Abstract

The Lantern Festival constitutes a specific tradition that originated from a long-term evolved culture. Should the festival only consist of a large number of installations and visitors? This study aims to assess the Taiwan Lantern Festival (TLF) in terms of government procurements between 2016 and 2020 according to the classification of tender projects. The classifications contribute to a comparison of the similarities and diversities in respect to the major challenge of the number of visitors exceeding 10 million in two weeks. The 140–234 tender projects each year presented a 76% increment of the budget for services, financing, and construction. The similarities and differences made each year’s TLF a local-identity-rich event. Shared similarities accounted for approximately 54% of all 654 tender items and 66% of the budget. The shared main items demonstrated their importance in transferring the TLF experience to the host city of the subsequent year. The interpretation of procurement contributed to the novelty of TLF classifications and the shared project similarities and diversities through the government acting as a curator. The findings contributed to an evolved model of classification for local situation and TLF experience transfer, evolved measures for diversities and shared similarities, and an evolved instrumentation for traditions.

1. Introduction

The Lantern Festival has been celebrated at the first full moon in the Chinese Lunar New Year since the Han Dynasty. In addition to lantern exhibitions, the festival is usually held with events that have evolved with cultural meanings. The Lantern Festival has been designated as a tourism event since 1977. In 1990, temple-oriented festival lantern installations were gathered to create the Taiwan Lantern Festival (TLF), and this gradually evolved into one of the 12 large-scale folk festivals in Taiwan in 2001 [1]. It was then packaged into a festival week, including the three days before and three days after the day of the festival (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Installations of the 2016 Taiwan Lantern Festival (left) and local event (right).

The TLF is famous for its tradition that evolved from the history, policies, and host city’s characteristics over a period of 31 years [1,2,3,4,5] in Taiwan. As an island-wide festival with a centered layout of installations, its scale is represented by its large number of installations, involved parties, and numbers of visiting people of all ages in a short period of time, with its timing following the Chinese New Year and the academic winter break. Since 1977, the Lantern Festival, on the 15th of January of the Lunar Year, has also been a tourism festival that relates to a series of events at the same period of time. Each festival represents a collective event of religion, culture, and entertainment. This cultural preservation has created important measures for intangible traditions.

Collaboration was achieved based on government-oriented fundraising and execution mechanisms, such as procurement, for event-related projects. In 1999, the Government Procurement Law was issued for a fair, open, and efficient procurement procedure [6]. After years of modification, this law specifies all of the official-led projects and purchasing operations for property and labor, with clear specifications for administrative appointments and hiring for engineering projects, financial buy-ins, customization, rentals, and services [7]. This legal mechanism has been followed for years.

1.1. The Role of TLF

Festivals that incorporate government assistance have become an important tourism strategy in promoting regional economic effects [8]. The Tourism Bureau of the Ministry of Transportation and Communications of Taiwan was established in 1956, with affiliated departments in each city and county. This bureau manages national scenic spots, tourist centers, local cultural activities, and associated festival events.

The evolving tourism in Taiwan is closely connected to the historical development of policies and the annual TLF tourist population. TLF, which started in Taipei, is hosted by a different city every year. Almost every city or county attempts to be the host to obtain the festival-related economic benefits. Similar local events are usually promoted by major cities at a smaller scale after hosting the TLF as a sustainable strategy for promoting local tourism. To promote the brand and reduce the gap between the north and the south, the preparation period has been prolonged from 1 to 2 years since 2017, with the host city announced 2 years earlier. Moreover, related promotional efforts included a one-hour worldwide television show broadcast on the Discovery® Channel in 2007.

TLF identity is shared by the entire island as a new brand. The island-wide promotion places it at the top of the festival hierarchy, with associated local identities gathered from different cities. Location-dependent or -independent promotion makes it one of the 12 most important festivals in Taiwan, with unique cultural activities implemented by an efficient government administrative procurement model by today’s standards.

The evolvement of the TLFs came from interactions between the traditions, policies, and the management of created, displayed, and reactivated artifacts. Exhibitions were made in static or dynamic 3D form from staged displays on the ground level or the water surface of ponds or rivers, mobile displays of parades, or air shows comprising UAV fleets, flying lanterns, or fireworks. The experience of interaction can also be extended to a virtual world with apps on hand-held devices in VR and AR, as well as off-site access from the internet with the use of QR codes.

1.2. Visiting Populations

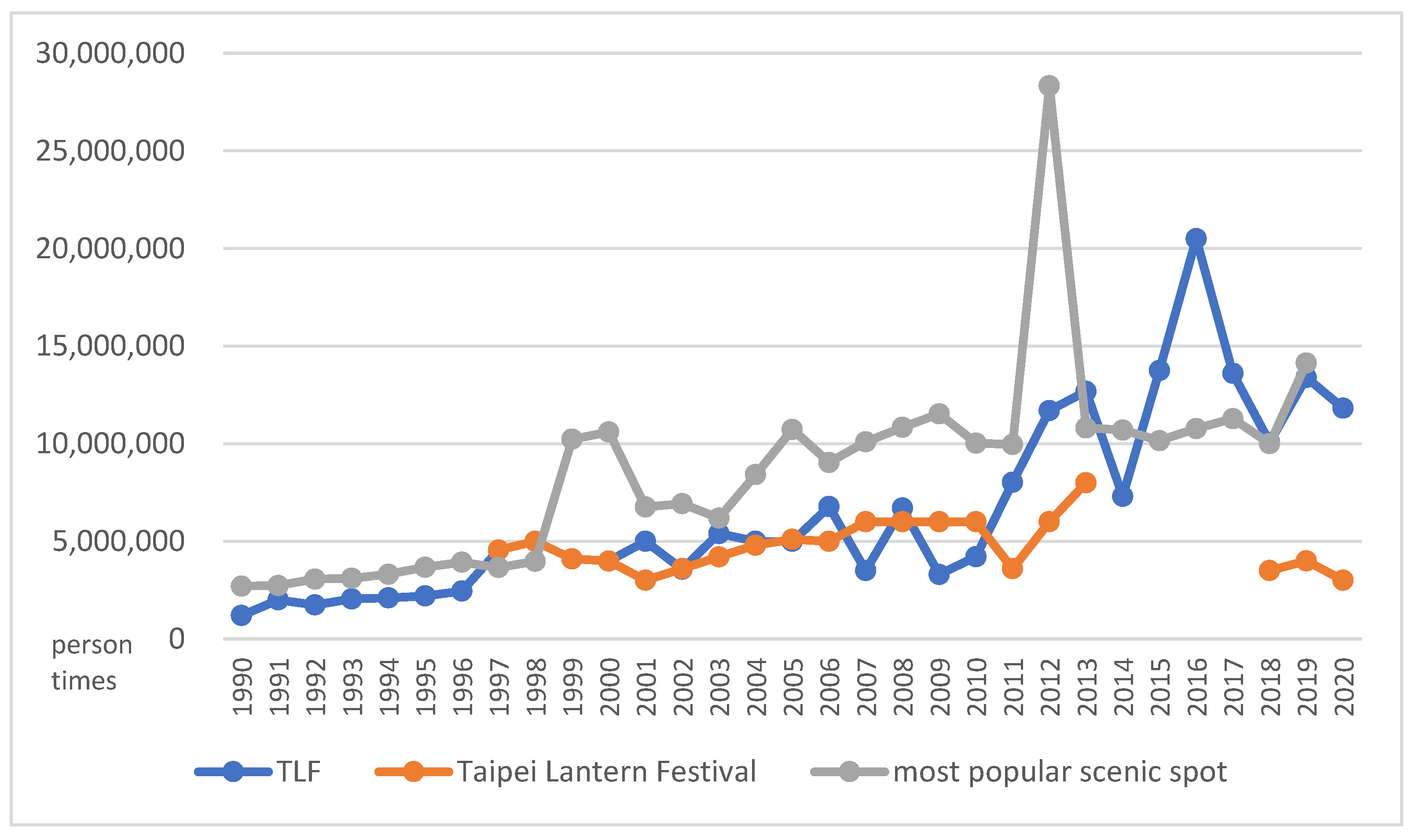

The number of visitors attracted by an event constitutes the most direct assessment of public popularity. To present the scale of the festival and to identify the influence of crowds, populations were compared between the TLF, the Taipei Lantern Festival, and the most popular scenic spot (Figure 2), based on data obtained from the tourist bureau [9]. The numbers were collected and cross-confirmed from news media and government reports. In the festival’s early days, visitors quickly reached 1 million in three days. Since 2012, the numbers and days increased gradually to over 10 million in two weeks. Both national and local lantern festivals are held at about the same time. Multiple activities usually take place in parallel with the Lantern Festival for the synergistic effects of popularity and reputation in terms of local culture, identity, and cuisines.

Figure 2.

The visitor numbers of the TLF, the Taipei Lantern Festival, and the most popular scenic spot.

Taking the Taipei Lantern Festival and TLF for comparison, the former had more visitors in 2002, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2010 when the TLF host cities faced the disadvantages of connecting traffic, underexposed promotion, a less mature tourism market, and/or fewer residences than Taipei. In 2003, Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall was the most popular sightseeing location and the same location for the Lantern Festival. The number of visitors in nine days equaled half of the annual population. However, the number was still lower than that of the TLF held in Taichung. No population data were available between 2014 and 2017 in Taipei. The numbers of TLF visitors between 2015 and 2018 were higher than those of the most popular sightseeing locations. Dapeng Bay, where the TLF was hosted in 2019, had 95% of its annual visitors in 13 days. Comparing the number of visitors between February 2018 (58,490) and February 2019 (8,552,367), it increased approximately 146.22 times. The 2016 TLF in Taoyuan had a record-high number of visitors of 20.5 million in two weeks, compared to Taiwan’s population of 23.58 million.

