When Digital Mass Participation Meets Citizen Deliberation: Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Climate Policy-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mini-Publics and Maxi-Publics: Strengths and Weaknesses

2.1. Mini-Publics: “Catching the Wave” of Climate Assemblies

| Ideal 1: Politically independent | Practice 1: Organizational flaws |

| Ref. [24] suggests organizing climate mini-publics by actors other than governments, industries, or activists, which have no interest in the issue itself. The Irish Climate assembly case is an example with a truly “apolitical” and “independent” status, with the Supreme Court at the center stage. The Danish Board of Technology recruited partner organizations that were “unbiased with regards to climate change” [25], and the New South Wales energy-related mini-public was triggered by a bipartisan parliamentary committee [26]. | Refs. [27,28,29] acknowledge that mini-publics are frequently too “tightly coupled” with governmental bodies; and that their “scrutinizing role” is limited. Critics also point to the example of how the steering body of the French Climate Assembly converted into a “politicized” forum and was likely to be associated with the ideals of those who initiated them [28,30]. Furthermore, climate mini-publics may encounter opposition once they aim to take a powerful place in political decision-making e.g., in Belgium [31]. |

| Ideal 2: Demographic representation | Practice 2: Unequal representation |

| Random selection of citizens in a climate assembly is what delivers the “mini-public” and enforces the principle of equality [10]. It is not only important to be demographically representative but also that the broadest possible range of views from society is present [32]. Barriers to participation can be removed through reimbursement or child care and more intensive guidance and support for participants. Social workers and community organizations can play a role in recruiting low-literacy and other harder-to-reach groups. Additionally, criteria such as “views on climate change” or questions on online behavior can be used to prevent the over-representation of certain groups [33]. | As [34] shows, despite operating from a principle of inclusion and representation, climate assemblies can produce underrepresentation among the group with migration background, as well as among those with lower education, and in the age group 18–34, mostly who do not follow-up an invitation to participate [35]. Minors are often not allowed to participate too. Recent experience shows that the response rate by drawing by lot is between 2% and 5% [21]. Considerations have to be made regarding access and supervision (e.g., for minors or disabled) in order to reduce participation hurdles [10] or whether efforts should be made to reach out and oversample traditionally excluded communities to uphold the principle of equity. Further possibilities are reserving seats in the assembly for elected representatives or affected citizens who were not chosen by the lot. |

| Ideal 3: Deliberative quality | Practice 3: One-sided problem framing |

| Ideally, during the deliberative sessions members gain more knowledge about the issue partly by engaging with each other and thereby understanding different perspectives with the help of a neutral facilitator, and partly by hearing from experts and witnesses. As the authors of [10] recommend, there should be initially agreed upon guidelines on how the most suitable experts for the topic are being selected, how they present their information, and how the independence of the experts, or in the case of contested topics, how the provision of balanced information is guaranteed. | Critics caution that climate assemblies can unintentionally close down public debates. They may actually strengthen pre-existing (unconscious) biases, i.e., prejudice based on gender, ethnicity, race, or class [36]. They may frame the problems in line with the culture of the organizing body [37], or favor repeated expert statements [38], which limits the terms of citizens’ engagement and public scrutiny. Ref. [30] observed tendencies in the French Climate Assembly to rely on a group of “internal experts”, working for agencies, state-related institutes, and businesses. Some of these “experts” were repeatedly telling citizens what to propose. This procedural flaw was further augmented by the fact that various speakers had unequal speaking times, ranging from 50 min for a representative of the Ministry of Ecology to 5 minutes for an NGO [30]. |

| Ideal 4: Enabling a connection with the rest of the society | Practice 4: Lack of connection to the rest of the society |

| Since climate assemblies are micropolitical processes that are a part of a broader political system, the authors of [10] recommend that mini-publics procedures and outputs must be at least open to public scrutiny (e.g., through live broadcasting, public sessions, etc.) and time should be set aside to connect or validate their preliminary findings with those outside the mini-public itself, i.e., to involve the maxi-public after the mini-public has come to their initial, preliminary findings. Climate assemblies may also be seen as a new channel to communicate sustainable policies to the broader population to garner public support [39]. | In practice, climate mini-publics can become ingroups with their own biases. Members can come to believe that the public “will not understand the proposals because they have not spent nine months working on them” [30]. There is empirical evidence that participants from the wider public process objective information provided from a mini-public quite differently than the members of this mini-public. In some cases, it dampens their factual knowledge, but it has also been shown to positively increase people’s empathy towards the other side [40]. Moreover, using climate assemblies instrumentally to garner support may lead to cherry-picking of results [29]. |

