“If You Don’t Know Me by Now”—The Importance of Sustainability Initiative Awareness for Stakeholders of Professional Sports Organizations †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Distance

2.2. Sustainable Initiatives Topics in the Professional Sport Organization Questionnaire

2.2.1. Diversity and Inclusion

2.2.2. Attraction and Retention of Human Capital

3. Research Design

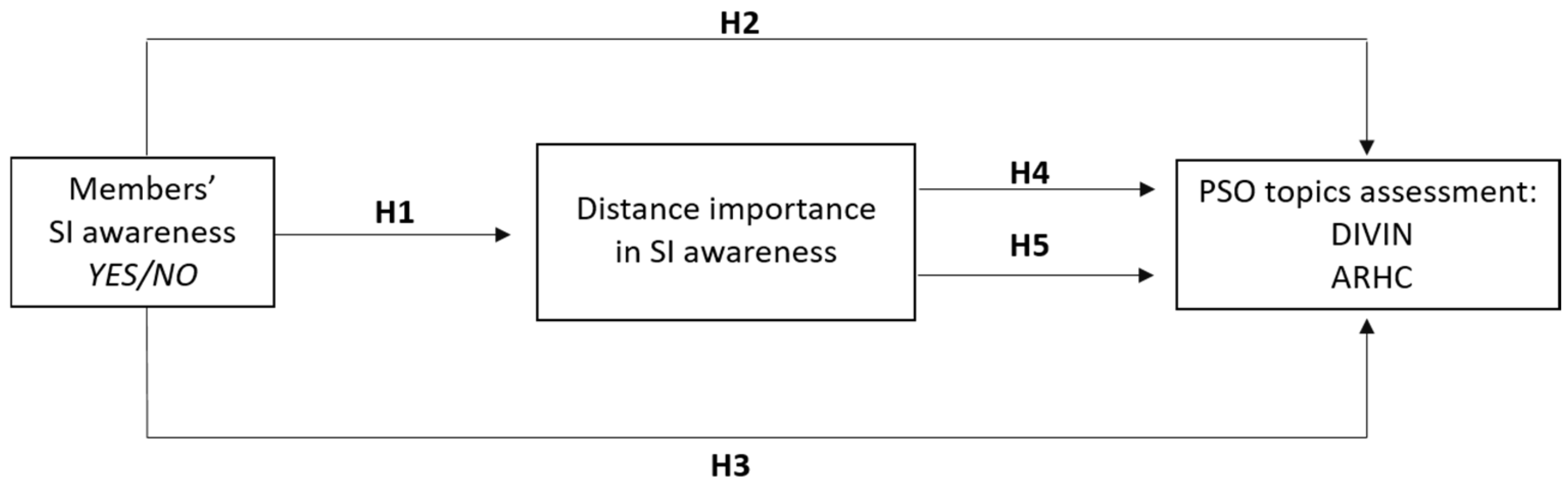

- RQ1. Are members aware of the SI programs implemented by the PSO?

- RQ2. What is the importance of distance on members’ SI awareness?

- RQ3. How do the PSO members evaluate the topics of DIVIN and ARHC?

- RQ4.What is the relationship between members’ SI awareness and the assessment of the topics of DIVIN and ARHC?

- RQ5. What is the relationship between distance and the members’ assessment of the topics of DIVIN and ARHC?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Context

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Treatment and Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Awareness

