Abstract

Maladaptive and problematic buying/shopping has been the subject of a considerable amount of research over the last few decades. This research exploited the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) theory to evaluate the mediating effects of online interpersonal relationships and data ownership awareness on the relationship between consumers’ perceived benefit of online shopping and problematic internet shopping behavior. A total of 409 internet shoppers participated in this study. The authors performed all the analyses using the statistical package SPSS. The bootstrapping method used parallel and serial mediation models to assess whether OIR and DOA mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS. The analysis results indicate that PBOS has a negative influence on PIS. In addition, OIR and DOA sequentially and partly mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS. Pairwise comparisons amongst the three indirect effects suggest that OIR affects the PBOS-PIS relationship more than the other two effects. These results furnish substantial contributions that may advance a coherent theoretical framework on the pathways in which OIR and DOA may influence problematic internet shopping. Limitations of the current study and the implications of these findings are delineated.

1. Introduction

The availability of online shopping and the convenience of having purchases accomplished without face-to-face interaction facilitates the migration of problematic conventional shopping habits to the online environment and results in the development and maintenance of problematic internet shopping [,,]. There has been a wide variety of terms introduced to characterize problematic buying–shopping, including compulsive buying [,], buying–shopping disorder [,], pathological buying [,], and shopping addiction [,,], to name a few. Compulsive buying has been used to portray an individual’s inability to control their excessive purchases [] or refers to chronic, repetitive, and problematic behavior in which individuals fail to regulate their impulsive buying habits []. While clinical psychology and psychiatry literature refers to compulsive buying as a behavioral addiction [] or a disorder of impulse control [], it is, however, considered to be an “irrational way of purchasing” from the perspective of consumer behavior and marketing literature []. Likewise, disorders emerging from internet shopping have been proposed, including online shopping addiction [,], online compulsive buying [], or pathological buying online []. In the current study, in line with [,], we prefer to use the term “problematic internet shopping”, as it seems to be more neutral than other derivatives given to this transitioning phenomenon.

Prior research has indicated that individual and contextual factors can influence problematic buying/shopping. Potential risk factors of compulsive buying include extraversion, neuroticism, materialism, stress, depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, low self-control, and poor self-efficacy [,]. Moreover, a strong relationship is revealed between compulsive buying and deficient self-regulation and self-control, along with an inability to confront negative emotions efficiently [,]. Meanwhile, contextual factors include parents and peer influence, social influence, social support, and media exposure []. Together, these factors might play a crucial role in shaping an individual’s problematic behavior toward online shopping []. The influence of these factors is further supported by the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) model, which determined the effect of the environmental stimulus and emotional response on individuals’ behavior [].

Online communities facilitate interaction among individuals with a shared interest to initiate new, maintain existing, and foster impaired interpersonal relationships. The notion of self-disclosure reflects a social process of revealing personal information with another, including thoughts, feelings, and experiences in an interpersonal relationship []. Self-disclosure has been proposed to significantly contribute to interpersonal relationships, stimulating the enhancement of liking, understanding, and intimacy []. Consumers can easily interact and exchange shopping experiences with others in the online shopping environment and ultimately acquire efficient purchasing decisions. Consequently, online interpersonal relationships and reference groups have become influential factors for consumers’ purchase intentions. When consumers consider whether or not to purchase a product, they will readily rely on their reference group’s attitudes and value orientations []. However, there are inconclusive results regarding the effective mechanism of online interpersonal interaction as it affects purchase intention.

In the context of big data, the capability of businesses to accumulate and analyze large sets of consumer data has initiated new sources of the market-based competitive edge []. However, a surge in the collection and manipulation of consumer data, incredibly personal and sensitive data, has increased apprehension regarding the misuse and the invasion of privacy caused by these practices. Although people are increasingly aware of the value of data and the manners in which firms collect and process their data [], they still tend to relinquish some of their privacy protection in exchange for tailored products and services. Prior studies showed the discrepancy between users’ awareness and privacy apprehension and their existent behavior online, a phenomenon that has been described in the literature as the privacy paradox [,]. Individuals may become consciously and unconsciously unaware of the possibility that their data may be misused or compromised, often without much-deliberated control. In this regard, data ownership has juridically been defined as the legal right to mandate information approach, use, and dissemination []. Additionally, a positive association between information ownership rights and control has been revealed []. Therefore, the topic of data ownership is relevant, particularly in the big data era, where consumers divulge a mounting volume of information, while companies harness this information to enhance existing operations. However, much less is revealed about the relationship between interpersonal communication and privacy []. Indeed, the extent to which perceived benefit impacts problematic internet shopping and whether online interpersonal relationships and data ownership awareness influence problematic internet shopping remains unexplored. Therefore, the present study delves into this association and examines the mediating role of online interpersonal relationships (OIR) and data ownership awareness (DOA) in the relationship between the perceived benefit of online shopping (PBOS) and problematic internet shopping (PIS).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

The stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) model explains the impact of an environmental stimulus and emotional response on individuals’ behavior. Prior research has employed the S-O-R model to examine individuals’ impulsive consumption behavior. Accordingly, various online environmental stimuli influence customers’ cognitive and affective organism processes, consequently formulating the user’s behavioral responses []. In an online shopping context, the stimulus corresponds to triggers or cues in the online setting that influences consumers’ affective experiences (e.g., the appearance of the e-retail stores). Organism represents the inward state of customers’ emotions and cognition when interacting with the stimuli, whereas response manifests customers’ impulsive shopping behavior as reactions toward the stimulus and their internal evaluation, such as purchase intentions []. Impulsive buying is defined as unintentional and abrupt purchase behavior, often triggered by the shopping environment. According to Kyrios et al. [], impulsive buying is a less pronounced manifestation of compulsive buying wherein the former represents the initial stage and the latter represents the extreme boundary of the same behavior []. We consider the S-O-R framework to be a sound theoretical foundation for the present study. Accordingly, we postulate stimulus to be e-commerce advantages driven by advanced data-driven technologies, the organism to be consumer-to-consumer and consumer-to-system interactions manifested by OIR and consumers’ DOA, and response to be undesirable behavioral consequences of excessive, impulsive, and compulsive shopping online (i.e., problematic internet shopping).