1.3. Research Goal

This study aims to assess the TLF from the perspective of the measures for government procurements between 2016 and 2020 by exploring the major types of tender projects, their similarities, and diversities.

Cultural assets are classified into tangible and intangible heritages [10]. Since the scale of the TLF has exceeded that of most local events, it is expected that all the TLFs were managed in the same process. However, certain pertinent questions arise, such as if the government assimilates traditions with the settings of the large-scale Lantern Festival. The Lantern Festival should be supported by government e-procurement. How have culture and event management been reflected in the procurement items with the unique characteristics of each year’s tender projects?

2. Related Studies

Event products have been offered since humankind has existed [11]. The numbers, frequencies, and types of events have increased over time [12] in both developed and less-developed countries [13] and have played a major role in the celebration of a community [14]. Social potential was created even by small-scale sports events related to cultural heritage [15] to promote a host city’s image. An event image is important for creating the intention to revisit. A positive image will lead to a higher number of visitors intending to revisit the event [16].

Event management involves brand study, target audience identification, and coordination of events on different scales. The event management body of knowledge (EMBOK) comprises dimensions of domains, phases, and processes [17], with the core values of the framework closely connected to ticketing, transportation, human resources, budgeting, marketing and public relations, and risk management [18]. The topics include rich contents in niche areas (sports, themed events, and weddings) [19,20], safety/security, understanding of event experiences, and green events [21], and social media and IT [22]. An event manager plans and executes an event from brand building, budgeting, and marketing, to communication strategy, by applying collaboration models [23], communication models in city branding [24], and/or marketing strategies [25].

Event management is attracting increasing attention in both academia and tourism development. The extant literature has been continually growing with a diversity of theoretical and practical implications for contemporary hospitality management research [26]. Related progress created insightful views of the tourism industry [27]. Overall growth has formed subsectors, such as the events industry, which have been shown to offer a variety of unique career opportunities [28,29]. The industry has become widely recognized [30], increasingly professional [31], and economically beneficial in both domestic and international markets [32]. This profile has been expressed within the media and communities [33]. A majority of this growth has been contributed to by mega-events of the UK’s event industry for international practices and production skills [34].

The impact of technologies is connected to how events are experienced and managed [35], and enable one to understand event stakeholders’ motives in event delivery [36], enhanced event involvement [35], event administration [37], the shape of an environment [38], and the maintenance and honoring of traditions in events [39]. Studies have been performed regarding research methods, data collection, data analysis procedures, and types of event management [40], even when the internet was in its relative infancy. The number of tourism IT publications grew rapidly in the second half of the 2000s, when mobile phones increasingly facilitated interactions between people, organizations, information, and technology [41].

Festivals and events create major economic impacts, with significant spending by both visitors and vendors [42]. Event funds are required to drive regional repetitive visits and increase partnerships [43], with proposals evaluated based on their impacts on the economy, significant cultural benefits, off-island visits [44], the design and implementation of plans related to eligibility, procurement method, tasks for cultural expression, and time schedule [45]. Procurement information can be found and accessed from many government agencies. Tendering procedures can be applied as a two-bid system, with technical bids and financial bids [46]. To provide assistance, festival-related information is usually delivered with guidelines for sustainable tourism, as well as for ensuring a productive connection with local partnerships and cultural products [47]. An online trade fair database is also provided for exhibition items and related industries in transportation, medical care, education, and services [48]. A specific agent is frequently designated for open solicitation requests with comprehensive, fair, and impartial processes [49] in a series of lists under the category of procurement management [50].

Sustainable development of festival tourism brings attention to the social, cultural, and political influences on communities [51] and takes local stakeholders as partners [52,53]. The products of cultural entities for exchange in culture services are immaterial, impermanent, and diversified [54,55]. Events (e.g., music festivals and sporting events) represent one of the most characteristic indicators of mass cultural consumption [56]. The connection between cultural services and sustainable consumption should be made seamlessly [57]. Ethical purchases of cultural services should be sustainably consumed to lessen the environmental impact [58,59,60] to buildings, transportation infrastructure, communities, and cities, with proposed designs and constructions prepared by government procurements. Both tangible and intangible heritages may be merged with conflicts [61,62], even at the management scale of a historic building under a concern for sustainability [63].

3. Methodology

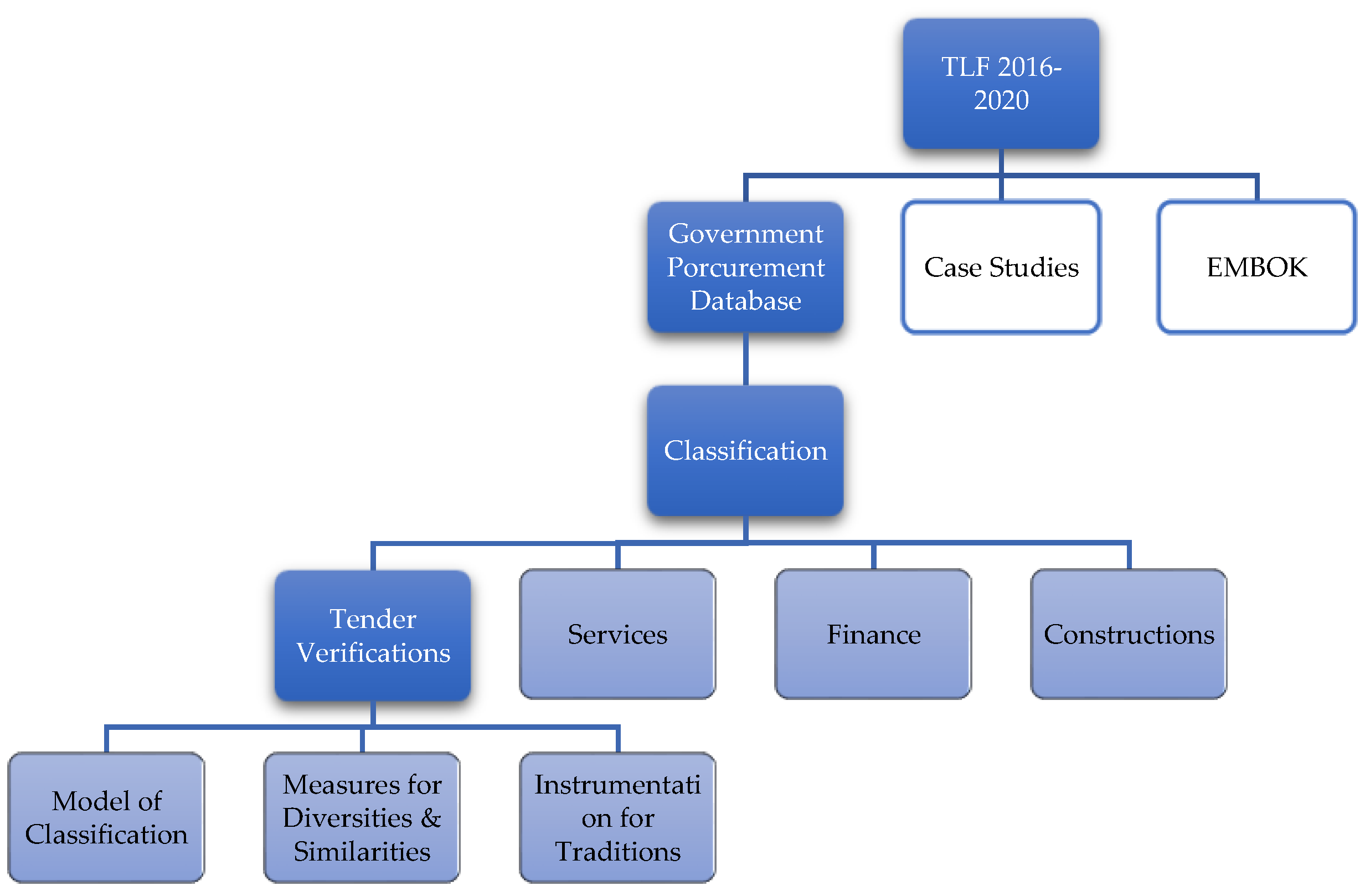

It is expected that all the TLFs were managed with the same process. To confirm this assumption, we assessed festivals according to the measures contributed by the TLF government procurement records (Figure 3). This study was narrowed down to the procurement information from between 2016 and 2020 in terms of the classifications and categories of government e-procurement records by awarded and non-awarded tenders.

Figure 3.

Research framework and flowchart.

Consistency checks were made on subjects, types, classifications, quantities, and budgets. Three-stage classifications were made to indicate the shared and deviated categories as named or managed. The former are shared core values applied to substantiate cultural events. The latter represent feasible deviations in local identity by the measures of promotion cost, additive construction upon existing infrastructure, settings for tradition, and the enlargement of scale of existing facilities. Follow-up developments were also conducted according to lantern designs awarded by international competitions in 2019 and the reinstallation of festival installations in 2019 and 2020.

The organization of related studies followed the titles of event management to more detailed categories, such as social media, technologies, and examples of Taiwan’s local identities. The economic impact refers to event funds, procurement information, tendering procedure, assistance, and connections with local partnerships and cultural products.

3.1. E-Procurement System

The Government Procurement Act was issued and implemented in 1999, and refers to the acts of international countries, the Government Procurement Agreement of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and Taiwan’s economic environment [6]. In response to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the act was the source of law to be followed by government agencies regarding all kinds of purchasing. Its purpose was to establish an e-procurement system and procedures on a fair and open basis to improve purchasing efficiency and effectiveness. After years of modifications, the law has specified almost all government-sponsored construction, services, and properties. The specifications are applicable to all of administrative actions in the appointment and hiring of engineering projects, financial buy-ins, customization, and leases. Certain restrictions, however, apply: (1) an item or service worth less than USD 3300 can be contracted without public announcement and remain unreportable; and (2) only bid data between 2016 and 2020 were retrieved because of time and effort constraints.

