Toward the Sustainable Development of the Old Community: Proposing a Conceptual Framework Based on Meaning Change for Space Redesign of Old Communities and Conducting Design Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The International Debate on Urban Design

2.2. Sustainable Urban Design

3. Theory and Methods

3.1. The Concept of Meaning Change

3.2. The Role of Meaning Change in the Space Redesign of the Old Community

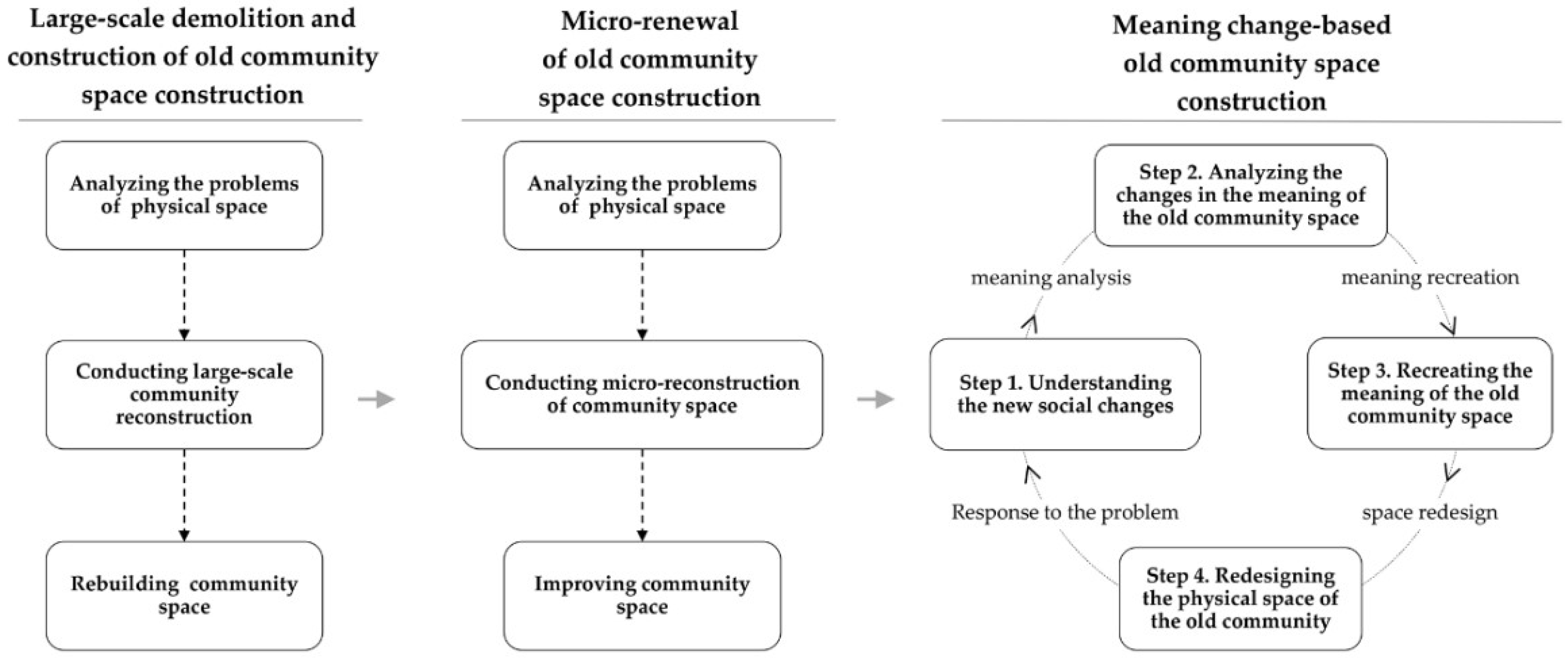

3.3. A Conceptual Framework for Space Redesign of the Old Community Based on Meaning Change

4. Results

4.1. Changes in the Meaning of Space in Old Communities

4.1.1. The Change of the Meaning of Space Due to Economic Development

4.1.2. The Change of the Meaning of Space Due to Population Migration and the Passage of Time

4.1.3. The Change of the Meaning of Space Due to Population Age Structure Change

4.2. A Case Study on Space’s Meaning Reconstruction and Design Practice of Old Community Based on the Conceptual Framework of Meaning Change

4.2.1. Case Selection

4.2.2. Analysis of Selected Case

4.2.3. Space’s Meaning Reconstruction and Design Practice of the Old Community of Rong Xiang in Wuxi Based on the Framework

- “Living Field” for daily activities

- 2.

- “Memory Field” of the place spirit

- 3.

