Abstract

How to release rural consumption potential is currently of great significance for the sustainable economic growth of the developing world. Using representative survey data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), this paper studied the impacts of mobile payments on rural household consumption and its mechanisms. This study constructed instrumental variables from the perspective of induced demand for mobile payments to overcome the endogeneity problem and found that the application of mobile payments significantly promoted rural household consumption by 29.8–52.3%. Mechanism analysis indicated that mobile payments could ease liquidity constraints, enrich consumption choice, and improve payment convenience for rural households, which are the main channels behind the above finding. Heterogeneous analysis showed that the impact of mobile payments on household consumption of the elderly and less educated was relatively higher. Moreover, this study found that mobile payments are conducive to promoting the consumption upgrading of rural households by significantly improving their enjoyment consumption. In addition, although it encourages rural households to consume more online and mobile payment methods, it does not crowd out the effect of rural households’ offline consumption. The findings of this paper provide new insight into the role of technical progress in promoting total consumption and consumption upgrading in rural areas.

1. Introduction

By the end of 2019, the rural population around the world had reached 3.42 billion, accounting for 44.3% of the total population, and is mainly concentrated in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Data source: UN FAO Database). In recent years, population aging and other problems have led to insufficient consumption in developing countries in Asia [1], which is one of the crucial reasons for restricting domestic economic growth [2]. In 2019, the average monthly consumption of rural residents in Indonesia was only CNY 62. The consumption of rural residents in China is CNY 207 per month, but it is still less than half of the consumption of urban residents in China. Due to the slow marketization process and the low degree of trade liberalization, the domestic consumer market demand in developing countries is weak [3]. Meanwhile, the imperfect development of the financial market in rural areas aggravates the credit constraints of rural residents [4,5]. These problems have seriously restricted the rural residents’ willingness to consume. How to release rural consumption potential is currently of great significance for the economic growth of the developing world. This study attempts to determine whether mobile payments, an emerging digital technology which plays a crucial role in the digital economy, can improve rural household consumption in China.

Since the 1990s, the global development of information technology has brought innovation in payment methods. Among them, mobile payments are a new mode of payment implemented by mobile devices, which is a combination of the Internet, terminal devices, and financial institutions. Previous studies pointed out that, compared with a traditional cash transaction, mobile payments improve consumption convenience and expand the consumption range [6,7], which is conducive to risk sharing and reduces the negative impact of income uncertainty [8,9]. However, its effects on residents’ consumption are less explored in the literature, particularly for rural populations.

Consequently, this study enriches the literature by empirically testing the relationship between mobile payments and rural household consumption in China. China is undergoing rapid urbanization, while its rural population is still huge. In 2020, China’s rural population was 510 million, accounting for 15% of the world’s rural population. Besides its large population, China also has the world’s largest mobile payment market in terms of user and transaction size. As of the first half of 2018, the number of mobile payment users in China was 890 million (Data source: China Mobile Payment Development Report 2019). The latest data disclosed by the People’s Bank of China indicates that non-bank payment institutions provided 274.88 billion mobile payments with a total amount of CNY 74.42 trillion to rural areas in 2018, which increased from 2017 by 112.25 and 73.48%, respectively. At the same time, the economic and financial development across regions in China is largely unbalanced, which provides enough variation to identify the impacts of mobile payments on rural household consumption.

The two works of literature that are comparatively relevant to this study are Li et al. (2020) [10] and Zhang et al. (2022) [11]. Li et al. (2020) [10] used the digital inclusive finance index developed by Peking University to investigate the impact of inclusive finance on Chinese household consumption and found that mobile payments are the main mechanism. However, they did not examine the impact of mobile payments on rural household consumption. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2022) [11] found that mobile payments significantly boosted Chinese rural household consumption and had a stronger positive impact on rural households with poor socioeconomic status. However, they did not explore the underlying mechanisms. In addition, with the treatment of endogenous problems, they selected the indicator of whether the family owns a smartphone as an instrumental variable, but this indicator cannot meet the exogenous requirements of instrumental variables because households with more smartphones may have stronger spending power rather than increased consumption through mobile payments. Therefore, using a smartphone as an instrumental variable may lead to the overestimation of regression results.

This paper fills the gap by exploring the impact of mobile payments on rural household consumption from the perspectives of average effect, mechanisms of action, and consumption structure, using nationally representative data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS). This study used “the proportion of households engaged in commodity sales using mobile payment in his/her district or county” as the instrumental variable of whether a consumer uses mobile payments to address the endogeneity problems from omitted variables and reverse causality. It is assumed that if more sellers use mobile payments to receive money, then consumers are more likely to use mobile payments to pay. Except for the payment channel, the method of receiving money from sellers could have no other effects on consumers’ consumption behavior. The estimates indicate that mobile payments significantly increase a rural household’s consumption by 29.8–52.3%. The results are valid for various robustness tests, including changing instrumental and key variable measurements and selecting samples.

