Designing Transformation: Negotiating Solar and Green Strategies for the Sustainable Densification of Urban Neighbourhoods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

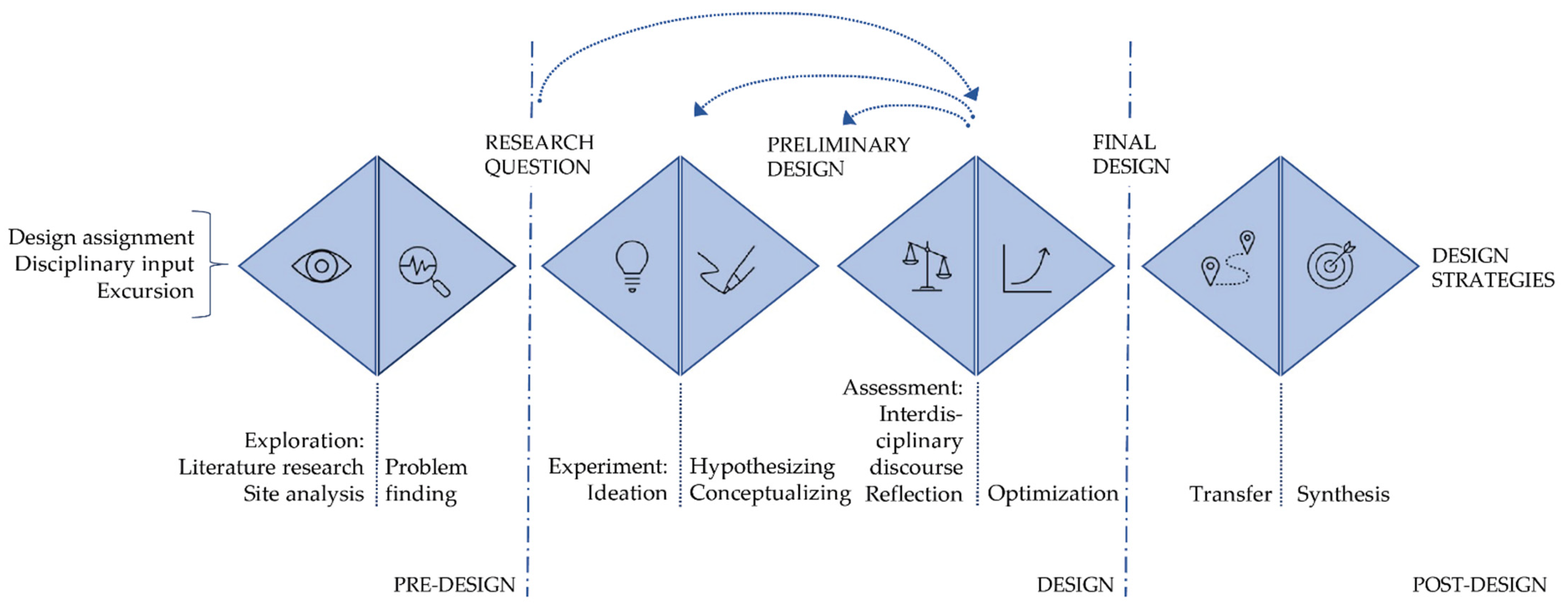

2.2. Methods

- Pre-design phase

- 2.

- Design phase

- 3.

- Post-design phase

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Design Phase

3.1.1. Literature Research and Development of Leading Questions

- Post-war buildings and districts: drawbacks and improvements in the existing building stock

- Climate resilience: local microclimate within urban districts

- Benefits of building greenery and building-integrated photovoltaics in urban districts: socio-spatial impacts and performances

- Holistic evaluation of building greenery and building-integrated photovoltaic installations for developing hybrid systems

- How can post-war neighbourhoods with building greenery and building-integrated photovoltaics be upgraded while considering socio-spatial and financial aspects?