2.2. Perceived Benefits of Online Shopping

Perceived benefits in the online shopping context represent the combination of advantages that meet a user’s expectation [] or a consumer’s belief about the extent to which they will become affluent from purchasing online with a particular website []. Previous studies by Forsythe et al. [] highlighted that convenience, product selection, ease of shopping, and enjoyment are essential perceived benefits customers obtain from online shopping [,]. In addition, big data analytics has enabled customers to acquire relevant information about the products of interest and quickly purchase them through the support of improved search engines and recommendation systems without any constraints []. Online shopping provides unending possibilities for efficient goal-directed information search, price comparisons, and convenient purchasing of a wide variety of products []. Moreover, e-commerce websites integrate features designed to enhance consumer-to-consumer and customers-to-brand communication and provide timely support and information resources concerning products of interest. Those advantages result in instant gratification or relief from negative feelings, which, in turn, significantly affect consumers’ attitudes toward online shopping [] and online shopping behavior [,]. Likewise, some anecdotal evidence indicates e-commerce incorporates features that have heightened online compulsive buying [,,].

2.3. Online Interpersonal Relationships

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, the notion of interpersonal relationships “encompasses social interactions, connections, or affiliations, especially ones that are socially and emotionally significant, between two or more people”. The capability to attach to and constitute ongoing intimate relationships with other people is a distinctive attribute of the human experience. However, whether Internet use enhances or wears down interpersonal relationships has been the subject of considerable controversies. Proponents of the Internet contended its possibilities for making new friends, maintaining interpersonal relations [,,], and gaining social capital [,], while the skeptics oppose this optimistic viewpoint [,]. These inconclusive findings may partly stem from examining the Internet as a single facet [,], the changes to the Internet, and how people use the Internet [,]. Internet shopping provides an essential social support system for the relatively introverted or those who have few friends []. Such concealed social support enables users to satisfy their needs through purchasing []. According to attachment theory, a deficit of interpersonal relationships may jeopardize an individual’s sense of security, triggering problematic behaviors []. More specifically, inferior interpersonal relationships were a detrimental consequence of compulsive buying [], whereas heightened interpersonal conflict was more relevant to abnormal spending behavior and a preoccupation that denotes compulsive buying [].

2.4. Data Ownership Awareness

To date, there is still no agreed-upon definition of the term that entirely covers the issue of data ownership. The uncertainty and absence of clear regulations relating to data ownership [] mean that the question of data ownership (i.e., who should own the data) remains without a conclusive answer. Data ownership is considered to be “the possession of complete control over the data and its rights including, but not limited to access, creation, generation, modification, analysis, use, sell, or deletion of the data, in addition to the right to grant rights over the data to others” []. Companies have leveraged the ability to collect, store, disseminate, and manipulate massive amounts of consumer information to remain competitive in a progressively knowledge-based society []. The rising amount of data is undoubtedly provoking the issue of data ownership. However, there has been very little academic inquiry into consumer data ownership and management issues relating to the data that companies routinely collect for marketing-related purposes. The dearth of transparency regarding data collection introduces more complexity when trying to figure out what happens to consumers’ data—i.e., how it is stored, processed, or disseminated to other parties. This increasing tendency underscores the necessity to obtain control over the manipulation and accessibility of these data. Existing literature from a juridical perspective suggested that data ownership is predominantly associated with the privacy of the individual []. According to Jagadish et al. [], privacy is one aspect of data ownership wherein the former, within the firm–consumers relationship reflects “the extent to which a consumer is aware of and can control the collection, storage, and use of personal information by a firm” []. More specifically, the involvement of different entities who have authorized access to such data, often without prior consent from the data subject [], accrues more complexity to the concept of data ownership [].

According to Rogers’ theory of the adoption of innovation [], awareness is the first step in a five-step procedure for decision making, which includes awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption. In the first step, an individual is exposed to an idea or innovation but lacks information about that idea/innovation and is less likely to seek more information about the idea/innovation. People must first be aware of the ideas and determine whether they are worth adopting before proceeding further. Given that the issue of data ownership is multifaceted, encompassing legal, ethical, and technological considerations, we argue that data ownership awareness is the extent to which an individual is conscious about the existence of associated legitimate rights and control measures that they are entitled to and exert toward their digital data. We argue that only when people are fully aware of data ownership will their attitude be shaped.

2.5. Problematic Internet Shopping

Problematic internet shopping refers to “…a tendency of excessive, compulsive, and problematic shopping behavior via the Internet that results in consequences associated with economic, social, and emotional problems” []. The growth of the e-commerce market and excessive buying/shopping may place an individual at an increased susceptibility of perpetual behaviors crossing some thresholds and becoming problematic. According to Koufaris [], greater anonymity, unhindered access to the international marketplace, and a pronounced likelihood of hiding purchases from their tight-knit connections can stimulate a buyer to make purchases repeatedly, resulting in unplanned shopping. Furthermore, enticing sales, attractive in-store arrangements, and convenient payment methods could constitute a key trigger for problematic internet shopping [,,]. In a similar vein, over-exposure to online advertisements and embedded marketing strategies have been reported to elevate the risk of problematic internet shopping []. Therefore, it is intuitively convincing to speculate that traditional problematic shopping can migrate into the online environment and result in problematic internet shopping, which might eventually deteriorate affected an individual’s social life and economic and psychological condition [,]. From the sociological perspective, the subject of addiction is not the material good but the interaction between an affected individual and their context-specific addiction subject []. Therefore, seamless access to all goods and services online without constraints manifests a fertile ground for developing problematic internet shopping [,].