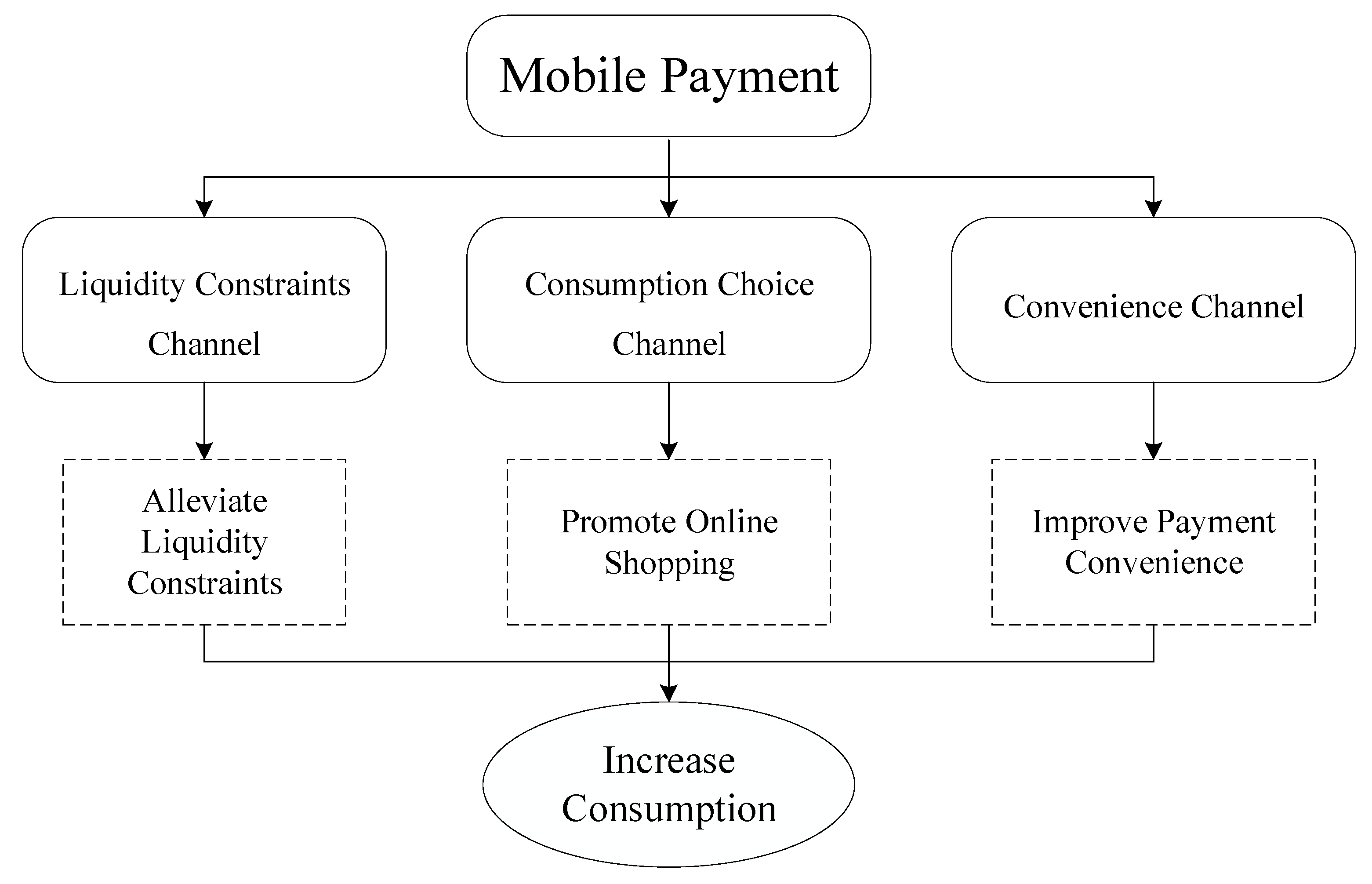

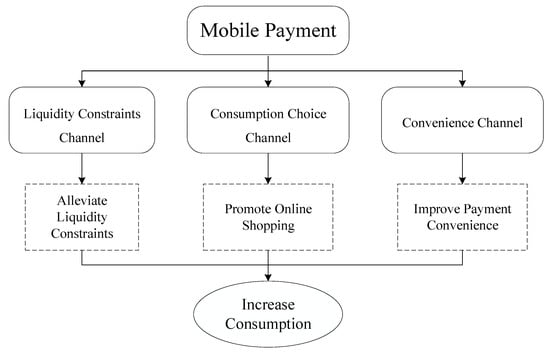

To further explore the mechanisms that underlie the established causal relationship, this paper posits three channels through which mobile payments can affect household consumption. Specifically, the first is a liquidity constraints channel where the use of mobile payments can promote consumption by easing the liquidity constraints of rural households. In this paper, the liquidity constraints of a household are measured by the ratio of liquid assets to income and the ratio of financial assets to income. The second is a consumption choice channel where the use of mobile payments can promote online shopping and thus enrich the consumption choice of a household compared with offline shopping. This study constructs two indicators to test this channel to determine whether online shopping and the proportion of online consumption are in the total consumption. The third is a convenience channel where the use of mobile payments can largely improve the convenience of payment, which is believed to promote consumption. This study tests this channel by investigating the heterogeneous effects on financial institutions in areas with different development levels. If the convenience channel acts, then areas with poor accessibility to financial institutions would benefit more from the application of mobile payments. The empirical analysis supports the existence of all three channels.

Finally, this paper examines the impact of mobile payments on the consumption structure and pattern of rural households in China. The results show that mobile payments significantly improve the enjoyment consumption of rural households, which suggests a consumption upgrade in rural China. In addition, this study finds that the application of mobile payments has significantly changed the consumption patterns of rural households in that more transactions are online and have promoted the offline consumption of rural households.

This paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, the findings of this study provide novel empirical evidence for understanding the economic effect of mobile payments. With the rapid application of mobile payments all over the world, many studies are emerging on its effects on individual economic behaviors, including entrepreneurship [12], risk-taking [6,8], and welfare [13]. Among them, Riley (2018) [6] and Jack and Suri (2014) [8] examined the impact of mobile payments on individual consumption, but they did not specifically analyze the influence mechanism. This paper focuses on the effects of mobile payments on an underconsumption group (rural residents) and examines three channels through which mobile payments affect household consumption (namely liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience channels).

Second, this work adds to the understanding of rural consumption in developing economies. Existing studies have investigated the impact on rural consumption mainly from the perspectives of income [14], precautionary saving motivation [15,16], and other economic factors. Most of the conclusions found that inadequate income and precautionary saving motivation inhibited the consumption of rural residents. This paper investigates the positive impact of a payment method on household consumption from the perspective of technological advancement.

Third, this study contributes to our understanding of the effect of digital technology on the macro-economy. In recent years, many studies have emerged on the impact of representative digital technologies, such as the Internet, e-commerce, and digital finance, on the labor market [17,18], international trade [19], and consumer consumption [20,21,22]. Mobile payments are another emerging digital technology which plays a crucial role in the digital economy. The finding on the effect and mechanisms of mobile payments on residents’ consumption of this paper adds micro-evidence for the macro-economic impact of digital technology.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature review and posits the three channels; Section 3 introduces data and empirical strategies; Section 4 reports the main results and explores the underlying mechanisms; Section 5 reports the effects on consumption structure and pattern; Section 6 concludes this study.

2. Literature Review and Mechanism Analyses

With the continuous development of the Internet and information technology, the payment methods of daily consumption are also changing. The shifting from the traditional cash payment to the new method represented by credit cards and mobile payments has significantly improved the convenience for both sellers and consumers, which is changing consumer behavior and leading extensive discussions by scholars all over the world. Most studies confirm that mobile payments can increase its users’ willingness to consume and, therefore, their total consumption. For example, Xu et al. (2019) [23] found that the application of Alipay increases the total transaction amount and frequency by about 2.4 and 23.5%, respectively, and the effect of Alipay replacing offline payment keeps strengthening over time. Using consumer data from a chain supermarket in China from 2014 to 2019, Liu and Zhang (2019) [24] found that the offline consumption amount and frequency of consumers using mobile payments have significantly increased. Based on an experiment design, Liu et al. (2020) [25] found that mobile payments effectively save shopping time compared with cash payments and that mobile payments can mitigate the negative impacts of COVID-19 on Chinese household consumption using data from the China Household Finance Survey in the first quarter of 2020.

As for the mechanisms of mobile payments affecting household consumption, the existing literature mainly discusses it from the perspective of easing liquidity constraints and reducing shopping costs, but there is still a lack of systematic discussion. This paper combines the existing literature on the influencing factors of household consumption and discussions on the impact of mobile payments on household consumption behavior, and provides a further discussion on the effects of mobile payments on household consumption from three channels: liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience.

First, the liquidity constraints channel refers to the fact that mobile payments can ease households’ liquidity constraints by improving their access to financial services, thus stimulating their consumption. According to the life cycle theory, rational consumers will make consumption choices not only according to their current income but also considering their income in the future and realize the maximum consumption utility through saving and borrowing [26]. In fact, due to the imperfect employment security and financial market in China, residents often face high uncertainty in terms of employment, income, housing, education, and other aspects [27,28,29]. This increases households’ incentive to save preventatively and reduces their willingness to consume, generating a liquidity constraint problem. Borrowing is the main way for households to ease liquidity constraints, but the formal borrowing review process in China’s credit market is cumbersome and lengthy. Comparatively, using mobile payments can improve the possibility of rural households obtaining financial services [30]. Specifically, when using mobile payments for credit, consumers do not need a physical mortgage and can choose an installment payment with low interest, which means that consumers can smoothly transit to the next consumption only with a relatively low cost to realize the maximum consumption utility. In addition, some Fintech enterprises also encourage consumers to use mobile payments by providing targeted consumer credit preferential facilities, such as Alibaba’s Ant Check Later and JD Finance’s JD Baitiao. Therefore, we posit that the application of mobile payments can promote consumption by easing households’ liquidity constraints.

Second, the consumption choice channel refers to the fact that mobile payments promote the development of online shopping, which can expand the range of consumption choices for households, thus enhancing their consumption demand. According to the “search cost theory,” consumers need cost to obtain market price and product quality information. If there are effective media to reduce the search cost for consumers, market efficiency will be improved. When consumers are faced with products with higher prices, they may make greater efforts to search for products to obtain more information [31]. Obviously, compared with urban areas, rural areas have lower population densities and less developed services, which leads to higher search costs for rural residents. This results in great limitations and information asymmetry for rural residents in their consumption choices. In the choice of consumption, rural residents generally rely on farmer’s markets to meet their daily consumption needs. However, if there is a great consumption demand, such as large household appliances, rural residents often need to go to the shopping malls in nearby towns, which undoubtedly increases their search costs. The use of mobile payments enables these households to meet their shopping needs through online platforms, thus improving search efficiency. Moreover, the online shopping platform provides personalized and diversified products for households. People can directly use mobile payment devices to choose goods or services on the online shopping platform, which also reduces search costs and can improve residents’ willingness to consume. In addition, the popularity of online shopping reduces the level of price dispersion, making the price of some products online lower compared with offline prices [32,33], which also help to attract consumers to online shopping and improve their total consumption.

