Does Government-Led Publicity Enhance Corporate Green Behavior? Empirical Evidence from Green Xuanguan in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literatures and Theoretical Model

2.1. Informative Publicity and Corporate Behavior

2.2. Internal Perception and Corporate Behavior

2.3. External Environment Perception and Corporate Behavior

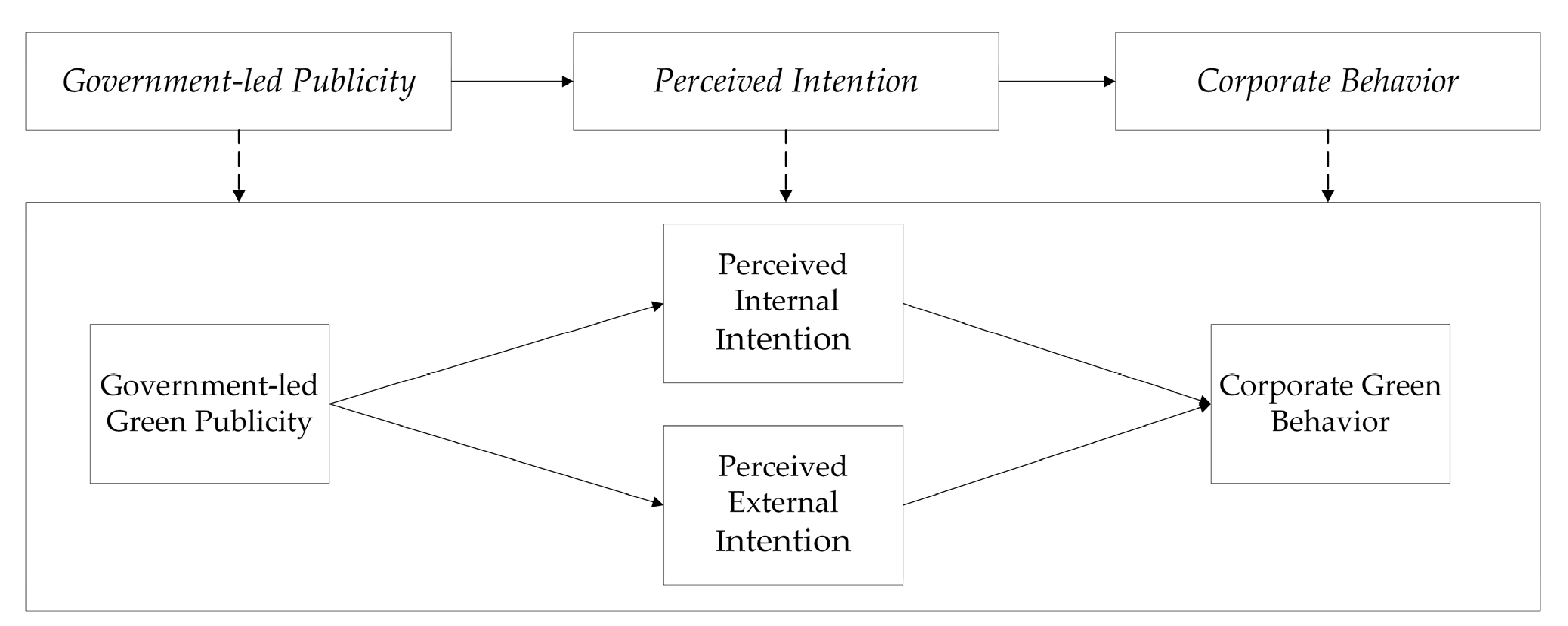

2.4. Model Specification

3. Data and Method

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

4.2. Empirical Results

| Hypothesis | Path | St. Coefficient | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Xuanguan → PG opportunity | 0.71 | 0.36 | *** | Accept |

