Abstract

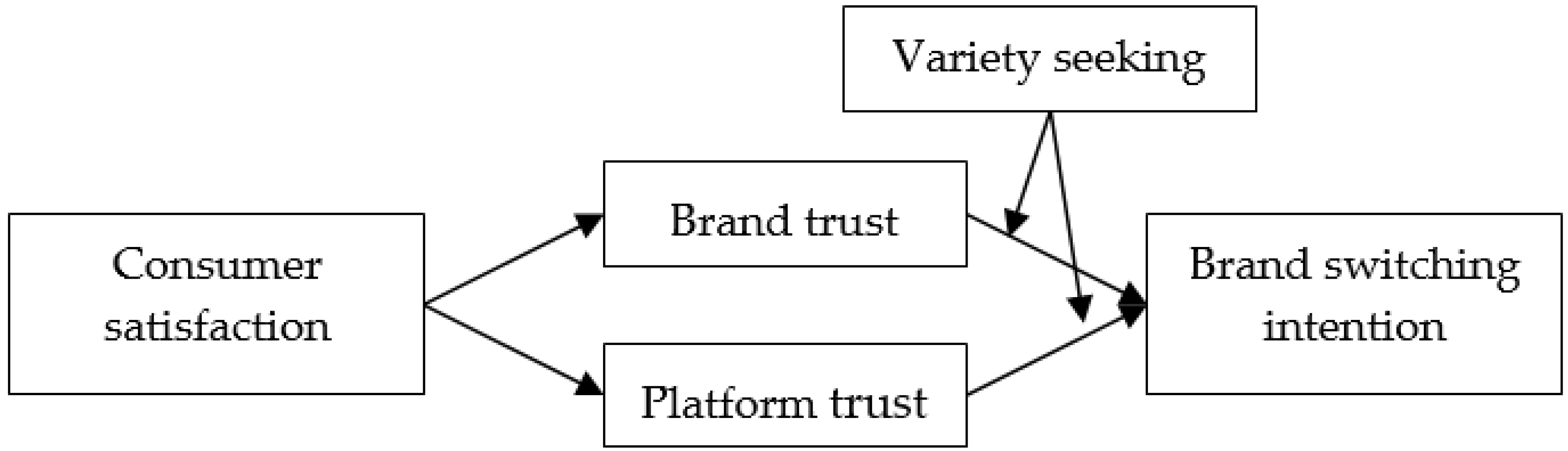

Previous studies have found that consumer satisfaction is negatively associated with brand switching intention in the common purchasing context; is this still true in the context of sharing apparel? This study aims to investigate the effect of consumer satisfaction on the brand switching intention of sharing apparel and to reveal the mechanism by exploring the mediating effects of brand trust and platform trust, integrating the moderating effect of variety seeking. Data were acquired from 346 consumers of sharing apparel through an online questionnaire survey. Hypotheses were tested in a moderated mediation model, with the bootstrapping method using the PROCESS program in SPSS. The empirical results demonstrated that the overall impact of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention was not significant, while the mediating effect of brand trust was significantly negative, and the mediating effect of platform trust was significantly positive. The moderating effect of variety seeking on the relationship between brand trust and brand switching intention was not significant, while the positive effect of platform trust on brand switching intention was stronger at higher levels of variety seeking. In addition, the mediating effect of platform trust on the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention was also stronger at higher levels of variety seeking. Therefore, there are dual effects of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention of sharing apparel through the different mediating effects of brand trust and platform trust. Based on these findings, we recommend that sharing apparel platforms could enlarge their return by fostering emerging brands or private brands, while premium brands should be cautious about fostering potential competitors when cooperating with sharing platforms.

1. Introduction

The fast fashion business has resulted in enormous amounts of textile waste and severe environmental pollution. As many clothes are usually used only a few times and disposed of nowadays, sustainable fashion has become an urgent issue, and sharing apparel may be a possible solution [1,2]. Sharing apparel is an emerging form of consumption where consumers rent apparels from platforms instead of purchasing them [2]. Even though it is viewed as a kind of sharing economy, it is not typical collaborative consumption shared among consumers [3]. In addition to providing various stylish clothes for consumers at lower cost, it also reduces the waste of clothes and protects the environment [2,3]. However, the business model of sharing apparel has long been questioned [4,5]. Despite the rapid growth of collaborative consumption, adaptation of sharing apparel is quite slow, let alone that more and more platforms have gone bankrupt or encountered severe operational difficulties since 2021.

As an emerging phenomenon, the academic research on sharing apparel is still quite limited. There have been several pioneer studies exploring the concept of collaborative consumption, adoption intention, and the business model of sharing apparel [4,5,6]. However, as consumers are renting instead of purchasing and interact with sharing apparel platforms instead of brands, their consumption psychology and behavior may be quite different from the traditional theories. For example, previous studies found that consumer satisfaction lessens brand switching intention [7,8,9]. However, consumption of sharing apparel not only involves the use of apparel provided by brands but also involves the experience of services provided by the platform. The taste, genuineness, newness, cleanness, and timely delivery of shared apparel may have a great influence on consumer satisfaction [1,2,6]. In turn, consumer satisfaction may not only promote trust in the brand, but also promote trust in the platform. Interestingly, the effects of brand trust and platform trust on brand switching intention may be opposite. Many previous studies have demonstrated that brand trust promotes brand loyalty and lessens brand switching intention in the common purchasing context [10,11,12]. It may also be true in the context of sharing apparel because trust in the brand reduces the risk in using apparel of the brand, regardless of purchasing or renting. In contrast, consumers who choose sharing apparel are usually trying to experience various types of apparel at a reasonable cost and avoid producing too much waste [1,3,6]. Trust in the platform indicates that trying new brands also has little risk because the platform provides a guarantee for the quality and services of other brands as well as the current brand [13,14]. Does platform trust increase brand switching intention? If consumer satisfaction promotes both brand trust and platform trust, while brand trust lessens brand switching intention and platform trust promotes it, what is the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention?