| Ideal 5: Political uptake of the mini-publics recommendations | Practice 5: No or low uptake of the mini-publics recommendations |

| According to the authors of [41], governments that engage their citizens through deliberative processes seem to be widely supported by their residents. Moreover, many citizens engage in deliberation exactly because they are designed for those frustrated with status quo politics [42]. To minimize risks of tokenistic procedures, there is a need to transparently define at the design stage how the mini-publics proposals will be dealt with in the political system, i.e., if they are of consultative character, have a more binding status, or are submitted to a popular vote [10,13]. | Refs. [29,31] provide evidence about the inherent lack of incentives for elected representatives to consider the recommendations put forward by mini-publics. In other cases, climate assemblies are disbanded before their output is utilized [43]. In the UK, the climate assembly is reported to have clashed with the parliamentary system [44]. In France, President Macron initially promised that all proposals would be forwarded to parliament “without filter”. However, Macron backtracked from his promises months later. In the end, only 10% of the recommendations of the French Citizens’ Assembly were adopted by the government unchanged, while 37% were modified, and 53% were rejected, stirring frustration among participants [45]. Yet, besides lobbying efforts, the low adoption rate is also attributed to missing legal and financial checks, making the proposals unfit for implementation [46]. |

2.2. Maxi-Publics: Making Digital Participation Work for the Many

2.3. Maxi-Publics: Downsides Common to Maxi-Publics in Practice

| Mini-Publics (e.g., Climate Assembly) | Maxi-Publics (e.g., Online Participation) | |

|---|---|---|

| Function | Establishing a high-quality discourse between a small group of selected representative citizens to formulate policy recommendations. | Providing access to larger groups of citizens to express ideas on policy recommendations and to aggregate preferences of the wider public. |

| Intensity (duration; budget) | Participant selection is time-intensive. Several days/weekends over the course of multiple months; costs vary between local (EUR 50,000–100,000) and national assemblies (EUR 2–5 million Euro) and demand an intense commitment. | Duration of process: 4–6 weeks; duration for participants: 20–40 min. Costs vary from around 25,000 to 50,000—asks medium intense commitment from both participants and organizers. |

| Participatory inclusion | Exclusive (20–250), randomly selected group of citizens. Every participant has the same chance to be selected. Motivated and interested citizens cannot participate. The deliberative experience stays within this mini-public. | Inclusive. All citizens can theoretically participate. Making participation relevant and easy to access is imperative, that participation is possible for all kinds of citizens. |

| Demographic representation | Participants are selected to match demographic quotas. Underrepresentation can still occur due to trade-offs between relative small-n (participants) and high-p (selection variables) Lower educated and those who do not like to speak in public to participate often decline invitations. Those under 18 are usually not represented. | Self-selection bias is very likely to occur. A combination with a sizable representative sample is recommended. Datasets can be reweighted so that the distributions of the demographic variables of each sample match the corresponding population distributions. |

| Expert information | Focus on expert and “political” knowledge in assembly hearings and support bodies of the assembly. Rigid procedures can reduce flaws in information provision and guarantee fair and balanced hearings. | No official hearings. The policy options, the range of their impacts, and constraints are predetermined by a range of relevant experts and policy-makers beforehand and/or co-created with citizens. |

| Deliberative quality | Trained moderators facilitate the deliberation and help in sorting opinions and arguments. By explaining views, asking questions, or jointly weighing considerations, deliberation increases the ability and willingness to deal with issue complexity and can reduce polarization. Deliberative mini-publics produce higher quality policy measures. | The quality of preferences that people express is lower than those expressed after deliberation. Often there is no human moderator available. Participants need to be stimulated to deliberate within themselves. Maxi-publics produce a higher quantity of awareness over the impacts of policy measures in society. |

| Output | Decision-making is often done by majority voting in the assembly. | Aggregated and clustered presentation of individual preferences. |

3. Methodological Approach of the Study

3.1. Combining Online Mass Participation with Deliberative Mini-Publics

- (1)

- Participatory inclusion: Mini- and maxi-publics combine an intensive participation procedure that is suitable for an exclusive group of citizens with a less intensive one that is preferred by a larger group in society.

- (2)

- Demographic representation: Through different selection and statistical reweighting processes, both systems together can reduce shortcomings of representativeness (to make sure the participants in the mini-public and the maxi-public are a good proxy for the public at large).

- (3)

- Expert information: The provision of expert information can be more balanced, not only predetermined in expert framings of problems, but rather in increasing the number of “witnesses” and “small voices” that would otherwise not be heard.

