Resident Perceptions of Environment and Economic Impacts of Tourism in Fiji

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable Tourism

1.2. Sustainability in SIDS

1.3. Residents Perceptions towards Tourism Impacts

1.4. Sustainable Tourism Planning Model

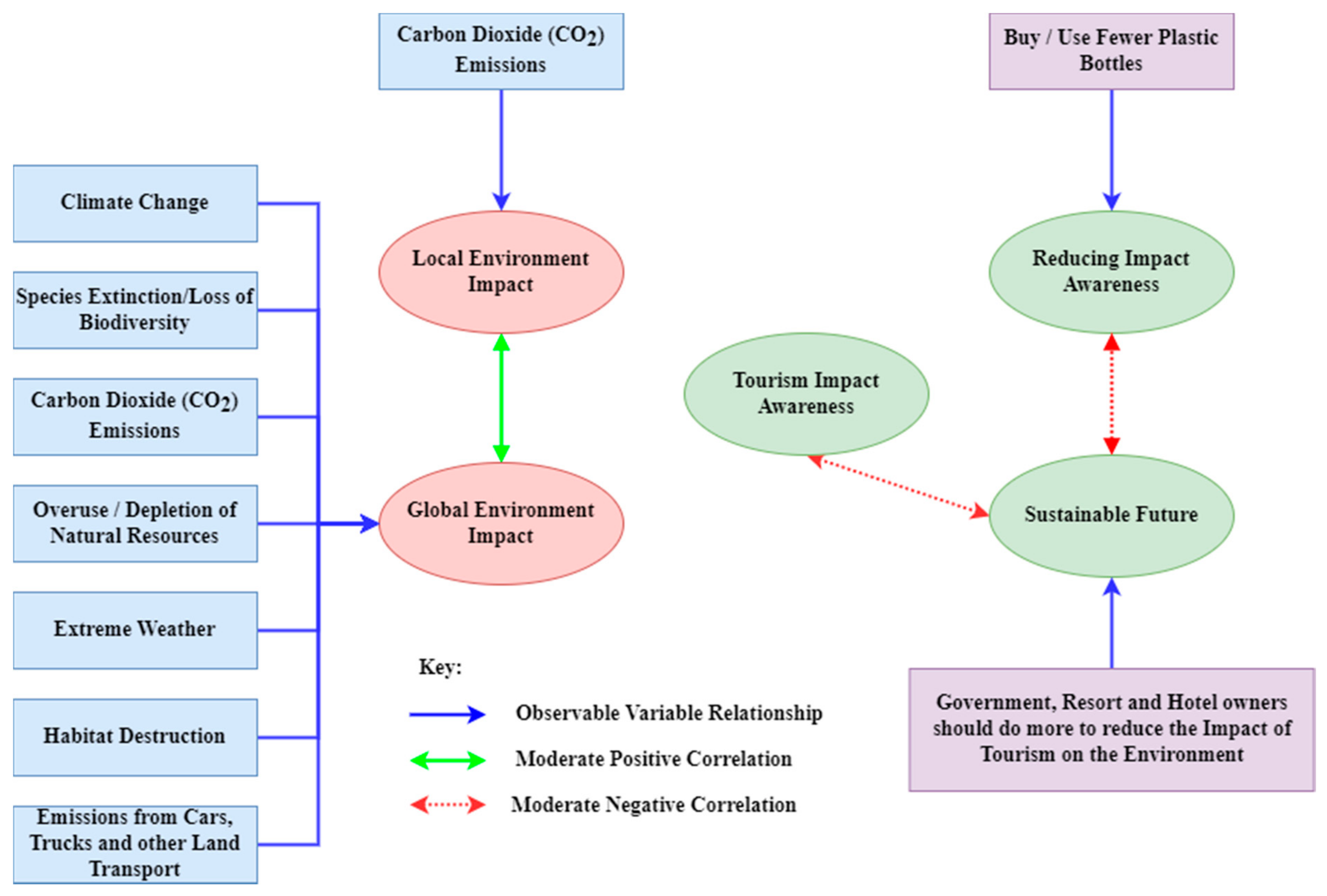

1.5. Model Conceptualization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. SEM Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Thorough Adaption of Sustainability in Education:

- 2.

- Awareness Campaigns Targeting Specific Issues:

- 3.

- Establishment of Uncompromising Sustainable Policies and Acts:

- 4.

- Sustainable Advisory Council (SDC):

- 5.

