Abstract

Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are critical pieces of climate change communication. #FridaysForFuture (FFF) is one of the movements with the most coverage. This paper analyzes the network structure generated in Twitter by the interactions created by its users about the 23 September 2022 demonstrations, locates the most relevant users in the conversation based on multiple measures of intermediation and centrality of Social Network Analysis (SNA), identifies the most important topics of conversation regarding the #FridaysForFuture movement, and checks if the use of audio-visual content or links associated with the messages have a direct influence on the engagement. The NodeXL pro program was used for data collection and the different structures were represented using the Social Network Analysis method (SNA). Thanks to this methodology, the most relevant centrality measures were calculated: eigenvector centrality, betweenness centrality as relative measures, and the levels of indegree and outdegree as absolute measures. The network generated by the hashtag #FridaysforFuture consisted of a total of 12,136 users, who interacted on a total of 37,007 occasions. The type of action on the Twitter social network was distributed in five categories: 16,420 retweets, 14,866 mentions in retweets, 3151 mentions, 1584 tweets, and 986 replies. It is concluded that the number of communities is large and geographically distributed around the world, and the most successful accounts are so because of their relevance to those communities; the action of bots is tangible and is not demonized by the platform; some users can achieve virality without being influencers; the three languages that stood out are English, French, and German; and climate activism generates more engagement from users than the usual Twitter engagement average.

1. Introduction

Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are critical pieces of climate change communication, which has grown in social media in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3,4]. In addition to human losses, the coronavirus crisis has brought to the surface a new climate awareness [5,6]. Part of the scientific community and the public believe that this virus may have interfered with animal habitats unexplored by human beings and that we must prepare for similar pandemics in the future [7,8,9,10,11]. These ideas, together with this new climate awareness, are going viral on social networks.

#FridaysForFuture (FFF) is one of the climate movements with the most social and media coverage. Although it was founded before the pandemic, in August 2018, its growth has been accentuated in the aftermath of the health crisis. It began with the demonstration by Greta Thunberg, then 15 years old, and other young activists, who sat in front of the Swedish Parliament for three weeks. Their messages and photos to call for action to curb climate change reached around the world, thanks to Twitter and Instagram [12,13]. Today, #FridaysForFuture (FFF) claims to be present in more than 7500 cities, with over 14 million followers, on 5 continents [14]. According to their manifesto, their main objective is to put moral pressure on policymakers around the world, so that they listen to scientists and adopt measures to limit global warming [14]. They declare themselves as an independent, non-political, and non-profit organization [14].

FFF stands out for being a student movement, founded by very young activists and for the same reason, focused on the centennial or Generation Z audience (born between 1994 and 2010) and the alpha audience (born from 2011 onwards) [15,16]. Considering that these two generations are digital natives, social networks are indispensable in their interpersonal and group communication [17,18]. Studies analyzing social networks as a lever for climate change are a growing area and due to the number of FFF followers and their international expansion, it is essential to study their positioning and digital communication [1,2,3].

In 2022, the social networks with the most users worldwide are estimated to be Facebook (2.91 billion users), YouTube (2.562 billion), WhatsApp (2 billion), Instagram (1.478 billion), WeChat (1.263 billion), TikTok (1 billion), and Facebook Messenger (998 million) [15]. Twitter ranks fifteenth, with approximately 436 million users worldwide, but it is still considered the social network of political activism par excellence. Communication studies describe it as the network that democratizes political communication and makes the citizen agenda become the political agenda and the agenda of the media [19,20,21,22].

Academic studies agree that Barack Obama’s election campaign in the United States in 2008 marked the beginning of a new form of political and social virality in social networks. Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter helped to mobilize the votes of women, African Americans, Latinos, and young people, previously disadvantaged and invisible sectors [23]. These networks broadened the range of issues on the public agenda, including the call for climate awareness. From there, the microblogging network has attracted users who disseminate more social content [1,24,25], who are more sensitive to addressing and denouncing social issues [3,23,26], and who are more aware of the need for climate change.

By democratizing messages, any user can go viral and become an influencer. Hashtags allow this viralization and their author does not have to have a large community of followers to achieve penetration and engagement [27,28,29]. Twitter activism has also democratized and expanded the concept of opinion leaders, who can transmit information and messages that will influence others [21,30]. Similarly, Twitter and social networks include an important affective dimension, as their spaces allow for parasocial interaction with large-scale emotional contagion [31]. The Twitter user emerges as a new prosumer paradigm [2,3], decentralizes the generation of opinion, and empowers adolescents and young adults as protagonists and leaders of a new communication for climate change [3,32]. In today’s world, the success of any global movement must be understood as an interaction between the global and the local, between virtual social networks and the processes of individual and group interaction [23,33].