- (4)

- Deliberative quality: A combination can increase the substantive quality of policy proposals, through deliberating about the pros and cons of different proposals in the mini-public, on the one hand, and with crowdsourcing additional ideas and public considerations on the other hand.

- (5)

- Political uptake: Since the recommendations of the mini-public are backed by their consultation of the maxi-public, therefore, the incentives for elected representatives to consider the recommendations increase.

- (6)

- Acceptability: A combination can increase the acceptability of policy recommendations by non-participants (those who were not able to participate in either a mini- or maxi-public).

4. The Combination of Mini- and Maxi-Publics to Decide on a Future Energy Strategy

4.1. The First Mini-Public: Defining Future Policy Scenarios

- “The municipality takes the lead and unburdens the public”: The municipality will stay in charge and endorse what residents think is important.

- “The residents do it themselves”: Residents generate their own energy and keep control of everything themselves.

- “The market decides”: The municipality waits and sees what the market comes up with. Market players are obliged to involve the residents in their plans.

- “Large-scale energy generation in a small number of places”: This way the municipality avoids having wind and solar parks in a lot of different places.

- “Focus on storage”: Súdwest-Fryslân will become the Netherlands’ battery and will ensure that the Dutch energy system is stable.

- “Become the energy provider for the Netherlands”: Súdwest-Fryslân will help the rest of the Netherlands to make energy generation more sustainable.

