What Brought Me Here? Different Consumer Journeys for Practices of Sustainable Disposal through Takeback Programmes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“And what am I going to do with this now? Where am I going to dispose of it? I don’t want to throw it in the garbage.”

1.1. Sustainable Disposal Behaviour

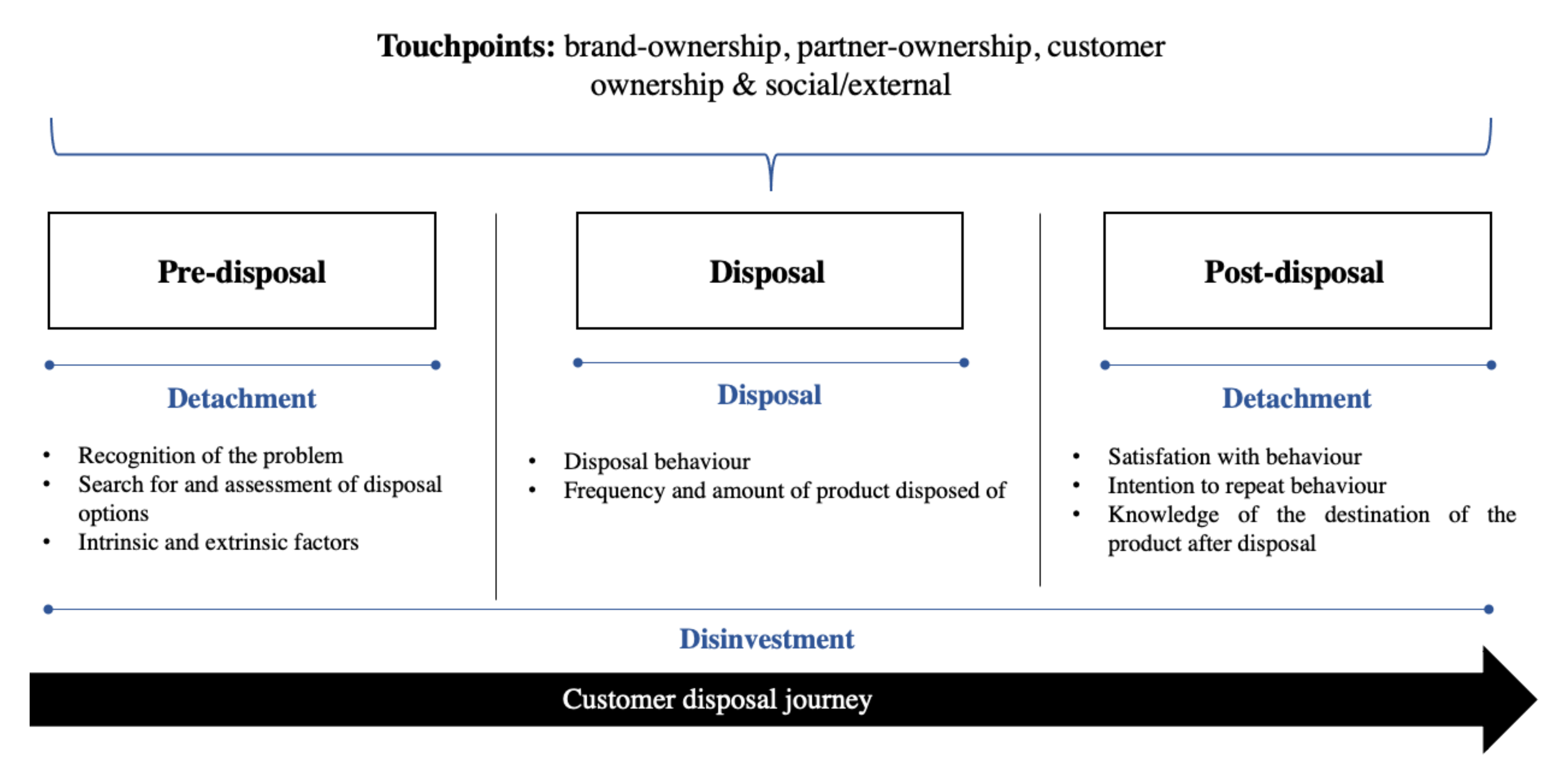

1.2. Integrative Framework Proposal: Disposal as a Journey

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Field

2.2. Data Collection Techniques

2.3. Data Analysis Procedures

3. Analysis of the Disposal Journey

3.1. The Disposal Journey of Wallet Customers

3.1.1. Pre-Disposal

3.1.2. Disposal

3.1.3. Post-Disposal

3.2. The Disposal Journey of the Customer of Coffee Capsules

3.2.1. Pre-Disposal

3.2.2. Disposal

3.2.3. Post-Disposal

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Script Questions

Appendix A.1. Part 1—Characteristics of the Decision Maker

- (1)

- Tell me a little about your view about sustainability. What does sustainability represent to you?

