Over the past few decades, the issue of climate change has become increasingly more critical for nearly all economic market sectors. In order to maintain the global average temperature well below 2 °C more than pre-industrial levels, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has set the target of net zero emissions by 2050 [

1,

2]. This means that the amount of GHG emitted into the atmosphere minus the quantity taken off of it equals zero [

1,

2]. In particular, GHG emissions are mainly caused by the combustion of fossil fuels, which occurs along the value chain of the energy sector. Therefore, energy companies are definitely among the most involved and affected by the urgency of reducing GHG emissions. This is where carbon management comes into play: it allows companies to rethink their business, goods, and services towards achieving a low-carbon economy [

3]. In fact, energy companies now face the task of substantially restructuring their value chains and leading the way in the technological transition to renewable sources of energy or electric vehicles for instance, and they have a limited timespan to achieve this goal [

4]. Therefore, carbon management is crucial in order to both meet the targets on emissions set by governments and to adopt the most cost-effective plan available.

Nonetheless, not all states have set net zero by 2050 as a target yet. Thailand, despite having undertaken a phase of rapid implementation of policies over the last decades, has only pledged to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to reduce its GHG emissions 20% by 2030, with no further indication regarding future developments [

5]. This leaves the companies significantly more room and time to re-organize themselves into low-carbon businesses compared with other countries which set more stringent targets. Analyzing Thailand’s energy sector can thus provide insights as to how companies behave in the absence of severe regulatory frameworks and specific guidelines on how to proceed. Moreover, among Thai firms in this branch, PTT represents a peculiar case due to three main reasons: firstly, it is significantly larger and more important than the others in terms of revenues, emissions, and number of employees and countries in which it operates [

6,

7]. Secondly, it is a state-owned company: the major shareholder is the Ministry of Finance with 51% [

8]. Thirdly, PTT’s GHG emissions have fluctuated around 155–160 MtCO

2e per year, while Thailand’s emissions were near to 300 MtCO

2e per year. Although not all of PTT’s emissions are calculated into Thailand’s total, it is clear that PTT’s carbon management decisions will greatly influence Thailand’s performance overall. It is thus interesting in this case to observe how the government paves the way for the transition to a low-carbon economy using its most powerful company and how it approaches its own policies on GHG emissions reductions. The current state of the literature has thus far analyzed carbon management practices from different perspectives: most notably, Doda et al., explored the role of harmonized reporting standards in corporate accounting [

9]; Tang et al. compared firms’ carbon management systems [

10]; Herold et al. focused on how carbon management practices reflect on different carbon disclosure strategies [

11]; and Shi et al. explored the effects of spontaneous combustion of coal [

12,

13]. Overall, the case studies considered mainly consisted of private companies. In light of this, studying the case of PTT can provide additional insights regarding the approach taken by state-owned companies in order to comply with substantially self-imposed regulations.

1.1. Overview of the Firm

PTT is a state-owned company that works in the energy sector. It is the most influential in Thailand in terms of annual revenues, which oscillated between USD 67 billion and USD 70 billion in the last five years [

7]. The only exception to this has been 2020 in which, due to the COVID-19 breakout, the total revenues amounted to USD 50 billion [

7]. PTT’s businesses are not limited to Thailand solely: it currently operates in eleven countries all around the world, in thirty-nine different projects [

7]. PTT’s employees number 4616 at the headquarter location in Thailand and 24,680 in subsidiaries spread across those eleven countries. Its businesses encompass several sub-fields in the energy sector: gas, oil, petrochemicals, infrastructures, coal, and renewable sources. In the gas chain, PTT has projects dedicated to exploration and production and gas separation plants [

7,

14]. As for infrastructure, PTT operates with gas transmission pipelines and coal transportation railways [

7,

14]. Regarding the oil chain, PTT extracts oil in situ which it then either trades or processes in its refineries [

7,

14]. Lastly, the refined oil is either sold B2B covering corporate customers, private and public organizations or agencies, or B2C mainly to gas stations and households [

7,

14]. The value chain of coal was incorporated as well, from mining and transportation to power plants processing and distribution [

7,

14]. Lastly, PTT has lately committed to investments in solar energy with the creation of PVs and distribution [

15].