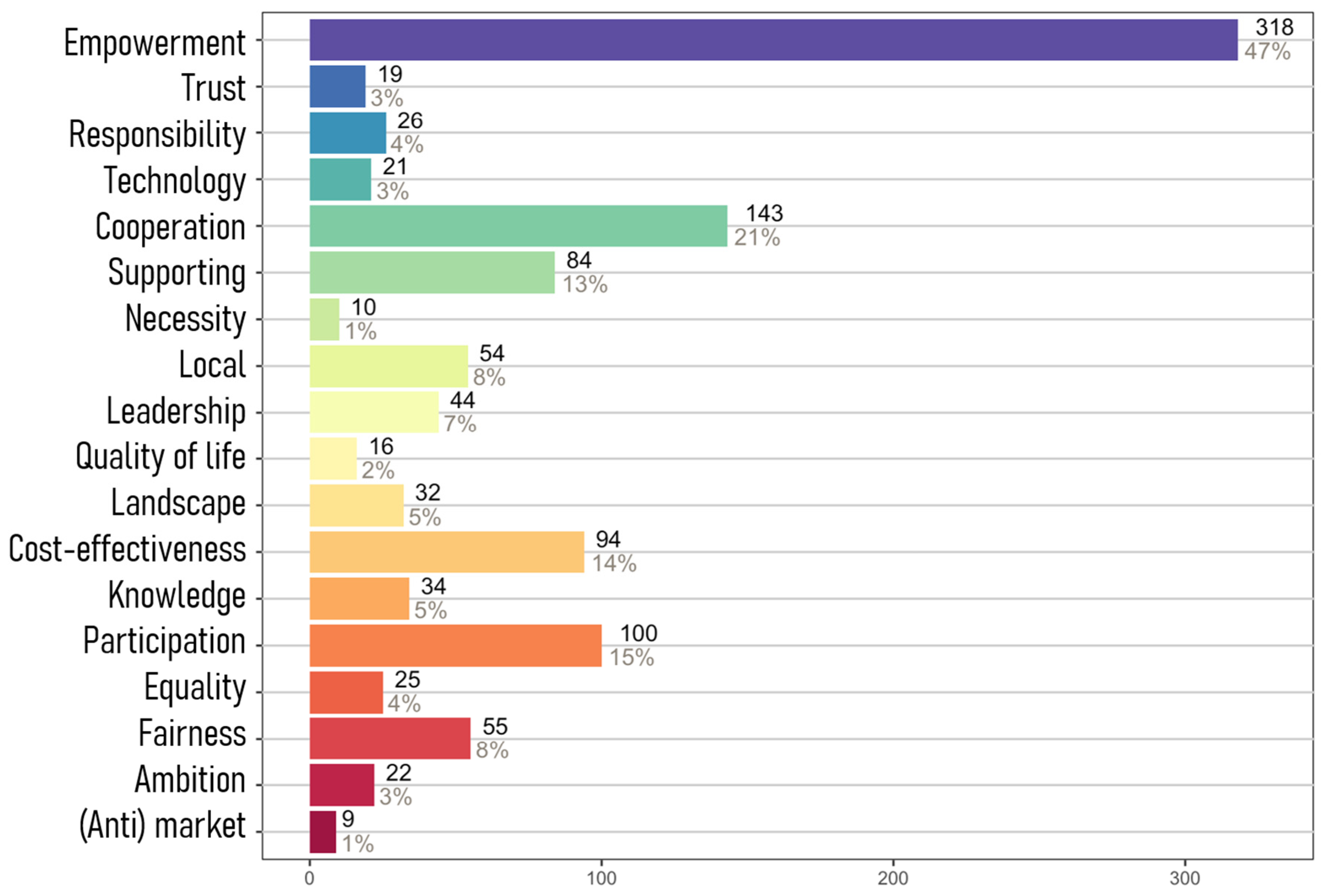

4.2. The Maxi-Public: What Does the Broader Community Think?

4.3. The Second Mini-Public: Interpreting the Results and Formulating Policy Recommendations

4.4. The Political Uptake

5. Experiences of Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Súdwest-Fryslân

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Maxi-Public Recruitment Campaign

Appendix B. The Six Options at Large

Appendix B.1. The Municipality Takes the Lead

- The municipality can help inhabitants who have little to spend and share the profits. This way, people with smaller wallets can also generate sustainable energy.

- The energy needs of all inhabitants of Súdwest-Fryslân are not equal. The municipality will divide the costs and benefits between cities and villages.

- The municipality does not have influence on everything. Energy policy is also steered from the national government in The Hague. Moreover, there is a limited budget. Meaning the municipality cannot protect or help everyone.

- In this way the municipality can keep control over its energy management. Energy becomes a public good again.

Appendix B.2. Residents Do It Themselves

- Residents of neighborhoods and villages are co-owners of local installations. This stimulates the region’s independence in its own energy supply. The money they earn from sustainable energy generation stays in the region.

- A great deal of knowledge and expertise is required to implement sustainable energy projects. That knowledge and skill is not available in every district or village. The municipality will provide support through an energy desk.

- The landscape may become fragmented because local communities are free to choose the technology they use to generate energy.

- It is sometimes very difficult for a village or neighborhood to reach a joint decision. Every house and every street is different, so it can be difficult to find one solution together.

Appendix B.3. The Market Determines

- It is a low-cost option for the inhabitants but the social returns are low. The market does not choose environmentally or socially friendly solutions, but only those that make the most money.

- Companies that spend money on sustainable energy and new technology are rewarded.

- Not all inhabitants of Súdwest-Fryslân can benefit. Small projects by Súdwest-Fryslân residents cannot compete with large companies. Or the companies buy small projects.

- The landscape may become fragmented, because companies come up with their own locations and may choose which technology they use for energy generation. In this way, market parties have more influence on how Súdwest-Fryslân looks than the municipality and residents themselves.

Appendix B.4. Large-Scale Energy Generation in a Small Number of Places

- By stimulating large projects, the municipality will receive a profit. This money can be distributed to the inhabitants. The money can also be used for facilities, for example to keep the swimming pool or the library open, or to make the region more attractive to young people.

- By allowing large wind farms in some places, you can protect the landscape in others.

- Large wind parks and solar parks can have an impact on tourism. Tourists might consider it a detriment to the Frisian landscape.

- People who live near a wind or solar park can experience this as unpleasant due to, for example, noise nuisance, impact shadow and falling house prices.

Appendix B.5. Investing in Storage

- Much innovation is still needed in storage. Some storage options use a lot of raw materials, (neighborhood) batteries and other storage forms such as hydrogen can be dangerous for people in large quantities.

- The obvious solution is to store the energy close to the sustainable energy source or close to the user.

- In this way, the municipality can maintain control over its energy management and play an important role in the energy transition.

Appendix B.6. Become the Energy Supplier of The Netherlands

- Combining various new energy technologies increases the yield of renewable energy.

- Generating sustainable energy is good for the local economy. It creates jobs, companies like to settle in areas with a lot of sustainable energy. At the same time, tourism can be adversely affected.

- The municipality retains control over the generation of energy. The money that Súdwest-Fryslân earns flows directly back to the community.

- People who live close to these industrial energy parks and the IJsselmeer may experience a higher amount of nuisance.

