Abstract

Designing a digital marketing strategy that stimulates consumer engagement is vital and challenging for digital marketers. Despite previous research on this topic, little is known about the unpaid (organic) strategies of digital marketing and how they attract web traffic through consumer engagement. Based on the stimuli–organism–response model, this study examined the effects of three organic marketing practices related to electronic commerce shopping platforms, namely, search engine optimization, social media posts, and user-generated content, on consumer engagement. Covariance-based structural equation modeling was utilized to analyze 464 responses from followers of five electronic commerce firms’ Facebook fan pages. Based on the stimuli–organism–response paradigm, we found that organic marketing practices positively impact consumers’ behavioral engagement; however, consumers’ psychological engagement partially mediates these impacts. Further, consumers’ attention to social comparison of consumption dampens the positive effect of search engine optimization and psychological engagement on consumers’ behavioral engagement. The findings of this paper improve our understanding of the roles played by organic digital marketing practices in attracting consumer engagement and provide guidelines for digital marketers on how to utilize unpaid marketing strategies to attract authentic consumer engagement. This study presents a new framework in measuring the digital marketing strategies available to electronic commerce firms exploring unpaid marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement in internet technology has given rise to innovative opportunities to electronic commerce (e-commerce) and digital marketing [1]. Modern marketing strategies have adapted to this new trend of digital marketing, and businesses are building a solid web presence through digital marketing. Digital marketing focuses on consumers’ needs through effective communication strategies. Organic marketing is the most effective digital marketing strategy for building an authentic consumer connection [2]. It is a “natural” way of attracting consumers to products and services over time rather than “artificial”, or paid, marketing. Organic marketing drives traffic, increases the conversion rate, and generates leads. The investment of time in maintaining their social media accounts, revision and reinvention of brands’ website interface, and improving their search engine optimization (SEO) defines organic marketing [3,4]. User-generated video and image contents, optimized websites, blog posts, and social media accounts are nearly free marketing resources that are essential and interactive [5].

Marketing trends are shifting from passive advertisement to active engagement with social networking sites [6]. This shift has called on several researchers to investigate marketing assets that enhance behavioral engagement [7,8]. However, studies have not investigated the organic aspect of digital marketing, where natural and value-based marketing practices drive website traffic and increase firms’ conversion rates [8,9]. The reliance on consumer engagement in organic marketing places it among the unique components of digital marketing. Opposite to organic marketing, an “artificial” (paid) marketing strategy—for instance, pay-per-click, celebrity/influencer marketing, and brand ambassadors- require direct expenditure to affect consumer engagement [10]. Additionally, previous research on consumer engagement with marketing strategies has focused more on consumers’ purchase behavior [11,12].

This study, therefore, investigates the primary organic marketing practices available to firms in the context of e-commerce. It further identifies the impact of organic marketing on consumer engagement beyond purchase intention by examining consumers’ psychological and behavioral engagement attitudes. Psychological engagement is the firm-related cognitive and emotional state of mind of consumers, and behavioral engagement is the observable consumer participation in the e-commerce firms’ social media fan pages. Finally, this study introduces consumers’ attention to social comparison of consumption (ATSCC) choices as a moderating effect on the relationships between organic marketing and consumer engagement. This study adopts the stimuli–organism–response (S-O-R) paradigm to share insights on organic marketing in e-commerce. It investigates the varied impacts of organic marketing on consumers’ psychological and behavioral engagement and the buffering effect of ATSCC on the relationships between organic marketing and behavioral engagement. The study introduces a new framework to measure the impacts of digital marketing strategies on consumer engagement. It further presents knowledge on how consumers’ sensitivity to avoiding faux pas relates to the strength of their engagement.

The rest of the study is organized as follows. The next section outlines the literature review and the theoretical development of the hypothesized relationships. Section 3 details the methodology of the study. In Section 4, the analysis and results of the theoretical model are presented. Finally, Section 5 illustrates a detailed discussion of the outcome, theoretical and practical implications of the findings, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Engagement

With social networking sites in mind, we developed a framework based on the classical concept of consumer engagement [13,14]. The underlying idea of the framework is that consumers will demonstrate engagement behaviors if they interact with organic marketing practices. Previous researchers have adopted several frameworks to evaluate the concept of consumer engagement [15,16]. Pansari and Kumar [16] developed a framework that focused on customer engagement, demonstrating how engagement is gained via emotions and satisfaction— and linking the direct and indirect engagement contributions. Demangeot and Broderick [15] developed a framework that focused on consumer engagement with a website characterized by relational and communication knowledge. Researchers in the service community have widely investigated the consumer engagement concept [13,17]. The investigations by these researchers indicate that consumer engagement goes beyond psychological, unobservable attitudes and transactions. It includes firm-focused consumers’ observable behavioral manifestations, beyond purchase, as a result of motivational factors [13].

Applying the concept to social networking sites (SNS), studies have identified: how consumer engagement shapes the dynamics of virtual brand communities [18]; system support, community value, freedom of expression, reward, and recognition as antecedents of consumer engagement in online brand communities [19]; and extraversion, openness to experience and altruism as personality traits that positively influence consumer engagement in online brand communities [20]. Consumer engagement literature has evolved with the modernization of new technologies and tools of Web 2.0 [21]. According to previous studies, explicit interpretations of consumer engagement is context-based [22,23]. The consumer engagement concept and the relationship marketing theory are closely linked with the assertion that consumer behaviors are affected by the experiences perceived in an increasingly complex environment [24].

In the context of e-commerce, this study defines consumer engagement as the e-commerce firm-related unobservable (Psychological) and observable (behavioral) engagement attitudes demonstrated by consumers on social media, triggered by the perceived interaction experience with organic marketing practices. Similar to the definition of Brodie et al. [22], psychological engagement in the current study represents the firm-related cognitive and emotional state of mind of consumers. It is characterized by vigor, absorption, and dedication. Vigor refers to a consumer’s energy level and mental resilience while interacting with the firm. Absorption is when a consumer has total concentration and happiness/sadness and is deeply engrossed in the interaction with the firm. Finally, dedication is the sense of significance, inspiration, pride, and enthusiasm a consumer attaches to the interactions with a firm [25]. Similar to the definition by Brodie et al. [26], behavioral engagement in this study represents the observable consumer participation in the e-commerce firms’ social media fan pages. This visible participation is manifested through electronic word of mouth (eWOM); commenting on, liking, and sharing firm-related social media posts; and loyalty. In general, the definitions in this study emulate the stance of Bowden [27], Brodie et al. [22], and Doorn et al. [13] that consumer engagement is a process. In particular, this study examines consumer engagement as an attitudinal process that begins with consumers’ psychological engagement with an e-commerce firm, which triggers firm-related behavioral engagement activities on social media.

2.2. S-O-R Paradigm

In the field of psychology, the S-O-R paradigm evaluates individuals’ cognitive states through three distinct but connected actors, namely, environmental stimuli (S), innate cognitive state (O), and behavioral response (R) [28]. The paradigm delineates how the organism mediates the relationship between stimuli and response. The organism refers to the cognitive and affective mediating mechanisms that transmit external environmental stimuli into behavioral responses. The S-O-R paradigm applies to several consumer behavior studies [28,29]. Javadi et al. [30] employed the S-O-R model in the social commerce context to examine factors affecting consumers’ behavioral intentions on social networks.

