Improving Local Food Systems through the Coordination of Agriculture Supply Chain Actors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Food System

2.2. Food Hubs

3. Methodological Approach

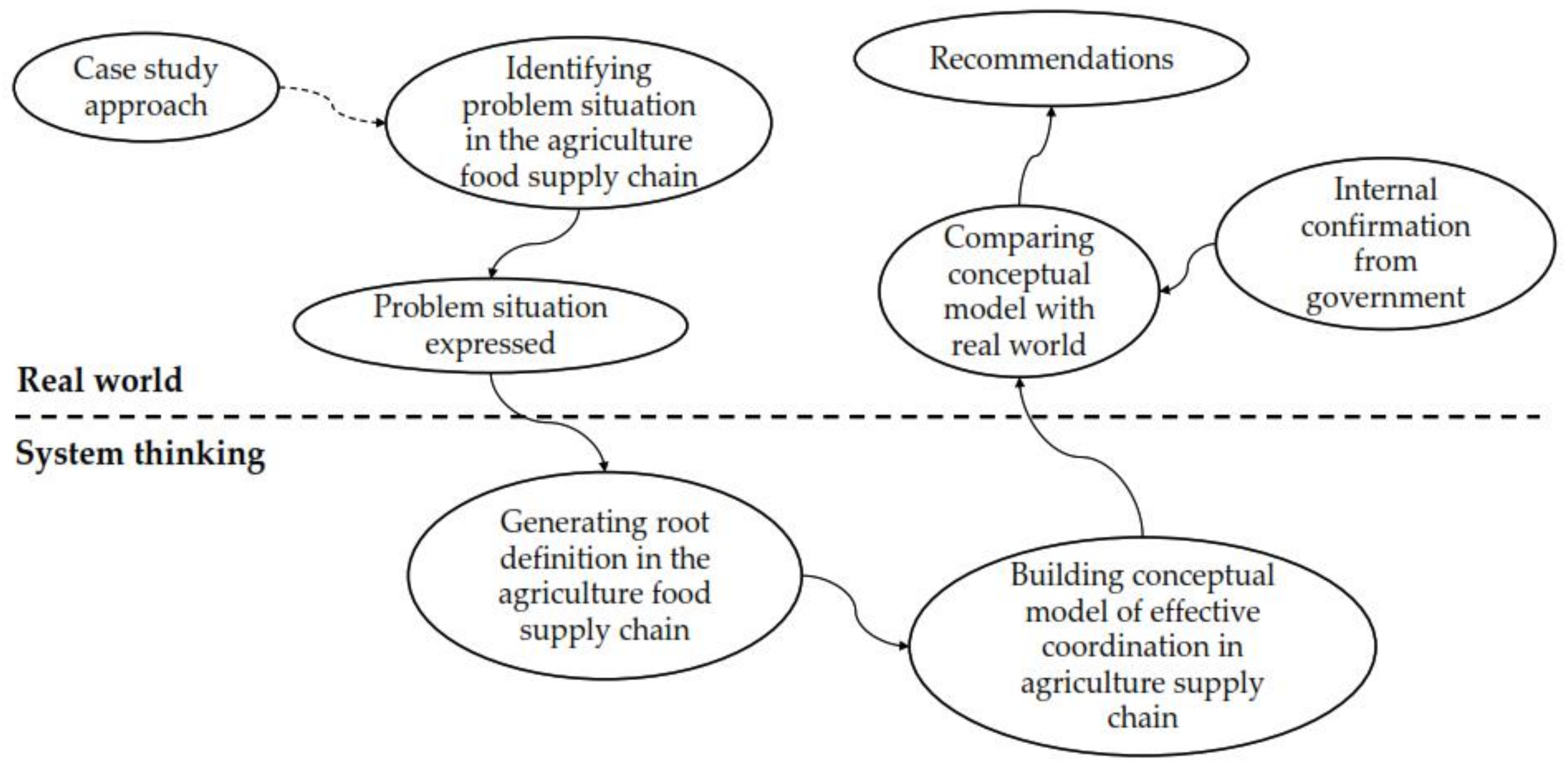

3.1. Soft System Methodology (SSM)

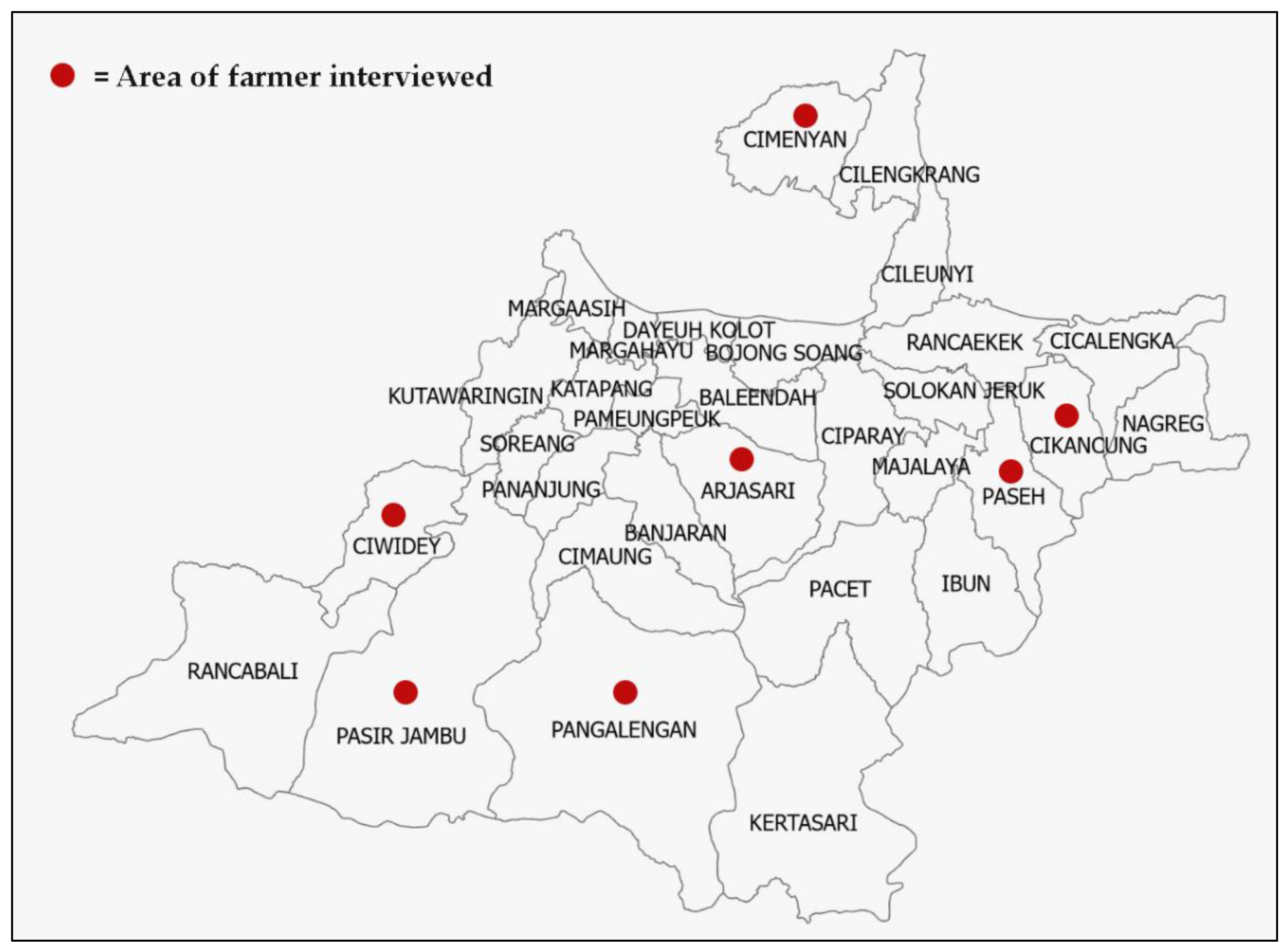

3.2. Case Study Approach

- Identifying the parties directly involved in the supply chain activities of agriculture commodities;

- Identifying the character of each actor directly involved in the supply chain of agricultural commodities in Bandung Regency;

- Determining how farmers decide to whom they will sell their commodities, and what their considerations are;

- Determining how customers decide from whom they buy commodities, and what their considerations are.

