1. Introduction

In a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) era, where organizations constantly face the unknown, employees are the most reliable source for enterprises to improve their core competitiveness. According to the 2020 Global Human Capital Trends report released by Deloitte, work engagement ranks in the top three human capital trends [

1]. Some scholars have proposed that work engagement is one of the most robust predictors of employee performance [

2]. Despite work engagement’s tremendous value in producing positive employee, team, and organizational outcomes, it should be noted that employees should not invest their dedication at the cost of their capability and health in the future. Engaging at work costs energy, which could develop a health-impairment process for employees without sufficient replenishment of resources [

3]. Such health complaints undermine employees’ motivation and performance and harm the organization’s sustainable development [

4]. Given the unpredictable risks of maintaining competitiveness and the grand challenge of facilitating sustainable human resource management in the VUCA era, neither supervisors nor staff can work alone. They must work together to enrich work resources that benefit employees’ sustainable development and meet the new era’s challenges.

In practice, cooperation between supervisors and subordinates often displays different characteristics. For example, some employees cannot correctly interpret supervisors’ intentions based on their tone of voice, gestures, or eye movements. Their execution of tasks depends on explicit instructions from the top. In contrast, others can accurately comprehend their supervisors’ unspoken messages regarding work. After studying this phenomenon in depth, scholars have defined moqi as a tacit shared understanding between two parties [

5]. Specifically, subordinate moqi is a tacit understanding of supervisors’ work-related requirements, expectations, and intentions [

5]. This unspoken agreement between supervisors and their followers is one of the essential factors influencing job attitudes and work performance [

6].

Drawing on the social information processing theory, Li and Zheng [

7] indicated that subordinate moqi has a positive effect on work engagement. However, their study focuses on illustrating how subordinates acquire and process information and neglects the role of supervisory interactions in promoting work engagement. The current study aims to fill this gap by investigating the mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX) in the moqi–engagement relationship. The leader–member exchange theory states that time and resource constraints limit the opportunities for high-quality exchanges between supervisors and employees to flourish, so supervisors can only exchange resources with selected subordinates [

8]. When employees can tacitly understand the supervisors’ true intentions, expectations, and requirements, they might be treated as insiders and secure valuable resources and support. In return, employees might be more motivated to pour their effort into work [

9]. Therefore, this paper clarifies how subordinate moqi can improve work engagement from the perspective of a social exchange relationship between supervisors and followers.

At the same time, organizational factors also play a role in the cooperation between supervisors and employees. According to the organizational support theory, perceived organizational support provides employees with positive resources and the obligation to assist the organization in pursuing its goals [

10]. The support increases the chance of employees reciprocating through a higher commitment or performance [

11,

12] and is essential to construct a healthy workplace that utilizes employees’ expertise in an effective and sustainable manner [

13]. This social exchange mechanism can reveal the critical conditions under which subordinate moqi promotes the exchange quality between supervisors and employees. In addition, the organizational support theory proposes that employees believe that evaluations from their supervisors represent that of the organization [

14]. By associating various organizational characteristics with their supervisors, employees attribute positive leadership behaviors to the organization, thus amplifying supervisors’ support into perceived organizational support [

15]. When employees perceive their supervisors’ encouragement as the organization’s treatment, they are more likely to gain a sense of belonging [

16], developing more cooperation with their supervisors. Therefore, this study will combine perceived organizational support and supervisor organizational embodiment to clarify the boundary conditions between subordinate moqi and the leader–member exchange relationship.

Knowledge Gaps and Contributions

Management practices on the organization’s sustainable development are more likely to generate a long-term impact [

17]. This is because sustainable development not only meets the needs of the current generation but also fully considers the needs of future generations, which often revolves around the economy, ecological environment, and society. At present, the sustainability of human resources is highly prominent in the face of the dilemma between work demands and employee well-being, workplace inequalities, and ecological challenges [

18]. Therefore, only through promoting sustainable management practices can organizations achieve desired economic, environmental, and social performances [

19]. However, previous research on sustainable human resources management focused on green activities specifically for environmental and economic sustainability [

20,

21]. As a result, social sustainability has become the least explored area [

22] and the mechanism for boosting work engagement without causing enduring burnout requires further investigation.

