Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development—A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impacts of Tourism Development

2.2. Residents’ Support towards Tourism Development

3. Materials and Methods

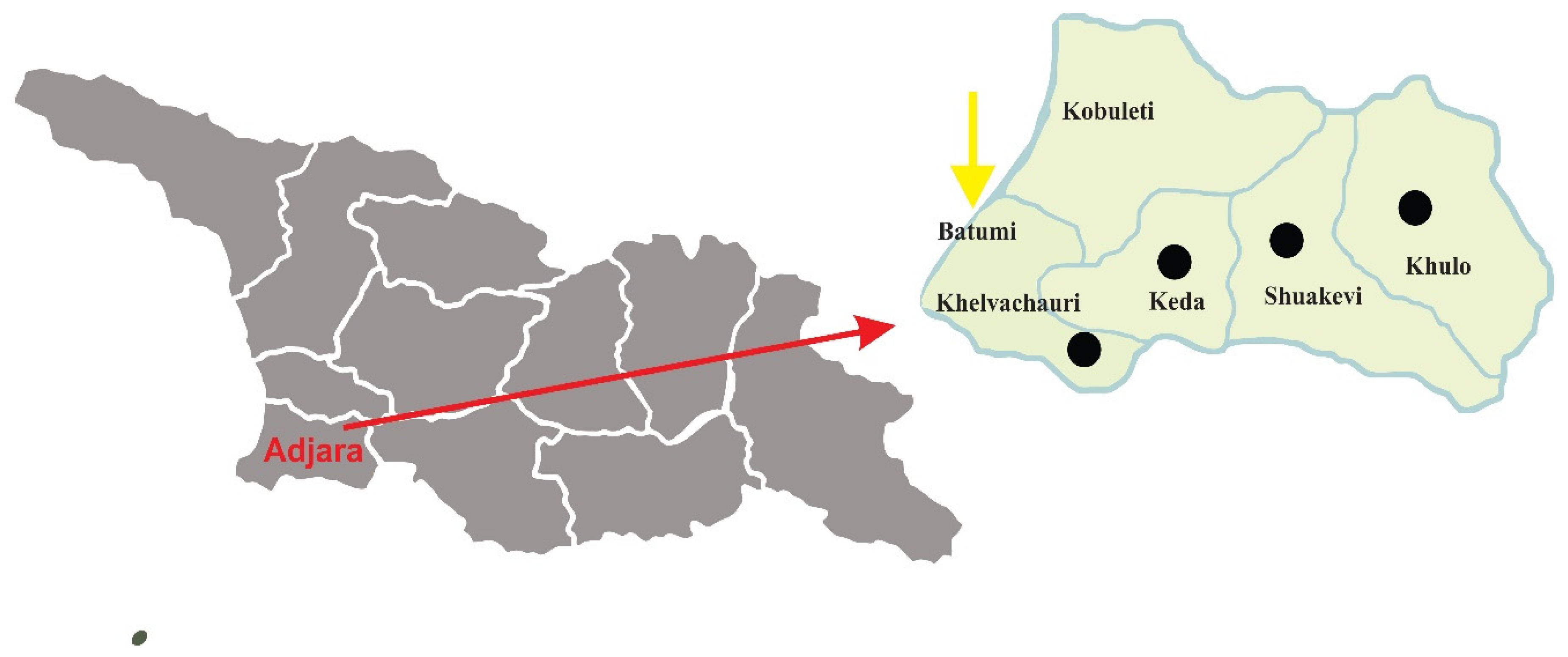

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Survey Design

3.3. Sample Size

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Perception towards Tourism Development Impact