Accordingly, consumers’ psychological engagement (O) manifested through vigor, absorption, and dedication attitudes that are triggered by firms’ organic marketing practices (S) result in observable behavioral engagement activities (R). This study is interested in developing a framework to explain the formation of consumer engagement with e-commerce firms on SNS induced by consumers’ interactive experience with the firms’ organic marketing practices. We propose an extended S-O-R model to examine the developed framework. The S-O-R model is extended by including ATSCC as a moderating variable affecting the intensity of consumers’ behavioral engagement (R).

2.3. Organic Marketing

Online marketing enables a broader web presence and assists in wider consumer reach compared to traditional technologies like messaging and telemarketing [31]. Online marketers enrich, distribute, and promote content through e-commerce websites and SNS to increase their presence and maximize market size [32]. E-commerce websites and SNS have become the ideal stages to promote firms and brands and build a long-lasting connection with the target consumers. However, online marketers contemplate whether it is worthwhile to spend on the strategies they adopt (paid marketing) or adopt an approach with almost no cost involved (organic marketing).

There are two ways a consumer can discover a firm using internet search mediums: natural search results (organic marketing) and paid marketing [33]. Adopting paid marketing practices benefits firms in terms of unlimited consumer targets. However, the strategies do not effectively reach new consumers [34,35].

Organic marketing subsumes practices that do not involve the direct monetary expenditure on advertisements [36]. A firm attains an organic reach when consumers realize its presence through unpaid web-based distribution. Unlike paid marketing, organic marketing practices develop and strengthen consumer relationships through interactions [36]. Scant research has considered the value of organic marketing practices and their contributions [37]. Organic marketing is motivated most intensely by small or nonexistent expenditure involved and the establishment of a long-lasting interactive relationship between firms and consumers. It relies on SEO, social media posts, and UGC to establish an interactive relationship with existing and potential consumers [10]. Accordingly, this study examines the SEO of e-commerce platforms, social media posts on the e-commerce firm’s fan page, and firm-related UGC on Facebook as organic marketing practices. These practices represent the environmental stimuli that potentially attract engagement behaviors on social media.

2.3.1. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

SEO is a mechanism that enables users to ascertain the most valuable results from their online search. Search engines are vital mechanisms for recovering data on a website [33], thus, stressing the importance of recording web pages with search tools. Luh et al. [38] posited that efficiently designing an easy way for searchers to discover their way to specific sites is key to attracting increased website traffic. SEO provides endless concurrent knowledge regarding users’ online behaviors compared to traditional marketing methods.

Moreover, expenditure on web traffic from organic advertisements is exempted, making SEO more favorable to marketers [33]. According to Drivas et al. [39], users’ submission of search terms, observation of search results, clicking on organic search results, and visiting pages are demonstrations of interaction with search engines on a website. In e-commerce, online purchasers interact with search engines on e-commerce shopping platforms by searching for products, comparing prices, and scanning product information [33]. The rank of search results on the shopping platform is based on several quality factors, and it helps purchasers to formulate a decision on which product store to visit on the platform. A study of online shoppers’ behavior revealed that most shoppers interact with the first few results on the website based on the ranking [40]. Effortless access to an e-commerce platform by online shoppers requires marketers to reduce website load times and server stress, leading to retained shoppers and increased web traffic [40].

This study defines SEO as unpaid mechanisms, contrary to pay-per-click ads, on e-commerce shopping platforms that enable consumers to gain the most relevant results from their product searches. It focuses on consumers’ interest in continuous interactions with an e-commerce firm’s website induced by product search results. SEO, in this study, represents the environmental stimulus with the potential to trigger consumer responses.

2.3.2. Organic Social Media Posts

Social media posts are messages in texts, varied media formats (for instance, images and videos), and links to other content published on social media. The introduction of social media has altered the interaction mode between firms and consumers while serving as an invaluable channel for marketing. Firms post product or service-related content on social media and get consumers to engage by liking, sharing, and commenting on the content [11]. Previous studies have proposed varied conceptualizations of social media posts [7,11]. Deng et al. [11] evaluated firms’ posts on social media based on the post content, post media, and posting time and frequency. Gkikas et al. [7] studied branded social media image posts. They focused on the associated text characteristics (readability, text length, and the number of hashtags) as the defining elements of social media posts. Despite the extensive examination agreement on the conceptualization of social media posts as content characteristics, they vary concerning the context [7]. Previous studies, for example, have evaluated the emotional appeal of a post as opposed to informational appeal [41], the varied impact of different types of posts (links, videos, images) [42], the level of interactivity of a message [43], and the co-creation aspect of content [44]. As noticed, not enough research is conducted on other text-related characteristics (for instance, the level of complexity and formality) of firms’ social media posts, though there is confirmation of their significant influence on engagement with the firms in question [45]. The publication of these posts on social media by firms primarily has the followers of the firms’ social media fan page as targets, and no costs are involved in publishing such posts; thus, they are considered an organic marketing practice.

In this study, we examine the characteristics of posts published by e-commerce firms as the defining elements of social media posts and represent the external stimuli to consumers. This study evaluates the emotional, complex, informal, readable, and activation nature as elements of e-commerce firms’ social media posts.

2.3.3. User-Generated Content (UGC)

UGC refers to the publicly accessible SNS content created solely by nonprofessionals through recreational practices and routines [46]. In marketing, brand-related content created by anyone who is not a formal or authorized firm representative is termed UGC. It stemmed from consumer-produced content in images, audio, videos, blogs, and other forms of content contributed throughout social media. These consumers are unrewarded donators of content created to promote or disapprove of firms that consumers follow on social media platforms [47]. The criteria for content to be considered as UGC are that it must be published [48], it must be created by a content creator [49], and it must be created without reward [50]. UGC is characterized by endless variations, some of which are forums, user-created blogs, podcasts, reviews, user-created videos, social media posts, and comments [18]. Several studies have examined the concept of UGC in tourism, online shopping, social media, and advertising contexts [51,52].

Despite the extant investigation of UGC, fewer studies have focused on the organic (unrewarded) UGC. Kim and Song [53] posited that paid promotional content yields a more effective marketing result. Additionally, the effects of UGC have been chiefly measured on the purchase behavior or brand loyalty aspect of consumer behavior [51]. This study, motivated by this gap, examines the concept of unpaid firm-related content initially created and published by consumers or fans of an e-commerce firm who have no official ties to the firm on social media platforms. Specifically, we evaluate the UGC based on four elements: the consumer’s interest in the content, and the informing, pioneering, and co-communication nature of the content.

2.4. Attention to Social Comparison

ATSC refers to individuals’ sensitivity to the cues of society and the reaction concerns of others [54]. Previous researchers have used ATSC to examine individuals’ vulnerability to peer pressure and their long-term attitude toward conformity [55,56]. The underlying assumption of the concept is that individuals who try to avoid negative evaluations adhere significantly to social cues, and individuals with low self-esteem are generally more conforming to the pressures of social norms as they try to prevent disapproval [56,57,58]. According to Bearden and Rose [55], self-confident individuals rely more on information scrutiny and less on societal cues during decision-making. In summary, individuals with high (vs. low) ATSC rely more on social norms and concern about other people’s reactions to their decisions. Novak and Crawford [59] investigated ATSC as a moderating variable to assess its impact on the relationship between social norms and alcohol use. Yun and Silk [60] also studied the ATSC concept as a moderating variable and evaluated its effects on the relationship between exercise and a healthy diet.