Appendix C. Regression Analysis of Characteristics and Preferences

| Policy Option | Municipality Takes the Lead | Residents Do It Themselves | The Market Decides | Concentration | Storage | Energy Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (f) | 4.539 *** | 1.998 | −3.822 *** | 0.585 | −2.710 *** | 0.950 |

| (1.648) | (1.425) | (1.032) | (1.156) | (0.999) | (0.626) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–25 | 9.129 | 6.592 | −1.597 | −11.179 ** | −5.631 | −1.616 |

| (7.584) | (6.557) | (4.748) | (5.319) | (4.594) | (2.880) | |

| 26–35 | 11.907 * | 12.417 ** | −1.815 | −12.626 *** | −0.862 | −7.544 *** |

| (6.727) | (5.817) | (4.211) | (4.718) | (4.075) | (2.554) | |

| 36–45 | 12.827 ** | 11.409 ** | −2.555 | −10.491 ** | −3.085 | −6.855 *** |

| (6.508) | (5.627) | (4.075) | (4.565) | (3.943) | (2.471) | |

| 46–55 | 10.681 * | 12.009 ** | −2.899 | −10.087 ** | −4.189 | −6.942 *** |

| (6.347) | (5.488) | (3.974) | (4.452) | (3.845) | (2.410) | |

| 56–65 | 13.332 ** | 12.300 ** | −3.439 | −8.611 * | −5.200 | −8.493 *** |

| (6.301) | (5.448) | (3.945) | (4.420) | (3.817) | (2.392) | |

| 66+ | 16.656 *** | 7.991 | −3.127 | −9.228 ** | −7.686 ** | −9.001 *** |

| (6.314) | (5.459) | (3.953) | (4.429) | (3.827) | (2.397) | |

| Education | −1.205 | 0.417 | 1.207 ** | 0.252 | 0.025 | −0.087 |

| (0.765) | (0.661) | (0.479) | (0.536) | (0.464) | (0.290) | |

| Kantar sample | −2.128 | −1.239 | 3.436 * | 2.675 | −0.641 | −0.037 |

| (3.141) | (2.716) | (1.967) | (2.203) | (1.903) | (1.193) | |

| Relation to sustainable energy | ||||||

| Member of a cooperative | −5.420 * | 6.197 ** | −1.594 | 1.639 | 1.617 | 0.004 |

| (3.060) | (2.646) | (1.916) | (2.146) | (1.853) | (1.162) | |

| Green entrepreneur | −3.331 | −1.455 | 3.848 | 1.106 | −2.129 | −0.965 |

| (4.541) | (3.926) | (2.843) | (3.185) | (2.750) | (1.724) | |

| Green energy consumer | 5.267 *** | −2.193 * | −1.561 | 1.121 | −0.911 | 0.295 |

| (1.517) | (1.312) | (0.950) | (1.064) | (0.919) | (0.576) | |

| Has renewables shares | −0.877 | 2.564 | −0.825 | 0.076 | 2.569 | −0.624 |

| (2.748) | (2.376) | (1.721) | (1.928) | (1.664) | (1.044) | |

| Other relationship | −1.099 | 1.921 | −2.062 * | −0.063 | 0.254 | 0.324 |

| (1.768) | (1.529) | (1.107) | (1.240) | (1.072) | (0.671) | |

| Prosumer | −3.152 * | 4.114 *** | −2.494 ** | −2.049 * | 3.975 *** | 0.501 |

| (1.761) | (1.523) | (1.102) | (1.235) | (1.067) | (0.669) | |

| No interest in renewables | −1.089 | −7.615 ** | −0.160 | 2.671 | −3.763 | −2.185 |

| (3.830) | (3.312) | (2.398) | (2.686) | (2.320) | (1.454) | |

| No, but interested | 0.942 | 2.793 | −3.472 ** | −0.840 | 0.633 | 1.108 |

| (2.154) | (1.862) | (1.348) | (1.511) | (1.305) | (0.818) | |

| Postal code area | ||||||

| Urban | 0.049 | −2.282 | −0.431 | 0.493 | −2.505 | −0.856 |

| (6.086) | (5.263) | (3.810) | (4.269) | (3.686) | (2.311) | |

| Lake area | −5.089 | 3.526 | −1.202 | 2.813 | −1.696 | −1.831 |

| (5.709) | (4.936) | (3.574) | (4.004) | (3.457) | (2.168) | |

| Coastal | −1.988 | 8.634 * | −4.491 | −3.017 | −0.797 | −2.767 |

| (5.474) | (4.733) | (3.427) | (3.840) | (3.315) | (2.079) | |

| Windpark area | 0.634 | −7.440 *** | 2.978 | 4.272 * | −0.460 | −0.016 |

| (3.110) | (2.689) | (1.947) | (2.182) | (1.884) | (1.181) | |

| Countryside | −4.511 | 3.267 | −1.446 | −0.220 | −0.983 | −1.664 |

| (6.157) | (5.324) | (3.855) | (4.319) | (3.729) | (2.338) | |

| N | 1149 | 1149 | 1149 | 1149 | 1148 | 1149 |

| r2 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

Appendix D. Experience with PVE—Participant Responses

| The advice of citizens should be decisive | 5% |

| There should be more weight on the advice of citizens than on the advice of experts | 16% |

| There should be equal weight between the advice of citizens and the advice of experts | 53% |

| There should be more weight on the advice of experts than on the advice of citizens | 23% |

| The advice of experts should be decisive | 3% |

- “Some insight into the energy market and the energy transition world is needed to be able to give a well-founded answer. Many individuals do not have this, it would have been better to conduct a good information campaign first.”

