“Waging War” for Doing Good? The Fortune Global 500’s Framing of Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Redefining Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Corporate Social Advocacy

2.2. Corporate Social Advocacy and Corporate Pandemic Response Communication

3. Theoretical Framework: Framing the COVID-19 Pandemic Discourse

Research Questions

4. Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Coding Procedures

5. Results

5.1. CSR Communication during the Pandemic

5.1.1. Companies by Country

5.1.2. Companies by Industry

5.1.3. Companies by CSR Placement

5.1.4. Analysis of Corporations by CSR Titles

5.1.5. CSR Annual Reports

5.2. COVID-19 Pandemic Related Information: Placement and Content

5.3. Framing the Corporate Pandemic Discourse: Content Analysis

6. Discussion

“In the next…pandemic, be it now or in the future, be the virus mild or virulent, the single most important weapon against the disease will be a vaccine. The second most important thing will be communication.”—John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History.

7. Conclusions

Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Company | Country | Industry | Years on Fortune 500 List |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Walmart | U.S. | General Merchandisers | 26 |

| 6 | Royal Dutch Shell | Netherlands | Petroleum Refining | 26 |

| 10 | Amazon | U.S. | Internet Services and Retailing | 12 |

| 14 | CVS Health | U.S. | Food & Drug Stores | 25 |

| 23 | AT&T | U.S. | Telecommunications | 26 |

| 25 | Industrial & Commercial Bank of China | China | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 22 |

| 32 | Ford Motor | U.S. | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 26 |

| 34 | Costco Wholesale | U.S. | General Merchandisers | 26 |

| 37 | Chevron | U.S. | Petroleum Refining | 26 |

| 42 | Walgreens Boots Alliance | U.S. | Food & Drug Stores | 26 |

| 45 | Verizon Communications | U.S. | Telecommunications | 26 |

| 48 | Microsoft | U.S. | Computer Software | 23 |

| 60 | Home Depot | U.S. | Speciality Retailers | 26 |

| 66 | China Mobile Communications | China | Telecommunications | 20 |

| 69 | Anthem | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 19 |

| 71 | Citigroup | U.S. | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 26 |

| 78 | General Electric | U.S. | Industrial, Construction & Farm Machinery | 26 |

| 81 | Prudential | U.K. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 25 |

| 88 | Enel | Italy | Utilities | 26 |

| 95 | Softbank Group | Japan | Telecommunications | 13 |

| 96 | Bosch Group | Germany | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 26 |

| 105 | Johnson & Johnson | U.S. | Pharmaceuticals | 20 |

| 120 | Raytheon Technologies | U.S. | Aerospace & Defense | 26 |

| 126 | Freddie Mac | U.S. | Diversified Financials | 24 |

| 128 | Centene | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 5 |

| 138 | Lowe’s | U.S. | Speciality Retailers | 23 |

| 139 | Intel | U.S. | Electronics & Electrical Equipment | 26 |

| 150 | MetLife | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 26 |

| 152 | Indian Oil | India | Petroleum Refining | 26 |

| 168 | Prudential Financial | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 26 |

| 178 | Toyota Tsusho | Japan | Trading | 12 |

| 180 | Sysco | U.S. | Wholesalers: Food and Grocery | 26 |

| 198 | Tencent Holdings | China | Internet Services and Retailing | 4 |

| 207 | Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group | China | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 8 |

| 222 | State Bank of India | India | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 15 |

| 237 | Idemitsu Kosan | Japan | Petroleum Refining | 26 |

| 255 | Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria | Spain | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 26 |

| 258 | American Airlines Group | U.S. | Airlines | 26 |

| 264 | Allstate | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 25 |

| 279 | Liberty Mutual Insurance Group | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 26 |

| 280 | Accenture | Ireland | Information Technology Services | 19 |

| 283 | GlaxoSmithKline | U.K. | Pharmaceuticals | 26 |

| 291 | China United Network Communications | China | Telecommunications | 12 |

| 292 | Deutsche Bank | Germany | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 26 |

| 294 | UBS Group | Switzerland | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 26 |

| 298 | Bunge | U.S. | Food Products and Beverages | 18 |

| 309 | Shandong Weiqiao Pioneering Group | China | Textiles | 9 |

| 314 | Fresenius | Germany | Health Care: Medical Facilities | 11 |

| 329 | CK Hutchison Holdings | China | Speciality Retailers | 5 |

| 338 | Tata Motors | India | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 11 |