1.2. Pledges

PTT has not pledged to reach carbon neutrality. The only target set by the company so far is to reduce its GHG emissions 20% by 2030 [

16]. The reason behind this is that the state of Thailand itself has made no other pledge except for this one. Indeed, it is not the duty of the company to implement action beyond what is established by the government. As PTT is a state-owned company, it is expectable that it will align its business with the legal framework in place. Although Thailand’s only pledge was to reduce emissions by 20% within 2030, the government set several internal targets in its climate-change-related policies. The regulatory framework for this field is extremely complex and it is constituted by more than 30 policies on a regional and national level, yet the overarching laws in place at the moment are [

17]: the National Strategy (2018–2037), the Climate Change Master plan, the Energy Efficiency Plan (EEP), and the Alternate Energy Development Plan (AEDP). AEDP is the one that provides the most guidelines concerning the transition to a low-carbon economy for the energy sector, thus for the PTT. In particular, it states that the share of renewable energy will have to increase to 30% by 2036 which requires the installation of new facilities to generate 19.6 GW [

18]. Concerning electricity generation, this will be achieved through a mix of renewable energy composed of biomass, biogas, wind, hydro, and solar [

18]. As for heat in both private and public buildings, 37% of the total demand will be covered by renewable sources [

18].

PTT has not yet included any of these targets in its pledge to reduce GHG emissions 20% by 2030. This may be due to the fact that PTT is still in the decision-making phase regarding where and how to allocate its budget for the GHG emissions reduction plan.

1.3. Emissions Estimates

PTT has published its organizational emissions estimates over the last few years. These were calculated by applying the due formulas depending on the type of coal, gas, or cause of emission as outlined in the national emissions account factor. The emission factors were instead retrieved from the WRI Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard [

19].

Figure 1 represents the totality of PTT’s Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. The term Scope 1 refers to direct emissions from a company’s own activities [

20]. Scope 2 instead consists of emissions derived from the generation of purchased energy [

20]. Lastly, Scope 3 is the emissions that occur along the whole value chain of the company [

20].

It must be noted that Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions have not witnessed significant changes over the past six years [

16]. This shows that PTT did not make efforts to abate emissions caused by its own activities or by the generation of purchased energy. As for Scope 3 emissions, similarly to Scope 1 and 2, it is not possible to observe relevant changes in the past few years, the only exception to this being 2020 [

16]. However, it is likely that the slight decrease in emissions witnessed in 2020 is due to the breakout of COVID-19 and its consequent diminished opportunity for businesses and projects.

Clarification is needed regarding Scope 3 emissions: on its report, PTT specified that “data on Scope 3 on the website is only on fuel combustion activities that PTT sells (use of sold products)” [

16]. Moreover, PTT has not published any data regarding other possible sources of Scope 3 emissions such as employees’ business travel, disposal of waste generated, or transportation of products and materials. Nevertheless, when dealing with energy companies, “use of sold products” causes an outstandingly large amount of GHG emissions compared with the other Scope 3 sources. For instance, it is possible to portray the emissions derived from employees’ business air travel by using the ICAO calculator. Although PTT has not disclosed data regarding how many business flights are taken by PTT employees per year, assuming one round trip per month towards every nation PTT operates in will give an idea of the order of magnitude of air travel related to Scope 3 emissions: in this case, it would amount to 56.4 tCO

2 per year which is irrelevant compared with PTT emissions derived from the use of sold products, meaning 124.49 MtCO

2e in 2017 as an example. Furthermore, other multinational energy companies such as Eni or Shell report that emissions caused by the use of sold products represent the vast majority of the total Scope 3 emissions [

21]. Therefore, in the peculiar case of energy companies, the use of sold products can be considered a valid and representative account of the total Scope 3 emissions. Still,

Figure 1 clearly shows that nearly no efforts have been made by PTT to reduce GHG emissions over the last five years, which is representative of the fact that Thailand had not made a pledge regarding the time frame 2015–2020 in its NDCs.

The lack of improvements in emissions reductions over the last years by PTT is, however, in line with most of the other multinational energy companies’ performance [

22]. Overall, most companies’ reduction plans have not yet been entered into force, thus this sector has not shown significant emissions reductions, as shown in

Figure 2 below [

22]:

Although PTT’s trend of GHG emissions is similar to that of the global energy sector, PTT still lags behind in the transition to low-carbon businesses compared with its competitors because its GHG emissions reduction plan lacks specific and concrete targets, as will be discussed in the following section.

1.4. Emissions Reductions

While PTT has not made significant efforts to reduce its GHG emissions so far, now it faces the task of meeting the target set by Thailand of reducing GHG emissions 20% by 2030. To comply with the target, PTT set out its Climate Change Management plan [

16]. The plan provides guidelines for business and investment directions that PTT will undertake to favor its transition to a low-carbon economic model. However, compared with other companies’ reduction plans, such as Eni or Shell, PTT’s strategy does not include specific targets, investment budgets, costs, details on the projects, nor estimates regarding future emissions reductions. Similarly, Thailand’s targets outlined in AEDP were not included nor mentioned in the report. As aforementioned, PTT is still in the decision-making phase regarding how to concretely take actions to achieve the 20% reduction. Bearing this in mind, this section will first describe the guidelines provided by PTT in its Climate Change Management plan, and then it will analyze the most significant methods to try to provide an estimate of their costs and GHG reduction potential. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that PTT’s Scope 1 + 2 + 3 emissions in the last years were stably close to 157.83 MtCO

2e [

16]. Thus, having to reduce it by 20% means a total reduction needed of 31.57 MtCO

2e by 2030.