| PG opportunity → corporate green behavior | 0.50 | *** | |||

| H2 | Xuanguan → PG risk | 0.54 | 0.10 | *** | Accept |

| PG risk → corporate green behavior | 0.18 | ** | |||

| H3 | Xuanguan → PGI of competitor | 0.63 | 0.24 | *** | Accept |

| PGI of competitor → corporate green behavior | 0.38 | *** | |||

| H4 | Xuanguan → PGI of territorial government | 0.59 | 0.07 | *** | Accept |

| PGI of territorial government → corporate green behavior | 0.12 | * | |||

4.3. Subgroup-Based Analysis

4.4. Further Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Latent Variable | Indicators | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Xuanguan | 4 | 0.883 |

| PG Opportunity | 5 | 0.868 |

| PG Risk | 4 | 0.901 |

| PGI of competitor | 4 | 0.806 |

| PGI of territorial government | 4 | 0.892 |

| GTI | 5 | 0.905 |

| GPP | 5 | 0.860 |

| GM | 7 | 0.893 |

| GER | 6 | 0.924 |

| Latent Variable | Indicators | KMO | Bartlett Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | DF | Sig | |||

| Xuanguan | 4 | 0.806 | 446.962 | 6 | 0.000 |

| PG Opportunity | 5 | 0.884 | 579.818 | 10 | 0.000 |

| PG Risk | 4 | 0.823 | 372.488 | 6 | 0.000 |

| PGI of competitor | 4 | 0.837 | 406.347 | 6 | 0.000 |

| PGI of territorial government | 4 | 0.839 | 453.288 | 6 | 0.000 |

| GTI | 5 | 0.893 | 595.313 | 10 | 0.000 |

| GPP | 5 | 0.858 | 412.359 | 10 | 0.000 |

| GM | 7 | 0.907 | 669.395 | 21 | 0.000 |

| GER | 6 | 0.909 | 838.824 | 15 | 0.000 |

| Latent Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Accumulative Contribution Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuanguan | 1 | 0.919 | 74.074% | |

| 2 | 0.823 | |||

| 3 | 0.817 | |||

| 4 | 0.880 | |||

| PG Opportunity | 1 | 0.850 | 71.799% | |

| 2 | 0.833 | |||

| 3 | 0.816 | |||

| 4 | 0.876 | |||

| 5 | 0.861 | |||

| PG Risk | 1 | 0.845 | 71.732% | |

| 2 | 0.859 | |||

| 3 | 0.834 | |||

| 4 | 0.849 | |||

| PGI of territorial government | 1 | 0.897 | 75.703% | |

| 2 | 0.847 | |||

| 3 | 0.869 | |||

| 4 | 0.867 | |||

| PGI of competitor | 1 | 0.873 | 73.667% | |

| 2 | 0.868 | |||

| 3 | 0.852 | |||

| 4 | 0.841 | |||

| Corporate Green Behavior | GTI | 1 | 0.864 | 66.372% |

| 2 | 0.811 | |||

| 3 | 0.808 | |||

| 4 | 0.770 | |||

| 5 | 0.780 | |||

| GPP | 1 | 0.826 | ||

| 2 | 0.713 | |||

| 3 | 0.603 | |||

| 4 | 0.727 | |||

| 5 | 0.582 | |||

| GM | 1 | 0.846 | ||

| 2 | 0.677 | |||

| 3 | 0.741 | |||

| 4 | 0.709 | |||

| 5 | 0.767 | |||

| 6 | 0.606 | |||

| 7 | 0.530 | |||

| GER | 1 | 0.903 | 72.358% | |

| 2 | 0.849 | |||

| 3 | 0.852 | |||

| 4 | 0.793 | |||

| 5 | 0.827 | |||

| 6 | 0.876 | |||

| Item | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pass Standard | <3 | >0.9 | <0.1 | >0.5 | >0.7 |

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Government-led Green Publicity

- 2.

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Green Intention (group)

| Latent Variable | Indicators | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG Opportunity | 5 | 1.501 | 0.996 | 0.050 | 0.648 | 0.902 |

| PG Risk | 4 | 2.298 | 0.993 | 0.081 | 0.623 | 0.869 |

| PGI of competitor | 4 | 0.427 | 1 | 0 | 0.650 | 0.881 |

| PGI of territorial government | 4 | 0.874 | 1 | 0 | 0.677 | 0.893 |

- 3.