It is also noteworthy that the effects of brand trust and platform trust on brand switching intention may vary from person to person. Some consumers are more eager to experience different products, services, and brands and to seek variety in their consumption [15,16,17]. They tend to be less loyal to certain brands even if they find the brand satisfactory and trustworthy [15,18]. In the common purchasing context, consumer’s variety seeking weakens the effect of consumer satisfaction, perceived value, and brand trust on brand switching intention [19,20]. Will this also be true in the context of sharing apparel? In comparison, will variety seeking strengthen the effect of platform trust on brand switching intention? To address these issues, this study investigates the effect of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention and explores the mediating effects of brand trust and platform trust, integrating the moderating effect of variety seeking.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Consumer Satisfaction and Brand Trust

Consumer satisfaction is one of the key objectives of brand management and has attracted academic attention for decades. However, there is constant debate over the definition of consumer satisfaction because innumerable contextual factors affect how satisfaction is viewed [21]. This is especially true in that consumption of shared apparel is essentially different from common purchasing experiences. Even though any generic definition will be subject to chameleon effects, all context-specific definitions should contain three essential components of consumer satisfaction: summary affective response, satisfaction focus around consumption, and time of determination [21]. Following this framework, consumer satisfaction is defined as a summary affective response to the evaluation of the apparel and services provided by the sharing apparel platform after consumption. Consumption is always out of certain needs, and consumers want the products or services to be worth the money spent [22]. Specifically, they will judge the consumption based on the quality, emotion, price, and social values. Consumers will be satisfied when they find the products or services meet their expectation or become unsatisfied otherwise [23]. Even though consumers of sharing apparel do not purchase and own the apparel, the design, quality, and brand values of the apparel are also important for their consumption experience [2,5,6].

Brand trust is the willingness of the consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function [10]. Brand trust is developed from the interaction between consumers and the brand and becomes an affectional bond between them over time. It is found to be beneficial for maintaining frequent consumers, lowering marketing costs, and creating superior profits, which are all crucial to the success of brands [24,25,26]. Previous studies have demonstrated that consumer satisfaction promotes brand trust in the common purchasing context [27,28]. It may also be true in the context of sharing apparel. Even though the apparel is provided by the platform and consumers do not interact with the brand directly, the apparel was originally produced by the brand and has all the characteristics of the brand. When consumers are satisfied, it must be partially because of the apparel itself. In another words, if the apparel falls short of consumers’ expectation, consumers will never be satisfied no matter how good the platform’s services are. Therefore, we argue that consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with the brand trust of sharing apparel and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1.

Consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with brand trust.

2.2. Consumer Satisfaction and Platform Trust

There are still very few studies on platform trust, especially in the context of sharing apparel. The limited studies on platform trust had been conducted on the C2C e-commerce platform [29,30], P2P lending platform [31], social media platforms [32,33], and P2P e-commerce platform [34,35]. However, the essence of platform trust may be quite different for different kinds of platforms [36]. Sharing apparel platforms provide apparel owned by themselves, while most other platforms act only as an intermediary agent that connects the consumers and sellers. In other words, sharing apparel is not a typical kind of sharing economy that creates value by reducing the transactional cost but more as an ordinary service enterprise. However, sharing apparel platforms have an advantage in guaranteeing the products and services consumers receive, while other platforms can only supervise the sellers not to violate their rules. In this sense, trust in sharing apparel platforms is more direct and effective.

Different from focusing on the transactional obligations in a previous study [35], platform trust is defined as a user’s subjective perception that the platform will fulfill their obligations as the user understands them. Despite the quality, design, and brand values of the apparels, consumers of sharing apparel are also concerned about the newness, cleanness, and timely delivery of apparels that are provided by the platform [4,6]. Even if the apparels are of high quality and premium brands, consumers will also be unsatisfied if the apparels they receive are out of fashion, threadbare, dirty, or delivered slowly. Then, the unsatisfied consumers will no longer believe that the platform is going to fulfill their expectations [2,35]. It is also important for the platforms to provide genuine apparels, especially when they are of luxury brands [1]. When consumers are satisfied by their previous experience, they tend to believe that the risk of receiving counterfeit apparels in the future is low and will trust the platform [5]. Different platforms have different business models, such as pay-per-use or pay-per-month, share only or optional for purchasing with a discount. When consumers are satisfied, they are also satisfied with the platform’s business model. They tend to believe that the business model fits their demands and the platform will keep providing such good services. Therefore, we argue that consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with platform trust of sharing apparel and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2.

Consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with platform trust.

2.3. Brand Trust and Brand Switching Intention

Brand switching intention is the possibility of transferring a consumer’s existing transactions with a brand to a competitor [37]. Consumers usually keep purchasing the same brand because they get used to or feel attached to the brand or because there is a high switching cost [38,39,40]. On the other hand, they also switch to other brands out of boredom, dissatisfaction, or disidentification of the current brand, or the product advantage, lower price, preferential policies, or conveniences of other brands [8,37]. When consumers trust the current brand, they have faith in the brand’s capabilities in terms of design, quality, and brand values, and continue renting its apparels will satisfy their demands [41,42]. Brand trust also indicates that the consumers believe in the brand’s integrity that it will not copy other brands, violate the law, or pollute the environment, and continue renting its apparels will have little risk of scandals [43,44]. In addition, brand trust is also an affective bond between consumers and the brand, and consumers rely on and love to use the current brand [8,38]. Therefore, we argue that brand trust will be negatively associated with brand switching intention and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3a.

