Abstract

The purpose of this study was to widen the knowledge about the recycling behaviour of consumers in order to understand their motivations related to the separate collection of household waste. This work encompasses a segmentation analysis revealing discrepancies between the respondents, who were profiled into three clusters: Engaged in green, characterised by high values of pro-environmental attitudes; Indolent adopters, described by respondents revealing moderate attitudes towards sorting waste; and Ecological objectors, who do not appreciate the benefits of recycling. The results showed that regardless of the cluster type, the level of actual knowledge about segregation rules was similar and insufficient, which hinders the correct sorting of household waste. It was also found that special attention should be paid to the quality of the information provided by FMCG packaging. Our study highlighted the need for a mandatory, precise, and coherent system of packaging labelling in order to promote pro-environmental attitudes and enhance the effectiveness of recycling.

1. Introduction

Global pollution has become one of the most important environmental issues. This problem affects not only emerging economies, where it is the most visible due to the lack of effective waste collection systems, but it is also an urgent issue in developed countries. According to World Bank data, food and green waste, as well as paper and plastics, represent major waste streams. Since the latter ones are valuable secondary resources, recycling should be a preferred treatment operation applied for waste management [1]. In the European Union (EU-28) during the period of 2004–2018, the quantity of waste recycled increased from 45.9% (870 million tonnes) in 2004 to 54.6% (1184 million tonnes) in 2018, while the quantity of waste subjected to disposal decreased from 54.1% (1027 million tonnes) to 45.4% (984 million tonnes), respectively. In 2018, 37.9% of the total treated waste was recycled, 10.7% was backfilled, and 6.0% was treated using energy recovery. Among the remaining 45.4% of the total quantity, 38.4% was landfilled, 0.7% incinerated without energy recovery and 6.3% disposed of otherwise [2]. According to Eurostat data [2], there are significant differences among the EU Member States regarding various treatment methods. In 2019, the highest values of recycling rates of municipal waste were denoted for Germany (66.7%), Slovenia (59.2%), Austria (58.2%), the Netherlands (56.9%), Belgium (54.7%), Denmark (51.5%), and Italy (51.3%), while in the remaining countries the values were below 50% [3]. However, taking into account the increasing amount of municipal waste generated in the European Union (EU), recycling rates are still not sufficient. Therefore, waste management is one of the key elements of the European Union’s environmental policy, the EU’s legal framework, and a crucial part of an action plan regarding the transition to a circular economy. As a result, the amended Waste Framework Directive introduces ambitious targets for re-use and recycling rates defining the amounts which shall be increased to a minimum of 55%, 60%, and 65% by weight by 2025, 2030, and 2035, respectively [4]. A recommended way for the Member States to reach these undoubtedly challenging sustainability goals is the development of implantation plans (roadmaps) on a national level. In Poland, an appropriate document prepared by the Interdepartmental Circular Economy Group was approved by the Council of Ministers in September 2019 [5]. The Polish Roadmap focuses on several key areas such as sustainable industrial production and sustainable consumption, secondary raw materials and waste management, as well as innovation and investments. It also reflects recent changes in Polish rules of law since the implementation of the Waste Framework Directive induced several legislative amendments and had a considerable impact on the waste management system in Poland. Current regulations in this area are based on the European waste management hierarchy, strictly coherent with the circular economy model. Within the established five-step “waste hierarchy”, prevention is the most preferred method, followed by preparing for re-use, recycling, and recovery, while disposal should be the last option [4]. The Polish waste collection and management system has been established stepwise since 2016 [6]. In order to comply with European Union regulations, it is based on five fractions with assigned colours: blue (paper), yellow (plastic and metal), green (glass), brown (biowaste), black (mixed waste). Since September 2019, selective waste collection in Poland is mandatory. However, despite the obligation to handle waste in a particular way, the recycling rates are still insufficient in comparison with other European countries [7,8]. In 2020, in the EU, 505 kg of municipal waste were generated per capita and 48% was recycled (including composting), while in Poland the corresponding values were 346 kg and 39%, respectively [9,10]. Furthermore, with the adoption of the actual recycling targets for the EU, this issue is even more crucial. According to the decree of the Minister for the Climate and Environment of 19 December 2021 on the annual recycling rates of packaging waste [11], the values of 30% for plastic, 51% for aluminium, 55% for ferrous metals, 66% for paper and cardboard, 62% for glass, and 19% for wood are expected to be achieved in 2022. Other increased recycling targets set for 2029, are: 54%, 59%, 78%, 83%, 74%, and 29%, respectively, to the above-mentioned fractions. Selective collection is still a challenging task for Polish consumers, although the situation is slowly changing. In 2019, only 55% of Poles declared that they segregate waste into five fractions, while in 2020 this amount increased to 77% [12,13]. Nevertheless, their actual knowledge about selective waste collection rules is on an unsatisfactory level. According to the data gathered by ARC Rynek i Opinie, only 15% of the respondents answered correctly on three questions related to the disposal of paper tissue, the wrapping for a cube of butter, and a carton package for juice [14]. One of the reasons is the lack of environmental awareness and knowledge about waste management rules combined with inaccurate information placed on the packaging, which does not refer directly to a particular fraction. Recent studies related to these issues, however few, also indicate the importance of other socio-economic aspects determining the engagement of Poles in a separate collection of waste [12,13,14,15,16]. Among them, the recycling behaviour of Polish consumers and their attitudes to eco-labelling in relation to waste management are of importance, pointing out a crucial role of packaging as a sustainable communication tool [17].

