Competencies of Sustainability Professionals: An Empirical Study on Key Competencies for Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

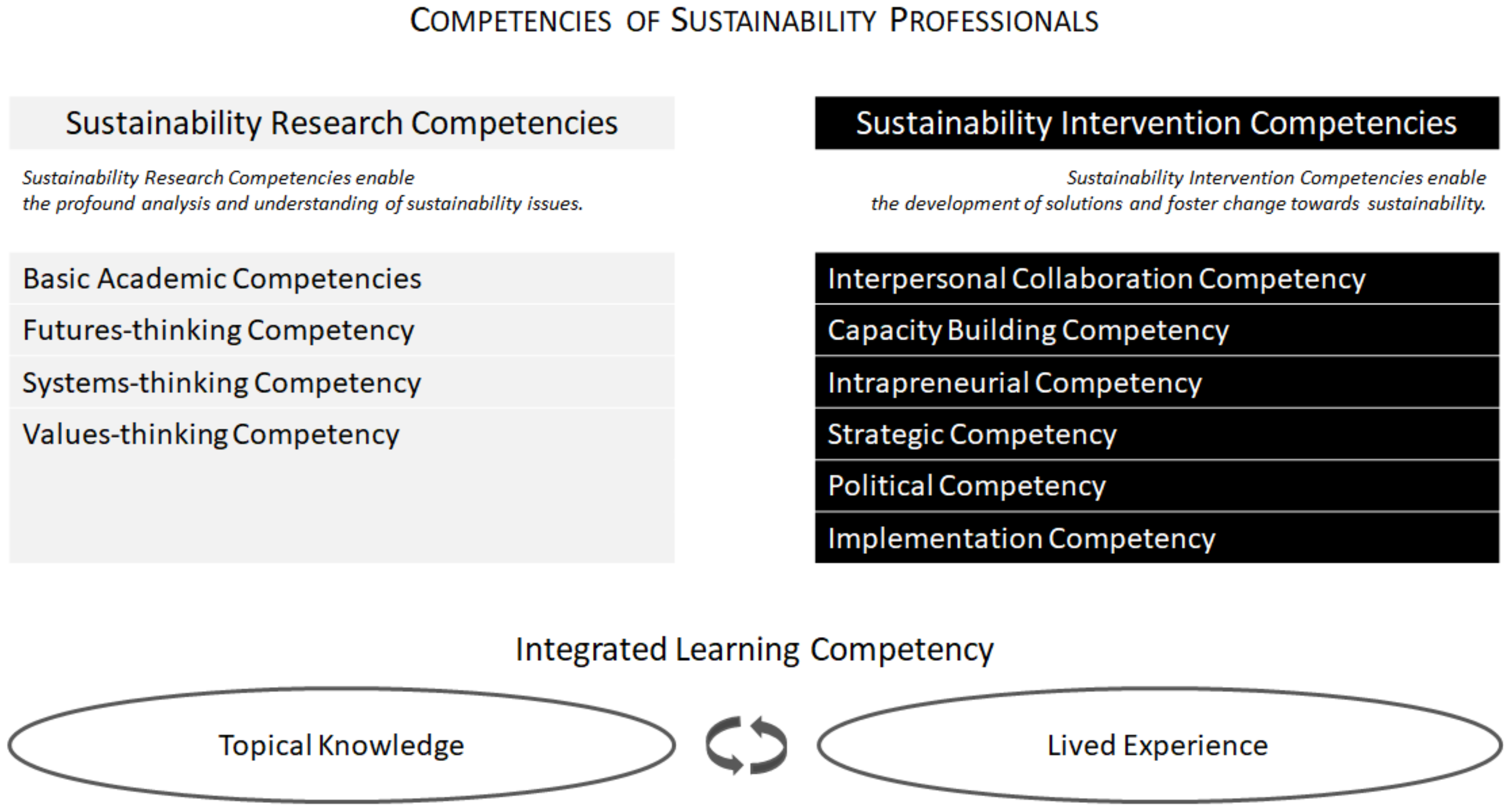

2. Competencies for Sustainability

3. Methodology

3.1. First Stage—Identification and Selection of Action Research Participants

3.2. Second Stage—Interactive Workshop

3.3. Third Stage—Semi-Structured Interviews

3.4. Fourth Stage—Online Survey

4. Results

4.1. Sustainability Intervention Competencies

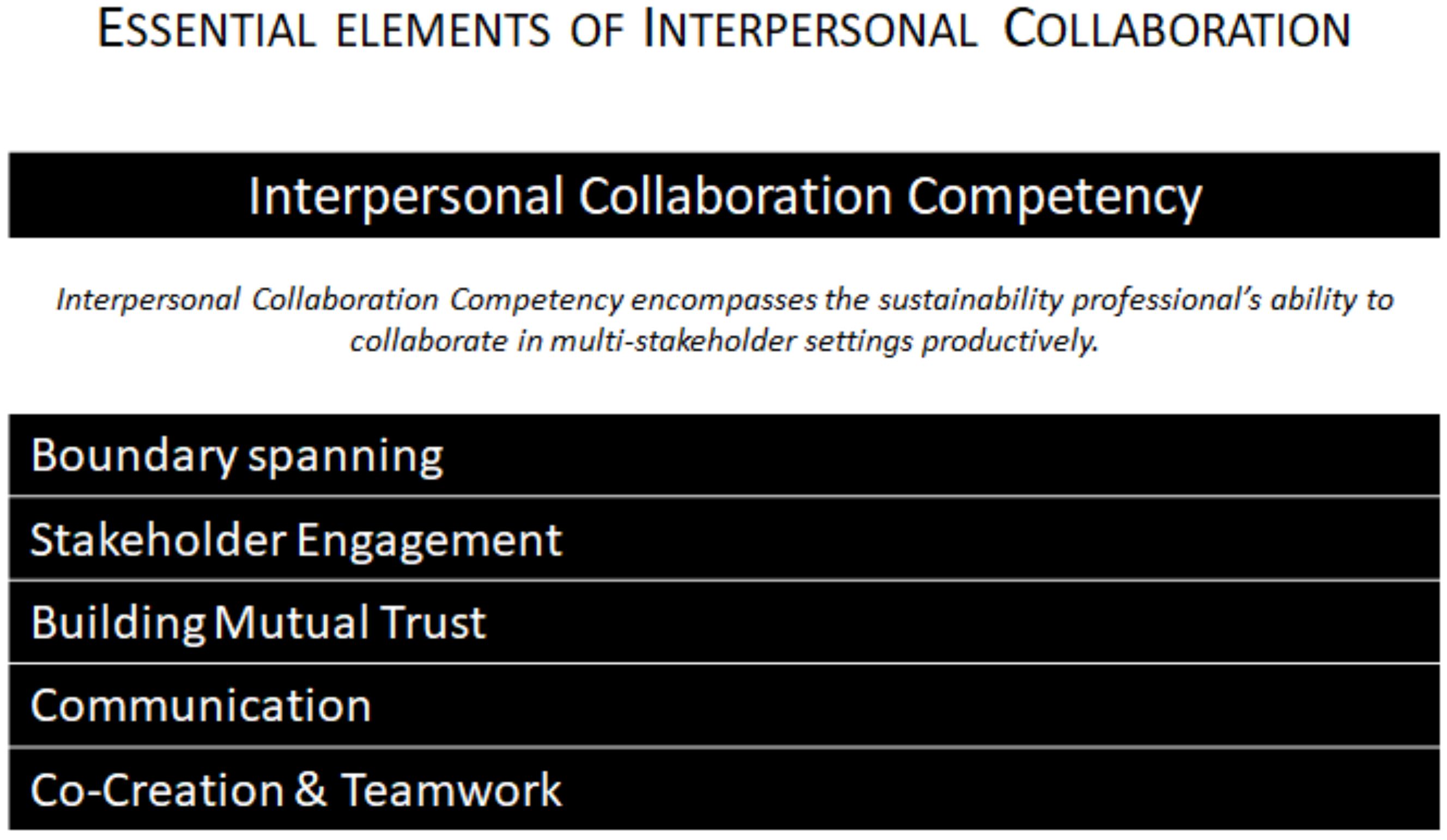

4.1.1. Interpersonal Collaboration Competency

4.1.2. Capacity Building Competency

4.1.3. Intrapreneurial Competency

4.1.4. Strategic Competency

4.1.5. Political Competency

4.1.6. Implementation Competency

4.2. Sustainability Research Competencies

4.2.1. Basic Academic Competencies

4.2.2. Systems-Thinking

4.2.3. Futures-Thinking

4.2.4. Values-Thinking

4.3. Knowledge and Learning

4.3.1. Lived Experience

4.3.2. Topical Knowledge

4.3.3. Integrated Learning Competency

5. Discussion of Findings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Length Interview | Background Description Interviewees | Work Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview 1 | 33:56 min. | Director anthroposophical educational institution, teacher biology and sustainability | 40 years |

| Interview 2 | Continued in writing due to technical issues | Sustainability official (public institution), Editor-in-chief of a non-scientific sustainability journal, executive board member of an international NGO for environmental education, author | 32 years |

| Interview 3 | 1:07:00 min. | Director sustainable food academy, chef, speaker, author | 21 years |

| Interview 4 | 49:35 min. | Lecturer in sustainability philosophy, trainer for teachers in biology and sustainability, author | 16 years |

| Interview 5 | 29:48 min. | Director vocational educational institution (sustainable agriculture), consultant and coach | 30 years |