Brand trust will be negatively associated with brand switching intention.

Considering that consumer satisfaction is positively associated with brand trust and brand trust is negatively associated with brand switching intention, we also argue that consumer satisfaction will be negatively associated with brand switching intention through the mediating effect of brand trust and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3b.

Through the mediating effect of brand trust, consumer satisfaction will be negatively associated with brand switching intention.

2.4. Platform Trust and Brand Switching Intention

Interestingly, not only those who are unsatisfied will switch brands but also those who are satisfied, especially for hedonic products [18,45]. This may be even more true in the context of sharing apparel. Different from the common purchasing context, trying various apparels is one of the main reasons why consumers choose sharing apparels instead of purchasing them [1,6]. They are usually young consumers who wish to dress in various quality brands but cannot afford the costs. Therefore, they may rent other brands merely because they wish to try something new. However, there are also risks in such explorations. If the platform used some premium brands to attract consumers but offer them many unqualified brands or even some counterfeit apparels, brand switching is also a great risk. When they trust the platform, they have faith that the platform will continue providing apparels of good taste, high quality, and reassuring conditions as before [30,34]. As all the brands are selected and endorsed by the platform, consumers tend to believe that other brands are as good as the brand they have tried, even if they have little knowledge about them. In addition, they also believe that even if they encounter some unpleasant situations, the platform will take the responsibility and cover their loss [31,32]. Trust in the platform reduces the risk in trying new brands and provides space for consumers to explore. Therefore, we propose that platform trust will be positively associated with brand switching intention and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4a.

Platform trust will be positively associated with brand switching intention.

Considering that consumer satisfaction is positively associated with platform trust and platform trust is positively associated with brand switching intention, we also argue that consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with brand switching intention through the mediating effect of platform trust.

Hypothesis 4b.

Through the mediating effect of platform trust, consumer satisfaction will be positively associated with brand switching intention.

2.5. Moderating Effect of Variety Seeking

Variety seeking is the individual tendency to seek different choices of goods or services [15,37]. Variety seeking is not only the behavioral result of consumer dissatisfaction, competitors’ promotion, or negative word-of mouth, but also an intrinsic desire to change [46,47]. Consumers usually desire trying various goods and services to enrich and improve their consumption experiences, but there are individual differences in this tendency [47,48]. A previous study found that the personality trait of variety seeking negatively moderates the relationship between brand trust and brand loyalty in the common purchasing context [48]. Consumers with a lower need for variety would be more loyal to the brands they trust. They have little interest in exploring new brands and hate the uncertainties embedded. They tend to rely on the familiar brands unless they are proved to be untrustworthy. In contrast, those who have a greater need for variety believe new products and new brands bring new experiences, which are of greater joy to them [45]. They are eager to try new brands even though the current brand is trustworthy. Even if they have switched to other brands, it does not necessarily mean that they are not satisfied; instead, they may keep spreading positive word about the current brand and repurchase it later [18,49]. Therefore, we argue that variety seeking weakens the negative relationship between brand trust and brand switching intention and weakens the mediating effect of brand trust. Thus, we propose the following two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 5a.

Variety seeking negatively moderates the relationship between brand trust and brand switching intention such that the negative relationship is weaker at higher levels of variety seeking.

Hypothesis 5b.

Variety seeking negatively moderates the mediating effect of brand trust in the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention such that the negative mediating effect is weaker at higher levels of variety seeking.

The most distinctive and attractive advantage of sharing apparel platforms is that they provide all kinds of apparels, from luxury brands to fast fashion brands, from mass brands to niche brands, from successful brands to emerging brands [1,2,6]. The various brands and plentiful apparels provide opportunities for consumers to seek variety. As argued before, brand switching may be more common in the context of sharing apparel because these consumers usually wish to try different apparels. However, there are still individual differences among them. Trust in the platform assures that all brands are of little risk and makes them more adventurous to try [31,32]. However, only those who have higher variety seeking will make the best of the abundant choices provided by the sharing apparel platform [20,48]. Those with lower variety seeking have little desire to explore new brands even if there is little risk [15,46]. Continued renting of the current brand is convenient and totally free of worry. Consumers with lower variety seeking may be more addicted to the brands they trust and refuse to try new brands [47,48]. Therefore, we argue that variety seeking strengthens the relationship between platform trust and brand switching intention and strengthens the mediating effect of platform trust. Thus, we propose the following two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 6a.

Variety seeking positively moderates the relationship between platform trust and brand switching intention such that the positive relationship is stronger at higher levels of variety seeking.

Hypothesis 6b.

Variety seeking positively moderates the mediating effect of platform trust in the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention such that the positive mediating effect is stronger at higher levels of variety seeking.

The research framework and hypotheses are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework and hypotheses.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

A questionnaire survey was carried out in China. To make sure the participants understood the questionnaire, only those with experience in sharing apparel were surveyed. Participants were asked to report their last consumption of sharing apparel and answer the questions based on this experience. As most consumers of sharing apparel are female, only female consumers were included. To reach as many and as varied participants as possible, we conducted an online survey and invited participants by sending private messages to users on sharing apparel platforms, bloggers on Weibo, and friends on WeChat. A simple but clear explanation was given at the top of the questionnaire to inform the participants of the purpose of the study and promised them that the survey was anonymous and the result would only be used for academic purposes. Participants were also informed that they were free to withdraw at any time.