2.6. Research Model

The current study sets out to examine the potential intermediating role of OIR and DOA on the association between PBOS and PIS. The extant literature has started to focus on the relationships of PBOS with consumer attitude and online purchasing behavior, yet no study has ever considered the relationship with problematic internet shopping. In addition, the degree to which OIR and DOA mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS remains unexplored. However, several pieces of indirect evidence have supported this association. Firstly, endeavors have been dedicated to scrutinizing the mediating roles of interpersonal relations in the association between psychological factors and internet addictive behaviors [,,]. For example, the interpersonal relationship was a protective factor against smartphone addiction and partially mediated the relationship between stress and problematic smartphone use []. In the same vein, Ryu et al. [] revealed a fully mediating effect of interpersonal relationships on the linkage between impulsivity and people diagnosed with internet gaming disorders. Secondly, the association between privacy and social capital in a social networking site context is reported []. Scholars have demonstrated the close relationship between privacy and disclosures, emphasizing the complex privacy–disclosure trade-off in people’s intention to disclose information []. Self-disclosure is identified as a precondition for the establishment of interpersonal relationships. Kwak, Choi, and Lee [] argue that self-disclosure behavior seemingly and positively alters the scale and intimacy of interpersonal relationships. Similarly, the linkage between self-disclosure and social support is documented [], highlighting the direct compensation of social support in return for sharing and disclosing information. Lastly, the existing scholarly research has revealed the essential role of parents and peers in shaping individuals’ engagement or avoiding risky behavior by balancing risks and benefits [,]. For instance, online social support was positively related to internet addiction seriousness [,]. Thus far, no research has scrutinized the proposed relationships among PBOS, OIR, DOA, and PIS. We, therefore, contend that examining the mediation effect of OIR and DOA can better elucidate the complex intervening mechanism of how consumers’ perceptions are associated with problematic internet shopping.

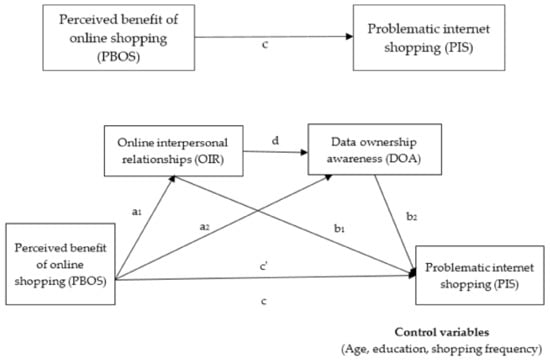

To better understand the mechanisms guiding the relationship between PBOS and PIS, we proposed multiple mediation models, including parallel and sequential mediation, to simultaneously explore how PBOS influences PIS []. Unlike the parallel mediation model, where there is no causal influence among mediators, such an assumption is not available in the serial mediation model, and we can, thus, test a specific theoretical sequence among the variables. To this end, we set up a mediation model in which OIR and DOA are proposed to mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS. The exploration of variable ordering provides improved evaluation, reveals the prospect of the constructs, and suggests new postulates for relationships of interest, which finally advance theory and practice. We expected that the indirect effects of OIR and DOA would significantly account for the relationship between PBOS and PIS. We also hypothesized that the order of the variables would matter, such that OIR precedes DOA in a serial mediation model (Figure 1). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Figure 1.

Hypothesized serial mediation model linking PBOS and PIS.

Hypothesis 1. (H1) (a1b1).

Online interpersonal relationships (OIR) mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS.

Hypothesis 2. (H2) (a2b2).

Data ownership awareness (DOA) mediates the relationship between PBOS and PIS.

Hypothesis 3. (H3) (a1db2).

The association between PBOS and PIS is sequentially mediated by online interpersonal relationships and data ownership awareness.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

A non-clinical sample incorporating 409 respondents (mean age = 35.42 ± 11.24 years, range 21–70 years; 34.47 percent female) was conveniently recruited online. We administered a battery of self-reported questionnaires from October to November 2020. Potential internet shoppers who had participated or been involved in any online buying–shopping activities (i.e., reading online reviews, gathering information for specific brands, comparing the price across online retail stores, and making a purchase) over their last twelve months were deemed to be eligible to participate in our survey. Respondents were notified of the details of the study and agreed to give their informed consent afterward. Before collecting the data, the correspondent author’s institution ethics committee granted the necessary permission for the survey to comply with the Helsinki declaration. Table 1 summarizes the demographic information of the sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. The Scale for Measuring Perceived Benefits of Online Shopping

The operationalization of PBOS was achieved using a 16-item construct adapted from Le and Liaw [] to evaluate the perception of consumers of online shopping’s benefits. Accordingly, we assess the perceived benefit of online shopping based on four dimensions—i.e., (i) information search (4 items), (ii) recommendation system (4 items), (iii) dynamic pricing (4 items), and (iv) customer service (4 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Higher scores indicate a greater perception of online shopping advantages. The internal reliability of the questionnaire was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and resulted in the value of 0.900, indicating high reliability.

3.2.2. The Scale of Online Interpersonal Relationships

The scale measuring online interpersonal relationships consists of 16 questions, adapted from the short version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems 32 (IIP-32) created by Barkham and Hardy [], which tapped into the complications individuals confront in their interpersonal relationships. We simplified and excluded all irrelevant items and reworded all remaining items that refer to online acquaintances ascribed to virtual connections. Respondents rated their responses using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores are indicative of a greater degree of online interpersonal relationships. Two indicators—i.e., OIR3 and OIR8—were excluded from subsequent analysis due to exposing low factor loadings during exploratory factor analysis. All remaining items of the construct achieved high reliability, as indicated by the value of Cronbach’s alpha (i.e., 0.842).

3.2.3. The Scale of Data Ownership Awareness

The scale is designed from existing literature and is used to examine consumers’ awareness of data ownership. Respondents rated the degree to which they are aware of the legitimate rights (e.g., “I am fully aware of having the right to enforce legal action against unauthorized access and exploitation of my online purchasing data”) and the practices that one can exert toward their data (e.g., “I am fully aware of how to control my purchasing data”). The scale comprises eight items, and a five-point Likert scale was adopted for scoring from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”, meaning that higher scores reflect a higher level of awareness. The authors then excluded DO1 and DO7 because they demonstrated low factor loadings. The Cronbach’s alpha of all remaining items was 0.859, indicating the high reliability of the scale.