- (2)

- Have you ever taken a course or had any classes in your school or academic training about sustainability? Could you tell me more about it?

- (3)

- Do you think about issues related to sustainability in your day-to-day consumption?

- (4)

- Tell me if you are involved in any social cause (NGO, volunteering, etc.).

- (5)

- For day-to-day purchases, do you preferably buy from small producers or from large brands/networks?

- (6)

- How do you identify the consumption of the people you live with? Is it similar or different from yours? Could you give me some examples?

Appendix A.2. Part 2—Disposal Journey Elements

- (1)

- What disposal methods have you used to dispose of wallets/coffee capsules?

- (2)

- Tell me about the first time you used the Dobra/Terra Cycle takeback program. When did you realise that you could dispose of the product through the takeback program?

- (3)

- Tell me about the last time you use the Dobra/Terra Cycle takeback program. Do you continue to dispose of wallets/coffee capsules through the takeback program? How often?

- (4)

- How do you store the wallet/coffee capsule until disposal it?

- (5)

- Where do you dispose of the wallet/coffee capsules? How far is the location from your home? Do you receive any monetary return when you dispose of the wallets/coffee capsules?

- (6)

- Do you know what is done with the product after you dispose it? How do you feel after disposing of it through the takeback program?

Appendix A.3. Part 3—Identification of Touchpoints during the Journey

- (1)

- Do you follow Dobra’s/Terra Cycle’s social networks and website? With what frequency?

- (2)

- Do you usually dispose alone or accompanied?

- (3)

- Do you have friends or family members who are part of the Dobra/Terra Cycle program? Tell me a little more about it, please.

- (4)

- Have you read any news about Dobra’s/Terra Cycle takeback program on any website/newspaper/blog/social network that wasn’t from the brand?

Appendix B. Interviewees

References

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, J.; Subramoniam, R.; Govindan, K.; Huisingh, D. Closed-loop supply chain management: From conceptual to an action oriented framework on core acquisition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.K.; Pedersen, E.R.G. Toward circular economy of fashion: Experiences from a brand’s product take-back initiative. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Gentry, J. The Role of Style versus Fashion Orientation on Sustainable Apparel Consumption. J. Macromark. 2019, 39, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.K. Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. Laws 2019, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fletcher, K. Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuabara, L.; Paucar-Caceres, A.; Burrowes-Cromwell, T. Consumers’ values and behaviour in the Brazilian coffee-in-capsules market: Promoting circular economy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7269–7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Priorities (MSI 2020–2022). Available online: https://www.msi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/MSI_RP20-22.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Canfield, D.D.S.; Basso, K. Integrating Satisfaction and Cultural Background in the Customer Journey: A Method Development and Test. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2016, 29, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.; Price, L.L. Consumer journeys: Developing consumer-based strategy. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Signori, P.; Gozzo, I.; Flint, D.J.; Milfeld, T.; Nichols, B.S. Sustainable customer experience: Bridging theory and practice. In The Synergy of Business Theory and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 131–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; Arévalo-Chávez, P. Consumer Behavior in the Disposal of Products: Forty Years of Research. J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigöllü, E.; Hou, C.; Ertz, M. Sustainable product disposal: Consumer redistributing behaviors versus hoarding and throwing away. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, M.B. Sustainability in marketing: A systematic review unifying 20 years of theoretical and substantive contributions (1997–2016). AMS Rev. 2018, 8, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Dadzie, C.A.; Chaudhuri, H.R.; Tanner, T. Self-control and sustainability consumption: Findings from a cross cultural study. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, M. Critical sustainable consumption: A research agenda. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Boks, C.; Pettersen, I.N. Consumption in the Circular Economy: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parajuly, K.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Muldoon, O.; Kuehr, R. Behavioral change for the circular economy: A review with focus on electronic waste management in the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Kronegger, L. Environmental consciousness of European consumers: A segmentation-based study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I.; Buerke, A.; Kirchgeorg, M.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.P. Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Rev. 2013, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.Y.; Jo, G.Y.; Oh, M.J. The persuasive effect of competence and warmth on clothing sustainable consumption: The moderating role of consumer knowledge and social embeddedness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norum, P.S. Trash, Charity, and Secondhand Stores: An Empirical Analysis of Clothing Disposition. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2015, 44, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Creery, S. The consumption and disposition behaviour of voluntary simplifiers. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poppelaars, F.; Bakker, C.; van Engelen, J. Design for Divestment in a Circular Economy: Stimulating Voluntary Return of Smartphones through Design. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trudel, R.; Argo, J.J.; Meng, M.D. The Recycled Self: Consumers’ Disposal Decisions of Identity-Linked Products. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Lynes, J.; Young, S.B. Fashion interest as a driver for consumer textile waste management: Reuse, recycle or disposal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; del Val Núñez, M.T. Clothing disposition by gifting: Benefits for consumers and new consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4975–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Berning, C.K.; Dietvorst, T.F. What about disposition? J. Mark. 1977, 41, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.W. A Proposed Paradigm for Consumer Product Disposition Processes. J. Consum. Aff. 1980, 14, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, T.C.; McCcnocha, D.M. Consumer household materials and logistics management: Inventory ownership cycle. J. Consum. Aff. 1996, 30, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxendale, S.; Macdonald, E.K.; Wilson, H.N. The Impact of Different Touchpoints on Brand Consideration. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tueanrat, Y.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. Going on a journey: A review of the customer journey literature. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Nenkov, G.Y.; Gonzales, G.E. Knowing What It Makes: How Product Transformation Salience Increases Recycling. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Qualidade na Pesquisa Qualitativa: Coleção Pesquisa Qualitativa; Bookman Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.; Townsend, K. Choosing participants. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions; Cassel, C., Cunliffe, A.L., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. Content Analysis; Edições: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011; Volume 70, ISBN 978-8562938047. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Análise de Dados Qualitativos: Coleção Pesquisa Qualitativa; Bookman Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strategy Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dommer, S.L.; Winterich, K.P. Disposing of the self: The role of attachment in the disposition process. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K. Consumers’ clothing disposal behaviour–a synthesis of research results. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer Attitude towards Sustainability of Fast Fashion Products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dobra Wallets | Terra Cycle Coffee Capsules | |