A total of 384 participants were surveyed, and 346 valid responses were obtained after deleting the unqualified questionnaires, such as those that were finished in less than 2 min (effective response rate of 90.1%). Of the respondents, 56 (16.2%) were aged 22 or younger, 107 (30.9%) were aged between 23 and 25, 127 (36.7%) were aged between 26 and 30, and 56 (16.2%) were aged 31 or older. As for education, 83 (24.0%) had a college degree or lower level of education, 146 (42.2%) had a bachelor’s degree, 82 (23.7%) had a master’s degree, and 35 (10.1%) had a doctorate. As for household income, 56 (16.2%) had an annual household income of less than USD 10,000, 81 (23.4%) between USD 10,001 and 20,000, 136 (39.3%) between USD 20,001 and 30,000, and 73 (21.1%) more than USD 30,000.

3.2. Measures

All the variables were measured with mature scales developed and validated by previous studies or an adaption of such scales to fit the research context. As the study was conducted in China, the items were translated into Chinese through the back-translation process to ensure equivalence between the translation and original items. All the scales were measured with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Consumer satisfaction. Consumer satisfaction of sharing apparel is quite different from that of common purchasing context. To fit the research context, we adapted four items from the satisfaction scales developed for common goods and e-commerce [27,29,50]. One sample item is “The apparels I rent meet my expectations.” Cronbach’s α was 0.85 in this study.

Brand trust. Brand trust was measured with Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s four-item scale [10]. One sample item is “I rely on this brand.” Cronbach’s α was 0.86 in this study.

Platform trust. The sharing apparel platform is quite different from the C2C e-commerce platform, P2P lending platform, social media platforms, and P2P e-commerce platform. Therefore, we adapted four items from previous studies to fit the context of the sharing apparel platform [29,32,34]. One sample item is “This platform acts on behalf of its members.” Cronbach’s α was 0.87 in this study.

Variety seeking. Variety seeking was measured with Menidjel et al.’s seven-item scale [48]. One sample item is “I frequently look for new brands.” Cronbach’s α was 0.89 in this study.

Brand switching intention. To fit the research context of sharing apparel, we adapted four items from previous studies [8,37,45]. One sample item is “I will choose a new brand next time I need to rent apparel.” Cronbach’s α was 0.84 in this study.

Control variables. As suggested by previous studies, consumers of younger age, higher education level or higher household income are more likely to seek variety and switch to new brands; therefore, age, education, and household income were chosen as control variables [8,26,35].

3.3. Common Method Bias

As all variables were measured with self-reported responses from the same group of participants at the same time, the data may suffer from the problem of common method bias [51]. Three steps were taken to eliminate the interference of potential common method bias [52]. First, all variables were measured with mature scales, and items were kept simple and specific in translation to avoid ambiguity. Second, the survey was anonymous, and explanation was given at the top of the questionnaire to encourage participants to answer truthfully. Third, samples with contradictions in the answers and those that were finished in less than 2 min were deleted. A reverse item was included in the scale to check whether the participants answered truthfully. As most participants spent about 3–4 min to finish the questionnaire, it is reasonable to believe that the participants did not take the survey seriously if they finished the questionnaire in less than 2 min. In addition, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to check whether the common method bias was severe. Five factors were extracted in the Exploratory Factor Analysis of all items, with 67.395% variance explained in total. The amount of variance explained by the first factor was 20.608%, which is lower than the critical criterion of 40% and indicates that the common method bias was not severe. This study contains positive effects, negative effects, and moderating effects, which make the results less likely to be interfered with by common method bias than those that contain only positive or negative effects [53].

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validation

First, the results of a model comparison of Confirmatory Factor Analysis showed that the five-factor model had the best fit with the data, as presented in Table 1. For the five-factor model, the standardized regression weight (SRW), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) are presented in Table 2. The SRW values were all higher than or close to 0.70, the CR values were all higher than 0.80, and the AVE values were all higher than 0.50. As presented in Table 3, the square roots of AVE were all larger than the corresponding inter-variable correlations. Thus, the construct validities and discriminant validities were acceptable. Second, as reported previously, Cronbach’s α of all scales exceeded 0.80. Thus, the internal reliabilities were acceptable.

Table 1.

Model comparison of Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 2.

Items, standardized regression weight, composite reliability, and average variance extracted.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and square roots of AVE.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and square roots of AVE are presented in Table 3. Consumer satisfaction was positively correlated with both brand trust (r = 0.276, p < 0.01) and platform trust (r = 0.347, p < 0.01) but wasnot significantly correlated with brand switching intention (r = 0.014, p > 0.05). Brand trust was negatively correlated with brand switching intention (r = −0.267, p < 0.01), while platform trust was positively correlated with brand switching intention (r = 0.202, p < 0.01). In addition, variety seeking was also positively correlated with brand switching intention (r = 0.189, p < 0.01).

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

The hypotheses were tested with OLS regression. A moderated mediation model was constructed and tested with the bootstrapping method using the PROCESS V4.0 developed by Hayes in the SPSS. We first chose the “Model 4” in the PROCESS to test the mediating effects and then chose the “Model 14” to test the moderated mediating effects. We set the confidence level as 95%, set the sampling size of bootstrapping as 5000, chose “-S.D., Mean, +S.D.” as conditional values, took brand switching intention as the dependent variable, took age, education, and household income as control variables, took consumer satisfaction as independent variable, took brand trust and platform trust as mediating variables, took variety seeking as moderating variable, and run the program. The variables were computed and standardized in advance. The results are presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Results of regression analysis.