3.2.4. The Scale of Problematic Internet Shopping

The scale was modified from the Online Shopping Addiction Scale created by Zhao, Tian, and Xin []. Respondents assess 12 items using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher level of PIS. According to Duong and Liaw [], this scale could appropriately evaluate three psychological dimensions of problematic internet shopping: (1) “Obsessive”, including “I cannot stop myself from online shopping temptation”; (2) “Impaired Mood Regulation”, including “I will feel angry or upset because of my inability to shop online.”; (3) “Ramification”, including “My daily obligations get worse because of online shopping”. The internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for all items was 0.940, indicating the high reliability of the scale.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The following procedure reflects the flow of the data analysis. First, we conducted descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Later, we used the PROCESS macro for the SPSS (Model 4) [] to test the mediation effect of OIR and DOA separately. The analysis process is continued by using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 6) [] to analyze a sequential mediation model of OIR and DOA in the relationship between PBOS and PIS. The statistical significance of the indirect effects was assessed using 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confident intervals. According to Preacher and Hayes [], the indirect effect is deemed to be significant if the confidence interval does not contain zero. Research has reported great similarities between the structural equation modeling (SEM) and the regression-based approach using PROCESS for mediation results []. Hence, the authors used the PROCESS macro for the present study due to its simplicity, ease of use, and capability to obtain similar results to SEM. Previous studies have suggested that compulsive buying has a positive association with shopping frequency [,], is negatively related to education [,], and appears to be more salient among younger buyers [,]. We controlled for the effect of age, education, and shopping frequency to isolate each mediator’s indirect effect. This procedure also helps us to eliminate alternative explanations for the findings. All variables were standardized before running statistical analyses to assure statistical comparability.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

About two-thirds of the respondents (65.53 percent) were male and involved in partnership relations. A majority of the respondents were well educated, as indicated by 272 (66.5 percent) of the respondents having bachelor’s degrees and 111 (27.14 percent) having master’s degrees or above, while only 26 (6.36 percent) of the respondents obtained just a high school diploma. As for their online purchasing preferences, a majority (76.77 percent) spent up to USD 500 per month on online purchases, and less than three-fourths (74.82 percent) of the respondents shopped online up to six times a year. These characteristics are significant indicators for online shopping behavior.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Among the hypothesized mediators of PBOS on PIS, DOA had the strongest association with PBOS (0.61 **), followed by the association between OIR and PBOS (0.55 **). There was a positive and significant association between the hypothesized mediators (0.68 **). None of the correlations suggest that multicollinearity would be an issue for the multivariate analyses to follow. The multicollinearity concern is further eliminated as all the VIF values were lower than 3.3 and tolerance values exceeded 0.10 []. In addition, the skewness and kurtosis of variables appear to be within the ±2 normality criteria, indicating that our data are normally distributed [].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables.

Before proceeding to mediation analysis, we conducted a simple linear regression analysis and found that perceived benefit influences problematic internet shopping (b = 0.342, p < 0.001). This result is in accordance with results reported by Mikołajczak-Degrauwe and Brengman [], wherein they argued that a positive attitude towards advertising could lead to compulsive buying. Once a relationship has been established, we will introduce OIR and DOA as a single mediator.

4.2. The Mediating Role of Online Interpersonal Relationships

We used Model 4 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS to assess the mediating effect of OIR on the relationship between PBOS and PIS (H1). We controlled for age and education along with shopping frequency and found a positive association between PBOS and OIR (b = 0.53, p < 0.001), which consequently related to PIS (b = 0.64, p < 0.001). However, the remainder direct relationship was not significant (b = −0.03, p = 0.553). These results suggested that OIR fully mediated the relationship between PBOS and PIS (total indirect effect = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.23 to 0.40). Overall, these results indicate that PBOS was associated with a higher degree of OIR, which, in turn, was positively associated with PIS. This simple mediation model explained 49.40 percent of the variance in problematic internet shopping, supporting H1.

4.3. The Mediating Role of Data Ownership Awareness

We also employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4) to examine the mediating effect of DOA on the association between PBOS and PIS. We controlled for the effects of age, education, and shopping frequency and found that PBOS was positively associated with DOA (b = 0.59, p < 0.001), which was, in turn, significantly associated with PIS (b = 0.56, p < 0.001). Again, the direct effect was not significant (b = −0.02, p = 0.719) which implied that there was a full mediation effect between PBOS and PIS (total indirect effect = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.25 to 0.43) via DOA. Overall, the analysis results suggest that PBOS was associated with a higher degree of DOA, which, in turn, was positively associated with PIS. This model accounted for 41.50% of customers’ problematic online shopping variance, supporting H2.

4.4. The Parallel Mediation Model

Parallel mediation assumes that two mediators mediate the association between an independent and dependent variable with no mediator causally influencing another. The authors performed a parallel mediation analysis to evaluate the simultaneous impact of OIR and DOA on the relationship between PBOS and PIS. We also controlled for the potential contribution of age, education level, and shopping frequency by partially singling them out as covariates. The analysis shows that the indirect effect of PBOS on PIS via OIR was 0.265, with bootstrapped 95% CIs [0.172, 0.375], indicating a significant amount of mediation. Similarly, the indirect effect of PBOS on PIS via DOA was 0.180, with bootstrapped 95% CIs [0.103, 0.261], stipulating a significant amount of mediation. The residual direct effect was also significant (b = −0.127, p = 0.004), indicating a significant partial mediation. Therefore, OIR and DOA partially mediated the effects of PBOS on PIS. Overall, PBOS positively influences PIS (b = 0.317, t = 7.186, p < 0.001), and OIR exerts a stronger mediation effect than DOA, as indicated by the specific indirect contrast.