Packaging, from the legal regulation’s perspective [18,19,20,21,22] and the functions performed [23,24,25], is a carrier of a lot of information, signs, and symbols. Displayed altogether, they might be counterproductive. The provided information is not only related to the need to ensure product and consumer safety but also necessary from the marketing point of view. It also has a direct impact on the multi-sensory customer experience at different stages of interaction with the packaging [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Communication through packaging helps build brand awareness and distinguishes the company from its competitors [28].

Packaging can be considered in its physical dimension, focusing mainly on material and constructional issues, but also in its functional dimension, which consists of elements determining its purchase-consumption nature. Purchase packaging affects the consumer at the time of buying, while consumption packaging has a greater impact at the time of use [33,34]. Packaging as an information carrier is the starting point for the further analysis of the presented research.

Various research points out that consumers, unfortunately, do not receive appropriate and understandable information, which results in confusion or indifference [35,36,37]. The informative function of packaging refers to the provision and uninterrupted transmission of relevant data to all participants, both in logistics chains and to individual consumers. In addition to the traditional descriptive form, information can be conveyed by pictograms, signs, and graphic symbols, which theoretically accelerate the identification of content and facilitate the understanding of the message. Data presented in graphic form (drawing, photograph, sign, pictogram) are often universal and accessible regardless of the language level of the recipient. It should be noted that the information value of packaging, determined by the obligatory code and the optional code, is an important component of its communication value. The correct choice of signs and codes forming the visual layer of packaging affects the correct perception of the product and, consequently, purchasing decisions. An excess of information or its inappropriate placement on packaging may cause information noise and the wrong perception of product features [38,39,40].

The information value of packaging plays also a crucial role in shaping the recycling behaviour of consumers, therefore proactive efforts are globally being made by researchers to improve the knowledge in this area [41,42,43,44,45]. The results of several works highlight the potential of packaging as an initiator of waste-sorting activity and indicate its impact on recycling effectiveness. However, it should be noted that the national perspective differs due to the various policies, segregation rules, and waste management systems existing in analysed countries. Nevertheless, good practices and success stories may be shared between other regions and provide the basis for a broad discussion in order to support the environmental attitudes and activities of consumers.

The aim of this study is to widen the knowledge about the recycling behaviour of consumers in order to understand the motivation of Poles related to the separate collection of waste. This paper encompasses segmentation studies based on attitudes towards recycling. It gives an insight into the environmental awareness and actual knowledge of Polish consumers related to selective waste management according to the legal requirements in Poland. Finally, it is also an attempt to provide information about factors important for consumers, which can stimulate the effective separation of waste with a particular emphasis on the information-related function of FMCG packaging.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

The study was conducted using a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) in January and February 2021 on a representative sample of adult Poles (N = 1029) in terms of gender, age, and education, according to Social Diagnosis reflecting the population of Polish consumers being active internet users. The study was carried out using the Market and Opinion Research Agency “SW Research” panel of respondents. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants involved in the survey are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

2.2. Questionnaire

The study was based on a specially designed questionnaire which consisted of six parts. The first part included 8 statements concerning consumers’ attitudes towards recycling scored on a 5-point Likert scale enabling respondents to specify their level of agreement: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree. The second part contained 4 statements describing the respondents’ experiences and attitudes regarding the selective collection. The third part included a set of 7 statements regarding the practical information about the selective collection of household waste which was scored on a 5-point Likert scale in order to verify the importance of examined factors from consumers’ perspective. The fourth part explored the level of awareness of the respondents regarding the selective collection of household waste. In this part, the actual knowledge was verified using a set of statements describing the separative waste management rules in relation to the six popular types of waste. The respondents could choose the answer between true or false. The fifth part investigated the potential of packaging innovations regarding extended information about the product and packaging’s characteristics. The last part included questions regarding the socio-demographic data of the respondents, such as gender, age, education level, and place of residence.

2.3. Cluster Analysis—Understanding Consumer Recycling Behaviour

A cluster analysis was applied to segment Polish consumers according to their attitudes towards selective waste sorting. Segmentation study allows us to classify respondents in groups and to show the similarities and differences between them in relation to attitudinal variables. The cluster analysis was used to give an insight into the motivations of respondents regarding their environmental awareness, values, and social norms as well as their level of knowledge. It may be noted that several studies were published concerning the environmental awareness and recycling behaviour of Poles [12,13,14,15,16,46,47]; however, only limited data were available regarding the profiling of Polish consumers [15]. The results showed important discrepancies between respondents indicating the need for tailored communication and marketing activities that should be undertaken in order to promote pro-environmental attitudes. The reported data also revealed a large information gap concerning selective waste management and its negative impact on the effectiveness of recycling. Therefore, the present study is aimed at the identification of the segments of Polish consumers in terms of their recycling behaviour in order to widen the knowledge about factors that may stimulate and promote selective waste collection. The role of packaging as a communication tool providing extended information was also explored.