- How can the separate arrangement of building greenery and photovoltaic modules in façades be used to optimise their ecological, economic, and social benefits?

- Which architectural/functional, planning, and decision criteria are relevant for solar and green strategies?

3.1.2. Site Analysis

3.2. Design Phase

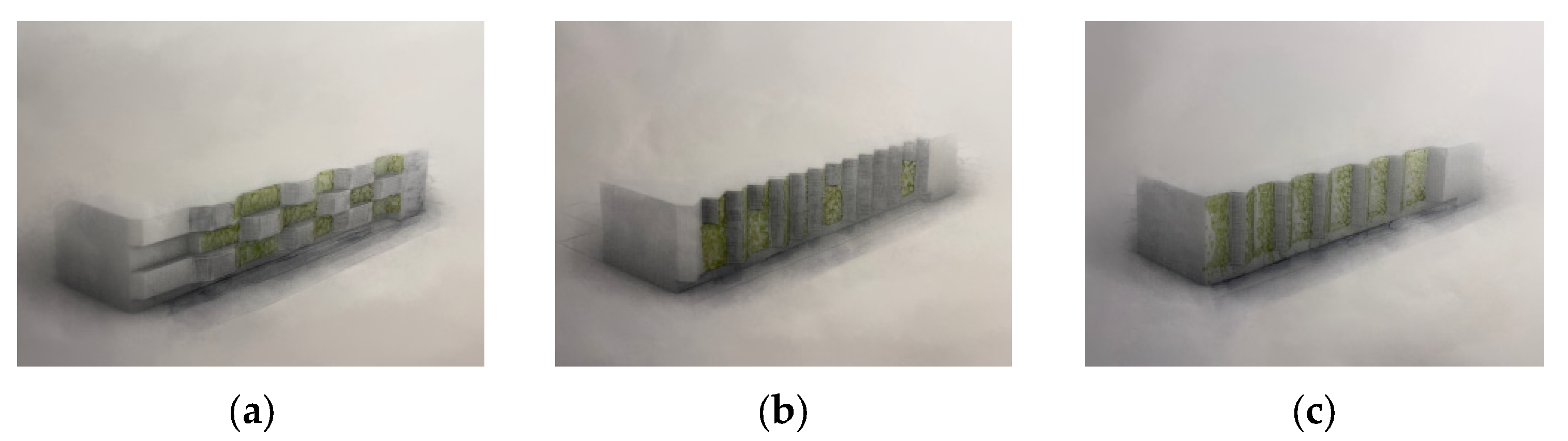

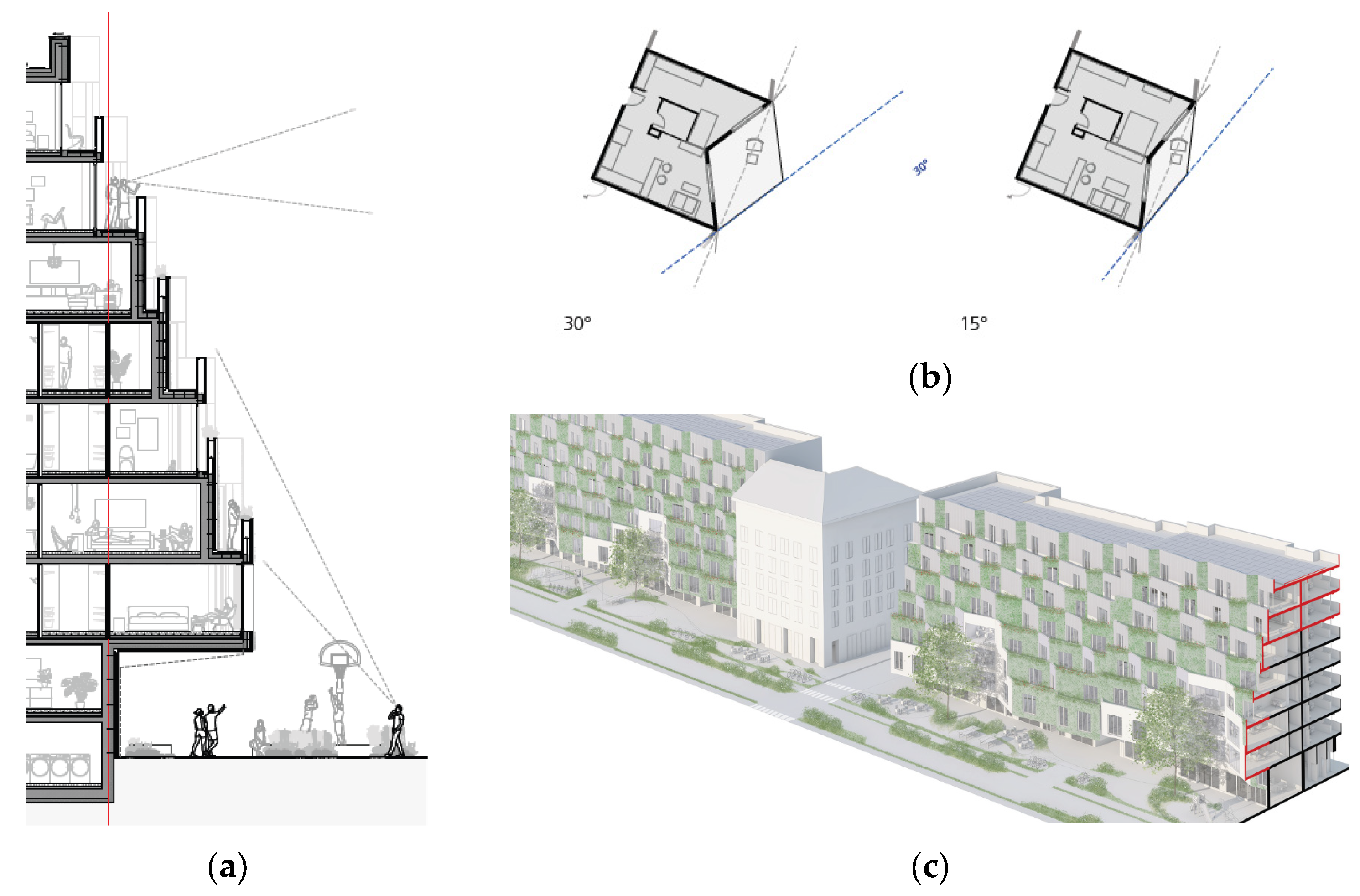

3.2.1. Modular

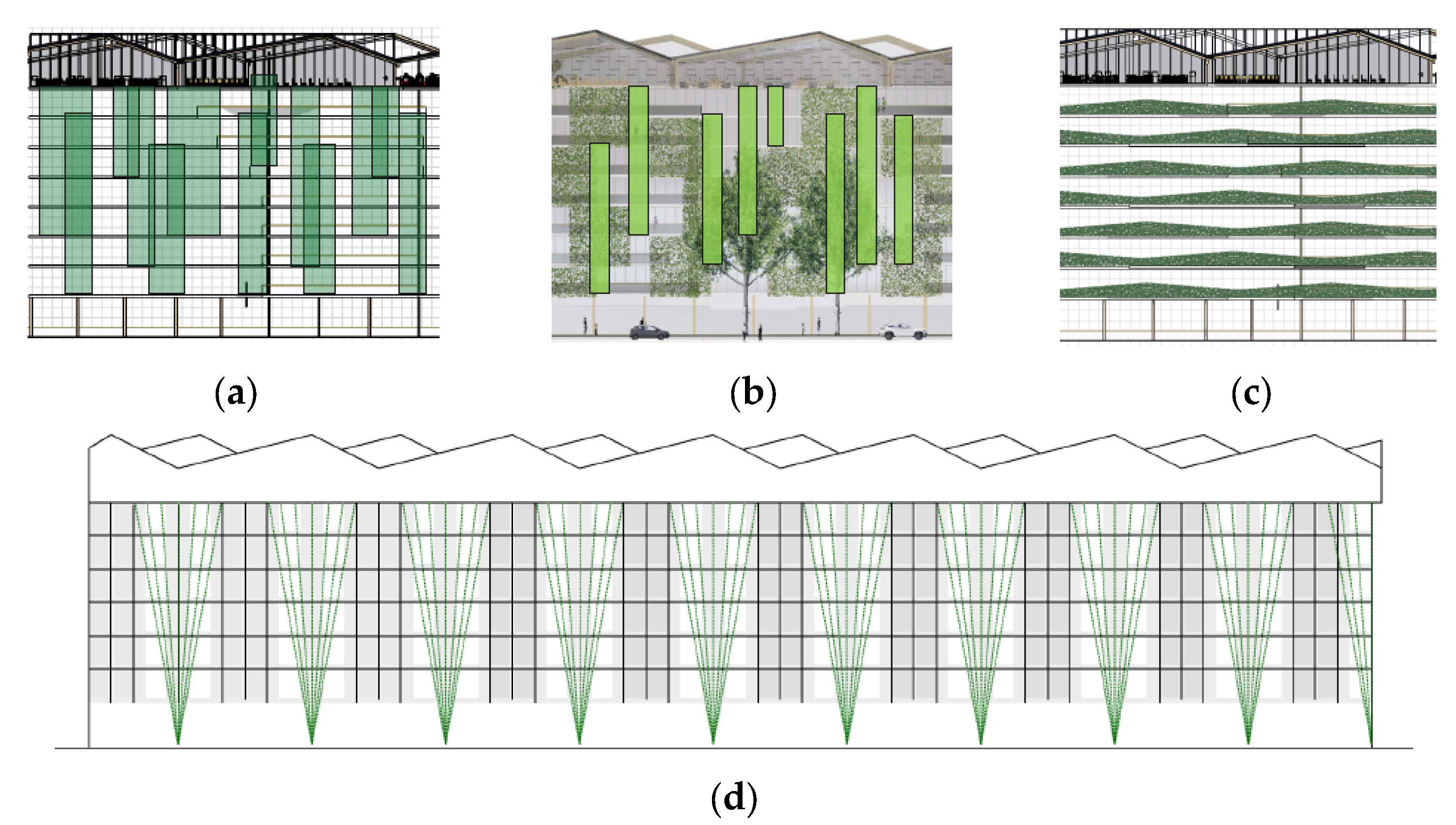

3.2.2. Mosaic

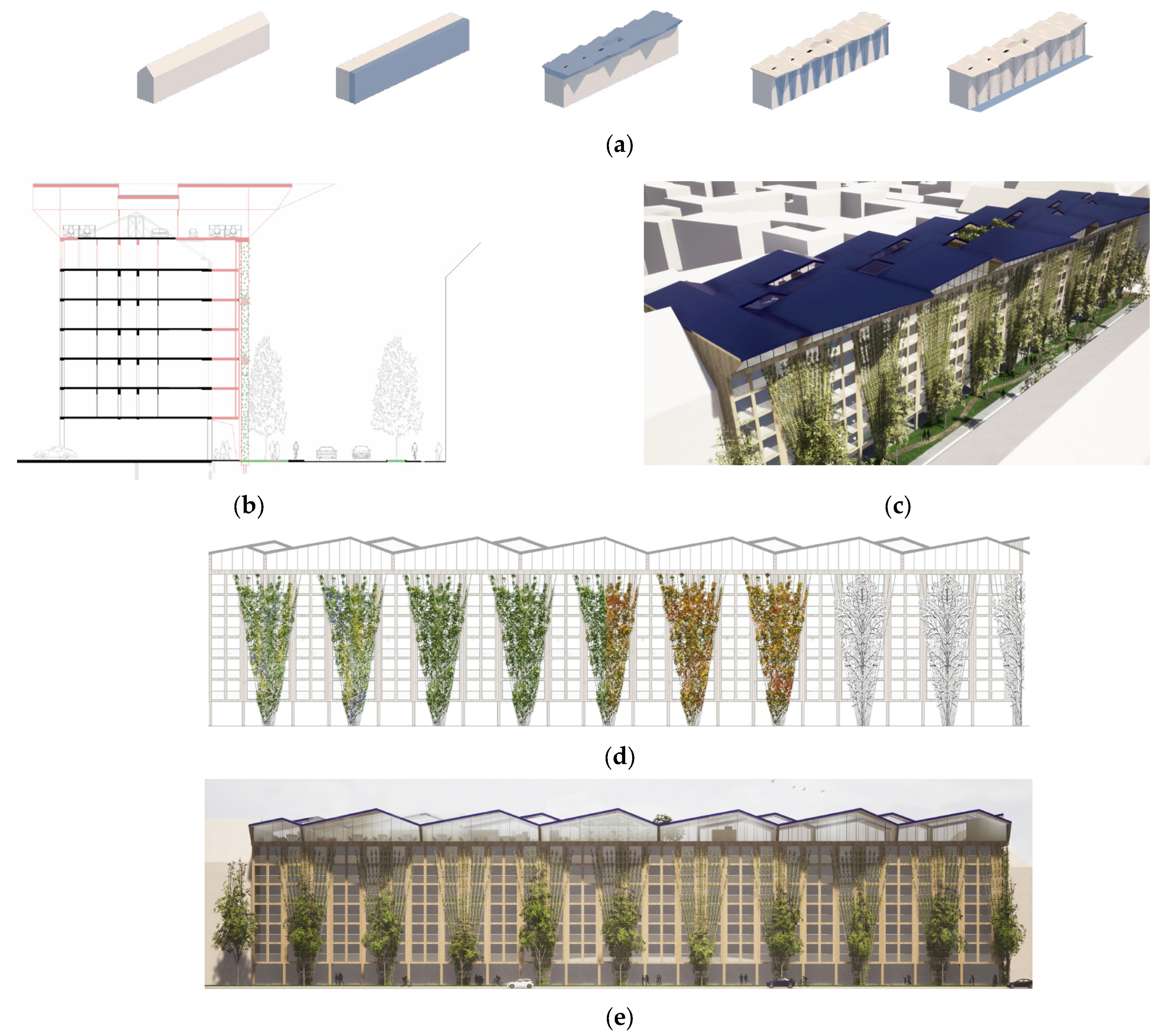

3.2.3. Under the City Roofs

3.3. Post-Design Phase

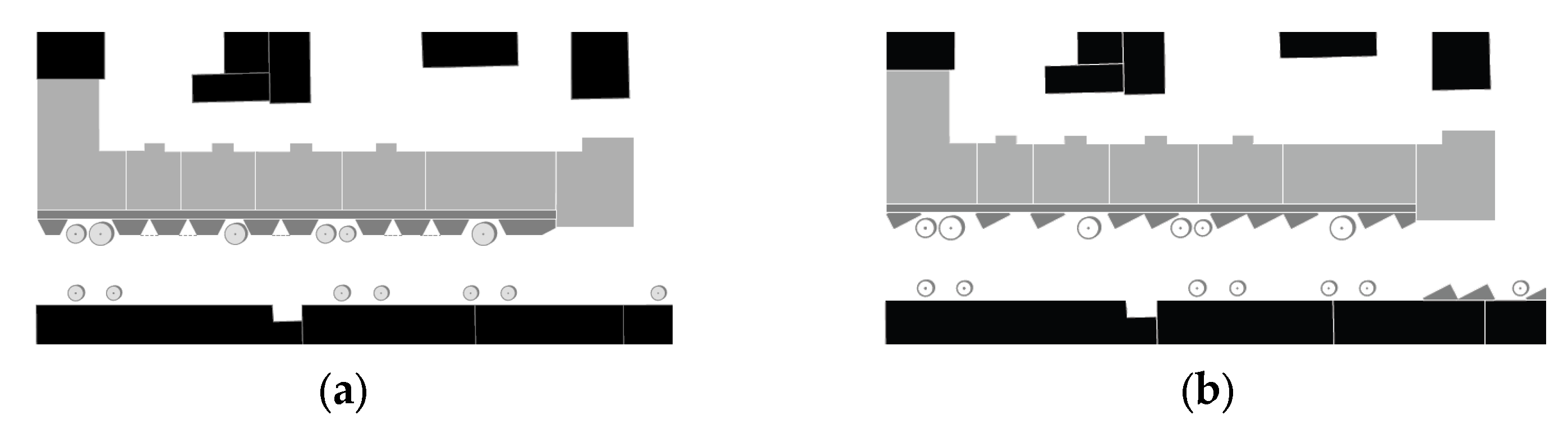

3.3.1. Design Strategies and Transferability

- Modular kit for districts

- Enlarging active façade areas

- Enlarge active roof areas