- “I personally think that the idea of distributing points is a bit difficult for many people. I would have preferred a more intuitive questionnaire.”

- “I believe that the questions are too complicated for residents with little or no knowledge of the issues and therefore many will drop out and that if they do answer, the answers are based on too little knowledge of the issues and the survey will not give a useful result.”

Appendix E. Examples of Value Maps of the Maxi-Public

Appendix F. Questionnaire to the Policy-Makers, Councilors, Participation Facilitators, and Members of the Mini-Public

- Why was a Participatory Value Evaluation (PVE) consultation combined with a mini-public in which citizens co-developed the PVE and a citizens’ assembly that translated the insights of the PVE into recommendations? What was the reason to choose for multiple methods instead of one method?

- Would you recommend a similar participation process to another municipality? If so, what are your main arguments for recommending such a participatory process?

- What would have gone less well if you had only conducted a PVE consultation?

- What would have gone less well if you had only conducted a citizens’ forum?

- What are the most important points of improvement from the participation process in Súdwest-Fryslân? If we could do it all over again, what would you have done differently?

- Do the advantages of combining a PVE consultation with a citizens’ assembly outweigh the disadvantages? Or do you think, in retrospect, that it would have been better to use one of the two methods of participation or to do something completely different?

References

- Renn, O.; Schweizer, P.J. Inclusive governance for energy policy making: Conceptual foundations, applications, and lessons learned. In The Role of Public Participation in Energy Transitions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichambis, A.C. European Green Deal and Environmental Citizenship: Two Interrelated Concepts. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M.; Lees-Marshment, J. Political Leaders and Public Engagement: The Hidden World of Informal Elite–Citizen Interaction. Polit. Stud. 2019, 67, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudet, H.S. Public Perceptions of and Responses to New Energy Technologies. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itten, A.V. Overcoming Social Division: Conflict Resolution in Times of Polarization and Democratic Disconnection; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, A.; Pidgeon, N. Psychology, Climate Change & Sustainable Bahaviour. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2009, 51, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Community versus Local Energy in a Context of Climate Emergency. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Burningham, K.; Walker, G.; Cass, N. Imagined Publics and Engagement around Renewable Energy Technologies in the UK. Public Underst. Sci. 2010, 21, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, M.V.; Rohleder, N.; Rohner, S.L. Clinical Ecopsychology: The Mental Health Impacts and Underlying Pathways of the Climate and Environmental Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 675936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curato, N.; Farrell, D.; Geissel, B.; Grönlund, K.; Mockler, P.; Pilet, J.B.; Setälä, M. Deliberative Mini-Publics: Core Design Features; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Bächtiger, A.; Chambers, S.; Cohen, J.; Druckman, J.N.; Felicetti, A.; Fishkin, J.S.; Farrell, D.M.; Fung, A.; Gutmann, A.; et al. The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science 2019, 363, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulha, K.; Leino, M.; Setälä, M.; Jäske, M.; Himmelroos, S. For the Sake of the Future: Can Democratic Deliberation Help Thinking and Caring about Future Generations? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafont, C. Deliberation, Participation, and Democratic Legitimacy: Should Deliberative Mini-Publics Shape Public Policy? J. Polit. Philos. 2014, 23, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Wilson, R. Local government and democratic innovations: Reflections on the case of citizen assemblies on climate change. Public Money Manag. 2022, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M. The MIT Collaboratorium: Enabling Effective Large-Scale Deliberation for Complex Problems. SSRN Electron. J. 2007, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toots, M. Why E-Participation Systems Fail: The Case of Estonia’s Osale.ee. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouter, N.; Koster, P.; Dekker, T. Participatory Value Evaluation for the Evaluation of Flood Protection Schemes. Water Resour. Econ. 2021, 36, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateman, C. Participatory Democracy Revisited. Perspect. Politics 2012, 10, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvad, A.M.; Popp-Madsen, B.A. Sortition-Infused Democracy: Empowering Citizens in the Age of Climate Emergency. Thesis Elev. 2021, 167, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Demski, C.; Cherry, C.; Verfuerth, C.; Steentjes, K. Climate Change Citizens’ Assemblies. In CAST Briefing Paper 03; The Centre For Climate Change And Social Transformation, Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brenninkmeijer, A.; Bouma, J.; Cuppen, E.; Van Damme, F.; Hendriks, F.; Lammers, K.; Shouten, W.; Tonkens, E.; Wielenga, W. Adviesrapport Betrokken bij Klimaat. 2021. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/publicaties/2021/03/21/adviesrapport-betrokken-bij-klimaat (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Goodin, R.E.; Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics. Politics Soc. 2006, 34, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R.; Curato, N.; Smith, G. Deliberative Democracy and the Climate Crisis. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2022, 13, e759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastil, J.; Levine, P. The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Board of Technology. World Wide Views on Global Warming: From the World’s Citizens to the Climate Policy-Makers; Policy Report; The Danish Board of Technology: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, C.M. The Democratic Soup: Mixed Meanings of Political Representation in Governance Networks. Governance 2009, 22, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.; Mansbridge, J.J. Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Setälä, M. Connecting Deliberative Mini-Publics to Representative Decision Making. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2017, 56, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, M. Advisory, Collaborative and Scrutinizing Roles of Deliberative Mini-Publics. Front. Polit. Sci. 2021, 2, 567297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courant, D. Des Mini-Publics Délibératifs Pour Sauver Le Climat? Arch. Philos. Droit 2020, 62, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C. When Citizen Deliberation Enters Real Politics: How Politicians and Stakeholders Envision the Place of a Deliberative Mini-Public in Political Decision-Making. Policy Sci. 2019, 52, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Niemeyer, S. Discursive Representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2008, 102, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandover, R.; Moseley, A.; Devine-Wright, P. Contrasting Views of Citizens’ Assemblies: Stakeholder Perceptions of Public Deliberation on Climate Change. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, C.; Herriman, J. Global Deliberative Democracy and Climate Change: Insights from World Wide Views on Global Warming in Australia. PORTAL J. Multidiscip. Int. Stud. 2011, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaquet, V. Explaining Non-Participation in Deliberative Mini-Publics. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2017, 56, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.; Newhart, M.; Vernon, R. Not by Technology Alone: The “Analog” Aspects of Online Public Engagement in Policymaking. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, G. Public Deliberation with Climate Change: Opening up or Closing down Policy Options? Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2015, 24, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradova, L.; Walker, H.; Colli, F. Climate Change Communication and Public Engagement in Interpersonal Deliberative Settings: Evidence from the Irish Citizens’ Assembly. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oross, D.; Mátyás, E.; Gherghina, S. Sustainability and Politics: Explaining the Emergence of the 2020 Budapest Climate Assembly. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiter, J.; Muradova, L.; Gastil, J.; Farrell, D.M. Scaling up Deliberation: Testing the Potential of Mini-Publics to Enhance the Deliberative Capacity of Citizens. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 2020, 26, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäske, M. Participatory Innovations and Maxi-Publics: The Influence of Participation Possibilities on Perceived Legitimacy at the Local Level in Finland. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2018, 58, 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblo, M.A.; Esterling, K.M.; Kennedy, R.P.; Lazer, D.M.; Sokhey, A.E. Who Wants to Deliberate—And Why? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2010, 104, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, L.; Torney, D.; Brereton, P.; Coleman, M. Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change: Lessons for Deliberative Public Engagement and Communication. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstub, S.; Farrell, D.M.; Carrick, J.; Mockler, P. Evaluation of Climate Assembly UK, Newcastle University 2021. Available online: https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/get-involved2/climate-assembly-uk/evaluation-of-climate-assembly-uk.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Courant, D. The Promises and Disappointments of the French Citizens’ Convention for Climate. Deliberative Democracy Digest, 2021. Available online: https://www.publicdeliberation.net/the-promises-and-disappointments-of-the-french-citizens-convention-for-climate/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- De Perthuis, C. Débat: La Convention Citoyenne Pour le Climat, et Après? The Conversation. 6 July 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/debat-la-convention-citoyenne-pour-le-climat-et-apres-141891 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Mouter, N.; Koster, P.; Dekker, T. Contrasting the Recommendations of Participatory Value Evaluation and Cost-Benefit Analysis in the Context of Urban Mobility Investments. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 144, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouter, N.; Shortall, R.M.; Spruit, S.L.; Itten, A.V. Including Young People, Cutting Time and Producing Useful Outcomes: Participatory Value Evaluation as a New Practice of Public Participation in the Dutch Energy Transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, S. The Emancipatory Effect of Deliberation: Empirical Lessons from Mini-Publics. Politics Soc. 2011, 39, 103–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastil, J.; Richards, R. Making Direct Democracy Deliberative through Random Assemblies. Politics Soc. 2013, 41, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Reflections on deliberative democracy. Contemp. Debates Polit. Philos. 2009, 17, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Lafont, C. Democracy without Shortcuts: A Participatory Conception of Deliberative Democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Lo, A.Y. Reason and Rhetoric in Climate Communication. Environ. Politics 2014, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K.; Decker, T.; Menrad, K. Public Participation in Wind Energy Projects Located in Germany: Which Form of Participation Is the Key to Acceptance? Renew. Energy 2017, 112, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, K.R.; Gastil, J.; Reedy, J.; Cramer Walsh, K. Did They Deliberate? Applying an Evaluative Model of Democratic Deliberation to the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2013, 41, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishkin, J.S. Democracy When the People Are Thinking: Revitalizing Our Politics through Public Deliberation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, R.E. Democratic Deliberation Within. Philos. Public Aff. 2000, 29, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczek, N.; Hecker, S.; Voigt-Heucke, S.L. The Known Unknowns: What Citizen Science Projects in Germany Know about Their Volunteers—And What They Don’t Know. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedock, C.; Pilet, J.-B. Who Supports Citizens Selected by Lot to Be the Main Policymakers? A Study of French Citizens. Gov. Oppos. 2020, 56, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, S.L.; Mouter, N.; Kaptein, L.; Ytsma, P.; Gommans, W.; Collewet, M.; Van Schie, N.; Karmat, A.; Knip, M. 1376 inwoners van Súdwest-Fryslân over het Toekomstige Energiebeleid van hun Gemeente: De uitkomsten van een Raadpleging. 2020. Available online: https://www.tudelft.nl/tbm/pwe/case-studies (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Wells, R. Citizens’ Assemblies and Juries on Climate Change: Lessons from Their Use in Practice. In Addressing the Climate Crisis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, S.; Bächtiger, A. Catching the deliberative wave? How (disaffected) citizens assess deliberative citizens forums. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.; Thompson, N.K.; Marston, G. Public Deliberation and Policy Design. Pol. Des. Pract. 2021, 4, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pow, J. Mini-Publics and the Wider Public: The Perceived Legitimacy of Randomly Selecting Citizen Representatives. Representation 2021, 57, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, E.; Warren, M.E. What Can Deliberative Mini-Publics Contribute to Democratic Systems? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2018, 58, 893–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Step | Stakeholder Type (Number) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| February 2020 | 1. Setting preconditions for the PVE consultation | Municipality Súdwest-Fryslân Council advisory committee | Preconditions for policy options to consider in step 2: hackathon |