- “Full Aged Field” for the generational balance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, N.; Li, Y. Review of International Urban Renewal Movement. World Econ. Polit. Forum 1999, 17, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Q. Community Service in the demolition of Shuangtang Street in Nanjing. China Civ. Aff. 1995, 2, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Luo, J. Promote urban transformation by demolition and relocation. Econ. Forum 1999, 6, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kunming Housing Demolition Management Office. Remarkable achievements in the demolition work in Kunming. China Real Estate 1999, 6, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhu, L. Innovation and Exploration of Urban Community Renewal—Taking the EnEff: City as an example. Resid. Technol. 2018, 38, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Gearing Type Urban Regeneration Strategy: Case on Otemachi Development in Tokyo, Japan. Urban Plan. Int. 2018, 33, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Yang, R. Threads and Clues: Spatio-Temporal Evolution Paths and Characteristics of Micro Regeneration Practices in Chongqing. Archit. J. 2020, 67, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J.; Zhang, Y. Research on Evaluation of Urban Organic Renewal Policy Effect and Optimization Strategy—Take “Three Reconstructions and One Demolition” in Hangzhou for Example. Reform Econ. Syst. 2020, 38, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Wang, Z. Urban Public Space Renewal driven by Cultural Planning—A Case Study of the Cultural Corridor on the West Bank of Pujiang River in Shanghai. Art Panor. 2020, 27, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Annex A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://www.un.org/zh/documents/treaty/files/A-RES-70-1.shtml (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Spreiregen, P.D. Urban Design: The Architecture of Towns and Cities; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gibberd, F. Town Design; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Townscape; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, R.S. Zoning for Downtown Urban Design: How Cities Control Development; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, I. Responsive Environments: A Manual for Designers; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A New Theory of Urban Design; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Planning Association; Steiner, F.R.; Butler, K. Planning and Urban Design Standards; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, D. Städtebau zwischen Architektur und Stadtplanung: Zum Verhältnis von Städtebau-, Architektur- und Planungstheorie. disP Plan. Rev. 2009, 45, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, M.C. A spectrum of urban design roles. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belof, M.; Kryczka, P. Between Architecture and Planning: Urban Design Education in Poland against a Background of Contemporary World Trends. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2021, 0739456X211057205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, A. Definitions of urban design: The nature and concerns of urban design. Plan. Pract. Res. 1994, 9, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, D. Urban design for sustainability: A study on the Turkish city. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2004, 11, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Sustainable urban design: Principles to practice. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 12, 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M.; Adriaens, F.; van der Linden, O.; Schik, W. A next step for sustainable urban design in the Netherlands. Cities 2011, 28, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjafar, M.R.; Pourjafar, A. Sustainable urban design; past, present, and future Case study: Darabad River Valley. Sci. Iran. 2016, 23, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medved, P.; Kim, J.I.; Ursic, M. The urban social sustainability paradigm in Northeast Asia and Europe A comparative study of sustainable urban areas from South Korea, China, Germany and Sweden. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchol-Salort, P.; O’Keeffe, J.; van Reeuwijk, M.; Mijic, A. An urban planning sustainability framework: Systems approach to blue green urban design. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlakha, D.; Chandra, M.; Krishna, M.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.A. Designing Age-Friendly Communities: Exploring Qualitative Perspectives on Urban Green Spaces and Ageing in Two Indian Megacities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, L.M.; Laursen, L.N. Meaning Frames: The Structure of Problem Frames and Solution Frames. Des. Issues 2019, 35, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Maslow’s Humanism Philosophy; Jiuzhou Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lü, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Dong, W.; Liu, P.; Huang, Z.; Wu, B.; Lu, S.; Xu, F.; et al. Memory and homesickness in transition: Evolution mechanism and spatial logic of urban and rural memory. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology; Central Compilation & Translation Press, CCTP: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Architectural Experience—The Plot in Space; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci, Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Huazhong University of Science & Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Save the place of memory and construct Cultural identity. People’s Daily, 12 April 2012; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadikhah, H.; Ziari, K. Social sustainability between old and new neighborhoods (case study: Tehran neighborhoods). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 2596–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhoerster, H.; Weck, S. Cross-local ties to migrant neighborhoods: The resource transfers of out-migrating Turkisn middle-class households. Cities 2016, 59, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbaugh, E. Designing communities to enhance the safety and mobility of older adults—A universal approach. J. Plan. Lit. 2008, 23, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.; Jespersen, A.P.; Troelsen, J. Going along with older people: Exploring age-friendly neighbourhood design through their lens. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, Z.; Guo, W.; Liu, J.; Xu, S. Toward the Sustainable Development of the Old Community: Proposing a Conceptual Framework Based on Meaning Change for Space Redesign of Old Communities and Conducting Design Practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084755

Xing Z, Guo W, Liu J, Xu S. Toward the Sustainable Development of the Old Community: Proposing a Conceptual Framework Based on Meaning Change for Space Redesign of Old Communities and Conducting Design Practices. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084755

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Zhaolian, Weimin Guo, Jia Liu, and Shu Xu. 2022. "Toward the Sustainable Development of the Old Community: Proposing a Conceptual Framework Based on Meaning Change for Space Redesign of Old Communities and Conducting Design Practices" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084755