In the scientific literature, two main approaches are applied in a cluster analysis [41]. One is based on socio-demographic criteria and another on psychographic and behavioural criteria. The theory of reasoned action (TRA) [48] and the theory of planned behaviour (TBP) [49], revealing the relationship between attitudes and behaviours, were successfully implemented for investigations regarding recycling, consumers’ choices concerning sustainable packaging, and green consumer behaviour [50]. The TBP is a conceptual extension of the theory of reasoned action (TRA) [51], which regards a consumer’s behaviour as influenced by behavioural intention. TBP assumes a rational basis for consumers’ behaviour, which is influenced by three variables: attitude towards the behaviour [51], subjective norms (the perception of the pressure of others’ opinions), and perceived behavioural control (the person’s perception of their own ability to perform a behaviour) [50,52]. An interesting approach regarding the understanding of consumer recycling behaviour was proposed by Park and Ha [53]. They showed that recycling intention is determined both by attitudes toward recycling and by perceived behavioural control from TPB, as well as by personal norms from the norm action model (NAM, Shwartz 1997 [54]). They suggested that subjective norms indirectly influence recycling intention, having an impact through attitude, personal norms, and perceived behavioural control [53]. According to NAM, personal norms refer to the individual’s self-expectations for a specific behaviour [53], which originate from a moral obligation to perform a behaviour [55]. Previous scientific studies have shown that personal norms directly affect environmental behaviour [55,56,57].

In this work, the above-mentioned relations were taken under consideration in order to study the recycling behaviour of Polish consumers. Assuming the importance of the range of information provided on FMCG packaging for effective recycling, selected guidelines covering this issue were also used as the segmentation base.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical data analysis was conducted using 3 kinds of tests:

- −

- A clustering of respondents based on normalised answers from questions included in the first and the third part of the questionnaire (K-means method were chosen and performed—3 clusters were chosen);

- −

- Chi-square tests comparing cluster alignments and other answers (socio-demographic data and questions about knowledge and attitudes towards innovative packaging solutions);

- −

- An ANOVA with posthoc tests was conducted to determine the significance of the differences between clusters in the area of actual and declared knowledge about segregation.

A cluster analysis was conducted in order to segment respondents into groups based on similarities (in the case of the same cluster) and on differences (in the case of belonging to different clusters). Two questions from the questionnaire (15 variables), included in the first and third part of the questionnaire, were taken into consideration. Other questions were used for comparison purposes. All questions were standardised (the Z-score was used) in order to avoid errors. Cronbach’s alpha test for the internal consistency of diagnostic tools (questionnaire) was also performed.

3. Results

Cluster Analysis Results

The high value of Cronbach’s alpha determined for analysed questions indicated an internal consistency of the questionnaire (0.844). Three clusters were identified due to the consistency of groups and the abundance of members of each group. The final centres of the clusters were shown in Table 2. The mean refers to the standardised value (positive values indicate being above average, negative values indicates being below the average of the question). Table 3 shows a description of the clusters with respect to the demographic attributes.

Table 2.

Results of cluster analysis.

Table 3.

Description of the clusters with respect to the demographic attributes.

Cluster 1: Engaged in green is characterised by high values of pro-environmental attitudes as well as components related to the respondents’ ability to sort waste separately. It comprises of people who express an inner conviction that sorting waste is beneficial for the environment and for society. They are strongly influenced by social values and personal norms.

Cluster 2: Ecological objectors is represented by respondents who do not appreciate the benefits of sorting waste to protect the environment and society. They are extremely indifferent to social and personal norms and find sorting waste difficult.

Cluster 3: Indolent adopters is described by respondents revealing moderate attitudes towards sorting waste. It is also characterised by an average impact of social and personal norms. Cluster 3 covers respondents who perceived difficulty regarding selective sorting of waste on a medium level.

