Abstract

To both survive and develop continuously, enterprises must overcome many kinds of competition and challenges. Cultivating employees’ active and sustainable organizational citizenship behavior is important for enterprises to successfully cope with turbulence and uncertain events during their development. Building on social exchange theory, this study proposes a theoretical framework. In this framework, belief in a just world has a certain predictive effect on organizational citizenship behavior, and this effect is affected by interpersonal intelligence. In this study, we investigated the development level of and factors influencing employees’ organizational citizenship behavior in current organizations. This research adopted the empirical research method of a questionnaire survey, and investigated 230 employees from 15 different enterprises by using the Belief in a Just World Scale, Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale, and Interpersonal Intelligence Scale. After excluding the questionnaires that did not meet the requirements, a total of 193 valid questionnaires were obtained. To estimate the proposed relationships in the conceptual model, we analyzed the data through SPSS-21. The results showed that belief in a just world, interpersonal intelligence, and organizational citizenship behavior were significantly positively correlated. Interpersonal intelligence played a moderating role between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior; the belief in a just world of individuals with high interpersonal intelligence had a more significant positive predictive effect on organizational citizenship behavior. This meant that under a certain level of belief in a just world, a high level of interpersonal intelligence was more conducive to promoting employees’ sustainable organizational citizenship behavior.

1. Introduction

In the living environment of economic globalization and increasingly intensified market competition. Organizations need to be more flexible and innovative if they want to continue to grow, which require their employees to assume more responsibility beyond their duties, take more initiative, perform adaptive and innovative behaviors, and contribute wisdom and strength to the organization. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) has attracted increased attention from managers and researchers because it can improve organizational efficiency, help the organization to adapt to changing competitive market environments, and strengthen self-management and other emerging management methods.

Throughout previous studies, the research on the relationship between fairness and organizational citizenship behavior mainly focuses on the impact of organizational justice on organizational citizenship behavior [1,2]. Organizational justice has not only been considered one of the proximal determinants of OCBs [3,4], but also has sometimes been considered a proxy for social exchange [5]. Put directly, fair treatment of employees can cause them to redefine their employment in terms of social exchange, with OCB as a common exchangeable resource [3]. However, the organizational justice mentioned here specifically refers to distributive justice, procedural justice, and interactive justice, that is, employees’ perception of the fairness of the rules and regulations or policies implemented by the organization, such as compensation, benefits, promotion, training, rewards, and punishments, which are closely related to their own interests [6]. These senses of fairness can be created by organizations and are the focus of previous studies. However, the justice beliefs of employees themselves are the key to our discussion later. This belief affects the work and life of employees in different ways. For example, employees who believe that their efforts will be rewarded, no matter what rules and regulations the organization makes, will work diligently and make progress; while other employees with weak belief in justice, and facing the company’s harsh policies, feel that their future is bleak, they have no intention of working, and they are decadent and backward. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the impact of employees’ beliefs in a just world on organizational citizenship behavior to determine the implications for practitioners.

In addition, according to previous research, interpersonal intelligence has a significant impact on an individual’s positive behavior (helping behavior, prosocial behavior, etc.) [7,8]. Whether organizational citizenship behavior, a positive out-of-role behavior of employees, is also affected by interpersonal intelligence, has not yet been explored. Particularly interpersonal intelligence as an moderating role needs to be addressed and investigated by researchers. In enterprises, many employees do not know how to get along with colleagues and superiors. Due to the lack of communication, it not only affects their work efficiency, but also reduces their interest in the organization and work, thereby reducing their enthusiasm for positive behavior. Therefore, this study aims to reveal how interpersonal intelligence affects employees’ behavioral performance and its moderating role between beliefs in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior.

On the basis of the above-discussed literature, this study analyses the relationships between beliefs in a just world, organizational citizenship behavior, and interpersonal intelligence. Thus, on the basis of the above-discussed literature, the research questions (RQ) addressed are as follows:

- RQ1

- : How does belief in a just world affect organizational citizenship behavior?

- RQ2

- : How does interpersonal intelligence affect organizational citizenship behavior?

- RQ3

- : How does interpersonal intelligence moderate the relationship between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior?

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 is devoted to the conceptual background, frames the hypotheses, and outlines the theoretical framework. Section 3 addresses the methodology. Section 4 presents the results of the data analysis. Section 5 and Section 6 conclude the study and provide a discussion of the results and their implications. Section 7 elaborates on the limitations of the study and future research directions.

2. Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Belief in a Just World

The concept of Belief in a Just World was first put forward by the American psychologist, Lerner. His core content is that in this just world, people get what they deserve, and what they get is what they deserve. There are two dimensions of the belief in world justice, namely, the general belief in world justice and the individual belief in world justice. The general belief in world justice means that the world is just to others, and the individual belief in world justice means that the world is just to itself [9]. The belief in a just world as a common concept of fairness held by employees is a psychological demand, belief, and pursuit of justice for individuals; that is, individuals believe that they live in a just world, that the world is equitable and harmonious, and that they will receive what they deserve through continuous effort [9]. This belief in a just world can be regarded as a difference in characteristics between individuals [10]. As a basic model, the belief in a just world enables people to steadily face the external environment, and influences the processing, coding, and recalling of people’s daily experiences [11]. From the value level, it plays a pivotal role in individual adaptation to complex physical and social environments. As a kind of social cognitive tendency, people keep this belief. Even when faced with unfair or threatening events, they will reframe the belief of justice in a psychologically conditioned way, reduce anxiety and uneasiness, enhance the sense of control over the environment and hope for the future, and minimize unfair losses [12,13]. Thus, it can be seen that from the perspective of adaptation, people not only need to maintain the belief in justice, but also need to develop or enhance the belief in a just world, so as to make themselves more adaptable to the environment and social requirements. Furthermore, high interpersonal intelligence can help individuals to improve and gradually perfect such beliefs.