5.2. Distance

Topics

5.3. Topics Assessment

6. General Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Underwood, R.L.; Klein, N.M.; Burke, R.R. Packaging communication: Attentional effects of product imagery. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2001, 10, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaux, B. A stakeholder approach to football club governance. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2008, 4, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.J.; McDonald, H.; Funk, D.C. The uniqueness of sport: Testing against marketing’s empirical laws. Sport Man. Rev. 2016, 19, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Darvin, L. Mass-participant Sport Events and Sustainable Development: Gender, Social Bonding, and Connectedness to Nature as Predictors of Socially and Environmentally Responsible Behavior Intentions. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. 2015, p. 41. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Kellison, T.B. Sport Ecology: Conceptualizing an Emerging Subdiscipline Within Sport Management. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, G.T.; McCullough, B.P. Marketing sustainability through sport: Testing the sport sustainability campaign evaluation model. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 20, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, H.; Takeuchi, K. Sustainability Science: Building a New Discipline. Sustain. Sci. 2006, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Norris, J.; Brinkmann, R. Sustainability initiatives in professional soccer. Soccer Soc. 2017, 18, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; McCullough, B.P.; Pfahl, M.E. Examining environmental fan engagement initiatives through values and norms with intercollegiate sport fans. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Kent, A. Investigating the role of corporate credibility in corporate social marketing: A case study of environmental initiatives by professional sport organizations. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maditati, D.R.; Munim, Z.H.; Schramm, H.-J.; Kummer, S. A review of green supply chain management: From bibliometric analysis to a conceptual framework and future research directions. Res. Cons. Recycl. 2018, 139, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, G.T.; McCullough, B.P. Differential Effects of Internal and External Constraints on Sustainability Intentions: A Hierarchical Regression Analysis of Running Event Participants by Market Segment. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain. 2018, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E.; McCullough, B.P. Intercollegiate sport and the environment: Examining fan engagement based on athletics department sustainability efforts. J. Issues Intercoll. Athl. 2014, 7, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, J.M.; Bocarro, J.N.; Lothary, A.F. An examination of pickleball participation, social connections, and psychological well-being among seniors during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Leis. J. 2021, 63, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covell, D. Attachment, Allegiance and a Convergent Application of Stakeholder Theory: Assessing the Impact of Winning on Athletic Donations in the Ivy League. Sport Mark. Quart. 2005, 14, 168–176. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=18451704&site=ehost-live (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- García, B.; Welford, J. Supporters and football governance, from customers to stakeholders: A literature review and agenda for research. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; Babiak, K. Understanding strategic corporate environmental responsibility in professional sport. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2013, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Ries, R.J.; Kaplanidou, K. Carbon Dioxide Emissions of spectators’ transportation in collegiate sporting events: Comparing on-campus and off-campus stadium locations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosumu, A.; Colbeck, I.; Bragg, R. Greenhouse gas emissions as a result of spectators travelling to football in England. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chard, C.; Mallen, C. Examining the linkages between automobile use and carbon impacts of community-based ice hockey. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Flynn, A. Measuring the environmental sustainability of a major sporting event: A case study of the FA Cup Final. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolf, M.; Teehan, P. Reducing the carbon footprint of spectator and team travel at the University of British Columbia’s varsity sports events. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P. The carbon footprint of active sport participants. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M.; Schneider, I. Substitution interests among active-sport tourists: The case of a cross-country ski event. J. Sport Tour. 2018, 22, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Manual on Sport and the Environment. 2005. Available online: https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Olympism-in-Action/Environment/Manual-on-Sport-and-the-Environment.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Cayolla, R.; Santos, T.; Quintela, J.A. Sustainable Initiatives in Sports Organizations—Analysis of a Group of Stakeholders in Pandemic Times. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciletti, D.; Lanasa, J.; Ramos, D.; Luchs, R.; Lou, J. Sustainability Communication in North American Professional Sports Leagues: Insights from Web-Site Self-Presentations. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2010, 3, 64–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall-Tweedie, J.; Nguyen, S.N. Is the Grass Greener on the Other Side? A Review of the Asia-Pacific Sport Industry’s Environmental Sustainability Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Chard, C.; Sime, I. Web Communications of Environmental Sustainability Initiatives at Sport Facilities Hosting Major League Soccer. J. Manag. Sustain. 2013, 3, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blankenbuehler, M.; Kunz, M.B. Professional Sports Compete to Go Green. Am. J. Manag. 