Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

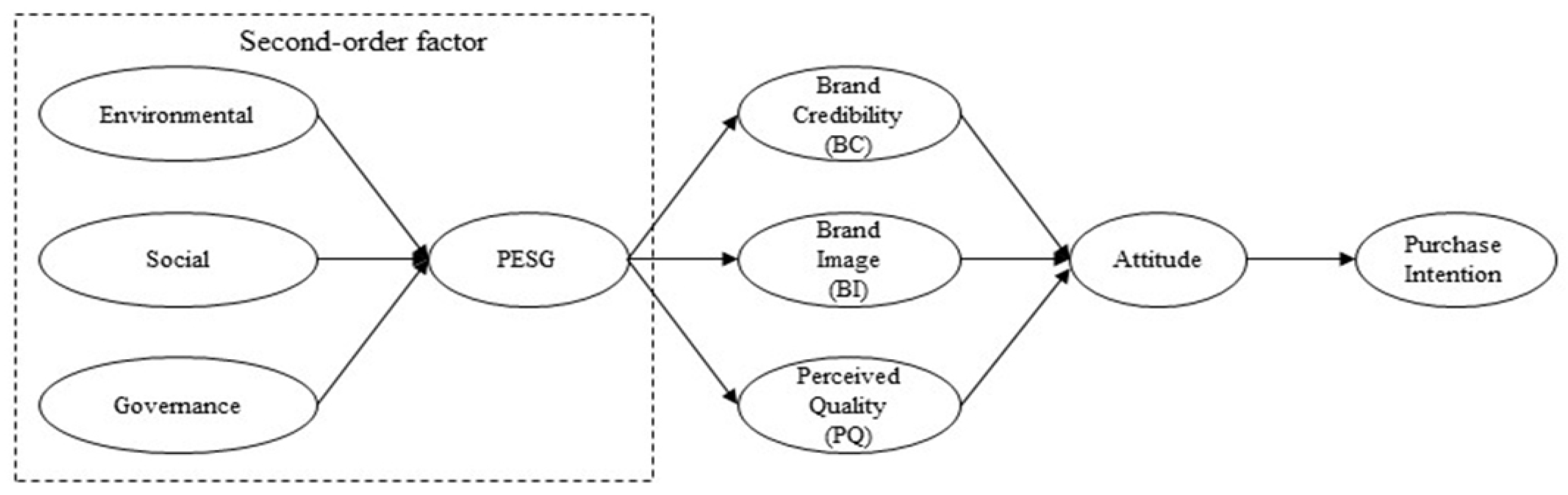

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. ESG

2.2. Perceived ESG and Its Effects

2.2.1. Perceived ESG on Brand Credibility

2.2.2. Perceived ESG on Brand Image

2.2.3. Perceived ESG on Perceived Quality

2.3. Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality

2.4. Attitude on Purchase Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Design and Sample

3.2. Measures

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Main Effects

4.2.2. Mediating Effects

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Program Finance Initiative. A Legal Framework for the Integration of Environmental, Social and Governance Issues into Institutional Investment; United Nations Environment Program Finance Initiative: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- BlackRock. Sustainability as BlackRock’s New Standard for Investing. 2020. Available online: https://www.blackrock.com/us/individual/blackrock-client-letter (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregate evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B.A.; Hamdan, A. ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 1409–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Harrison, D.E.; Ferrell, L.; Hair, J.F. Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Byun, R. Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyundai. ESG Is New Paradigm of Corporate Management. Available online: https://en.hdec.kr/en/newsroom/news_view.aspx?NewsSeq=178&NewsType=FUTURE&NewsListType=news_clist#.YKR0eLdLjIV (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Miralles-Quiros, M.M.; Miralles-Quiros, J.L.; Valente Goncalves, L.M. The value relevance of environmental, social, and governance performance: The Brazilian case. Sustainability 2018, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Social Investment Forum (USSIF). Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends. 2014. Available online: http://www.ussif.org/Files/Publications/SIF_Trends_14.F.ES.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2016).