- Ecotourism

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.J. Sociocultural impacts of tourism on residents of world cultural heritage sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M. The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nepal, R.; Al Irsyad, M.I.; Nepal, S.K. Tourist arrivals, energy consumption and pollutant emissions in a developing economy–implications for sustainable tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Carbon tax, tourism CO2 emissions and economic welfare. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 69, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism’s Carbon Emissions Measured in Landmark Report Launched at COP25. Unwto.org. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/tourisms-carbon-emissions-measured-in-landmark-report-launched-at-cop25 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Birdir, S.; Ünal, Ö.; Birdir, K.; Williams, A.T. Willingness to pay as an economic instrument for coastal tourism management: Cases from Mersin, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R. Sustainable tourism and policy implementation: Lessons from the case of Calvia, Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.; Pforr, C.; Brueckner, M. Factors influencing Indigenous engagement in tourism development: An international perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1100–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.M.; Coromina, L.; Gali, N. Overtourism: Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity-case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Vogt, C.A.; Knopf, R.C. A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. The Effects of Tourism Impacts upon Quality of Life of Residents in the Community. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 5 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Cao, Y.H.; Lin, B.Y. Comparative study on residents’ perception of tourism impact at tourist places. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2005, 15, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakuni, K. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Tourism, Focusing on Ecocecentric Attitudes and Perceptions of Economic Costs: The Case of Iriomote Island, Japan; Park, Recreation and Tourism Resources; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eraqi, M.I. Local communities’ attitudes towards impacts of tourism development in Egypt. Tour. Anal. 2007, 12, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Li, J. Host Perceptions of Tourism Impact and Stage of Destination Development in a Developing Country. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Small island urban tourism: A residents’ perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rughoobur-Seetah, S. Residents’ perception on factors impeding sustainable tourism in sids. Prestig. Int. J. Manag. IT-Sanchayan 2019, 8, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alector-Ribeiro, M.; Pinto, P.; Albino-Silva, J.; Woosman, K.M. Resident’s attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviour: The case of developing islands countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padin, C. A sustainable tourism planning model: Components and relationships. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2012, 24, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padin, C.; Ferro, C.; Wagner, B.; Valera, J.C.; Høgevold, N.M.; Svensson, G. Validating a triple bottom line construct and reasons for implementing sustainable business practices in companies and their business networks. Corp. Gov. 2016, 15, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puczko, L.; Ratz, T. Tourist and resident perceptions of the physical impacts of tourism at Lake Balaton, Hungary: Issues for sustainable tourism management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vita, G.; Katircioglu, S.; Altinay, L.; Fethi, S.; Mercan, M. Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in a tourism development context. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 16652–16663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.T.; Feridun, M.; Kilinc, C. Estimating tourism-induced energy consumption and CO2 emissions: The case of Cyprus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriana, B. Environmental supply chain management in tourism: The case of large tour operators. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunk, R.M.; Gillespie, S.A.; MacLeod, D. Participation and retention in a green tourism certification scheme. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1585–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriñach, J.; Wöber, K. Introduction to the special focus: Cultural tourism and sustainable urban development. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Movono, A.; Pratt, S.; Harrison, D. Adapting and reacting to tourism development: A tale of two villages on Fiji’s Coral Coast. In Tourism in Pacific Islands; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015; pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H. Female empowerment and tourism: A focus on businesses in a Fijian village. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H.; Becken, S. Fijian culture and the environment: A focus on the ecological and social interconnectedness of tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Fox, D. Modelling attitudes to nature, tourism and sustainable development in national parks: A survey of visitors in China and the, U.K. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Chang, C.P. Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbarry, R. Tourism and economic growth: The case of Mauritius. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movono, A. Tourism’s Impact on Communal Development in Fiji: A Case Study of the Socio-Economic Impacts of The Warwick Resort and Spa and The Naviti Resort on the Indigenous Fijian Villages of Votua and Vatuolalai. Master’s Thesis, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji, March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Challenges of sustainable tourism development in the developing world: The case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxey, G.V. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Conference of the Travel and Tourism Research Associations, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. Eskimo tourism: Micro-models and marginal men. In Host and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Tour. Area Life Cycle 2006, 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Unwto.org. 2015. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 3 July 2015).