2.2. Interpersonal Intelligence and Belief in a Just World

Gardner thought that interpersonal intelligence is the ability to understand and create differences and respond effectively to various interpersonal cues, including social sensitivity, social insights, social communication, and altruistic behaviors [14]. Employees with high interpersonal intelligence can be leaders among their peers and encourage people to work together to create a sense of belonging; they typically have rich common sense, superb social skills, and the ability to make friends in various social groups; they are also more willing to work collectively and show high working efficiency [15]. Therefore, good interpersonal intelligence can effectively improve the interpersonal atmosphere of organizations or groups, help individuals to communicate and cooperate voluntarily, eliminate contradictions, enhance cohesion, and thus promote people’s belief in a just world. From the stage and sequence of individual psychological development, high interpersonal intelligence belongs to a higher level of psychological development. Compared with low interpersonal intelligence, people with high interpersonal intelligence can analyze things more comprehensively, objectively and rationally, deal with problems and gain insight into the future development state and correct direction of things. This high-level ability in interpersonal intelligence will strengthen and promote the development of the belief in a just world.

Therefore, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 1.

The association between the belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence is positive and significant. The higher the interpersonal intelligence, the higher the belief in a just world.

2.3. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Belief in a Just World

Organizational citizenship behaviors are important to the sustainable development of enterprises. The concept of OCB was formally proposed by Organ and Dennis [16]. Organizational citizenship behavior is the spontaneous behavior of employees rather than one defined by the normal work-performance-based salary system. However, such behavior can promote organizational work performance by maintaining and improving an organizational environment that is conducive to work performance. Different from work-specific in-role behaviors, organizational citizenship behavior is extra-role behavior that includes cooperating with others, volunteering to undertake additional tasks, helping others finish their work, volunteering to perform duties beyond the work requirements, and other behaviors [17]. Good organizational citizenship behavior features altruism (e.g., taking the initiative to help others handle tasks or issues related to the organization), a sense of responsibility (e.g., performing duties far beyond the work requirements), courtesy (e.g., giving advance notice, reminding, and consulting), a sportsperson-like spirit (e.g., avoiding complaints or grievances), and civic virtue (e.g., actively participating in the organization’s governance and providing appropriate feedback) [18,19,20]. All these behaviors serve as a prerequisite to continuously ensure the effective operation of an organization. Therefore, sustainable organizational citizenship behaviors are crucial for enterprises to gain competitive advantages. Some studies discovered that employees with positive emotions are more willing to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors [21,22]. Undoubtedly, a relatively high level of belief in a just world is a positive emotion status.

The belief in a just world means employees regard their world as fair and meaningful, which cultivates their positive outlook for the future and expectation of their life experience, hence effectively promoting employees’ positive behaviors [23]. Research has shown that an individual’s belief in a just world has a positive impact on altruistic, prosocial behaviors, and other helping behaviors. Zuckerman discovered a positive correlation between the belief in a just world and altruistic behaviors through experimental research [24]. The results demonstrated that individuals with a strong belief in a just world were more willing to offer assistance than those with a weak belief in a just world. Depalma et al. also found that individuals with a strong belief in a just world were more willing to help those groups that were treated unfairly and exhibited more helping behaviors [25]. Otto and Schmidt pointed out that employees with a strong belief in a just world displayed higher job satisfaction and organizational loyalty, and were more willing to demonstrate organizational citizenship behaviors [26]. Laurin et al. reported that for groups in unfavorable social situations, the stronger the belief in a just world, the more willing they were to devote their energy and time to long-term work and careers, and the more resilient they were in the face of difficulties [27].

Previous studies verified that employees’ views on organizational justice exert a strong impact on organizational citizenship behaviors [28,29] because perceived justice promotes trust in non-contractual communication between employees and organizations [30]. Moorman confirmed a positive correlation between the sense of fairness and organizational citizenship behaviors [31]. The results showed that compared to employees with a weak sense of fairness, those who have a strong sense of organizational fairness demonstrate a positive work attitude and perform extra-role behaviors to repay the organization after fulfilling their duties. In addition, Niehaff and Mooman stated that when employees feel that organizational care and distribution are unfair, their discontent will be balanced by reducing personal input, but they will not directly reduce work input to achieve a sense of balance in their mind since reducing such input can directly affect their job performance and remuneration [32]. Instead, organizational citizenship behaviors with hidden characteristics are used to reduce input, thus eliminating employees’ sense of unfairness. To summarize, some connections must exist between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behaviors, which deserves further exploration.

Therefore, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 2.

The association between the belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior is positive and significant.The higher the belief in a just world, the higher the organizational citizenship behavior.

2.4. Interpersonal Intelligence and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Belief in a just world is the motivation for individuals to pursue long-term goals and follow social norms. It has an important adaptive function because it enables people to better adapt to their material and social environment; to believe that the environment is stable, fair and organized [9]; and interpersonal intelligence related to responding to and understanding information, as well as establishing social contact and interaction with others [33]. High-level interpersonal intelligence can recognize other people’s emotions, motives, and desires, and enable appropriate responses. On the one hand, high-level interpersonal intelligence can further strengthen people’s belief in a just world; on the other hand, it plays an important role in the process of stimulating and implementing organizational citizenship behavior. For instance, Fitri studied the correlation between the interpersonal intelligence and prosocial behaviors of primary school students; they found a significant positive correlation between the two variables, and that children with high interpersonal intelligence were more inclined to show behaviors of helping others [7]. Cirelli clarified that high interpersonal intelligence promoted individuals’ prosocial behaviors and increased the frequency of prosocial behaviors [8]. These studies’ findings indicated that interpersonal intelligence is significantly related to positive behaviors and that by improving interpersonal intelligence, employees can get along with colleagues, superiors, and subordinates; cooperate better with others; and are more willing to perform some extra-role behaviors that are beneficial to organizational development.