The social aspect of sustainable development refers to working conditions within an organization that ensures employees’ thriving and safety [

23]. To support long-term human resources development, energy and work resources consumed during fulfilling work demands should be evaluated and managed. For instance, although it has been validated that job crafting can produce psychological needs satisfaction [

24], such a relentless effort could also result in the deprivation of work resources and thus hurt work engagement [

25]. Furthermore, research has shown that the consistent uncertainty that employees experience could undermine work engagement and impede the social sustainability of the organization [

26]. In contrast, resources acquired, such as a work–life balance, can alleviate stress and emotional exhaustion, contributing to the sustainable development of human resources [

27]. Hence, the employees’ reservoir of work resources is essential in predicting their ability to cope with various stressors and sustain their long-term commitment.

In the current study, subordinate moqi entails a shared contextualized understanding between supervisors and employees, and LMX represents dyadic relationships between the two. They both concur with the proposition of sustainability that involves preserving, regenerating, and developing resources in a given system [

19]. Accurately perceiving supervisors’ unspoken intentions can be considered a sustainable use of resources. It improves the communication efficiency between the two parties, since supervisors do not need to over-explain or constantly repeat their instructions. Human resources can be put to better use with meanings of salient, and yet often overlooked, cues starting to emerge during interactions. This meaning-making and sharing process in the presence of organizational support prompts regenerative exchange relationships between subordinates and their immediate supervisors, which helps employees demonstrate a stronger commitment and dedication to work without depleting their work resources. Specifically, the mutually beneficial connections embedded in LMX provide pathways to generate resources that could assist employees with confronting draining experiences at work. The positive resource-generating cycle stemming from LMX could be a critical factor in converting subordinate moqi into work engagement without harming employee performance and commitment in the long run.