Table 5.

Results of mediating effect testing.

Table 6.

Results of moderated mediating effect testing.

As presented in Table 4, the results of Model 1 showed that consumer satisfaction was significantly and positively associated with brand trust (β = 0.2243, p < 0.001); Hypothesis 1 was supported. The results of Model 2 showed that consumer satisfaction was significantly and positively associated with platform trust (β = 0.3846, p < 0.001); Hypothesis 2 was also supported. The results of Model 3 showed that brand trust was significantly and negatively associated with brand switching intention (β = −0.2909, p < 0.001), while platform trust was significantly and positively associated with brand switching intention (β = 0.2217, p < 0.001); both Hypothesis 3a and Hypothesis 4a were supported. The results of Model 4 showed that the interaction of brand trust and variety seeking was not significantly associated with brand switching intention (β = 0.0964, p > 0.05), while the interaction of platform trust and variety seeking was significantly and positively associated with brand switching intention (β = 0.1228, p < 0.05); thus, Hypothesis 5a was not supported, and Hypothesis 6a was supported.

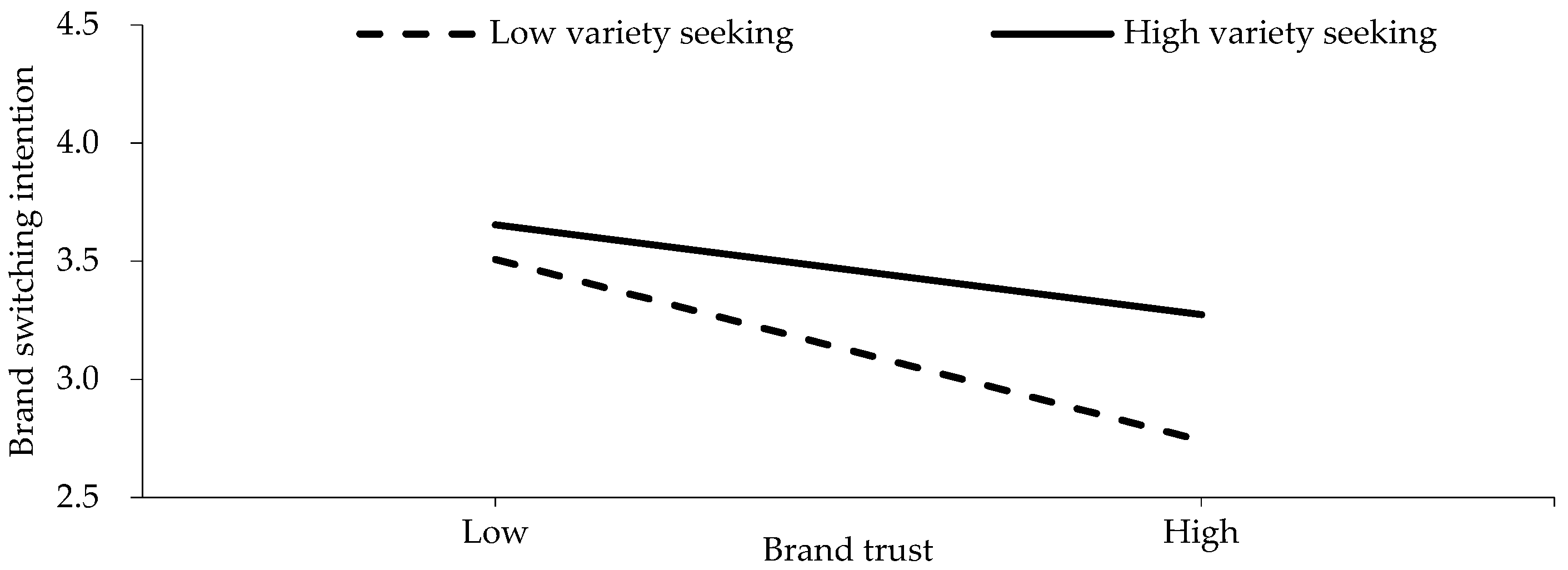

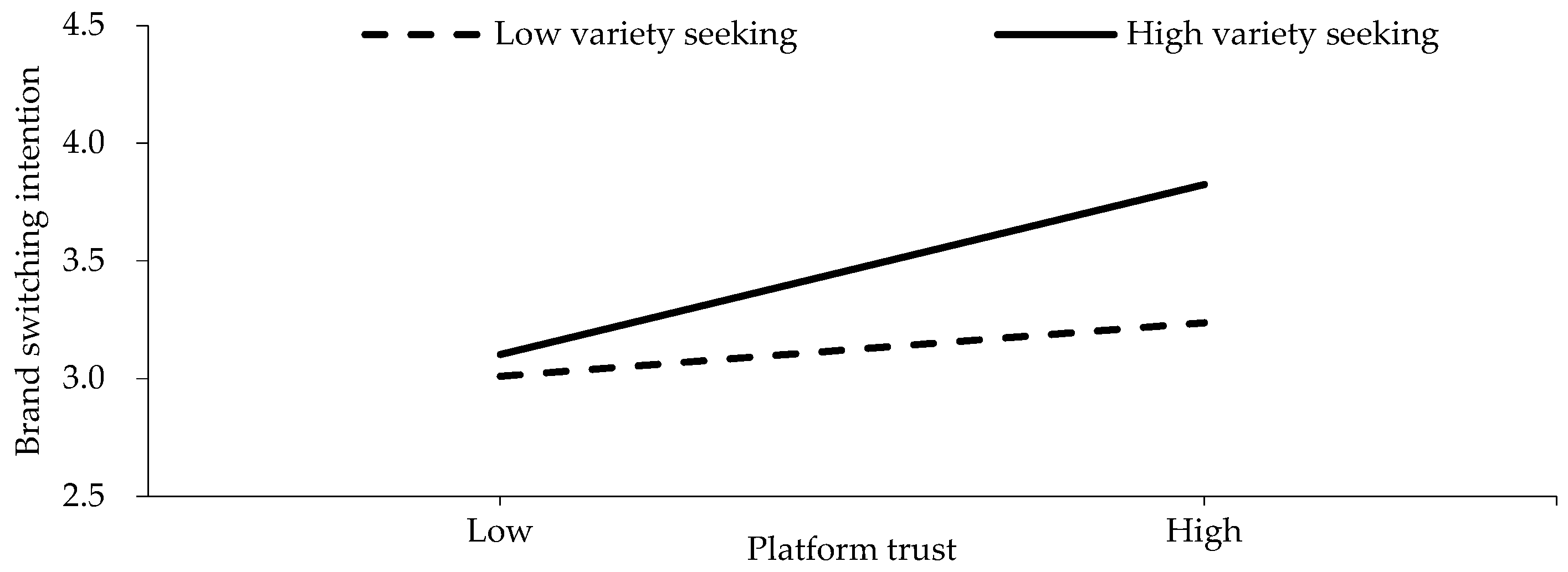

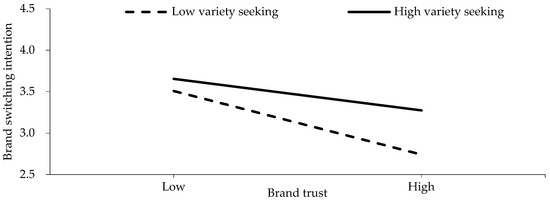

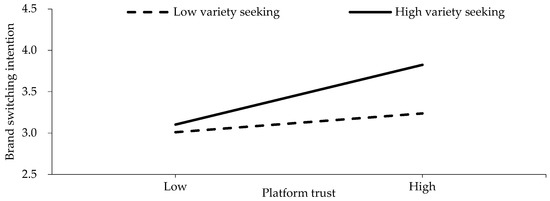

To illuminate the moderating effects of variety seeking, the samples were separated into two groups (Mean + S.D., Mean—S.D.) for further regression analysis. As shown in Figure 2, even though the interaction of brand trust and variety seeking was not significantly associated with brand switching intention, the negative effect of brand trust on brand switching intention was slightly stronger for the low variety-seeking group. In fact, the p-value of the coefficient of the interaction was 0.0574, which is very close to 0.05. In comparison, as shown in Figure 3, the positive effect of platform trust on brand switching intention was stronger for the high variety-seeking group, which provides further support for Hypothesis 6a.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of variety seeking in the relationship between brand trust and brand switching intention.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of variety seeking in the relationship between platform trust and brand switching intention.

As presented in Table 5, the index of the mediating effect of brand trust on the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention was −0.0652, and the 95% confidence interval was [−0.1086, −0.0293], which did not include zero. Therefore, the mediating effect of brand trust was significantly negative, and Hypothesis 3b was supported. The index of the mediating effect of platform trust on the relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand switching intention was 0.0853, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.0403, 0.1361], which did not include zero. Therefore, the mediating effect of platform trust was significantly positive, and Hypothesis 4b was supported.