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S. Sustainable Tourism in Island Destinations; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lück, M. The Encyclopedia of Tourism and Recreation in Marine Environments; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.; Lewis-Cameron, A. Small Island Developing States: Issues and Prospects. In Marketing Island Destinations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boukas, N.; Ziakas, V. A chaos theory perspective of destination crisis and sustainable tourism development in islands: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, D.; Baldacchino, G. Introduction: On island futures. In Island Futures; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graci, S.; Van Vliet, L. Examining stakeholder perceptions towards sustainable tourism in an island destination. The Case of Savusavu, Fiji. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Russell, M. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: Comparing the impacts of small-and large-scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brau, R.; Lanza, A.; Pigliaru, F. How Fast Are the Tourism Countries Growing? The Cross-Country Evidence; Centre for North South Economic Research, University of Cagliari: Cagliari, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism composite indicators: A dynamic evaluation to manage changes in sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1403–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catibog-Sinha, C. Biodiversity conservation and sustainable tourism: Philippine initiatives. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, G.; Wagner, B. A process directed towards sustainable business operations and a model for improving the GWP-footprint (CO2e) on Earth. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2011, 22, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Wagner, B. Transformative Business Sustainability: Multi-Layer Model and Network of e-Footprint Sources. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgevold, N.M. A Corporate Effort towards a Sustainable Business Model: A Case Study from the Norwegian Furniture Industry. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambra-Fierro, J.; Ruiz-Benítez, R. Sustainable Business Practices in Spain: A Two-Case Study. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, M.A. Minimizing the Business Impact on the Natural Environment: A Case Study of Woolworths South Africa. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgevold, N.M.; Svensson, G. A business sustainability model: A European case study. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigram, J.J. Sustainable tourism-policy considerations. J. Tour. Stud. 1990, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, C.; Padin, C.; Høgevold, N.; Svensson, G.; Varela, J.C. Validating and expanding a framework of a triple bottom line dominant logic for business sustainability through time and across contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grah, B.; Dimovski, V.; Peterlin, J. Managing sustainable urban tourism development: The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2020, 12, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Lange, D.E. Start-up sustainability: An insurmountable cost or a life-giving investment? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach; National Parks Today: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Green Guide for Tourism: Methuen, MA, USA, 1985; Volume 31, pp. 224–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.R.; Richards, G. Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R. Local involvement in managing tourism. In Tourism in Destination Communities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, D.G. Community participation in tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. Development issues in destination communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.S.; Mäenpää, M. An overview of the challenges for public participation in river basin management and planning. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2008, 19, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, P.; Gössling, T. The worth of values–a literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.R.; Slater, D.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Romi, A.M. Beyond “does it pay to be green?” A meta-analysis of moderators of the CEP–CFP relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albertini, E. Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G. When does it pay to be good–A contingency perspective on corporate social and financial performance: Would it work? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1062–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.C.; Shih, Y.N.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, Y. Does corporate social performance pay back quickly? A longitudinal content analysis on international contractors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Fiji: 2020 Annual Research Key Highlights. 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact/moduleId/704/itemId/110/controller/DownloadRequest/action/QuickDownload (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Ayala, H. The Unresearched Phenomenon of “Hotel Circuits”. Hosp. Res. J. 1993, 16, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Tourism Fiji 2019. Available online: https://www.fiji.travel/us/about-tourism-fiji (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- United Nations Pacific. Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Fiji. 2020. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/fiji/docs/SEIA%20Fiji%20Consolidated%20Report.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- International Finance Corporation. IFC Fiji COVID-19 Business Survey: Tourism Focus. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/4fc358f9-5b07-4580-a28c-8d24bfaf9c63/Fiji+COVID-19+Business+Survey+Results+-+Tourism+Focus+Final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=ndnpJrE (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Tourism Fiji. Available online: https://www.fiji.travel/us/information/transport (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Fiji’s Earnings from Tourism. Available online: https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/index.php/latest-releases/tourism-and-migration/earnings-from-tourism/925-fiji-s-earnings-from-tourism-december-quarter-and-annual-2018 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Berno, T. Bridging Sustainable Agriculture and Sustainable Tourism to Enhance Sustainability; Sustainable Development Policy and Administration; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, B.C.; Narayan, P.K. Reviving growth in the Fiji islands: Are we swimming or sinking. Pac. Econ. Bull. 2008, 23, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, R. The rough global tide and political storm in Fiji call for swimming hard and fast but with a different stroke. Pac. Econ. Bull. 2009, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, P.K.; Prasad, B.C. Fiji’s sugar, tourism and garment industries: A survey of performance, problems and potentials. Fijian Stud. 2003, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M. Challenges and Issues in Pro-Poor Tourism in South Pacific Island Countries: The Case of Fiji Islands; School of Economics, University of the South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Veit, R. Tourism, Food Imports and the Potential of Import-Substitution Policies in Fiji; Fiji AgTrade, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests: Suva, Fiji, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, T.A. Indigenous and democratic decision-making: Issues from community-based ecotourism in the Boumā National Heritage Park, Fiji. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeral, E. Tourism forecasting performance considering the instability of demand elasticities. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Review April 2020. Available online: https://www.rbf.gov.fj/getattachment/Publications/Economic-Review-April-2020/Economic-Review-April-2020-(11).pdf?lang=en-US (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S.; Mentzer, J.T. Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. J. Bus. Logist. 1999, 20, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelter, J.W. The analysis of covariance structures: Goodness-of-fit indices. Sociol. Methods Res. 1983, 11, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, S.; McMillan, J.H. Research in Education: A Conceptual Introduction; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. A Note on Multiple Sample Extensions of the RMSEA Fit Index. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2009, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Pizam, A.; Milman, A. Social impacts of tourism: Host perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilsson, S.; Hjelm, O. Managing indirect environmental impact within local authorities’ standardized environmental management systems. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littau, P.; Jujagiri, N.J.; Adlbrecht, G. 25 years of stakeholder theory in project management literature (1984–2009). Proj. Manag. J. 2010, 41, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzi, L.; Boragno, V.; Serrano-Bernardo, F.A.; Verità, S.; Rosúa-Campos, J.L. Environmental management policy in a coastal tourism municipality: The case study of Cervia (Italy). Local Environ. 2011, 16, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Education Level | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| None | 3 | 1.0 |