Over the past years, studies have applied ATSC as a factor associated with consumer behaviors [61,62,63]. Attiq and Azam [61] investigated the association between ATSC and their buying behaviors in shopping malls. In the context of SNS, Phua et al. [62] examined the moderating effects of ATSC on the relationship between frequent use of social media and brand community-related outcomes. In the context of online shopping, Asante et al. [63] investigated how ATSC moderated the effects of consumers’ satisfaction with website attributes on their engagement formation.

However, most of these studies have concentrated more on the individual’s ATSC of information (i.e., ATSCI) and less on the ATSC of consumption (ATSCC). As demonstrated by Bearden and Rose [55], individuals with high (vs. low) ATSC worry about being judged by their purchases, attach great importance to interpersonal considerations in buying “branded” products, and adhere more to the preferences of peers in product choices. In bridging this gap, the current study defines ATSCC as consumers’ consciousness of the judgment of others on a social media platform regarding their own consumption choices. This study investigates how ATSCC moderates consumers’ formation of behavioral engagement on social media platforms triggered by organic marketing practices and psychological engagement.

2.5. Hypothesis Development

2.5.1. SEO, Psychology and Behavioral Engagement

SEO is an organic marketing strategy that enhances the visibility of a website when users search for products and services in search engines [64]. Optimizing a search engine is an effective marketing strategy for bloggers and online shopping platforms to boost visitor traffic [65]. A website page is processed to present relevant results to a search query. SEO, therefore, serves as a mechanism that allows consumers to obtain the most relevant result from their online search query. According to Raju [66], SEO improves the search results on online platforms and guarantees interactions with the most relevant result by the end users through visitations. The connection between SEO and consumer behavioral characteristics has been established by previous studies [67,68].

Despite establishing the relationship between SEO and consumers’ attitudes, only a handful of studies have investigated SEO’s impacts on the observable behaviors of consumers. This study subsumes consumer behavioral and psychological engagement attitudes from interactions with SEO on e-commerce shopping platforms. Specifically, when consumers perceive a satisfying SEO on a platform, they will form psychological engagement attitudes and participate in behavioral engagement attitudes. Based on the discussions above, we hypothesize that:

H1.

The e-commerce platform’s SEO directly influences the psychological engagement of consumers.

H2.

The e-commerce platform’s SEO directly influences the behavioral engagement of consumers.

2.5.2. Social Media Posts, Psychology, and Behavioral Engagement

Researchers have explored consumer engagement with social media brand-related posts from different viewpoints. Studies have investigated consumer engagement with content type, media type, posting time [69,70], message appeal, message richness [71,72], and brand post level [73]. A study by Deng et al. [11] evaluated post content, post media, and posting time and frequency as significant social media factors influencing consumer engagement. Researchers continuously investigate new ways to comprehend and predict consumer behavior toward brands on social media [74,75]. Although significant in digital marketing, consumer engagement with firms on social media lacks conceptualization and research [7]. Engagement with firms on social media represents the firms’ social media communities, made up of the firm, its products and services, and other consumers [67]; thus, the interaction with the firm involves a vaster process. In light of these, previous researchers have tried to clarify factors of firms’ social media posts that draw consumer engagement behaviors and increase conversions [42,44]. Notably, the interactions reflected by the number of likes and shares [44] and the type of posts [42] significantly impact engagement behaviors toward firms on social media.

Despite the clarity of the connection between firms’ social media posts and consumer engagement, minimal attention has been given to the complexity and formality levels of the firms’ social media posts. Also, the psychological engagement of consumers induced by these characteristics has been understudied. This study includes the complexity and formality attributes of an e-commerce firm’s social media posts and predicts their influence on consumer engagement. Consumers are expected to interact with social media posts that are less ambiguous and less formal. E-commerce firms create fan pages on social media where firm-related content is posted to attract interaction from the followers of the fan page. These posts serve as a free source of advertising (organic marketing) and tend to attract engagement attitudes from consumers. This study proposes that characteristics of social media posts by e-commerce firms tend to influence consumers’ psychological and behavioral engagement. We therefore hypothesize that:

H3.

Firms’ social media posts directly influence the psychological engagement of consumers.

H4.

Firms’ social media posts directly influence the behavioral engagement of consumers.

2.5.3. UGC, Psychology and Behavioral Engagement

Brodie et al. [22] defined consumer engagement as a psychological state that develops through an interactive experience with a principal entity. This definition presents a framework to justify the connection between UGC and consumer engagement. Engagement develops from an experience with a firm. Previous studies have confirmed that high engagement is motivated by consumer experiences that connect a firm to the personal values and goals of the consumer [76,77]. Thus, an instance of UGC is expected to attract consumer engagement behaviors if the generated content is associated with the consumers’ personal goals. Consumers used to be information recipients on social media; however, consumers have lately become creators of the information [8]. Consumers generate firm-related content on social media platforms to evaluate and share their personal experiences with the firm and interact with other consumers on the platforms. Consumers on the platform use these UGC as reference points when making decisions regarding interactions with the firm [78]. In the context of digital marketing, consumers would prefer consumption experiences from strangers to endorsers and celebrities hired by the firm. Thus, UGC is an organic marketing practice that plays a significant role as a firm’s promoter. A consumer who generates firm-related content on social media is led to amplifying the firm’s benefits (or disadvantages) to other platform consumers [79]. This activity is expected to attract engagement behaviors like comments, shares, recommendations, and likes toward the firm.

Although the connection of UGC to consumer engagement has been established, the co-communication aspect of UGC and the unobservable engagement aspect has been understudied. Co-communication is when consumers post firm-related content on a social media platform and tag the firm; the firm then reposts this content on its social media fan page to attract consumer interaction. Furthermore, when consumers establish an association between the UGC and their personal goal, they form a positive firm-related state of mind towards the firm in question. They are more willing to engage in observable interaction with the firm. This study evaluates co-communication as part of the factors defining UGC; the firm-related UGC on media platforms is expected to attract psychological and behavioral engagement attitudes from consumers. Based on the above discussion, the current study hypothesizes that:

H5.

The firm-related UGC directly influences psychological engagement.

H6.

The firm-related UGC directly influences behavioral engagement.

2.5.4. Psychology and Behavioral Engagement

Consumer engagement, a loyalty-related relationship, focuses mainly on devotion and trust owing to consumers’ continuous interaction with a firm [80]. Researchers in the context of e-commerce have posited that the consumer engagement concept is a process that begins with a formation of psychological attitudes, which in turn leads to behavioral attitudes toward e-commerce firms [63,81,82].

This paper defines consumer engagement as an attitude formation process represented by consumers’ psychological and behavioral engagement attitudes induced by their perceived interaction experience with organic marketing practices. Consumers form unobserved firm-related psychological engagement attitudes after an interactive experience with organic marketing practices. These unobserved attitudes are expected to initiate observed behavioral engagement attitudes toward the e-commerce firm. Based on the explanation above, we hypothesize that:

H7.

Consumers’ psychological engagement has a positive influence on their behavioral engagement.

2.5.5. The Mediating Role of Psychology Engagement

Studies in consumer-brand relationships have established the significant mediating role of unobservable engagement in consumer perceptions and observable behavioral intentions [83,84]. Considering unobservable engagement is a psychological state that occurs in the process of the perceived service experience [22], several scholars employ it as a mediating factor in the relationship between consumers’ perceived interactions and behavioral attitudes [85,86].

Though previous studies support the mediating role of psychological engagement, it has been understudied in digital marketing research. In organic marketing, consumers participate in observable behavioral engagement after a perceived interaction experience with the organic marketing practices. However, this behavioral engagement is explained by consumers’ psychological engagement, characterized by vigor, absorption, and dedication towards the firm. Based on the discussion above, SEO on e-commerce platforms, social media posts of the e-commerce firm, and the firm-related UGC are expected to indirectly influence consumers’ participation in behavioral engagement through psychological engagement. Accordingly, this study hypothesizes that:

H8a.

Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between the e-commerce platform’s SEO and behavioral engagement.

H8b.

Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between firms’ social media posts and behavioral engagement.

H8c.

Psychological engagement mediates the relationship between firm-related UGC and behavioral engagement.

2.5.6. The Moderating Role of ATSCC

ATSC refers to consumers’ awareness and sensitivity to the reactions of other consumers regarding their own consumption choices or behaviors [56]. Studies have shown that individuals with high ATSC are less likely to share transaction experiences when they consume products tagged as “less prestigious” brands by social rating [87,88]. For instance, a consumer may enjoy a satisfying interaction experience on an e-commerce platform and be hardly triggered to perform any observable behavioral engagement attitude. The decision to not engage might be because the product they purchased is considered “inferior” (concerning the brand name) by society, therefore they hesitate in sharing the interaction experience to avoid a faux pas. Consumers’ ATSC, therefore, plays a vital role in the engagement formation process. Consumer behavioral researchers were faced with the issue of explicitly clarifying the circumstances under which normative influences play an essential part regarding behavioral intentions. Over the past years, studies have applied ATSC as a moderating factor associated with consumer behaviors [54,62,63]. As demonstrated by Bearden and Rose [55], high (vs. low) ATSC individuals are concerned about criticisms from others regarding their purchases, attach great importance to interpersonal considerations in buying branded products, and conform to peer preferences during consumption decisions. Thus, confirming the significant role played by consumers ATSC in affecting the process of consumer engagement.

The concept in this study defines how an individual will reduce their behavioral engagement attitudes toward an e-commerce platform on social media despite perceived interaction experience with the organic marketing practices. Consumers are willing to engage in e-commerce-related behavioral activities after a perceived interaction experience with the SEO of the e-commerce platform, firms’ social media posts, firm-related UGC on social media, and forming a positive state of mind towards the e-commerce firm. However, the degree of consumers’ attention to the social comparison of consumption alters the intensity of willingness to engage behaviorally. The current study, therefore, hypothesize that:

H9a.

ATSCC moderates the positive effects of e-commerce platform’ SEO on behavioral engagement.

H9b.

ATSCC moderates the positive effects of e-commerce firms’ social media posts on behavioral engagement.

H9c.

ATSCC moderates the positive effects of firm-related UGC on behavioral engagement.

H9d.

ATSCC moderates the positive effects of psychological engagement on behavioral engagement.

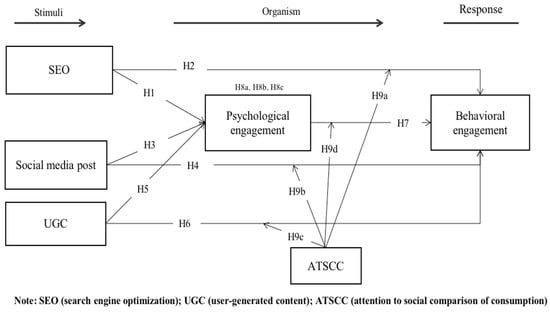

A summary of the hypothesized relationship is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

These firms expand their online presence by creating fan pages and building online communities on social media platforms. Members of the online community and followers of the fan pages on social media are consumers who use the e-commerce shopping platform to meet their transaction needs. Therefore, this study gathered responses from followers of selected e-commerce firms’ social media fan pages on Facebook. The study used the Similarweb web analytics platform to ensure that the chosen firms depict higher industry ranking (top 5), web traffic, and engagement regarding e-commerce and shopping/marketplace. Among the five e-commerce firms, Aliexpress is a Chinese-owned firm that operates from China and serves consumers globally. It ranks number six in the e-commerce and online shopping marketplace industry, indicates the performance of Chinese e-commerce firms on the global level [89]. The pool of items was adapted from the literature review, and a panel of academic experts in the field of digital marketing then evaluated the items for content and face validity. The panel ruled on the survey quality based on presentation, content, and structure. We pre-tested the questionnaires with 45 international undergraduate and graduate students at a large university in China. The respondents confirmed the clarity of the questionnaire and the responses from the pilot test confirmed the validity of the instrument. The study solicited primary data through questionnaire hyperlinks posted on the social media fan pages of the e-commerce firms every day for a month (1 June 2022, to 30 June 2022). The study adopted convenience sampling, a non-probability sampling method widely employed in studies where drawing random probability sampling is impossible due to the context [36]. The target respondents were the followers of e-commerce firms’ social media fan pages on Facebook. A total of 464 valid responses were obtained, with 354 males and 110 females. The respondents were of different ages and educational levels, with 40.1% being 20–30 years old and 35.1% with graduate education levels. All respondents were followers of at least one of the e-commerce firm’s Facebook fan pages, and most patronized the Amazon.com e-commerce platform more frequently (41.4%). Table 1 presents the respondents’ demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents.

3.2. Measures Development

All measures were adapted from established studies and modified to fit the current research context, permitting high reliability and validity of constructs (see Appendix A). The primary constructs were measured as first-order reflective constructs with multiple indicators. The variable indicators were all measured with a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 7.

3.2.1. Independent Variable

The four items measuring SEO came from Bhandari and Bansal [33] and Drivas et al. [39] and were adjusted based on the characteristics of e-commerce shopping platforms. They measure the ability of an unpaid optimized search engine to boost consumer insights, time spent on visits, pages viewed within a visit, and the persuasion of the visit meeting consumer needs.

The five items measuring social media posts were adapted from Gkikas et al. [7], Deng et al. [11], and Demmers et al. [73] to fit the organic marketing context of e-commerce, where firms post firm-related content on social media platforms to draw engagement from their consumers naturally. The items measure the readable, emotional, complex, informal, and activation nature of the content posted by e-commerce firms.

Finally, the four items of UGC came from Thomas [8]. They were adjusted to fit the organic marketing context where consumers generate and post e-commerce firm-related content on Facebook, without any sort of remuneration from the e-commerce firms, to share their interaction experience to benefit other consumers. The items measure the interest, informing, pioneering, and co-communication features attached to consumer-generated content.

3.2.2. Mediating Variable

The three items of the mediating variable, psychological engagement, were adapted from Habib et al. [90] and adjusted to examine the unobservable psychological engagement from consumers. The items measure the feeling of vigor, absorption, and dedication experienced by consumers based on their interaction with the organic marketing practices of the e-commerce firm.

3.2.3. Moderating Variable

The four items measuring the moderator variable, ATSCC, were adapted from Yoon et al. [54] to fit the context of organic marketing, where consumers experience a satisfying interaction with the organic marketing practices of an e-commerce firm. However, the intensity of consumers’ behavioral engagement is determined by how they compare their consumption choices with other consumers. The items measure consumers’ sensitivity to embarrassment, social consumption comparison, maintaining conformity, and the reaction of others to their consumption choices.

3.2.4. Dependent Variable

The five items measuring behavioral engagement came from Brodie et al. [26] and Eslami et al. [44]. They were adjusted to fit consumers’ behavioral engagement activities on social media towards organic marketing practices of e-commerce firms. The items measure consumers’ eWOM, likes, comments, shares, and loyalty.