|---|---|---|

| Pré-Disposal | ||

| Behaviours | ||

| Recognition of the Problem | ✓ | ✓ |

| Search for and assessment of disposal options | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intrinsic and extrinsic factors | ✓ | ✓ |

| Detachment | ✓ | ✗ |

| Influence of Touchpoints | ||

| Brand-Ownership | ✓ | ✓ |

| Customer-Ownership | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social/External | ✓ | ✗ |

| Partner- Ownership | ✗ | ✗ |

| Disposal | ||

| Behaviours | ||

| Disposal Behaviour | ✓ | ✓ |

| Frequency of product disposed of | ✓ | ✓ |

| Amount of product disposed of | ✓ | ✓ |

| Disposal | ✓ | ✓ |

| Influence of Touchpoints | ||

| Brand-Ownership | ✗ | ✗ |

| Social/External | ✗ | ✗ |

| Partner-Ownership | ✗ | ✗ |

| Customer-Ownership | ✓ | ✓ |

| Post-disposal | ||

| Behaviours | ||

| Satisfaction with behaviour | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intention to repeat behaviour | ✓ | ✓ |

| Knowledgle of the destination of the product after disposal | ✓ | ✓ |

| Detachment | ✓ | ✗ |

| Influence of Touchpoints | ||

| Brand-Ownership | ✓ | ✗ |

| Customer-Ownership | ✓ | ✓ |

| Partner-Ownership | ✗ | ✗ |

| Social/External | ✗ | ✗ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radtke, M.L.; de Almeida, S.O.; Espartel, L.B. What Brought Me Here? Different Consumer Journeys for Practices of Sustainable Disposal through Takeback Programmes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095003

Radtke ML, de Almeida SO, Espartel LB. What Brought Me Here? Different Consumer Journeys for Practices of Sustainable Disposal through Takeback Programmes. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095003

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadtke, Manoela Lawall, Stefânia Ordovás de Almeida, and Lélis Balestrin Espartel. 2022. "What Brought Me Here? Different Consumer Journeys for Practices of Sustainable Disposal through Takeback Programmes" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095003

APA StyleRadtke, M. L., de Almeida, S. O., & Espartel, L. B. (2022). What Brought Me Here? Different Consumer Journeys for Practices of Sustainable Disposal through Takeback Programmes. Sustainability, 14(9), 5003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095003