References

- WCED. Our Common Future—Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S. Building successful social partnerships. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1988, 29, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Willard, M.; Wiedmeyer, C.; Flint, R.W.; Weedon, J.S.; Woodward, R.; Feldman, I.; Edwards, M. The sustainability professional: 2010 competency survey report. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2010, 20, 49–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000, 7, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, F.P.; Abbott, D.; Wilson, G. Dimensions of professional competences for interventions towards sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salovaara, J.J.; Soini, K. Educated professionals of sustainability and the dimensions of practices. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbarth, C.; Schaltegger, S. Educating change agents for sustainability—Learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Ordonez-Ponce, E.; Chai, Z.; Andreasen, J. Sustainability managers: The job roles and competencies of building sustainable cities and communities. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2020, 43, 1413–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrivou, K.; Bradbury-Huang, H. Educating integrated catalysts: Transforming business schools Toward ethics and sustainability. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Klink, M.; Boon, J. The investigation of competencies within professional domains. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2002, 5, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baartman, L.K.J.; Bastiaens, T.J.; Kirschner, P.A.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Evaluating assessment quality in competence-based education: A qualitative comparison of two frameworks. Educ. Res. Rev. 2007, 2, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Haan, G. The BLK ‘21′ programme in Germany: A ‘Gestaltungskompetenz’-based model for education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development; Draft Resolution A/C.2/57/L.45; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Roadmap UNESCO for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen, G.; Wells, P.J. A Decade of Progress on Education for Sustainable Development Reflections from the UNESCO Chairs Programme; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development—A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Learning for the Future: Competences in Education for Sustainable Development; UNECE: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I.; Day, T. Sustainability capabilities, graduate capabilities, and Australian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risopoulos-Pichler, F.; Daghofer, F.; Steiner, G. Competences for solving complex problems: A cross-sectional survey on higher education for sustainability learning and transdisciplinarity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoof, A.; Martens, R.L.; Van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Bastiaens, T.J. The boundary approach of competence: A constructivist aid for understanding and using the concept of competence. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2002, 1, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, F.P.; Wilson, G.; van der Klink, M. Transforming academic knowledge and the concept of lived experience: Intervention competence in an international e-learning programme. E-Learn. Educ. Sustain. 2015, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A. Structuring and advancing solution-oriented research for sustainability. Ambio 2021, 51, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, H.; Waddell, S.; Brien, K.O.; Apgar, M.; Teehankee, B.; Fazey, I. A call to action research for transformations: The times demand it. Action Res. 2019, 17, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable development: A bird’s eye view. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mabon, L.; Shih, W.-Y. Urban greenspace as a climate change adaptation strategy for subtropical Asian cities: A comparative study across cities in three countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 68, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, L.; Shriberg, M. Sustainability leadership programs in higher education: Alumni outcomes and impacts. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, G. The development of ESD-related competencies in supportive institutional frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 2010, 56, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Marcote, P.; Varela-Losada, M.; Álvarez-Suárez, P. Evaluation of an educational model based on the development of sustainable competencies in basic teacher training in Spain. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2603–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavicchi, C. Higher education and the sustainable knowledge society: Investigating Students’ perceptions of the acquisition of sustainable development competences Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, T.; Wiek, A.; Barth, M. Learning processes for interpersonal competence development in project-based sustainability courses—insights from a comparative international study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 535–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Heras, R.; Mulà, I.; Salgado, F.P.; Henderson, L. Competences to address SDGs in higher education-a reflection on the equilibrium between systemic and personal approaches to achieve transformative action. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambrechts, W.; van Petegem, P. The interrelations between competences for sustainable development and research competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, H.L.; Gabriel, L.C.; Sahakian, M.; Cattacin, S. Practice-based program evaluation in higher education for sustainability: A student participatory approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Michelsen, G.; Rieckmann, M.; Thomas, I. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hanson, W.E.; Clark, V.L.P.; Morales, A. Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues 1946, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kemmis, S. What is to be done? The place of action research. Educ. Action Res. 2010, 18, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, J. Action Research: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. (Eds.) Introduction. In Handbook of Action Research—Concise Paperback Edition; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. (Eds.) Introduction. In The Sage Handbook of Action Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. Action learning and action research: Paradigm, praxis and programs. In Action Research; Sankaran, S., Dick, B., Passfield, R., Eds.; Southern Cross University Press: Lismore, Australia, 2001; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, C.; Huxham, C. Action research for management research. Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrichter, H.; Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Zuber-Skerritt, O. The concept of action research. Learn. Organ. 2002, 9, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Holwell, S. Action research: Its nature and validity. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 1998, 11, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melrose, M.J. Maximizing the rigor of action research: Why would you want to? How could you? Field Methods 2001, 13, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennie, J. Increasing the rigour and trustworthiness of participatory evaluations: Learnings from the field. Eval. J. Australas. 2006, 6, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dick, B. What can grounded theorists and action researchers learn from each other. In The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007; pp. 398–416. [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran, S.; Dick, B. Linking theory and practice in using action-oriented methods. In Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M. Academic integrity in action research. Action Res. 2012, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenberger, C.; Good, J.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Iversen, O.S. In pursuit of rigour and accountability in participatory design. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.B. What is good action research? Why the resurgent interest? Action Res. 2010, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Venn, R.; Berg, N. The gate-keeping function of trust in cross-sector social partnerships. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2014, 119, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuteleers, S.; Hugé, J. Value pluralism in ecosystem services assessments: Closing the gap between academia and conservation practitioners. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 2016–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD. Vision 2050; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD; UNEP. Translating ESG into Sustainable Business Value; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halme, M.; Lindeman, S.; Linna, P. Innovation for inclusive business: Intrapreneurial bricolage in multinational corporations. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 743–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, R.; Berg, N. Building competitive advantage through Social Intrapreneurship. South Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, D.; Wilson, G. The lived experience of climate change: Complementing the natural and social sciences for knowledge, policy and action. Int. J. Clim. Change-Impacts Responses 2012, 3, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, D.; Wilson, G. Climate change: Lived experience, policy and public action. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2014, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konrad, T.; Wiek, A.; Barth, M. Embracing conflicts for interpersonal competence development in project-based sustainability courses. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kraker, J.; Lansu, A.; Van Dam-Mieras, R. Competences and competence-based learning for sustainable development. In Crossing Boundaries: Innovative Learning for Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Verlag für Akademisch Schriften: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2007; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lansu, A.; Boon, J.; Sloep, P.B.; van Dam-Mieras, R. Changing professional demands in sustainable regional development: A curriculum design process to meet transboundary competence. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barroso-Méndez, M.J.; Galera-Casquet, C.; Seitanidi, M.M.; Valero-Amaro, V. Cross-sector social partnership success: A process perspective on the role of relational factors. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 40, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neessen, P.C.M.; Caniëls, M.C.J.; Vos, B.; de Jong, J.P. The intrapreneurial employee: Toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Runhaar, H.; Driessen, P.; Vermeulen, W. Policy competences of environmental sustainability professionals. Greener Manag. Int. 2005, 49, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Thibault, L. Challenges in multiple cross-sector partnerships. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2009, 38, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidi, M.M. The Politics of Partnerships; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy 1973, 2, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. A Cognitive Theory of the Firm; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom, B. Learning by interaction: Absorptive capacity, cognitive distance and governance. J. Manag. Gov. 2000, 4, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, G.; Xia-Bauer, C.; Roelfes, M.; Schüle, R.; Vallentin, D.; Martens, L. Competences of local and regional urban governance actors to support low-carbon transitions: Development of a framework and its application to a case-study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molderez, I.; Fonseca, E. The efficacy of real-world experiences and service learning for fostering competences for sustainable development in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4397–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A.; Barth, M. Current practice of assessing students’ sustainability competencies: A review of tools. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. Research notes and commentaries: What passes as rigorous case study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 1474, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Fadeeva, Z. Competences for sustainable development and sustainability: Significance and challenges for ESD. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Male | 5 (20%) 20 (80%) |