The latest example can be found in the demonstrations that FFF called for on 23 September 2022, in cities around the world. According to the organization’s name, that Friday was the ultimate global call for awareness. The objective of the global strikes and demonstrations was to demand a global change from all governments, to put people, bodies, territories, and the Earth at the center of the world, with democratic access to energy, understood as a right and not as a privilege [14]. In addition to the media coverage received, the movement became a trending topic on Twitter and other social networks, thanks to its various hashtags: #FridaysForFuture, #climatechange, #climatestrike, #climate, #climatecrisis, #climatejustice, among others.

Because of the above, this article attempts to answer the following research questions:

- What are the characteristics of the social network Twitter in the days before and after the 23 September 2022 demonstration of the international youth movement #FridaysForFuture concerning its size, connection, number of members, or number of communities that form it?

- Who are the opinion leaders in the conversation generated?

- What are the topics of conversation that most interest Twitter users for the #FridaysForFuture movement?

- Is there any relationship between the format of the tweet and the engagement generated?

The above research questions will lead to the achievement of the following objectives, set out in this work, to achieve original results that can be extrapolated to other social networks and forms of communication that raise awareness about the climate:

- To analyze the network structure generated in the social network Twitter by the interactions generated by its users about the 23 September 2022, demonstration of the international youth movement #FridaysForFuture.

- To locate the most relevant users in the conversation based on multiple measures of intermediation and centrality of Social Network Analysis (SNA).

- To identify the most important topics of conversation that generated the most prominence for users of the social network Twitter regarding the #FridaysForFuture movement.

- To check if the use of audio-visual content or links associated with the messages have a direct influence on the engagement obtained.

2. Materials and Methods

The NodeXL pro program [34,35,36,37] was used for data collection. This tool was used to download, on 26 September 2022, the tweets and interactions generated from 19 September to 25 September 2022. In this way, the days before and days after the world demonstration on 23 September 2022, organized by FridaysForFuture, are analyzed. For the filtering of the tweets that made up the sample, the messages that included the hashtag #FridaysforFuture were selected. Being a globally used label, this is a global study in which no geographical limitations were established. The selected period covers the week of September in which the event took place. Likewise, the official profile of the event organizer, @Fridays4Future, began with the dissemination of the event on 20 September 2022 [14]. Thus, the days leading up to and following the global event on 23 September 2022 are analyzed.

Gephi [38] was used for the elaboration of the node network. This is an open-source software for graph and network analysis. This tool uses a 3D rendering engine to display large networks in real-time and accelerate exploration. It maintains a flexible, multi-tasking architecture and provides new possibilities for working with complex datasets and producing valuable visual results.

After data collection, the different structures were represented using the Social Network Analysis method (SNA) [39,40,41,42,43,44]. This methodology is used for the analysis of the relationships that occur between the different users or nodes, represented by the internet users who posted a tweet under the hashtag #FridaysforFuture.

It is a field of study in which several disciplines participate to study how different social phenomena are shaped, among others, behavioral sciences, statistics, computation, or mathematics [45,46,47,48]. The interdisciplinary nature of SNA has favored its popularization as a methodology in different fields of study. However, it should be remembered that the central object of SNA is the study of social relationships and how they are affected by the behavior of subjects or groups, which leads to the identification of relational structures [48]. For a better understanding, the methodology is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detail of the tools used for the application of the methodology.

Thanks to this methodology, the most relevant centrality measures were calculated: eigenvector centrality (relative importance of the user by interactions received, centered on the quality of these relationships), betweenness centrality (a user’s intermediation index, centered on the connection between users) as relative measures and the levels of indegree (number of incoming mentions that affect the user) and outdegree (number of outgoing mentions made by the user) as absolute measures.

The OpenOrd algorithm [49] has been used to represent the network of nodes in Gephi. This algorithm employs a method where large graph layouts are obtained that incorporate both local and global structures. Specifically, nodes are clustered using a force-directed design and link clustering. The clustered vertices are redrawn and the process is repeated. Finally, when a suitable drawing of the network is obtained, the algorithm is reversed to obtain a drawing of the original network.

For the discovery of communities or groups of users with similar characteristics, the Clauset–Newman–Moore algorithm was used [50,51]. This algorithm uncovers communities within a network based on a topology that works by optimizing modularity. To do so, it calculates the difference between the number of existing links in clusters and the expected number of links in an equivalent random network [45,46,47,52].

To understand the most frequently used topics of conversation, the most frequently used terms and how they interact with each other were analyzed. To do this, a count of the words and word pairs (two terms that appear in the same message) in the volume of tweets downloaded was carried out. After this, the lexical analysis of the most relevant issues within the network was completed with the preparation of a graph in which the nodes were the words and the edges were two words that appeared in the same message.