| Primary | 1 | 0.3 |

| Secondary | 83 | 27.2 |

| Certificate | 25 | 8.2 |

| Diploma | 61 | 20.0 |

| Degree | 112 | 36.7 |

| Master’s | 17 | 5.6 |

| Total | 302 | 99.0 |

| No response | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 305 | 100 |

| Usable Responses | 298 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 285 | 1.59 | 0.493 |

| Education | 298 | 4.85 | 1.336 |

| EnvImp1 | 290 | 1.97 | 0.174 |

| EnvImp2 | 296 | 3.56 | 0.983 |

| EnvImp3 | 296 | 3.50 | 1.173 |

| EnvImp4 | 298 | 3.74 | 0.993 |

| EnvImp5 | 298 | 3.10 | 1.163 |

| EnvImp6 | 298 | 4.08 | 0.956 |

| EnvImp7 | 298 | 3.35 | 1.094 |

| EnvImp8 | 298 | 2.70 | 1.159 |

| EnvImp9 | 298 | 2.71 | 1.278 |

| EnvImp10 | 297 | 3.22 | 1.181 |

| EnvImp11 | 297 | 2.77 | 1.349 |

| EnvImp12 | 296 | 3.77 | 1.123 |

| EnvImp13 | 296 | 3.47 | 1.015 |

| EnvImp14 | 297 | 3.75 | 1.048 |

| EnvImp15 | 297 | 3.74 | 0.953 |

| EnvImp16 | 296 | 3.31 | 1.101 |

| EnvImp17 | 297 | 3.58 | 1.082 |

| EnvImp18 | 297 | 3.84 | 1.012 |

| EnvImp19 | 297 | 3.73 | 1.083 |

| EnvImp20 | 297 | 3.76 | 1.077 |

| EnvImp21 | 295 | 3.64 | 1.130 |

| EnvImp22 | 295 | 2.57 | 1.116 |

| EIG1 | 294 | 4.16 | 0.985 |

| EIG2 | 295 | 4.01 | 0.933 |

| EIG3 | 295 | 4.03 | 0.976 |

| EIG4 | 295 | 3.97 | 0.947 |

| EIG5 | 295 | 3.75 | 1.068 |

| EIG6 | 295 | 3.86 | 1.142 |

| EIG7 | 295 | 3.54 | 1.277 |

| EIG8 | 294 | 3.56 | 1.002 |

| EIG9 | 295 | 3.15 | 1.542 |

| EIG10 | 295 | 3.81 | 1.189 |

| EIG11 | 294 | 3.94 | 1.064 |

| EIG12 | 294 | 3.05 | 1.226 |

| EIG13 | 295 | 3.99 | 1.103 |

| EIG14 | 295 | 4.07 | 1.018 |

| EIG15 | 295 | 3.66 | 1.044 |

| EIG16 | 295 | 3.95 | 0.952 |

| EIG17 | 295 | 3.65 | 1.227 |

| EIG18 | 294 | 3.92 | 1.132 |

| EIG19 | 295 | 3.96 | 1.033 |

| EIG20 | 295 | 3.77 | 1.119 |

| EIG21 | 295 | 3.95 | 1.066 |

| EIG22 | 295 | 4.01 | 1.058 |

| EIG23 | 295 | 3.15 | 1.329 |

| IMPU1 | 287 | 1.72 | 0.590 |

| IMPU2 | 297 | 1.71 | 0.454 |

| IMPU3 | 297 | 1.58 | 0.495 |

| IMPU4 | 297 | 1.76 | 0.429 |

| IMPU5 | 297 | 1.65 | 0.478 |

| IMPU6 | 297 | 1.70 | 0.460 |

| IMPU7 | 297 | 1.67 | 0.470 |

| IMPU8 | 297 | 1.52 | 0.501 |

| IMPU9 | 297 | 1.49 | 0.501 |

| IMPU10 | 297 | 1.71 | 0.456 |

| RIA1 | 282 | 1.83 | 0.380 |

| RIA2 | 295 | 1.65 | 0.478 |

| RIA3 | 295 | 1.92 | 0.279 |

| RIA4 | 295 | 1.88 | 0.320 |

| RIA5 | 295 | 1.53 | 0.500 |

| RIA6 | 295 | 1.39 | 0.489 |

| RIA7 | 295 | 1.31 | 0.463 |

| RIA8 | 295 | 1.45 | 0.499 |

| RIA9 | 295 | 1.63 | 0.483 |

| RIA10 | 295 | 1.69 | 0.464 |

| RIA11 | 294 | 1.52 | 0.500 |

| RIA12 | 295 | 1.84 | 0.363 |

| RIA13 | 295 | 1.53 | 0.500 |

| RIA14 | 295 | 1.45 | 0.498 |