| Education | None High School/Secondary School Bachelor Master PhD | 1 (4%) 7 (28%) 8 (32%) 8 (32%) 1 (4%) |

| Work Experience as Sustainability Professional | 6–10 years 10–20 years 20–30 years 30+ years | 3 (12%) 6 (24%) 8 (32%) 8 (32%) |

| Average | 24 years of work experience as sustainability professional | |

| Affiliation | Local municipality Educational institution Nature conservation center State authority NGO or temporary Campaign | 5 (20%) 5 (20%) 6 (24%) 5 (20%) 4 (16%) |

| Selective Coding (Competency Cluster) | Axial Coding (Key Competency) | Raw Data Examples (Translated from Original Dutch Data) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Intervention Competencies | Interpersonal Collaboration Competency | >Boundary spanning | Resolve conflicts; Identify and resolve conflicts of interests; Compromise; Identify and meet needs of others; Have empathy; Take time and listen; Interact one on one; Mediate; Look for common ground; Create win-win. |

| >Stakeholder Engagement | Integration of external stakeholders is crucial; Be locally embedded; Know your stakeholders; Integrate in social networks; Build social capital; Bring stakeholders together; Begin locally and work bottom-up. | ||

| >Co-Creation | Co-creation is very important; Co-creation creates shared responsibility; Teamwork & Co-creation; It is important to work in teams; Produce practical outcomes; Co-creation is crucial; Not getting everyone on board leads to failure of the project. | ||

| >Communication | Communicate with all stakeholders; Broad communication necessary; Clear communication; Translate complex issues; Take notes and write reports; Use the power of press and social media; Use symbols; Advertise. | ||

| >Building Mutual Trust | Plan intervention by someone they trust and who dares to tell the truth; Be trustable and don’t push choices; Be a trustable person when you ask for change; You need trustable scientific knowledge; You cannot work without trust in both directions. | ||