To calculate the interaction rate or engagement rate, we used the formula engagement = (number of interactions/number of followers) × 100 [6,53,54,55]. In this way, it is possible to determine to what extent each tweet generates some type of reaction from its recipients in a weighted manner [56].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of the Node Network

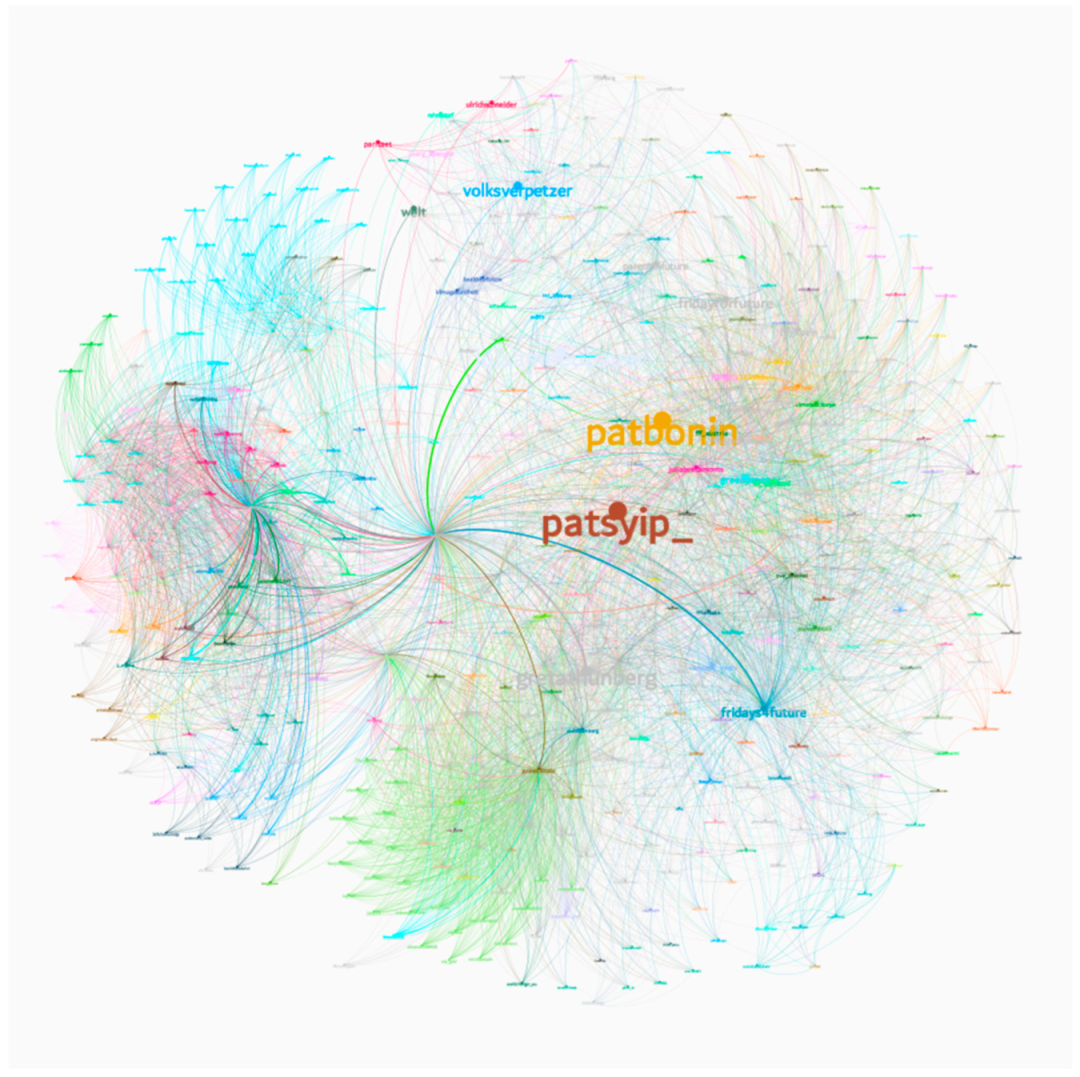

The network generated by the hashtag #FridaysforFuture consisted of a total of 12,136 users, who interacted on a total of 37,007 occasions. Of the total number of interactions, 25,581 times was a single interaction (user A interacts only once with user B) and 11,426 times was a duplicate interaction (user A interacts with user B on more than one occasion) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A network of nodes was generated under the hashtag #FridaysforFuture on Twitter. Source: own elaboration.

The type of action on the Twitter social network was distributed in five categories, with 16,420 retweets, 14,866 mentions in retweets, 3151 mentions, 1584 tweets and 986 replies. Although the volume of mentions in retweets is high, it is the indicator of the volume of replies that determines the level of conversation that takes place among users. It is perceived, as in other research, that Twitter is configured more as a network for the dissemination of messages, where acceptance is received through retweets or likes or acceptance or rejection through mentions in retweets than for debate [45,46,47,57].

The rate of reciprocity between users (number of times users interact with each other) is 0.64% and the rate of reciprocity between interactions (number of interactions that are correlated) is 1.28%. Both indicators reflect that there is hardly any conversation among users, as less than 1 out of every 100 users reacts to the interactions received.

