Toward the Development and Validation of a Model of Environmental Citizenship of Young Adults

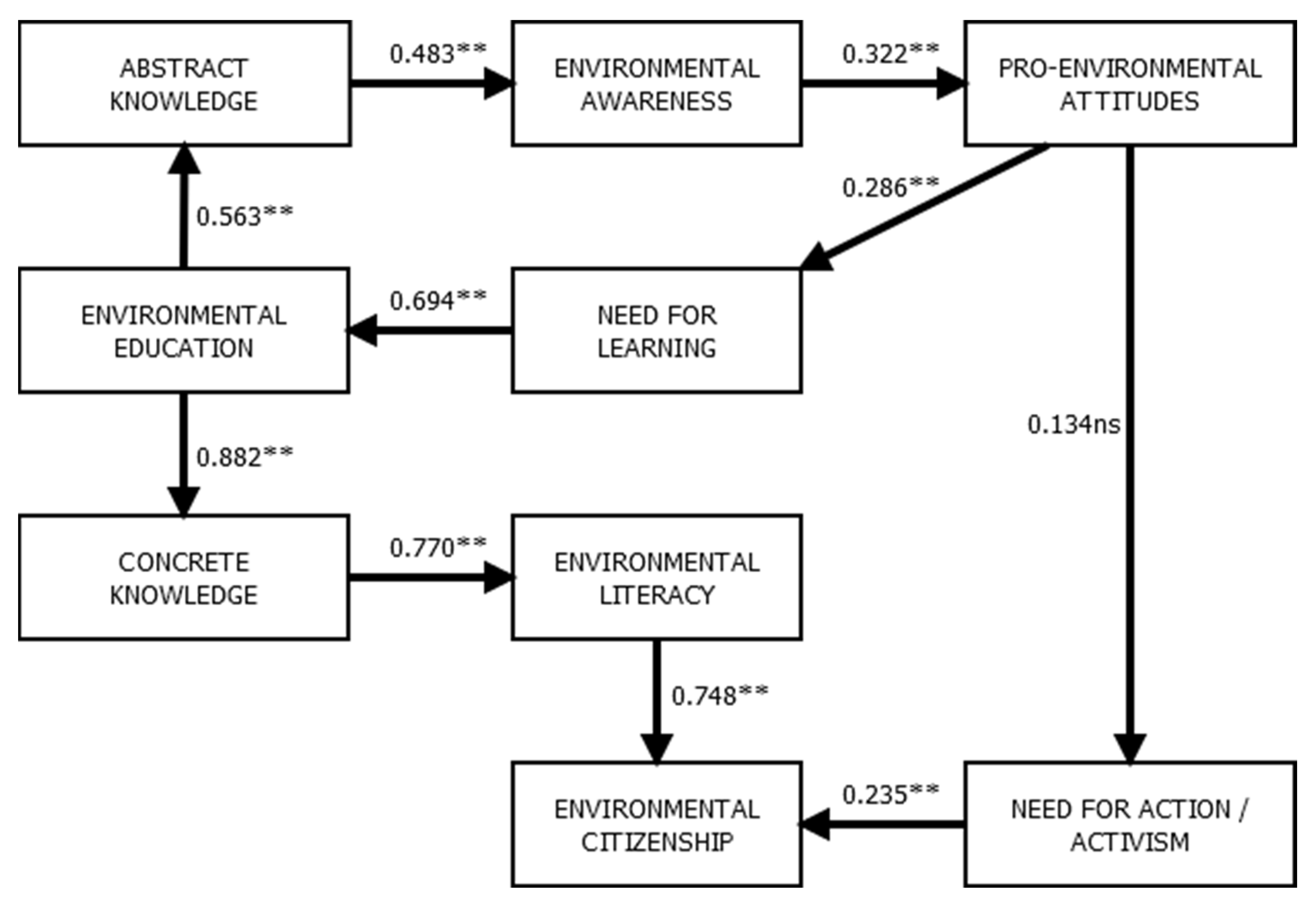

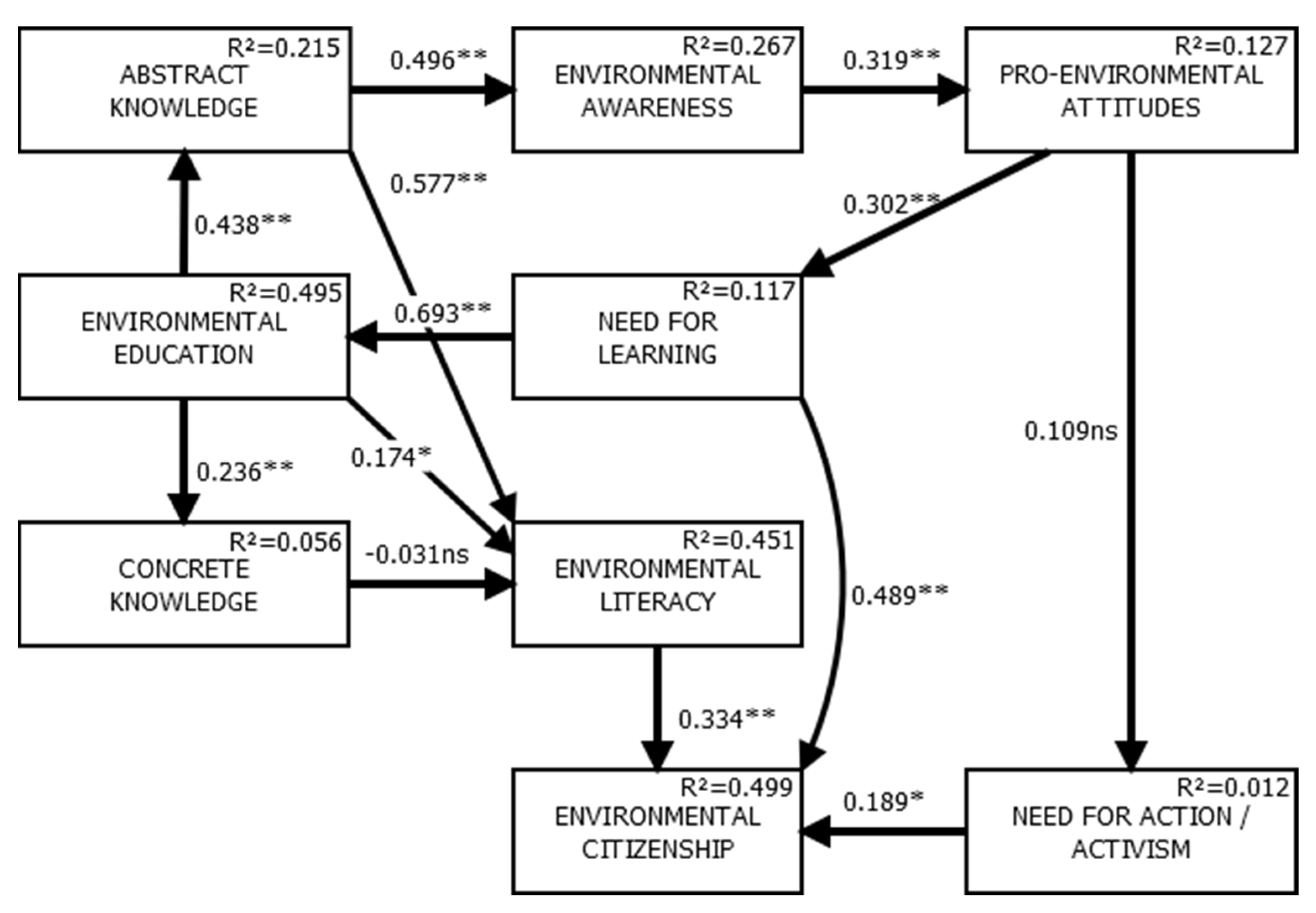

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Components of the Model

1.1.1. Need for Learning

1.1.2. Abstract Environmental Knowledge

1.1.3. Concrete Environmental Knowledge

1.1.4. Environmental Awareness (Consciousness)

1.1.5. Environmental Attitudes

1.1.6. Environmental (Self-)Education

1.1.7. Environmental Literacy

1.1.8. Environmental Citizenship

1.1.9. Need for Action

1.2. Relationships between the Components of the Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Characteristics

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Variables

2.3.2. Political Beliefs

2.3.3. Personality Traits

2.3.4. Need for Learning

2.3.5. Abstract Environmental Knowledge

2.3.6. Concrete Environmental Knowledge

2.3.7. Environmental Awareness (Consciousness)

2.3.8. Environmental Attitudes

2.3.9. Environmental (Self-)Education

2.3.10. Environmental Literacy

2.3.11. Environmental Citizenship

2.3.12. Need for Action

2.4. Analysis Strategy and Data Availability

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items Used in the Study |

|---|

| Need for learning (developed based on the Attitude/Motivation Test Battery [37]) |

| When learning how to be environmentally friendly, I would prefer more attention to be given to facts and not games |

| If I had a chance to learn about how I can better take care of the environment, I would jump at the opportunity |