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Corporate Green Behavior

| 1st Order Latent Variable | Indicators | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTI | 5 | 0.198 | 1 | 0 | 0.658 | 0.906 |

| GPP | 5 | 1.796 | 0.99 | 0.063 | 0.553 | 0.861 |

| GM | 7 | 1.904 | 0.981 | 0.068 | 0.544 | 0.893 |

| Variable | Item | Standard Factor Loading | C.R. | p | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Green Behavior | GTI | 0.655 | 0.691 | 0.868 | ||

| GPP | 0.848 | 7.492 | *** | |||

| GM | 0.962 | 6.979 | *** | |||

| GTI | GTI_1 | 0.870 | 0.659 | 0.906 | ||

| GTI_2 | 0.760 | 12.8 | *** | |||

| GTI_3 | 0.829 | 14.713 | *** | |||

| GTI_4 | 0.771 | 13.088 | *** | |||

| GTI_5 | 0.823 | 14.549 | *** | |||

| GPP | GPP_1 | 0.706 | 0.552 | 0.86 | ||

| GPP_2 | 0.792 | 10.247 | *** | |||

| GPP_3 | 0.732 | 9.519 | *** | |||

| GPP_4 | 0.718 | 9.354 | *** | |||

| GPP_5 | 0.764 | 9.909 | *** | |||

| GM | GM_1 | 0.777 | 0.544 | 0.893 | ||

| GM_2 | 0.692 | 10.017 | *** | |||

| GM_3 | 0.744 | 10.904 | *** | |||

| GM_4 | 0.701 | 10.162 | *** | |||

| GM_5 | 0.769 | 11.339 | *** | |||

| GM_6 | 0.773 | 11.415 | *** | |||

| GM_7 | 0.703 | 10.209 | *** |

- 4.

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Environmental Regulation

| Latent Variable | Indicators | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GER | 6 | 2.461 | 0.984 | 0.086 | 0.670 | 0.924 |