As presented in Table 6, the index of the difference in the mediating effect of brand trust on different levels of variety seeking was 0.0216, and the 95% confidence interval was [−0.0002, 0.0478], which included zero. Therefore, the moderated mediating effect of brand trust was not significant, and Hypothesis 5b was not supported. The index of the difference in the mediating effect of platform trust on different levels of variety seeking was 0.0472, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.0108, 0.0882], which did not include zero. Therefore, the moderated mediating effect of platform trust was significantly positive, and Hypothesis 6b was supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study aimed to investigate the effect of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention of sharing apparel and to reveal the mechanism by comparing the two different mediating effects of brand trust and platform trust, integrating the moderating effect of variety seeking. Ten hypotheses were put forward, and eight of them were supported. Both Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 were supported, which indicates that consumer satisfaction not only facilitates brand trust but also facilitates platform trust. These findings provide further support for the double attributes of sharing apparel—it is not only consumption of the products produced by the brand but also consumption of the services provided by the platform. Hypothesis 3a was supported, which is consistent with the traditional theories that brand trust reduces brand switching intention. The more insightful result is that Hypothesis 4a was also supported, which indicates that platform trust promotes brand switching intention. Furthermore, Hypothesis 3b and Hypothesis 4b were both supported. This is noteworthy because it provided evidence for the dual effects of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention. Even though the overall effect of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention was not significant, it negatively influenced brand switching intention through the mediating effect of brand trust and positively influenced brand switching intention through the mediating effect of platform trust. As for the moderating effect of variety seeking, Hypothesis 6a and Hypothesis 6b were also supported. The positive effect of platform trust on brand switching intention and the mediating effect of platform trust were both stronger for consumers with high variety seeking. It is a pity that Hypothesis 5a and Hypothesis 5b were not supported. The negative effect of brand trust on brand switching intention and the mediating effect of brand trust were homogeneous for consumers with different levels of variety seeking. The possible reason may be that the moderating effect of variety seeking on brand trust and brand switching intention only exists with all kinds of brands taken into consideration. However, in the context of sharing apparel, most of the brands are premium brands. Consumers may be more loyalty to premium brands than to mass brands because there are many substitutes for mass brands. As the data contained only consumers of premiums brands, the effect of brand trust on brand switching intention will always be strongly negative, irrespective of how we separate them into groups. Therefore, even for the high variety-seeking group, the negative effect of brand trust was also strong (β = −0.1886, p < 0.05), leaving little room for it to be significantly different from the low variety-seeking group (β = −0.3815, p < 0.001). The lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval of the differences were −0.0031 and −0.0002, which are very close to zero, implying that the moderating effect and the moderated mediating effect were very close to being significant.

