student gender, race, social class, and first-generation status. Res. High. Educ. 2009, 50, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierce, S.; Kendellen, K.; Camiré, M.; Gould, D. Strategies for coaching for life skills transfer. J. Sport Psychol. Action. 2018, 9, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S.; Gould, D.; Camiré, M. Definition and Model of life skills transfer. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 10, 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, C.; Kramers, S.; Forneris, T.; Camiré, M. The Implicit/Explicit Continuum of Life Skills Development and Transfer. Quest 2018, 70, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, A.; Mattoo, A.; Rocha, N.; Ruta, M.; Winkler, D. Pandemic trade: COVID-19, remote work and global value chains. World Econ. 2021, 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succi, C.; Canovi, M. Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: Comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1834–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambrige, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

| Study 1 (n = 525) | Study 2 (n = 707) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Skill | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α |

| Teamwork | 4.33 | 0.64 | −1.13 | 2.18 | 0.91 | 4.35 | 0.63 | −1.32 | 3.13 | 0.91 |

| Goal-setting | 4.31 | 0.63 | −0.96 | 1.78 | 0.92 | 4.29 | 0.67 | −1.14 | 2.17 | 0.93 |

| Time management | 3.88 | 0.84 | −0.63 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 3.83 | 0.85 | −0.66 | 0.59 | 0.91 |

| Emotional skills | 4.10 | 0.79 | −0.84 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 4.10 | 0.77 | −0.94 | 1.31 | 0.84 |

| Communication | 4.18 | 0.69 | −0.79 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 4.15 | 0.72 | −0.94 | 1.48 | 0.85 |

| Social skills | 4.10 | 0.75 | −0.68 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 4.07 | 0.76 | −0.79 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Leadership | 4.20 | 0.68 | −0.91 | 1.70 | 0.92 | 4.20 | 0.67 | −0.98 | 1.90 | 0.92 |

| Problem-solving | 4.22 | 0.71 | −0.89 | 1.10 | 0.90 | 4.21 | 0.70 | −0.97 | 1.55 | 0.90 |

| Total life skills | 4.18 | 0.57 | −0.98 | 2.71 | 0.97 | 4.18 | 0.57 | −1.10 | 2.87 | 0.97 |

| Life Skill | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teamwork | - | ||||||

| 2. Goal-setting | 0.61/0.62 | - | |||||

| 3. Time management | 0.46/0.36 | 0.59/0.58 | - | ||||

| 4. Emotional skills | 0.52/0.53 | 0.59/0.59 | 0.59/0.55 | - | |||

| 5. Communication | 0.69/0.52 | 0.62/0.58 | 0.52/0.47 | 0.65/0.61 | - | ||

| 6. Social skills | 0.58/0.52 | 0.57/0.51 | 0.50/0.41 | 0.57/0.52 | 0.73/0.67 | - | |

| 7. Leadership | 0.64/0.62 | 0.62/0.61 | 0.52/0.48 | 0.54/0.54 | 0.67/0.64 | 0.72/0.70 | - |

| 8. Problem-solving | 0.58/0.52 | 0.60/0.61 | 0.52/0.48 | 0.60/0.56 | 0.66/0.64 | 0.62/0.55 | 0.67/0.65 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One factor model | 5911.962 | 860 | 6.874 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 6083.962 |

| Eight factor model | 2071.336 | 832 | 2.49 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 2299.336 |

| Second order model | 2232.553 | 852 | 2.62 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 2420.553 |

| Life Skill | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teamwork | - | ||||||

| 2. Goal-setting | 0.61/0.62 | - | |||||

| 3. Time management | 0.37/0.33 | 0.60/0.56 | - | ||||

| 4. Emotional skills | 0.53/0.54 | 0.62/0.56 | 0.58/0.53 | - | |||

| 5. Communication | 0.52/0.52 | 0.58/0.58 | 0.48/0.46 | 0.65/0.59 | - | ||

| 6. Social skills | 0.49/0.53 | 0.47/0.54 | 0.40/0.43 | 0.57/0.46 | 0.75/0.58 | - | |

| 7. Leadership | 0.59/0.63 | 0.58/0.63 | 0.46/0.49 | 0.54/0.54 | 0.67/0.62 | 0.68/0.71 | - |

| 8. Problem-solving | 0.52/0.51 | 0.61/0.60 | 0.48/0.48 | 0.59/0.53 | 0.66/0.62 | 0.53/0.56 | 0.65/0.65 |

| Model | Type of Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | AIC | Δdf | p | ΔCFI | ΔIFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0a | Base model men | 1834.02 | 848 | 2.16 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.057 | 2030.02 | |||||

| M0b | Base model women | 2098.25 | 848 | 2.47 | 0.885 | 0.886 | 0.065 | 2294.25 | |||||

| M1 | Unconstrained base model | 3932.28 | 1696 | 2.31 | 0.904 | 0.904 | 0.043 | 4324.28 | |||||

| M2 | Factor load invariance | 3983.50 | 1731 | 2.30 | 0.903 | 0.903 | 0.043 | 4305.50 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| M3 | M2 + invariance intercepts | 3987.07 | 1738 | 2.29 | 0.903 | 0.903 | 0.043 | 4295.07 | 42 | 0.00 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| M4 | M3 + invariance of latent means | 3989.08 | 1739 | 2.29 | 0.903 | 0.903 | 0.043 | 4295.08 | 43 | 0.00 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| M5 | M3 + difference of latent means | 4163.26 | 1794 | 2.32 | 0.898 | 0.898 | 0.043 | 4359.26 | 98 | 0.00 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vergara-Torres, A.P.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, V.; Reyes-Hernández, O.; López-Walle, J.M.; Morquecho-Sánchez, R.; Tristán, J. Validation and Factorial Invariance of the Life Skills Ability Scale in Mexican Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052765

Vergara-Torres AP, Ortiz-Rodríguez V, Reyes-Hernández O, López-Walle JM, Morquecho-Sánchez R, Tristán J. Validation and Factorial Invariance of the Life Skills Ability Scale in Mexican Higher Education Students. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052765

Chicago/Turabian StyleVergara-Torres, Argenis P., Verónica Ortiz-Rodríguez, Orlando Reyes-Hernández, Jeanette M. López-Walle, Raquel Morquecho-Sánchez, and José Tristán. 2022. "Validation and Factorial Invariance of the Life Skills Ability Scale in Mexican Higher Education Students" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052765

APA StyleVergara-Torres, A. P., Ortiz-Rodríguez, V., Reyes-Hernández, O., López-Walle, J. M., Morquecho-Sánchez, R., & Tristán, J. (2022). Validation and Factorial Invariance of the Life Skills Ability Scale in Mexican Higher Education Students. Sustainability, 14(5), 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052765