The involved stakeholders are firms or companies, which are natural persons, juridical persons, or institutions or groups by partnership or sole proprietorship. Many construction companies and firms for creative cultural designs were involved.

The annual national festival is governed by the Government Procurement Act and operated according to a government bidding system. Based on records in the government e-procurement system [8], all TLF-related government public tender projects between 2016 and 2020 were retrieved and analyzed. Each year, TLF usually has projects that are announced two years ahead of time to enable sufficient preparation. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 TLF was canceled. Only a few projects were found for 2021, and the date of the last item was on 8 July 2020.

Procurement was important in preparing an event to facilitate real occurrences, to enable fair participation, to support collaboration of parties, to integrate information, to make the best use of budgets, and to create a transparent, open, and public platform. Procurement acted as an instrument for the integration of intangible heritage and tangible management. It was also a catalyst for the social, economic, and environmental issues of culture sustainability. The government acted as the curator of a cultural and commercial event for the efficiency contributed by agencies, a proper division of labor, and the integration of resources. Government teamwork facilitated cooperative measures in general affairs, transportation, traffic control, parking, and even signage reallocation. Business parties or partnerships were created with volunteers, contractors, and department officials within a defined budget, period of time, and available large-scaled open spaces. Its volumetric scale was extended from a temple, city, and an island with a hinterland connected as a network to increase marginal effects.

3.2. Classification of Tender Projects

Procurement is important to plan or manage an event with matching classifications and/or categories suitable for each host city. The corresponding similarities and differences were not consistent. Most of the categories are the same, with new ones added or modified to meet the needs or to promote the identity of the host city each year.

Public tender projects were classified into three groups to relate or clarify project names, subject names, or both:

- Project name: the project names defined under the categories were not consistent. For example, “2020 TLF in Taichung—Professional Commissioned Service of Animal Carnival Lantern Areas” was classified as “Planning or Lantern Layout”. Instead, “2020 TLF Television Commercial AD Agent” was classified as “Media”.

- Subject name: tender projects of the same types were classified under different subjects. For example, mobile toilets were classified as “Services—others” in 2016, and “Sewage, Garbage Disposal, Public Health Planning, and Related Environmental Services” instead in “2017 TLF—Lantern Areas Cleaning and Maintenance Project in Beigang”. The “2016 TLF Video Recording Project” was classified as “Entertainment, Culture, and Sports Service”. In addition, the subject name may not provide a clear indication of category. For example, “2016 TLF—The Operation and Management of Creative Cultural Booths” was classified as “Real Estate Services”, and “2017 TLF—Design and Procurement of Vest and Hat for Volunteers” was classified as “Woven and Tufted Ornaments”.

- Both the subject name and the classification of project “industry” or “profession” were added as a new type of category. In total, 19 categories were classified between 2016 and 2020.

3.3. Case Studies

Case studies of international lantern-related festivals were made to conclude the most significant elements. The surveys and comparisons aimed to determine festival-related descriptions and numerical data made according to the interactions of visitors, organizations, facilities, and spaces (Supplementary Material). The similarities and diversities included numerous factors, such as budget (amount, categories, and expected profits), schedules, urban fabrics (buildings, plazas, or zonings), lantern planning (axis to arrange exhibitions or activities on land, rivers, lakes, or in the air), parties (government departments, international organizations, or local involvers), visitors, facilities (lighting, mechanic, electrical, communications, transportations, and media display), collaborated events (sports, competitions, or culinary tourism), and weather. Not only was the scale indicated by the quantities of installations, visitors, involved parties, days, parking lots, and food booths, but also by the goals achieved by the important measures of international or local exchanges.