Based on these findings, this study has made several contributions to the theories. First, this study has demonstrated that consumer satisfaction promotes platform trust as well as brand trust, which is new and enriches the theory of consumer satisfaction [40,50]. In the context of sharing apparel, consumers not only receive apparels from the brand but also experience services from the platform, which are two sources of consumer satisfaction and lead to the two kinds of trust. It also enlightens the possibility to separate consumer satisfaction into two subdimensions, such as product satisfaction (brand-related satisfaction) and service satisfaction (platform-related satisfaction). Second, this study has also demonstrated that consumer satisfaction facilitates brand switching intention through the mediating effect of platform trust, which is totally different from the traditional view that consumer satisfaction simply reduces brand switching intention [7,27,40]. However, we have to admit that it is not a contradiction with, but a supplement to the traditional theories. Consumers who switch to other brands are not avoiding the platform; instead, they may increase their consumption on the platform. Therefore, the logic of the positive mediating effect of platform trust and the negative mediating effect of brand trust is actually the same. These novel insights not only enrich the existent theories but also show that the traditional theories may not be effective in the context of sharing economy and call for further research with new perspectives. Third, by investigating the moderating effect of variety seeking, this study has identified the boundary conditions of the effect of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention. These findings integrate the theories of consumer satisfaction, brand trust, platform trust, variety seeking, and brand switching intention and help to understand the intricate relationships among them. Last but not least, most previous studies on sharing economy focused on consumers or the platform [2,40], while this study included a third actor of the brands and helps to understand the interactions among the platform, brands, and consumers comprehensively. This may help to explain why some brands refused to cooperated with sharing apparel platforms, revealing the flaws in the business model of sharing apparel.

5.2. Managerial Implications

There are also some managerial implications derived from the findings. First, since brand switching is a basic need for consumers, especially for those with high variety seeking, sharing apparel platforms should expand their categories and brands instead of providing only a few premium brands. Second, as consumer satisfaction may promote platform trust and encourage consumers to use other brands, platforms could attract consumers by subsidizing some high-quality premium brands and enlarge their revenue and profit with other favorable niche brands. They could even create and promote their own private brand on the sharing apparel platform and introduce it to retailing when it gains enough popularity. The most important thing to keep in mind is that the quality of all of their apparels must be guaranteed to avoid destroying consumers’ trust in the platform. Third, for premium brands, even though cooperating with sharing platforms may increase their exposure to young consumers, they should also be cautious about fostering potential competitors. Fourth, for emerging brands, gaining their first users is extremely difficult, and cooperating with sharing apparel platforms may help them to be accepted more easily.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

There are also some limitations of this study. First, even though our hypothesis were developed on the basis of rigorous theoretical analysis, the cross-sectional design limits the causality of the findings. The cross-sectional design also suffers from potential common method bias. Even though several steps were taken to ease the problem, adding a marker variable in the survey will help to further test whether the common method bias is severe. Of course, a longitudinal design or experimental design will be preferred. Second, as we used a self-reported questionnaire, the data may depart from the reality because of the problems in the scales, translations, and socially desirable responses. Even though mature scales, back-translation, and the promise of confidentiality may ease these problems, secondary data of consumption records and text analysis of online comments will be more objective and accurate. Third, constrained by the resources, convenient sampling was used in this study, and the sampling size was very small. The results may be subject to sampling bias, which may be another possible reason why Hypothesis 5a and Hypothesis 5b were not supported. Random sampling or a larger sample size will help to eliminate the instability of the results and strengthen the generalizability of the conclusions. Fourth, this study argued the double attributes of sharing apparel (not only consumption of the products produced by the brand but also consumption of the services provided by the platform) and found the dual effects of consumer satisfaction. These results also suggest that there may be subdimensions of consumer satisfaction of sharing apparel, such as product satisfaction (brand-related satisfaction) and service satisfaction (platform-related satisfaction). Digging into the subdimensions of consumer satisfaction may help to further explain the dual effects on brand switching intention. Fifth, this study explored individual differences in variety seeking. However, the practical implications are quite limited since the individual characteristics cannot be manipulated. Future studies on other contextual factors, such as brand types, platform marketing strategies, or legal regulations, will be very interesting and inspiring.