Only 237 independent and unrelated users coexisted in the network. The clustering algorithm used detected 444 user communities. These clusters present very disparate numbers in terms of the volume of components that represent them: the first five communities have more than 1400 users, the sixth with more than 950 users, and the seventh with only 290 users. The community in 13th place, by the number of users, has fewer than 100 tweeters (70) and 400 of them have 10 or fewer users.

Among the five user communities with the highest volume of components, it is striking that the first of these, made up of 2028 users, has such a high volume of self-loops (when a user interacts with himself/herself, called autobucle) (648). This is due, as we will see below, to the user @fffbot1, who is in charge of retweeting all messages under the hashtag #FridaysforFuture. As a result, it generates a higher duplicity in interactions, adding up to a total volume of 11,631 (4541 duplicated). Finally, the maximum geodesic distance (intermediate users through which one must pass to connect the two farthest users in the network) [41] was 10 while the average geodesic distance was 3.54.

3.2. Centrality Measures

With the calculation of the centrality measures, the most important users in the conversation generated around the hashtag #FridaysforFuture were recognized. Table 2 shows the most relevant users for being among the ten with the highest values in any of the centrality measures analyzed:

Table 2.

Most relevant users within the #FridaysForFuture network on Twitter.

From this, Table 3 shows the indices of the centrality measures for the ten users with the highest values in each of them, ordered in decreasing order.

Table 3.

Ten users with higher indices of each centrality measure.

The most relevant user in the network was the @fffbot1 bot, with an index of 0.487. It is identified as the most important in a prominent way concerning the rest, which presents levels three-tenths lower. This bot has marked in its Twitter bio “I retweet the tweets with #FridaysForFuture” and points out that it is automated by the user @amity_ak97, a young man located in Nepal. This bot totals more than 300,000 retweets since its creation in February 2021. Its automated activity on the network made it a user with a fundamental role in the conversation, with an intermediation index of 82,281,168,106 among the 12,316 users of the network and an outdegree of 2048. This bot has been the link between different users of the network who would not have been in contact without the presence of this account.

This type of user is more frequent than one might imagine. Recently, in the middle of the process of buying the social network, Elon Musk put the number of fake or automated accounts at 20% [57]. Some reports from companies in the social networking sector indicate that this figure could be around 11% [58]. Twitter, for its part, published a statement saying that the number of bots on its social network barely reaches 5% of its more than 345 million users [59].

In second place is the activist Greta Thunberg (0.158), who has more than 5 million followers and is the visible image of the youth movements for the fight against climate change and, specifically, of FridaysForFuture. The young Swedish activist is one of the great opinion leaders of the conversation, maintaining high rates of intermediation (7,409,283,407) and indegree (635).

Regarding mentions received (indegree), the user @Patsyip_ was the most relevant in the Twitter conversation during the week of 19 September 2022, receiving the most mentions (1650). This young woman has just 6600 followers on the social network; despite this, she managed to be the user who received the most interactions throughout the entire week. Patsy can be seen on numerous occasions in the videos of the official profile of the Fridays For Future movement. At just 20 years old, she has become a world opinion leader on environmental and climate change issues.