| March 2020 | 2. First mini-public hackathon: drafting policy options | Citizens (45); Experts (7); Supervisors (7) | Six policy options and open questions for online PVE consultation |

| Between April and May 2020 | 3. Maxi-public: Online PVE consultation | Citizens (1356) | Citizens’ opinions about future energy policies of Súdwest-Fryslân |

| Between May and June 2020 | 4. Second mini-public: Citizens forum | Citizens (12) | Advise about future energy policies of Súdwest-Fryslân, based on results of PVE consultation |

| September 2020 | 5. Discussion and vote on the citizens forum’s advice | Municipal council of Súdwest-Fryslân (34 members) | Adoption of citizens guidelines in light of the Regional Energy Strategy |

| Education Maxi-Public | Education in the Municipality |

|---|---|

| 62% are highly educated | 26% are highly educated |

| 31% are medium-high educated | 43% are medium-high educated |

| 5% are low educated | 30% are low educated |

| Age maxi-public | Age in the municipality |

| 4% are between the age of 14 and 25 | 11.6% are between the age of 14 and 25 |

| 18% are between the age of 26 and 45 | 20.6% are between the age of 26 and 45 |

| 48% are between the age of 46 and 65 | 29.4% are between the age of 46 and 65 |

| 29% are between the age of 65 and older | 22.1% are between the age of 65 and older |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Itten, A.; Mouter, N. When Digital Mass Participation Meets Citizen Deliberation: Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Climate Policy-Making. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084656

Itten A, Mouter N. When Digital Mass Participation Meets Citizen Deliberation: Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Climate Policy-Making. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084656

Chicago/Turabian StyleItten, Anatol, and Niek Mouter. 2022. "When Digital Mass Participation Meets Citizen Deliberation: Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Climate Policy-Making" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084656

APA StyleItten, A., & Mouter, N. (2022). When Digital Mass Participation Meets Citizen Deliberation: Combining Mini- and Maxi-Publics in Climate Policy-Making. Sustainability, 14(8), 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084656