Third, compared with cash payment, the advantages of mobile payments lie in the convenience, universality, and independence of the service time [34,35], which improves the space-time constraint of traditional cash payment. The convenience channel is even more important in rural areas. On the one hand, the financial development level of rural areas is relatively low compared with urban areas, which leads to the inefficient allocation of financial resources and may inhibit the consumption demand of rural residents [36]. If there are fewer branches of financial institutions, such as banks in villages, it will increase the cost of rural residents to pay with cash, thus reducing their willingness to consume. On the other hand, the relatively backward transportation infrastructure and rainy weather in rural areas will further increase the shopping cost of rural households. Using mobile payments enables rural households to complete consumption without leaving their homes. Finally, this study illustrates the channels through which mobile payments affect household consumption in Figure 1. The total effect of mobile payments on rural household consumption is from the liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience channels.

Figure 1.

The impact channels of mobile payments on household consumption.

In addition to the three channels examined in this paper, differences in experience brought by payment methods also affect household consumption behaviors. Generally, consumers’ consumption experience depends on the difference in the product’s price and transaction cost [37]. If consumers spend a lot in the last period, it may lead to pain of payment, thus reducing consumers’ willingness to consume in the next period [38]. Different from cash payments, mobile payments can reduce the pain of payment caused by high expenditure. The reason behind this is that the use of mobile payments may bring a “mental account” effect to consumers [39]. When consumers use cash to spend, they will clearly feel the “decline” in wealth, but when they use mobile payment, they mainly use electronic money to conduct transactions, and they only feel the reduction in book number, which has a weak psychological stimulation effect. This “mental account” effect may lead to an increase in unplanned purchases.

The preceding arguments suggest a positive relationship between mobile payments and rural household consumption, which is formalized in the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Mobile payments positively influence rural household consumption through three channels, namely, liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience channels.

3. Data and Empirical Strategies

3.1. Data

The data used in this paper is from the 2017 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) conducted by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in China. The survey adopts a stratified three-stage sampling method proportional to the size of the population. The data are nationally representative. The survey covers 29 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) in China, except Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. The 2017 CHFS collected 40,011 valid samples, including 12,732 rural households. The questions covered detailed information about households’ demographics, assets and liabilities, insurance and security, and income and expenditure, which provides support for our study to investigate the impact of mobile payments on rural household consumption. First, in the part of income and expenditure, the total consumption expenditure of the family is asked in detail, and the consumption type is further asked (including online consumption). Second, compared with the Chinese Household Finance Survey in 2013 and 2015, the general payment method of family shopping was added to the questionnaire in 2017. This study dropped the household samples with household heads younger than 18 and older than 80 years old, zero total household consumption, and those whose monthly income was less than CNY 500 to ensure the robustness of the results during empirical analysis. Finally, 9828 valid samples were obtained.

3.2. Empirical Model

This paper mainly examines the impact of mobile payments on household consumption. Pursuant to the method used by Li et al. (2020) [10] and Zhang et al. (2022) [11], the empirical model constructed in this study is as follows:

The dependent variable, Consumptioni, refers to the total consumption of rural household, i. Mobilepaymenti is a dummy variable, which equals one if a household uses mobile payment tools and zero otherwise. X is a set of control variables. λp is the provincial fixed effect used to control for time-invariant provincial-level characteristics, and ε is a random error term. This study clustered standard errors at the county level to address the potential bias arising from heteroskedasticity. In Model (1), β1 is the coefficient of interest, which is expected to be positive, indicating that the use of mobile payments can increase a rural household’s consumption.

3.3. Variable

(1) Household consumption

The dependent variable in this paper is the total consumption of rural households, which is a sum of expenditure on food, clothing, rent, equipment and services, medical and healthcare consumption, transportation and communication, education and entertainment, and other goods. In this paper, consumption is further divided into subsistence consumption, development consumption, and enjoyment consumption. Among them, subsistence consumption includes the consumption of food, clothing, and rent. Developmental consumption includes the consumption of equipment and services, healthcare, transportation, and communication. Enjoyment consumption is that of education, entertainment, and other goods.

(2) Mobile payment

Mobile payment is the core independent variable of this paper. In the CHFS, respondents are asked, “Which of the following payment methods do you and your family usually use when shopping (including online shopping)?” followed by “cash,” “credit card,” “pay by computer,” “pay by mobile terminal such as mobile phone or iPad,” and “Others.” We define the households by those who choose “pay by mobile terminal such as mobile phone or iPad” as those who use mobile payments, with Mobiliepayment equalling 1 and 0 otherwise. According to this study’s statistics, 12.6% of rural households in China used mobile payments for shopping in 2017.

(3) Control variables

The control variables in this paper are divided into three levels. First, at the householder level, the control variables include the household head’s age, sex, education (years of education of household head), marital status (married or other), physical health status (good or poor health), working status (employed or other), and risk preference (risk appetite and risk aversion). Second, household characteristics, such as household size, elderly dependency ratio, household income, poverty, and asset liability ratio, are taken into consideration because of the positive influence of family size, household income, assets, and elderly dependency ratio on household consumption. Third, at the macro level, the province’s fixed effects are controlled. Table 1 presents the summary statistics of all the variables used in this study.

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

3.4. Endogeneity and Instrumental Variable

In this paper, an empirical analysis may suffer from an endogeneity problem. First, mobile payments are one of the consumption modes of consumers. Whether to use it or not is affected by the consumption demand of a consumer. For example, a household with great consumption demands will choose to use mobile payments considering its convenience, while households with small consumption demands may use mobile payments less in order to avoid unnecessary expenses. Second, there may be unobservable factors that simultaneously affect the choice of payment method and consumption, such as the individual preference for consumption and the development level of regional information technology. Both the reverse causality and missing variables problems may lead to biased estimates.