- Garcia, A.S.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z. Business sustainability research: A theoretical and integrated perspective. J. Account. Lit. 2016, 36, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Jain, A.; Rezaee, Z. Value-relevance of corporate social performance: Evidence from short selling. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2016, 28, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.G. Environmental social governance management: A theoretical perspective for the role of disclosure in the supply chain. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2015, 18, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, K.K. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand image. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2014, 25, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.M.; Lee, S.; Jeong, M. Perceived corporate social responsibility and customers’ behaviors in the ridesharing service industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.T.; Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Retailer corporate social responsibility and consumer citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling green! Firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, M.B.; Talay, M.B. Cultural variations in the use of marketing signals: A multilevel analysis of the motion picture industry. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J.; Valenzuela, A. Brands as signals: A cross-country validations study. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Zayyad, H.M.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Abuhashesh, M.; Maqableh, M.; Masadeh, R. Corporate social responsibility and patronage intentions: The mediating effect of brand credibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 510–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unrich, S.; Koenigstorfer, J.; Groeppel-Klein, A. Leveraging sponsorship with corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 67, 2023–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Gilal, F.G.; Channa, N.A.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, N. Corporate social responsibility and brand passion among consumers: Theory and evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukemura, P.K. Why ESG Investing Seems to Be an Attractive Approach to Investment in Brazil. Bachelor Thesis, Polytechnic University of Milan, Sao Paolo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gurlek, M.; Duzgun, M.; Uygur, S.M. How does corporate social responsibility create customer loyalty? The role of corporate image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kim, E.Y. Green marketing’ functions in building corporate image in the retail setting. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmones, M.D.; Crespo, A.H.; Bosque, I.R.D. Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; James, J. Service quality dimensions: An examination of Gronroos’s service quality model. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2004, 14, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Saha, R.; Goswami, S.; Dahiya, R. Consumer’s response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Wang, W.H. Impact of CSR perception on brand image, brand attitude and buying willingness: A study of a global café. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.M. Market Signaling; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liao, Y.K.; Wu, W.Y.; Le, H.B. The role of corporate social responsibility perceptions in brand equity, brand credibility, brand reputation, and purchase intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhatacharaya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Bodwell, C.; Graves, S.B. Responsibility: The new business imperative. Acad. Bus. Exec. 2002, 16, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Brands and branding: Research findings and and future priorities. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.; Galan, J.I. Effects of corporate social responsibility on brand value. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Ji, H.L.; Lan, F. A study on the perceived CSR and customer loyalty based on the dairy market in China. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Tokyo, Japan, 28–30 June 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Shi, G.; Chu, G.; Brock, J.L. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, P.; Nishiyama, N. Enhancing customer-based brand equity through CSR in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacap, J.P.; Cham, T.H.; Lim, X.J. The influence of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty and the mediating effects of brand satisfaction and perceived quality. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2021, 15, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Swaen, V.; Chumpitaz, R.C. Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2008, 23, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Biar, S. Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J.; Louviere, J. The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2002, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Aleman, F.L. Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause-brand alliance when consumer evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, S.J.; Goldsmith, R.E. The development of a scale to measure perceived corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Fatima, T.; Ahmad, S. Signaling effect of brand credibility between fairness (price, product) and attitude of women buyers. Abasyn J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 13, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.V.; Herrera, A.A.; Perez, R.C. Do consumers really care about aspects of corporate social responsibility when developing attitudes toward a brand? J. Glob. Mark. 2021, 1–15. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08911762.2021.1958277 (accessed on 1 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, T.R. Using promotional messages to manage the effects of brand and self-image on brand evaluations. J. Consum. Mark. 1996, 13, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I. The interference effect of perceived CSR on relationship model of brand image. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, M.; Woo, H.; Kim, S. Sincerity or ploy? An investigation of corporate social responsibility campaigns. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Chang, W.C.; Lee, H.C. An investigation of the effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and customer loyalty—Evidence from the Taiwan non-life insurance industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Rashid, B. A conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomvilailuk, R.; Butcher, K. Enhancing brand preference through corporate social responsibility initiatives in the Thai banking sector. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2010, 22, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.K. The impact of corporate reputation on brand attitude and purchase intention. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpitch, S.; Minakan, N.; Powpaka, S.; Laohavichien, T. Effect of corporate social responsibility motives on purchase intention model: An extension. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 37, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Lee, K.S.; Baek, H. Impact of corporate social responsibilities on customer responses and brand choices. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Yoon, S.J. The effect of customer citizenship in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on purchase intention: The important role of the CSR image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H.; Yu, J.E.; Choi, M.G.; Shin, J.I. The effects of CSR on customer satisfaction and loyalty: The moderating role of corporate image. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z.; Perez, A. The sharing economy: The influence of perceived corporate social responsibility on brand commitment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KCGS. 2009. Available online: http://www.cgs.or.kr/business/esg_tab04.jsp (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Akbari, M.; Mehrali, M.; SeyyedAmiri, N.; Rezaei, N.; Pourjam, A. Corporate social responsibility, customer loyalty and brand positioning. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Caruana, A.; Snehota, I. The role of corporate social responsibility, perceived quality and corporate reputation on purchase intention: Implications for brand management. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 20, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, F.S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices and stakeholder expectations: The Nigerian perspectives. Res. Bus. Manag. 2014, 1, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Afzali, H.; Kim, S.S. Consumers’ responses to corporate social responsibility: The mediating role of CSR authenticity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KCCI. A Survey on Public Awareness about ESG Management and the Role of Firms. 2021. Available online: http://www.korcham.net/nCham/Service/Economy/appl/KcciReportDetail.asp?SEQ_NO_C010=20120933852&CHAM_CD=B001 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y. Effects of multi-brand company’s CSR activities on purchase intention through a mediating role of corporate image and brand image. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Lin, H.F. The correlation of CSR and consumer behavior: A study of convenience store. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Structural equation models with unobserved variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, L.M. Assessing a second-order quality of school life construct suing partial least squares structural equation modelling approach. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2020, 43, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Z. How CSR influences customer behavioral loyalty in the Chinese hotel industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Gopinath, C. Corporate social responsibility and customer behavior: A developing country perspective. Lahore J. Bus. 2015, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices on brand equity formation: Do green practices really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, I.; Khetriwal, D.S. Exploring the relationship between environmental orientation and brand value: Is there fire or only smoke? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Shin, D. Consumers’ responses to CSR activities: The linkage between increased awareness and purchase intention. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Fatma, M. Connecting the dots between CSR and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand experience and brand trust. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2019, 17, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 223 | 48.7 |