4.5. The Serial Mediation Model

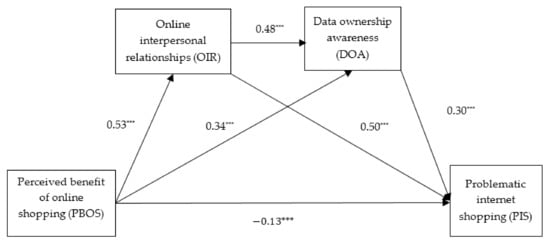

Serial mediation assumes a causal chain linking OIR and DOA with a specified direction flow. We employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 6) to examine the sequential mediating effects of OIR and DOA on the relationship between PBOS and PIS. Data presented in Figure 2 and Table 3 demonstrate that all the pathways were significant after controlling for the covariates. First, the indirect effect of “PBOS → OIR → PIS” was significant (indirect effect = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.17 to 0.37). Second, the indirect effect of “PBOS → DOA → PIS” was also significant (indirect effect = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.16). Therefore, OIR and DOA simultaneously mediated the association between PBOS and PIS. Furthermore, the serial pathway “PBOS → OIR → DOA → PIS” was significant (indirect effect = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.13), implying that a more positive perception about the benefits of online shopping (PBOS) was serially associated with higher online interpersonal relationships (b = 0.53, p < 0.001), higher data ownership awareness (b = 0.48, p< 0.001), and finally more problematic internet shopping (b = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

The results of the sequential mediation model. *** p < 0.001. Control variables: age, education, and shopping frequency.

Table 3.

Summary of the direct and indirect pathways of the serial mediation model.

The direct pathway “PBOS → PIS” was also significant (b = −0.13, p < 0.01). Hence, OIR and DOA partially mediated the association between PBOS and PIS. Overall, this serial mediation model explained significant variance in consumer problematic internet shopping (R2 = 0.535). This R-squared value surpasses the prescribed cut-off threshold of 0.4 [] and denotes the high explanatory power of the model. Results in Table 3 show that OIR and DOA partially mediated the relationship between PBOS and PIS in sequence. In sum, the analysis results show that PBOS is associated with higher OIR and DOA, which relate to higher levels of PIS. Thus, H3 is also supported.

We then performed pairwise comparisons among the three indirect effects to observe the strength of these associations on the PBOS-PIS relationship. The analysis suggest that the indirect effect of PBOS on PIS through OIR was significantly greater than the indirect effect through DOA (b = 0.16, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.31) and that of the serial mediating model (b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.08 to 0.31). The pairwise comparison between the serial mediating effect and the indirect effect through DOA was not statistically significant (b = 0.02, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = −0.05 to 0.09). Overall, the results shed light on the relationship between PBOS and PIS by providing empirical evidence that OIR plays a more critical role than DOA, although both factors impact the relationship.

Our analysis results indicated that age and education are significant predictors of problematic internet shopping as the control variables. Specifically, age was found to negatively affect endogenous variables (b= −0.01, p < 0.01). Likewise, education positively and significantly influences problematic internet shopping (b = 0.24, p < 0.001). These results suggest that more highly educated and younger individuals are more prone to problematic internet shopping, aligning with previous investigations [,].

To further clarify the direction of the indirect effect, we also tested an alternative model in which DOA preceded OIR. Results indicated that the indirect path (Ind3) remained significant, but the effect was more potent than that of the inverse sequence (indirect effect coefficient =0.155, SE = 0.027, 95% CI = 0.018, 0.212).

5. Discussion

The current study sets out to examine the mediating effect of OIR and DOA in the relationship between PBOS and PIS. The analysis results reveal the serial mediating effects of OIR and DOA on the linkage between PBOS and PIS, advancing our understanding of how consumer perceptions relating to the benefit of online shopping are associated with PIS.

The study results demonstrate that PBOS impacted PIS directly and indirectly via OIR and DOA. The most pronounced finding of the current research is that PBOS had initially and solely exerted a positive impact on PIS. However, the introduction of OIR and DOA into the mediation model alters the sign and magnitude of the effect. Specifically, the parallel and serial mediation models suggest that PBOS has a significant but negative impact on PIS. One probable reason for this phenomenon is that the initial positive direct impact has completely been transferred through or lessened by two mediators. Another feasible explanation is that consumers’ perceptions of the benefits of online shopping may be associated with a positive attitude toward internet purchasing but may not necessarily result in PIS. These findings signify the profound impacts of other factors’ influence on PIS. For instance, the potential disadvantages consumers suffer from online purchasing can obliterate the benefits and impede consumers’ problematic internet shopping. Therefore, future research is needed to provide empirical evidence for this speculation.

Our results further indicated that OIR partially accounted for the relationship between PBOS and PIS. To our knowledge, this is the first effort to examine the mediating role of OIR in the association between PBOS and PIS. We found a positive association between OIR and PIS, indicating that online interpersonal relationships seemingly induce PIS as consumers rely on online social support for improved decisions. Prior research has recognized the influence of peers, reference groups, and the use of e-WOM on online purchase intentions [,,]. Singh and Nayak [] suggested that an individuals’ interpersonal relationships determine the compulsivity levels. Moreover, peer communication results in the pressure of reference groups, which becomes a driver of compulsive buying, with those who aspire to become a member of the given peer groups particularly susceptible [,]. This finding is consistent with prior investigations [,,] reporting a positive association between interpersonal relationships, online social support, and internet addictive behaviors.

The mediation analysis results demonstrate that DOA significantly mediates the relationship between PBOS and PIS. This finding indicates that people who perceive more advantages of online shopping are more likely to be aware of data ownership, thereby increasing the susceptibility of problematic internet shopping. Our results also revealed a positive impact of OIR on DOA, indicating that individuals with greater OIR are more likely to be aware of data ownership. Superior interpersonal relationships generate more opportunities for users to participate and communicate in online consumer communities. Therefore, data ownership awareness can be initiated or guided by affective discussions shared by community members. Such interpersonal relations and the increasing exposure of data breaches to public discourse might consequently affect consumers’ data ownership awareness.