The endogeneity problem is solved by instrumenting for mobile payments. As it is difficult to find a factor at the individual level that only affects the choice of payment method without simultaneously affecting individual consumption behavior, we turn to the demand-induced use of mobile payments. Specifically, we use “the proportion of households engaged in commodity sales using mobile payment in his/her district or county” as the instrumental variable of whether a consumer uses mobile payments. The logistic of the instrumental variable is that: First, if more local sellers use mobile payments to receive money, then consumers are more likely to use mobile payments to pay for consumption; Second, the payment method setting of the seller’s commodity has no direct relationship with the consumer’s behavior. That is to say that the instrumental variable can only affect local households’ consumption through the payment method, satisfying the exogenous requirement.

4. The Impact of Mobile Payments on Rural Household Consumption

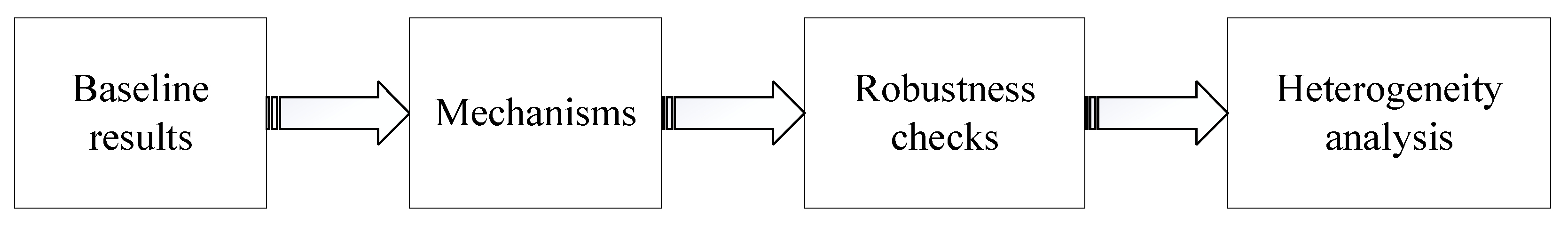

This section will report the main results and explore the underlying mechanisms. The empirical analysis is presented in Figure 2. First, the baseline regression results are shown. Second, three influencing mechanisms are tested, namely the liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience channels. Third, several robustness tests are conducted by adjusting the sample and replacing the variable measures. Finally, heterogeneity analysis is conducted to provide a full understanding of the relationship between mobile payments and rural household consumption.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the empirical results.

4.1. Baseline Results

Table 2 first reports the estimation results of Model (1). Column (1) is the OLS estimation results. After controlling for other variables, the coefficient of mobile payment is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the use of mobile payments is associated with higher household consumption. On average, the consumption of rural households that use mobile payments is about 29.8% higher than households that do not use mobile payments.

Table 2.

Mobile payments and rural household consumption.

Column (2) shows the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimates using instrumental variables. The first-stage results show that a higher proportion of households engaged in commodity sales using mobile payments in a district/county is associated with a higher probability of using mobile payments (t-value is 10.35, significant at the 1% level), which is consistent with this study’s expectation. At the same time, the F-statistic estimated in the first stage is 107.14, much greater than the critical value of 16.38, indicating that there is no weak instrumental variable problem. According to the second-stage estimation results, the impact of mobile payments on rural household consumption is still significantly positive at the significant level of 1%; however, the influence effect is significantly greater than that in the OLS estimation results, suggesting that there are unobservable factors that have a same-directional impact on mobile payment use and household consumption. The 2SLS estimates indicate that the use of mobile payments can significantly increase rural household consumption by 52.3%. The main findings in Table 2 are consistent with Li et al. (2020) [10] and Zhang et al. (2022) [11] and indicate that, compared to traditional cash payment, the application of mobile payments can promote rural household consumption by easing liquidity constraints, enriching consumption choice, or improving payment convenience. In this regard, governments and relevant departments should actively encourage rural residents to use mobile payments, which can help improve rural household consumption levels in developing countries.

The estimations of control variables on household consumption are also consistent with previous studies. Specifically, the household heads’ age was negatively correlated with consumption, which may be caused by the precautionary saving motivation. Highly educated households have greater consumption than lesser-educated households. Marriage may supplement cash flow for households, so it increases household consumption. Unhealthy households have greater consumption than healthy households, possibly because they have to spend more on healthcare. Not having a job has a significantly negative impact on household consumption, which may be due to the unstable source of income. Household heads who prefer risks are likely to be more adventurous and thus spend more than risk-averse ones. Household size, household income, and household assets were also positively correlated with household consumption.

4.2. Mechanisms

Based on the discussion in Section 2, this paper will empirically test the three channels at work: liquidity constraints, consumption choice, and convenience.

First, to measure the liquidity constraints of a household, this paper refers to Kaplan et al. (2014) [40] to calculate the ratio of liquid assets (including savings and cash) to income. The households whose liquid assets-to-income ratios are smaller than 0.5 are defined as liquidity constrained in this paper, and then they are examined in whether their use of mobile payments improves household liquidity constraints. For robustness, following Zeldes (1998) [41], this paper defines households whose financial assets (including stocks, funds, bonds and insurance, etc.) are less than two months’ income as liquidity constrained. The regression results are shown in Table 3; Columns (1) and (3) report the OLS estimation results, and columns (2) and (4) report the 2SLS estimation results. In all four regressions, the coefficients of interest are significantly negative, suggesting that the use of mobile payments can significantly reduce household liquidity constraints, confirming the existence of the liquidity constraints channel.

