The Effect of Identity Salience on Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Identity Salience and Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding

2.2. Relationship-Inducing and Non-Relationship-Inducing Factors

2.2.1. Relationship-Inducing Factors and Identity Salience

Community Cohesion

Psychological Empowerment

Satisfaction with the Government

2.2.2. Non-Relationship-Inducing Factors and Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding

Perceived Economic Benefits

Perceived Risk

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Social Connectedness

3. Research Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.3. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

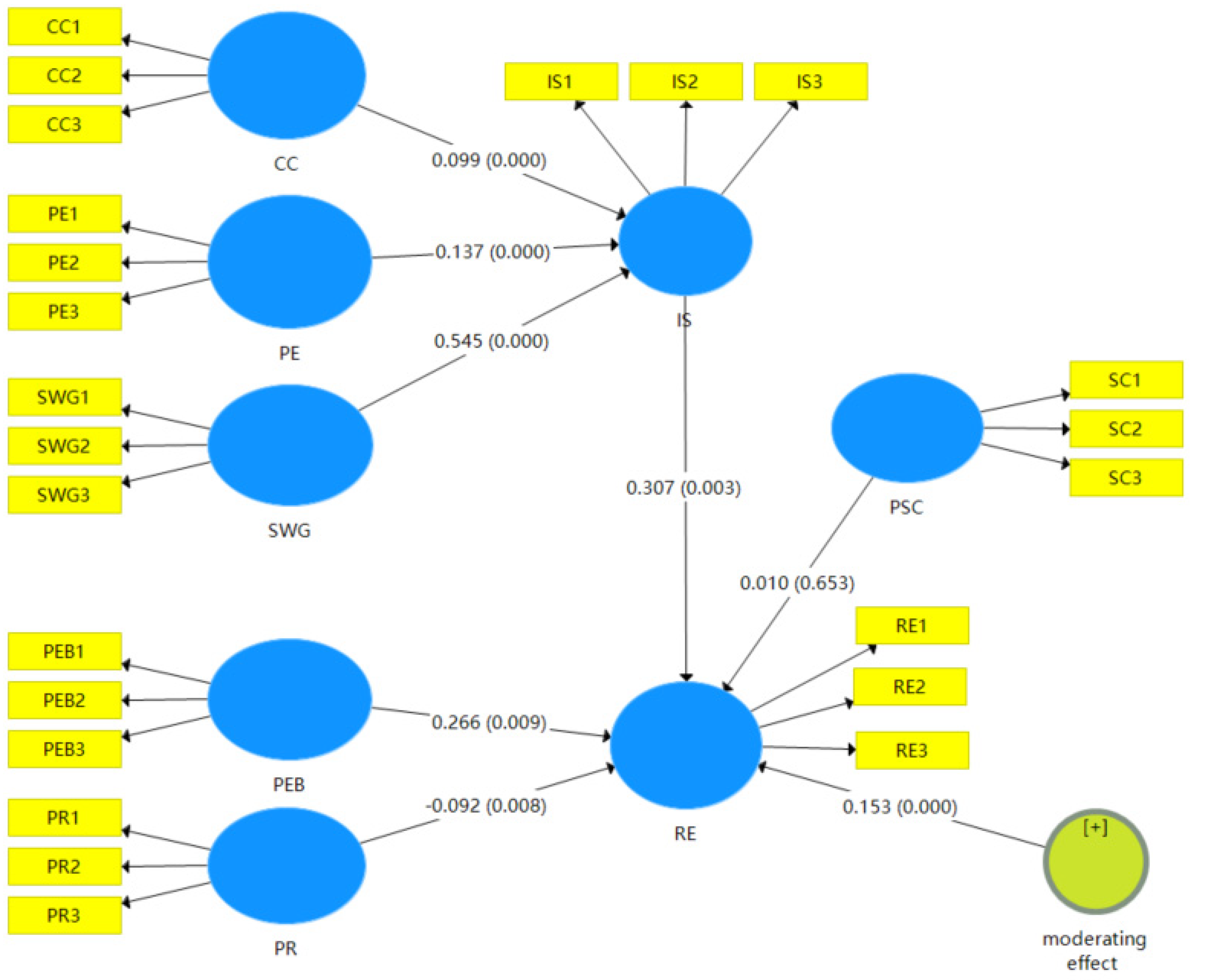

4.2. Structural Equation Model Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Identity Salience | Totally Agree | Totally Disagree | |||||