This research has several critical theoretical contributions. Prior investigation has employed the S-O-R model to reveal consumer behavior in many contexts. For example, Islam et al. [] utilized the S-O-R model, examining how interpersonal communication contributes to developing social comparisons, which later explains compulsive buying behavior. In the present study, we attempted to apply this theoretical model for PIS by considering PBOS as stimuli, OIR and DOA as the organism, and PIS as behavioral responses to garner insight into problematic internet shopping behavior. In addition, this research addressed an under-researched topic (i.e., problematic internet shopping). Thus far, there is insufficient comprehension of why people indulge in PIS and the mediating roles of OIR and DOA in such relationships. The present research accentuates the significant mediating role of OIR and DOA in PIS, adding to extant research that has integrated the internet-related factors into the S-O-R framework [].

The advancement of online technologies and the surge of online transactions have become fertile ground in which problematic internet shopping can become increasingly prevalent. Data-driven technologies (e.g., big data analytics) collect consumer preferences, behavior, and user-specific information to identify and categorize clients and dispatch them notifications that match their expectations. It may be efficacious for consumers to be reassured that their data will be collected with informed consent and can only be used for another purpose with their informed consent. It would also be advisable to increase the awareness of individuals regarding their privacy and privacy-jeopardizing risks to enable consumers to make more objective and rational purchasing decisions. In addition, e-businesses or decision-makers could provide timely education programs on adverse consequences associated with PIS. Social intervention campaigns set up by public institutions or consumer advocacy groups are significantly able to assist consumers to become more goal-directed to further prevent PIS. In addition, providing consumers with a strong virtual customer–brand communication channel would also be imperative to hinder PIS.

Furthermore, the findings demonstrate that DOA plays a mediating role in explaining problematic internet shopping. Incongruently with Asswad and Gómez [], we argue that e-commerce platforms should provide mechanisms that give the user complete control and efficient visibility over the data. Once such tools are equipped, the consumer will control the raw data and permit which entity can access the data. For instance, practices promoting awareness, primarily focused on enhancing consumers’ comprehension of data flow, educational and counseling programs, or social campaigns to boost users’ understanding of data ownership [] are beneficial.

The present study contains some limitations, offering avenues for future research. First, the most salient limitation lies in the fact that our sample was collected from an online crowdsourcing platform; hence, generalizing the results to other populations should be performed with caution. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this research may over-or under-estimate mediation effects [] and does not allow us to capture the causal conclusions among variables. Therefore, longitudinal studies are essential in the future to investigate the causal relationships and examine longer-term models of the effect of PBOS, DOA, and OIR on PIS. Finally, because OIR and DOA only partially mediated the impact of PBOS on PIS in this study, research exploration is warranted to examine the effect of other probable intermediating variables (e.g., low self-esteem, loneliness, and depression), thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insight into the associations between PBOS and PIS that may advance a coherent theoretical framework on the pathways in which OIR and DOA may influence PIS.