Table 3.

Liquidity constraints channel.

Second, this study tests the consumption choice channel by investigating the effect of mobile payments on a household’s online shopping behavior. The CHFS asked rural households whether they shop online, where the question in the questionnaire was “Has your family ever shopped online? 1. Yes; 2. No.” and their online consumption in the last year, where the question in the questionnaire was “How much money did you spend on online shopping last year? (If you did not buy online last year, fill in 0)”. According to the answers, this study constructed two indicators of whether rural households use online shopping and the share of online shopping consumption in total consumption. The regression results are shown in Table 4; In Columns (1) and (2), we find that rural households who use mobile payments are more likely to choose online shopping, with a probability about 55.1–79.3% higher than those who do not use mobile payments. The results in Columns (3) and (4) further show that the use of mobile payments may increase the share of online shopping consumption in the total consumption of rural households by 1.5−2.9 times. The results in Table 4 indicate the existence of the consumption choice channel.

Table 4.

Consumption choice channel.

Finally, this paper tests the convenience channel by investigating the heterogeneous effect of mobile payments on the development of financial institutions. Some studies have pointed out that low financial development will inhibit the consumption demand of residents [36], so it is expected that in areas with lower financial development, the application of mobile payments can stimulate more local consumption. This study uses the financial industry marketization index calculated by Wang et al. (2019) [42] to measure the level of financial development of a county and divides all the counties into two groups according to the mean value of the index. The index includes two secondary indicators: the proportion of total assets of financial institutions other than banks to total assets of all financial institutions and the proportion of liabilities of non-state firms to total firms’ liabilities. Table 5 reports the sub-sample regression results. In both groups, the application of mobile payments can significantly increase consumption in rural households, implying the existence of other channels, such as the liquidity constraints channel and consumption choice channel. Moreover, we find the effects are much higher in counties with lower financial development (0.65) than in counties with higher financial development (0.45), which support this study’s hypothesis and confirm the convenience channel.

Table 5.

Convenience channel.

4.3. Robustness Checks

(1) Using different instrument variables

Following the ideas from previous studies, this study uses another two instrumental variables to address the endogeneity problem: the connection rate of broadband in the community where the household lives and the proportion of households in the community that use mobile payments except for themselves. These two instrumental variables naturally satisfy the requirement of the correlation condition of the instrumental variable. First, a higher broadband connection rate in the community means a household is more likely to use mobile payments. Second, whether rural households use mobile payments may also be influenced by the behavior of their neighborhoods. Table 6 reports the results of this robustness test. The promotion effect of mobile payments on rural household consumption is still established using different instrumental variables.

Table 6.

Robustness check: alternative instrumental variables.

However, one thing that needs to be noted here is that, compared with the instrumental variables used in this paper, these two instrumental variables are deficient in meeting the exogenous conditions. First, the use of broadband not only affects a household’s choice to use mobile payments but also directly affects their consumption behavior by reducing transaction costs or other channels. Second, although the neighborhood’s mobile payment use is not directly associated with their consumption, it reflects a specific preference of the neighborhood, which could be related to the consumption preference of the neighborhood and thus affect the household’s consumption behavior.

(2) Adjusting the household sample

This paper conducted three tests on the robustness of sample selection. First, the samples that chose “pay by computer” but did not choose “pay by mobile phone, iPad and other mobile terminals” were excluded from the control group. Compared with traditional cash payments, payment by computer is similar to mobile payments in many aspects, such as the liquidity constraints and convenience channels highlighted in this paper. Taking these samples as the control group will lead to a small estimate of the consumption effect of mobile payments. Second, considering the fact that household size may have some impact on the consumption decision of a household, this paper followed the existing study [29] and dropped the samples with a population greater than eight. Third, to mitigate the influence of extreme values on estimation results, this paper replaced the household consumption that was beyond the 1 and 99% quantiles of the whole sample with the corresponding tailing value. Table 7 presents the results with different samples; this paper found that both the magnitudes and significance of the coefficient of interest under OLS and 2SLS estimations are nearly unchanged compared with the main results, which suggests the robustness of this study’s findings to the sample selection issue.

Table 7.

Robustness check: different household sample.

(3) Changing consumption measurement

This paper also uses two different consumption measurements, namely per capita household consumption and consumption-to-income ratio, as the independent variables to conduct the empirical analysis. The results are shown in Table 8. With different consumption measurements, this study finds a consistent and robust effect of mobile payment applications on rural household consumption.

Table 8.

Robustness check: alternative consumption measurement.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

As revealed by the above analysis, mobile payments have a significant impact on rural household consumption. It is worth noting that this effect has both similarities and differences for different groups. Next, this study focuses on the heterogeneous effects of mobile payments on the consumption of households with different incomes, education levels, and ages.

First, income is one of the most important factors affecting the consumption of a household. This paper divides the samples into two groups according to their income and examines if there is a heterogeneous effect of mobile payments on household income. The OLS and 2SLS estimation results of Columns (1) and (2) in Table 9 suggest that the effect of mobile payments on rural household consumption shows no significant difference across households with different income levels.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analysis.

Second, the use of mobile payments may also be related to the education level of the family. The higher the education level of the rural households, the higher probability of using mobile payments, and therefore the greater impact on consumer spending. According to the education level of the household head, this study divided rural households into two groups: below high school and high school and above. Different from this study’s expectation, estimation results in Columns (3) and (4) suggest that mobile payments have a stronger promotion effect on the consumption of rural households with lower education levels. One reason may be that the liquidity constraints channel and consumption choice channel brought by mobile payments are greater for lesser-educated households.