| 1. Sanya is a significant part of me. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2. For me, Sanya means more than where I am living. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3. The image of Sanya is something I usually think about. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Residents’ engagement in place branding (RE) | |||||||

| I contribute to improving residents’ experience in Sanya. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I make efforts to strengthen the image of Sanya as a tourism destination. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I “talk up” Sanya to people I know. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Community cohesion (CC) | |||||||

| I am closely related to my community. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I have developed fulfilling relationships with other members of the community. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I am always willing to help others in the community. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Psychological empowerment (PE) | |||||||

| Tourism in Sanya makes me proud to be a Sanya resident. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Tourism in Sanya makes me feel special because my city is famous. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Tourism in Sanya makes me want to talk more about my city. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Satisfaction with government (SWG) | |||||||

| The government made the right tourism decisions when the pandemic broke out. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| The government did what was right in tourism when the pandemic broke out. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| The government looked after the community’s interests during the pandemic. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Perceived economic benefit (PEB) | |||||||

| My family income is tied to tourism. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| My income has decreased sharply because of the Sanya tourism industry’s suffering. | |||||||

| My economic future depends on tourism. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Perceived risks (PR) | |||||||

| Tourists make me feel anxious during the pandemic period. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Tourists increase the risk of COVID-19 infection. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Tourists increase inconveniences in my daily activities. | |||||||

| Perceived social connectedness (SC) | |||||||

| I feel closely connected with my community during the pandemic. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I feel positive toward people connected with me during the pandemic. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Connection with others increases my belongingness during the pandemic. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Appendix B