Therefore, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 3.

The association between interpersonal intelligence and organizational citizenship behaviors is positive and significant. The higher the interpersonal intelligence, the higher the organizational citizenship behavior.

2.5. Moderating Effect of Interpersonal Intelligence between Belief in a Just World and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

According to social exchange theory, people engage in interdependent and contingent actions that generate reciprocal exchange obligations and resources between two or more parties [34]. Social exchange theory can be viewed as a multidisciplinary paradigm that describes how multiple resources are exchanged according to specific rules, and how this exchange produces high-quality relationships [34]. Therefore, employees with belief in a just world believe that they can be rewarded by engaging in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), which benefits both the employee and the organization. The belief in a just world will lead employees to redefine their work relationship as a social exchange, and organizational citizenship behavior as an exchangeable resource. Furthermore, the belief in a just world makes employees have a certain degree of trust in the organization, making social exchange relationships more feasible, and thus promoting organizational citizenship behavior. In contrast to the multidisciplinary paradigm described above, contemporary theory draws on Blau’s views and focuses on social exchange promoted by interpersonal relationships [35]. Employees use interpersonal relationships as a driving force for exchange. A high level of interpersonal intelligence can promote the exchange of belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior, that is, the higher the belief in a just world, the more organizational citizenship behavior employees are willing to demonstrate, which is conducive to work efficiency. Given that employee social exchange relationships are based on interpersonal intelligence, organizational citizenship behavior is necessarily influenced by employees’ justice beliefs and interpersonal intelligence.

Organizational citizenship behaviors can promote employees’ professionalism, enhance productivity, create a better working environment, and benefit organizations in many other ways [36]. Therefore, the study of organizational citizenship behaviors is important for the development and growth of enterprises. As a concept of fairness, the belief in a just world encourages employees to regard their world as fair, to build trust in others and social institutions, and to perceive the significance of events in life to maintain a positive working attitude and promote positive behaviors in employees [37]. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to understand and create differences and respond effectively to various interpersonal cues, including social sensitivity, social insights, social communication, and altruistic behaviors. Previous theoretical and empirical studies have found that individuals with low interpersonal intelligence have few friends in various social groups and prefer to study or work alone. They are indifferent to other people’s affairs, tend to care more about personal interests than collective benefits, and often do not perform actions for tasks beyond their own responsibilities [38,39]. This problem urged us to explore the regulating role of interpersonal intelligence. Based on the above discussions, we will explore the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence.

Therefore, this paper proposes the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 4.

Interpersonal intelligence plays a moderating role between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behaviors.

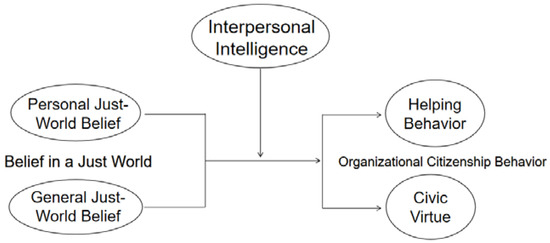

Based on the above ideas, the proposed research model of the study is shown in Figure 1, which demonstrates all of the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

3. Method

3.1. Research Approach

We used an empirical research method, namely, a questionnaire survey, in this study. The content of the questionnaire included questions regarding belief in a just world, organizational citizenship behavior, and interpersonal intelligence. All instruments were psychometrically sound, as evidenced by the sufficient reliabilities of the scales used in the current study. A self-constructed demographic survey was used to obtain information about participants, including sex, age, marital status, educational level, working years, and rank.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The data were collected from employees of 15 different enterprises in Sichuan, Hangzhou and Guizhou, China. This research was conducted in 2021, and the aims of the study were introduced to all respondents at the start of the questionnaire in the guidelines drafted; moreover, according to the ethical rules of research, respondents were told that their provided information would not be revealed to anyone and would solely be used for research purposes. The respondents were chosen using a convenience sampling method. A total of 230 questionnaires were distributed, excluding those that did not meet the requirements, and finally 193 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a recovery rate of 84%. The detail of the demographics in this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.3. Measurements

3.3.1. Belief in a Just World Scale

The Belief in a Just World Scale, which consists of 13 items, is used to measure an individual’s perceptions of fairness [40]. The scale is based on the BJW scale compiled by Dalbert [41], and it has good reliability and validity among Chinese college students. It includes the General Just-World Belief subscale and the Personal Just-World Belief subscale, in which items 1–6 consider the dimensions of general just-world belief and items 7–13 are the dimensions of personal just-world belief. Each question has a 7-option rating scale ranging from strongly disagree 1 to completely agree 7. Higher scores indicate higher levels of belief in a just world. The internal consistency of the scale is satisfactory (α = 0.932).

3.3.2. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale

Podsakoff et al. constructed the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale in 1997 [42]. It consists of 10 items, including two dimensions of helping behavior and civic virtue, among which, items 1–7 are the dimensions of helping behavior and items 8–10 are the dimensions of civic virtue. The scale has a 7-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree 1 to completely agree 7. After summing the overall answers, a higher score represents more willingness to show organizational citizenship behavior. The internal consistency for the scale is high (α = 0.925).