An analysis of the composition of the clusters with respect to socio-demographical attitudes has shown some differences between them (Table 3). Cluster 1 (Engaged in green), the second-largest group in the study (N = 411), constituted 39.94% of the surveyed population. This cluster is dominated by women (60.8%, Chi-square 27.56, p-value 0.000), which indicates their strong involvement in environmental issues. Cluster 1 is mainly represented by people between 21 and 40 years of age, with secondary or higher education, who live in cities. Interestingly, this cluster is also characterised by a significant group of people above 51 years of age (Chi-square 19.35, p-value 0.036), which implies that respondents of this age are engaged in the selective collection of waste. Cluster 2 (Ecological objectors) constitutes 11.95% of the studied population. Although this is the smallest group, it is worth observing and analysing in order to recognise the causes for a negative attitude towards waste segregation. This group is dominated by men aged up to 40, with secondary or higher education, living in large cities. Cluster 3 (Indolent adopters) is the most numerous group (48.11%, N = 495) among all distinguished. Without a clear gender representation, Cluster 3 is characterised mostly by young people aged 21 to 40, and city dwellers with secondary or higher education. Since it constitutes such a large group of respondents, the lack of conviction may result in the strengthening of attitudes visible in Cluster 2 (Ecological objectors), which, as a consequence, would be decisive for the further efficiency of selective waste sorting. Therefore, intensive information activities and educational campaigns to motivate consumers to adopt pro-ecological habits are of importance. It was also observed that neither the place of residence nor the level of education were significant from the cluster analysis point of view.

The purpose of this study was also to examine the level of actual knowledge of respondents regarding selective waste sorting rules since separate collection is mandatory in Poland, and certain efforts to promote recycling, as well to provide particular guidelines, have already been undertaken at regional and national levels. In order to determine the level of knowledge, respondents were asked to indicate whether the six statements, concerning the separate collection rules of six popular types of household waste, were correct (true) or incorrect (false). Interestingly, the results showed that regardless of the cluster type, the level of actual knowledge of respondents was similar, since the differences between them were statistically insignificant (Table 4 and Table 5). As can be seen from Table 4, slightly more than three correct answers (from six questions) were chosen, while the best results were denoted for cluster 1 (Engaged in green) and the worst for cluster 2 (Ecological objectors), however statistically insignificant.

Table 4.

Description of clusters in terms of the level of knowledge regarding selective waste sorting.

Table 5.

Results of one-way ANOVA—the level of knowledge regarding selective waste sorting.

In the case of the rest of the questions, the results were statistically significant, and posthoc tests (the Tukey test) revealed that all clusters differed. Considering the answers in detail, it can be observed from Table 6 that within Cluster 1 (Engaged in green), the worst results were denoted in the case of question 2 (about receipts), since only 28% of the answers were correct. The analysed clusters do not differ significantly in the case of questions 2 (about receipts), 4 (about bottles for edible/engine oil), 5 (about glass containers for drugs), and 6 (about light bulbs). In the case of questions 1 and 3, Cluster 1 (Engaged in green) answered in the best way, while Cluster 2 (Ecological objectors) answered the worst.

Table 6.

Description of clusters with respect to practical knowledge about recycling rules.

For further consideration, the questions analysed in the ANOVA analysis were also taken into a cross-table analysis in order to show the distribution of results. Chi-square tests were additionally calculated (Table 7).

Table 7.

Description of clusters in terms of experience with selective waste collection.

The results presented in Table 7 show that there are statistically significant differences (Chi-square = 199.1, p-value < 0.001) between experiences with sorting waste among the analysed clusters. Respondents concentrated in Cluster 1 (Engaged in green) declared the most frequently that selective waste sorting is easy for them. On the contrary, Cluster 2 (Ecological objectors) is characterised by the highest number of respondents who do not segregate waste. They also declared more often that sorting waste is difficult. Interestingly, it was observed that 1.6% of the total number of respondents declared that they do not segregate waste, although the selective collection of waste is mandatory in Poland.

Moreover, the results revealed statistically significant differences between clusters (Chi-square = 271.9, p-value < 0.001) regarding the potential of interactive packaging. Cluster 1 (Engaged in green) covers respondents who declared more frequently that interactive packages can serve as a sustainable communication tool providing information useful for efficient waste sorting (Table 8). Cluster 3 (Indolent adopters) represents a group of respondents with a moderate attitude towards the segregation of waste and the opinion that extended information on packages, regarding sorting waste, can be useful and helpful. In most cases, the obtained values are a little bit below the average, which means that they assessed the potential of additional information as less important. Cluster 2 (Ecological objectors) comprises a group of consumers with negative attitudes towards sorting waste. They also assessed the usefulness of additional information provided on packaging regarding the sorting of waste lower than respondents representing other clusters.

Table 8.

Description of clusters regarding the potential of interactive packaging as a tool useful for efficient waste sorting.

It was also observed that there are statistically significant differences between clusters (Chi-square = 246.3, p-value < 0.001) regarding opinions about innovative packaging solutions, such as interactive packages with “extended labels”, which are delivering information about the way the product can be prepared for consumption, about allergens, food origins, etc. (Table 9). The results showed that Cluster 3 declared more frequently that interactive packaging could be useful as an attractive and valuable communication tool.

Table 9.

Description of clusters regarding the potential of interactive packaging as a tool for extended information about the product characteristics.