References

- Ryu, K.; Promsivapallop, P.; Kannaovakun, P.; Kim, M.; Insuwanno, P. Residents’ risk perceptions, willingness to accept international tourists, and self-protective behaviour during destination re-opening amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 2022, 2054782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Tse, S.; Chan, D.C.F. Host-guest relations and destination image: Compensatory effects, impression management, and implications for tourism recovery. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The elusive destination brand and the ATLAS wheel of place brand management. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Alarcón, E.; Caballero-Galeote, L. Residents as Destination Influencers during COVID-19 Tourism Destination Management in a Post-Pandemic Context; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, F.G.; Templeton, A.; Smith, J.R.; Louis, W.R. Social norms, social identities and the COVID-19 pandemic: Theory and recommendations. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2021, 15, e125962021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe-Miyamoto, K.; Folk, D.; Lyubomirsky, S.; Dunn, E.W. Changes in social connection during COVID-19 social distancing: It’s not (household) size that matters, it’s who you’re with. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, L.M.; Ramar, P.; Roellinger, D.L.; Barry, B.A.; Sharma, P.; Ebbert, J.O. Changes in social relationships during an initial “stay-at-home” phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal survey study in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 274, 113779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.A.; Reicher, S.D.; Platow, M.J. The New Psychology of Leadership: Identity, Influence and Power; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowska, A.; Kaczmarek, Ł.D.; Kościelniak, M.; Urbańska, B. Values and well-being change amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J. Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19; Sage: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys, T.; Greenaway, K.H.; Ferris, L.J.; Rathbone, J.A.; Saeri, A.K.; Williams, E.; Parker, S.L.; Chang, M.X.; Croft, N.; Bingley, W. When trust goes wrong: A social identity model of risk taking. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J.; Hyun, S.S.; Kim, I. City residents’ perception of MICE city brand orientation and their brand citizenship behavior: A case study of Busan, South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, C.; Styvén, M.E.; Hultman, M. Places in good graces: The role of emotional connections to a place on word-of-mouth. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Wang, L.; Hung, K. Identity and destination branding among residents: How does brand self-congruity influence brand attitude and ambassadorial behavior? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchinaka, S.; Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.-S. Classifying residents’ roles as online place-ambassadors. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Wang, L.; Hung, K. Residents’ power and trust: A road to brand ambassadorship? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.C.; McWhirter, B.T. Connectedness: A review of the literature with implications for counseling, assessment, and research. J. Couns. Dev. 2005, 83, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorato, R.S.; Turner, J.C. Fluidity in the self-concept: The shift from personal to social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.-L. Editor’s essay: Identity and/in/of public relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 2018, 30, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Issues, identity salience, and individual sense of connection to organizations: An identity-based approach. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelter, J.W. The effects of role evaluation and commitment on identity salience. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1983, 46, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Pae, T., II; Bendle, L.J. The role of identity salience in the leisure behavior of film festival participants: The case of the Busan international film festival. J. Leis. Res. 2016, 48, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Volunteer identity salience, role enactment, and well-being: Comparisons of three salience constructs. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2013, 76, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Self-uncertainty, leadership preference, and communication of social identity. Atl. J. Commun. 2018, 26, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.; Seate, A.A. Group membership in race-related media processes and effects. In The Handbook of Intergroup Communication; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.A.; Keerie, N.; Palomares, N.A. Language, gender salience, and social influence. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 22, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, B.M.; Mania, E.W.; Gaertner, S.L. Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, D.B.; German, S.D.; Hunt, S.D. The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.I.; Moldoveanu, M. When will stakeholder groups act? An interest-and identity-based model of stakeholder group mobilization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, S.; Helmig, B. What do we know about the identity salience model of relationship marketing success? A review of the literature. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2008, 7, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jia, B.; Huang, Y. How do destination negative events trigger tourists’ perceived betrayal and boycott? The moderating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Lian, Q.; Huang, Y. How do tourists’ attribution of destination social responsibility motives impact trust and intention to visit? The moderating role of destination reputation. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.M.; Siguaw, J.A. Destination word of mouth: The role of traveler type, residents, and identity salience. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S. Reconstructing the place branding model from the perspective of Peircean semiotics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Pradhan, S.; Bashir, M.; Roy, S.K. Customer-based place brand equity and tourism: A regional identity perspective. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.W.; Luna, D. Effects of national identity salience on responses to ads. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbjørnsen, H.; Pedersen, P.E.; Nysveen, H. “This is who I am”: Identity expressiveness and the theory of planned behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, A.N.; Adam, I.; Dayour, F.; de Jong, A. COVID-19-induced redundancy and socio-psychological well-being of tourism employees: Implications for organizational recovery in a resource-scarce context. J. Travel Res. 2021, 62, 00472875211054571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsut, C.; Kuran, C.; Kruke, B.I.; Nævestad, T.O.; Orru, K.; Hansson, S. A critical appraisal of individual social capital in crisis response. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2022, 13, 176–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Boley, B.B.; Yang, F.X. Resident Empowerment and Support for Gaming Tourism: Comparisons of Resident Attitudes Pre-and Amid-COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 2022, 10963480221076474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Russell, Z.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Denley, T.J.; Rojas, C.; Hadjidakis, E.; Barr, J.; Mower, J. Residents’ pro-tourism behaviour in a time of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1858–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutlu, M.E.; Bakır, A.C.; Sönmez, H.; Zorer, E.; Alvarez, M.D. Factors affecting intended hospitable behavior to tourists: Hosting Chinese tourists in a post-COVID-19 world. Anatolia 2021, 32, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Xu, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibaba, H.; Karlsson, L.; Dolnicar, S. Residents open their homes to tourists when disaster strikes. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. Building resilience. In Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012; 166p. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, L.; Im, J.; So, K.K.F.; Cao, Y. Post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 95, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantle, T. Community Cohesion: A New Framework for Race and Diversity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, J.E. A three-factor model of social identity. Self Identity 2004, 3, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. Community cohesion after a natural disaster: Insights from a Carlisle flood. Disasters 2010, 34, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetherell, M. Community cohesion and identity dynamics: Dilemmas and challenges. In Identity, Ethnic Diversity and Community Cohesion; Wetherell, M., Lafleche, M., Berkeley, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. Giving peace a chance: Organizational leadership, empowerment, and peace. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelble, T.A. Ecology, economy and empowerment: Eco-tourism and the game lodge industry in South Africa. Bus. Politics 2011, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, S.D. Social identity and social change: Rethinking the context of social psychology. In Social Groups and Identities: Developing the Legacy of Henri Tajfel; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J.; Reicher, S. Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: Researching crowds and power. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.S. Effect of psychological empowerment on commitment of employees: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences (CHHSS 2011), Cairo, Egypt, 21–23 October 2011; Volume 17, pp. 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, M.S.; Ganster, D.C. The effects of empowerment on attitudes and performance: The role of social support and empowerment beliefs. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1523–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welbourne, T.M.; Cable, D.M. Group incentives and pay satisfaction: Understanding the relationship through an identity theory perspective. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, G.; Simmons, J. Identities and Interactions, revised ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Dwyer, L. Residents’ place satisfaction and place attachment on destination brand-building behaviors: Conceptual and empirical differentiation. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Dwyer, L.; Firth, T. Residents’ place attachment and word-of-mouth behaviours: A tale of two cities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Gursoy, D.; Wall, G. Residents’ support for red tourism in China: The moderating effect of central government. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E. The end of over-tourism? Opportunities in a post-COVID-19 world. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Chang, M.; Kim, M. Exploring the Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Measures and Awareness of the Tourism Crisis for Residents’ Tourism Attitude. J. Ind. Distrib. Bus. 2021, 12, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Lai, I.K.W. Effect of government enforcement actions on resident support for tourism recovery during the COVID-19 crisis in Macao, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Sangpikul, A. Resident perceptions towards COVID-19 public policies for tourism reactivation: The case of Thailand. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2022, 2022, 2076689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H. Does living in the vicinity of heritage tourism sites influence residents’ perceptions and attitudes? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1295–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Rodrigues, A.; Fernandes, D.; Pires, C. The role of local government management of tourism in fostering residents’ support to sustainable tourism development: Evidence from a Portuguese historic town. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2016, 6, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M.; Watson, A. Place distinctiveness, psychological empowerment, and support for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, E.P.; Boley, B.B.; Woosnam, K.M.; Green, G.T. Modeling residents’ attitudes toward short-term vacation rentals. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, X.; Guo, Y. Residents’ Engagement Behavior in Destination Branding. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R.; Staelin, R. A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilaki, M.J.M.; Abooali, G.; Marzbali, M.H.; Samat, N. Vendors’ attitudes and perceptions towards international tourists in the Malaysia night market: Does the COVID-19 outbreak matter? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppala, E.; Rossomando, T.; Doty, J.R. Social connection and compassion: Important predictors of health and well-being. Soc. Res. Int. Q. 2013, 80, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Keh, H.T.; Chao, C.H. Nostalgia and consumer preference for indulgent foods: The role of social connectedness. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntontis, E.; Drury, J.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Williams, R. What lies beyond social capital? The role of social psychology in building community resilience to climate change. Traumatology 2020, 26, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitas, N.; Ehmer, C. Social Capital in the Response to COVID-19. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stürmer, S.; Snyder, M.; Kropp, A.; Siem, B. Empathy-motivated helping: The moderating role of group membership. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetterberg, L.; Santosa, A.; Ng, N.; Karlsson, M.; Eriksson, M. Impact of COVID-19 on neighborhood social support and social interactions in Umeå Municipality, Sweden. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 685737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M.A.; Chen, C.-A. Public employees’ use of social media: Its impact on need satisfaction and intrinsic work motivation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jun, M.; Han, J. The relationship between needs, motivations and information sharing behaviors on social media: Focus on the self-connection and social connection. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieling, J.; Ong, C.-E. Warfare tourism experiences and national identity: The case of Airborne Museum ‘Hartenstein’in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, L.; Stephen, A.T.; Coleman, N.V. When posting about products on social media backfires: The negative effects of consumer identity signaling on product interest. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGIB. 2021 Sanya City National Economic and Social Development Statistical Bulletin. 2022. Available online: http://tjj.sanya.gov.cn/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Somer, E.; Maguen, S.; Moin, V.; Boehm, A.; Metzler, T.J.; Litz, B.T. The effects of perceived community cohesion on stress symptoms following a terrorist attack. J. Psychol. Trauma 2008, 7, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Lai, I.K.W. The mechanism influencing the residents’ support of the government policy for accelerating tourism recovery under COVID-19. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, T.D. Who Should the Military Recruit? The Effects of Institutional, Occupational, and Self-Enhancement Enlistment Motives on Soldier Identification and Behavior. Armed. Soc. 2017, 43, 579–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M.-L. A resource-based typology of dynamic capability: Managing tourism in a turbulent environment. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.R.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, L. Exploring posttraumatic growth after the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Manag. 2022, 90, 104474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarczyk, A.; Basabe, N.; Páez, D.; Villagrán, L.; Reyes, C. Individual and collective posttraumatic growth in victims of natural disasters: A multidimensional perspective. J. Loss Trauma 2017, 22, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H. Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Berger, J.; Menon, G. When identity marketing backfires: Consumer agency in identity expression. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Nawijn, J.; von Zumbusch, J. A new materialist governance paradigm for tourism destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerlad, A.; Marston, L.; Huntley, J.; Livingston, G.; Lewis, G.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Social relationships and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal analysis of the COVID-19 Social Study. In Psychological Medicine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Capielo Rosario, C.; Abreu, R.L.; Gonzalez, K.A.; Cardenas Bautista, E. “That day no one spoke”: Florida Puerto Ricans’ reaction to hurricane María. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 48, 377–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 283 | 44.9 |