3.3.3. Interpersonal Intelligence Scale

In this study, we used the Interpersonal Intelligence Scale to extract some items from the Positive Organizational Behavior Scale revised by Lu to measure the individual’s interpersonal relationships [43], thereby investigating the individual’s interpersonal intelligence level. The scale comprises 4 items with a 5-point rating scale ranging from completely disagree 1 to completely agree 5. The higher the score, the higher the individual’s interpersonal intelligence level. The scale has sufficient reliability of 0.897.

All items that we used in the questionnaire are given in Appendix A.

4. Results

The data from the filled survey questionnaires were entered into the SPSS file. The data with outliers were deleted in the whole line, and the missing values were processed by the method of mean substitution. Three different methods of data analysis were performed on the primary data. Firstly, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the psychometric properties—reliability and validity—of the constructs in the survey instrument. Secondly, descriptive and correlational analysis was performed to identify and describe sample demographic characteristics, such as mean, standard deviation, and correlational analysis. Thirdly, to test the hypotheses, regression analysis was used. This study collects data of continuous variables and isometric scales. The assumed relationship between variables is the assumption of causal inference, so regression analysis is used to analyze the data. In addition, because this study assumes that the relationship between variables has a moderating effect, and according to Kenny and Judd in 1984, the product of measured variables can be used as an indicator of the interaction of latent variables. This process is relatively simple and scientific to implement in multiple regression [44]. Therefore, regression analysis was used in this study to test the hypothesis. All analyses were performed through the SPSS 21.0 and Amos 26.0.

4.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

Psychometric testing is the evaluation of the amount of error in any instrument. Reliability and validity are two important, generally accepted properties in this regard. It is highly recommended to psychometrically test an instrument before its utilization [45]. Reliability of an instrument refers to the property of consistency of a measure. The validity, on the other hand, refers to how well the observed variables accurately calculate their respective construct [46]. Construct validity includes its convergent validity—the property of observed variables being related [47]. Cronbach’s alpha (CA) values of 0.70 and higher are considered accurate. All constructs were valid as their CA values were above 0.70. For all constructs, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were greater than 0.50. Below mentioned Table 2 displays the Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted results, and associated model fit indices. It can be seen from the data in the table that the NFI, IFI, and CFI values of each scale are all greater than 0.9, CMIN/DF are all within 2, and RMSEA are all below 0.08. reflecting that the model fits are almost fine. Based on the acceptable values for all indicators, all constructs in the analyzed model were reliable and valid.

Table 2.

Convergent validity, reliability, and model fitness.

We confirm the elimination of the collinearity problem in evaluating structural equation modeling (SEM). The VIF (variance inflation factor) value above five may have some collinearity problem between the factorial dimensions. In our study, the VIF value of SEM is less than 5, which is between 1.000 and 2.234. Therefore, it was concluded that there was no collinearity issue among dimensions. The collinearity analyses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Collinearity analysis.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Analysis

The scales were tested for their reliability, and the analysis for reliability was conducted using SPSS-21. The value of alpha was obtained as the indicator of scales reliability. The standard value of alpha is 0.70 and higher. Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, alpha reliabilities, and ranges of all the scales and subscales used in the study. The results indicated that all scales and subscales achieved a satisfactory alpha level ranging from 0.75 to 0.93.

Table 4.

Descriptive and psychometric properties (N = 193).

4.3. Correlation Analysis

Table 5 shows a significant positive relationship between the belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior in which the general and personal just-world beliefs were significantly positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior. The results also revealed a positive correlation between interpersonal intelligence and belief in a just world. Organizational citizenship behavior was positively related to interpersonal intelligence, among which, helping behavior and civic virtue were significantly positively related to interpersonal intelligence.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix for all variables (N = 193).

4.4. Regression Analysis

Regression analysis of this study was performed using the SPSS-21 to examine the directional dependence of the variables. The results of hierarchical regression analysis showed the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior. In Table 6 the first model (F = 139.48, p < 0.001) showed that belief in a just world was a positive predictor of organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.612, t = 11.81, p < 0.001). This model indicated that 41.9% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior could be attributed to the belief in a just world (ΔR2 = 0.419, ΔF = 139.48, p < 0.001). The second model was found to be a significant model (F = 164.81, p < 0.001) that was responsible for 21.1% of the variation in organizational citizenship behavior due to interpersonal intelligence (ΔR2 = 0.211, ΔF = 110.32, p < 0.001), and interpersonal intelligence had a positive predictive effect on organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.786, t = 10.50, p < 0.001).

Table 6.

Analysis of the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior (N = 193).

The third model was the final moderation model, where the product of belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence was used for investigating the moderating role of interpersonal intelligence between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior. The overall model was significant (F = 115.00, p < 0.001) and showed a significant interactive effect of the belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.107, t = −2.50, p < 0.05). This final model of investigation explained an additional 1% of the variation in organizational citizenship behavior (ΔR2 = 0.01, ΔF = 6.27, p < 0.05).

