The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- How does the success factor of K-pop affect SNS citizenship behavior?

- RQ2:

- How does national image affect SNS citizenship behavior and tourist behavioral intention?

- RQ3:

- How does SNS citizenship behavior affect tourist behavioral intention?

- RQ4:

- Is there a mediating effect of national image and SNS citizenship behavior in the relationship between the success factors of K-pop and tourist behavioral intention?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Base Theories

2.2. Service Quality Model

2.3. Image Theory

- (1)

- The value image is the decision-maker’s principle, and it contains the concepts that define what is right, such as beliefs, values, moral standards, ethics, and norms. For example, “Let’s fulfill the social responsibility” is a value image (value/standard/principle). Such a principle works as a criterion for judging the appropriateness of the decision making with regard to designing and choosing the alternative goals and plans that are likely to be selected [59,60].

- (2)

- (3)

- The strategic image comprises different plans selected for achieving a goal, a strategy for achieving the plan, and a prediction of the outcome of the strategy. Planning is an abstract process that entails a series of behaviors ranging from goal setting to goal achievement. Strategy refers to the specific and practical behaviors required by the plan. Prediction means forecasting future outcomes that will take place upon selecting a certain plan and strategy [59,60]. This entails planning/implementation/enforcement of actions.

2.4. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.5. Success Factors of K-Pop

2.6. National Image

2.7. SNS Citizenship Behavior

2.8. Tourist Behavioral Intention

2.9. Relationship between Key Variables

2.10. Hypotheses

3. Methods

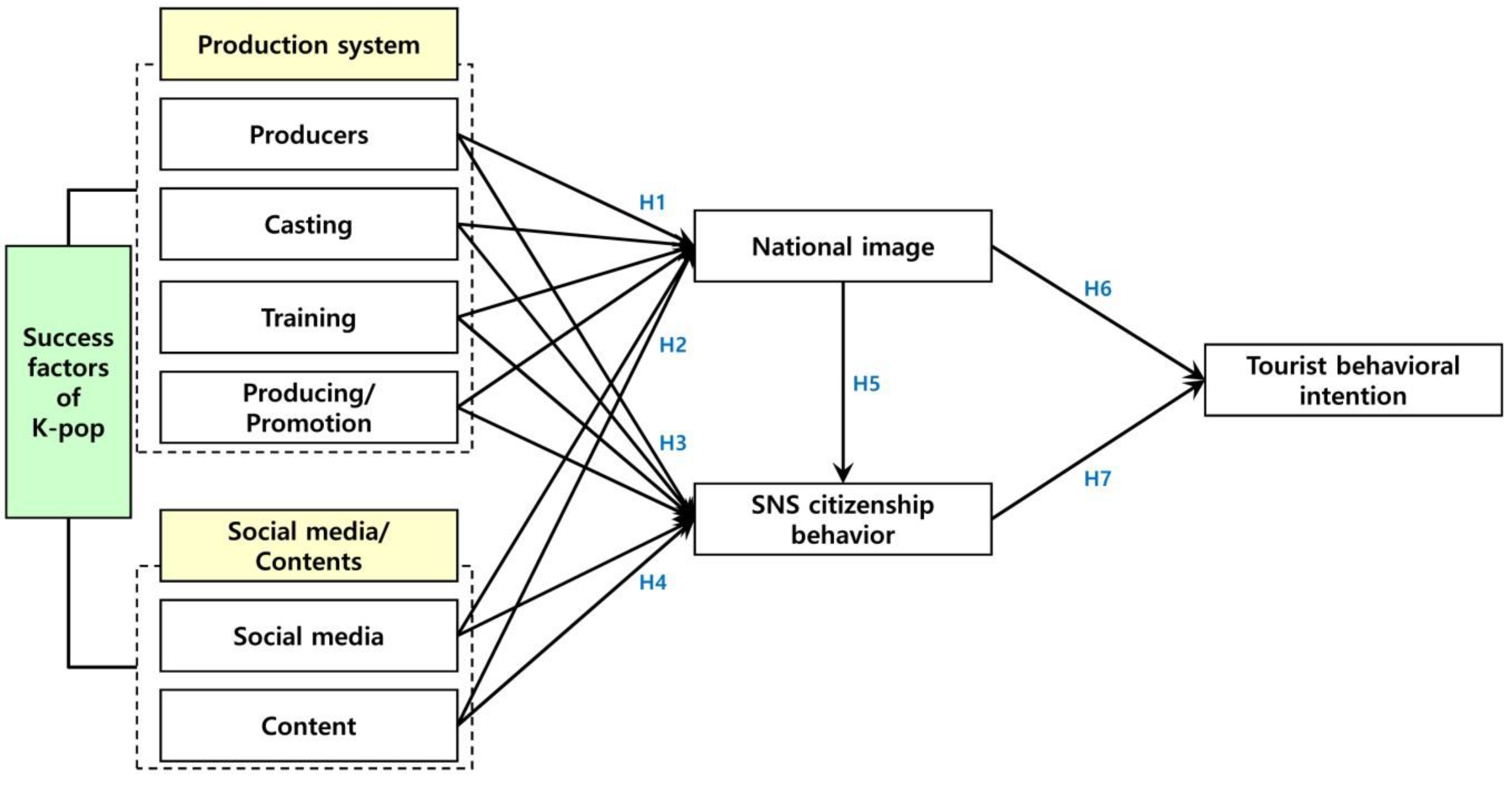

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Variable Measurements

3.3. Respondents

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.5. The Mediated Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of the Study