| Male | 347 | 55.1 |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 | 211 | 33.5 |

| 31–40 | 174 | 27.6 |

| 41–50 | 82 | 13.0 |

| 51+ | 163 | 25.9 |

| Household income (per month) | ||

| Less than USD 719 | 127 | 20.1 |

| USD 719-USD 2158 | 342 | 54.3 |

| More than USD 2158 | 161 | 25.6 |

| Education | ||

| Middle school or lower | 57 | 9.1 |

| High school/vocational school | 162 | 25.7 |

| College/university | 317 | 50.3 |

| Master’s or Ph. D. | 94 | 14.9 |

| Scale and Item Description | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | Compositive Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity salience (IS) | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.95 | |

| Sanya is a significant part of me. | 0.93 | |||

| For me, Sanya means more than where I am living. | 0.93 | |||

| The image of Sanya is something I usually think about. | 0.94 | |||

| Residents’ engagement in place branding (RE) | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.95 | |

| I contribute to improving residents’ experience in Sanya. | 0.91 | |||

| I make efforts to strengthen the image of Sanya as a tourism destination. | 0.94 | |||

| I “talk up” Sanya to people I know. | 0.95 | |||

| Community cohesion (CC) | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.92 | |

| I am closely related to my community. | 0.92 | |||

| I have developed fulfilling relationships with other members of the community. | 0.86 | |||

| I am always willing to help others in the community. | 0.92 | |||

| Psychological empowerment (PE) | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.93 | |

| Tourism in Sanya makes me proud to be a Sanya resident. | 0.90 | |||

| Tourism in Sanya makes me feel special because my city is famous. | 0.86 | |||

| Tourism in Sanya makes me want to talk more about my city. | 0.93 | |||

| Satisfaction with government (SWG) | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.96 | |

| The government made the right tourism decisions when the pandemic broke out. | 0.94 | |||

| The government did what was right in tourism when the pandemic broke out. | 0.94 | |||

| The government looked after the community’s interests during the pandemic. | 0.96 | |||

| Perceived economic benefit (PEB) | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.95 | |

| My family income is tied to tourism. | 0.95 | |||

| My income has decreased sharply because of the Sanya tourism industry’s suffering. | 0.94 | |||

| My economic future depends on tourism. | 0.96 | |||

| Perceived risks (PR) | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.81 | |

| Tourists make me feel anxious during the pandemic period. | 0.80 | |||

| Tourists increase the risk of COVID-19 infection. | 0.81 | |||

| Tourists increase inconveniences in my daily activities. | 0.68 | |||

| Perceived social connectedness (SC) | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.93 | |

| I feel closely connected with my community during the pandemic. | 0.91 | |||

| I feel positive toward people connected with me during the pandemic. | 0.94 | |||

| Connection with others increases my belongingness during the pandemic. | 0.95 |

| CC | IS | PE | PEB | PR | RE | SC | SWG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 0.89 | |||||||

| IS | 0.21 | 0.94 | ||||||

| PE | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.90 | |||||

| PEB | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.93 | ||||

| PR | −0.36 | −0.16 | −0.29 | −0.14 | 0.77 | |||

| RE | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 0.56 | −0.07 | 0.93 | ||

| SC | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.18 | −0.35 | 0.10 | 0.90 | |

| SWG | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.57 | −0.09 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 0.95 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | T Values | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Identity salience-> Resident engagement | 0.31 | 2.99 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| H2a: Community cohesion-> Identity salience | 0.10 | 4.11 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| H2b: Psychological empowerment-> Identity salience | 0.14 | 5.54 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| H2c: Satisfaction with government-> Identity salience | 0.55 | 16.00 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| H3a: Perceived economic benefits-> Resident engagement | 0.27 | 2.58 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| H3b: Perceived risk-> Resident engagement | −0.10 | 2.60 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

| Moderating effect | ||||

| H4: Perceived social connectedness × identity salience -> Resident engagement | 0.15 | 5.01 | <0.01 *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, W.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J. The Effect of Identity Salience on Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010357

Han W, Tang Y, Wang J. The Effect of Identity Salience on Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010357

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Wei, Yuwei Tang, and Jiayu Wang. 2023. "The Effect of Identity Salience on Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010357

APA StyleHan, W., Tang, Y., & Wang, J. (2023). The Effect of Identity Salience on Residents’ Engagement with Place Branding during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(1), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010357