4. Results and Discussion

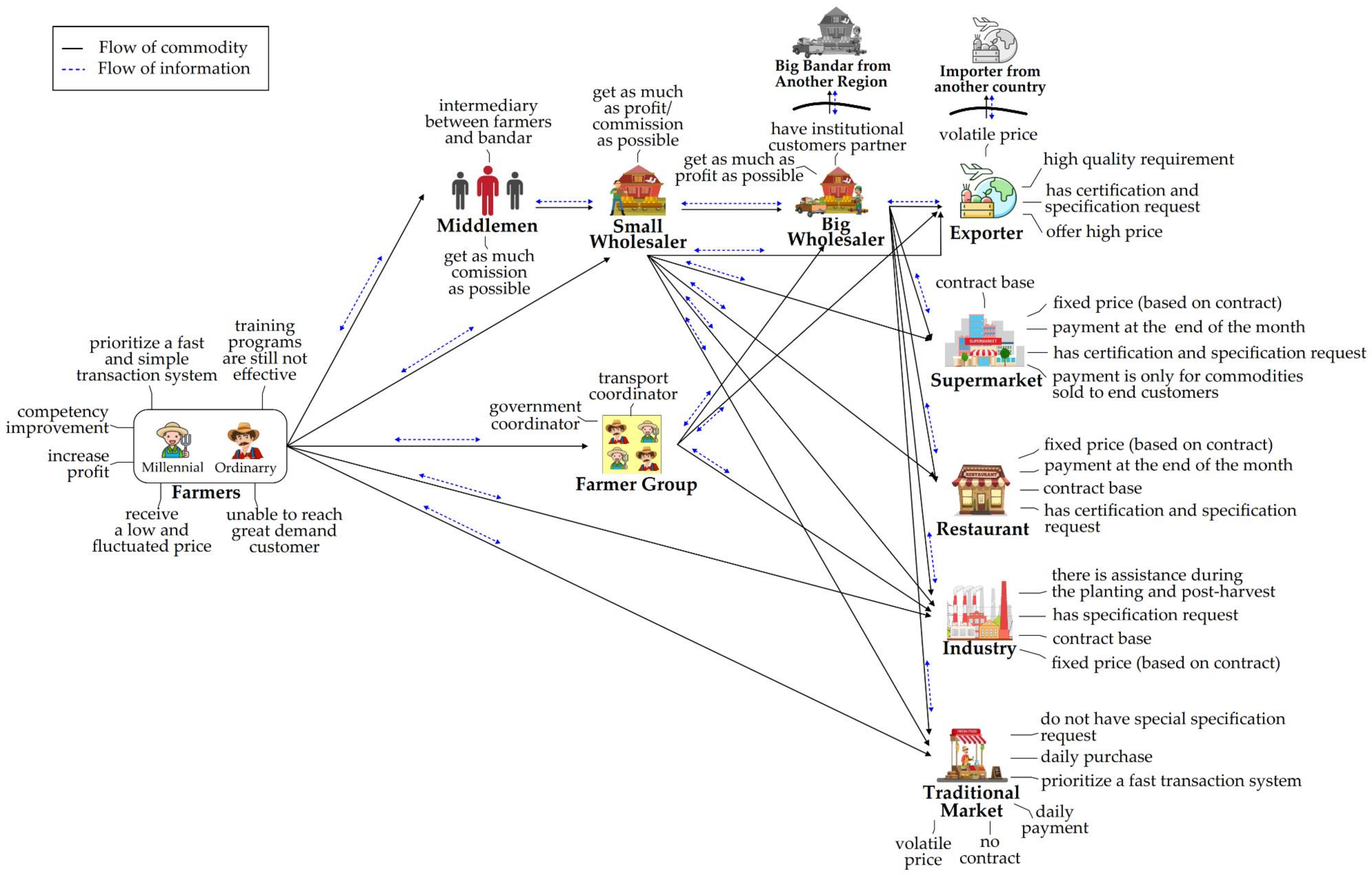

4.1. The Real-World Situation in the Agriculture Supply Chain in Bandung Regency

4.2. Root Definition

4.3. Conceptual Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Musavi, M.M.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A. A multi-objective sustainable hub location-scheduling problem for perishable food supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 113, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Nagurney, A. Competitive food supply chain networks with application to fresh produce. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 224, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyson, T.A.; Guptill, A. Commodity agriculture, civic agriculture and the future of U.S. farming. Rural Sociol. 2004, 69, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany McFadden, D.; Conner, D.; Deller, S.; Hughes, D.; Meter, K.; Morales, A.; Schmit, T.; Swenson, D.; Bauman, A.; Phillips Goldenberg, M.; et al. The Economics of Local Food Systems: A Toolkit to Guide Community Discussions, Assessments and Choices; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 118. [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.C.; Lamie, D.; Stickel, M. Local foods systems and community economic development. Community Dev. 2017, 48, 612–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Thilmany, D.; Jablonski, B.B.R. Evaluating scale and technical efficiency among farms and ranches with a local market orientation. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 34, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Aussenberg, R.A.; Cowan, T. The role of local food systems in U.S. farm policy. In Local and Regional Food Systems: Trends, Resources and Federal Initiatives; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–86. ISBN1 9781634827768. ISBN2 9781634827751. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, A.; Newton, J.; Mcentee, J.C. Moving beyond the alternative: Sustainable communities, rural resilience and the mainstreaming of local food. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, M.A.; Kennedy, E.H.; Wittman, H. Scaling up alternative food networks: Farmers’ markets and the role of clustering in western Canada. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Ferrara, M.; Raso, C.; Violi, A. Collaborative organization models for sustainable development in the agri-food sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakias, Z.T.; Demko, I.; Katchova, A.L. Direct marketing channel choices among US farmers: Evidence from the Local Food Marketing Practices Survey. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winarno, H.; Perdana, T.; Handayati, Y.; Purnomo, D. Food hubs and short food supply chain, efforts to realize regional food distribution center (Case study on the establishment of a food distribution center in Banten province, Indonesia). Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 9, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of small farms and innovative food supply chains: The role of food hubs in creating sustainable regional and local food systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ioannis, M.; George, M.; Socrates, M. A community-based Agro-Food Hub model for sustainable farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fischer, M.; Pirog, R.; Hamm, M.W. Food Hubs: Definitions, Expectations, and Realities. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2015, 10, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, T.; Brent Ross, R. The intersection of social and economic value creation in social entrepreneurship: A comparative case study of food hubs. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2019, 50, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Palmer, A.; Landman, K.; Knezevic, I.; Hayhurst, R. Constructing resilient, transformative communities through sustainable “food hubs”. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.S.; Harrington, H.; Heiss, S.; Berlin, L. How Can Food Hubs Best Serve Their Buyers? Perspectives from Vermont. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, J.; Conner, D.; McRae, G.; Darby, H. Building Resilience in Nonprofit Food Hubs. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2014, 4, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barham, J.; Tropp, D.; Enterline, K.; Farbman, J.; Fisk, J.; Kiraly, S. Regional Food Hub Resource Guide; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 92. [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Müller, N.M.; Tranovich, A.C.; Mazaroli, D.N.; Hinson, K. Local food hubs for alternative food systems: A case study from Santa Barbara County, California. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Dalia, C.; Salvati, L.; Salvia, R. Building resilience: An art-food hub to connect local communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, K.; Hamm, M.W. The Role of Values in Food Hub Sourcing and Distributing Practices. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2015, 10, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, G.; Granados-Rivera, D.; Jarrín, J.A.; Castellanos, A.; Mayorquín, N.; Molano, E. Strategic supply chain planning for food hubs in central colombia: An approach for sustainable food supply and distribution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, T.; Chaerani, D.; Achmad, A.L.H.; Hermiatin, F.R. Scenarios for handling the impact of COVID-19 based on food supply network through regional food hubs under uncertainty. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Canning, P.; Goetz, S.; Perez, A. Effects of scale economies and production seasonality on optimal hub locations: The case of regional fresh produce aggregation. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, R.; Goetz, S.J.; McFadden, D.T.; Ge, H. Excess competition among food hubs. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 44, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.W. Policies supporting local food in the United States. Agriculture 2016, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handayati, Y.; Simatupang, T.M.; Perdana, T. Agri-food supply chain coordination: The state-of-the-art and recent developments. Logist. Res. 2015, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C. A hybrid simulation modeling framework for regional food hubs. J. Simul. 2019, 13, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroink, M.L.; Nelson, C.H. Complexity and food hubs: Five case studies from Northern Ontario. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.; Thayer, J.; Shaw, J. Running a Food Hub: Lessons Learned from the Field; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 51. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Le, T.M.; Kingsbury, A.J. Farmer participation in the lychee value chain in Bac Giang province, Vietnam. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, X.; Cai, C.; Guan, S. Computers and Operations Research Supply chain coordination of fresh agricultural products based on consumer behavior. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Islam, S.M.N.; Liu, X. Coordinating a three-echelon fresh agricultural products supply chain considering freshness-keeping effort with asymmetric information. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 67, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Subramanian, N. Impact of disruptions in agri-food supply chain due to COVID-19 pandemic: Contextualised resilience framework to achieve operational excellence. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal Vieira, L.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Howes, M. Daring to build fair and sustainable urban food systems: A case study of alternative food networks in Australia. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 45, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, P.; Taherzadeh, A. Working co-operatively for sustainable and just food system transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C. A hybrid simulation model of inbound logistics operations in regional food supply systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings-Winter Simulation Conference, Huntington Beach, CA, USA, 6–9 December 2015; pp. 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Checkland, P.; Poulter, J. Soft systems methodology. In Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 201–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Soft systems methodology: A thirty year retrospective. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2000, 17, S11–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ulloa, R.; Paucar-Caceres, A. Soft system dynamics methodology (SSDM): Combining soft systems methodology (SSM) and system dynamics (SD). Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2005, 18, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauger, A. Social agency and networked spatial relations in sustainable agriculture. Area 2009, 41, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, L.; Van den Broeck, G. Local food systems: Reviewing two decades of research. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Bonanno, A.; Nardone, G.; Viscecchia, R. The hidden benefits of short food supply chains: Farmers’ markets density and body mass index in Italy. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrada-Serra, P.; Moragues-Faus, A.; Zwart, T.A.; Adlerova, B.; Ortiz-Miranda, D.; Avermaete, T. Exploring the contribution of alternative food networks to food security. A comparative analysis. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1371–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaker, M.; Kolodinsky, J.; Wang, W.; Chase, L.C.; Van, J.; Kim, S.; Smith, D.; Estrin, H.; Van Vlaanderen, Z.; Greco, L. Evaluation of Farm Fresh Food Boxes: A Hybrid Alternative Food Network Market Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M. Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes toward Local Food Products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.; Bediako, A.; Capers, T.; Kirac, A.; Freudenberg, N. Creating Integrated Strategies for Increasing Access to Healthy Affordable Food in Urban Communities: A Case Study of Intersecting Food Initiatives. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarikidou, K.; Kaloudis, H.; Fielden, A.; Reynolds, C. Local food hubs in deprived areas: De-stigmatising food poverty? Local Environ. 2019, 24, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.; Cook, C.; Sullins, M. The Role of Food Hubs in Local Food Marketing. USDA Rural Dev. 2013, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.S.; Sims, K.; Berkfield, R.; Harrington, H. Do farmers and other suppliers benefit from sales to food hubs? Evidence from Vermont. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.A.; Bell, B.A.; Clark, J.; Ngendahimana, D.; Borawski, E.; Trapl, E.; Pike, S.; Sehgal, A.R. Small Improvements in an Urban Food Environment Resulted in No Changes in Diet Among Residents. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, G.W.; Clancy, K.; King, R.; Lev, L.; Ostrom, M.; Smith, S. Midscale Food Value Chains: An Introduction. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2011, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.B. Soft systems methodology. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1989, 8, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafizadeh, P.; Mehrabioun, M. Application of SSM in tackling problematical situations from academicians’ viewpoints. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2018, 31, 179–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5, ISBN 1412960991. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, L.T. The strengths and weaknesses of research methodology: Comparison and complimentary between qualitative and quantitative approaches. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 19, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hermanto, R.; Putro, U.S.; Novani, S.; Kijima, K. Overcoming the challenge of those new with SSM in surfacing relevant worldviews for action to improve. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, I. Messing about in transformations: Structured systemic planning for systemic solutions to systemic problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 223, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Mirijamdotter, A.; Basden, A. Basic principles of SSM modeling: An examination of CATWOE from a soft perspective. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2004, 17, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basden, A.; Wood-Harper, A.T. A philosophical discussion of the root definition in soft systems thinking: An enrichment of CATWOE. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. Off. J. Int. Fed. Syst. Res. 2006, 23, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1506330193. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Farmer Group Name | Number of Farmer Members | Channel in Selling Harvest | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middlemen | Small Wholesaler | Farmers Group | Traditional Market | Industry | |||