5.2. Implications of this Study

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryu, J.; Capistrano, E.P.; Lin, H.C. Non-Korean consumers’ preferences on Korean popular music: A two-country study. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 62, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, B. Cultural amnesia or continuity? Expressions of han in K-pop. East Asian J. Pop. Cult. 2020, 6, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.J. Blackpink queers your area: The global queerbaiting and queer fandom of K-pop female idols. Fem. Media Stud. 2021, 21, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanozia, R.; Ganghariya, G. More than K-pop fans: BTS fandom and activism amid COVID-19 outbreak. Media Asia 2021, 48, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parc, J.; Kim, S.D. The digital transformation of the Korean music industry and the global emergence of K-pop. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.I. 14. How K-pop went global: Digitization and the market-making of Korean entertainment houses. In Pop Empires: Transnational and Diasporic Flows of India and Korea; Heijin Lee, S., Mehta, M., Ji-Song Ku, R., Alexy, A., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2019; pp. 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.; Haidar, S. Online community development through social interaction—K-Pop stan twitter as a community of practice. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K. Diasporic youth culture of K-pop. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 22, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, J. Factors influencing K-pop artists’ success on V live online video platform. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.Y. Transnationalism, cultural flows, and the rise of the Korean Wave around the globe. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2019, 81, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, B. K-Pop strategy seen from the viewpoint of cultural hybridity and the tradition of the Gwangdae. Kritika Kultura 2017, 29, 292–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bang, Y.Y.; Joo, Y.; Seok, H.; Nam, Y. Does K-pop affect Peruvians’ Korean images and visit intention to Korea? Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3519–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.M. Rediscovering the idols: K-pop idols behind the mask. Celebrity Stud. 2017, 8, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y. Performed intermediality and beyond in the BTS music video ‘Idol’: K-Pop idol identities in contemporary Hallyu. East Asian J. Pop. Cult. 2020, 6, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K. Success factor analysis of new Korean wave ‘K-POP’ and a study on the importance of smart media to sustain Korean wave. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerlin, P.A.; Shin, W. The success of K-pop: How big and why so fast? Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 45, 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, M.H.; Choi, H.J. Popular culture influences on national image and tourism behavioural intention: An exploratory study. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, E. How “smart” are K-pop fans: Can the study of emotional intelligence of K-pop fans increase marketing potential. Cult. Empathy 2019, 2, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, N.G.; Hidayat, Z. Influencing factors in fans’ consumer behavior: BTS meal distribution in Indonesia. J. Distrib. Sci. 2021, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.G.B.; Seo, Y.; Binay, I. Cultural globalization from the periphery: Translation practices of English-speaking K-pop fans. J. Consum. Cult. 2021, 21, 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, A.L. Transnational identities and feeling in fandom: Place and embodiment in K-pop fan reaction videos. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2018, 11, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H. English and K-pop: The case of BTS 1. In English in East and South Asia: Policy, Features and Language in Use; Low, E.L., Pakir, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K. Global imagination of K-pop: Pop music fans’ lived experiences of cultural hybridity. Pop. Music Soc. 2018, 41, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. The rise of Time Fengjun Entertainment. SSR 2021, 3, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Jesus, C.F. “BangBangCon: The live”—A case study on live performances and marketing strategies with the Korean-Pop group “BTS” during the pandemic scenario in 2020. AMJ 2021, 22, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Kim, B. The “Hallyu” phenomenon: Utilizing tourism destination as product placement in K-POP culture. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, J.E.; Choi, H.J. Korean dance performance influences on prospective tourist cultural products consumption and behaviour intention. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, J.H. Brand loyalty and the Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS) Korean dance: Global viewers’ perceptions. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.K. A Study on the Factors of Overseas Spread of K-pop: With Focus on the Analysis of Producer, Recipient, Media and Content Field. Ph.D. Thesis, Kookmin University Graduate, Seoul, Korea, 2019. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T15372345 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Kim, H.S. A Study on Success Strategies for Global Marketing of K-Pop: Focusing on Experts' In-Depth Interview. Master's Thesis, The Graduate School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 2012. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T12865319 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Lie, J. What is the K in K-pop? South Korean popular music, the culture industry, and national identity. Korea Obs. 2012, 43, 339–363. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.M.; Lee, S.B. The knowledge structure of K-pop research in Korea: Focusing on the network analysis of research keyword 2012–2021. J. Media Econ. Cult. 2021, 19, 7–38. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A107932359 (accessed on 22 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Cui, L.; Zeng, G.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Yan, S.; Yan, B. Applying the fuzzy SERVQUAL method to measure the service quality in certification & inspection industry. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2015, 26, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C. The influence of e-banking service quality on customer loyalty: A moderated mediation approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenkov, G.; Dika, Z. A sustainable e-service quality model. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 414–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkisz, A.; Karniej, P.; Krasowska, D. SERVQUAL method as an “Old New” tool for improving the quality of medical services: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladhari, R. A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2009, 1, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.L.; Barkur, G.; Varambally, K.V.M.; Motlagh, F.G. Comparison of SERVQUAL and SERVPERF metrics: An empirical study. TQM J. 2011, 23, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Kothadiya, O.; Tavasszy, L.; Kroesen, M. Quality assessment of airline baggage handling systems using SERVQUAL and BWM. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.T.; Syed, Z.; Imam, A.; Raza, A. The impact of airline service quality on passengers’ behavioral intentions using passenger satisfaction as a mediator. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 85, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Basu, A.; Ware, N. Quality measurement of Indian commercial hospitals—Using a SERVQUAL framework. BIJ 2018, 25, 815–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, E.K. The effects of Korean medical service quality and satisfaction on revisit intention of the United Arab Emirates government sponsored patients. Asian Nurs. Res. 2017, 11, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Famiyeh, S.; Kwarteng, A.; Asante-Darko, D. Service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty in automobile maintenance services: Evidence from a developing country. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2018, 24, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Singh, A.K.; Kaushik, K. Evaluating service quality in automobile maintenance and repair industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.T.; James, J. Service quality evaluation of automobile garages using a structural approach. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2021, 38, 602–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdyev, S.; Ihtiyar, A.; Banaitis, A.; Thurnell, D. The construction client satisfaction model: A PLS-SEM approach. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Phadtare, M. Service quality for architects: Scale development and validation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour Soleimani, A.; Einolahzadeh, H. The influence of service quality on revisit intention: The mediating role of WOM and satisfaction (Case study: Guilan travel agencies). Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1560651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtasham, S.S.; Sarollahi, S.K.; Hamirazavi, D. The effect of service quality and innovation on word of mouth marketing success. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2017, 7, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. A preliminary study of job performance in entertainment management using DACUM job analysis. J. Secr. Stud. 2010, 19, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.H.; Park, J.H. Policy measures: Strengthening K-pop competitiveness. Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade. Policy Data 2017, 239, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K. A study on the structure and the characteristic of the relation in the entertainment industry. Hum. Contents 2012, 26, 73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, L.R.; Mitchell, T.R. Image theory: Principles, goals, and plans in decision making. Acta Psychol. 1987, 66, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, C.; Vardaman, J.; Marler, L.; Antin-Yates, V. An image theory of strategic decision-making in family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2019, 9, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavou, H.; Lioukas, S. An empirical juxtapose of the effects of self-image on entrepreneurial career along the spectrum of nascent to actual entrepreneurs. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, L.R.; Puto, C.P.; Heckler, S.E.; Naylor, G.; Marble, T.A. Differential versus unit weighting of violations, framing, and the role of probability in image theory’s compatibility test. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 65, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.A. Consumer decision making and image theory: Understanding value-laden decisions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.N.; Dahling, J.J. Image theory and career aspirations: Indirect and interactive effects of status-related variables. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G. Gender/sexuality politics of Korean entertainment industry structured by entertainment management companies. J. Korean Women Stud. 2014, 30, 53–88. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.H.; Jeong, C. An exploratory study on the sustainability of Korean wave and successful process of Korean cultural wave contents: A case of PSY’s GangNam style. J. Tour. Sci. 2014, 38, 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, B.C.; Sim, H. Sucess factor analysis of K-POP and a study on sustainable Korean wave—Focus on smart media based on realistic contents. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, I.K.; Kim, J.B.; Oh, J.W. A study on the “Korean drama and movie wave” in China and Japan. J. Kor. Serv. Manag. Soc. 2007, 8, 155–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Cha, H.W. How Korean popular music(K-Pop)’s cultural proximity influences oversea audience’s evaluation of K-Pop’s image and South Korea’s national image. J. Commun. Stud. 2015, 59, 267–300. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, I.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, S.H.; An, B.J.; Kim, J.H. Quality of Olympics opening ceremony: Tourism behavioural intention of international spectators. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.T.; Seok, B.I.; Choi, H.J.; Jung, S.H. Competitive factors of electronic dance music festivals with Social Networking Service (SNS) citizenship behaviour of international tourists. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.Y.; Jung, S.H.; Yu, J.P.; Bae, K.H.; An, B.J.; Kim, J.H. Perceived tourist values of the Museum of African Art. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, A.; Brønn, P.S. Applying Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior to predict practitioners’ intentions to measure and evaluate communication outcomes. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Z.D. The enduring use of the theory of planned behavior. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2017, 22, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Jensen, J.M.; Solgaard, H.S. Predicting online grocery buying intention: A comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2004, 24, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, L.; Angus, D.J.; Blaszczynski, A.; Gainsbury, S.M. Understanding use of consumer protection tools among Internet gambling customers: Utility of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action. Addict. Behav. 2019, 99, 106050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzer, M. Theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; Rossler, P., Hoffner, C.A., Zoonen, L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishoy, G.A. The theory of planned behavior and policing: How attitudes about behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control affect the discretionary enforcement decisions of police officers. Crim. Justice Stud. 2016, 29, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, H.; Davidov, E.; Schmidt, P. Three approaches to estimate latent interaction effects: Intention and perceived behavioral control in the theory of planned behavior. Methodol. Innov. Online 2011, 6, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuhr, M. Globalization and Popular Music in South Korea: Sounding Out K-Pop; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.W. Unveiling the success factors of BTS: A mixed-methods approach. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 1518–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I. The globalization of K-pop: Korea’s place in the global music industry. Korea Obs. 2013, 44, 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.I.; Kim, L. Organizing K-pop: Emergence and market making of large Korean entertainment houses, 1980–2010. East Asia 2013, 30, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.Y. New wave formations: K-pop idols, social media, and the remaking of the Korean wave. In Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media; Lee, S., Nornes, A.M., Eds.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S. K-pop, Indonesian fandom, and social media. Transform. Works Cult. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Youth, social media and transnational cultural distribution: The case of online K-pop circulation. In Mediated Youth Cultures; Bennett, A., Robards, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, V.; Balica, E. Korean cultural products in Eastern Europe: A case study of the K-Pop impact in Romania. Region 2013, 2, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Jin, D.Y.; Han, B. Transcultural fandom of the Korean wave in Latin America: Through the lens of cultural intimacy and affinity space. Media Cult. Soc. 2019, 41, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.Y. K-pop reception and participatory fan culture in Austria. Cross-Currents 2014, 3, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doré, P.; Pugsley, P.C. Genre conventions in K-pop: BTS’s ‘Dope’ music video. Continuum 2019, 33, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.; Lee, H.J. K-pop in Korea: How the pop music industry is changing a post-developmental society. Cross-Currents 2014, 3, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parc, J.; Messerlin, P.; Moon, H.C. The secret to the success of K-pop: The benefits of well-balanced copyrights. In Corporate Espionage, Geopolitics, and Diplomacy Issues in International Business; Christiansen, B., Kasarcpolit, Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 130–148. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Papadopoulos, N.; Heslop, L.A.; Mourali, M. The influence of country image structure on consumer evaluations of foreign products. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Han, H. Effects of TV drama celebrities on national image and behavioral intention. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, K.; Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M. Globalization, national identity, biculturalism and consumer behavior: A longitudinal study of Dutch consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.L. Brands and national image: An exploration of inverse country-of-origin effect. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2012, 8, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeugner-Roth, K.P.; Žabkar, V.; Diamantopoulos, A. Consumer ethnocentrism, national identity, and consumer cosmopolitanism as drivers of consumer behavior: A social identity theory perspective. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.Y.; Jo, S.C. The influence of Korea’s national image on intention to use Korean wave contents and mediating effect of the Korean wave fandom identification: Focusing on Asian consumers. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q. Relationship among China’s country image, corporate image and brand image: A Korean consumer perspective. J. Contemp. Mark. Sci. 2019, 2, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.M.; Zeugner-Roth, K.P. Disentangling country-of-origin effects: The interplay of product ethnicity, national identity, and consumer ethnocentrism. Mark. Lett. 2017, 28, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Seok, B.I.; Lee, K.T.; Yu, J.P. Effects of social responsibility activities of franchise chain hotels on customer value and SNS citizenship behavior. Korean J. Franch. Manag. 2017, 8, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J. Effect of chief executive officer’s sustainable leadership styles on organization members’ psychological well-being and organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.W. Examining the impact of online friendship desire on citizenship behavior. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 23, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.A.; Zhang, P.; DiPietro, R.B.; Meng, F. Food tourist segmentation: Attitude, behavioral intentions and travel planning behavior based on food involvement and motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, M.; Xie, K.L. Chinese travelers’ behavioral intentions toward room-sharing platforms: The influence of motivations, perceived trust, and past experience. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2688–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.H.; Yang, J.Y. The effects of Korean wave contents on country image and behavioral intentions. Korea J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 25, 1917–1938. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H. A study on Korea country image and cosmetics brand image in Vietnam market by the Korean wave. Int. Commer. Inf. Rev. 2015, 17, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S. Brand management process for national brand image. J. Korea Soc. Des. Sci. 2009, 22, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.M.; Chen, X.; Rhee, S.Y. The Korean wave in China and perceived images of Korean brands: Korean wave advertising vs. country-of-origin effects. Korean Manag. Rev. 2011, 40, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.Y. Convergence of the image of the professor in human resources of small and medium enterprises to self image: Mediating effect of voice image. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2017, 7, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Jung, J.W. National brand image strategy through BPL cultural marketing: Focused on BPL promotional advertisements. KDK J. 2012, 24, 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Park, S.T. A study on the effect of social media on country image and purchasing intention: Focused on Chinese consumers. J. Digit. Converg. 2012, 10, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.J.; Park, S.H. A study the relation between popular factors and likability of hallyu and the national image. J. Public Relat. 2012, 16, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadzayo, M.W.; Matanda, M.J.; Ewing, M.T. The impact of franchisor support, brand commitment, brand citizenship behavior, and franchisee experience on franchisee-perceived brand image. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1886–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.T. How does service climate influence hotel employees’ brand citizenship behavior? A social exchange and social identity perspective. Australas. Mark. J. 2022, 30, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.H.; Park, B.G. The effects of corporate social responsibility on company image and customer citizenship behavior: Focused on Japanese students. J. Digit. Converg. 2019, 17, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Campo, S. The influence of political conflicts on country image and intention to visit: A study of Israel’s image. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.P.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, M.S. Effects of Korean wave image influences on the purchase intention of Korean educational product—Focus on the controlling effects of engagement in Chinese university students. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.H.; Kwon, J.H.; Bae, K.H. Impact of K-pop consumption attributes on national image and behavioral intention to visit: Targeting Americans, British, South Africans and Filipinos. J. Korea Cult. Ind. 2018, 18, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K.; Kim, G.D.; Choi, H.J. The effects of Hanllu on national image, Korea and wedding tourism. Northeast Asian Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Kim, C.S. The effect of country image on tourist destination attitudes and behavioral intentions. J. Tour. Sci. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Lockshin, L. Halo effects of tourists’ destination image on domestic product perceptions. Australas. Mark. J. 2011, 19, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Cha, S.M. Effects of restaurant customer’s participation and citizenship behavior on satisfaction, commitment and revisit intention. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2017, 29, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.Y.; Song, M.G. The effects of community attachment and civic consciousness on pro-environmental behavioral intention: Pyeongtaek Case Study. J. Environ. Policy Adm. 2017, 25, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A.C. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G.; Choi, J.Y. An empirical comparison of generalized structured component analysis and partial least squares path modeling under variance-based structural equation models. Behaviormetrika 2020, 47, 243–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Takane, Y. Generalized structured component analysis. Psychometrika 2004, 69, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. Performing arts and sustainable consumption: Influences of consumer perceived value on ballet performance audience loyalty. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.N.; Lee, H.W.; Choi, H.J. Brand personality of Korean dance and sustainable behavioral intention of global consumers in four countries: Focusing on the technological acceptance model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.J.; Choi, H.J.; Seok, B.I.; Lee, N.H. Effects of social network services (SNS) subjective norms on SNS addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Ahn, J.C.; Kim, B.S.; Choi, H.J. Social networking sites self-image antecedents of social networking site addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Ahn, J.C.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Communities of practice and knowledge management systems: Effects on knowledge management activities and innovation performance. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2020, 18, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, J. Antecedent factors that affect restaurant brand trust and brand loyalty: Focusing on US and Korean consumers. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2021, 30, 990–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Service Field | Tangibility | Reliability | Responsiveness | Assurance | Empathy | Researcher (Source) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airlines | Airplanes, ticketing counters, uniforms | Departing and arriving on time | Swiftness in baggage handling and ticketing, and promptness upon request for inflight service | Trustable names, safety records, competent employees | Understanding and caring for individuals’ particular needs | Rezaei et al. [40] Shah et al. [41] |