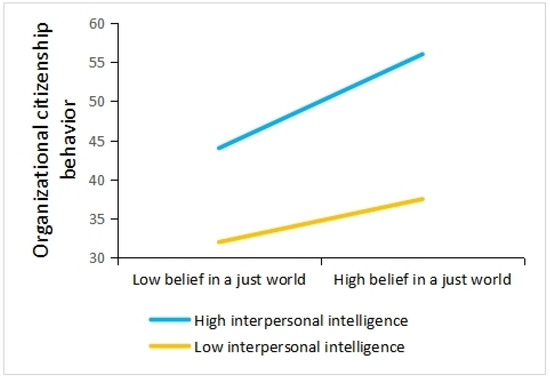

Figure 2 depicts the predicted level of organizational citizenship behavior as an outcome of the level of interpersonal intelligence in employees with strong and weak levels of belief in a just world. The slopes for high and low levels of interpersonal intelligence indicate positive moderation between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior. The figure shows that as the level of interpersonal intelligence decreased, the positive predictive effect of belief in a just world on organizational citizenship behavior tended to gradually decrease. In other words, for individuals with high levels of interpersonal intelligence, their organizational citizenship behavior was more susceptible to the influence of their belief in a just world.

Figure 2.

Interaction between belief in a just world(BJW) and interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behavior(OCB).

Table 7 shows the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior using the hierarchical regression analysis. The first model (F = 112.37, p < 0.001) showed that personal just-world belief was a positive predictor of organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.563, t = 10.60, p < 0.001). This model indicated that 36.7% of the variance could be attributed to personal just-world belief (ΔR2 = 0.367, ΔF = 112.37, p < 0.001). The second model was also found to be a significant model (F = 149.88, p < 0.001), showing positive prediction of interpersonal intelligence in relation to organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.830, t = 10.88, p < 0.001). This model indicated that 24.1% of the variance could be attributed to interpersonal intelligence (ΔR2 = 0.241, ΔF = 118.35, p < 0.001). The third model was the final moderation model, where the product of personal just-world belief and interpersonal intelligence was entered to investigate the moderating influence of interpersonal intelligence between personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The overall model was significant (F = 104.59, p < 0.001) and showed a significant negative interactive effect of interpersonal intelligence and personal just-world belief on organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.105, t = −2.46, p <0.05). The final model explained an additional 1% variance in organizational citizenship behavior (ΔR2 = 0.01, ΔF = 6.04, p < 0.05).

Table 7.

Analysis of the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior (N = 193).

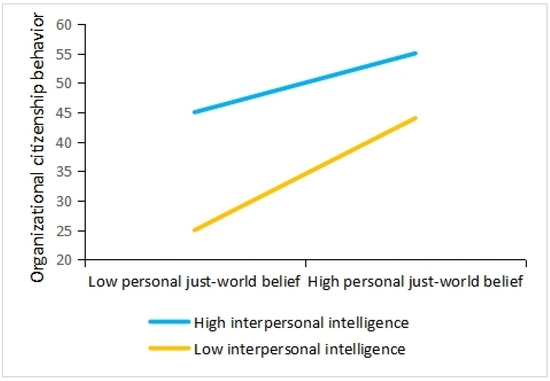

Figure 3 displays the interactive slope for interpersonal intelligence in the relationship with personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The slope for high and low levels of interpersonal intelligence indicated positive moderation between personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The figure shows that when the level of interpersonal intelligence was low, organizational citizenship behavior was more susceptible to a personal just-world belief, whereas for individuals with high levels of interpersonal intelligence, personal just-world belief had no significant positive impact on organizational citizenship behavior.

Figure 3.

Interaction between personal just-world and interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behavior(OCB).

Table 8 shows the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior using the hierarchical regression analysis. The first model (F = 109.91, p < 0.001) showed that a general just-world belief was a positive predictor of organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.503, t = 10.48, p < 0.001). This model showed that 36.2% of the variance could be attributed to general just-world belief (ΔR2 = 0.362, ΔF = 109.91, p < 0.001). The second model was also significant (F = 158.35, p < 0.001), showing a positive prediction of the effects of interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.837, t = 11.47, p < 0.001). This model indicated that 25.9% of the variance could be attributed to interpersonal intelligence (ΔR2 = 0.259, ΔF = 131.62, p < 0.001). The third model was the final moderation model, where the product of general just-world belief and interpersonal intelligence was entered for investigating the moderating influence of interpersonal intelligence in the relationship between general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The overall model was significant (F = 110.15, p < 0.001) and showed a significant negative interactive effect of interpersonal intelligence and general just-world belief on organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.098, t = −2.41, p < 0.05). This final model explained an additional 0.9% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior (ΔR2 = 0.009, ΔF = 5.79, p < 0.05).

Table 8.

Analysis of the moderating effect of interpersonal intelligence between general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior (N = 193).

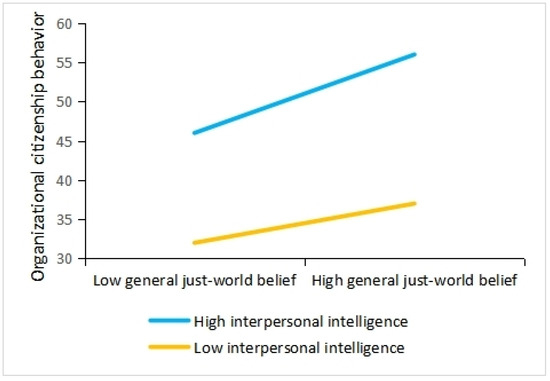

Figure 4 displays the interactive slopes for interpersonal intelligence in relation to general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The slope for high and low levels of interpersonal intelligence indicates positive moderation between general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behavior. The figure shows that as the level of interpersonal intelligence decreased, the positive predictive effect of general just-world belief on organizational citizenship behavior gradually decreased. In other words, for employees with a high level of interpersonal intelligence, their general just-world belief had a significant positive impact on organizational citizenship behavior, whereas for employees with a low level of interpersonal intelligence, their general just-world belief had no significant positive impact on organizational citizenship behavior.