4.2. Support for Tourism Development

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brankov, J.; Penjišević, I.; Ćurčić, N.B.; Živanović, B. Tourism as a Factor of Regional Development: Community Perceptions and Potential Bank Support in the Kopaonik National Park (Serbia). Sustainability 2019, 11, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Fatah, A.O.; Dumitras, D.E. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions of the Socio-Cultural Benefits of Tourism Development in the Mountain Area. Societies 2021, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lorenzo, A.; Lyu, J.; Babar, Z.U. Tourism and Development in Developing Economies: A Policy Implication Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, F.C.; García Martínez, C. Landscape and Tourism as Tools for Local Development in Mid-Mountain Rural Areas in the Southeast of Spain (Castilla-La Mancha). Land 2021, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderová, I.; Scholz, P.; Almeida, N. Attitudes of local population towards the impacts of tourism development: Evidence from Czechia. Front. Psychol. 2021, 2028, 684773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.; Russo, L.; Parisi, F.; Notarianni, M.; Manuelli, S.; Carvao, S. Mountain Tourism—Towards a More Sustainable Path; FAO: Rome, Italy; The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wassie, S.B. Natural resource degradation tendencies in Ethiopia: A Review. Environ. Syst. Res. 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frînculeasa, M.N.; Chiţescu, R.I. The perception and attitude of the resident and tourists regarding the local public administration and the tourism phenomenon. HOLISTICA–J. Bus. Public Adm. 2018, 9, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salukvadze, G.; Backhaus, N. Is Tourism the Beginning or the End? Livelihoods of Georgian Mountain People at Stake. Mt. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, R28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiranashvili, A.; Chargazia, K.; Matzarakis, A.; Kartvelishvili, L. Tourism climate index in the coastal and mountain locality of Adjara, Georgia. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Sustainable Mountain Regions: Make Them Work”, Borovets, Bulgaria, 14–16 May 2015; pp. 238–244, ISBN 978-954-411-220-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetskhladze, T.; Khakhubia, N. Popularization of mountainous regions in pandemic conditions and positioning them as a tourist destination. ЛTEY 2021, 193. Available online: https://er.chdtu.edu.ua/bitstream/ChSTU/3216/1/conrefence-tourism2021.pdf#page=196 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Putkaradze, M.; Gorgiladze, N. Tourism and Ecology in Adjara, Georgia: A Preliminary Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 5, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gogitidze, G.; Nadareishvili, N. Access to information about the tourist products of mountainous Adjara for tourists and visitor to the Adjara region. In Proceedings of the SADAB 8th International Online Conference on Social Researches and Behavioral Sciences, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 22–24 April 2021; pp. 174–183, ISBN 978-625-00-9970-4. [Google Scholar]