| 356 | USAA | U.S. | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 7 |

| 357 | Fujitsu | Japan | Information Technology Services | 26 |

| 358 | Credit Suisse Group | Switzerland | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 26 |

| 361 | LyondellBasell Industries | Netherlands | Chemicals | 13 |

| 375 | Cathay Financial Holding | Taiwan | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 19 |

| 391 | Suzuki Motor | Japan | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 26 |

| 393 | China Taiping Insurance Group | China | Insurance: Health Care and Property | 3 |

| 396 | Compass Group | U.K. | Food Products and Beverages | 19 |

| 397 | Compal Electronics | Taiwan | Computers, Office Equipment | 9 |

| 403 | Toshiba | Japan | Electronics & Electrical Equipment | 25 |

| 405 | SAP | Germany | Computer Software | 5 |

| 409 | Medtronic | Ireland | Medical Products and Equipment | 4 |

| 415 | Takeda Pharmaceutical | Japan | Pharmaceuticals | 1 |

| 420 | Anglo American | U.K. | Mining, Crude-Oil Production | 19 |

| 427 | KB Financial Group | South Korea | Banks: Commercial and Savings | 8 |

| 430 | Shougang Group | China | Metals | 9 |

| 433 | BT Group | U.K. | Telecommunications | 26 |

| 436 | Haier Smart Home | China | Electronics & Electrical Equipment | 3 |

| 445 | Linde | U.K. | Chemicals | 1 |

| 446 | Sumitomo Electric Industries | Japan | Motor Vehicles & Parts | 26 |

| 471 | East Japan Railway | Japan | Railroads | 26 |

| 475 | Heineken Holding | Netherlands | Food Products and Beverages | 14 |

| 476 | X5 Retail Group | Netherlands | Food & Drug Stores | 1 |

| 479 | Starbucks | U.S. | Food Products and Beverages | 1 |

| 485 | Adecco Group | Switzerland | Diversified Outsourcing Services | 22 |

| 488 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | U.S. | Pharmaceuticals | 17 |

References

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D.W. Conceptualizing and measuring “corporate social advocacy” communication: Examining the impact on corporate financial performance. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Limaye, R.J.; Sauer, M.; Ali, J.; Bernstein, J.; Wahl, B.; Barnhill, A.; Labrique, A. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, M.; Oberoi, R.; Halsall, J.P. Reaffirming trust in social enterprise in the COVID-19 era: Ways forward. Corp. Gov. Sustain. Rev. 2021, 5, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman. The 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer Spring Update: Trust and the Covid-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/research/trust-2020-spring-update (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- O’Connor, A.; Parcha, J.M.; Tulibaski, K.L. The institutionalization of corporate social responsibility communication: An intra-industry comparison of MNCs’ and SMEs’ CSR reports. Manag. Commun. Q. 2017, 31, 503–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B.; Lipartito, K.J.; Post, J.E.; Werhane, P.H.; Goodpaster, K.E. Corporate Responsibility: The American Experience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Business and Society: Environment and Responsibility, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, E. How Companies Can Partner with Governments to Distribute Covid Vaccine Efficiently and Effectively. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/edwardsegal/2021/01/21 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Park, D.J.; Berger, B.K. The Presentation of CEOs in the Press, 1990–2000: Increasing Salience, Positive Valence, and a Focus on Competency and Personal Dimensions of Image. J. Public Relat. Res. 2004, 16, 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, L.; Gaither, B.; Gaither, T.K. Corporate social advocacy as public interest communications: Exploring perceptions of corporate involvement in controversial social-political issues. J. Public Interest Commun. 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L.; van Tuijl, P. Political Responsibility in Transnational NGO Advocacy. World Dev. 2000, 28, 2051–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Towards clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. In McQuail’s Reader in Mass Communication Theory; Sage: London, UK, 1993; pp. 390–397. [Google Scholar]