4. Discussion

A cluster analysis of the obtained results revealed three segments representing different attitudes towards selective waste collection: Engaged in green, Indolent adopters, and Ecological objectors. Engaged in green (48.11% of the total number of respondents) is characterised by consumers highly involved in effective waste sorting. Respondents in this cluster are strongly convinced that sorting waste is beneficial to the environment and society and find it easy. They are influenced by the pressure of social and personal norms. Engaged in green are also the most interested in precise information on how to handle packaging prior to discharging to make recycling more effective. Cluster 2: Ecological objectors (11.95%) encompasses respondents who do not consider sorting waste as an activity beneficial for the environment or society, nor as a habit. They are poorly influenced by social and personal norms and find selective waste collection difficult. Indolent adopters (39.94%) comprises respondents who perceive the sorting of household waste as moderately beneficial for the environment and society and find it cumbersome. They are rather indifferent to social and personal norms. In light of the above, it can be stated that there is still a need for more intensive information activities and educational campaigns in order to motivate consumers to adopt pro-ecological habits. Moreover, the precise and direct information provided by packaging may promote and facilitate selective waste sorting and enhance the effectiveness of recycling. The discussed results showed some similarities with other studies undertaken by the Market and Opinion Research Agency SW Research in March, June, and October 2020 [15], although different criteria and bases for segmentation were applied. According to the data presented in the above-mentioned report, five profiles of respondents were distinguished: Eco-attentive (35% of the analysed population), Eco-enthusiast (29%), Eco-confused (11%), Sceptical about green marketing (13%), and Eco for show (12%). The most numerous groups are composed of respondents with good environmental awareness (Eco-attentive and Eco-enthusiast), who undertake several pro-ecological activities such as saving electricity or water and sorting waste; however, their actual knowledge of segregation rules was not assessed. Eco-confused do not demonstrate negative attitudes towards pro-ecological activities, but they are passive. Together, respondents described as Sceptical about green marketing and Eco for show constitute a group of people who should be encouraged to get involved and who need the motivation to take part in pro-ecological activities.

The cluster analysis results showed that within Engaged in green, women were the most involved in effective waste sorting. This is coherent with the data provided by the ProKarton Foundation (Poland), which were collected in September 2021, revealing that women segregated waste more often than men [13].

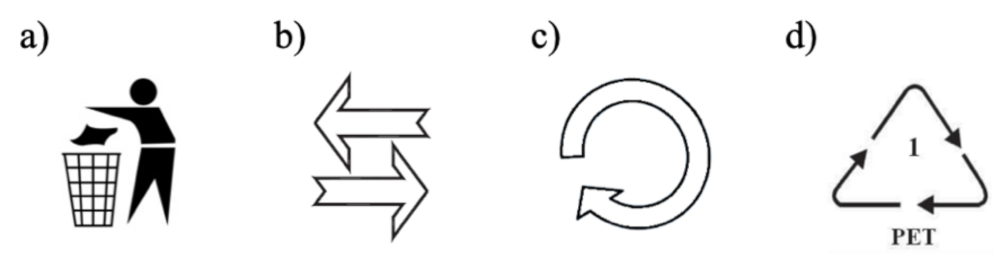

The results of our study also showed that regardless of the cluster type, the level of actual knowledge of respondents about waste sorting rules was similar and insufficient. It implies that notwithstanding the environmental awareness and degree of involvement of respondents in recycling, there is an information gap that hinders the correct sorting of household waste. Our results reflect the current legal situation in Poland, where there is no obligatory labelling of packaging in terms of the type of material or handling hints regarding selective waste sorting. Although there are guidelines for municipalities and residents referring to the selective collection of various types of household waste, laid down by the Ministry of Climate and Environment [58], their application in practice by consumers remains difficult. There are also some discrepancies in separate collection rules among particular regions in Poland, which may contribute to information noise. Our results showed that, similarly, facultative eco-labelling still remains problematic [59]. The most popular examples of eco-labelling used in product packaging are presented below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chosen types of eco-labelling: (a) dispose of according to the local regulations, (b) reusable packaging, (c) packaging suitable for recycling, (d) packaging material type: 1—poly(ethylene terephthalate). Source: (a) ČSN 77 0053 Packaging—Packaging waste—Instructions and information on manipulation with used packaging, Obaly—Odpady z obalů—Pokyny a informace pro nakládání s použitým obalem [60]; (b–d) Ordinance of Minister of Environment on the templates of packaging labelling of 3 September 2014 [61].