| RIA15 | 295 | 1.36 | 0.481 |

| RIA16 | 295 | 1.51 | 0.501 |

| RIA17 | 295 | 1.78 | 0.413 |

| RIA18 | 295 | 1.82 | 0.387 |

| Eco1 | 278 | 1.68 | 0.510 |

| Eco2 | 286 | 1.89 | 0.311 |

| Eco3 | 286 | 1.88 | 0.320 |

| Eco4 | 273 | 1.56 | 0.497 |

| SusFut1 | 286 | 1.95 | 0.223 |

| SusFut2 | 285 | 1.35 | 0.477 |

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 101 | 35.2 |

| Yes | 165 | 57.5 | |

| No than Yes | 21 | 7.3 | |

| Total | 287 | 100.0 | |

| Missing | 999 | 11 | |

| Total | 298 | ||

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 144 | 48.5 |

| Yes | 153 | 51.5 | |

| Total | 297 | 100.0 | |

| Missing | 999 | 1 | |

| Total | 298 | ||

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 151 | 50.8 |

| Yes | 146 | 49.2 | |

| Total | 297 | 100.0 | |

| Missing | 999 | 1 | |

| Total | 298 | ||

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 49 | 17.4 |

| Yes | 233 | 82.6 | |

| Total | 282 | 100.0 | |

| Missing | No response | 16 | |

| Total | 298 | ||

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 186 | 65.3 |

| Yes | 99 | 34.7 | |

| Total | 285 | 100.0 | |

| Missing | No Response | 13 | |

| Total | 298 | ||

| Latent Variables | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|

| Local Environment Impact (LEI) | 0.57 |

| Global Environment Impact (GEI) | 0.52 |

| Reducing Impact Awareness (RIA) | 0.54 |

| Sustainable Future (SF) | 0.55 |

| Latent Variables | Local Environment Impact | Global Environment Impact | Reducing Impact Awareness | Sustainable Future |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Environment Impact | 0.76 | |||

| Global Environment Impact | 0.64 | 0.72 | ||

| Reducing Impact Awareness | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.73 | |

| Sustainable Future | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.31 | 0.74 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prasad, N.S.; Kumar, N.N. Resident Perceptions of Environment and Economic Impacts of Tourism in Fiji. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094989

Prasad NS, Kumar NN. Resident Perceptions of Environment and Economic Impacts of Tourism in Fiji. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094989

Chicago/Turabian StylePrasad, Navneel Shalendra, and Nikeel Nishkar Kumar. 2022. "Resident Perceptions of Environment and Economic Impacts of Tourism in Fiji" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094989

APA StylePrasad, N. S., & Kumar, N. N. (2022). Resident Perceptions of Environment and Economic Impacts of Tourism in Fiji. Sustainability, 14(9), 4989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094989