- Overton, H.K. Examining the impact of message frames on information seeking and processing: A new integrated theoretical model. J. Commun. Manag. 2018, 22, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11. Political Commun. 2003, 20, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallahan, K. Political Public Relations and Strategic Framing. In Political Public Relations: Principles and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 177–213. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Vieira, E.T. Striving for Legitimacy Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Insights from Oil Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Shumate, M. An Economic Industry and Institutional Level of Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility Communication. Manag. Commun. Q. 2010, 24, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Schulz-Knappe, C. Credible corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication predicts legitimacy: Evidence from an experimental study. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S. Creating Corporate Accountability: Foundational Principles to Make Corporate Citizenship Real. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlen, Ø. Corporate Social Responsibility. In Encyclopedia of Public Relations; Heath, R.L., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, M.J.; Grisby, D.W. Strategic Management. In Total Quality & Global Competition; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffary, S.; Del Rey, J. The Big Tech Antitrust Report Has One Big Conclusion: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google Are Anti-Competitive. Available online: https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/10/6/21505027/congress-big-tech-antitrust-report-facebook-google-amazon-apple-mark-zuckerberg-jeff-bezos-tim-cook (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Uysal, N. On the relationship between dialogic communication and corporate social performance: Advancing dialogic theory and research. J. Public Relat. Res. 2018, 30, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, G.; Christensen, L.T. Organizational identity: Linkages between internal and external communication. In The New Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods; Jablin, F., Putnam, L., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 231–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdora-Aksak, E. An Analysis of Turkey’s Telecommunications Sector’s Online Presence: How Corporate Social Responsibility Contributes to Organizational Identity Construction. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdora-Aksak, E.; Atakan-Duman, S. Gaining legitimacy through CSR: An analysis of Turkey’s 30 largest corporations. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Gabriel, K.P. Understanding employee responses to COVID-19: A behavioral corporate social responsibility perspective. Manag. Responsib. 2020, 18, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, F.; Walter, H. The keys to rethinking corporate philanthropy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Wowak, A.J. CEO sociopolitical activism: A stakeholder alignment model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Watson, B.; Gardner, J.; Gallois, C. Organizational communication: Challenges for the new century. J. Commun. 2004, 54, 722–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Where is CSR Info Located | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| At the main menu | 302 | 65.9% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “About Us” | 47 | 9.4% |

| At the footer of the homepage, under “About Us” | 25 | 5% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “Company” | 22 | 4.4% |

| At the footer of the homepage, under “Company” | 12 | 2.4% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “Investors” | 8 | 1.6% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “About Us”, under “Sustainability/Impact/Values” | 8 | 1.6% |

| At the footer of the homepage | 8 | 1.6% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “Who are we” | 7 | 1.4% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “About Us”, under “Corporate/Company Info” | 6 | 1.2% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “Reports or Publications” | 5 | 1% |

| Under the dropdown “News and Media Center” | 3 | 0.6% |

| At the main menu, under the dropdown “About Us”, under “Media and Reporting” | 3 | 0.6% |