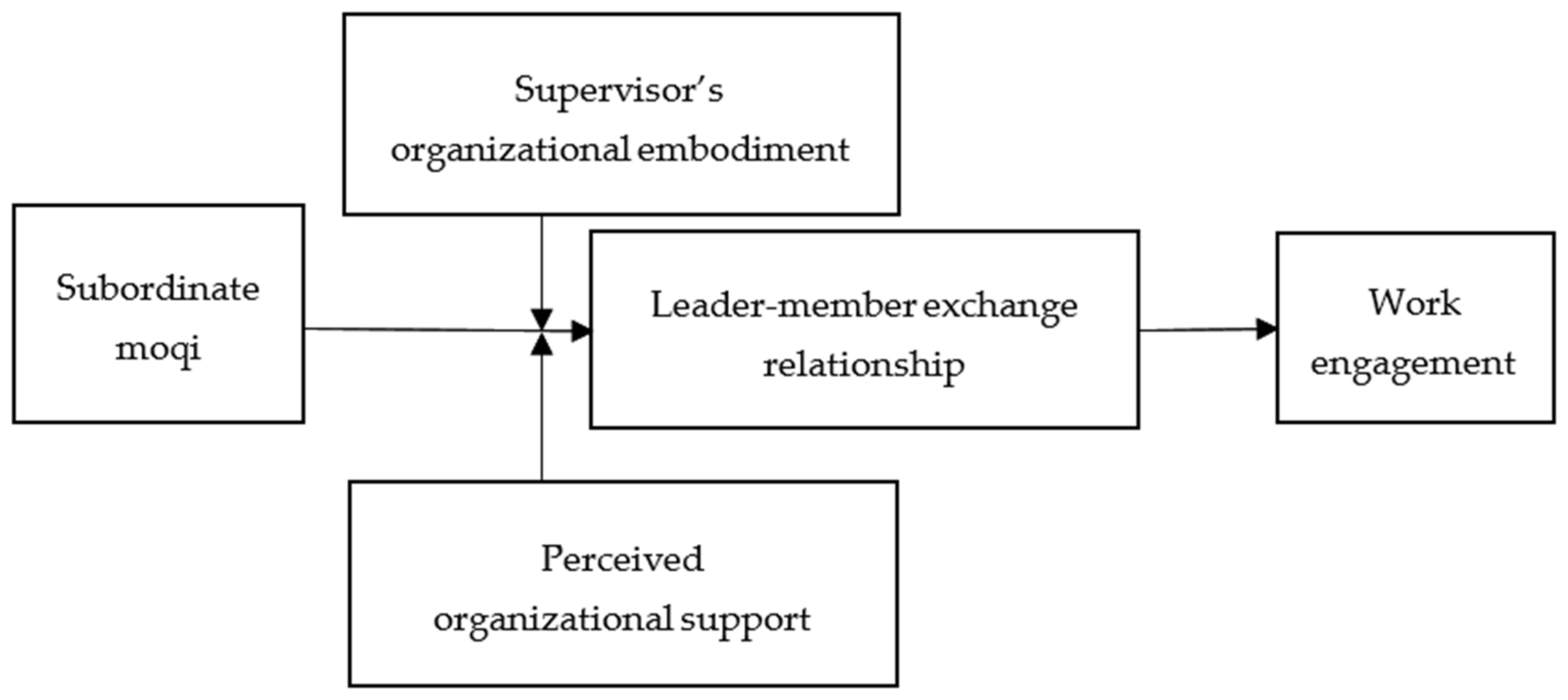

In summary, this study uses the leader–member exchange theory and the organizational support theory as the core theoretical bases to elaborate on the underlying mechanism and boundary conditions of subordinate moqi that drives work engagement. Specifically, the current study examines the mediating role of social exchanges between supervisors and followers as well as the moderating effect of supervisors’ organizational embodiment and perceived organizational support. Seeking a balance among organizations’ economic, environmental, and social performance, the researchers of this study aim to provide a new theoretical framework for the work engagement literature concerning social sustainability in the VUCA era. It incorporates employee, supervisor, and organizational factors in constructing the moqi-engagement research model that adopts resources to offset uncertainty and stress at work. Accordingly, employees can continuously contribute to the organization while maintaining their optimal value. The results can shed light on management strategies to encourage moqi-fostering and create a sustainable and responsible workplace to stimulate high personal investment. This series of human resource management practices can be valuable to the organizations’ sustainable competitive advantages.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Based on leader–member exchange theory and organizational support theory, this study introduces LMX as a mediating variable, perceived organizational support, and supervisor’s organizational embodiment as moderating variables and explores the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of subordinate moqi driving work engagement. The results show that subordinate moqi can significantly impact work engagement through employees’ mutually beneficial exchanges with their supervisors. On the one hand, an accurate interpretation of supervisors’ implicit messages demonstrates employees’ capabilities in deciphering task-related nonverbal cues and supervisors’ willingness to coordinate their thoughts with subordinates [

5]. It requires effort from both communicators to achieve shared understanding between employees and supervisors without explicit explanations. On the other hand, the findings validate that successfully decoding supervisors’ implied meanings can make employees feel valued and that they belong to supervisors’ insider groups. In this case, employees are willing to give back to their supervisors’ affirmation and support, thereby increasing their investment in work.

At the same time, employees who have cultivated moqi with their supervisors share higher qualities of exchange relationships in a supportive environment and, when supervisors have strong organizational representativeness, the sense of organizational support can elicit employees’ trust in their organizations, so they are more motivated to take advantage of nonverbal cues to facilitate relationships with their supervisors. Moreover, when the supervisor’s organizational embodiment level is high, employees are more likely to believe that supervisors’ unspoken expectations indicate the organization’s will. Driven by an acknowledgment from the organization, employees might maximize the value of their tacit understanding of supervisors’ implicit communication for promising team outcomes. Their diligence could ultimately increase the opportunities to be recognized as insiders by supervisors.

5.1. Theoretical Significance

First, this paper highlights leader–member exchange as an essential mechanism for subordinate moqi to improve work engagement. Li and Zheng’s research has examined the effect of subordinate moqi through employees’ trust in their supervisors [

7]. Based on their findings, the current study explores the impact of subordinate moqi in a bilateral approach, where contributions from supervisors and followers are necessary for moqi to take effect. With moqi fostered, employees have better chances of fulfilling performance expectations and engaging in reciprocal relationships. Previous studies have taken a subordinate-centric view on analyzing the behavior outcomes of subordinate moqi [

6,

7,

60]. In contrast, this study contributes to the literature by inspecting supervisor–subordinate interactions, which are imperative to enable the sustainable development of human resources. The results offer an understanding of the outcomes of subordinate moqi as a two-way relationship.