4. Results

4.1. Project Numbers and Budgets

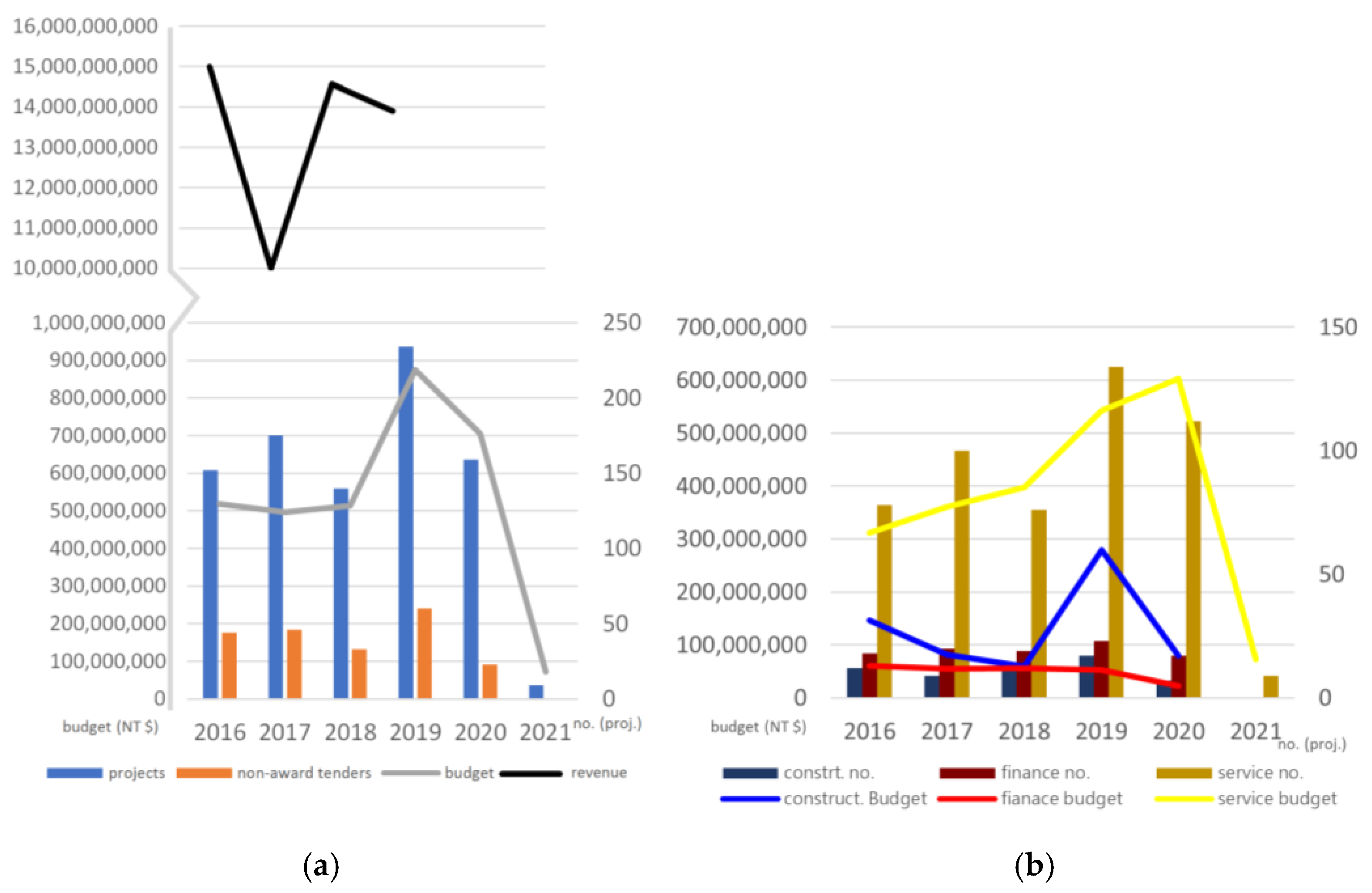

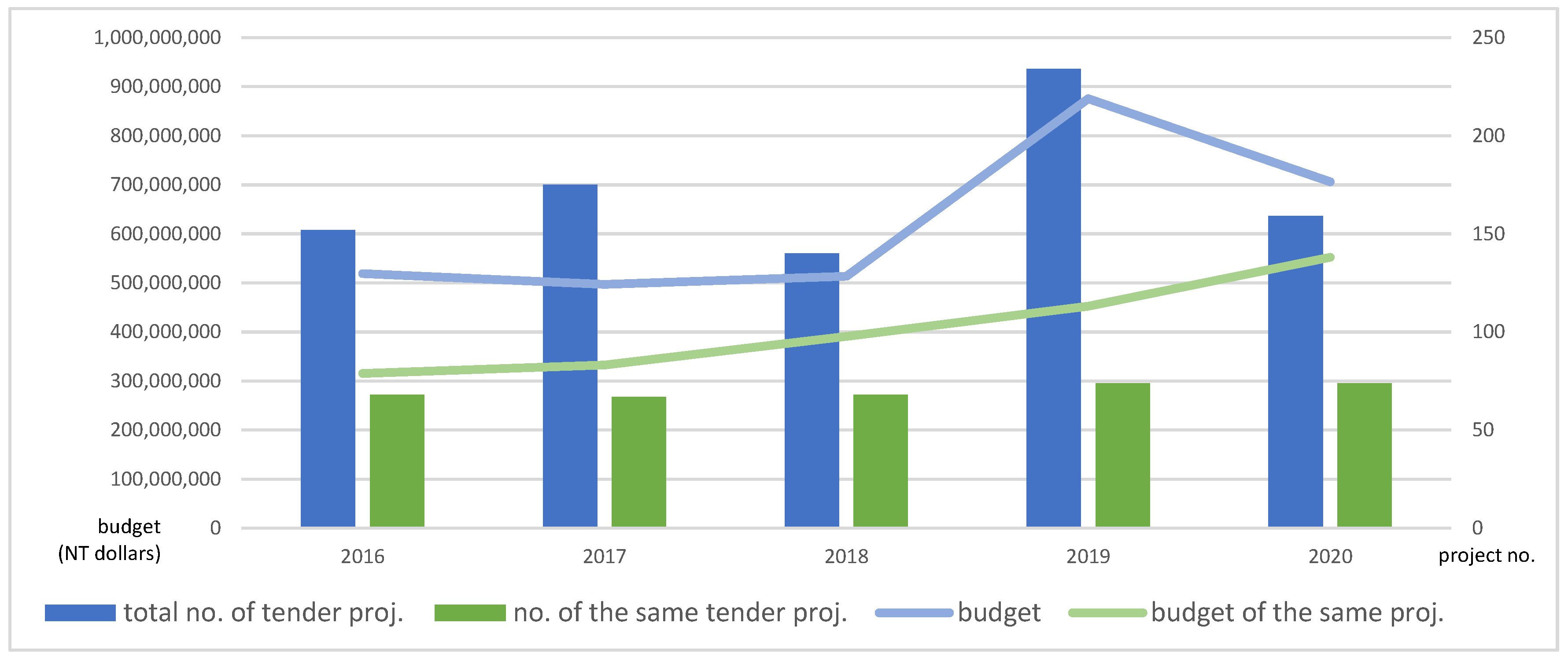

As mentioned in Article 7, Chapter 1, the Government Procurement Act is divided into construction, finance, and services. A project is classified into the one with the highest ratio of budget if two or more types are involved. The project numbers and classification were case-dependent upon the challenges of each host city, location, and thematic identity. The numbers of projects could be different, i.e., up to 100, and led to inconsistent classification, project number, and unconnected graphs in figures. To prevent confusion resulting from the sources of information, the unconnected part of the graph indicates that certain items of procurement were missing that year. In addition, parts of the projects with zero budget amounts for snacks and cultural and creative booths were also not included between 2016 and 2019, since self-financing was applied by contactors with income earned by themselves.

All of the three categories in 2019 were higher than those of other years by budget and the number of procurements. Based on the statistics of the government e-procurement system, 2019 had the highest number of projects of 234, and thus also had the highest budget (Figure 4a). Twenty items in procurement were added to the “services” category. Although the numbers were the highest of the five years, the budget was less than that of 2020 by USD 2 million. The construction budget was increased one to two times more than that of other years (Figure 4b). Although there were 20 more projects in services, the budget was USD 2 million less than that in 2020. Even though it did not attract the most visitors, it did exceed original expectations and was honored as “the most beautiful festival in 31 years” on the internet. The limited 2021 projects are listed only to illustrate the types, numbers, and budgets in the preliminary preparation stage.

Figure 4.

Budgets and project numbers between 2016 and 2021 (a) and a comparison made by construction, finance, and services (b) (USD 1 = NTD 28).

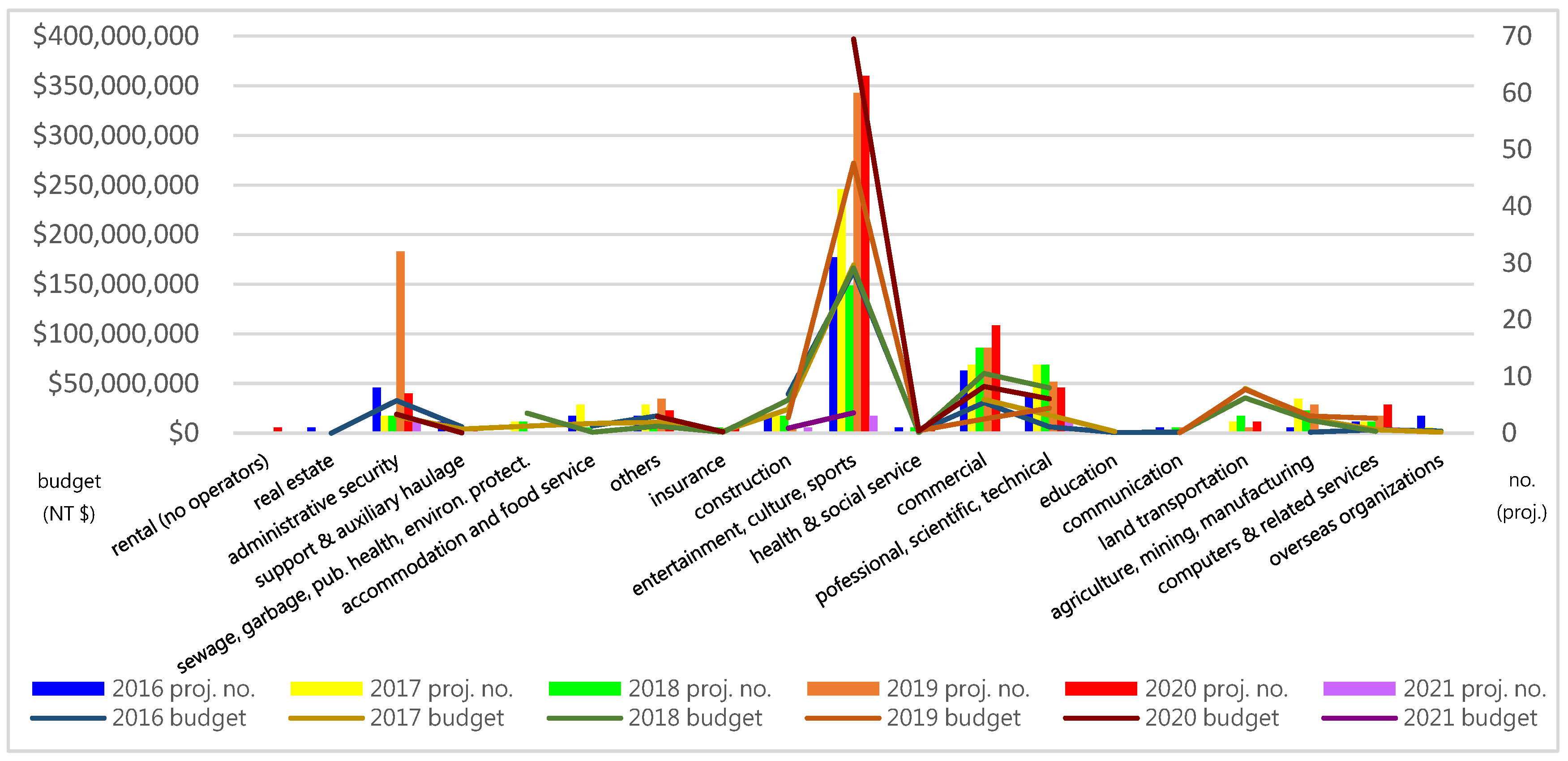

4.1.1. Services

The most dominant lantern design was usually classified in “Services”. “Entertainment, Culture, and Sports Service” constitutes the largest budget (Figure 5), including theme and auxiliary lantern design, handheld lantern design, lantern design in general, lantern car design, documentary filming, performances and shows, and album production. The budget of the “Public Administration and Security Service” was prominent in 2019, including administration, legislation, finance, planning and statistics of economy, and other administration-related services.

Figure 5.

Project numbers and budgets of services between 2016 and 2021.

In 2019, the icon of a tuna fish was applied to the theme of the lantern design in Pingtung County as an expression of a common wish for a full harvest, and it simultaneously promoted a distinct local identity and economy. The lanterns are maintained at the same location after the TLF.

The 2021 Lantern Festival was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a new proposal for reopening or relocating the exhibition to the next host city. For example, the auxiliary lantern, main gate, and characteristic lantern zones were relocated to scenic parks, tourist centers, or Kinmen County as the first Lantern Festival to be held on an outlying island. The theme lantern, which was already made, was prepared to be reinstalled during the Dragon Boat Festival of June in front of the Taiwan High Speed Rail (THSR) station in Hsinchu [64]. The majority of pre-TLF projects are service-related, including master planning, master traffic and transportation planning, promotion and marketing, and the construction of sites and facilities. These items acted as references for the work prepared ahead of the festival.