6. Conclusions

The present study sheds light on the mechanism linking PBOS to PIS among online purchasers. We investigated the mediating role of OIR and DOA to account for how PBOS is related to PIS. Results suggested that OIR and DOA mediate the relationship between PBOS and PIS. Our investigation also found that OIR was a crucial mediating mechanism explaining how PBOS was related to PIS. Our findings highlight the necessity of establishing and refining online interpersonal relationships and raising the awareness of online consumers with deficient data ownership awareness through interventions designed to assist individuals affected by problematic internet shopping. The multiple mediations and serial mediation model provide a deeper insight into how PBOS is related to PIS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-L.D. and S.-Y.L.; methodology, S.-Y.L. and X.-L.D.; software, X.-L.D.; formal analysis, X.-L.D. and S.-Y.L.; investigation, X.-L.D.; resources, X.-L.D. and S.-Y.L.; data curation, X.-L.D. and S.-Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-L.D.; writing—review and editing, X.-L.D. and S.-Y.L.; supervision, S.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the TaiwanICDF for the scholarship. Also, we would like to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their precious and constructive suggestions during the review process. Their willingness to give their time so generously is sincerely appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- LaRose, R.; Eastin, M.S. Is Online Buying out of Control? Electronic Commerce and Consumer Self-Regulation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2002, 46, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.M.; Liaw, S.-Y. Effects of Pros and Cons of Applying Big Data Analytics to Consumers’ Responses in an E-Commerce Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, A.; Brand, M.; Claes, L.; Demetrovics, Z.; de Zwaan, M.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Frost, R.O.; Jimenez-Murcia, S.; Lejoyeux, M.; Steins-Loeber, S.; et al. Buying-shopping disorder—Is there enough evidence to support its inclusion in ICD-11? CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, R.J.; O’guinn, T.C. A clinical screener for compulsive buying. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E.; Pope, H.G.; Smith, J.M.R.; Strakowski, S.M. Compulsive buying: A report of 20 cases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios, M.; Trotzke, P.; Lawrence, L.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Ali, K.; Laskowski, N.M.; Müller, A. Behavioral Neuroscience of Buying-Shopping Disorder: A Review. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 5, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Trotzke, P.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M. The Pathological Buying Screener: Development and Psychometric Properties of a New Screening Instrument for the Assessment of Pathological Buying Symptoms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotzke, P.; Starcke, K.; Müller, A.; Brand, M. Pathological Buying Online as a Specific Form of Internet Addiction: A Model-Based Experimental Investigation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo, H.-Y.; Harvey, N. Effects of shopping addiction on consumer decision-making: Web-based studies in real time. J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, S.; Dhandayudham, A. Towards an understanding of Internet-based problem shopping behaviour: The concept of online shopping addiction and its proposed predictors. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niedermoser, D.W.; Petitjean, S.; Schweinfurth, N.; Wirz, L.; Ankli, V.; Schilling, H.; Zueger, C.; Meyer, M.; Poespodihardjo, R.; Wiesbeck, G. Shopping addiction: A brief review. Pract. Innov. 2021, 6, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.P.; Khanekharab, J. Identity Confusion and Materialism Mediate the Relationship between Excessive Social Network Site Usage and Online Compulsive Buying. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, R.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Baño, M.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Moragas, L.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Aymamí, N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; et al. Compulsive Buying Behavior: Clinical Comparison with Other Behavioral Addictions. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G.; Capetillo-Ponce, J.; Szczygielski, D. Compulsive Buying in Poland. An Empirical Study of People Married or in a Stable Relationship. J. Consum. Policy 2020, 43, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Tian, W.; Xin, T. The Development and Validation of the Online Shopping Addiction Scale. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, L.T.; Lam, M.K. The association between financial literacy and Problematic Internet Shopping in a multinational sample. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 6, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-M.; Roh, S.; Lee, T.K. The Association of Problematic Internet Shopping with Dissociation among South Korean Internet Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G. Compulsive and compensative buying among online shoppers: An empirical study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejoyeux, M.; Weinstein, A. Compulsive Buying. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2010, 36, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, L.; Bijttebier, P.; Eynde, F.V.D.; Mitchell, J.E.; Faber, R.; Zwaan, M.D.; Mueller, A. Emotional reactivity and self-regulation in relation to compulsive buying. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, R.J.; Vohs, K.D. To buy or not to buy: Self-control and self-regulatory failure in purchase behavior. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Davison, R.M. Social Support, Source Credibility, Social Influence, and Impulsive Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeless, L.R. Self-Disclosure and Interpersonal Solidarity: Measurement, Validation, and Relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlega, V.J.; Metts, S.; Sandra, P.; Margulis, S.T. Self-Disclosure; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Lessig, V.P. Students and housewives: Differences in susceptibility to reference group influence. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Aksoy, L.; Bart, Y.; Heinonen, K.; Kabadayi, S.; Ordenes, F.V.; Sigala, M.; Diaz, D.; Theodoulidis, B. Customer engagement in a Big Data world. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datoo, A. Data in the post-GDPR world. Comput. Fraud Secur. 2018, 2018, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.B. A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday 2006, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, P.A.; Horne, D.R.; Horne, D.A. The Privacy Paradox: Personal Information Disclosure Intentions versus Behaviors. J. Consum. Aff. 2007, 41, 100–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.F. Property rights to consumer information: A proposed policy framework for direct marketing. J. Direct Mark. 1997, 11, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Staples, D.S. Exploring Perceptions of Organizational Ownership of Information and Expertise. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosman, L.A. The relationships among need for privacy, loneliness, conversational sensitivity, and interpersonal communication motives. Commun. Rep. 1991, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Benbasat, I.; Cenfetelli, R.T. The nature and consequences of trade-off transparency in the context of recommendation agents. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 38, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.K.H.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, Z.W.Y. The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrios, M.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Ali, K.; Maclean, B.; Moulding, R. Predicting the severity of excessive buying using the Excessive Buying Rating Scale and Compulsive Buying Scale. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2020, 25, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.C.; Moniz, A.I.D.D.S.A.; Caldeira, S.N.; Silva, O.D.L. “Cannot Stop Buying”—Integrative Review on Compulsive Buying. In Perspectives and Trends in Education and Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.I. The relationship between consumer characteristics and attitude toward online shopping. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2003, 21, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.; Liu, C.; Shannon, D.; Gardner, L.C. Development of a scale to measure the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping. J. Interact. Mark. 2006, 20, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. Retailing and shopping on the Internet. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1996, 24, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.; Byrne, A.; Rowley, J. Mobile shopping behaviour: Insights into attitudes, shopping process involvement and location. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Debei, M.M.; Akroush, M.N.; Ashouri, M.I. Consumer attitudes towards online shopping. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 707–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Aggarwal, A. The role of perceived benefits in formation of online shopping attitude among women shoppers in India. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2018, 7, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.; Ur Rehman, S. Perceived Benefits and Perceived Risks Effect on Online Shopping Behavior with the Mediating Role of Consumer Purchase Intention in Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 26, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duroy, D.; Gorse, P.; Lejoyeux, M. Characteristics of online compulsive buying in Parisian students. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1827–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M.S. Diffusion of e-commerce: An analysis of the adoption of four e-commerce activities. Telemat. Inform. 2002, 19, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukar-Kinney, M.; Ridgway, N.M.; Monroe, K.B. The Relationship Between Consumers’ Tendencies to Buy Compulsively and Their Motivations to Shop and Buy on the Internet. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Sun, Y.C. Using instant messaging to enhance the interpersonal relationships of Taiwanese adolescents: Evidence from quantile regression analysis. Adolescence 2009, 44, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, L.; Osualdella, D.; Di Blasio, P. Quality of Interpersonal Relationships and Problematic Internet Use in Adolescence. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B.; Hasse, A.Q.; Witte, J.; Hamptom, K. Does the Internet Increase, Decrease, or Supplement Social Capital? Social Networks, Participation, and Community Commitment. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 45, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. Connection strategies: Social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becchetti, L.; Manfredonia, S.; Pisani, F. Social Capital and Loan Cost: The Role of Interpersonal Trust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-X.; Fang, X.-Y.; Yan, N.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Yuan, X.-J.; Lan, J.; Liu, C.-Y. Multi-family group therapy for adolescent Internet addiction: Exploring the underlying mechanisms. Addict. Behav. 2015, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Q.; Song, P.; Wang, Z. Parent marital conflict and Internet addiction among Chinese college students: The mediating role of father-child, mother-child, and peer attachment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Gwung, H.-L.; Li, C.-H. Can Internet Usage Positively or Negatively Affect Interpersonal Relationship? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Simone, M.; Geiser, C.; Lockhart, G. Development and Validation of the Multicontextual Interpersonal Relations Scale (MIRS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2020, 36, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, N.K.; Zhang, Y.B.; Kunkel, A.; Ledbetter, A.; Lin, M.-C. Relational quality and media use in interpersonal relationships. New Media Soc. 2007, 9, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.J. Online Communication and Adolescent Social Ties: Who benefits more from Internet use? J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.H.; Bai, Z.Q.; Wei, J.X.; Yang, M.L.; Fu, G.F. The Status Quo of College Students’ Online Shopping Addiction and Its Coping Strategies. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 11, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Attachment; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, W.A.; Martin, I.M.; Mason, M.J. In search of well-being: Factors influencing the movement toward and away from maladaptive consumption. J. Consum. Aff. 2020, 54, 1178–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnish, R.J.; Roche, M.J.; Bridges, K.R. Predicting compulsive buying from pathological personality traits, stressors, and purchasing behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 177, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong Tjin Tai, E. Data ownership and consumer protection. J. Eur. Consum. Mark. Law 2018, 7, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asswad, J.; Marx Gómez, J. Data Ownership: A Survey. Information 2021, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, J.; Ritch, E.L. The Evolution of Big Data in Marketing: Trust, Security and Data Ownership. In New Perspectives on Critical Marketing and Consumer Society; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fadler, M.; Legner, C. Data ownership revisited: Clarifying data accountabilities in times of big data and analytics. J. Bus. Anal. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish, H.V.; Gehrke, J.; Labrinidis, A.; Papakonstantinou, Y.; Patel, J.M.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Shahabi, C. Big data and its technical challenges. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beke, F.T.; Eggers, F.; Verhoef, P.C. Consumer Informational Privacy: Current Knowledge and Research Directions; Now: Norwell, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 11, pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendelson, D.; Mendelson, D. Legal protections for personal health information in the age of Big Data—A proposal for regulatory framework. Ethics Med. Public Health 2017, 3, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, H.K.; DeMuro, P.R. Developments in Privacy and Data Ownership in Mobile Health Technologies, 2016–2019. Yearb. Med. Inf. 2020, 29, 032–043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, P.; Sivakumaran, B.; Marshall, R. Impulse buying and variety seeking: A trait-correlates perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, H.J. Understanding the means and objects of addiction: Technology, the internet, and gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 1996, 12, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Dèttore, D.; Casale, S. Adolescent Internet Addiction: Testing the Association Between Self-Esteem, the Perception of Internet Attributes, and Preference for Online Social Interactions. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.S. The Effect of Stress on Smartphone Addiction in Nursing Students: The Mediating Effect of Interpersonal Relationship. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, A.; Park, S.; Kim, D.-J.; Choi, J.-S. The Relationship between Impulsivity and Internet Gaming Disorder in Young Adults: Mediating Effects of Interpersonal Relationships and Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stutzman, F.; Vitak, J.; Ellison, N.; Gray, R.; Lampe, C. Privacy in Interaction: Exploring Disclosure and Social Capital in Facebook. In Proceedings of the 6th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Dublin, Ireland, 4–7 June 2012; Volume 6, pp. 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online Social Networks: Why We Disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, K.T.; Choi, S.K.; Lee, B.G. SNS flow, SNS self-disclosure and post hoc interpersonal relations change: Focused on Korean Facebook user. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepte, S.; Masur, P.K.; Scharkow, M. Mutual friends’ social support and self-disclosure in face-to-face and instant messenger communication. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 158, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.D.; Bearman, P.S.; Blum, R.W.; Bauman, K.E.; Harris, K.M.; Jones, J.; Tabor, J.; Beuhring, T.; Sieving, R.E.; Shew, M.; et al. Protecting Adolescents from Harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997, 278, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Manolis, C.; Tanner, J.F. Interpersonal influence and adolescent materialism and compulsive buying. Soc. Influ. 2008, 3, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-P.; Wu, J.Y.-W.; You, J.; Chang, K.-M.; Hu, W.-H.; Xu, S. Association between online and offline social support and internet addiction in a representative sample of senior high school students in Taiwan: The mediating role of self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Wang, M.C.-H. Social Support and Social Interaction Ties on Internet Addiction: Integrating Online and Offline Contexts. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barkham, M.; Hardy, G.E.; Startup, M. The IIP-32: A short version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 35, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, X.-L.; Liaw, S.-Y. Psychometric evaluation of Online Shopping Addiction Scale (OSAS). J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The Analysis of Mechanisms and Their Contingencies: PROCESS versus Structural Equation Modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchiraju, S.; Sadachar, A.; Ridgway, J.L. The Compulsive Online Shopping Scale (COSS): Development and Validation Using Panel Data. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, N.M.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Monroe, K.B. An Expanded Conceptualization and a New Measure of Compulsive Buying. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dittmar, H. A New Look at “Compulsive Buying”: Self-Discrepancies and Materialistic Values as Predictors of Compulsive Buying Tendency. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 832–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A.S.; Biswas, A. A Study of Factors of Internet Addiction and Its Impact on Online Compulsive Buying Behaviour: Indian Millennial Perspective. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 1448–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mikołajczak-Degrauwe, K.; Brengman, M. The influence of advertising on compulsive buying—The role of persuasion knowledge. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homburg, C.; Baumgartner, H. Beurteilung von Kausalmodellen—Bestandsaufnahme und Anwendungsempfehlungen. Mark. Z. Forsch. Prax. 1995, 17, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R.; Hamidi, S. Online shopping as a substitute or complement to in-store shopping trips in Iran? Cities 2020, 103, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. The prevalence of compulsive buying: A meta-analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mangleburg, T.F.; Doney, P.M.; Bristol, T. Shopping with friends and teens’ susceptibility to peer influence. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuseir, M.T. The impact of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) on the online purchase intention of consumers in the Islamic countries—A case of (UAE). J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 10, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.S.; Che Hussin, A.R.; Busalim, A.H. Influence of e-WOM engagement on consumer purchase intention in social commerce. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Nayak, J.K. The Effects of Stress and Human Capital Perspective on Compulsive Buying: A Life Course Study in India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Compulsive Buying Among College Students: An Investigation of Its Antecedents, Consequences, and Implications for Public Policy. J. Consum. Aff. 1998, 32, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-H.; Chen, M.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Chung, T.-Y.; Lee, Y.-A. Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Azam, R.I. Social comparison, materialism, and compulsive buying based on stimulus-response-model: A comparative study among adolescents and young adults. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R.-N. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemou, K.; Karyda, M.; Kokolakis, S. Directions for Raising Privacy Awareness in SNS Platforms. In Proceedings of the 18th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics, Athens, Greece, 2–4 October 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).