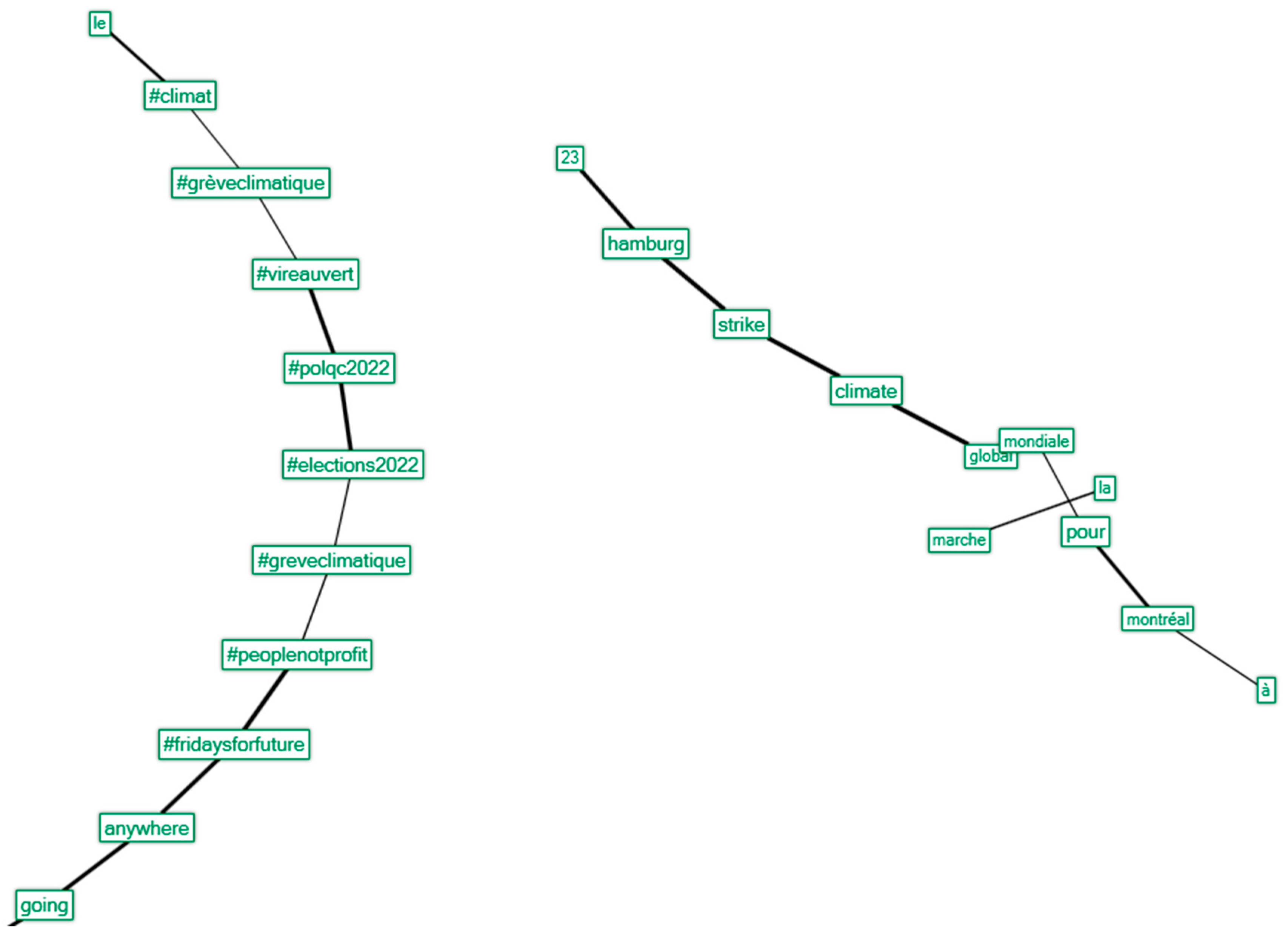

3.3. Frequency of Words and Word Pairs

The graph generated by the pairs of words that appeared most frequently in the tweets of the entire network in general presents, as the most relevant topic, the demonstrations held on Friday, 23 September 2022, in all cities around the world. It is observed how the use of alternative hashtags accompanying #FridaysForFuture has been very common. Among others, the most used were: #peoplenotprofit (5505); #elections2022 (1659); #greveclimatique (1656); #vireauvert (1654) and #polqc2022 (1654). It is also reflected how the use of different languages (English, French, German) makes this international movement reach as many countries as possible and thus, tries to mobilize more young people (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Words and word pairs that have appeared most often in the tweets. Reflects in larger size the most repeated words and with wider edges the pairs of words that have been most repeated. The left-hand side shows the most used tags, and the right-hand side shows the most used words in the tweets. Source: own elaboration.

3.4. Description of Engagement in the Analyzed Tweets

When the average engagement or sentiment rate of the tweets was analyzed, it was very high (M = 11.22%; SD = 58.55%). It should not be forgotten that the average engagement of Twitter is 0.05%, while that of Facebook is 0.13% [60]. Although the mean value is high, checking the median engagement (0.91%) and the mode (0%) reflects that there are a few tweets with a very high engagement rate, which makes these mean values higher than the average engagement. The median value indicates that at least half of the publications have an engagement rate lower than 0.91% and the mode reflects that the most repeated value is 0 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Tweet dissemination and engagement rates.

If we analyze the publications with the highest engagement, we can see that all of them are related to the demonstration on Friday, 23 September. In several of them, different activist leaders such as Greta Thunberg can be seen carrying posters and proclamations in defense of the climate. The average and the median number of retweets is striking, and this is due to the prominence of the @fffbot1 bot in the whole conversation. This causes many of the tweets to be disseminated and extended to a larger number of people, thus increasing the median and mean of the messages issued in the conversation, as shown in Table 4.

4. Conclusions

This paper divides its conclusions according to the above-mentioned objectives:

- What are the characteristics of the social network Twitter in the days before and after the 23 September 2022 demonstration of the international youth movement #FridaysForFuture concerning its size, connection, number of members, or number of communities that form it?

The results show a core group of 2028 influencers, who publicized their tweets, especially through self-loops. The most repeated activity is retweeting, followed by mentions in retweets. However, retweets do not ensure success, as it is the indicator of the volume of replies that determines the level of conversation that takes place between users. The research has also determined that the rate of reciprocity between users (number of times users interact with each other) is 0.64% and the rate of reciprocity between interactions (number of interactions that are correlated) is 1.28%. However, these 2028 influencers are spread across 444 communities and only 237 of them tweet independently of a community. It is concluded that the number of communities is large, and geographically distributed around the world, and the most successful accounts are so because of their relevance to those communities.