| Learning about how one can be more environmentally friendly is more interesting to me when compared to learning about other topics |

| If there was a club at my school/university/workplace of environmentally minded people, I would definitely join it |

| If I could choose what I have to learn, I would definitely add being environmentally friendly to the list |

| It is interesting to me to learn about how I can be more environmentally friendly |

| If I have a chance to participate in an event focused on being more environmentally friendly, I jump at the opportunity |

| I like to discuss how one can be more environmentally friendly with my friends |

| If there were communities focused on being environmentally friendly near me, I would definitely join them |

| If I knew how to get the best information on how to be more environmentally friendly, I would definitely be interested in it |

| Abstract environmental knowledge (adapted from Kim & Stepchenkova [19] and Mohiuddin et al. [20]) |

| I have good knowledge regarding environmental issues |

| I understand the various labels on products that provide information on their environmental impact |

| I know how to distinguish environmentally friendly products |

| I know how to recycle properly |

| I know how to choose the most environmentally friendly transportation option |

| Environmental awareness (adapted from Mohiuddin et al. [20])I know what the consequences of climate change are |

| I know the impact pollution has on the environment |

| If we used less energy, environmental problems would also lessen |

| If we consumed less, environmental problems would also lessen |

| Environmental (self-)education (scale designed for this study) |

| During the past month I did research on environmental issues |

| During the past month I refreshed my understanding of the most environmentally friendly modes of transportation |

| During the past month I refreshed my understanding on what the most environmentally friendly food options are |

| During the past month I refreshed my understanding on what human activities are the most harmful to the environment |

| During the past month I refreshed my understanding on what the most environmentally friendly energy sources are |

| During the past month, while refreshing my understanding of environmental issues, I learnt something new (NOT USED IN THE STUDY) |

| During the past month, while refreshing my understanding of environmental issues, I learnt something that is true, but is inconsistent with my views (NOT USED IN THE STUDY) |

| During the past month, while refreshing my understanding of environmental issues, I learnt something that changed my prior held beliefs (NOT USED IN THIS STUDY) |

References

- Gunningham, N. Averting Climate Catastrophe: Environmental Activism, Extinction Rebellion and coalitions of Influence. King’s Law J. 2019, 30, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Reis, P. Introduction to the Conceptualisation of Environmental Citizenship for Twenty-First-Century Education. In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education. Environmental Discourses in Science Education; Hadjichambis, A.C., Reis, P., Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Činčera, J., Pauw, J.B., Gericke, N., Knippels, M.-C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, M.; Alabaster, T. Citizen 2000: Development of a model of environmental citizenship. Glob. Environ. Chang. 1999, 9, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D. Environmental Citizenship Questionnaire (ECQ): The Development and Validation of an Evaluation Instrument for Secondary School Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D. Education for Environmental Citizenship: The Pedagogical Approach. In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, P. Environmental Citizenship and Youth Activism. In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Poškus, M.S.; Balundė, A.; Jovarauskaitė, L. SWOT Analysis of Environmental Citizenship Education in Lithuania. In European SWOT Analysis on Education for Environmental Citizenship; Hadjichambis, A.C., Reis, P., Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Eds.; Intitute of Education—University of Lisbon, Cyprus Centre for Environmental Research and Education & European Network for Environmental Citizenship—ENEC Cost Action: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; ISBN 978-9963-9275-6-2. [Google Scholar]