4. Data Analysis and Results

The research model was estimated using the traditional covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) technique through Stata 16. The S-O-R paradigm is an already established model. This study aims to apply the model in the context of organic marketing to explain the current study’s model parameters, therefore, choosing CB-SEM. The first step of data analysis involved testing the reliability and validity of the measurement scales using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The second step involved testing the structural relationship among the latent constructs utilizing the structural equation modeling procedure.

4.1. Measurement Model

The Doornik-Hansen omnibus test for multivariate normality indicated that the variables do not come from a normal distribution (X2 (12) = 3624.16, p < 0.01). Thus, the study selected a maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and the Satorra-Bentler scaled test statistics to assess the research model, compensating for nonnormality variables [91]. CFA was employed to estimate the measurement model. The result of the CFA in Table 2 presents composite reliability (CR), and average variance explained (AVE) values above 0.70 and 0.50, respectively, for all constructs. The result confirms the reliability of the constructs [92]. Factor loading for all measurement items exceeded 0.7 with significant t-values (t > 1.96, p < 0.05), indicating adequate convergent validity for all indicators [92].

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

The discriminant validity was assessed using the item-to-construct correlation matrix, the Fornell and Larcker criterion, and the heterotrait-monotrait ratios of correlation (HTMT). As presented in Table 3, the loadings of items assigned to specific constructs are higher than those on all other constructs, thus, indicating adequate discriminant validity [92]. Table 4 shows the square root of each construct’s AVE (on the diagonal) is greater than the correlation between constructs (off the diagonal); therefore, discriminant validity is established [93]. Table 5 presents HTMT values lower than the strictest threshold of 0.85 (the maximum being 0.802), indicating that discriminant validity is established [94].

Table 3.

Item-to-construct correlation matrix.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and Fornell-Larcker discriminant validity criterion.

Table 5.

The heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

Before testing the hypothesized paths, the study assessed the structural model fit and collinearity issues. The model fit evaluation employed multiple fit indices, including chi-square/degree of freedom (X2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis’ index (TLI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). The results in Table 6 satisfy the recommended fitness criteria, indicating that the structural model fits well with the data set used in the study [95]. Moreover, the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all exogenous variables was estimated to assess the issue of collinearity. The result in Table 7 displays significant VIF values (≤5) and tolerance levels (≥ 0.2), ruling out collinearity issues [96].

Table 6.

Fit indices of the structural model.

Table 7.

Collinearity assessment.

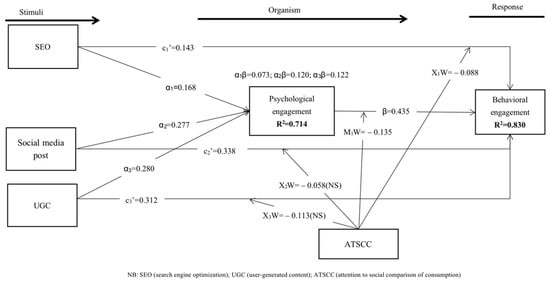

As shown in Figure 2, the proposed model explained 83% and 71.4% of behavioral and psychological engagement variations, respectively. The proposed hypotheses were tested and grouped into three parts based on the research model: direct, mediating, and moderating effects. The results of the structural model are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural model results.

4.2.1. Direct Effects

The proposed direct effects of the study were significant, with p-values < 0.05 and t-values > 1.96. Particularly, SEO has positive significant direct effects on psychological (β = 0.168, p < 0.001, t-value = 5.781, H1 supported) and behavioral (β = 0.143, p < 0.001, t-value = 4.712, H2 supported) engagement. Social media posts have positive significant direct effects on psychological (β = 0.277, p < 0.001, t = 5.864, H3 supported) and behavioral (β = 0.338, p < 0.001, t = 6.861, H4 supported) engagement. UGC has positive significant direct effects on psychological (β = 0.280, p < 0.001, t = 5.970, H5 supported) and behavioral (β = 0.316, p < 0.001, t = 6.332, H6 supported) engagement. As expected, psychological engagement influences behavioral engagement (β = 0.435, p < 0.001, t = 9.261, H6 supported).

4.2.2. Mediating Effects

To test the mediating effect of psychological engagement on the relationships between organic marketing and behavioral engagement, this study used the adjusted Baron and Kenny approach to test the mediation effects [97]. This approach considers four steps in determining the presence of mediation in a model. The first step assesses the direct relationship between the independent and the moderating variable (X → M). The second step is estimating the direct connection between the mediating and the dependent variable (M → Y). The third step is assessing the direct relationship between the independent and the dependent variable (X → Y), and the fourth step depends on the significance of the Sobel test of mediation (z-value ≥ 1.96, p ≤ 0.05, confidence interval should exclude 0). According to this approach, there is no mediation if both or one of the X→M and M→Y are not significant.

Additionally, there is complete mediation if Sobel’s z-test is significant but X→Y is not. Finally, there is partial mediation if all four steps are significant [97]. As long as steps one, two, and three and the Sobel test in Table 8 are concerned, psychological engagement mediates the relationships between organic marketing and behavioral engagement.

Table 8.

Results of hypothesized mediating and moderating effects.

4.2.3. Moderating Effects

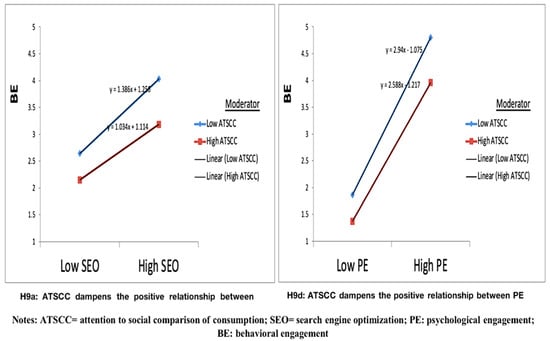

The moderating effects of ATSCC were tested using a bootstrapping approach to obtain standard errors and confidence intervals. This approach better reflects the sampling distribution of the conditional indirect impact as the biased corrected and percentile confidence intervals are nonsymmetric [98]. A moderation is confirmed at an absolute t-value > 1.96 with a bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero. That is, the range from bootstrap lower-level confidence interval (BootLLCI) to bootstrap upper-level confidence interval (BootULCI) must not include zero to confirm the moderating effect [98,99]. As presented in Table 8, the interaction effect of ATSCC on the relationship between SEO and behavioral engagement was negative and statistically significant. The interaction effect of ATSCC on the relationship between psychological and behavioral engagement was negative and statistically significant. However, there was no significant interaction effect of ATSCC on the relationships between social media posts and behavioral engagement, as well as UGC and behavioral engagement; thus, hypotheses H9b and H9c are not supported. The interaction slopes of the significant hypothesized moderating effects (H9a and H9d) are displayed in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Interaction slopes of the significant moderating effects.

5. Discussions

There is a scientific accord on the importance of digital marketing in maintaining positive consumer engagement and ensuring the success of firms [7,8,31,32,100]. There is, however, a lack of studies investigating the effects of organic (unpaid) digital marketing strategies on consumer engagement. The empirical results from the study’s analysis point to findings uncovered by previous research.

First, findings established SEO on e-commerce shopping platforms, social media posts of e-commerce firms, and UGC as the organic practices in marketing that drive psychological and behavioral engagement on social media platforms. The results also confirmed a direct influence of psychological engagement on behavioral engagement. Notably, e-commerce firms’ social media posts exerted the highest impact on behavioral engagement among organic marketing practices. A possible explanation is that the respondents react more to social media content posted by the e-commerce firm. These findings indicate the variations in the effectiveness of different practices in attracting consumer engagement. The findings somehow contradict previous studies that posited that technology-aided services reduced consumer participation [101].