| Female | 235 | 51.3 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 91 | 19.9 |

| 30–39 | 105 | 22.9 | |

| 40–49 | 125 | 27.3 | |

| 50–59 | 137 | 29.9 | |

| Monthly Household Income | Less than 2000 | 103 | 22.5 |

| 2000–4000 | 198 | 43.2 | |

| 4000–7000 | 115 | 25.1 | |

| More than 7000 | 42 | 9.2 | |

| Education | High school or below | 69 | 15.1 |

| Junior college | 65 | 14.2 | |

| Bachelor | 269 | 58.7 | |

| Postgraduate and above | 55 | 12.0 | |

| Occupation | Student | 36 | 7.9 |

| Housewife | 52 | 11.4 | |

| Employee | 226 | 49.3 | |

| Governmental officer | 27 | 5.9 | |

| Businessman | 38 | 8.3 | |

| Professional | 47 | 10.3 | |

| Others | 32 | 7.0 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENV | ENV1 | 0.870 | 0.952 | 0.806 | 0.961 |

| ENV2 | 0.896 | ||||

| ENV3 | 0.892 | ||||

| ENV4 | 0.887 | ||||

| ENV5 | 0.907 | ||||

| ENV6 | 0.931 | ||||

| SOC | SOC1 | 0.819 | 0.934 | 0.716 | 0.946 |

| SOC2 | 0.803 | ||||

| SOC3 | 0.873 | ||||

| SOC4 | 0.851 | ||||

| SOC5 | 0.864 | ||||

| SOC6 | 0.845 | ||||

| SOC7 | 0.864 | ||||

| GOV | GOV1 | 0.815 | 0.938 | 0.765 | 0.951 |

| GOV2 | 0.880 | ||||

| GOV3 | 0.862 | ||||

| GOV4 | 0.905 | ||||

| GOV5 | 0.896 | ||||

| GOV6 | 0.885 | ||||

| BC | BC1 | 0.906 | 0.911 | 0.849 | 0.944 |

| BC2 | 0.928 | ||||

| BC3 | 0.930 | ||||

| BI | BI1 | 0.824 | 0.829 | 0.743 | 0.896 |

| BI2 | 0.878 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.882 | ||||

| PQ | PQ1 | 0.940 | 0.933 | 0.881 | 0.957 |

| PQ2 | 0.939 | ||||

| PQ3 | 0.937 | ||||

| AT | AT1 | 0.928 | 0.926 | 0.871 | 0.923 |

| AT2 | 0.944 | ||||

| AT3 | 0.927 | ||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.904 | 0.885 | 0.871 | 0.953 |