References

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China. The Industrial Green Development Plan in the 14th Five Year Plan; Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.D. Thoughts and Suggestions on the Green Development of Industry during the 14th Five-Year Plan; China Center for Information Industry Development: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.J.; Chen, W. Environmental Regulation, Green Innovation, and Industrial Green Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Spatial Durbin Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, K.R.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Yao, X. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: The road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, K.; Kilgour, D.M.; Hipel, K.W. Systematic policy development to ensure compliance to environmental regulations. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1994, 24, 1289–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorie, M.; Simpson, S.S.; Cohen, M.A.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Examining Procedural Justice and Legitimacy in Corporate Offending and Beyond-Compliance Behavior: The Efficacy of Direct and Indirect Regulatory Interactions. Law Policy 2018, 40, 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How Green Human Resource Management Can Promote Green Employee Behavior in China: A Technology Acceptance Model Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, L.R.; Li, J.K. Why Low-Carbon Publicity Effect Limits? The Role of Heterogeneous Intention in Reducing Household Energy Consumption. Energies 2021, 14, 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Binder, M.; Blankenberg, A.K. Green behavior, green self-image, and subjective well-being: Separating affective and cognitive relationships. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 179, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, G.M. NUDGE: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2009, 8, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosters, M.; Van der Heijden, J. From mechanism to virtue: Evaluating Nudge theory. Evaluation 2015, 21, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spotts, H.E.; Weinberger, M.G.; Weinberger, M.F. Publicity and Advertising: What Matters Most for Sales? Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1986–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen; Philip, J. Public relations in the promotional mix: A three-phase analysis. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1996, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Social and environmental reporting and the corporate ego. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2009, 18, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Morales, V.J.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Verdu-Jover, A.J. Antecedents and consequences of organizational innovation and organizational learning in entrepreneurship. Ind. Manag. Data. Syst. 2006, 106, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bundy, J.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Short, C.; Coombs, T. Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, Interpretation, and Research Development. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1661–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, M.; Luciano, P. Emerging market orientation: Advertising and promotion in the French telecommunications sector: 1952-2002. J. Hist. Res. Mark. 2021, 13, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Du, J.G.; Long, H.Y. Green Development Behavior and Performance of Industrial Enterprises Based on Grounded Theory Study: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, Y.K.; Chen, Z. Analysis of the momentum for construction enterprises to improve safety producing behavior. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Logistics Systems and Intelligent Management (ICLSIM), Harbin, China, 9–10 January 2010; Volume 3, pp. 1835–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; An, Y. Analyzing influencing factors of green transformation in China’s manufacturing industry under environmental regulation: A structural equation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of environmental regulations on green technological innovative behavior: An empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.X.; Zhao, C.H. Impact of media reports on innovative behaviours of photovoltaic enterprises: Experience view from China. Light Eng. 2018, 26, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Yu, B.Y.; Wang, J.W.; Wei, Y.M. Impact factors of household energy-saving behavior: An empirical study of Shandong Province in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Chan, K.C.; Dong, M.; Yao, Q. The impact of economic policy uncertainty on a firm’s green behavior: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 59, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.Q.; Wang, Q.W. Can environmental regulation directly promote green innovation behavior?—Based on situation of industrial agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.Y.C.; Hao, G.S.; Carter, S. Intertwining Corporate Social Responsibility, Employee Green Behavior, and Environmental Sustainability: The Mediation Effect of Organizational Trust and Organizational Identity. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 2, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan-Mitra, C.S.; Stanca, L.; Dabija, D. Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Klieštik, T.; Novák, A. Internet of Things Smart Devices, Industrial Artificial Intelligence, and Real-Time Sensor Networks in Sustainable Cyber-Physical Production Systems. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 1, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, S.; Huang, K.F. Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Shan, H.; Tikuye, G.A. How Do Stakeholder Pressures Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Adoption? Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2021, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial Marketing Strategy: The Emergence of Corporate Environmentalism as Market Strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donna, M.; Lucy, M.; Paul, M.; Marius, C. Going above and beyond: How sustainability culture and entrepreneurial orientation drive social sustainability supply chain practice adoption. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, A.; Giuliano, N. Seeing ecology and “green” innovations as a source of change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, V.C.; Orlando, T. Sustainable value creation in SMEs: A case study. TQM J. 2013, 25, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, V. Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P.; Kyrgidou, L.P.; Palihawadana, D. Internal Drivers and Performance Consequences of Small Firm Green Business Strategy: The Moderating Role of External Forces. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rawashdeh, A.M. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M.; Piha, L. The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, K.; Akashi, Y.; Lim, J.; Yoshimoto, N.; Chen, J. Effect of energy information provision on occupant’s behavior and energy consumption in public spaces. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Built Environment Conference 2019 Tokyo (SBE19Tokyo) Built Environment in an Era of Climate Change: How Can Cities and Buildings Adapt? Tokyo, Japan, 6–7 August 2019; 2019 IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; The University of Tokyo: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Volume 294, p. 012080. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.J.; Fu, H.; Wang, Y.R. The impact of the water commonweal propaganda on citizens’ water-saving behavior: The intermediary role of propaganda channels and forms–evidence from China. Water Policy 2021, 23, 1468–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.; Wang, Q. Factor analysis and policy simulation of domestic waste classification behavior based on a multiagent study—Taking Shanghai’s garbage classification as an example. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chen, W.; Ma, H.; Yang, H. Influence of Publicity and Education and Environmental Values on the Green Consumption Behavior of Urban Residents in Tibet. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Wang, J.P.; Zhao, S.L.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Richert, M.; Johnson, M.; Lundie, S. Climate inaction and managerial sensemaking: The case of renewable energy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2502–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y. How Does Policy Perception Affect Green Entrepreneurship Behavior? An Empirical Analysis from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 7973046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Li, Q.C.; Rentocchini, F.; Tamvada, J.P. Born to be green: New insights into the economics and management of green entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awaga, A.L.; Xu, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. Evolutionary game of green manufacturing mode of enterprises under the influence of government reward and punishment. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2020, 15, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.K.W.; Lee, S.H.N.; Jung, S. The Role of the Institutional Environment in the Relationship between CSR and Operational Performance: An Empirical Study in Korean Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Z.; Xu, S.; Shen, W.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Factors that influence corporate environmental behavior: Empirical analysis based on panel data in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, Ó. A study of determinant factors of stakeholder environmental pressure perceived by industrial companies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2010, 19, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Hwang, B.; Lu, Y. Exploring the Influencing Paths of Behavior-driven Household Energy-saving Intervention—Household Energy Saving Option (HESO). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shen, D.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Qu, X.; Tao, D. Predicting unsafe behaviors at nuclear power plants: An integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020, 80, 103047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucinhato, R.M.D.; da Cunha, D.T.; Barros, S.C.F.; Zanin, L.M.; Auad, L.I.; Weis, G.C.C.; Saccol, A.L.D.F.; Stedefeldt, E. Behavioral predictors of household food-safety practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Food Control 2022, 134, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tama, R.A.Z.; Ying, L.; Yu, M.; Hoque, M.M.; Adnan, K.M.; Sarker, S.A. Assessing farmers’ intention towards conservation agriculture by using the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Mangmeechai, A.; Su, J. Linking Perceived Policy Effectiveness and Proenvironmental Behavior: The Influence of Attitude, Implementation Intention, and Knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Gan, X.; Qiao, L. Promoting differentiated energy savings: Analysis of the psychological motivation of households with different energy consumption levels. Energy 2021, 218, 119563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ habitual energy-saving behaviour based on NAM and TPB models: Egoism or altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ho, Y. The Influences of Environmental Uncertainty on Corporate Green Behavior: An Empirical Study with Small and Medium-Size Enterprises. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2010, 38, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.-D.; Soebarto, V.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Zillante, G. Facilitating the transition to sustainable construction: China’s policies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Potocnik, K.; Jing, Z. Innovation and Creativity in Organizations A State-of-the-Science Review, Prospective Commentary, and Guiding Framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutzschbach, J.; Tanikulova, P.; Lueg, R. The Role of Top Managers in Implementing Corporate Sustainability—A Systematic Literature Review on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Yang, C.; Bossink, B.; Fu, J. Linking Leaders’ Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior and Team Green Innovation: The Mediation Role of Team Green Efficacy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.B.; Sun, H. Executives’ Environmental Awareness and Eco-Innovation: An Attention-Based View. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V.; Nedelko, Z.; Peleckienė, V.; Peleckis, K. Values, environmental concern and economic concern as predictors of enterprise environmental responsiveness. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NilsPlambeck. The development of new products: The role of firm context and managerial cognition. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Zuo, X.G.; Li, H.L. The dual effects of heterogeneous environmental regulation on the technological innovation of Chinese steel enterprises—Based on a high-dimensional fixed effects model. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 188, 107113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Fauzi, M.A. Environmental awareness and leadership commitment as determinants of IT professionals engagement in Green IT practices for environmental performance. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choon, S.W.; Ong, H.B.; Tan, S.H. Does risk perception limit the climate change mitigation behaviors? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1891–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Managerial Interpretations and Organizational Context as Predictors of Corporate Choice of Environmental Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damert, M.; Feng, Y.T.; Zhu, Q.H.; Baumgartner, R.J. Motivating low-carbon initiatives among suppliers: The role of risk and opportunity perception. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhou, R.; Anwar, M.A.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Asmi, F. Entrepreneurs and Environmental Sustainability in the Digital Era: Regional and Institutional Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sibian, A.; Ispas, A. An Approach to Applying the Ability-Motivation-Opportunity Theory to Identify the Driving Factors of Green Employee Behavior in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, T.; Chetty, S. Effectuation and Networking of Internationalizing SMEs. Manag. Int. Rev. 2015, 55, 647–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Angelika, P. Explaining consumers’ intentions towards purchasing green food in Qingdao, China: The amendment and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2019, 133, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Li, X.; Masanet, E.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Ries, R. Unlocking the green opportunity for prefabricated buildings and construction in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Harun, A.B.; Alam, M.N.; Karim, A.M.; Tabash, M.I.; Hossain, M.I.; Aziz, S.; Abbasi, B.A.; Ojuolape, M.A. Green product as a means of expressing green behaviour: A cross-cultural empirical evidence from Malaysia and Nigeria. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, C.; Arun, K. What color is the green entrepreneurship in Turkey? J. Entrepreneurship. Emerg. Econ. 2016, 8, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Kujinga, L. The institutional environment and social entrepreneurship intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhao, X.; Prahinski, C.; Li, Y. The impact of institutional pressures, top managers’ posture and reverse logistics on performance—Evidence from China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraporn, O.; Chalermporn, S. The Impact of Green Corporate Identity and Green Personal-Social Identification on Green Business Performance: A Case Study in Thailand. J. Asian Financ. Econ. 2021, 8, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, J.A.; Jia, J. Purchasing Green Products as a Means of Expressing Consumers’ Uniqueness: Empirical Evidence from Peru and Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perron, G.M.; Côté, R.P.; Duffy, J.F. Improving environmental awareness training in business. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Liu, H. Environmental, Social, Governance Activities and Firm Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An Empirical Study of Environmental Awareness and Practices in SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, B.L. Environmental investment decisions of family firms—An analysis of competitor and government influence. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Factors Impacting on Social and Corporate Governance and Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from Listed Vietnamese Enterprises. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Qin, S.; Gou, Z.; Yi, M. Can Green Building Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviours? The Psychological Model and Design Strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Price Competition and Clean Production in The Presence of Environmental Concerns. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2009, 8, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasford, J.; Farmer, A. Responsible you, despicable me: Contrasting competitor inferences from socially responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y. Green product pricing with non-green product reference. Transport. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 115, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. Transitioning to a Low-Carbon Economy: Green Financial Behavior, Climate Change Mitigation, and Environmental Energy Sustainability. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2021, 13, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. Leveraging Green Finance for Low-Carbon Energy, Sustainable Economic Development, and Climate Change Mitigation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Contemp. Philos. 2021, 20, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. Corporate Environmental Performance, Climate Change Mitigation, and Green Innovation Behavior in Sustainable Finance. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 3, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Grilli, L.; Mrkajic, B. The role of institutional pressures in the introduction of energy-efficiency innovations. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mller, J.; Herm, S. Perceptions of Green User Entrepreneurs’ Performance—Is Sustainability an Asset or a Liability for Innovators? Sustainability 2021, 13, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Lu, Y. Stakeholder pressure, corporate environmental ethics and green innovation. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2021, 29, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Feng, T.; Xin, X.; Hao, G. How to respond to competitors’ green success for improving performance: The moderating role of organizational ambidexterity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental Strategy, Institutional Force, and Innovation Capability: A Managerial Cognition Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xu, S.; Shen, W.; Wang, M.; Li, C. Exploring external and internal pressures on the environmental behavior of paper enterprises in China: A qualitative study. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 951–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X.; Yan, L. How to drive green innovation in China’s mining enterprises? Under the perspective of environmental legitimacy and green absorptive capacity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Qi, Y. Why Do Firms Obey? The State of Regulatory Compliance Research in China. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2020, 25, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Henan Statistical Yearbook 2021. 2022. Available online: http://www.henan.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/tjxx/tjnj/ (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Majid, A.R.; Elhadj, B. Determining the enabling factors for implementing cloud data governance in the Saudi public sector by structural equation modelling. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 107, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tang, J. Stakeholder–firm power difference, stakeholders’ CSR orientation, and SMEs’ environmental performance in China. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; Whybark, D.C. The Impact of Environmental Technologies on Manufacturing Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y. Environmental regulation and green innovation: Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, T.; Engel, S.; Kammerer, D.; Seijas, J.; Zurich, E.T.H. Explaining Green Innovation: Ten Years after Porter’s Win-Win Proposition: How to Study the Effects of Regulation on Corporate Environmental Innovation? Politische Vierteljahresschr. 2007, 39, 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.L.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Zhang, S.F. Corporate behavior and competitiveness: Impact of environmental regulation on Chinese firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, G. The influence of green technology cognition in adoption behavior: On the consideration of green innovation policy perception’s moderating effect. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2017, 20, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, H. An empirical examination of individual green policy perception and green behaviors. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B.; Petrovits, C.; Radhakrishnan, S. Is Doing Good Good for You? How Corporate Charitable Contributions Enhance Revenue Growth. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Luis, R.G.M. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. The Influence of Corporate Environmental Ethics on Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Role of Green Innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bai, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, J. Incentives for Green and Low-Carbon Technological Innovation of Enterprises under Environmental Regulation: From the Perspective of Evolutionary Game. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 793667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.; Penn, J. The impact of information-based interventions on conservation behavior: A meta-analysis. Resour. Energy Econ. 2020, 62, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Cheng, Y. The Influence of Norm Perception on Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison between the Moderating Roles of Traditional Media and Social Media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L.; Tan, L.P. Exploring the Gap Between Consumers’ Green Rhetoric and Purchasing Behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item | Count | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 139 | 69.85 |