Finally, according to the life cycle theory, consumption patterns and structures of households of different ages also differ to a certain extent. This study divided households into young, middle-aged, and elderly (according to age 60) age groups and then investigated the heterogeneous effect of mobile payments on the consumption expenditure of rural households by age. The results in Columns (5) and (6) show that mobile payments play a greater role in promoting the consumption of young and middle-aged households. This finding is consistent with the expectation that young people usually have a higher probability of using new technology compared with older people.

Heterogeneity analysis shows that mobile payments have a strong boosting effect on the consumption of rural households with high-income and low-education levels and younger age structures. Therefore, the government needs to broaden the scope of mobile payment applications and further improve the convenience of its usage to allow low-income, low-educated, and elderly groups to enjoy the benefits of mobile payments.

5. The Effects on Consumption Structure and Pattern

5.1. Consumption Structure

As mentioned above, the popularity of mobile payments greatly improves the payment convenience of rural households, which may lead to a change in the rural households’ consumption concept. In this part, this study examined if the use of mobile payments could change the consumption structure of rural households in China. This study divided consumption into three types: subsistence, development, and enjoyment, and then investigated the different impacts of mobile payments on these three types of consumption. Table 10 presents the results of this investigation, which found that mobile payments significantly increase all three types of consumption in rural households. More specifically, this study discovered that the promotion effect of mobile payments on enjoyment consumption is significantly higher than the other two types of consumption, which implies that the application of mobile payments is helpful for consumption upgrading of rural households (that is, more income is invested in enjoyment goods, such as entertainment and education).

Table 10.

Mobile payment and consumption structure.

5.2. Offline Consumption

As an online payment method, will mobile payments crowd out the offline consumption of households? Previous studies have not reached a consistent conclusion for the above question. For example, Qin et al. (2017) [43] found that online shopping has a certain crowding-out effect on offline consumption due to the lower price of online shopping, while Liu and Zhang (2019) [44] showed that mobile payments could promote not only online consumption but also the increase the amount and frequency of offline consumption. At last, this study examined whether mobile payments affect the consumption pattern of rural households in China.

This paper used the total household consumption minus the total online shopping, which was regarded as the offline consumption of a rural household. The regression results are shown in Table 11, which discovers that mobile payments still play a major role in promoting rural households’ offline consumption. On the other side, according to the results in Columns (3) and (4) in Table 4, the use of mobile payments may reduce the proportion of rural households’ offline consumption in the total consumption expenditure. Overall, the results indicate that the use of mobile payments promotes the transformation of rural households’ consumption to online shopping but does not crowd out rural households’ offline consumption.

Table 11.

Mobile payment and offline consumption.

6. Conclusions

The consumption demand in rural areas is a potential market resource. How to build a new development pattern by releasing the consumer demand of rural households has become an important issue, especially facing the global economic decline since the COVID-19 shock.

Using representative survey data in China, this study investigated the effects of mobile payments on rural household consumption. This study’s empirical results indicate that the application of mobile payments significantly increases a rural household’s consumption by 29.8–52.3%, which can be attributed to three effects of mobile payment: easing liquidity constraints, enriching consumption choice, and improving the convenience of payment methods. Heterogeneous analysis shows that the impact of mobile payments on household consumption of the elderly and less educated is relatively higher. Moreover, this study finds that mobile payments significantly improve the enjoyment consumption of rural households, which is conducive to promoting the consumption upgrading of rural households. In addition, though it is encouraging rural households to consume more online, mobile payments did not crowd out rural households’ offline consumption.

Several implications emerge from this study. First, COVID-19 has had a negative impact on the world economy. Household consumption has declined due to the decline in income and the increase in income uncertainty. How to effectively boost household consumption is the key to sustainable economic development. The research of this paper finds that increasing the use of mobile payments can promote rural household consumption; Therefore, governments and relevant departments can actively encourage residents to use mobile payments by issuing e-coupons and other means, which will not only help control the spread of the epidemic but also effectively boost household consumption and promote consumption upgrading. Second, heterogeneity analysis shows that mobile payments have different impacts on the consumption of rural households with different income and education levels and age structures. To boost consumption in rural areas, the government needs to guarantee the income growth of rural residents further, strengthen the construction of educational infrastructure in rural areas, and properly handle the problem of rural aging so that different groups can enjoy the convenience brought by mobile payments. Third, mobile payments not only bring convenience to consumers, but also may bring risks, such as account theft and privacy disclosure. When the respondents were asked, “If they seldom or never use mobile payment tools, what is the main reason?”, 7.72% of respondents said they did not trust mobile payments and were afraid of exposing their privacy; Therefore, mobile payment enterprises and governments should not only strengthen the popularization of mobile payment methods but also attach great importance to the security and privacy protection of mobile payments. The risk management of mobile payments and the definition of the ownership of consumer data will become new problems in the development of the digital economy.