| Ciwidey | A | 35 | - | √ | √ | √ | - |

| B | 40 | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| C | 270 | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Pasirjambu | D | 20 | - | √ | - | - | - |

| E | 170 | - | - | √ | √ | - | |

| Pangalengan | F | 25 | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Arjasari | G | 70 | - | √ | - | - | - |

| Paseh | H | 30 | √ | √ | - | - | - |

| Cikancung | I | 60 | - | √ | √ | - | - |

| Cimenyan | J | 30 | √ | √ | - | - | - |

| K | 77 | √ | √ | - | - | - | |

| High Demand Customer | Requirements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Certification | Contract Base | |

| Traditional Markets | no specific grade | no | no |

| Supermarkets | A | yes | yes |

| Restaurants | B, C | no | yes |

| Industry | A | yes | yes |

| Exporters | A | yes | yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anggraeni, E.W.; Handayati, Y.; Novani, S. Improving Local Food Systems through the Coordination of Agriculture Supply Chain Actors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063281

Anggraeni EW, Handayati Y, Novani S. Improving Local Food Systems through the Coordination of Agriculture Supply Chain Actors. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063281

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnggraeni, Efryta Wulan, Yuanita Handayati, and Santi Novani. 2022. "Improving Local Food Systems through the Coordination of Agriculture Supply Chain Actors" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063281

APA StyleAnggraeni, E. W., Handayati, Y., & Novani, S. (2022). Improving Local Food Systems through the Coordination of Agriculture Supply Chain Actors. Sustainability, 14(6), 3281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063281