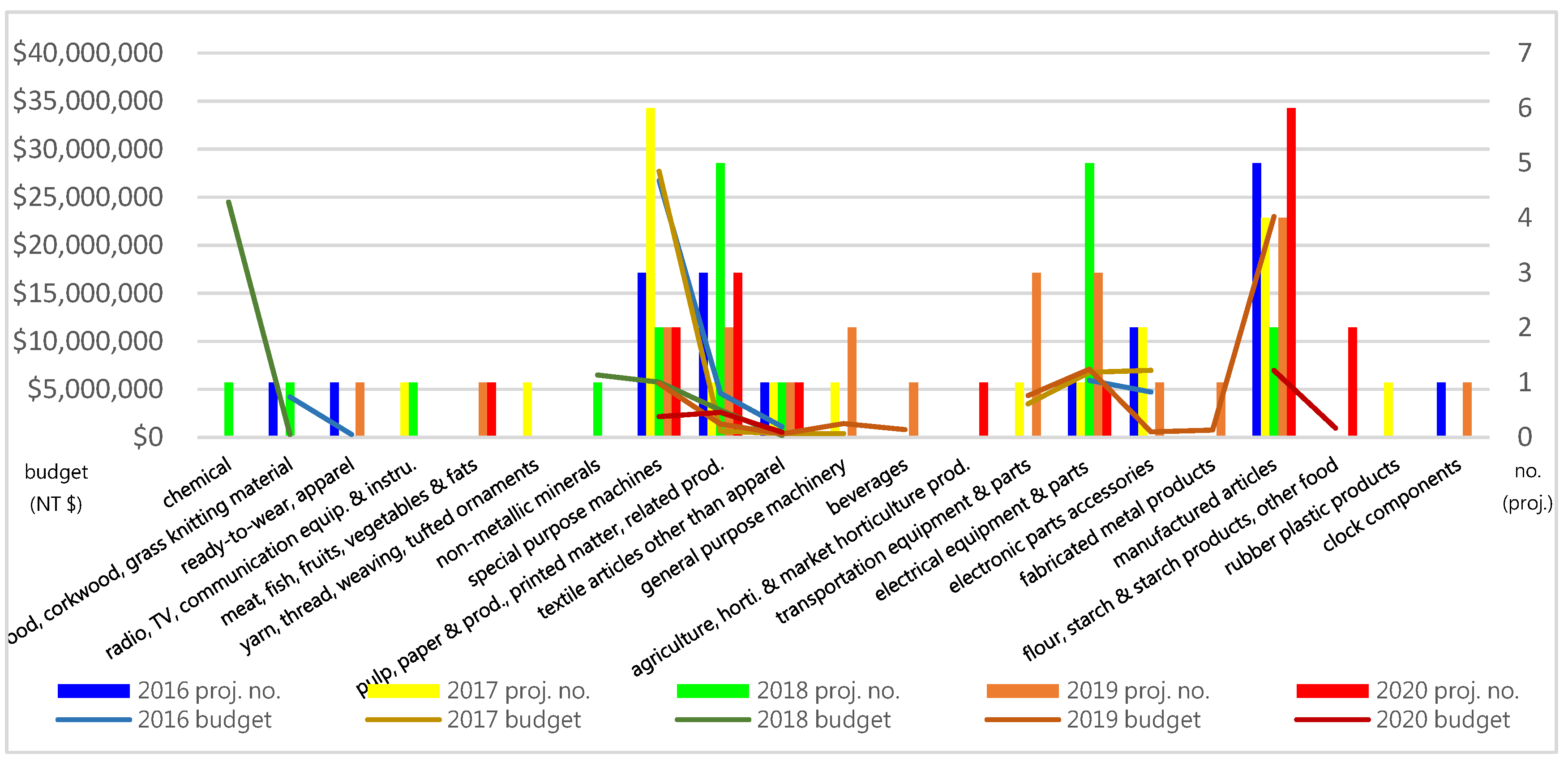

4.1.2. Finance

The following five subjects appeared for four consecutive years: “special-purposed machines and parts”, “pulp, paper and paper products, printed matter and related products”, “non-clothing textile”, “power equipment and parts”, and “manufactured goods” (Figure 6). “Special-purposed machines and parts” in 2017 comprised the largest budget in five years. Major projects were related to the lease of mobile toilets, which constituted 87% of the budget, or USD 8,173,000 in 2018 and USD 679,000 in 2019. Two must-have tender projects were “lantern class” and “souvenirs”, which created an event focus under a limited allocation of budget. The class, which was usually held before the festival, promoted the TLF by teaching and practicing lantern-making skills prior to the final exhibitions of class work during the festival.

Figure 6.

Project numbers and finance budgets between 2016 and 2020.

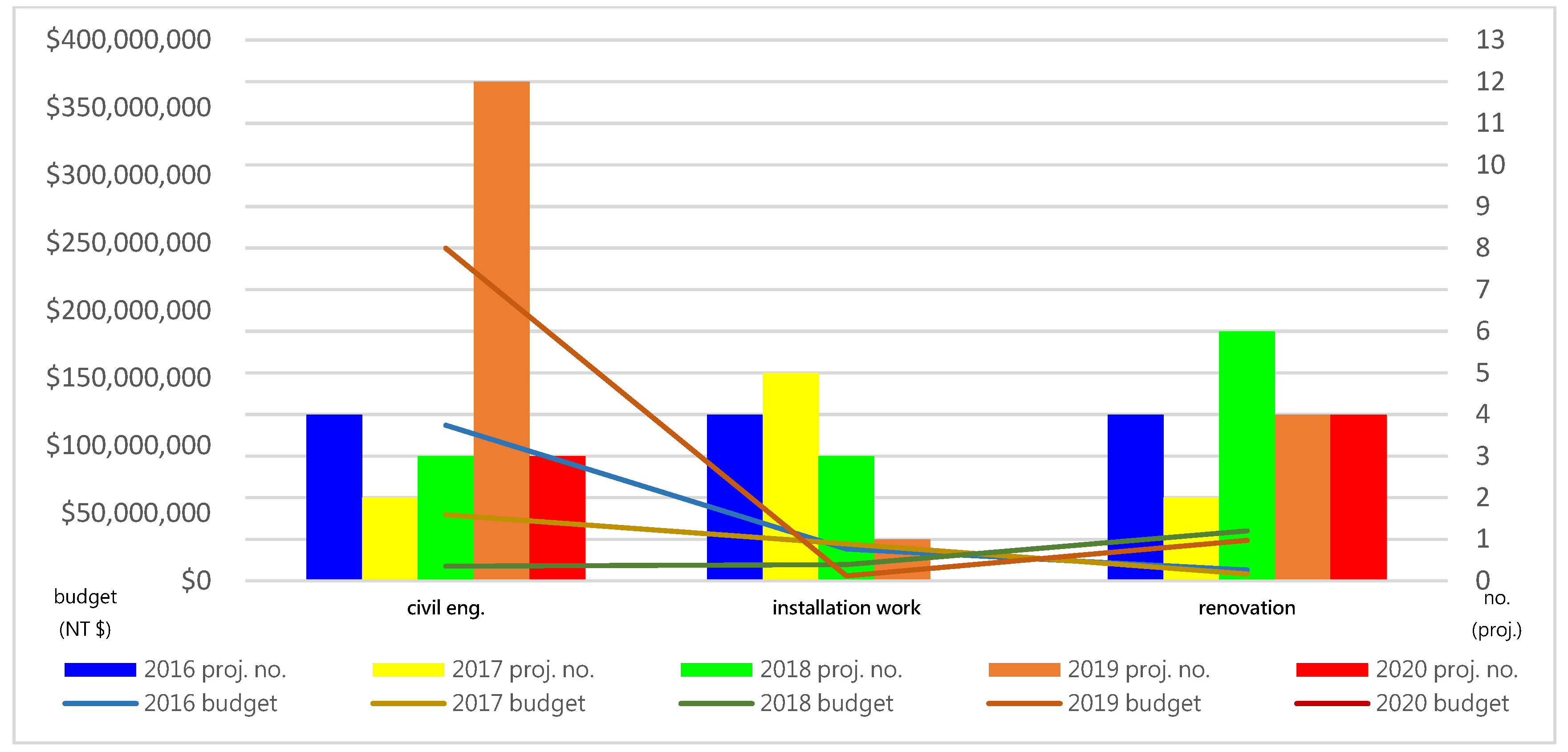

4.1.3. Construction

Although the number of projects was the least, in general, the size of the budget was next to that of services. Over USD 3 million per year was spent between 2016 and 2019, with the majority of the funds allocated for facilities and pavement (Figure 7). The 2019 TLF exceeded the 2016 TLF because temporary parking lots (Table 1) were added next to the site, since the international leisure district was planned without sufficient parking spaces. This is compared to the 2016 TLF site, which was located just in front of the THSR station with easier access island-wide.

Figure 7.

Project numbers and construction budgets between 2016 and 2020.

Table 1.

Traffic facilities by budget.

Renovations were mainly carried out on entrance gateways and light-emitting seats. Although the numbers and allocated amounts of the budget were limited, the facilities were used to promote local characteristics every year by their distinguishing forms and designs.

4.2. Diversities in Tender Projects

The classification led to the findings of the diversities contributed by specific cities and locations. Four city- and location-dependent tender projects were illustrated and followed by an analysis of frequently appearing items:

- Luggage deposits in “miscellaneous”: Taoyuan is the city where the international airport is located. The 2016 festival used this geographical advantage by providing transit passengers with a half-day tour [65]. In addition to promoting the TLF through 12 overseas offices, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs implemented a tender project for 80 large-sized luggage lockers that were issued free of charge to international passengers.

- Disaster-relief drill in “disaster prevention”: one of the 2017 TLF sites in Yunlin County was located near a tourist bridge next to Beigang Creek. A life-saving drill involving rescuing people who may potentially fall into the creek [66] was practiced using equipment purchased from a tender project.

- UAV surveillance and investigation in “information”: a foreign professional UAV team was invited to perform a drone light show at the 2019 TLF. To prevent unexpected interference from private UAV control frequencies, monitoring was conducted at a commanding height and 45 drones were expelled through signal interference [67].

- Mobile toilets: analysis was performed regarding the number of mobile toilets in terms of how the related management was undertaken by local departments to meet the large demands of visitors in such a short period of time. Data were retrieved from government reports, media reports, and official websites. The 2016 TLF was located at an open space in front of a THSR station. Table 2 shows that the 2016 TLF had the largest number of toilets upon the limited public facilities offered in peripheral areas. However, no related tender projects and budgets were found, except for items involved in the cleaning and maintenance of toilets. Although this project classification comprised the major part of the budget, the second stage of classification emphasized case-dependent explanations for unique occurrences. For example, mobile toilets were classified into “service—others” in 2016, “finance—special-purposed machines and parts” in 2017, “finance—special-purposed machines and parts and chemical products” in 2018, and “manufactured goods” in 2019. No tender projects were presented in 2020.

Table 2. Mobile toilets by numbers and budgets.

Table 2. Mobile toilets by numbers and budgets.

4.3. Cultural Exchange and Promotion

Festival sustainability was enabled to share economic opportunities and to exchange culture domestically and internationally. The former included the planning of a large number of service booths to promote culinary tourism involving diversified origins. The latter included continual cultural exchanges in terms of foreign lantern exhibitions, international competitions, design awards, and local post-TLF collections. Some tender projects included budgets for cultural exchange or installation relocation. For example, overseas exchanges were conducted in 2016 with exhibitions of two large lanterns and six small traditional ones in Hong Kong and Kagawaken, Japan. Moreover, lanterns were displayed in a kindergarten and a tea house in Minoshi, Japan, Aomori Nebuta Matsuri, Kagawaken, Japan, Copenhagen, and Malaysia (permanent collection). Awards were granted by A Design Award® and Red Dot Design®. After the 2020 TLF, 21 lanterns were collected by local committees, military units, government departments, service offices of members of parliament, commercial associations, district offices, and city councils. International exchanges were also prepared not only by involving foreign designers, but also through creating an international brand for overseas exhibitions.