- 2.

- Who are the opinion leaders in the conversation generated?

According to the results, the most influential tweeter is a bot, @fffbot1, which retweets all messages under the hashtag #FridaysforFuture. As a result, it generates a higher duplicity in interactions, adding up to a total volume of 11,631 (4541 duplicates). The next four most influential influencers after the bot are personal accounts with their names: Greta Thunberg, Dawn Rose Turner, Patsy Islam-Parsons, and Patrick Bonin. Thunberg has been globally known since 2018, when she was only 15 years old and spoke out before Sweden’s general election. However, it is striking that the people who follow her on the most influential list do not have such a large number of followers and yet have achieved such virality. Turner, for example, has more than 6000 followers from Canada; Islam-Parsons, who is Australian-born but lives in Germany, also has 6500 followers; and Bonin, who is responsible for Greenpeace’s campaigns in Montreal and has 10,000 followers, is the user with the most followers, still far from Thunberg’s 4.9 million followers. The conclusion is that the action of bots is tangible and is not demonized by the platform, and some users can achieve virality without being influencers.

- 3.

- What are the topics of conversation that most interest Twitter users for the #FridaysForFuture movement?

The results showed that the tweets focused on the 23 September demonstration were the most successful and had the greatest impact. They publicized the event in the 23 cities around the world where it was being held and three languages stood out: English, French, and German. It is striking that Spanish, despite being the second most spoken language, does not appear in the top three; and that in alternative tags, the hashtag #peoplenotprofit (5505 tweets), appears in a third of the tweets studied.

- 4.

- Is there any relationship between the format of the tweet and the engagement generated?

The average engagement or sentiment rate of tweets is very high (11.22%) and much higher than Twitter’s average engagement (0.05%). However, the median engagement check (0.91%) reflects that there are few tweets with a very high engagement rate. On the other hand, if we analyze the posts with the highest engagement, we see that all of them are related to the demonstration on Friday 23 September; and posts showing activist leaders, such as Thunberg, sticking up posters or speaking to groups of people are the most popular. We conclude that climate activism can generate, in some cases, more engagement from users than the usual Twitter engagement average. The case study did achieve this and its success would be, according to the analysis, concerning the use of successful and penetrating tweets that include photos of activists who already have a community of followers.

5. Limitations and Prospectives

Given that this work offers a multidimensional approach to social networks, it is necessary to comment on some of the limitations encountered and prospective or future avenues of research so that the scientific community can replicate this work.

The first limitation was that of hashtags. It was necessary to limit the study corpus to fit the space of one research, but it is understood that in future works it would be very suggestive to make a comparison of the same hashtags in two or more languages. This could allow us to study their geolocation and find differences by continent, country, and culture. It would even be interesting to find out whether hashtags are more successful or not in countries with higher or lower pollution rates.

Similarly, it would be very suggestive to explore hashtags in more than one social network. As we already have the results for Twitter, it would be interesting to explore the same tags on YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok. However, it is understood that the comparison would not always be necessary as the functioning, nature, and users of these networks are quite different; and all studies focus on Twitter as the social network most focused on political communication and social debate or activism.

It would also be very interesting to use a gender approach, analyzing and discussing who the influencers are. Ecofeminism is an essential part of the climate awareness movement and the results of this work invite possible research on ecofeminism on Twitter, its influencers, its hashtags and, in short, its virality or keys to success.