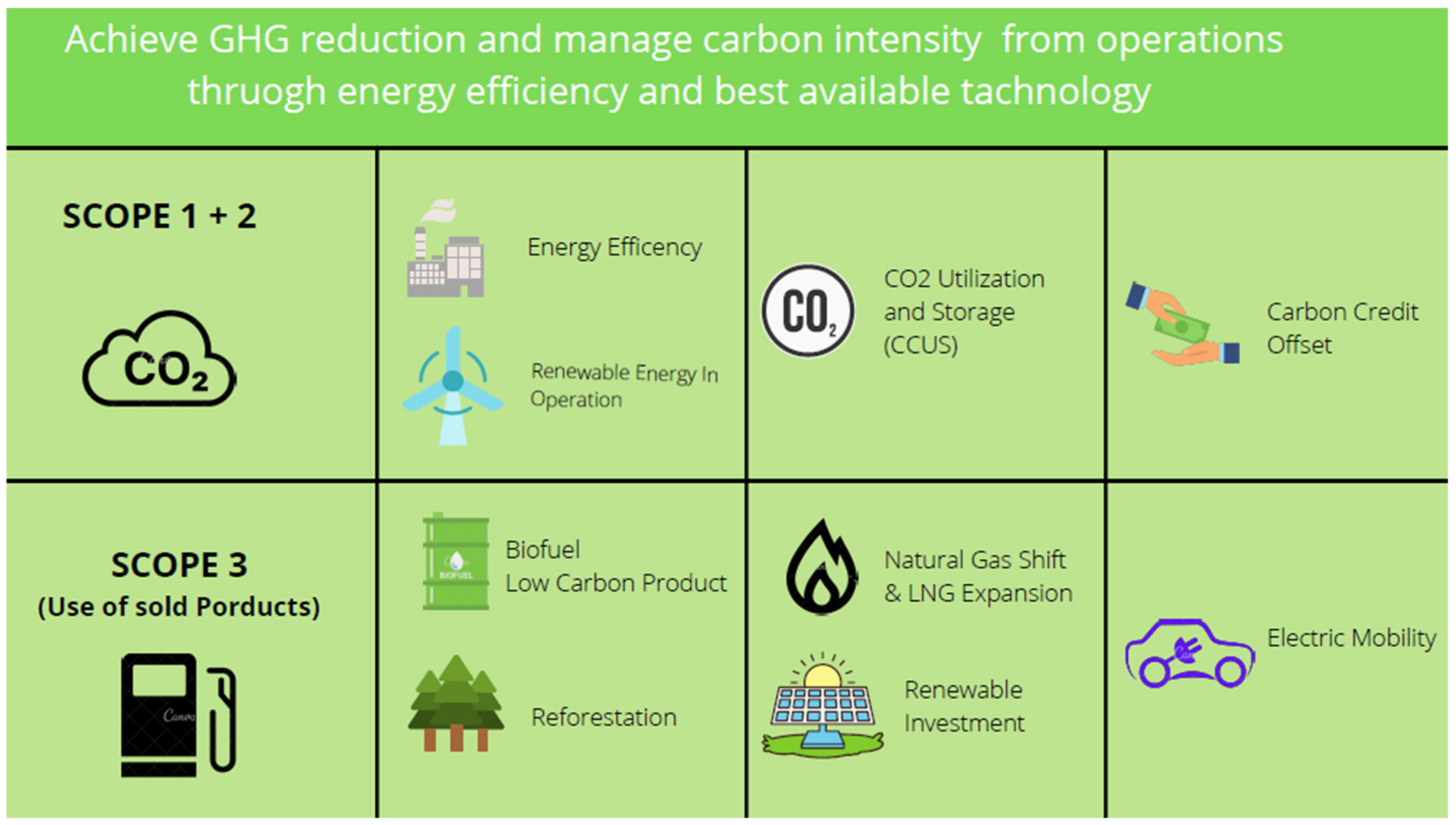

To achieve the goal of reducing emissions, PTT outlined three different approaches to operation: controlling GHG emissions from business operations, increasing the quantity of clean and low-carbon products, and operating new clean and low-carbon businesses [

16]. Specifically, concerning Scope 1 and 2 emissions, PTT aims to: optimize renewable energy sources already in place, improve overall energy efficiency, and make use of Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS) technologies and carbon credit offsets. Instead, as far as Scope 3 emissions are concerned, PTT seeks to boost the production of biofuels, increase investments for constructing renewable sources of energy facilities, allocate budgets for research and construction of electric vehicles, shift towards natural gas over coal and oil as a source of energy, and buy carbon offsets in the form of REDD+ forest conservation projects [

16]. Additionally, PTT inserted carbon pricing as a tool for enhancing investments in low-carbon businesses and projects. The shadow price adopted during the decision-making phase and investments considerations will be USD 20 per tCO

2e [

16].