The research of this paper may have the following aspects to be expanded or improved upon; first of all, this paper mainly investigated the promotion effect of mobile payments on rural household consumption. However, the impact of mobile payments on household consumption is related to family preference, and the heterogeneity of family preferences is not deeply analyzed in this paper. Moreover, limited by the availability of data on key variables, this paper only used the data from the China Household Finance survey in 2017 in the empirical study. With the update of subsequent data, panel data can be used to draw more accurate conclusions further. Finally, the impact of mobile payments on the consumption gap and quality between urban and rural areas may be an important direction in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and P.Y.; Methodology, W.S.; Data curation, P.Y. and H.S.; Writing–original draft, W.Y., P.Y. and W.S.; Writing–review & editing, H.S. and W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 71903210; 72274228).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this manuscript are provided by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Horioka, C.Y.; Terada-Hagiwara, A. The Determinants and Long-term Projections of Saving Rates in Developing Asia. Jpn. World Econ. 2012, 24, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, C.Y. The Causes of Japan’s ‘Lost Decade’: The Role of Household Consumption. Jpn. World Econ. 2006, 18, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emran, M.S.; Hou, Z. Access to Markets and Rural Poverty: Evidence from Household Consumption in China. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 95, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, T.N.; Long, H.T.; Chi, L.V.; Tam, L.T.; Lebailly, P. Access to rural credit markets in developing countries, the case of Vietnam: A literature review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Sautmann, A. Credit constraints and the measurement of time preferences. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2021, 103, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, E. Mobile Money and Risk Sharing against Village Shocks. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 135, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.; Maier, E.; Wilken, R. The Effect of Credit Card versus Mobile Payment on Convenience and Consumers’ Willingness to Pay. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Risk Sharing and Transactions Costs: Evidence from Kenya’s Mobile Money Revolution. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 183–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrebi, S.; Jallai, J. Explain the Intention to Use Smartphones for Mobile Shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.J. The impact of digital finance on household consumption: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Gong, X. Mobile payment and rural household consumption: Evidence from China. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyi, E.D. The Effect of Mobile Technology on Self-Employment in Kenya. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadha, M.; Colbourn, T.; Seal, A. Mobile Money Use and Social Health Insurance Enrolment among Rural Dwellers Outside the Formal Employment Sector: Evidence from Kenya. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, D.M.; Katz, L.F. Rising Inequality? Changes in the Distribution of Income and Consumption in the 1980s. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 82, 546–551. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, J.; Yoo, K. Precautionary Behavior, Migrant Networks, and Household Consumption Decisions: An Empirical Analysis Using Household Panel Data from Rural China. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Santen, P. Uncertain Pension Income and Household Saving. Rev. Income Wealth 2019, 65, 908–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerbashian, V.; Kochanova, A. Tele-Communications 2.0, The Age of the Internet. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2018, 18, 20180068. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R. Information and Communication Technology Adoption and the Demand for Female Labor: The Case of Indian Industry. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 21, 695–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Herrera, E.; Martens, B.; Turlea, G. The Drivers and Impediments for Cross-Border E-commerce in the EU. Inf. Econ. Policy 2014, 28, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, F. ICT and Productivity Resurgence: A Growth Model for the Information Age. BE J. Macroecon 2007, 7, 20071470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Nordin, M. The Internet, News Consumption, and Political Attitudes—Evidence for Sweden. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2013, 13, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J.; Tarazi, M. Serving Smallholder Farmers: Recent Developments in Digital Finance; CGAP Focus Note No. 94; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ghose, A.; Xiao, B. Mobile Payment Adoption: An Empirical Investigation on Alipay; Working Paper 3270523; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.D.; Zhang, S. Mobile Payment Method and Heterogeneous Offline Consumer Behavior. China Bus. Mark. 2019, 33, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Pan, B.; Yin, Z. Pandemic, Mobile Payment, and Household Consumption: Micro-Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2378–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F.; Brumberg, R. Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data. Fr. Modigliani 1954, 1, 388–436. [Google Scholar]

- Chamon, M.D.; Prasad, E.S. Why are Saving Rates of Urban Households in China Rising? Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2010, 2, 93–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Zhu, G. Household Finance in China; Working Paper 23741; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.Z.; Deng, X.; Wang, G.H. Housing Rents and Household Consumption: Effect, Mechanism and Inequality. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.C.; Gong, X.; Guo, P.Y. The Impact of Mobile Payment on Entrepreneurship—Micro Evidence from China Household Finance Survey. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 3, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, G.J. The Economics of Information. J. Political Econ. 1961, 69, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Smith, M.D. Frictionless Commerce? A comparison of Internet and Conventional Retailers. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Jullien, B. Why do Intermediaries Divert Search? RAND J. Econ. 2011, 42, 337–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.J. The Effects of Utilitarian and Hedonic Online Shopping Value on Consumer Preference and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Umyarov, A.; Bapna, R.; Ramaprasad, J. Mobile as a Channel: Evidence from Online Dating. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Information Systems: Building a Better World through Information Systems, ICIS 2014, Auckland, New Zealand, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko, A.A. Financial Liberalization and Consumption Volatility in Developing Countries. IMF Staff Pap. 2005, 52, 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Deaton, A. Understanding Consumption; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.M.; Eisenkraft, N.; Bettman, J.; Chartrand, T.L. ‘Paper or Plastic?’: How We Pay Influences Post-Transaction Connection. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 42, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1980, 1, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.; Violante, G.; Weidner, J. The Wealthy Hand-to-Mouth; Working Paper 20073; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zeldes, S.P. Consumption and Liquidity Constraints: An Empirical Investigation. J. Political Econ. 1989, 97, 305–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Fan, G.; Hu, L.P. Market Index of China’s Province; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, F.; Wu, Y.; Wei, Z. Does Online Shopping Promote Household Consumption—Empirical Evidence from China’s Household Financial Survey (CHFS). Mod. Econ. Sci. 2017, 39, 104–114+126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, L. The Effects of Mobile Payment on Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).