| Medical service | Buildings, waiting rooms, examination rooms, medical equipment | Seeing patients at the scheduled time, giving accurate diagnosis | Attitude of carefully listening to customers (patients), short wait time | Expertise and skills, validated qualifications, fame and reputation | Treating patients with respect and care, remembering previous health problems | Ali et al. [42] Lee & Kim [43] |

| Auto repair | Repair facilities, waiting rooms, uniforms, repair equipment | Fixing the problem and getting it done within a promised time frame | Accessibility, short wait time, prompt response to requests | Mechanics with expert knowledge | Remembering the customer’s names, previous issues, and understanding preferences | Famiyeh et al. [44] Jain et al. [45] James & James [46] |

| Construction | Office, business proposal, invoice, employee attire | Proposing and executing the plans within budget | Responding quickly and accommodating the changes in needs in the construction process | Validated qualifications, reputation, expertise, and skills | Understanding the customer and the specific needs of the customer | Durdyev et al. [47] Prakash & Phadtare [48] |

| Travel agency | Office, travel agency website | Making proposals and reservations tailored to customer’s needs and budgets | Travel-related product reservation, visa processing | Finding and recommending local tourist destinations | Understanding and considering various situations (e.g., family trip, business trip, friendship) | Gholipour Soleimani & Einolahzadeh [49] Mohtasham et al. [50] |

| K-pop | Discovering talent through street auditions, events, and festivals (casting) | Producing albums and music videos with perfection/reliability for the global market (producing/promotion) | Real-time delivery or prompt communication with fans regarding assorted information about K-pop through SNS (social media) | Well-organized process and system related to K-pop production(producer), and professional trainings for talented trainees with the ability to convey confidence (training) | Optimizing a variety of contents and obtaining popularity and empathy (contents) | Chang [51] Choi & Park [52] Kim [53] Oh & Lee [33] |

| Image | Variables | Description | Researcher (Source) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value image | Producers |

| value/standard/principle | Chang [51] Choi & Park [52] Kim [53] |

| Casting |

| value/standard/principle | Chang [51] Choi & Park [52] Kim [53] Kim [61] | |

| Training |

| value/standard/principle | Chang [51] | |

| Producing/ promotion |

| value/standard/principle | Chang [51] | |

| Social media |

| value/standard/principle | An & Jeong [62] Chang [51] Cho & Sim [63] | |

| Contents |

| value/standard/principle | Chang [51] Lee, Kim, & Oh [64] Wen & Cha [65] | |

| ↓ | ||||

| Trajectory image | National image |

| goal agenda | Choi et al. [66] |

| SNS citizenship behavior |

| goal agenda | Kim et al. [67] | |

| ↓ | ||||

| Strategic image | Tourist behavioral intention |

| planning/implementation/enforcement | Choi et al. [66] Kwak et al. [28] Meng et al. [68] |

| Categorization and Classification | Variables | Description | Researcher (Source) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production system | Producers |

| Fuhr [78] Lee et al. [79] Oh [80] Shin & Kim [81] |

| Casting |

| Shin & Kim [81] | |

| Training |

| Oh [80] | |

| Producing/ Promotion | Producing factors:

| Fuhr [78] Lee et al. [79] | |

Promotion factors:

| Fuhr [78] Lee et al. [79] | ||

| Social media/contents | Social media |

| Jung [82] Jung [83] Jung [84] Marinescu & Balica [85] Min et al. [86] Sung [87] |

| Contents |

| Doré & Pugsley [88] Kim [14] Oh & Lee [89] Parc, Messerlin, & Moon [90] |

| Variables | Path | Variables | Description | Researcher (Source) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success factors of K-pop | → | National image |

| Suh & Yang [106] |

| Lee [107] | |||

| Wen & Cha [65] | |||

| Kim [108] | |||

| Han, Chen, & Rhee [109] | |||

| Kim [110] | |||

| Jang & Jung [111] | |||

| Li & Park [112] | |||

| Moon & Park [113] | |||

| Success factors of K-pop | → | SNS citizenship behavior |

| Kim [31] |

| Jun [30] | |||

| National image | → | SNS citizenship behavior |

| Nyadzayo, Matanda, & Ewing [114] Hoang [115] |

| Ahn & Park [116] | |||

| National image | → | Tourist behavioral intention |

| Alvarez & Campo [117] Kim, Kim, & Lee [118] Kim, Kwon, & Bae [119] Suh & Yang (2012) [106] |

| Kim, Kim, & Choi [120] Lee & Kim [121] Lee & Lockshin [122] | |||

| SNS citizenship behavior | → | Tourist behavioral intention |

| Kim, Kim, & Cha [123] |

| Kwon & Song [124] |

| Variables | Operational Definition | Measurement Item | Researcher (Source) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production system | Producers | Degree of systematic processes and systematization related to K-pop production | 1. Systematization of production process | Chang [51] Choi & Park [52] Kim [53] |

| 2. Preparation to enter the overseas market from a long-term perspective | ||||

| 3. Honing of skills from the planning stage to target the global market | ||||

| 4. Systematization of the entire production process forming promotion | ||||

| Casting | Degree of various efforts to discover K-pop talent | 1. Focus of efforts on talent discovery | Chang [51] Choi & Park [52] Kim [53] Kim [61] | |

| 2. Selection of trainees through various channels, including official auditions and the recommendations of acquainted celebrities | ||||

| 3. Prioritization of talent and hidden potential in evaluations | ||||

| 4. Active discovery of overseas talent through global auditions | ||||

| Training | Degree of comprehensive training to develop K-pop talent | 1. Korean agencies performing the role of powerful gatekeepers | Chang [51] | |

| 2. Dedicated teams of experts in Korea providing training focused on singing, dancing, English, etc. | ||||

| 3. Harsh training of trainees in a continuous survival style | ||||

| 4. Assigning roles such as singing, acting, and choreography based on the members’ strongest talents and combining them to create the best synergy | ||||