5. Discussions

The Cultural Heritage Preservation Act in Taiwan was issued in 1982 [68]. In the act, one of the TLF’s goals was updated to create a brand for cultural sustainability. The TLF represented a sustainability instrument created by a complicated procurement process. The goal of preparing the festival was to combine the occasional enlargement of scale and the promotion of festival value. The results showed that it is a window to introduce an evolving platform under the multidisciplinary practices of finance, services, and construction.

Management experience was delivered in a new era, with the generation of brand and platform to collaborate with novel demands. Findings existed in the exemplification of procurement in an evolved classification, and the clarification of similarities and differences.

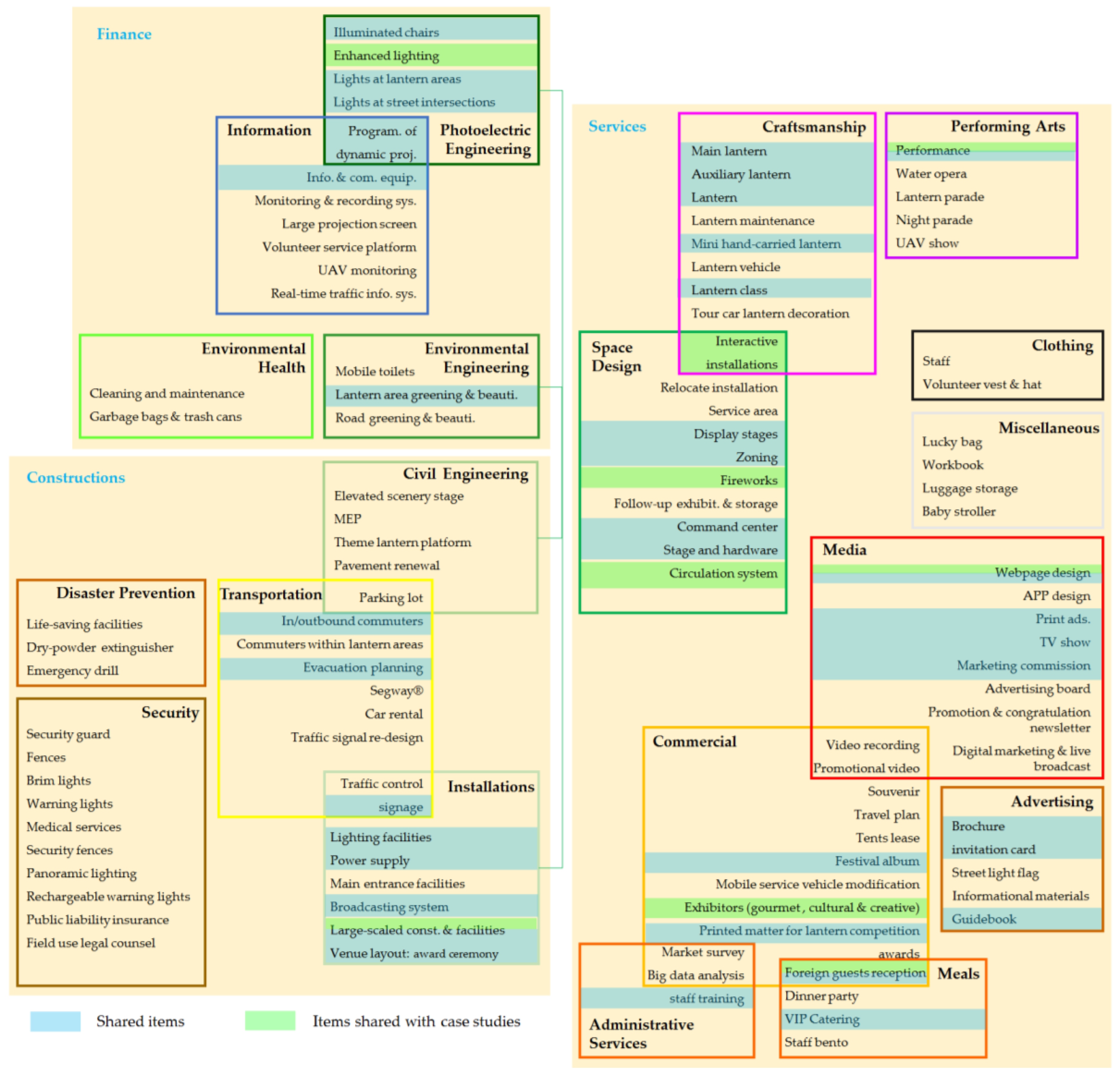

5.1. Evolved Model of Classification for Local Situation and TLF Experience Transfer

Services, finance, and construction contributed to the three main classifications of procurement projects. To clarify corresponding interrelationships, tender projects were classified accordingly in 19 of them between 2016 and 2020 (Figure 8), with items shared (in light blue color) and items included in international case studies (in light green color). The “service” had the most numbers. Assuming the numbers contributed to the level of complexity, the services were important and spread over a long range of the schedule. It contributed to the festivalscape in a direct manner, as the lanterns were included in “space design” and “craftsmanship”. The temporary fabric contributed by parking spaces highlighted the impact of over-mobility. Although environment-related categories may not be shared by all involved cities in “finance”, “construction” contributed to the second-most-diversified categories.

Figure 8.

The diagram of revised classifications by tender project.

The diagram presented a model of procurement and management. The reversed classification included 13 shared categories that contributed to the map of past TLFs. The revision aimed to update the perception of the TLF as a lantern-only event. In addition to the projects included in finance and construction, “lantern” in the “Craftsmanship” of “Services” actually consisted of nine project types, such as main lantern, auxiliary lantern, lantern, mini hand-carried lantern, lantern vehicle, lantern class, tour car lantern decoration, lantern maintenance, and interactive installations.

The Government Procurement Act was issued and implemented in 1999. The procurement, which was defined as one of the processes, seemed to contain no standard classifications of categories. Now, the shared main items demonstrated their importance in transferring the TLF experience to the host city of the subsequent year. The different ones also supported local situations and made each year’s TLF a local-identity-rich event.

5.2. Evolved Measures for Diversities and Shared Similarities

The major challenges of procurement started with the number of visitors exceeding the turning points made in 2001 and 2017, when visitors increased from 5 M to over 10 M in a short period of time. The scale led the preparation to begin two years ahead of time, with 140–234 tender projects and budgets of NTD 496,970,082–875,526,469 between 2016 and 2020, which was an increment of 76%.