| Female | 60 | 30.15 | |

| Age | ≤30 | 114 | 57.29 |

| 31–40 | 55 | 27.64 | |

| 41–50 | 22 | 11.06 | |

| >50 | 8 | 4.02 | |

| Length of service | <5 | 74 | 37.19 |

| 5–10 | 94 | 47.24 | |

| 11–20 | 27 | 13.57 | |

| >20 | 4 | 2.01 | |

| Education background | College Degree or below | 46 | 23.12 |

| Bachelor Degree | 116 | 58.29 | |

| Master Degree | 33 | 16.58 | |

| Doctoral Degree | 4 | 2.01 | |

| Corporate scale | corporations above designated scale | 57 | 28.64 |

| corporations below designated scale | 142 | 71.36 | |

| Corporate ownership | State-owned enterprise (SOE) | 116 | 58.29 |

| Non-state-owned enterprise (non-SOE) | 83 | 41.71 |

| Question Items | Average | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Xuanguan | ||

| Actively promote sustainable development | 3.72 | 1.11 |

| Provides green information related to our corporation | 3.60 | 1.02 |

| The information is very sufficient | 3.66 | 0.92 |

| PG Opportunity | ||

| Green behavior can improve corporate economic performance | 3.53 | 1.10 |

| Green behavior can improve corporate environmental performance | 3.75 | 1.05 |

| Green behavior can improve corporate production efficiency | 3.63. | 0.94. |

| Green behavior can enhance corporate image | 3.84 | 1.05 |

| Green behavior can enhance the corporate comprehensive competitiveness | 3.76 | 1.03 |

| PG Risk | ||

| Fully understand the adverse impact of the corporation on the environment | 3.58 | 1.11 |

| Fully understand the impact of environmental regulations on the corporation | 3.65 | 1.09 |

| Fully understand the best environmental protection measures in the industry | 3.71 | 1.02 |

| Think it is right to assume social responsibility for environmental protection | 3.77 | 1.02 |

| PGI of Competitor | ||

| Attach great importance to environmental protection in operation | 3.70 | 1.14 |

| Think green behavior is very important to the whole society | 3.77 | 1.07 |

| Take green behavior as an important index to evaluate the corporate reputation | 3.69 | 0.93 |

| Pay close attention to the environmental protection behavior of our corporation | 3.72 | 1.12 |

| PGI of Territorial Government | ||

| Take environmental protection as one of the important tasks of governance | 3.75 | 1.16 |

| Think green behavior is very important to the whole society | 3.73 | 1.07 |

| Take green behavior as an important index to evaluate the corporate reputation | 3.74 | 1.04 |

| Pay close attention to the environmental protection behavior of our corporation | 3.81 | 1.00 |

| GTI | ||

| Willing to increase investment in the innovative design of green products | 3.79 | 1.13 |

| Pay attention to the transformation of R & D focus to green products | 3.75 | 1.08 |

| Committed to improving production processes to reduce pollution and consumption | 3.78 | 1.06 |

| Prefer to design new products with low pollution and low energy consumption | 3.79 | 1.06 |

| Prefer to design new products with low pollution and low energy consumption | 3.81. | 1.02 |

| GPP | ||

| Compared with peers, the equipment used is greener and more advanced | 3.72 | 0.96 |