| Producing/promotion | Degree of production of high-quality albums and wide promotions suited for the global market in relation to K-pop | 1. Maximizing the quality of K-pop albums by involving the world’s premier experts in each creative field | Chang [51] | |

| 2. Overcoming cultural barriers in a short time period by releasing albums specialized for local markets | ||||

| 3. Optimizing lyrics, music videos, fashion, etc., for local cultures in album production | ||||

| 4. Wide utilization of K-pop recorded in the local language for local dramas, movies, commercials, etc. | ||||

| Social media/contents | Social media | Degree to which real-time information on various K-pop contents is provided or communicated through SNS | 1. Use of social media such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter | An & Jeong [62] Chang [51] Cho & Sim [63] |

| 2. Effectively leveraging the infectious nature of social media that enables quick word-of-mouth for overseas expansion | ||||

| 3. Effectively sharing news about performances and recent updates through social media | ||||

| 4. Expanding emotional interactions by directly communicating with overseas fans via social media | ||||

| Contents | Degree of additional originality and efforts to secure popular appeal after optimizing a variety of K-pop contents | 1. Fusion of Western pop styles with easy melodies that suit Eastern sentiments | Chang [51] Lee, Kim, & Oh [64] Wen & Cha [65] | |

| 2. Securing universal mass appeal to gain popularity across nationalities | ||||

| 3. Providing showy spectacles through highly synchronized choreography and point dances | ||||

| 4. Constantly varying sensuous fashions and styles whenever a new song is released | ||||

| National image | Level of economic and cultural influence in the international society and competitiveness of Korea, the source of K-pop | 1. Korea’s national income and education level are high | Choi et al. [66] | |

| 2. Korea’s national conditions are stable | ||||

| 3. Korea’s level of technology is excellent | ||||

| 4. Korea’s economic influence is large | ||||

| 5. Korean culture is open | ||||

| 6. Korean culture is appealing | ||||

| 7. Korean culture is of a high standard | ||||

| 8. Korean culture is unique and preserves tradition | ||||

| 9. Korean culture has a long history and is likeable | ||||

| SNS citizenship behavior | Degree to which good information or material related to K-pop is produced and rapidly shared on SNS | 1. Sharing and providing K-pop-related information to people around me through SNS | Kim et al. [67] | |

| 2. Sharing positive opinions about K-pop-related information to people around me through SNS | ||||

| 3. Always contemplating how to share K-pop-related information to people around me through SNS | ||||

| 4. Extracting, processing, and sharing the core contents of K-pop-related information with people around me through SNS | ||||

| 5. Always contemplating whether K-pop-related information can be helpful to people around me through SNS | ||||

| Tourist behavioral intention | Degree of desire or plans to actually travel to Korea | 1. Will travel to Korea even if it is expensive | Choi et al. [66] Kwak et al. [28] Meng et al. [68] | |

| 2. Will travel to Korea even if there are cultural differences and a language barrier | ||||

| 3. Will travel to Korea even if transportation is inconvenient | ||||

| 4. Will travel to Korea even if it is far | ||||

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 618 | 49.6 |

| Female | 629 | 50.4 | |

| Age | 20s | 308 | 24.7 |

| 30s | 326 | 26.1 | |

| 40s | 311 | 24.9 | |

| 50s | 302 | 24.2 | |

| Education | High school graduate | 313 | 25.1 |

| Technical college graduate | 276 | 22.1 | |

| College graduate | 515 | 41.3 | |

| Graduate school graduate | 143 | 11.5 | |

| Monthly income (Mean) | Under $1000 | 270 | 21.7 |

| $1000–$2000 | 268 | 21.5 | |

| $2001–$3000 | 205 | 16.4 | |

| $3001–$4000 | 155 | 12.4 | |

| $4001–$5000 | 151 | 12.1 | |

| over $5000 | 198 | 15.9 | |

| Nationality | Philippines | 150 | 12.0 |

| Singapore | 156 | 12.5 | |

| Australia | 161 | 12.9 | |

| UK | 150 | 12.0 | |

| France | 170 | 13.6 | |

| US | 150 | 12.0 | |

| Canada | 160 | 12.8 | |

| South Africa | 150 | 12.0 | |

| Variable | Item | Convergent Validity | Cronbach’s Alpha | Multicollinearity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE | VIF | |||

| Producers | Producers1 | 0.856 | 0.921 | 0.745 | 0.886 | 2.271 |

| Producers2 | 0.863 | 2.252 | ||||

| Producers3 | 0.878 | 2.447 | ||||

| Producers4 | 0.856 | 2.242 | ||||

| Casting | Casting1 | 0.843 | 0.907 | 0.710 | 0.864 | 2.059 |

| Casting2 | 0.860 | 2.239 | ||||

| Casting3 | 0.849 | 2.083 | ||||

| Casting4 | 0.818 | 1.832 | ||||

| Training | Training1 | 0.836 | 0.897 | 0.686 | 0.847 | 1.880 |

| Training2 | 0.836 | 1.934 | ||||

| Training3 | 0.794 | 1.765 | ||||

| Training4 | 0.845 | 1.994 | ||||

| Producing/promotion | Producing/promotion1 | 0.835 | 0.907 | 0.710 | 0.864 | 1.964 |

| Producing/promotion2 | 0.848 | 2.109 | ||||

| Producing/promotion3 | 0.850 | 2.139 | ||||

| Producing/ promotion4 | 0.837 | 1.996 | ||||

| Social media | Social media1 | 0.859 | 0.919 | 0.741 | 0.884 | 2.370 |

| Social media2 | 0.852 | 2.292 | ||||

| Social media3 | 0.872 | 2.402 | ||||

| Social media4 | 0.860 | 2.180 | ||||

| Contents | Contents1 | 0.810 | 0.909 | 0.714 | 0.867 | 1.885 |

| Contents2 | 0.862 | 2.227 | ||||

| Contents3 | 0.850 | 2.099 | ||||

| Contents4 | 0.858 | 2.151 | ||||

| National image | National image1 | 0.740 | 0.934 | 0.611 | 0.920 | 2.116 |

| National image2 | 0.748 | 2.119 | ||||

| National image3 | 0.787 | 2.283 | ||||

| National image4 | 0.805 | 2.367 | ||||

| National image5 | 0.732 | 1.926 | ||||

| National image6 | 0.810 | 2.550 | ||||

| National image7 | 0.819 | 2.693 | ||||

| National image8 | 0.784 | 2.447 | ||||

| National image9 | 0.805 | 2.347 | ||||

| SNS citizenship behavior | SNS citizenship behavior1 | 0.903 | 0.957 | 0.816 | 0.944 | 3.576 |