- ENEC Defining “Environmental Citizenship”. Available online: http://enec-cost.eu/our-approach/enec-environmental-citizenship/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Dobson, A. Environmental citizenship: Towards sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telešienė, A.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Goldman, D.; Hansmann, R. Evaluating an Educational Intervention Designed to Foster Environmental Citizenship among Undergraduate University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Educating the Global Environmental Citizen; Series: Critical global citizenship education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781315204345. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.R.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Olsson, D.; Van Petegem, P.; Parra, G.; Gericke, N. Promoting Environmental Citizenship in Education: The Potential of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire to Measure Impact of Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T.J.C.; Benyamin, B.; de Leeuw, C.A.; Sullivan, P.F.; van Bochoven, A.; Visscher, P.M.; Posthuma, D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrik, A. Core Concept “Political Compass” How Kitschelt’s Model of Liberal, Socialist, Libertarian and Conservative Orientations Can Fill the Ideology Gap in Civic Education. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2010, 9, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P. Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J. Res. Pers. 2017, 68, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkholt, E.; Ørbæk, T.; Kindeberg, T. An outline of a pedagogical rhetorical interactional methodology—Researching teachers’ responsibility for supporting students’ desire to learn as well as their actual learning. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G. Research on the Influence of Online Learning on Students’ Desire to Learn. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1693, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Stepchenkova, S. Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Syed, F.; Mehedi Masud, M.; Su, Z. Environmental Knowledge, Awareness, and Business School Students’ Intentions to Purchase Green Vehicles in Emerging Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovarauskaitė, L.; Balundė, A.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I.; Kaniušonytė, G.; Žukauskienė, R.; Poškus, M.S. Toward Reducing Adolescents’ Bottled Water Purchasing: From Policy Awareness to Policy-Congruent Behavior. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402098329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Blöbaum, A. A comprehensive action determination model: Toward a broader understanding of ecological behaviour using the example of travel mode choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: From Marginality to Worldwide Use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. An evolutionary approach to the extraversion continuum. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2005, 26, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poškus, M.S.; Žukauskienė, R. Predicting adolescents’ recycling behavior among different big five personality types. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poškus, M.S. Normative Influence of pro-Environmental Intentions in Adolescents with Different Personality Types. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Y.; Hadjichambis, A.C.; Hadjichambi, D. Teachers’ Perceptions on Environmental Citizenship: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Bogner, F.X. Modelling environmental literacy with environmental knowledge, values and (reported) behaviour. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 65, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, G.L.; Teixeira Da Rocha, J.B. Environmental Education Program as a Tool to Improve Children’s Environmental Attitudes and Knowledge. Education 2018, 8, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, T.; Cottrell, R.; Dierkes, P. Fostering changes in attitude, knowledge and behavior: Demographic variation in environmental education effects. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Eberstein, K.; Scott, D.M. Birds in the playground: Evaluating the effectiveness of an urban environmental education project in enhancing school children’s awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards local wildlife. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R.; Ojeda, M.; Mora-Merchán, J.A.; Nieves Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Morgado, B.; Lasaga, M.J. Environmental education: Effects on knowledge, attitudes and perceptions, and gender differences. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P. Understanding the psychology X politics interaction behind environmental activism: The roles of governmental trust, density of environmental NGOs, and democracy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. The Attitude/Motivation Test Battery: Technical Report, 1985.

- Leeming, F.C.; Dwyer, W.O.; Bracken, B.A. Children’s Environmental Attitude and Knowledge Scale: Construction and Validation. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 26, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P. The comparison of estimation methods on the parameter estimates and fit indices in SEM model under 7-point Likert scale. Arch. Data Sci. 2017, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H. The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.É.; Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savalei, V. Understanding Robust Corrections in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, B.; Neale, M.C. Best Practices for Binary and Ordinal Data Analyses. Behav. Genet. 2021, 51, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.W.; Fang, W.T.; Yeh, S.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Tsai, H.M.; Chou, J.Y.; Ng, E. A nationwide survey evaluating the environmental literacy of undergraduate students in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, S.; Goldman, D.; Yavetz, B. Environmental literacy in teacher training: Attitudes, knowledge, and environmental behavior off beginning students. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 39, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffarth, M.R.; Hodson, G. Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C. Expanding the range of environmental values: Political orientation, moral foundations, and the common ingroup. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, S.J.N. The Influence of Neuroticism on Proenvironmental Behavior. Bachelor’s Thesis, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, 2015; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford, T.K. Recycling, evolution and the structure of human personality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2006, 41, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poškus, M.S. Personality and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 969–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B. Personality and environmental concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poškus, M.S. What Works for Whom? Investigating Adolescents’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, L.-G. Combining Holism and Interactionism. Towards a Conceptual Clarification. J. Pers. Res. 2015, 1, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bergman, L.R.; El-Khouri, B.M. A person-oriented approach: Methods for today and methods for tomorrow. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2003, 2003, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrone, M.; Mancl, K.; Carr, K. Development of a Metric to Test Group Differences in Ecological Knowledge as One Component of Environmental Literacy. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wei, J.; Zhao, D. Anti-nuclear behavioral intentions: The role of perceived knowledge, information processing, and risk perception. Energy Policy 2016, 88, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M (SD) | S | K | r | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||||

| 1. Age | 23.8 (4.85) | 1.320 | 1.280 | — | |||||||||||

| 2. Income (in Euros) | 547 (484) | 1.470 | 2.92 | 0.568 *** | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Expenses (in Euros) | 189 (164) | 1.560 | 4.760 | 0.385 *** | 0.462 *** | — | |||||||||

| 4. Leftover income (in Euros) | 356 (433) | 1.610 | 4.160 | 0.493 *** | 0.942 *** | 0.135 * | — | ||||||||