Additionally, the mediating effect of psychological engagement between organic marketing practices and behavioral engagement was uncovered. Concerning Brodie et al. [22], the current study operationalized consumer engagement as a process initiated by consumers’ experience with the organic marketing practices available to a firm. The process begins with expressing some e-commerce firm-related unobservable attitudes (psychological engagement) that trigger observable behaviors (behavioral engagement). The results confirmed psychological engagement as the organism in the S-O-R model that partially mediates the effects of the stimuli (organic marketing practices) on consumer response (behavioral engagement). A possible explanation is that consumers’ behavioral engagement towards an e-commerce firm, caused by interactions with organic marketing practices, is partially explained by the presence of consumers’ psychological engagement with the firm. However, the confirmed positive mediating effect of psychological engagement contradicts the studies of Cheng et al. [102] who found no significant mediating effect of the psychological construct, perceived risk, on the relationship between technology-aided services on a ridesharing app and consumer participation.

Third, the moderating effects of ATSCC were revealed. Consumers’ ATSCC dampened the positive impact of SEO and psychological engagement on behavioral engagement. These findings suggest that the intensity of behavioral engagement attitudes toward e-commerce firms tends to reduce for consumers with high (vs. low) attention to social comparison of consumption choices. When consumers care too much about what society thinks of their consumption choices, they are reluctant to participate in observable behavioral attitudes. However, a satisfying SEO interaction is perceived, and a psychological engagement is formed. These findings are in line with the works of Kim et al. [103] and Asante et al. [63].

Conversely, ATSCC did not moderate the effects of social media posts and UGC on behavioral engagement. A possible explanation is that social media posts and UGC will trigger consumers’ behavioral engagement attitudes on social media, irrespective of their ATSCC. This outcome is because consumers’ observable reactions to social media posts and UGC on social media platforms generally do not involve the disclosure of product consumption choices.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

A significant contribution of the current study is the investigation of organic marketing, focusing on unpaid marketing practices that increase consumer engagement. This study is one of the first to investigate consumer engagement induced by interactions with e-commerce firms’ organic marketing practices. In adapting the S-O-R paradigm to the digital marketing context, we theoretically revealed the relationships between organic marketing practices, consumers’ attention to social comparison of consumption choices, psychological engagement, and behavioral engagement and tested these relationships empirically.

The study’s findings provide new insights into digital marketing literature by exploring unpaid marketing practices on e-commerce platforms and social networking sites. The study augments the digital marketing knowledge base by empirically identifying varied organic marketing practices that convert consumers and generate web traffic devoid of paid advertisement. The factors considered in this study accounted for a significant variation (above 80 percent) in consumers’ behavioral engagement, suggesting the importance of organic marketing practices in driving consumer engagement behaviors. The study shows that psychological engagement significantly mediates the effects of organic marketing practices on behavioral engagement. This finding confirms that consumer engagement is an attitudinal process that begins with psychological engagement and triggers consumers’ behavior.

Moreover, the current study improves existing literature by uncovering the interaction effect of consumers’ attention to social comparison that influences the positive impacts of SEO and psychological engagement on behavioral engagement. The findings revealed the negative moderated relationship between SEO and behavioral engagement. Additionally, the results showed that the relationship between psychological and behavioral engagement was negatively moderated. These two negatively moderated relationships advance our understanding of how the intensity of behavioral engagement antecedents is weakened (or strengthened) when consumers have high (or low) ATSCC.

5.2. Practical Implications

Practically, the findings assist managers of e-commerce shopping platforms in understanding the organic marketing practices that attract the most consumer traffic, thus, effectively ascertaining psychological and behavioral engagement. Managers of e-commerce shopping platforms should spend more time improving the unpaid marketing practices that directly and indirectly attract consumers’ behavioral engagement. The study’s results suggest that social media posts from e-commerce firms have the most apparent effect on consumers’ behavioral engagement. Thus, advising firms to update posts about product information, discount, and promotional packages frequently attracts consumer traffic.

Additionally, psychological engagement significantly mediated the effect of organic marketing practices on behavioral engagement. This finding implies that consumers form a positive firm-related state of mind during their interaction with organic marketing practices, which triggers observable behavioral attitudes like commenting on firms’ social media posts and participating in eWOM. Firms could increase traffic by tailoring the shopping platforms to specific consumers based on their search history, designing product-related social media posts, and encouraging UGC that influence consumers’ positive firm-related state of mind.

Moreover, the finding suggests that the intensity of observable behavioral engagement attitudes caused by interactions with the SEO on the shopping platform and consumers’ psychological engagement is weakened for consumers with high ATSCC. Implying that e-commerce firms should ensure only products and services that meet the quality standard should be marketed to attract consumer engagement. Finally, the findings indicate that observable behavioral engagement attitudes from consumers will increase as they interact with the firm’s social media posts and UGC, irrespective of the consumers’ high or low ATSCC status. E-commerce firms could improve the quality of product-related social media content and simultaneously encourage quality UGC to attract significant volumes of observable behavioral engagement.

5.3. Limitations and Proposed Future Research

Despite the theoretical and practical implications, the study is not without limitations. These limitations can, however, serve as future research directions. First, a quantitative methodology was employed for this study; a mixed method can be considered in future studies to expand the understanding of organic marketing practices available to e-commerce firms. Additionally, a cross-sectional study was adopted for the current research. Future studies can counter this limitation by adopting a longitudinal design to examine the variations in web traffic over time.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the impacts of organic marketing practices available to e-commerce firms on consumer engagement. The findings show that consumer engagement is an attitude formation process that begins with psychological engagement attitudes and triggers observable behavioral engagement activities. Secondly, the results show that some organic practices have higher impacts on consumer engagement compared to others. Specifically, organic social media posts significantly influence behavioral engagement more than SEO and UGC. Finally, high attention to social comparison of consumption was found to weaken the strength of the positive effects of SEO and psychological engagement on behavioral engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, and validation: I.O.A. and Y.J.; formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation: I.O.A. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation: I.O.A.; writing—review and editing: I.O.A. and M.A.T.; visualization: Y.J. and M.A.T.; supervision: I.O.A.; project administration: Y.J. and X.L.; funding acquisition: I.O.A. and Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72172129.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was waived from “ethical review and approval” as it was conducted based on survey responses from the followers of brands’ social media pages, which is to social science-based research and not relevant to any human/clinical trials.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Scales

| Construct | Measurement Scales |

| Search engine optimization (SEO) [33,39] | When I am on the e-commerce shopping platform: |

| 1. The keywords I type in the search engine produces search results that matches what I’m looking for. | |

| 2. I spend a lot of time surfing the online store I choose to visit from the search result. | |

| 3. I browse more pages within the online store I visit. | |

| 4. The online store I visit usually have exactly what I need. | |

| Social media posts (SMP) [7,11,73] | When I am on the firm’s Facebook fan page: |

| 5. The e-commerce firm’s social posts are easy to understand. | |

| 6. The e-commerce firm’s social posts are concise and free of ambiguity. | |

| 7. The e-commerce firm’s social posts usually appeal to my emotions. | |

| 8. The e-commerce firm’s social posts convey close relationships with the brand because they are more casual and familiar. | |

| 9. The e-commerce firm’s social posts have features like product link, polls and questions that invite me to interact with the posts. | |

| User-generated content (UGC) [8] | When I am on the firm’s Facebook fan page: |