Figure 4.

Interaction between general just-world and interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behavior(OCB).

5. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to explore the relationship between the belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior, and the moderating role of interpersonal intelligence between them. Correlation analysis verified the existence of a significant positive correlation between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior. The regression analysis results indicated that belief in a just world had a significant positive predictive effect on organizational citizenship behavior, which is consistent with the findings of Farh and Moorman, who reported that fairness indicators can better predict organizational citizenship behaviors, and employees who are treated fairly are more likely to exhibit extra-role behaviors [28,31]. Moreover, based on social exchange theory, researchers discovered that employees who are well-treated by organizations are rewarded through engaging in organizational citizenship behaviors [32]. In other words, if employees feel they are treated fairly, they may have a positive attitude toward their work, results, and supervisors, and are more willing to exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors. Similarly, the results of this study are also consistent with social exchange theory [48]. Employees with high belief in a just world believe that they can acquire some rewards by participating in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Additionally, previous studies have shown that belief in a just world has a significant positive impact on altruistic behaviors and prosocial behaviors [49,50,51]. That is, individuals with a strong belief in a just world are more inclined to exhibit prosocial behaviors. As a kind of altruistic helping behavior, organizational citizenship behavior is also influenced by a belief in a just world. These findings provide further support for the results of this study. Individuals with belief in a just world think that the world is fair and everyone’s hard work is rewarded accordingly. Thus, they tend to be more willing to exhibit extra-role behaviors that are not required by formal work regulations but are beneficial to the organization and create a working environment that promotes organizational development so that employees can receive more support in their work, cooperate better with colleagues, improve their work quality and efficiency, and receive high-level evaluations from leaders and rewards, such as promotions and salary increases.

We also found a significant positive correlation between the personal and general just-world beliefs and organizational citizenship behaviors; both could positively predict organizational citizenship behavior. Individuals who believe that they are treated fairly or that others are treated fairly, have a sense of security. They hold the view that the world is fair and principled, that good acts will be well rewarded, and are more willing to follow social norms. These individuals are more likely to exhibit helping behaviors [52]. However, the positive predictive effect of personal just-world belief on organizational citizenship behavior was stronger than that of general just-world belief on organizational citizenship behavior. People tend to describe themselves as fairer than others. Good self-perception is a part of one’s self-concept and positively affects one’s behaviors [53]. Personal just-world belief can be interpreted as a personal contract between subjects and the social world in which they live. The more subjects identify with a personal just-world belief, the greater the compulsion of the personal contract [40]. Personal contracts importantly regulate the interdependence between subjects and their social world. The more people believe that they are in a just world, the more they feel obligated to act fairly. Therefore, people with strong personal just-world beliefs are more willing to exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors.

The results further indicated that a positive correlation existed between interpersonal intelligence and organizational citizenship behaviors; the former could positively predict the latter. This result is also in line with social exchange theory [35]; employees with high interpersonal intelligence can obtain good interpersonal relationships by demonstrating organizational citizenship behavior, which is beneficial to both employees and the organization. Previous studies have not linked interpersonal intelligence with organizational citizenship behaviors, but related studies showed that interpersonal intelligence is positively correlated with prosocial behaviors, and individuals with high interpersonal intelligence are more willing to demonstrate prosocial behaviors [54,55]. In enterprises, employees with high interpersonal intelligence often communicate and cooperate well with their colleagues, superiors, and subordinates to maintain good interpersonal relationships. Therefore, these employees are more likely to help their colleagues, cooperate with others and provide contributions, and create a harmonious working environment. The results of this study are consistent with the above assumptions.

According to the results of our moderating effect analysis, interpersonal intelligence significantly moderated the relationship between belief in a just world and organizational citizenship behavior. Many researchers have reported that maintaining good interpersonal relationships will increase individuals’ helping behaviors [56,57,58,59], and individuals with high interpersonal intelligence and a strong belief in a just world can use interpersonal intelligence to communicate with their colleagues, superiors, and subordinates at work, thus fostering sound interpersonal relationships. Therefore, individuals with a strong belief in a just world and high interpersonal intelligence tend to have sound interpersonal relationships; can get along well with their colleagues, superiors, and subordinates; and cooperate better with others. They are more willing to demonstrate some extra-role behaviors that are conducive to organizational development. Although individuals with low interpersonal intelligence maintain a strong belief in a just world, they often feel that their work is thankless because they are not good at communicating with others and cannot maintain good interpersonal relationships, which reduces their willingness to show organizational citizenship behaviors. As a result, a decrease in interpersonal intelligence will erode the positive impact of a just-world belief on organizational citizenship behaviors.