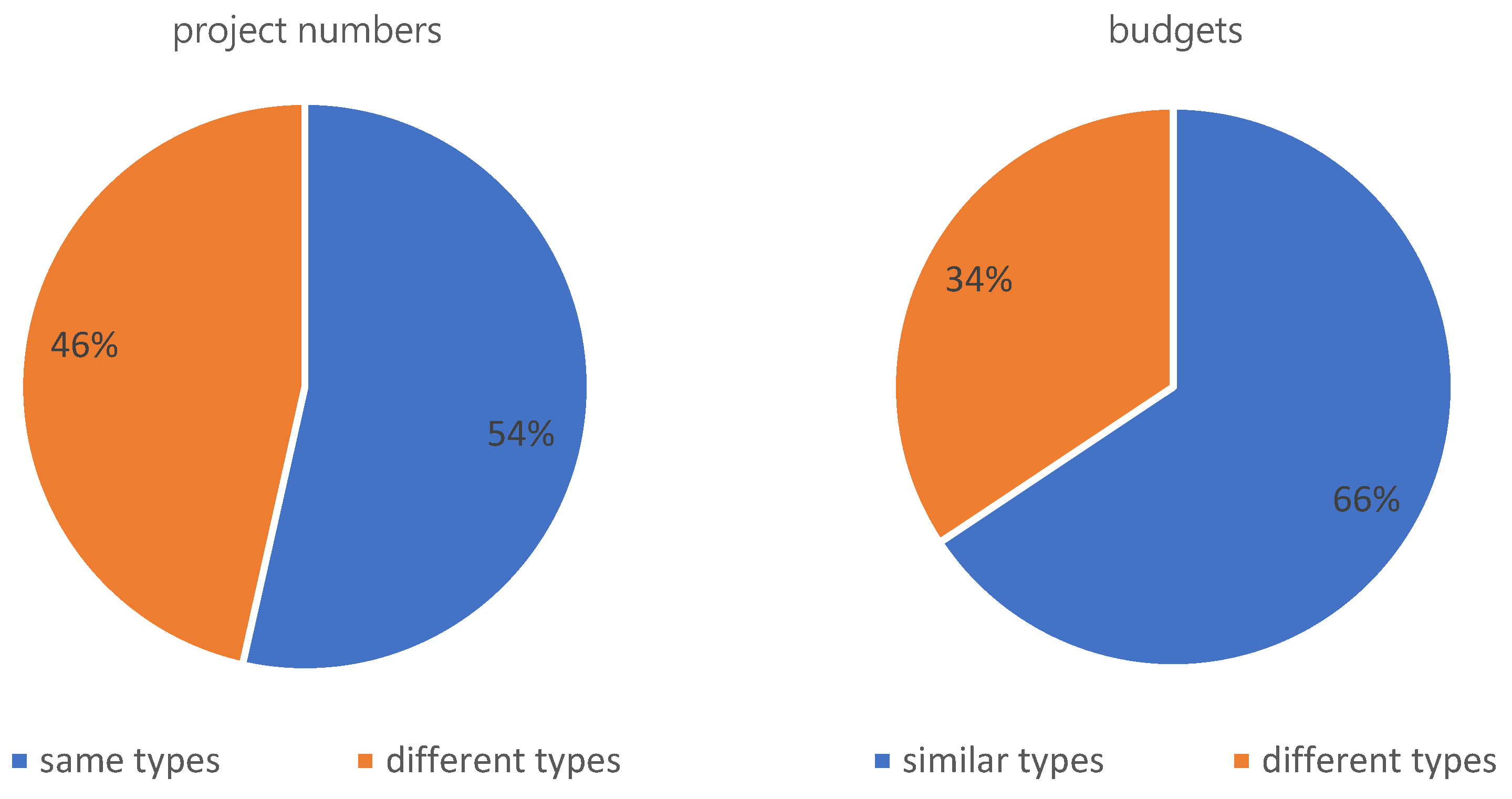

All the projects of the same types, which were cross-compared with annual projects and budgets, comprised approximately half of the project numbers and more than half of the budgets (Figure 9). The unshared project items varied markedly. In contrast, the 2019 TLF had two thirds of the different projects related to facilities, construction, and safety equipment. The numbers of lanterns were also greater, since Pingtung County exhibited characteristic designs for each of the 33 villages and towns. In contrast to the fact that the number of similar types increased gradually, the amount of the budget increased 75% from NTD 315,409,605 in 2016 to NTD 552,218,487 in 2020. The projects demonstrated their importance in transferring the TLF experience to the host city of the subsequent year.

Figure 9.

Number and budgets of similar tender projects.

The classification leads to the finding of 36 shared repetitive project types in 13 categories, including photoelectric engineering, information, transportation, installations, craftsmanship, space design, performing arts, media, commercial, administration services, meals, and advertising. The classification led to the four findings of diversities contributed by specific cities and locations in terms of mobile toilets, luggage deposits, disaster relief drills, and UAV surveillance and investigation. The similarities and differences in procurement made each year’s TLF a local-identity-rich event.

Certain shared levels of similarities were identified in approximately 54% (351 items) of all tender items (654 items) and 66% of the budget (Figure 10). With the repetitive practices of the TLF, only about half of the tender items remain similar. However, major differences in each year’s budget map, which were not necessary quantity-related, also presented a success with enhanced local heritage in the reactivated urban fabrics of the host cities.

Figure 10.

Percentage of numbers and budgets by similar and different tender projects between 2016 and 2020.

5.3. Evolved Instrumentation for Traditions

Procurement enabled security and safety practices, technological advances, and situated education and participation. The concern of security and safety has been raised in tourism. Exemplifications were found when UAVs and drills were planned and deployed to solve potential security concerns through the monitoring and real-time information collection of any irregular on-site occurrences. Technological advances were not only implemented for the evolved design of the main theme lantern and small hand-held lanterns, but also for the UAV shows with different combinations of dynamic patterns in the air. However, these advances came with a major negative consequence: multiple UAV crashes in a show caused by interference from unknown bandwidths. The application of technology created new concerns and demands for auxiliary facilities and security procedures.

Lantern making was a highly successful activity, in which traditional crafts could be inherited with a close connection between cultural heritage and entertainment. Situated education and participation also contribute to the development of professional lantern makers with skills and knowledge offered in lantern-skill classrooms, camps, studios, competitions, and presentations of the works of skilled experts.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the integration of procurement and cultural event. The TLF committee of the host city was assigned a new role as event manager with enlarged scope, resources, and correspondence to a national tourism white paper. Procurements were conducted with matching categories. The domains, phases, and processes were reflected in the procurement categories and items, with functional dependence elaborated to facilitate the place dependence of the host cities with services, finance, and construction. The festival can be defined by the items listed in the procurements.

The TLF is an event product renowned as a brand for the purpose of cultural preservation and reactivation. TLFs contribute to the tradition and construction of lanterns and supporting facilities. The annual enlargement of the scale of the TLF encountered the enriched interpretation of tradition. The place identity of the host city had been represented in the procurements and simultaneously promoted the brand of the TLF.

The revised classification of tender projects contributed to an empirical model, which came from the analysis of the procurement records. It also followed the original government classification of finance, services, and construction. The model was proofed with dynamic characteristics, since the analyzed results presented certain shared levels of similarities that were identified. The 36 shared main items, which were cross-compared with annual projects and budgets, comprised approximately 54% of all 654 tender items and 66% of the budget. This also explained how an important festival could be featured in such diversity and how most of the projects or items could still be shared among the host cities. This was considered as the cost of adaption to local conditions or identities on an island only 496 km long and 140 km wide.

Local hierarchies were combined into a higher hierarchy of identity through the procurement mechanism. The TLF is redefined by self-evolvement. It represents a unique combination of local and international festivals, under which parallel festivals are held at the same time in other cities or by different organizations. Compared to a fair, a festival usually has a theme [69]. The cultural event represents an important practice for the management of heterogeneous data from traditions and budgets, to the procured items, whose hosting rights are implemented by different cities. It creates a unique level of hierarchy in the management of each city’s identity and place dependence on great brand loyalty, with a successful adaption of procurements. Since team identification leads to event attachment [70], the attachment was transferred to the brand of the TLF in new hosting cities island-wide.

The festival continually evolves with participating parties to form a window of culture, technology, and government procurement history under different scales. It also creates a platform for multidisciplinary practices under various levels of classification. Future studies would explore other local events with geography-specific classifications for detailed and evolving culture-based assessments.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14095147/s1, Table S1: Comparisons of large-scaled lantern-related festivals. References [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] are citied in supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.-J.S.; methodology, N.-J.S.; 3D validation, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; formal analysis, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; investigation, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; resources, N.-J.S.; data curation, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; writing—review and editing, N.-J.S.; visualization, N.-J.S. and T.-Y.C.; supervision, N.-J.S.; project administration, N.-J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. 20th Anniversary Review of Taiwan Lantern Festival; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. Tourism White Paper; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2001; Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/Handlers/FileHandler.ashx?fid=b82f47a5-8490-4cd3-a1d2-189682c9879b&type=4&no=1 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. Taiwan Tourism—An Impressive Journey 1960–2020; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020; Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/TaiwanTourism_60TH/TaiwanTourism.html (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. Tourism 2020; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018; Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/Handlers/FileHandler.ashx?fid=8f189a29-8efa-453f-a0d5-279bb37e121a&type=4&no=1 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. Taiwan Tourism 2030; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020; Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/Handlers/FileHandler.ashx?fid=3ef70448-05a4-49a0-b8ce-f7702ee65e4f&type=4&no=1 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Executive Yuan. Government Procurement Act; 2019. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=A0030057 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Commission of Public Construction Commission (PCC). Government e-Procurement System; Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019. Available online: http://web.pcc.gov.tw/tps/pss/tender.do?method=goNews (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Felsenstein, D.; Fleischer, A. Local Festivals and Tourism Promotion: The Role of Public Assistance and Visitor Expenditure. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Bureau Taiwan. Annual Statistical Report on Tourism—Monthly Tourist Report of Domestic Major Tourism and Recreational Areas; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018; Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/FileUploadCategoryListC003330.aspx?Pindex=1&CategoryID=2638da16-f46c-429c-81f9-3687523da8eb&appname=FileUploadCategoryListC003330 (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- United Nations Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Conventions and Declarations Information Retrieval System. Available online: https://www.un.org/zh/documents/treaty/files/whc.shtml (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Goldblatt, J. Special Events: Creating and Sustaining a New World for Celebration, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event tourism definition, evolution and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event Tourism Concepts, International Case Studies and Research; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Putnam Valley, NH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Event Studies: Theory, Research and Policy for Planned Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malchrowicz-Mo’sko, E.; Poczta, J. A small-scale event and a big impact—Is this relationship possible in the world of sport? The meaning of heritage sporting events for sustainable development of tourism—Experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.S. How event awareness, event quality and event image creates visitor revisit intention? A lesson from car free day event. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Event Management Body of Knowledge (EMBOK). EMBOK Model. Available online: https://www.embok.org/index.php/processes-page (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Kose, H.; Argan, M.T.; Argan, M. Special event management and event marketing: A case study of TKBL all star 2011 in Turkey. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2011, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, K.F. Event management research: The focus today and in the future. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naehyun, P.; Lee, S.; Daniels, M.J. Wedding professionals use of social media. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J. Events as proenvironmental learning spaces. Event Manag. 2014, 18, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.; Yeoman, I.; Smith, K.; McMahon-Beattie, U. Technology, society and visioning the future of music festivals. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainhofer, T.C. Mapping of Collaboration Models among Film Festivals—A Qualitative Analysis to Identify and Assess Collaboration Models in the Context of the Multiple Functions and Objectives of Film Festivals, Report Commissioned by the European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://ced-slovenia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Report_MappingofCollaborationModelsamongFilmFestivals-1.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Lee, T.-S.; Huh, C.L.; Yeh, H.-M.; Tsaur, W.-G. Effectiveness of a communication model in city branding using events: The case of the Taiwan Lantern festival. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2016, 7, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Chang, C.C. Study on place marketing strategy of festival tourism activity. MingDao J. Gen. Educ. 2009, 7, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Park, E.O.; Kwon, J.; Chae, B.K. 30 years of contemporary hospitality management: Uncovering the bibliometrics and topical trends. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2641–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Ali-Knight, J. Aspirations and progression of event management graduates: A study of career development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 30, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowdin, G. Informing content and developing a benchmark for events management education. In LINK 20: Events Management, Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Network; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2007; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sibson, R. Career choice perceptions of undergraduate event, sport and recreation students: An Australian case study. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2011, 10, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, J.R.; Bowdin, G.; O’Toole, W.; Nelson, K.B. Towards an international event management body of knowledge (EMBOK). Event Manag. 2006, 9, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, R. Two paths diverge in a field: The increasing professionalism of festival and events management. In LINK 20: Events Management, Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Network; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2007; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.; Barron, P.; Solnet, D. Innovative approaches to event management education in career development: A study of student experiences. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2008, 7, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event studies: Definition, scope and development. LINK 20: Events Management, Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Network; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2007; pp. 2–3.