2014, 14, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, G.; McCullogh, B. A Longitudinal Study of Sustainability Attitudes, Intentions, and Behaviors. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Kent, A. Sport Teams as Promoters of Pro-Environmental Behavior: An Empirical Study. J. Sport Manang. 2012, 26, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapo. 1860 Titles. 2018. Available online: https://desporto.sapo.pt/futebol/primeira-liga/artigos/fc-porto-125-anos-e-1860-titulos-dragoes-correm-para-mais-um-campeonato (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- FCPorto. Many Faces. 2020. Available online: https://www.fcporto.pt/pt/noticias/20200117-pt-many-faces-estes-sao-os-artistas-que-vao-cantar-pela-igualdade (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Maisfutebol. The Same Ambition. 2021. Available online: https://maisfutebol.iol.pt/desporto-adaptado/wendell/a-mesma-ambicao-fc-porto-assinala-o-dia-da-pessoa-com-deficiencia (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Greensavers. A Estratégia de Sustentabilidade do Futebol Clube do Porto. 2013. Available online: https://greensavers.sapo.pt/a-estrategia-de-sustentabilidade-do-futebol-clube-do-porto (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Transfermarket. Número de Espetadores 21/22. 2021. Available online: https://www.transfermarkt.pt/liga-portugal-bwin/besucherzahlen/wettbewerb/PO1/saison_id/2021 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- The Stadium Guide. Europe’s Largest Football Stadiums. 2021. Available online: https://www.stadiumguide.com/figures-and-statistics/lists/europes-largest-football-stadiums/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- FC Porto. Colour Inclusion. 2021. Available online: https://www.fcporto.pt/pt/noticias/20210106-pt-fc-porto-aposta-na-inclusao-pela-cor-nas-suas-infraestruturas (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- FC Porto. Adapted Sport. 2021. Available online: https://www.fcporto.pt/pt/modalidades/desporto-adaptado/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- FC Porto. Adapted Sports Trophies are Already in the Museum. 2021. Available online: https://www.fcporto.pt/pt/noticias/20210713-pt-trofeus-mais-recentes-do-desporto-adaptado-ja-estao-no-museu (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- FC Porto. Museu FC Porto e Estádio do Dragão Recebem Prémio Travellers Choice. 2020. Available online: https://www.fcporto.pt/pt/noticias/20200821-pt-museu-fc-porto-e-estadio-do-dragao-recebem-premio-travellers-choice (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Tripadvisor. Museums in Porto. 2021. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.pt/Attractions-g189180-Activities-c49-Porto_Porto_District_Northern_Portugal.htm (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Nyaupane, G.; Graefe, A.R. Travel distance: A tool for nature-based tourism market segmentation. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Jogo. FC Porto Revela ter Atingido Quase 140 Mil Sócios. 2020. Available online: https://www.ojogo.pt/futebol/1a-liga/porto/noticias/fc-porto-revela-ter-atingido-quase-140-mil-socios--12727576.html (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Finance Futebol. Top. 10 Clubes com Mais Sócios. 2020. Available online: https://financefootball.com/2020/06/12/top-10-clubes-com-mais-socios/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Liga NOS. Ranking Redes Sociais—Liga NOS (12/2020). 2021. Available online: https://football-industry.com/ranking-redes-sociais-liga-nos-12-2020/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Guichard, F. Porto, la Ville Dans sa Région. Contribution à l’Etude de l’Organisation de l’Espace Dans le Portugal du Nord; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisbon, Portugal, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- FC Porto. Diáspora Portista: FC Porto tem Quase 140 Mil Sócios. 2020. Available online: https://www.fcporto.ws/diaspora-portista-fc-porto-tem-quase-140-mil-socios/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Rosati, F. Organisational tensions and the relationship to CSR in the football sector. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.M.; Yan, G.; Soebbing, B.P.; Fu, W. Air Pollution and Attendance in the Chinese Super League: Environmental Economics and the Demand for Sport. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Kellison, T.B. Go Green for the Home Team: Sense of Place and Environmental Sustainability in Sport. J. Sustain. Ed. 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kellison, T.B.; Kim, Y.K. Marketing Pro-Environmental Venues in Professional Sport: Planting Seeds of Change Among Existing and Prospective Consumers. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S. Sport Subcultures and Their Potential for Addressing Environmental Problems: The Illustrative Case of Disc Golf. Cyber J. Appl. Leis. Recreat. Res. 2011, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, B.P.; Pelcher, J.; Trendafilova, S. An Exploratory Analysis of the Environmental Sustainability Performance Signaling Communications among North American Sport Organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaia, R. Spectators’ Experiences at the Sport and Entertainment Facility: The Key for Increasing Attendance Over the Season. Sport Entert. Rev. 2015, 1, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peachey, J.W.; Zhou, Y.; Damon, Z.J.; Burton, L.J. Forty years of leadership research in sport management: A review, synthesis, and conceptual framework. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavic, P.; Lukman, R. Review of Sustainability Terms and Their Definitions. J. Cleaner Prod. 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Theoretical insights on integrated reporting: The inclusion of non-financial capitals in corporate disclosures. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic attributions of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: The business case for doing well by doing good! Sustain. Dev. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Members Awareness | Frequency (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| NO | 3708 | 65.1 |