Further analysis indicated that interpersonal intelligence had a moderating effect on the relationship between personal just-world belief and organizational citizenship behaviors, and the relationship between general just-world belief and organizational citizenship behaviors. The organizational citizenship behaviors of employees with low interpersonal intelligence were more susceptible to the influence of personal just-world belief. Individuals with low interpersonal intelligence cannot clearly perceive, experience, or predict whether others are treated fairly. However, they have experience and confidence in whether they are treated fairly. They can consider others from their own point of view. Therefore, when they have a strong personal just-world belief, that is, they believe that what they have encountered is fair, they will hold the view that others deserve to be treated fairly as well as themselves. Accordingly, these individuals tend to show kindness to others and are more willing to exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors. For employees with high interpersonal intelligence, their organizational citizenship behaviors are more susceptible to general just-world belief. These employees display problem-solving ability and effective communication skills. They can predict and solve the problems in social interpersonal relationships, exactly understand and predict whether others are treated fairly or not, and are aware of the needs of others. Therefore, they are more willing to offer assistance, which increases the chances of demonstrating organizational citizenship behaviors. Employees are the core force of enterprise development and the key to obtaining competitive advantages. Belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence can help to improve employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors and promote the effective operation and sustainable development of organizations.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents some key findings on the relationship between belief in a just world, organizational citizenship behavior, and interpersonal intelligence, making a significant contribution to the existing literature. This is the first study to show that belief in a just world is significantly positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior, and interpersonal intelligence is positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior. These findings highlight the importance of belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence in enterprise development and further enhance our understanding of employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors. According to the regression analysis, we further found that the predictive effect of just-world belief on organizational citizenship behaviors was influenced by interpersonal intelligence. The level of interpersonal intelligence had a significant impact on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors. This research was based on social exchange theory, and the results of the current study prove that social exchange theory supports the above mentioned relationship.

According to the results of this study, belief in a just world and interpersonal intelligence are key factors affecting organizational citizenship behavior. Organizational citizenship behavior is an important factor to improve the short-term and long-term performance of enterprises, which can bring sustainability to an organization. Therefore, corporate executives first need to focus on cultivating employees’ belief in a just world, and encourage employees’ voluntary extra-role behaviors by creating a fair, harmonious, and win–win organizational cultural atmosphere. Second, top executives should fully use interpersonal intelligence to enhance the effectiveness of the belief in a just world. When training employees, enterprises should also emphasize the cultivation and development of interpersonal intelligence and improve employees’ ability to communicate and collaborate to create a harmonious enterprise environment, thus stimulating employees to devote themselves to the organization. Enterprises should improve employees’ interpersonal skills through management training, and create a fair and just management environment in organizational management, so as to promote employees’ high-level or sustainable organizational citizenship behavior.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study enriches the research achievements in related fields. The practical contribution of this research is to help organizations develop effective training management plans that promote sustainability development to the organization. Despite the contributions, there are a few limitations associated with this research that might affect the interpretation of results. The first limitation was that the respondents were selected only from three regions, which may affect the generalizability of the results under the influence of regional development and environment. Secondly, we adopted a self-reporting method to conduct a questionnaire survey, which may cause common method biases. In future research, we can design a social approval scale to control such effects. Finally, since we used cross-sectional survey data, the influence of just-world belief and interpersonal intelligence on organizational citizenship behaviors may lead to a certain time hysteresis effect. For this reason, future research should include adopting a longitudinal research design to collect research data, conducting a case tracking study with quantitative and qualitative research methds, or designing a longitudinal training intervention experiment based on the improvement of interpersonal intelligence.

Author Contributions

L.H. and H.Z. contributed to the study design and writing the manuscript; L.H. and C.W. performed the data processing and statistical analysis; H.Z. revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Hangzhou Normal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tingting Fu for collecting the data and all the peer reviewers for their excellent suggestions that contributed to improving this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Research Instrument.

Table A1.

Research Instrument.

| Belief in a Just World | |

|---|---|

| 1. | I think the world is basically fair. |

| 2. | To a large extent, I believe people get a lot of what they deserve. |

| 3. | I am convinced that justice always defeats injustice. |

| 4. | In the long run, I believe that those who suffer injustice will be compensated. |

| 5. | I firmly believe in living in all fields (career, family, politics),Injustice is accidental, not inevitable. |

| 6. | I think people will strive for justice before making big decisions. |

| 7. | To a large extent, I believe that many things that happen to me are what I deserve. |

| 8. | I am usually treated fairly. |

| 9. | I believe I usually get what I deserve. |

| 10. | In general, what happened to me was fair. |

| 11. | Injustices that happen in my life are accidental, not inevitable. |

| 12. | I believe that most things that happen in my life are fair. |

| 13. | I think that everything that involves a major decision I make is usually fair. |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | |

| 14. | If there are employees who cannot keep up with their work, they will help. |

| 15. | Willing to share their strengths with other colleagues in the unit. |

| 16. | When other members of the unit disagree, they will try their best to be a moderator. |

| 17. | Willing to spend time helping unit members who have problems at work. |

| 18. | Take measures to avoid conflicts with other members of the unit. |

| 19. | Before doing anything that may affect other members of the unit, we will greet them in advance. |

| 20. | Provide encouragement when other members of the unit are depressed. |

| 21. | Provide constructive suggestions on how to improve the work efficiency of the unit. |

| 22. | Willing to risk dissatisfaction and express what is the best view of the company. |

| 23. | Attend and actively participate in team meetings. |

| Interpersonal Intelligence | |

| 24. | I achieve good interpersonal relationships by being kind and respecting others. |

| 25. | I achieve good interpersonal relationships by inspiring others and treating others honestly. |

| 26. | I achieve good interpersonal relationships through understanding, modest and studious. |

| 27. | I achieve good interpersonal relationships through self-reflection and tolerance of others. |