Secondly, this paper incorporates two situational factors, namely supervisor’s organizational embodiment and perceived organizational support, into the research framework to clarify under what circumstances the positive effect of subordinate moqi on the leader–member exchange relationship can be stronger. Interpreting supervisors’ implied meanings at all costs might not result in mutually beneficial relationships. Organizations’ and supervisors’ responsibility for sustainable and supportive practices plays a role in facilitating a positive gain spiral of deep understanding and constructive relationships. When supervisors are seen as sharing many characteristics with the organization, their instructions can be treated as the organization’s orders and can guide employees’ behaviors [

8]. Such a finding also concurs with those of Zheng [

61], who found that employees with subordinate moqi are more likely to perceive themselves as insiders if they respect power differentials. Moreover, when employees perceive strong organizational support, moqi established between employees and their supervisors in the workplace will reflect their conscious effort in processing implicit messages for the organization’s benefit. Accordingly, the current study increases the understanding of the complex dynamics between a state of shared understanding between supervisors and followers, their perception regarding the work environment, and the quality of their social exchanges. It also highlights the accountability that organizations and supervisors hold to utilize human resources responsibly or to create a healthy and resourceful work environment to stimulate employees’ dedication.

5.2. Practical Significance

As job feedback and team empowerment are two significant resources that mitigate the impact of overwhelming demands [

3], supervisors and organizations need to be aware of their role in eliciting enduring work engagement and developing social sustainability. Employees’ dedication requires regenerative support to counterbalance the threat of resource depletion. The results of this study reveal implicit means of maintaining employees’ continuing engagement at work and proposes sustainable management practices to address problems regarding communication and relationship quality with supervisors and a scarcity of work resources and support.

First, managers should equip themselves with more essential communication skills to respond positively to employees’ various requests. Such feedback offers more contextual cues for employees and ultimately benefits the cultivation of moqi. Specifically, transparent conversations disclose critical information about the rationale behind a supervisor’s actions, work style, and expressions. The additional clarity helps to unpack the undertone or the unspoken from supervisors’ verbal messages. The lack of barriers could improve employees’ accuracy in decoding nonverbal cues from their supervisors and assist them in making the best choices in semantically ambiguous situations. Therefore, managers taking the initiative to adapt their communication style lays the foundation for empowering work dynamics and positive outcomes.

Second, managers should be cautious about building strict hierarchies in the workplace. High-quality exchange relationships are critical to the growth of individuals and organizations. For instance, managers could foster a work climate filled with mutual understanding and trust so that everyone feels safe to share and collaborate. A reciprocal instead of hierarchical relationship with employees can also build acknowledgment amongst the team [

62]. The mutuality stemming from social exchanges between managers and their employees possesses the potential to maximize benefits for both sides since it enables employees to unleash their potential without damaging their ability to perform in the long run.

Finally, the organization must clarify the legitimacy of the supervisors’ power to reinforce their influence. Representing an organization creates role models for employees, so ensuring an alignment of manager and organizational values is salient to consolidate managers’ credibility. In addition, optimizing employees’ perception of a supportive environment could benefit organizational members to experience the positive effect of moqi. Organizations should emphasize offering their employees individualized benefits, development opportunities, and assistance services [

63].

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

This study also has some limitations. First, in exploring the boundary mechanism between subordinate moqi and work engagement, this study only considers employees’ subjective perceptions, such as supervisor’s organizational embodiment and perceived organizational support. Objective factors in the organization can also potentially impact the moqi–engagement relationship. Future studies may explore whether objective indicators such as promotion opportunities [

64] or job design [

65] interact with subordinate moqi. In addition, scholars have highlighted the need to examine supervisors’ perceptions of LMX relationships [

66]. Since moqi can only be fostered when both parties engage in a shared contextualized understanding [

67], examining the role of supervisors’ perception of their exchange relationships might be necessary.

Second, the research sample in this study was drawn from China, so the generalizability of these results to other cultural contexts remains ambiguous. The concept of moqi was initially proposed based on the Chinese cultural context that is often characterized by high context, high power distance, and face consciousness [

5]. Scholars should extend the findings of this study to other cultural contexts in the future.