3.3.2. Reflections on the Design Process within the Design Studio

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Kuttler, W. Klimawandel im urbanen Bereich: Teil 1, Wirkungen. Environ. Sci. Eur. SpringerOpen J. 2011, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brasche, J.; Hausladen, G.; Maderspacher, J.; Schelle, R.; Zölch, T. Zentrum Stadtnatur und Klimaanpassung: Teilprojekt 1: Klimaschutz und Grüne Infrastruktur in der Stadt; Abschlussbericht, Referat Klimapolitik, Klimaforschung; Bayerisches Staatsministerium: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chemisana, D.; Lamnatou, C. Photovoltaic-green roofs: An experimental evaluation of system performance. Appl. Energy 2014, 119, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.M.; Chan, S.C. Integration of green roof and solar photovoltaic systems. In Proceedings of the Joint Symposium 2011: Integrated Building Design in the New Era of Sustainability, Hong Kong, 22 November 2011; pp. 1.1–1.10. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, M.; Schmidt, M.; Laar, M.; Wachsmann, U.; Krauter, S. Photovoltaic panels on greened roofs: Positive interaction between two elements of sustainable architecture. In Proceedings of the RIO 02—World Climate & Energy Event, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 6–11 January 2002; pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Penaranda Moren, M.S.; Korjenic, A. Green buffer space influences on the temperature of photovoltaic modules: Multifunctional system: Building greening and photovoltaic. Energy Build. 