References

- PKhaola, P.; Rambe, P. The effects of transformational leadership on organizational citizenship behaviour: The role of organizational justice and affective commitment. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 44, 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, R.H. Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Do Fairness Perceptions Influence Employee Citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the Millennium, a Decade Later: A Meta-Analytic Test of Social Exchange and Affect-Based Perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, J.J.; Brockner, J.; Konovsky, M.A.; Price, K.H.; Henley, A.B.; Taneja, A.; Vinekar, V. Commitment, procedural fairness, and organizational citizenship behavior: A multifoci analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, T. Explaining Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: A Critical Review of Social Exchange Perspective. PhD Thesis, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R. Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, F. Interpersonal intelligence and prosocial behavior among elementary school students. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, L.K. How interpersonal synchrony facilitates early prosocial behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J.; Miller, D.T. Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychol. Bull. 1978, 85, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Z.; Pcplan, L.A. Belief in a just world and reaction to another’s lot: A study of participants in the national draft lottery. J. Soc. Issues 1973, 29, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Z.; Peplau, L.A. Who believes in a just world? J. Soc. Issues 2010, 31, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, C. Beliefs in a Just World as a Buffer against Anger. Soc. Justice Res. 2002, 15, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detlef, F.; Gabriele, J.; Frank, B. Belief in a Just World, Causal Attributions, and Adjustment to Sexual Violence. Soc. Justice Res. 2005, 18, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Q. Rev. Biol. 1985, 4, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hajebi, M.; Taheri, S.; Noshadi, M. The Relationship between Interpersonal Intelligence, Reading Activity and Vocabulary Learning among Iranian EFL Learners. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Transl. Stud. 2018, 6, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, R.J.; Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior:The Good Soldier Syndrome. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 294. [Google Scholar]

- Tansky, J.W. Justice and organizational citizenship behavior: What is the relationship? Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1993, 6, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskew, D.E. The role of organizational justice in organizational citizenship behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1993, 6, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Organ, D.W. Dispositional and contextual determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Brown, J.D. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, M. Belief in a just world and altruistic behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 31, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, M.T.; Madey, S.F.; Tillman, T.C.; Wheeler, J. Perceived patient responsibility and belief in a just world affects helping. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Schmidt, S. Dealing with stress in the workplace: Compensatory effects of belief in a just world. Eur. Psychol. 2007, 12, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, K.; Fitzsimons, G.M.; Kay, A.C. Social disadvantage and the self-regulatory function of justice beliefs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.L. Accounting for organizational citizenship behavior: Leader fairness and task scope versus satisfaction. J. Manag. 1990, 16, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Moorman, R.H. Fairness and organizational citizenship behavior: What are the connections? Soc. Justice Res. 1993, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. Citizenship Behavior and Social Exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar]

- Erkutlu, H. The moderating role of organizational culture in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Moorman, R.H. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, N.; Amaliyah, A.R.; Amin, N.; Jufri, M.A. The development of learning devices based on interpersonal intelligence to improve prospective teachers’ social competence. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1321, 022096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hui, C.; Sego, D. The role of organizational citizenship behavior in turnover: Conceptualization and preliminary tests of key hypotheses. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 83, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J. The justice motive: Some hypotheses as to its origins and forms. J. Personal. 2010, 45, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, M. Developing interpersonal intelligence in the workplace. Ind. Commer. Train. 2001, 33, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoda, T.M.; Mcconnell, A.R. Interpersonal sensitivity and self-knowledge: Those chronic for trustworthiness are more accurate at detecting it in others. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. Revising of belief in a just world scale and its reliability and validity in college students. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 2012, 21, 561–563. [Google Scholar]

- Dalbert, C. The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Soc. Justice Res. 1999, 12, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Ahearne, M.; Mackenzie, S.B. Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Research on Guanxi Management of Superior Subordinate, Psychological Ownership and Positive Organizational Behavior: Based on Non-Family Members of Family Business. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Estimating the nonlinear and interactive effects of latent variables. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 96, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, A.M. Psychometric instrumentation: Reliability and validity of instruments used for clinical practice, evidence-based practice projects and research studies. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2015, 29, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Polit, D.F. Assessing measurement in health: Beyond reliability and validity. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Alexandre, N.; Guirardello, E. Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiol. E Serviços De Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roch, S.G.; Shannon, C.E.; Martin, J.J.; John, D.S.; Agosta, P.; Shanock, L.R. Role of employee felt obligation and endorsement of the just world hypothesis: A social exchange theory investigation in an organizational justice context. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroli, M.; Sagone, E. Belief in a just world, prosocial behavior, and moral disengagement in adolescence. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, D.T. Altruism and threat to a belief in a just world. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 13, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bègue, L.; Charmoillaux, M.; Cochet, J.; Cury, C.; Suremain, F.D. Altruistic behavior and the bidimensional just world belief. Am. J. Psychol. 2008, 121, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Du, Z. A Study on the Influence of Beliefs in a Just World and Pro-social Behaviors on Juvenile Delinquency. Juv. Delinq. Prev. Res. 2018, 2, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Farwell, L.; Weiner, B. Self-perception of fairness in individual and group contexts. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 868–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, L.K.; Einarson, K.M.; Trainor, L.J. Interpersonal synchrony increases prosocial behavior in infants. Dev. Sci. 2014, 17, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirelli, L.K.; Wan, S.J.; Trainor, L.J. Fourteen-month-old infants use interpersonal synchrony as a cue to direct helpfulness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. 2014, 369, 20130400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, R.B. Adolescent prosocial behavior: Peer-group and situational factors associated with helping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Mcnamara, C.C. Interpersonal relationships, emotional distress, and prosocial behavior in middle school. J. Early Adolesc. 1999, 19, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, D.; Doyle, A.B.; Brendgen, M. The quality of adolescents’ friendships: Associations with mothers’ interpersonal relationships, attachments to parents and friends, and prosocial behaviors. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kenrick, D.T.; Baumann, D.J. Effects of mood on prosocial behavior in children and adults. Dev. Prosoc. Behav. 1982, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).