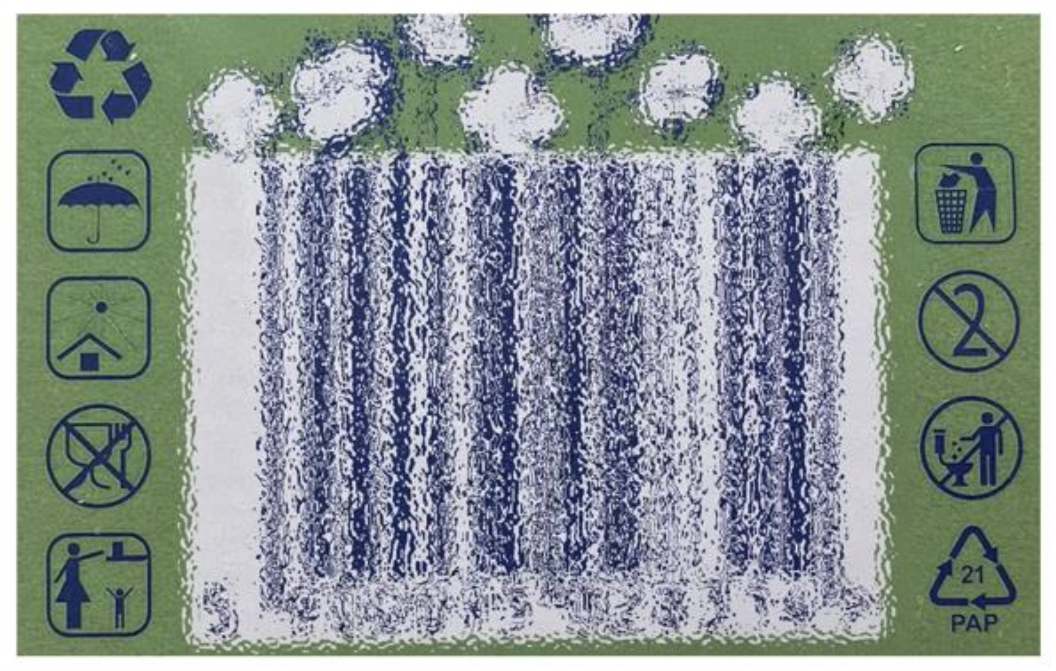

It was observed that consumers are often not familiar with their meaning. Moreover, none of them serve as a direct guideline referring to a particular type of waste fraction. Eco-labels are often combined with a set of other symbols concerning the product’s characteristics or handling rules, applied within the entire logistic chain (Figure 2). However, it must be underlined that excessive labelling or improper application is not communicative but, rather, confusing. Misleading consumers and greenwashing are legally prohibited.

Figure 2.

An example of a purchase packaging that conveys information concerning the product’s characteristics and handling rules.

It is worth noting that these issues are considered highly important at the community level, while the packaging industry and consumer product manufacturers endorse the need for relevant and consistent information on how to segregate household waste correctly in order to support circular economy initiatives [62]. Simultaneously, in the Polish market, there are initiatives undertaken by several retailers regarding the labelling of packaging with a particular fraction of waste [63]. However, the proposed systems are not coherent due to the different symbols used to indicate selective waste sorting rules or to provide detailed information about particular packaging elements when the packaging is composed of varied materials.

In light of the above, the information should be precise, detailed and reliable. In some cases, two-dimensional labelling may be enhanced with interactive packaging solutions in order to provide additional assistance. Digital packaging offering virtual content, provided by QR codes, augmented reality, or invisible watermark coding, enables customised features, content, and style and opens a new way of communication with consumers. It may also provide professional information which is not available on a traditional label. Therefore, the interest in such a tool was taken into consideration. The results showed that 87.4% of respondents representing Engaged in green and 68.7% from Indolent adopters declared that extended information provided by interactive packaging would be useful (33.6% and 50.9%, respectively) and very useful (53.8% and 17.8%, respectively) in household waste sorting. The survey results are a part of the project “Interactive packaging as a new communication tool on B2C market” conducted from 1 September 2020 to 28 February 2022, devoted to the exploration of consumers’ experience with interactive solutions using qualitative and quantitative research methods.

5. Conclusions

The results showed that consumers’ recycling behaviour is influenced by personal norms and behavioural intentions as well as their actual knowledge. A segmentation analysis revealed important discrepancies between respondents, who were profiled into three clusters: Engaged in green, characterised by high values of pro-environmental attitudes; Indolent adopters, described by respondents revealing moderate attitudes towards sorting waste; and Ecological objectors, who do not appreciate benefits of sorting waste. Therefore, tailored communication and marketing activities regarding different types of consumers should be proposed to promote pro-environmental attitudes. Regardless of the cluster type, the level of the actual knowledge of the respondents about waste sorting rules was similar and insufficient. It implies that notwithstanding the environmental awareness and degree of involvement of respondents in recycling, there is an information gap that hinders the correct sorting of household waste. Assessing the role of packaging as a tool affecting separate waste collection, special attention should be paid to the information it provides since a majority of respondents (Engaged in green and Indolent adopters) declared that more precise guidelines are needed in order to facilitate the sorting of waste, which in fact determines the effectiveness of recycling. Our study highlighted the need for a mandatory, precise, and coherent system of packaging labelling in order to provide consumers with explicit and comprehensible recycling guidelines. Confused consumers, even those involved in pro-ecological activities, turn their doubts into recycling mistakes.