| 5. Need for learning about environmental issues | 3.12 (0.833) | −0.049 | −0.380 | 0.104 | 0.002 | 0.053 | −0.021 | — | |||||||

| 6. Abstract environmental knowledge | 3.54 (0.668) | −0.347 | 0.129 | 0.054 | 0.025 | 0.078 | −0.01 | 0.375 *** | — | ||||||

| 7. Concrete environmental knowledge | 19.5 (2.820) | −0.147 | −0.563 | 0.163 ** | 0.020 | 0.078 | −0.004 | 0.135 * | 0.154 * | — | |||||

| 8. Environ-mental awareness | 4.05 (0.657) | −0.697 | 1.890 | −0.087 | −0.123 * | −0.054 | −0.112 | 0.303 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.103 | — | ||||

| 9. Environmental attitudes (NEP) | 3.82 (0.492) | −0.257 | 0.256 | −0.112 | −0.059 | 0.010 | −0.067 | 0.322 *** | 0.144 * | 0.183 ** | 0.393 *** | — | |||

| 10. Environmental (self-)education | 2.83 (1.010) | −0.213 | −0.649 | 0.132 * | 0.044 | 0.095 | 0.005 | 0.668 *** | 0.409 *** | 0.189 ** | 0.229 *** | 0.207 *** | — | ||

| 11. Environmental literacy | 3.05 (0.675) | −0.204 | 0.803 | 0.073 | −0.008 | 0.027 | −0.028 | 0.374 *** | 0.591 *** | 0.070 | 0.426 *** | 0.083 | 0.404 *** | — | |

| 12. Environmental citizenship | 3.46 (0.851) | −0.404 | 0.355 | −0.023 | −0.037 | 0.072 | −0.071 | 0.567 *** | 0.348 *** | 0.119 | 0.384 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.463 *** | — |

| 13. Need for action | 1.51 (0.607) | 1.760 | 3.250 | −0.011 | −0.002 | 0.073 | −0.037 | 0.143 * | 0.161 ** | −0.073 | 0.033 | −0.041 | 0.190 ** | 0.106 | 0.201 *** |

| Social Political Dimension | Economic Political Dimension | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Extraversion | Openness | Neuroticism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.194 ** | −0.200 ** | −0.013 | 0.150 * | 0.162 ** | 0.021 | −0.151 * |

| Income | −0.108 | −0.097 | 0.117 | 0.222 *** | 0.187 ** | 0.012 | −0.127 * |

| Expenses | −0.083 | 0.010 | 0.070 | 0.168 ** | 0.151 * | 0.072 | −0.018 |

| Leftover income | −0.081 | −0.115 | 0.106 | 0.180 ** | 0.127 * | −0.024 | −0.127 * |

| Need for learning about environmental issues | −0.020 | 0.021 | 0.215 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.316 *** | −0.028 |

| Abstract environmental knowledge | 0.104 | 0.088 | 0.199 ** | 0.217 *** | 0.155 * | 0.261 *** | −0.166 ** |

| Concrete environmental knowledge | −0.018 | −0.371 *** | −0.129 * | 0 | −0.020 | 0.111 | −0.093 |

| Environ-mental awareness | 0.048 | 0.038 | 0.147 * | 0.161 ** | 0.086 | 0.156 * | 0.006 |

| Environmental attitudes (NEP) | 0.082 | −0.108 | 0.095 | 0.096 | −0.001 | 0.071 | 0.133 * |

| Environmental (self-)education | 0.004 | −0.027 | 0.027 | 0.121 * | 0.189 ** | 0.307 *** | −0.057 |

| Environmental literacy | −0.068 | 0.056 | 0.066 | 0.175 ** | 0.256 *** | 0.164 ** | −0.128 * |

| Environmental citizenship | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.179 ** | 0.249 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.333 *** | −0.026 |

| Need for action | −0.017 | 0.016 | 0.171 ** | 0.036 | 0.158 ** | 0.208 *** | −0.050 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poškus, M.S. Toward the Development and Validation of a Model of Environmental Citizenship of Young Adults. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063338

Poškus MS. Toward the Development and Validation of a Model of Environmental Citizenship of Young Adults. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063338

Chicago/Turabian StylePoškus, Mykolas Simas. 2022. "Toward the Development and Validation of a Model of Environmental Citizenship of Young Adults" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063338

APA StylePoškus, M. S. (2022). Toward the Development and Validation of a Model of Environmental Citizenship of Young Adults. Sustainability, 14(6), 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063338