| 10. I like to read the e-commerce firm-related posts from other consumers. | |

| 11. I find the e-commerce firm-related posts from other consumers as a credible information source. | |

| 12. Other consumers share knowledge of the usage efficiency of firm’s e-commerce platform on social. | |

| 13. Some e-commerce firm-related posts on social media are a repost of consumers consumption review. | |

| Psychological engagement (PE) [90] | 14. I feel no stress when interacting with the e-commerce platform and social media contents related to the e-commerce firm. |

| 15. I am enthused and inspired when I am interacting with the e-commerce platform and social media contents related to the e-commerce firm. | |

| 16. I do not realize the passage of time as I am interacting with the e-commerce platform and social media contents related to the e-commerce firm. | |

| Behavioral engagement (BE) [26,44] | 17. I share my opinions and relay information about my experience with the e-commerce firm on the social media platform. |

| 18. I do “like” the e-commerce firm’s social media posts. | |

| 19. I comment on the social media posts of the e-commerce firm on the social media platform. | |

| 20. I share the social media posts of the e-commerce firm on my social media platform. | |

| 21. I am willing to remain a follower of the e-commerce firm’s social media fan page. | |

| Attention to social comparison (ATSCC) [54] | 22. It is important for me to purchase a specific brand of product that everyone is patronizing on the e-commerce platform. |

| 23. If everyone is purchasing a certain brand of product on the e-commerce platform, I feel it is the best to have that. | |

| 24. If I am unsure about what to purchase, I usually look at what people buy most. | |

| 25. I tend to pay attention to what most people are consuming. |

References

- Han, W. Purchasing Decision-Making Process of Online Consumers Based on the Five-Stage Model of the Consumer Buying Process. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Public Relations and Social Sciences, Kunming, China, 17–19 September 2021; Volume 586, pp. 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Organic Marketing? Available online: https://www.ondemandcmo.com/blog/what-is-organic-marketing/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Vieira, V.A.; Almeida, M.I.S.; Agnihotri, R.; da Silva, N.S.D.A.C.; Arunachalam, S. In Pursuit of an Effective B2B Digital Marketing Strategy in an Emerging Market. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Yan, X. Impact of Firm-Generated Content on Firm Performance and Consumer Engagement: Evidence from Social Media in China. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, A.; Shah, A.; Kansara, K.; Bhagubhai, S.; Polytechnic, M.; Bhagubhai, S.; Polytechnic, M. Digital Marketing—Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and Search Engine Marketing (SEM). Int. Res. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mukul, E. Evaluation of Digital Marketing Technologies with MCDM Methods. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Ideas in Management, Economics and Accounting, Paris, France, 19 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gkikas, D.C.; Tzafilkou, K.; Theodoridis, P.K.; Garmpis, A.; Gkikas, M.C. How Do Text Characteristics Impact User Engagement in Social Media Posts: Modeling Content Readability, Length, and Hashtags Number in Facebook. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.G. How User Generated Content Impacts Consumer Engagement. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions); Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Noida, India, 1 June 2020; pp. 562–568. [Google Scholar]

- D’Eletto, V. What Is Organic Marketing? (Benefits, Tips, and Strategies). Available online: https://www.wordagents.com/organic-marketing/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Elrod, J.K.; Fortenberry, J.L. Public Relations in Health and Medicine: Using Publicity and Other Unpaid Promotional Methods to Engage Audiences. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Hine, M.J.; Ji, S.; Wang, Y. Understanding Consumer Engagement with Brand Posts on Social Media: The Effects of Post Linguistic Styles. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 48, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, E.C.; Calder, B.J.; Kim, S.J.; Vandenbosch, M. Evidence That User-Generated Content That Produces Engagement Increases Purchase Behaviours. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorn, V.J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior—Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.; Kunz, W. How to Transform Consumers into Fans of Your Brand. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demangeot, C.; Broderick, A.J. Engaging Customers during a Website Visit: A Model of Website Customer Engagement. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 814–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer Engagement: The Construct, Antecedents, and Consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarondo, L.; Kennedy, K.; Kay, D. Development of a Consumer Engagement Framework. Asia Pacific J. Health Manag. 2016, 11, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulio, Z.M.; Getulio, V.F.; Paulo, S.; Vitor, L.B.; Migueles, C.; Lourenco, F.G.V.C.; Arthur, R.I.H. Soccer and Twitter: Virtual Brand Community Engagement Practices Fábio Carbone de Moraes. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.K.H.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O.; Lee, Z.W.Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Engagement in Online Brand Communities. J. Mark. Anal. 2014, 2, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbach, J.; Lages, C.; Nunan, D. Consumer Engagement in Online Brand Communities: The Moderating Role of Personal Values. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1671–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C.M. Customer Engagement, Buyer-Seller Relationships, and Social Media. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, A.; Pinho, E.; Rodrigues, P. Antecedents and Consequences of Luxury Brand Engagement in Social Media. Spanish J. Mark.-ESIC 2019, 23, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Tuten, T. Creative Strategies in Social Media Marketing: An Exploratory Study of Branded Social Content and Consumer Engagement. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Yu, T.; De Ruyter, K. Understanding Customer Engagement in Services. In Advancing Theory, Maintaining Relevance, Proceedings of ANZMAC 2006 Conference, Brisbane; Queensland University of Technology (QUT) publishing: Brisbane, Australia, 2006; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer Engagement in a Virtual Brand Community: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.L.-H. The Process of Customer Engagement: A Conceptual Framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Tariq, A.; Ali, M.W.; Nawaz, M.A.; Wang, X. An Empirical Investigation of Virtual Networking Sites Discontinuance Intention: Stimuli Organism Response-Based Implication of User Negative Disconfirmation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 862568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Chen, C.W. Impulse Buying Behaviors in Live Streaming Commerce Based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response Framework. Information 2021, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, M.H.M.; Dolatabadi, H.R.; Dashti, M.; Sanayei, A. Application of the Stimuli-Organism-Response Framework to Factors Influencing Social Commerce Intentions among Social Network Users. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2019, 30, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghizzawi, M. The Role of Digital Marketing in Consumer Behavior: A Survey. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Lang. Stud. 2019, 3, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Diges, L.; Debasa, F. The Use of Digital Marketing Strategies in the Sharing Economy: A Literature Review. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 8, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, R.S.; Bansal, A. Impact of Search Engine Optimization as a Marketing Tool. Jindal J. Bus. Res. 2018, 7, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirisha, P.; Laxmiprasanna, A. Amanote. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.-P.; Depari, G.S. Paid Advertisement on Facebook: An Evaluation Using a Data Mining Approach. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sanne, P.N.C.; Wiese, M. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and User Engagement Applied to Facebook Advertising. SA J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderl, E.; März, A.; Schumann, J.H. Nonmonetary Customer Value Contributions in Free E-Services. J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 24, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luh, C.J.; Yang, S.A.; Huang, T.L.D. Estimating Google’s Search Engine Ranking Function from a Search Engine Optimization Perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drivas, I.C.; Sakas, D.P.; Giannakopoulos, G.A.; Kyriaki-Manessi, D. Search Engines’ Visits and Users’ Behavior in Websites: Optimization of Users Engagement with the Content. Springer Proc. Bus. Econ. 2021, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cabage, N. Search Engine Optimization: Comparison of Link Building and Social Sharing. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2016, 57, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Gómez, M.; Lyon, A.; Aranda, E.; Loibl, W. What Content to Post? Evaluating the Effectiveness of Facebook Communications in Destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaoui, C.; Webster, C.M. Brand and Consumer Engagement Behaviors on Facebook Brand Pages: Let’s Have a (Positive) Conversation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Paul, J.; Strong, C.; Pius, J. Consumer Response towards Social Media Advertising: Effect of Media Interactivity, Its Conditions and the Underlying Mechanism. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, S.P.; Ghasemaghaei, M.; Hassanein, K. Understanding Consumer Engagement in Social Media: The Role of Product Lifecycle. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 162, 113707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.W.; Horváth, C.; Gretry, A.; Belei, N. Say What? How the Interplay of Tweet Readability and Brand Hedonism Affects Consumer Engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naem, M.; Okafor, S. User-Generated Content and Consumer Brand Engagement. In Leveraging Computer-Mediated Marketing Environment; IG Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, S.; Thorson, E. Digital Advertising: Theory and Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781138654457. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, E.; Wang, Y. Blogging the Brand: Meaning Transfer and the Case of Weight Watchers’ Online Community. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Ertz, M.; Jo, M.S.; Sarigollu, E. Social Value, Content Value, and Brand Equity in Social Media Brand Communities: A Comparison of Chinese and US Consumers. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, S.; Christodoulides, G.; Presi, C.; Wenhold, J.; Casaletto, J.P. Consumer Trust in User-Generated Brand Recommendations on Facebook. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Chen, J. The Influencing Mechanism of Interaction Quality of UGC on Consumers’ Purchase Intention—An Empirical Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 697382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Ko, E. UGC Attributes and Effects: Implication for Luxury Brand Advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 945–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Song, D. When Brand-Related UGC Induces Effectiveness on Social Media: The Role of Content Sponsorship and Content Type. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 37, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.J.; La Ferle, C.; Edwards, S.M. A Normative Approach to Motivating Savings Behavior: The Moderating Effects of Attention to Social Comparison Information. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Rose, R.L. Attention to Social Comparison Information: An Individual Difference Factor Affecting Consumer Conformity. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 16, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, R.D.; Wolfe, R.N. Revision of the Self-Monitoring Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. The Nature of Attitudes and Attitude Change. In The Handbook of Social Psychology; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 3, pp. 136–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.F.; Bauer, R.A. Self-Confidence and Persuasibility in Women on JSTOR. Public Opin. Q. 1964, 28, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, K.B.; Crawford, L.A. Perceived Drinking Norms, Attention to Social Comparison Information, and Alcohol Use among College Students. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2001, 46, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, D.; Silk, K.J. Social Norms, Self-Identity, and Attention to Social Comparison Information in the Context of Exercise and Healthy Diet Behavior. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attiq, S.; Azam, R.I. Attention to Social Comparison Information and Compulsive Buying Behavior: An S-O-R Analysis. J. Behav. Sci. 2015, 25, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J. Gratifications of Using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to Follow Brands: The Moderating Effect of Social Comparison, Trust, Tie Strength, and Network Homophily on Brand Identification, Brand Engagement, Brand Commitment, and Membership Intentio. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, I.O.; Fang, J.; Darko, D.F. Consumers’ Role in the Survival of e-Commerce in Sub-Saharan Africa: Consequences of e-Service Quality on Engagement Formation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–19 October 2019; pp. 0763–0770. [Google Scholar]