| SNS citizenship behavior2 | 0.902 | 3.559 | ||||

| SNS citizenship behavior3 | 0.916 | 3.985 | ||||

| SNS citizenship behavior4 | 0.913 | 4.019 | ||||

| SNS citizenship behavior5 | 0.883 | 3.172 | ||||

| Tourist behavioral intention | Tourist behavioral intention1 | 0.910 | 0.947 | 0.817 | 0.925 | 3.341 |

| Tourist behavioral intention2 | 0.921 | 3.776 | ||||

| Tourist behavioral intention3 | 0.869 | 2.557 | ||||

| Tourist behavioral intention4 | 0.914 | 3.493 | ||||

| Variable | Producers | Casting | Training | Producing | Social Media | Contents | National Image | SNS Citizenship Behavior | Tourist Behavioral Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producers | 0.863 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Casting | 0.770 | 0.843 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Training | 0.781 | 0.799 | 0.828 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Producing | 0.766 | 0.807 | 0.800 | 0.842 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social media | 0.724 | 0.705 | 0.740 | 0.745 | 0.861 | - | - | - | - |

| Contents | 0.725 | 0.713 | 0.743 | 0.766 | 0.784 | 0.845 | - | - | - |

| National image | 0.550 | 0.544 | 0.525 | 0.563 | 0.517 | 0.533 | 0.782 | - | - |

| SNS citizenship behavior | 0.400 | 0.498 | 0.432 | 0.482 | 0.380 | 0.424 | 0.423 | 0.903 | - |

| Tourist behavioral intention | 0.434 | 0.471 | 0.447 | 0.481 | 0.436 | 0.445 | 0.659 | 0.497 | 0.904 |

| Path | SPSS | SmartPLS | GSCA Pro | JASP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | H | β | t | H | β | t | H | β | t | H | ||||

| H1a | Producers | → | NI | 0.175 | 4.187 *** | O | 0.170 | 3.327 ** | O | 0.171 | 3.054 ** | O | 0.175 | 4.217 *** | O |

| H1b | Casting | → | NI | 0.124 | 2.814 ** | O | 0.125 | 2.440 * | O | 0.128 | 2.723 ** | O | 0.128 | 2.902 ** | O |

| H1c | Training | → | NI | 0.000 | −0.001 | X | 0.004 | 0.090 | X | 0.001 | 0.022 | X | −0.004 | −0.099 | X |

| H1d | Producing/ Promotion | → | NI | 0.177 | 3.834 *** | O | 0.178 | 3.161 ** | O | 0.180 | 3.462 ** | O | 0.181 | 3.920 *** | O |

| H2a | Social media | → | NI | 0.072 | 1.773 | X | 0.074 | 1.785 | X | 0.073 | 1.698 | X | 0.072 | 1.770 | X |

| H2b | Contents | → | NI | 0.125 | 2.983 ** | O | 0.123 | 2.497 * | O | 0.123 | 2.412 * | O | 0.122 | 2.927 ** | O |

| - | R = 0.605, R2 = 0.367, F = 119.589 (p = 0.000) | - | - | - | |||||||||||

| H3a | Producers | → | SNS CB | −0.060 | −1.341 | X | −0.093 | 2.001 * | X | −0.094 | −1.918 | X | −0.096 | −2.160 | X |

| H3b | Casting | → | SNS CB | 0.326 | 6.876 *** | O | 0.301 | 5.521 *** | O | 0.301 | 5.017 *** | O | 0.303 | 6.520 *** | O |

| H3c | Training | → | SNS CB | 0.001 | 0.027 | X | −0.002 | 0.035 | X | 0.001 | 0.021 | X | 0.003 | 0.066 | X |

| H3d | Producing/ Promotion | → | SNS CB | 0.226 | 4.552 *** | O | 0.190 | 3.029 ** | O | 0.191 | 2.653 ** | O | 0.189 | 3.857 *** | O |

| H4a | Social media | → | SNS CB | −0.059 | −1.346 | X | −0.069 | 1.286 | X | −0.074 | −1.276 | X | −0.073 | −1.701 | X |

| H4b | Contents | → | SNS CB | 0.106 | 2.357 * | O | 0.082 | 1.507 | X | 0.083 | 1.627 | X | 0.081 | 1.841 | X |

| - | R = 0.519, R2 = 0.270, F = 76.312 (p = 0.000) | - | - | - | |||||||||||

| H5 | NI | → | SNS CB | 0.419 | 16.264 *** | O | 0.197 | 5.280 *** | O | 0.196 | 5.158 *** | O | 0.197 | 6.589 *** | O |

| R = 0.419, R2 = 0.175, F = 264.527 (p = 0.000) | |||||||||||||||

| H6 | NI | → | TBI | 0.542 | 24.270 *** | O | 0.545 | 21.922 *** | O | 0.546 | 21.000 *** | O | 0.541 | 24.214 *** | O |

| H7 | SNS CB | → | TBI | 0.270 | 12.087 *** | O | 0.266 | 9.918 *** | O | 0.266 | 9.172 *** | O | 0.269 | 12.029 *** | O |

| - | R = 0.699, R2 = 0.489, F = 594.543 (p = 0.000) | SRMR = 0.037, NFI = 0.898 | SRMR = 0.027, GFI = 0.997 | CFI = 0.959, GFI = 0.908, NFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.955, SRMR = 0.028, RMSEA = 0.041 | |||||||||||