2017, 146, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggimann, S.; Wagner, M.; Ho, Y.N.; Züger, M.; Schneider, U.; Orehounig, K. Geospatial simulation of urban neighbourhood densification potentials. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, M.; Dettmar, J.; Martin, A. UrbanReNet: EnEFF:Stadt—Verbundprojekt Netzoptimierung—Teilprojekt: Vernetzte Regenerative Energiekonzepte im Siedlungs- und Landschaftsraum; Technische Universität Darmstadt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender, E.; Hemmerle, C.; Rohrbach, A. Solar and green strategies for the redevelopment of urban districts. In Proceedings of the 16th Advanced Building Skins Conference & Expo, Bern, Switzerland, 21–22 October 2021; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Grundlagen Für Eine Klimawandelangepasste Stadt- und Freiraumplanung; Wende, W. (Ed.) Rhombos: Berlin, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783944101156. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, D. Stadtklimaanalyse Landeshauptstadt München; GEO_NET Umweltconsulting GmbH: Hannover, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loga, T.; Stein, B.; Diefenbach, N.; Born, R. Deutsche Wohngebäudetypologie: Beispielhafte Maßnahmen zur Verbesserung der Energieeffizienz von Typischen Wohngebäuden; IWU: Darmstadt, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783941140479. [Google Scholar]