Figure 3 below summarizes PTT’s guidelines for emissions reductions following the Scope 1, 2, and 3 categorizations [

16].

As mentioned above, PTT has not officially published details regarding how to concretely implement these guidelines. There is a lack of specification regarding the amount of MtCO

2e emissions reduced and the costs, nor are details on which projects will be undertaken in order to achieve the targets provided. The information published on the website is incomplete. Therefore, in order to evaluate the degree of impact that the methods available to PTT are likely to have in terms of GHG emissions reduction and the relative costs, it was necessary to integrate PTT’s officially published strategy with public announcements retrieved from newspapers or journals, and use other companies’ significantly more detailed reports to provide accurate estimates. Eni, an energy company operating in Europe will be used most to this extent because it is similar to PTT in terms of revenue, number of employees, and types of businesses [

16,

21]. The three methods compared will be: carbon offsets, investment in renewable sources of energy, and CCUS.

Regarding carbon offsets, PTT’s focus has always been on REDD+ forestation conservation projects. In particular, it has promoted the Network for Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation in Thailand, which works with the Green Globe Network aiming at reforestation of areas previously encroached or damaged [

24,

25]. Similarly, it undertook various reforestation projects by creating the “PTT Reforestation and Ecosystem Institute” [

24,

25]. PTT’s guidelines for emissions reductions are to continue along this trend of investing in reforestation and conservation of biodiversity projects [

16]. The budget allocated to this goal is not specified, however, most REDD+ projects tend to cost USD 5–10 per tCO

2e offset [

26]. The total cost naturally depends on the number of emissions that have to be offset, which was not disclosed either. Nevertheless, as an example to capture the order of magnitude of GHG reductions and cost, it is possible to consider that Eni plans to be offsetting 6 MtCO

2e by 2024 and 10 MtCO

2e by 2030 [

21]. Thus, it will bear the cost of USD 50–100 million per year by 2030. A similar reasoning could be applied to PTT. Interestingly, if PTT decides to disregard the transition to renewable sources and low-carbon economic models, and focuses on offsetting all of the 31.57 MtCO

2e emissions to reach the 2030 target through REDD+ projects solely, this would be relatively cheap at a cost between USD 157.8 million and USD 315.7 million per year. Nevertheless, this is profitable only in the short term, because in the long run energy companies will be imposed with further targets on emissions and the energy market will most likely convert to renewable sources and low-carbon businesses. To this extent, carbon offsets represent a cost that does not create new business opportunities, which might be suitable for other companies, yet not for those working in the energy sector.

The second method of emissions reduction is constituted by investments in renewable sources of energy. According to Reuters [

27] and Bloomberg [

28], Mr. Auttapol Rerkpiboon, president and CEO of PTT, claimed to increase the share of renewable sources of energy from 8 GW to 12 GW. Assuming that CO

2e emissions derived from renewable energies are irrelevant compared with those caused by fossils fuels, it is possible to calculate the emissions reductions by looking at what would have been emitted if those 4 GW of difference were emitted from fossils fuels. Emissions derived from purchased electricity can be calculated through the formula:

The emission factor in question can be retrieved from WRI’s GHG protocol [

19]. Given all this, the investment in renewable energy can ensure a reduction of 21.7 MtCO

2e per year. Moreover, Eni as well has set the target of investing in renewable energies to generate 4 GW [

21]. Eni allocated a budget of USD 2.85 billion to this extent, which should be representative of what PTT would similarly need to spend.

The last method to discuss is the implementation of CCUS technologies. However, these are still in the development phase and offer limited room for reduction. Eni foresees a potential of 3 MtCO

2e per year. PTT plans to start adopting CCUS by 2025 when it will allow more room for reduction and will arguably be cheaper than current costs [

29]. For the time being, the cost of CCUS technologies is estimated to be between USD 20 USD and USD 25 per tCO

2e, thus significantly more expensive than carbon offsets [

29]. Nevertheless, depending on the budget available, carbon offsets have significantly more potential for emissions reduction. Compared with these two methods, investing in renewable sources of energy is outstandingly more expensive initially, yet it of course offers a return on investment once the electricity is sold, and it offers the possibility for undertaking new projects and businesses in the sector of renewable energies.

In conclusion, although PTT has not yet made significant concrete efforts to reduce its emissions, it is clear that the options available allow for meeting the target of 20% reductions by 2030 for a total of 31.57 MtCO2e, at a relatively low cost compared with PTT’s annual revenues which oscillate between USD 67 billion and USD 70 billion.