Likewise, as this research deals with empirical phenomena, this work aims to open up future avenues of work for sectors other than academia or the scientific community. The results presented here can humbly help civil society organizations, policymakers, social media companies, and any other agent or actor who wants to work on and improve climate activism. For civil society organizations, we have shared possible formulas for successful viralization on Twitter and features of how their communication could be more effective. For political decision-makers and their parties, we discussed how climate activism penetrates the public agenda through digital agents and influencers, without coinciding with the news on the media agenda. For social networks, we have detected types of publications that achieved more engagement or virality. As with all scientific work, there must be a transfer of knowledge to society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-H.; methodology, J.R.-H.; software, J.R.-H.; validation, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; formal analysis, J.R.-H.; investigation, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; resources, G.P.-C.; data curation, J.R.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; writing—review and editing, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; visualization, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; supervision, G.P.-C. and J.R.-H.; project administration, G.P.-C.; funding acquisition, G.P.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Madrid Government (Comunidad de Madrid-Spain) under the Multiannual Agreement with Universidad Complutense de Madrid in the line Research Incentive for Young PhDs, in the context of the V PRICIT (Regional Programme of Research and Technological Innovation). Call PR/27/21. Title: “Traceability, Transparency and Access to Information: Study and Analysis of the dynamics and trends in the area”. Reference: PR27/21-017. Duration: 2022–2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Caldevilla-Domínguez, D.; Barrientos-Báez, A.; Padilla-Castillo, G. Twitter as a Tool for Citizen Education and Sustainable Cities after COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Cornelio, G.; Ardèvol, E.; Martorell, S. Estilo de vida, activismo y consumo en influencers medioambientales en Instagram. Obra Digit. Rev. De Comun. 2021, 21, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Castillo, G.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Sustainability in TikTok after COVID-19. Viral influencers in Spanish and their micro-actions. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 2022, 28, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, R.; Law, L. Building community (gardens) on university campuses: Masterplanning green-infrastructure for a post-COVID moment. Landsc. Res. 2022, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoli, A.; Probst, T.M. COVID-19 moral disengagement and prevention behaviors: The impact of perceived workplace COVID-19 safety climate and employee job insecurity. Saf. Sci. 2022, 150, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocatta, G.; Allen, K.; Beyer, K. Towards a conceptual framework for place-responsive climate-health communication. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 7, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, J.P.; Dawa, N.; Bhatia, R. Health System Response to COVID-19 and Future Pandemics. J. Health Manag. 2020, 22, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Wong, P.K. Advances in Viral Diagnostic Technologies for Combating COVID-19 and Future Pandemics. Slas Technol. Transl. Life Sci. Innov. 2020, 25, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, M.; Fixsen, D.; Schultes, M.-T.; Van Dyke, M. Using Implementation Teams to Inform a More Effective Response to Future Pandemics. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.S.; Aronowitz, S.V.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Coles, S.; Dowd, J.B.; Hale, L.; Kumar, A.; Leininger, L.; Ritter, A.Z.; Simanek, A.M.; et al. Lessons Learned From Dear Pandemic, a Social Media–Based Science Communication Project Targeting the COVID-19 Infodemic. Public Health Rep. 2022, 137, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.K.D.e.; Oliveira, I.K.D.e.; Bertoncini, B.V.; Sousa, L.S.; Santos Junior, J.L. Determining the Impacts of COVID-19 on Urban Deliveries in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte Using Spatial Analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 0, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M.; Axon, S.; Sovacool, B.J.; Sareen, S.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D.; Axon, K. Contextualizing climate justice activism: Knowledge, emotions, motivations, and actions among climate strikers in six cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 65, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan Morgan, O.V.; Thomas, K.; McNab-Coombs, L. Envisioning healthy futures: Youth perceptions of justice-oriented environments and communities in Northern British Columbia, Canada. Health Place 2022, 76, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FridayForFuture. Available online: https://fridaysforfuture.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- We Are Social & Hootsuite. Digital. 2022. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/es/blog/2022/01/digital-2022/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Solé-Borrul, A. Qué es la Generación Alfa, la Primera que será 100% digital. BBC Mundo. 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-48284329 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Szymkowiak, A.; Melović, B.; Dabić, M.; Jeganathan, K.; Singh Kundi, G. Information technology and Gen Z: The role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windasari, N.A.; Kusumawati, N.; Larasati, N.; Puspasuci Amelia, R. Digital-only banking experience: Insights from gen Y and gen Z. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filer, T.; Fredheim, R. Sparking debate? Political deaths and Twitter discourses in Argentina and Russia. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 29, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Kim, Y.M. Equalization or normalization? Voter—candidate engagement on Twitter in the 2010 U.S. midterm elections. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2017, 14, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molefe, M.; Ngcongo, M. You Don’t Mess With Black Twitter!: An Ubuntu Approach to Understanding Militant Twitter Discourse. Communicatio. S. Afr. J. Commun. Theory Res. 2021, 47, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimbach, T.; Palmer, J. #AustraliaOnFire: Hashtag Activism and Collective Affect in the Black Summer Fires. J. Aust. Stud. 2022, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernárdez-Rodal, A.; López-Priego, N.; Padilla-Castillo, G. Culture and social mobilisation against sexual violence via Twitter: The case of the #LaManada court ruling in Spain. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2021, 79, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draege, J.B. Narrow Responses to Social Movements: Evidence from Turkey’s Gezi Protests. Representation 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A. Communication during pandemic: Who should tweet about COVID and how? J. Strateg. Mark. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congosto, M. Digital Sources: A Case Study of the Analysis of the Recovery of Historical Memory in Spain on the Social Network Twitter. Cult. Hist. Digit. J. 2018, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Planells, A. Análisis del uso de los medios por las generaciones más jóvenes. El Movimiento 15M y el Umbrella Movement. El Prof. De La Inf. 2015, 24, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shermak, J.L. Scoring Live Tweets on the Beat. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.B. Trump Trumps Baldwin? How Trump’s Tweets Transform SNL into Trump’s Strategic Advantage. J. Political Mark. 2020, 19, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno, M.; Daly, A.J.; Segado, S. Identificando a los nuevos influyentes en tiempos de Internet: Medios sociales y análisis de redes sociales. Rev. Española De Investig. Sociológicas 2016, 153, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Puche, J. Internet and emotions: New trends in an emerging field of research. Comun. Rev. Científica Iberoam. De Comun. Y Educ. 2016, 46, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Castillo, G.; Oliver-González, A.B. Instagramers and influencers. The fashion showcase of choice for young Spanish minors. ADResearch 2018, 18, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldevilla-Domínguez, D.; Rodríguez-Terceño, J.; Barrientos-Báez, A. Social unrest through new technologies: Twitter as a political tool. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 1264–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Shneiderman, B.; Smith, M.A. Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, A.; Woehle, R.; Tiemann, K. Social Network Analysis for Analyzing Groups as Complex Systems. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2012, 38, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, T. Twitter activism and youth in South Africa: The case of #RhodesMustFall. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, M.; Choe, J. #overtourism on Twitter: A social movement for change or an echo chamber? Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; pp. 361–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman, R.A. Introducción a los Métodos del Análisis de Redes Sociales. Available online: http://revista-redes.rediris.es/webredes/textos/Introduc.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Molina, J.L. La ciencia de las redes. Apunt. De Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2004, 11, 36–42. Available online: http://revista-redes.rediris.es/recerca/jlm/ars/ciencia.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Sanz-Menéndez, L. Análisis de redes sociales: O cómo representar las estructuras sociales subyacentes. Apunt. De Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2003, 3, 1–10. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/1569/1/analisis_redes_sociales.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Rodríguez, J.A. Análisis Estructural y de Redes; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2005; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, A. ¿Escribía Lope de Vega con falsilla? Aproximación a El mayordomo de la duquesa de Amalfi y El perro del hortelano desde el Análisis de Redes Sociales. Bull. Span. Stud. 2021, 98, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotarelo-Esteban, L. Mujeres intelectuales españolas y sus redes sociales en el exilio estadounidense. J. Span. Cult. Stud. 2022, 23, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Polaino, R.; Martín-Cárdaba, M.; Villar-Cirujano, E. Citizen participation in Twitter: Anti-vaccine controversies in times of COVID-19. Comunicar 2021, 69, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Polaino, R.; Villar Cirujano, E. Greta Thunberg as a viral character in the tweets of the information sector during the COP25 climate summit. Rev. De Cienc. De La Comun. E Inf. 2021, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Polaino, R.; Lafuente-Pérez, P.; Luna-García, Á. Twitter as means for activism towards Climate Change during COP26. Estud. Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico 2022, 28, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Monsalve, E.G.; Gómez, H. Análisis de redes sociales como metodología de investigación. Elementos básicos y aplicación. La Sociol. En Sus Escen. 2006, 13, 1–28. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.udea.edu.co/bitstream/10495/2542/1/BrandEdinson_analisisredesmetodologiainvestigacion.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Martin, S.; Brown, W.M.; Klavans, R.; Boyack, K.W. OpenOrd: An open-source toolbox for large graph layout. SPIE Proc. 2011, 7868, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M.M. Information Diffusion in Halal Food Social Media: A Social Network Approach. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterbur, M.; Kiel, C.h. Tweeting in echo chambers? Analyzing Twitter discourse between American Jewish interest groups. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2021, 18, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar Kakhki, M.; Gargeya, V.B. Information systems for supply chain management: A systematic literature analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 5318–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sued, G.E.; Castillo-González, M.C.; Pedraza, C.; Flores-Márquez, D.; Álamo, S.; Ortiz, M.; Lugo, N.; Arroyo, R.E. Vernacular Visibility and Algorithmic Resistance in the Public Expression of Latin American Feminism. Media Int. Aust. 2022, 183, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffredi-Kähr, A.; Petrova, A.; Malär, L. Sponsorship Disclosure of Influencers—A Curse or a Blessing? J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.H.; Lyford, C. Using Social Media for More Engaged Users and Enhanced Health Communication in Diabetes Care. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 0, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornos-Inza, E. Tasa de interacción (engagement) en Twitter. Related: Marketing. 2020. Available online: https://eduardotornos.com/tasa-de-interaccion-engagement-twitter/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Asher, I. Elon Musk ahora pone condiciones para desbloquear la compra de Twitter. Business Insider España. 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/3y5Nrdj (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Kay, G.; Hays, K. Twitter asegura que Elon Musk trató de ocultar el número de cuentas falsas. Business Insider España. 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/3dTWdnT (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Frenkel, S. Todo lo que debes saber sobre los bots de Twitter, y su relación con la compra de Elon Musk. The New York Times. 2022. Available online: https://nyti.ms/3Rt0JHE (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- SocialInsider. Social Media Industry Benchmarks—Know Exactly Where You Stand in Your Market. 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/3E1UUxW (accessed on 29 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).