| YES | 1986 | 34.9 |

| Total | 5694 | 100 |

| District | Frequency (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Porto | 4104 | 71.8 |

| Braga | 335 | 5.9 |

| Aveiro | 328 | 5.8 |

| Lisbon | 233 | 4.1 |

| All the others | 694 | 12.4 |

| Total | 5694 | 100 |

| Zone | Global Population (GP) | Quest (n) | GP/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 231.962 | 1098 | 0.47/19.3 |

| Zone 2 | 611.777 | 1776 | 0.29/31.2 |

| Zone 3 | 9,504,153 | 2502 | 0.02/43.9 |

| NULL | - | 318 | −/5.6 |

| Total | 10,347,892 | 5694 | 100 |

| SI Awareness | No SI Awareness | |

|---|---|---|

| Zone | n/% | n/% |

| Zone 1 | 336/16.9 | 762/20.5 |

| Zone 2 | 631/31.8 | 1145/31 |

| Zone 3 | 932/46.9 | 1570/42.3 |

| NULL | 87/4.4 | 231/6.2 |

| Total | 1986/100 | 3708/100 |

| Very Bad | Bad | Medium | Good | Very Good | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI Awareness | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n | |||||

| DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | ||

| NO | 241/6.5 | 174/4.7 | 237/6.4 | 239/6.4 | 785/21.2 | 850/22.9 | 1219/32.9 | 1373/37.1 | 1226/33 | 1072/28.9 | 3708 |

| YES | 131/6.6 | 89/4.5 | 91/4.6 | 109/5.5 | 353/17.8 | 354/17.8 | 613/30.9 | 748/37.7 | 798/40.2 | 686/34.5 | 1986 |

| DIVIN | ARHC | |

|---|---|---|

| SI Awareness | n/% | n/% |

| NO | 2455/65.9 | 2455/66 |

| YES | 1411/71.1 | 1434/72.2 |

| Very Bad | Bad | Medium | Good | Very Good | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n | ||||||

| Zone | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | |

| Zone 1 | 24/7.2 | 20/6 | 16/4,8 | 13/3.9 | 64/19 | 54/16 | 109/32.4 | 141/42 | 123/36.6 | 108/32.1 | 336 |

| Zone 2 | 39/6.2 | 22/3.5 | 32/5 | 29/4.6 | 106/16.8 | 111/17.6 | 183/29 | 234/37.1 | 271/43 | 235/37.2 | 631 |