| At the footer of the homepage, under “Work with Us or Contact Us” | 2 | 0.4% |

| Total | 458 | 100% |

| CSR Info Not Accessible | n | |

| Website not accessible | 22 | |

| No CSR Info available | 20 | |

| Total | 42 of 500 | |

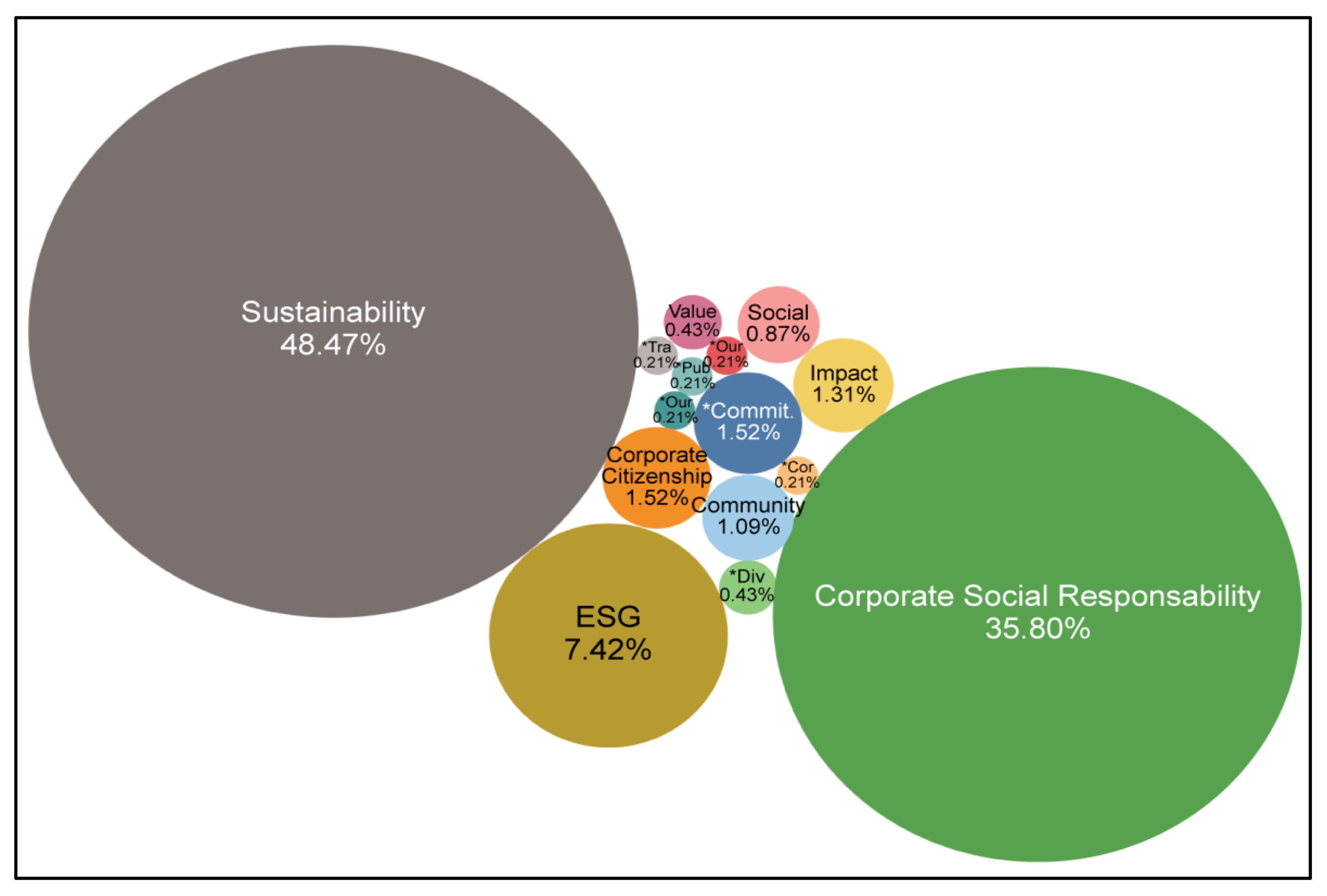

| What is CSR Page Titled | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 222 | 48.47% |

| Corporate Social Responsibility | 164 | 35.81% |

| ESG | 34 | 7.42% |

| Corporate Citizenship | 7 | 1.53% |

| Commitments | 7 | 1.53% |

| Impact | 6 | 1.31% |

| Community | 5 | 1.09% |

| Social | 4 | 0.87% |

| Value | 2 | 0.44% |

| Diversity and Inclusion | 2 | 0.44% |

| Transparency and Accountability | 1 | 0.22% |

| Public Welfare | 1 | 0.22% |

| Our Purpose | 1 | 0.22% |

| Our Philanthropy | 1 | 0.22% |

| Corporate Philosophy | 1 | 0.22% |

| Total | 458 | 100% |

| CSR Page Not Accessible | n | |

| Website not accessible | 22 | |

| n/a | 20 | |

| Total | 42 of 500 | |

| CSR Report Availability | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 325 | 70.9% |

| Doesn’t exist | 67 | 14.6% |

| Not up-to-date | 66 | 14.4% |

| Total | 458 | 100% |

| CSR Page Not Accessible | n | |

| Website not accessible | 22 | |

| n/a | 20 | |

| Total | 42 of 500 | |

| COVID Mentioned in CSR | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| When searched for | 207 | 43.3% |

| None | 171 | 35.7% |

| Under CSR | 76 | 15.8% |

| Context Only | 24 | 5.2% |

| Website not accessible | 22 | |

| Total | 478 | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uysal, N.; Aksak, E.O. “Waging War” for Doing Good? The Fortune Global 500’s Framing of Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053012

Uysal N, Aksak EO. “Waging War” for Doing Good? The Fortune Global 500’s Framing of Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053012

Chicago/Turabian StyleUysal, Nur, and Emel Ozdora Aksak. 2022. "“Waging War” for Doing Good? The Fortune Global 500’s Framing of Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053012

APA StyleUysal, N., & Aksak, E. O. (2022). “Waging War” for Doing Good? The Fortune Global 500’s Framing of Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(5), 3012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053012