6. Research Limitations

The limitations of this study include the fact that the survey was conducted using the CAWI method, including internet users only, which do not fully cover the country’s population. However, the survey encompassed a representative sample in terms of gender, age, and education according to data from the Polish Central Statistical Office and the SW Research Market and Opinion Research Agency’s panel of respondents. Secondly, the cluster analysis reflects the attitudes of respondents among the Polish population, considering actual legal requirements in Poland. Therefore, although selective waste management is one of the key elements of the EU environmental policy, national perspectives may differ within the other Member States, while recommendations regarding post-consumer waste collection and segregation systems are not homogeneous. Nevertheless, the authors assume that the obtained results may be useful not only from a national perspective but also contribute to a wider discussion regarding the informative value of packaging on the European market and its potential in supporting the environmental attitudes and activities of consumers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: P.W. and K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project financed within the Regional Initiative for Excellence programme of the Minister of Science and Higher Education of Poland, years 2019–2022, grant no. 004/RID/2018/19, financing 3,000,000 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Minister of Science and Higher Education of Poland (“The project financed within the Regional Initiative for Excellence programme of the Minister of Science and Higher Education of Poland, years 2019–2022, grant no. 004/RID/2018/19, financing 3,000,000 PLN”).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The World Bank. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Waste Statistics. Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics#Waste_treatment (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1219551/municipal-waste-recycling-eu-by-country/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste, L 150/109. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L0851&from=EN (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Polish Roadmap towards the Transition to Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj/gospodarka-o-obiegu-zamknietym (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Decree of the Minister for the Environment of 29 December 2016 on the Detailed Method of Separate Collection of Chosen Waste Fractions (Dz.U.2019.2028). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20170000019/O/D20170019.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Smol, M.; Duda, J.; Czaplicka-Kotas, A.; Szołdrowska, D. Transformation towards Circular Economy (CE) in Municipal Waste Management System: Model Solutions for Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, P.; Chawla, Y. Circular Economy in Poland: Profitability Analysis for Two Methods of Waste Processing in Small Municipalities. Energies 2020, 13, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Municipal Waste Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Municipal_waste_statistics (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Eurostat. Recycling Rate of Municipal Waste. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_wm011/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Decree of the Minister for the Climate and Environment of 19 December 2021 on the Annual Recycling Rates of Packaging Waste for Particular Years up to 2030. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20210002375/O/D20212375.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- ProKarton Report 2020, Jak Zmienia się Wiedza Polaków na Temat Segregacji Zużytych Kartonów do Płynnej Żywnosci? (How is Knowledge of Poles About Carton Packages Selective Collection Changing?). Available online: https://prokarton.org/77-polakow-segreguje-odpady-opakowaniowe-to-az-o-19-punktow-procentowych-wiecej-niz-w-2019-wiecej-osob-wie-takze-jak-prawidlowo-segregowac-kartony-po-mleku-i-sokach/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- ProKarton Report 2021, Jak Zmienia się Wiedza Polaków na Temat Segregacji Zużytych Kartonów do Płynnej Żywnosci? (How is Knowledge of Poles About Carton Packages Selective Collection Changing?). Available online: https://prokarton.org/77-polakow-segreguje-odpady-opakowaniowe-tegoroczne-wyniki-cyklicznego-badania-spolecznego-fundacji-prokarton/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- ARC Rynek i Opinia Report, September 2019, Konsumenci a Gospodarka Obiegu Zamkniętego (Consumers and the Circular Economy). Available online: https://arc.com.pl/konsumenci-lepiej-oceniaja-firmy-zaangazowane-spolecznie/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- EKObarometr Report SW Research and Ecowipes, Na Drodze do Zielonego Społeczeństwa (The Road towards Green Society). Available online: https://swresearch.pl/raporty/na-drodze-do-zielonego-spoleczenstwa-jak-polacy-podchodza-do-ekologii (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Raport Banku Ochrony Środowiska 2020, Warszawa Październik 2020. Available online: https://www.bosbank.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/30891/Barometr-ekologiczny-Polakow.-Co-robimy,-aby-chronic-srodowisko.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Cichocka, I.; Krupa, J.; Mantaj, A. The consumer awareness and behaviour towards food packaging in Poland. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC of 20 December 1994 on Packaging and Packaging Waste. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31994L0062&from=EN (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011R1169&from=EN (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on Cosmetic Products. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1223/2021-10-01 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Regulation (EC) No 648/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 on Detergents. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/648/oj (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Piergiovanni, L.; Limbo, S. Introduction to Food Packaging Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ampuero, O.; Vila, N. Consumer perceptions of product packaging. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emblem, A.; Emblem, H. (Eds.) Packaging Technology. Fundamentals, Materials, and Processes; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Sawston, UK, 2012; pp. 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- De Pilli, T.; Baiano, A.; Lopriore, G.; Russo, C.; Cappelletti, G.M. Sustainable Innovations in Food Packaging; SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Crié, D. Communicating packaging eco-friendliness: An exploration of consumers’ perceptions of eco-designed packaging. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; da Silva, R.V.; Davcik, N.S.; Faria, R.T. The role of brand equity in a new rebranding strategy of a private label brand. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, C.; Spence, C. (Eds.) Multisensory Packaging. Designing New Product Experiences; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds, G.; Woods, A.T.; Spence, C. ‘Show me the goods’: Assessing the effectiveness of transparent packaging vs. product imagery on product evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Noseworthy, T.J. Place the logo high or low? Using conceptual metaphors of power in packaging design. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompay, T.J.L.; Finger, F.; Saakes, D.; Fenko, A. See me, feel me: Effects of 3D printed surface patterns on beverage evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, L.; Krishna, A.; Schwarz, N. Positioning rationality and emotion: Rationality is up and emotion is down. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 632–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krishna, A.; Cian, L.; Aydınoğlu, N.Z. Sensory Aspects of Package Design. J. Retail. 2017, 93, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankiel, M.; Wojciechowska, P.; Wiszumirska, K. Packaging Innovations for Consumer Goods; University of Economics and Business: Poznań, Poland, 2021. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir Kavei, F.; Savoldi, L. Recycling Behaviour of Italian Citizens in Connection with the Clarity of On-Pack Labels. A Bottom-Up Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, K.; Dahlén, L. Source Separation of Household Waste Materials. In Resource Recovery to Approach Zero Municipal Waste; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ecoplus, BOKU, Denkstatt, OFI. Food Packaging Sustainability: A Guide for Packaging Manufacturers, Food Processors, Retailers, Political Institutions & NGOs. Based on the Results of the Research Project “STOP Waste—SAVE Food”. Vienna, February 2020. Available online: https://www.teraz-srodowisko.pl/media/pdf/aktualnosci/11141-guideline-stopwaste.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Tijus, C.; Barcenilla, J.; de Lavalette, B.C.; Meunier, J. Chapter 2: The Design, Understanding and Usage of Pictograms. In Written Documents in the Workplace; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forceville, C. Visual and Multimodal Communication: Applying the Relevance Principle; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Can I Recycle This? A Global Mapping and Assessment of Standards, Labels and Claims on Plastic Packaging. 2020. Available online: https://www.consumersinternational.org/media/352255/canirecyclethis-finalreport.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Vasieleva, E.; Ivanova, D. Towards a sustainable consumer model: The case study of Bulgarian recyclers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemat, B.; Razzaghi, M.; Bolton, K.; Rousta, K. The Role of Food Packaging Design in Consumer Recycling Behavior—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taufik, D.; Reinders, M.J.; Molenveld, K.; Onwezen, M.C. The paradox between the environmental appeal of bio-based plastic packaging for consumers and their disposal behaviour. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 705, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; McDonald, S.; Korobilis-Magas, E.; Osobajo, O.A.; Awuzie, B.O. Reframing Recycling Behaviour through Consumers’ Perceptions: An Exploratory Investigation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Long, R.; Li, Q. Impact of Information Intervention on the Recycling Behavior of Individuals with Different Value Orientations—An Experimental Study on Express Delivery Packaging Waste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blue Media Report 2020. Available online: https://bluemedia.pl/eco (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Green Generation, Styczeń 2020, Mobile Institute. Available online: https://mobileinstitute.eu/green (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, G.; Pires, A.; Portela, G.; Fonseca, M. Factors affecting consumers’ choices concerning sustainable packaging during product purchase and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 103, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. Consumer values, the theory of planned behaviour and online grocery shopping. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yoo, J.H.; Zhou, H. To read or not to read: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour to food label use. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding Consumer Recycling Behavior: Combining the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influence on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, G.; Bai, Y. Voluntary or Forced: Different Effects of Personal and Social Norms on Urban Residents’ Environmental Protection Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, H.K.; Yoo-Kyoung, S. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Our Waste” Program of Ministry of Climate and Environment. Available online: https://naszesmieci.mos.gov.pl (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Wojciechowska, P.; Wiszumirska, K. Consumer attitudes towards digital packaging as a novel communication tool on B2C market. In International Conference on Finance and Economic Policy, Proceedings of International Conference on Finance and Economic Policy (ICOFEP) 5th Edition: New Economy in the Post-Pandemic Period, Poland, 21–22 October 2021; Warchlewska, A., Ed.; Poznań University of Economics and Business: Poznań, Poland, 2021; p. 78. ISBN 978-83-959704-1-2. [Google Scholar]

- ČSN 77 0053 Packaging—Packaging Waste—Instructions and Information on Manipulation with Used Packaging (Obaly—Odpady z obalů—Pokyny a informace pro nakládání s použitým obalem). Available online: https://www.technicke-normy-csn.cz/csn-77-0053-770053-227003.html#. (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Ordinance of Minister of Environment on the Templates of Packaging Labelling of 3 September 2014. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20140001298/O/D20141298.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- EUROPEN. Available online: https://www.europen-packaging.eu/news/the-packaging-industry-and-consumer-product-manufacturers-calling-for-an-eu-approach-to-packaging-waste-labelling/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Coalition of Five Factions, Poland. Available online: https://5frakcji.pl/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).