6. Conclusions

To sum up, this study has demonstrated that consumer satisfaction associated with sharing apparel facilitates both brand trust and platform trust, and brand trust reduces brand switching intention while platform trust facilitates brand switching intention. Therefore, there are dual effects of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention of sharing apparel through the opposite mediating effects of brand trust and platform trust. In addition, consumers’ variety seeking moderates the relationship between platform trust and brand switching intention, such that the positive effect is stronger at higher levels of variety seeking. Correspondingly, the mediating effect of platform trust is also stronger at higher levels of variety seeking. Based on these findings, we recommend that sharing apparel platforms could enlarge their revenue and profit by fostering emerging brands or private brands, while premium brands should be more cautious about fostering potential competitors when cooperating with sharing platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and Z.X.; methodology, Y.W. and Z.X.; formal analysis, Y.W. and Z.X.; investigation, Y.W.; resources, Y.W. and Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and Z.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.X.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, Z.X.; funding acquisition, Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (22NDJC014Z), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ22G020006), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72101233), and Research Projects of the Department of Education of Zhejiang Province (Y202045242).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Niinimäki, K. Clothes sharing in cities: The case of fashion leasing. In A Modern Guide to the Urban Sharing Economy; Sigler, T., Corcoran, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Factors explaining shared clothes consumption in China: Individual benefit or planet concern? Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24, e1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner Armstrong, C.M.; Park, H. Sustainability and collaborative apparel consumption: Putting the digital ‘sharing’ economy under the microscope. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Joyner Armstrong, C.M. Collaborative apparel consumption in the digital sharing economy: An agenda for academic inquiry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Joyner Armstrong, C.M. Will “no-ownership” work for apparel?: Implications for apparel retailers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L.; Wang, Y.; Chi, T. Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Carrero, M. The mediating effect of satisfaction on consumers’ switching intention. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasrodashti, E.K. Explaining brand switching behavior using pull–push–mooring theory and the theory of reasoned action. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, S.M.; Sangari, M.S.; Keramati, A. An integrative framework for customer switching behavior. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 1067–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villagra, N.; Monfort, A.; Sánchez Herrera, J. The mediating role of brand trust in the relationship between brand personality and brand loyalty. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedova, A.; Vila-Brunet, N.; Mas-Machuca, M. Building trust in sharing economy platforms: Trust antecedents and their configurations. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 1463–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huurne, M.T.; Ronteltap, A.; Corten, R.; Buskens, V. Antecedents of trust in the sharing economy: A systematic review. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.E. Consumer variety-seeking among goods and services: An integrative review. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 1995, 2, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O.; Tudoran, A.A.; Honkanen, P.; Verplanken, B. Differences and similarities between impulse buying and variety seeking: A personality-based perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baltas, G.; Kokkinaki, F.; Loukopoulou, A. Does variety seeking vary between hedonic and utilitarian products? The role of attribute type. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. Why do satisfied customers switch? Focus on the restaurant patron variety-seeking orientation and purchase decision involvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belver-Delgado, T.; San-Martín, S.; Hernández-Maestro, R.M. The influence of website quality and star rating signals on booking intention: Analyzing the moderating effect of variety seeking. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2020, 25, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.; Villaseñor, N.; Yagüe, M.J. Customer’s loyalty and trial intentions within the retailer: The moderating role of variety-seeking tendency. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, J.L.; Cote, J.A. Defining consumer satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2000, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyari, H.; Abareshi, A. Consumer satisfaction in social commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Dev. Areas 2018, 52, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Alemán, J.L. Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2005, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khadim, R.A.; Hanan, M.A.; Arshad, A.; Saleem, N.; Khadim, N.A. Revisiting antecedents of brand loyalty: Impact of perceived social media communication with brand trust and brand equity as mediators. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huaman-Ramirez, R.; Merunka, D. Brand experience effects on brand attachment: The role of brand trust, age, and income. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 610–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zboja, J.J.; Voorhees, C.M. The impact of brand trust and satisfaction on retailer repurchase intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Santini, F.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sampaio, C.H.; Pinto, D.C. The brand experience extended model: A meta-analysis. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, L.; Hayes, L.A. How do technology readiness, platform functionality and trust influence C2C user satisfaction? J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.; Qu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H. Platform trust in C2C e-commerce platform: The sellers’ cultural perspective. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Lin, X. The Research on the influencing factors of trust in online P2P lending: Based on platform. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference, Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.; Li, S.Y.; Tse, D.K. Interpersonal trust and platform credibility in a Chinese multibrand online community. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geng, S.; Yang, P.; Gao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yang, C. The effects of ad social and personal relevance on consumer ad engagement on social media: The moderating role of platform trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallem, Y.; Abbes, I.; Hikkerova, L.; Taga, M.P.N. A trust model for collaborative redistribution platforms: A platform design issue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 170, 120943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.W.Y.; Chan, T.K.H.; Balaji, M.S.; Chong, A.Y.L. Why people participate in the sharing economy: An empirical investigation of Uber. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, T.; Hawlitschek, F.; Adam, M.T. Reputation transfer. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2019, 61, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Wei, C.F.; Tseng, L.Y.; Cheng, C.C. What drives green brand switching behavior? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.S.; Rita, P.; Santos, Z.R. On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Bidmon, S. Risk aversion and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand trust and brand affect. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, A. Perceived quality, brand image and brand trust as determinants of brand loyalty. J. Res. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, S.; Banerjee, S. On the relationship between brand scandal and consumer attitudes: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 45, 1047–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.P.; Nguyen, N.H. The impact of corporate social responsibility and customer trust on the relationship between website information quality and customer loyalty in e-tailing context. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2020, 14, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; Xue, F.; Zhao, J. What happens when satisfied customers need variety?—Effects of purchase decision involvement and product category on Chinese consumers’ brand-switching behavior. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2018, 30, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Giering, A. Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty? An empirical analysis. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 18, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.K.; Trivedi, M. Do consumer perceptions matter in measuring choice variety and variety seeking? J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2786–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menidjel, C.; Benhabib, A.; Bilgihan, A. Examining the moderating role of personality traits in the relationship between brand trust and brand loyalty. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C. Are variety-seekers bad customers? An analysis of the role of recommendations in the service profit chain. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2006, 4, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Du, R.; Olsen, T. Feedback mechanisms and consumer satisfaction, trust and repurchase intention in online retail. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2018, 35, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Huo, Y. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Testing a moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.; Oliveira, P. Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).