| PI2 | 0.879 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.921 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AT | 0.933 | |||||||

| 2. BC | 0.763 | 0.922 | ||||||

| 3. BI | 0.773 | 0.752 | 0.862 | |||||

| 4. ENV | 0.486 | 0.502 | 0.462 | 0.898 | ||||

| 5. GOV | 0.708 | 0.620 | 0.599 | 0.673 | 0.875 | |||

| 6. PI | 0.798 | 0.698 | 0.737 | 0.403 | 0.616 | 0.897 | ||

| 7. PQ | 0.789 | 0.755 | 0.740 | 0.463 | 0.671 | 0.731 | 0.939 | |

| 8. SOC | 0.730 | 0.688 | 0.664 | 0.735 | 0.809 | 0.809 | 0.658 | 0.846 |

| 2nd Order Construct | 1st Order Construct | Weight/Loading | VIF | t-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PESG | ENV-ESG | −0.118 (weight) 0.692 (loading) | 2.262 | 1.552 |

| SOC-ESG | 0.717 (weight) | 3.572 | 7.863 | |

| GOV-ESG | 0.419 (weight) | 3.009 | 5.018 |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PESG → BC | 0.695 | 24.082 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1a | ENV → BC | −0.040 | 0.717 | 0.474 | Not supported |

| H1b | SOC → BC | 0.562 | 7.812 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1c | GOV → BC | 0.193 | 2.896 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | PESG → BI | 0.706 | 24.667 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a | ENV → BI | −0.091 | 1.354 | 0.176 | Not supported |

| H2b | SOC → BI | 0.570 | 7.277 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2c | GOV → BI | 0.200 | 2.796 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | PESG → PQ | 0.701 | 23.630 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3a | ENV → PQ | −0.118 | 2.128 | 0.034 | Not supported |

| H3b | SOC → PQ | 0.399 | 5.538 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3c | GOV → PQ | 0.428 | 5.927 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | BC → AT | 0.225 | 4.651 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | BI → AT | 0.383 | 7.637 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H8 | PQ → AT | 0.328 | 7.183 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H10 | AT → PI | 0.804 | 44.791 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Effects | Path | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAF | Sobel Test | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Stat. | S. E | Stat. | S. E | ||||||

| Direct without mediator | PESG → AT | 0.624 | 21.431 | 0.029 | Not applicable | Supported | ||||

| Indirect with mediator | H5: PESG → BC → AT | |||||||||

| PESG → AT | 0.268 | 5.992 | 0.045 | 0.347 | 0.615 | 0.564 | 10.154 | 0.034 | Partial mediation | |

| PESG → BC | 0.673 | 21.829 | 0.031 | |||||||

| BC → AT | 0.517 | 11.809 | 0.045 | |||||||

| H7: PESG → BI → AT | ||||||||||

| PESG → AT | 0.245 | 5.971 | 0.041 | 0.372 | 0.617 | 0.603 | 11.865 | 0.031 | Partial mediation | |

| PESG → BI | 0.643 | 18.937 | 0.034 | |||||||

| BI → AT | 0.579 | 15.422 | 0.038 | |||||||

| H9: PESG → PQ → AT | ||||||||||

| PESG → AT | 0.232 | 5.773 | 0.040 | 0.386 | 0.618 | 0.624 | 11.437 | 0.033 | Partial mediation | |

| PESG → PQ | 0.672 | 19.903 | 0.034 | |||||||

| PQ → AT | 0.575 | 13.952 | 0.041 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koh, H.-K.; Burnasheva, R.; Suh, Y.G. Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084515

Koh H-K, Burnasheva R, Suh YG. Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084515

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoh, Hee-Kyung, Regina Burnasheva, and Yong Gu Suh. 2022. "Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084515

APA StyleKoh, H.-K., Burnasheva, R., & Suh, Y. G. (2022). Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality. Sustainability, 14(8), 4515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084515