- Heinstein, P.; Ballif, C.; Perret-Aebi, L.-E. Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV): Review, Potentials, Barriers and Myths. Green 2013, 3, 125–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M. Green facades—A view back and some visions. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuperlach ist Schön: Zum 50. Einer Gebauten Utopie; Hild, A.; Müsseler, A. (Eds.) 1. Auflage; Franz Schiermeier Verlag: München, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-943866-65-0.

- Semprini, G.; Gulli, R.; Ferrante, A. Deep regeneration vs shallow renovation to achieve nearly Zero Energy in existing buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 156, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E.; Delera, A.C. Enhancing the Historic Public Social Housing through a User-Centered Design-Driven Approach. Buildings 2020, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlwein, S.; Pauleit, S. Trade-Offs between Urban Green Space and Densification: Balancing Outdoor Thermal Comfort, Mobility, and Housing Demand. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguacil, S.; Lufkin, S.; Rey, E. Architectural Design Scenarios with Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Solutions in Renovation Processes: Case Study in Neuchâtel (Switzerland); PLEA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, C.; Maturi, L.; Scognamiglio, A.; Frontini, F.; Munari Probst, M.C.; Wall, M.; Roecker, C. Designing Photovoltaic Systems for Architectural Integration: Criteria and Guidelines for Product and System Developers; Report T.41.A.3/2: IEA SHC Task 41 Solar Energy and Architecture; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, L. Warum Forschendes Lernen Nötig und Möglich Ist; UVW Universitätsverlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, T.J. 5m: Baulinienverschiebung als Nachverdichtungsstrategie. Master’s Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Research by Design: Proposition for a Methodological Approach. Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, F.; Ludwig, F. Development of an Integrated Design Strategy for Blue-Green Architecture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauberg, J. Research by design—a research strategy. Archit. Educ. J. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rueß, J.; Gess, C.; Deicke, W. Forschendes Lernen und forschungsbezogene Lehre—Empirisch gestützte Systematisierung des Forschungsbezugs hochschulischer Lehre // Forschendes Lernen und forschungsbezogene Lehre—Empirisch gestützte Systematisierung des Forschungsbezugs hochschulischer Lehre. ZFHE 2016, 11, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, B. LowEx-Bestand Analyse: Systematische Analyse von Mehrfamilien-Bestandsgebäuden; Karlsuher Institut für Technologie (KIT): Karlsruhe, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC, 1. publ; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-107-02506-6.

- Brears, R.C. Blue and Green Cities: The Role of Blue-Green Infrastructure in Managing Urban Water Resources; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-137-59257-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnatou, C.; Chemisana, D. A critical analysis of factors affecting photovoltaic-green roof performance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfoser, N.; Jenner, N.; Henrich, J.; Heusinger, J.; Weber, S. Gebäude Begrünung Energie: Potenziale und Wechselwirkungen: Interdisziplinärer Leitfaden als Planungshilfe zur Nutzung energetischer, klimatischer und gestalterischer Potenziale sowie zu den Wechselwirkungen von Gebäude, Bauwerksbegrünung und Gebäudeumfeld. 2013. Available online: https://www.baufachinformation.de/literatur.jsp?bu=2013109006683 (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Munari Probst, M.C.; Roecker, C. Criteria for Architectural Integration of Active Solar Systems IEA Task 41, Subtask A. Energy Procedia 2012, 30, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penaranda Moren, M.S.; Korjenic, A. Hotter and colder—How Do Photovoltaics and Greening Impact Exterior Facade Temperatures: The synergies of a Multifunctional System. Energy Build. 2017, 147, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Hypothesis | Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| PV mainstreaming design | Applying PV to areas with maximum solar irradiation according to shading studies and greenery to all other areas creates specific local façade layouts and an effective resolution for climate protection and adaptation conflicts. | Shading should not be a knock-out criterion for inner-city façades where solar exposure is limited in any case, and architectural criteria should have priority. ⟶Balancing of design decisions according to individual priorities instead of the general evaluation of solar potential. ⟶Questioning yield-oriented design. |