| Compared with peers, the process technology used is greener and energy-saving | 3.72 | 0.96 |

| Compared with peers, the raw materials used are more environmentally friendly | 3.72 | 0.96 |

| Compared with its peers, a higher proportion of green and clean energy are used | 3.75 | 0.98 |

| Compared with peers, treatment or recycling are paid more attention | 3.73 | 0.97 |

| GM | ||

| Compared with peers, identify the green needs of customers more efficiently | 3.67 | 1.07 |

| Compared with peers, pay attention to the green behavior of channel members | 3.73 | 0.93 |

| Compared with peers, the promotion process thinks highly of environmental protection | 3.75 | 0.97 |

| Compared with peers, prefer to implement green communication | 3.73 | 0.92 |

| Compared with peers, more inclined to establish a green corporate image | 3.88 | 0.99 |

| When formulating strategies, more consideration is given to environmental protection | 3.73 | 1.03 |

| Will adjust the organizational structure to implement green behavior | 3.76 | 0.95 |

| GER | ||

| The environmental laws and regulations faced are relatively perfect | 3.69 | 1.14 |

| Strict environmental protection laws and regulations are faced | 3.68 | 1.04 |

| If it fails to meet the environmental standards, it will be subject to strict pollution control punishment | 3.78 | 1.05 |

| The government has formulated a perfect tax preference system for corporate green behavior | 3.66 | 0.99 |

| The government provides well-established project loan discounts or loan preferences for corporations implementing green behavior | 3.69 | 1.07 |

| The government provides special fund subsidies with a perfect system for corporate green projects | 3.75 | 1.10 |

| Latent Variable | Indicators | Alpha | KMO | Bartlett | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuanguan | 3 | 0.883 | 0.806 | 0.000 | 0.699 | 0.874 |

| PG Opportunity | 5 | 0.868 | 0.884 | 0.000 | 0.648 | 0.902 |

| PG Risk | 4 | 0.901 | 0.823 | 0.000 | 0.623 | 0.869 |

| PGI of competitor | 4 | 0.880 | 0.837 | 0.000 | 0.650 | 0.881 |

| PGI of territorial government | 4 | 0.892 | 0.839 | 0.000 | 0.677 | 0.893 |

| GTI | 5 | 0.905 | 0.893 | 0.000 | 0.658 | 0.906 |

| GPP | 5 | 0.860 | 0.858 | 0.000 | 0.553 | 0.861 |

| GM | 7 | 0.893 | 0.907 | 0.000 | 0.544 | 0.893 |

| GER | 6 | 0.924 | 0.909 | 0.000 | 0.670 | 0.924 |

| Index | CMIN/DF | NFI | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model results | 1.758 | 0.804 | 0.062 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.897 |

| Standard | <3 | >0.5 | <1 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.8 |

| Model accuracy | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| Index | CMIN/DF | NFI | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model results | 1.708 | 0.799 | 0.060 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 0.898 |

| Standard | <3 | >0.5 | <1 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.8 |

| Model accuracy | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| Model | UnStd.C | High Score (p) | Medium Score (p) | Low Score (p) | F | R-sq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.1957 *** | *** | *** | *** | 13.7758 | 0.0399 |

| Model 2 | 0.2173 *** | 0.2972 | *** | *** | 11.4537 | 0.0472 |

| Model 3 | 0.1426 ** | 0.0379 ** | *** | *** | 5.0862 | 0.0189 |

| Model 4 | 0.1243 ** | 0.0343 ** | *** | *** | 4.0097 | 0.0150 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Ma, L. Does Government-Led Publicity Enhance Corporate Green Behavior? Empirical Evidence from Green Xuanguan in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063181

Wu Y, Zhang J, Liu S, Ma L. Does Government-Led Publicity Enhance Corporate Green Behavior? Empirical Evidence from Green Xuanguan in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063181

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yuan, Jin Zhang, Shoulin Liu, and Lianrui Ma. 2022. "Does Government-Led Publicity Enhance Corporate Green Behavior? Empirical Evidence from Green Xuanguan in China" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063181