| Zone 3 | 64/6.9 | 43/4.6 | 39/4.2 | 61/6.5 | 166/17.8 | 176/18.9 | 294/31.5 | 340/36.5 | 369/39.6 | 312/33.5 | 932 |

| NULL | 4/4.6 | 4/4.6 | 4/4.6 | 6/6.9 | 17/19.5 | 13/15 | 27/31 | 33/37.9 | 35/40.2 | 31/35.6 | 87 |

| Total | 131 | 89 | 91 | 109 | 353 | 354 | 613 | 748 | 798 | 686 | 1986 |

| Very Bad | Bad | Medium | Good | Very Good | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n | ||||||

| Zone | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | DIVIN | AHRC | |

| Zone 1 | 49/6.4 | 40/5.2 | 48/6.2 | 43/5.6 | 158/20.7 | 193/25.3 | 264/34.6 | 283/37.1 | 243/31.8 | 203/26.6 | 762 |

| Zone 2 | 72/6.2 | 50/4.3 | 70/6.1 | 75/6.5 | 243/21.2 | 256/22.3 | 369/32.2 | 432/37.7 | 391/34.1 | 332/28.9 | 1145 |

| Zone 3 | 103/6.5 | 76/6.5 | 99/6.3 | 103/8.9 | 335/21.3 | 341/29.7 | 514/32.7 | 575/36.6 | 519/33 | 475/30.2 | 1570 |

| NULL | 17/7.3 | 8/7.3 | 20/8.6 | 18/7.7 | 49/21.2 | 60/25.9 | 72/31.1 | 83/35.9 | 73/31.6 | 62/26.8 | 231 |

| Total | 241 | 174 | 237 | 239 | 705 | 850 | 1219 | 1373 | 1226 | 1072 | 3708 |

| SI Awareness | No SI Awareness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone | DIVIN | ARHC | DIVIN | ARHC |

| Good And Very Good | Good And Very Good | Good And Very Good | Good And Very Good | |

| n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | |

| Zone 1 | 232/69 | 249/74.1 | 507/66.4 | 486/63.7 |

| Zone 2 | 454/72 | 469/74.3 | 760/66.3 | 764/65.9 |

| Zone 3 | 663/71.1 | 652/70 | 1033/65.7 | 1050/66.8 |

| DIVIN | n = 1349 | ARHC | n = 1370 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone | Good | Very Good | Good | Very Good | Good | Very Good | Good | Very Good |

| % | % | Delta | Delta | % | % | Delta | Delta | |

| Zone 1 | 32.4 | 36.6 | +4.2 | 42 | 32.1 | +9.9 | ||

| Zone 2 | 29 | 43 | +14 | 37.1 | 37.2 | +0.1 | ||

| Zone 3 | 31.5 | 39.6 | +8.1 | 36.5 | 33.5 | +3 | ||

| Total | +26.3 | +12.8 | ||||||

| SI Topics | Sig |

|---|---|

| DIVIN | 0.260 |

| ARHC | 0.140 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cayolla, R.R.; Quintela, J.A.; Santos, T. “If You Don’t Know Me by Now”—The Importance of Sustainability Initiative Awareness for Stakeholders of Professional Sports Organizations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094917

Cayolla RR, Quintela JA, Santos T. “If You Don’t Know Me by Now”—The Importance of Sustainability Initiative Awareness for Stakeholders of Professional Sports Organizations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094917

Chicago/Turabian StyleCayolla, Ricardo Roseira, Joana A. Quintela, and Teresa Santos. 2022. "“If You Don’t Know Me by Now”—The Importance of Sustainability Initiative Awareness for Stakeholders of Professional Sports Organizations" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094917

APA StyleCayolla, R. R., Quintela, J. A., & Santos, T. (2022). “If You Don’t Know Me by Now”—The Importance of Sustainability Initiative Awareness for Stakeholders of Professional Sports Organizations. Sustainability, 14(9), 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094917