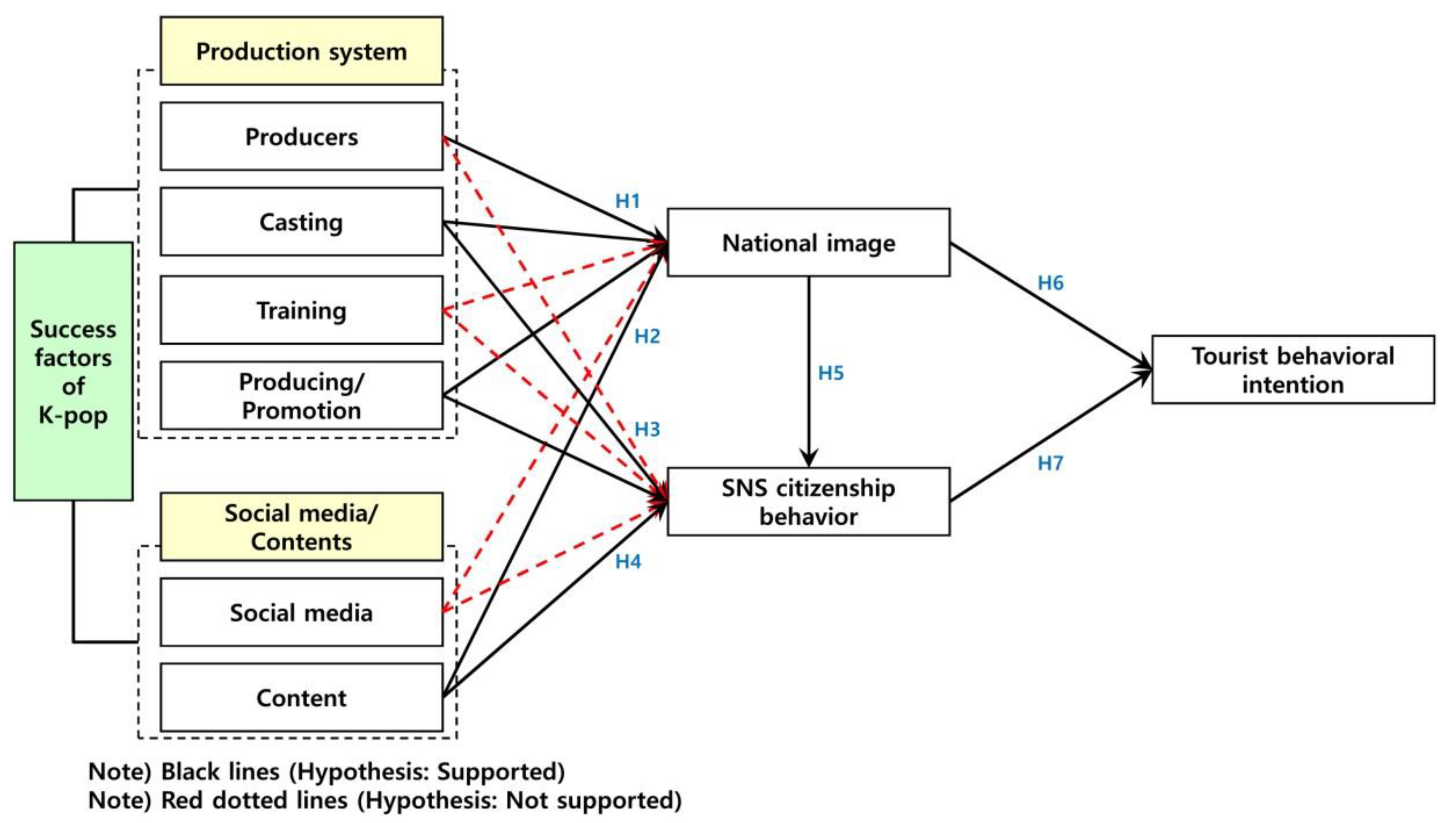

| Path | Hypothesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Producers | → | National image | Supported |

| H1b | Casting | → | National image | Supported |

| H1c | Training | → | National image | Not supported |

| H1d | Producing/promotion | → | National image | Supported |

| H2a | Social media | → | National image | Not supported |

| H2b | Contents | → | National image | Supported |

| H3a | Producers | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Not supported |

| H3b | Casting | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Supported |

| H3c | Training | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Not supported |

| H3d | Producing/promotion | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Supported |

| H4a | Social media | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Not supported |

| H4b | Contents | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Partially supported |

| H5 | National image | → | SNS citizenship behavior | Supported |

| H6 | National image | → | Tourist behavioral intention | Supported |

| H7 | SNS citizenship behavior | → | Tourist behavioral intention | Supported |

| Path | β | t | p | Mediated Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Producers → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.009 | 2.445 | 0.015 | Yes |

| 2 | Casting → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.007 | 2.263 | 0.024 | Yes |

| 3 | Training → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.925 | No |

| 4 | Producing → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.009 | 2.630 | 0.009 | Yes |

| 5 | Social media → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.004 | 1.545 | 0.123 | No |

| 6 | Contents → national image → SNS citizenship behavior → tourist behavioral intention | 0.006 | 2.079 | 0.038 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-h.; Kim, K.-j.; Park, B.-t.; Choi, H.-j. The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063200

Kim J-h, Kim K-j, Park B-t, Choi H-j. The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063200

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Joon-ho, Kwang-jin Kim, Bum-tae Park, and Hyun-ju Choi. 2022. "The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063200

APA StyleKim, J.-h., Kim, K.-j., Park, B.-t., & Choi, H.-j. (2022). The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention. Sustainability, 14(6), 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063200