- Karisma, I.A.; Darma Putra, I.N.; Wiranatha, A.S. The Effects of “Search Engine Optimization” on Marketing of Diving Companies in Bali. E-J. Tour. 2019, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, T.; Sani, A.; Ardhiansyah, M.; Wiliani, N. Online Shop as an Interactive Media Information Society Based on Search Engine Optimization (SEO). Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2020, 68, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.C. Search Engine Optimization: A Digital Marketing Giant and Need of Time. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Multidiscip. Phys. Sci. 2019, 7, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Issá, R.; Ribeiro, M.; Marques, D.S.; Jose, P. Structuring Best Practices of Search Engine Optimization for Webpages. Smart Innov. Syst. Technol. 2022, 279, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, A.; Arilla, R.; Ponzoa, J.M. Search Engine Optimization: The Long-Term Strategy of Keyword Choice. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.D. Proposing to Your Fans: Which Brand Post Characteristics Drive Consumer Engagement Activities on Social Media Brand Pages? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2017, 26, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.S.I.; Pratt, S.; Wang, D. Factors Influencing Customer Engagement with Branded Content in the Social Network Sites of Integrated Resorts. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.F.; Baccarella, C.V.; Voigt, K.I. Framing Social Media Communication: Investigating the Effects of Brand Post Appeals on User Interaction. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swani, K.; Milne, G.R.; Brown, B.P.; Assaf, A.G.; Donthu, N. What Messages to Post? Evaluating the Popularity of Social Media Communications in Business versus Consumer Markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 62, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmers, J.; Weltevreden, J.W.J.; van Dolen, W.M. Consumer Engagement with Brand Posts on Social Media in Consecutive Stages of the Customer Journey. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2020, 24, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, X.; Shen, S.; He, D. Social Media Opinion Summarization Using Emotion Cognition and Convolutional Neural Networks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.K.; Kar, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Predicting Retweet Class Using Deep Learning. In Trends in Deep Learning Methodologies: Algorithms, Applications, and Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 89–112. ISBN 9780128222263. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, B.J.; Isaac, M.S.; Malthouse, E.C. How to Capture Consumer Experiences: A Context-Specific Approach To Measuring Engagement. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hern, M.S.; Kahle, L.R. The Empowered Customer: User-Generated Content and the Future of Marketing. Glob. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2013, 18, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.Y.; Heng, C.S.; Lin, Z. Social Media Brand Community and Consumer Behavior: Quantifying the Relative Impact of User- and Marketer-Generated Content. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Roumani, Y.; Nwankpa, J.K.; Hu, H.-F. Beyond Likes and Tweets: Consumer Engagement Behavior and Movie Box Office in Social Media. Inf. Manag. 2016, 54, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wu, S. The Impacts of Technological Environments and Co-Creation Experiences on Customer Participation. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Işık, Ö.; Tona, O.; Popovič, A.; Is, Ö. How System Quality Influences Mobile BI Use: The Mediating Role of Engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer Engagement with Tourism Social Media Brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrilees, B.; Merrilees, B. Interactive Brand Experience Pathways to Customer-Brand Engagement and Value Co-Creation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, A.; Junco-Guerrero, M.; Cantón-Cortés, D. Exploring the Mediating Effect of Psychological Engagement on the Relationship between Child-to-Parent Violence and Violent Video Games. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.; Teng, H.; Tzeng, J. International Journal of Hospitality Management Innovativeness and Customer Value Co-Creation Behaviors: Mediating Role of Customer Engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Sung, Y.; Kang, H. Brand Followers’ Retweeting Behavior on Twitter: How Brand Relationships Influence Brand Electronic Word-of-Mouth. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 37, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Fan, W.; Chau, P.Y.K. Determinants of Users’ Continuance of Social Networking Sites: A Self-Regulation Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similarweb. Website Analysis Tools: Official Measure of the Digital World; 2022. Available online: https://www.statshow.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Habib, S.; Hamadneh, N.N.; Hassan, A. The Relationship between Digital Marketing, Customer Engagement, and Purchase Intention via OTT Platforms. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 5327626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Z.; Katz-Navon, T.; Naveh, E. The Influence of Situational Learning Orientation, Autonomy, and Voice on Error Making: The Case of Resident Physicians on JSTOR. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A Practical Guide To Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial And Annotated Example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]