| Use of (close to) standard PV modules | Gradually transparent PV modules can be replaced by (moveable) PV shutters, thus providing flexible shading while entailing lower costs and planning efforts. | Enhanced feasibility and functionality of large-scale module design. |

| Partially transparent PV modules can be replaced by a combination of transparent glazing and opaque PV areas, thus leading to lower costs and lower overheating risks. | Enhanced feasibility and functionality due to application of standard PV. | |

| Low investment costs of (close to) standard PV modules allow for the economically reasonable application of PV in non-ideal orientations. | Economies of scale compensate for reduced energy yield. ⟶Questioning yield-oriented design. | |

| Architectural design of PV modules’ backsides | The adaptability of PV modules enhances social acceptance. | Residents are sensitive to interventions in their private surroundings. ⟶A comfortable visual ambience enhances the acceptance of PV. |

| Simple, robust, participative green | Simple and robust greenery systems simplify their application while entailing lower maintenance efforts and costs. | Enhanced feasibility and functionality of robust greenery systems. |

| Compostable greenery systems entail lower embodied energy than sophisticated living wall systems. | Reduction of the carbon footprint of compostable vertical greenery systems. | |

| Individual choice of plants (and eventually its maintenance) enhances social acceptance. | The participative, voluntary, and customized integration of greenery provides identification. | |

| Creation of accessible roof gardens | Accessible roof gardens provide semi-public open spaces and recreation areas for residents (social benefits). | Shared roof gardens strengthen the feeling of community among residents. |

| Enhance cooling by water running through façade greenery | Constant irrigation of vertical greenery systems increases the evapotranspiration rate. | Improved cooling performance but high water demand and constructively complex layout leads to high costs. ⟶High effort resulting in small microclimatic effects. |

| Redensifying green infrastructure | Additional street trees can fill the gaps between existing ones. | Street trees provide a significantly larger amount of green volume compared to vertical greenery systems. |

| Greening of glass façades improves the microclimate for street trees. | Vertical greenery systems in front of glazing reduce disturbing reflections. | |

| Economic balancing of PV and green | High costs per m2 (compared to PV modules) require the deliberate placing of vertical greenery systems. | The deliberate, punctual use of façade greenery generates benefits while providing affordable solutions but may be questioned in favour of design considerations. |

| Temporary solutions for growth period of façade greenery | Removable plant troughs can bridge the time span of 10–12 years until climbing plants reach the roof. | Intermediate greenery solutions achieve quick and efficient vegetation of façade with immediately high architectural quality. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fassbender, E.; Ludwig, F.; Hild, A.; Auer, T.; Hemmerle, C. Designing Transformation: Negotiating Solar and Green Strategies for the Sustainable Densification of Urban Neighbourhoods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063438

Fassbender E, Ludwig F, Hild A, Auer T, Hemmerle C. Designing Transformation: Negotiating Solar and Green Strategies for the Sustainable Densification of Urban Neighbourhoods. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063438

Chicago/Turabian StyleFassbender, Elisabeth, Ferdinand Ludwig, Andreas Hild, Thomas Auer, and Claudia Hemmerle. 2022. "Designing Transformation: Negotiating Solar and Green Strategies for the Sustainable Densification of Urban Neighbourhoods" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063438

APA StyleFassbender, E., Ludwig, F., Hild, A., Auer, T., & Hemmerle, C. (2022). Designing Transformation: Negotiating Solar and Green Strategies for the Sustainable Densification of Urban Neighbourhoods. Sustainability, 14(6), 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063438