- Business Visits and Event Partnership (BVEP). Events are Great Britain; BEVP: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser, D.; Vlachos, P. Almost like being there? A conceptualisation of live-streaming theatre. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjønndal, A. Identifying motives for engagement in major sport events: The case of the 2017 Barents Summer Games. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, M.B.; Künzi, A.; Lehmann Friedli, T.; Müller, H. Event performance index: A holistic valuation tool. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Navarro, C. Events and the blue economy: Sailing events as alternative pathways for tourism futures—The case of Malta. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, C.; Schofield, P.; Berridge, G. Agricultural shows: Visitor motivation, experience and behavioural intention. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J.; Thomas, L.Y.; Fenich, G.G. Event management research over the past 12 years: What are the current trends in research methods, data collection, data analysis procedures, and event types? J. Conv. Event Tour. 2018, 19, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Ho, C.-I. Tourism information technology research trends: 1990–2016. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.; Westcott, M. (Eds.) Introduction to Tourism and Hospitality in B.C., 2nd ed.; BCcampus: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://opentextbc.ca/introtourism2e/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- South Australian Tourism Commision. Events South Australia—Leisure Events Bid Fund. Available online: https://tourism.sa.gov.au/events/event-funding (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Prince Edward Island. Proposals Sought for Large-Scale Spring Tourism Event. 22 June 2018. Available online: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/proposals-sought-large-scale-spring-tourism-event (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Government of Jamaica. Design and Implementation of an Entertainment Plan for the Artisan Village in Falmouth for TEF, Tourism Enhancement Fund. 15 February 2021. Available online: https://tef.gov.jm/procuremnt/design-and-implementation-of-an-entertainment-plan-for-the-artisan-village-in-falmouth-for-tef/ (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Tehri Special Area Tourism Development Authority (TADA). Invitation for Submission of Bids for Selection of Event Manager for Tehri Lake Festival 2020 at Koti Colony. Tehri Lake Festival Tender 2020. January 2020. Available online: https://uttarakhandtourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-01/tehri-lake-festival-2020-2412020.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Ashley, C.; Haysom, G.; Poultney, C.; McNab, D.; Harris, A. Boosting Procurement from Local Businesses, September 2005, Overseas Development Institute Business Linkages in Tourism. Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/2255.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). FITUR 2021—International Tourism Fair in Madrid. Available online: https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/database/j-messe/tradefair/detail/110021 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Hawaii Tourism Authority. Request for Proposals. Available online: https://www.hawaiitourismauthority.org/rfps/ (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- The Department of Tourism (DOT)—Republic of the Philippine. Open Project for Bidding, Project Procurement Management Plan (PPMP), Open Project for Bidding. Available online: http://www.tourism.gov.ph/DOTOpenProjectsforBidding.aspx (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.J. Political economy of tourism: Trust in government actors, political support, and their determinants. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-R.; Lin, W.-R.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-P. Sustainability indicators for festival tourism: A multi-stakeholder perspective. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Application of marketing in cultural organizations: The case of the Polish Cultural and Educational Union in the Czech Republic. Cult. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2017, 1, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, B.M. Marketing for Cultural Organisations: New Strategies for Attracting Audiences to Classical Music, Dance, Museums, Theatre & Opera; Thomson Learning: Cork, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leenders, M.A. The relative importance of the brand of music festivals: A customer equity perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2010, 18, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, Ł.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z. Sustainable Consumer Behaviour in the Market of Cultural Services in Central European Countries: The Example of Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Thrifty, green or frugal: Reflections on sustainable consumption in a changing economic climate. Geoforum 2011, 42, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy-beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.; Alevizou, P.J.; Young, C.W.; Hwang, K. Individual strategies for sustainable consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Cultural Capital. J. Econ. 1999, 22, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, J.; McLoughlin, J.; Sodagar, B. Heritage Impact 2005; Archaeolingua: Budapest, Hungary, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Z.; Kennell, J. The Role of Sustainable Events in the Management of Historic Buildings. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Bureau, Taiwan. 2021 Taiwan Lantern Festival. Available online: https://theme.taiwan.net.tw/2021taiwanlantern/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Hsieh, W.S. Luggage Storage Service Provided at the Exists of THSR Station. Liberty Times Net. 19 February 2016. Available online: https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/society/breakingnews/1607455 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Press Office—Public Relations Division. Life-saving Maneuver Offered by Fire Department of Yunlin Country on 24th for 2017 Taiwan Lantern Festival, Yunlin Country. 24 June 2016. Available online: https://www.yunlin.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=1244&s=216599 (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Chen, T.T.; Qiu, J.P.; Chang, M.S. Snipers in Taiwan Lantern Festival! 45 UAVS Were Repelled. CTS News. 25 February 2019. Available online: https://news.cts.com.tw/cts/local/201902/201902251952997.html (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Bureau of Cultural Heritage. Cultural Heritage Preservation Act, Article 1 Chapter 1, Ministry of Culture (MOC). Available online: https://www.boch.gov.tw/information_160_73735.html (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism—Government of India. Evaluation of the Plan Scheme—Product Infrastructure Development at Destinations and Circuits (PIDDC). January 2013. Available online: https://tourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-04/PDF%20PIDDC%20Final%20report.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Prayag, G.; Mills, H.; Lee, C.; Soscia, I. Team identification, discrete emotions, satisfaction, and event attachment: A social identity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aomori Nebuta Festival Executive Committee. Nebuta Festival. Available online: http://www.nebuta.jp/ (accessed on 23 February 2020).

- World Journal. Hello Panda Festival. Available online: http://panda.worldjournal.com/ (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Hellopandafest. Hello Panda Festival. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/pg/hellopandafest/about/?ref=page_internal (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Visit Philadelphia. Philadelphia Chinese Lantern Festival. Available online: https://www.visitphilly.com/things-to-do/events/philadelphia-chinese-lantern-festival-at-franklin-square/ (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Xi’an Daily. Here Comes 2019 Qinhuai Lantern Festival—Co-organized by Xi’an and Nanjing for the First Time! Nanjing Daily. 10 January 2019. Available online: https://kknews.cc/zh-hk/culture/mjn9np6.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- ChiLong Technology. The Originality of Nanjing Qinhuai Lantern Festival. ChiLong Technology. Available online: http://www.caidenggongsi.com/xinwen/denghui/715.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Ho, L.J. Jiangsu: Illuminations Light up Cross-Strait Relations. Xinhuanet. 15 February 2019. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/2019-02/15/c_1124121391.htm (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Chen, X.G. Human Body Guardrail in 400000 People. Lens Story. KKnews. 20 February 2019. Available online: https://kknews.cc/zh-my/military/q45mg6g.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Wang, Y. Lighting Ceremony on 17th at Xi’an City Wall New Year Lantern Festival with Main Lantern of Mouse 18 m High and Color Changed in 360 Degrees. Available online: http://www.cnwest.com/tszx/a/2020/01/10/18359866.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Lee, X.X. Chinese year in Xi’an–the Activation of a Series of Cultural Tourism. In Shaanxi Provincial Department of culture and Tourism; 3 January 2020. Available online: https://www.mct.gov.cn/gtb/index.jsp?url=https://www.mct.gov.cn/whzx/qgwhxxlb/sx_7740/202001/t20200103_850078.htm (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Lee, X.J. Stunning the World with Zigong Color Lanterns at Xi’an City Wall on the Day before New Year’s Eve. Guangming Daily. 10 February 2018. Available online: http://www.wenming.cn/wmzh_pd/sj/sjtp/201802/t20180226_4599127.shtml (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Wang, Y. Planning and Conservation in Historic Chinese Cities: The Case of Xi’an. Town Plan. Rev. 2000, 71, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q. 2019 Guide to Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival. 25 January 2019. Available online: http://heb.bendibao.com/tour/2019125/51270.shtm (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Qidou Tourism Net. Pilgrimage of the World Largest Ice and Snow Festival–Colorful Debut of the Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival. ETtoday. 21 November 2018. Available online: https://travel.ettoday.net/article/1311337.htm (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Dong, Y.Z. The 35th Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival will be held with more than a hundred events. Heilongjiang News. 27 December 2019. Available online: http://m.xinhuanet.com/hlj/2018-12/27/c_137701085.htm (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Chen, W. Popularity Comparable to New Year’s Eve! The Largest Celebration in the Southern Hemisphere “Vivid Sydney” Is Coming soon with Three Themes and Ten Must-Visit Regions. ezTravel. 23 May 2019. Available online: https://www.vogue.com.tw/culture/content-47145 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Schneider, E. Vivid Sydney is about to Having the World Largest Lights and Music Stage Ideas. Australia. Available online: https://www.australia.com/zh-hk/events/arts-culture-and-music/vivid-sydney.html (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Vivid Sydney. Sustainability. Destination New South Wales, New South Wales Government. Available online: https://www.vividsydney.com (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Vivid Sydney. Vivid Light Walk Backgrounder Nightly from 6pm–11pm 27 May–18 June 2016. Available online: https://www.vividsydney.com/sites/default/files/20150317-Vivid-Sydney-Light-Walk-2016-Media-Backgrounder_0.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Parmenter, G. The City Branding of Sydney. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230294790_27 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Festival of Lights. Berlin, Videos. Available online: https://festival-of-lights.de/en/videos/ (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Festival of Lights. Berlin, One of the Most Famous and Popular Festivals in the World. Available online: https://festival-of-lights.de/en/ (accessed on 25 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).