| Capacity Building Competency | Advise stakeholders and build up their knowledge base, Share scientific knowledge with stakeholders; Motivate others; Building intrinsic motivation is important; Be a role model; Takes responsibility and be an example; Make others enthusiast; Stimulate ownership; Strive for shared responsibility; Let others take over; Build a group that feels ownership and shares responsibility; Inspire others. | ||

| Intrapreneurial Competency | Identify needs and be entrepreneurial; Feel ownership; Be personally involved; Be owner of the project; Take the initiative; Be passionate about nature and spread the word; Go for quick-wins; Look for opportunities; Achieve results; Break it down into small achievable goals; Take small actions so that you quickly achieve results; Work locally and look for feasible actions; Feasibility and straightforwardness. | ||

| Strategic Competency | Set objectives, Set priorities; Objectives need to be clear; Take decisions; Stimulate the group to take decisions; Delegate; Dare to think big; Let go of what costs too much energy; Change your strategy where necessary; Act strategic; Think strategic; Timing must be right; It must happen at the right time and in the right place; Be persistent: You rarely achieve goals directly. Sometimes it take 10 to 20 years. | ||

| Political Competency | Politics are influenced by powerful corporations (lobby); Anticipate lobbying by corporations; Never underestimate the industry lobby; Take political agendas into account; Power is necessary; Be aware that politicians want to get votes and be re-elected; Consider which interests might prevail; Be political neutral; Don’t have a hidden agenda; Be open for discussion and debate; Political-thinking is important. | ||

| Implementation Competency | Thinking and acting has to go together; Take action; Push through; Follow up; Implement; Gain support in your organization; Gain support by the general public; Support of stakeholders is crucial; Look for like-minded people to get it done; Look for sponsors with self-interest; Manage the project and the process; Establish continuity and follow-ups; Self-directed succession is important. |

| Selective Coding (Competency Cluster) | Axial Coding (Key Competency) | Raw Data Examples (Translated from Original Dutch Data) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Research Competencies | Basic academic competencies | >Critical-thinking | Dare to take a look as an outsider to reveal absurdities; Have a broad perspective and be critical. |

| >Analytical- thinking | Think analytically and systematically; Analyze the situation. | ||

| >Research & Data Management | Apply analytical techniques; Measure and analyze the ecosystem. | ||

| Future-thinking competency | Anticipation is important; Dare to think long term; See through things and anticipate; You need an understanding of possible consequences; The value of biodiversity then, now, and where do we want to go? | ||

| System-thinking competency | Reduce complexity to something recognizable; Use system-thinking; You have to map ecology and the social aspects. | ||

| Value-thinking competency | Collaboration has to be based on equality; Search for people with ideals and not the ideal people; Take decisions in balance with your conscience and values; Take responsibility and choose freedom above obedience. |

| Selective Coding (Competency Cluster) | Axial Coding (Knowledge Category) | Raw Data Examples (Translated from Original Dutch Data) |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Learning Competency | Topical knowledge | You need a sound understanding of ecological and social aspects; Get into the matter; Get facts/scientific studies; Know the structures; We know a lot about ecology, the environment, sustainability, and the ultimate goal of saving biodiversity; Know and apply impact measurement; Measure the impact of your campaign. |

| Lived experience | Don’t try to re-invent the wheel; Know best practices; Importance of getting insights from the past; What are the best practices from the past?; What has already happened?; Find out what went well in previous projects and what works elsewhere. What should we keep? What can we improve?; How do they do it elsewhere; hat works? What not?; Be aware that this is not the first hype-we had this in the 70’s and 90’s as well; Be open to external expertise; We have to expand our competences and immerse into other topics. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venn, R.; Perez, P.; Vandenbussche, V. Competencies of Sustainability Professionals: An Empirical Study on Key Competencies for Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094916

Venn R, Perez P, Vandenbussche V. Competencies of Sustainability Professionals: An Empirical Study on Key Competencies for Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094916

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenn, Ronald, Paquita Perez, and Valerie Vandenbussche. 2022. "Competencies of Sustainability Professionals: An Empirical Study on Key Competencies for Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094916