- Beridze, N. Agro-Tourism Perspectives of Adjara Region and International Tourist Market Requirements. In Proceedings of the 7th Eurasian Multidisciplinary Forum, EMF, Tbilisi, Georgia, 6–7 October 2017; p. 421. Available online: https://gruni.edu.ge/uploads/files/News/2017/10/7th_EMF_2017.pdf#page=432 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Bakhtadze, E.; Phalavandishvili, N. Identifying tourism market growth opportunities and risks in the autonomous republic in ajara (georgia). In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference “ECONOMIC SCIENCE FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT” No 54, Jelgava, Latvia, 12–15 May 2020; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO, Toolkit on Poverty Reduction through Tourism in Rural Areas. 2011. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/instructionalmaterial/wcms_176290.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Schubert, S.F. Coping with Externalities in Tourism: A Dynamic Optimal Taxation Approach. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Xiaoli, P.; Bihu, W. Research on residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts and attitudes: A case study of Pingyao ancient city. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism (IFoU), Tourbanism, Barcelona, 25–27 January 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Oroian, C.F.; Dumitras, D.E.; Mihai, V.C.; Ilea, M.; Chiciudean, D.I.; Gliga, I.D.; Chiciudean, G.O. Residents’ Perception of Destination Quality: Key Factors for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, H.; Rastogi, R. Social and psychological factors influencing destination preferences of domestic tourists in India. Leis. Stud. 2013, 32, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshliki, S.A.; Kaboudi, M. Perception of community in tourism impacts and their participation in tourism planning: Ramsar, Iran. J. Asian Behav. Stud. 2012, 2, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetic, S. Specific features of rural tourism destinations management. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2012, 1, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, C.M.; Rossi, S.; Barros, A. Assessing the impacts of mountain biking and hiking on subalpine grassland in Australia an experimental protocol. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 3049–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Naidoo, P. Residents’ attitudes toward perceived tourism benefits. Int. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2011, 4, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Domecq, C.; Pritchard, A.; Segovia-Perez, M.; Morgan, N.; Villace-Molinero, T. Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Zulkifly, M.I. Local Community Attitude and Support towards Tourism Development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackie, I. The impact of wildlife hunting prohibition on the rural livelihoods of local communities in Ngamiland and Chobe District Areas, Botswana. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1558716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-Y.; Yu, H.-W.; Hsieh, C.-M. Evaluating Forest Visitors’ Place Attachment, Recreational Activities, and Travel Intentions under Different Climate Scenarios. Forests 2021, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutoshi, S.B.; Ali, A.; Shedayi, A.A.; Khan, G. Residents’ Perception of Impact of Mass Tourism on Mountain Environment in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2022, 12, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, F.; Redzuan, M.; Gill, S.S. Community Perceptions towards Economic and Environmental Impacts of Tourism on Local Communities. Asian Soc. Sci. 2009, 5, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngowi, R.E.; Jani, D. Residents’ perception of tourism and their satisfaction: Evidence from Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Dev. S. Afr. 2018, 35, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Xue, Q. Tourism’s Impacts on Natural Resources: A Positive Case from China. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Abdelmoaty, M.A. Impact of Rural Tourism Development on Residents’ Satisfaction with the Local Environment, Socio-Economy and Quality of Life in Al-Ahsa Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez López, F. Unemployment and Growth in the Tourism Sector in Mexico: Revisiting the Growth-Rate Version of Okun’s Law. Economies 2019, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoudakis, K.I.; McCabe, S.; Story, V. Social tourism and self-efficacy: Exploring links between tourism participation, job-seeking and unemployment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Weng, L. Transformation of Rural Space under the Impact of Tourism: The Case of Xiamen, China. Land 2022, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sha, H.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Exploring the Relationship between Perceived Community Support and Psychological Well-Being of Tourist Destinations Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongbuamai, N.; Bui, Q.; Yousaf, H.M.A.U.; Liu, Y. The impact of tourism and natural resources on the ecological footprint: A case study of ASEAN countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 19251–19264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Bosley, H.E.; Dronberger, M.G. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Noble, G.; Johnson, L.W. Conceptualising a contemporary marketing mix for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. Editorial: Land Issues and Their Impact on Tourism Development. Land 2022, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateoc-Sîrb, N.; Albu, S.; Rujescu, C.; Ciolac, R.; Țigan, E.; Brînzan, O.; Mănescu, C.; Mateoc, T.; Milin, I.A. Sustainable Tourism Development in the Protected Areas of Maramureș, Romania: Destinations with High Authenticity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Kušcer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębski, P.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Oklevik, O. Tourism Investment Gaps in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.-C.; Janta, P. Resident’s Perspective on Developing Community-Based Tourism – A Qualitative Study of Muen Ngoen Kong Community, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Front. Psychol 2020, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Díaz-Armas, R.; Gutierrez-Taño, D. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts on Island Destinations: A Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Cañizares, S.M.; Castillo Canalejo, A.M.; Núñez Tabales, J.M. Stakeholders’ perceptions of tourism development in Cape Verde, Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kožić, I. Can tourism development induce deterioration of human capital? Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D.; Vieregge, M. Residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A factor-cluster approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, C.; Santos, M.C.; Águas, P.; Santos, J.A.C. Sustainability as a key driver to address challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsurang, P.; Kiatthanawat, A.; Sanoamuang, P.; Kraseain, A. and Pinijvarasin, W. Community-based tourism and heritage consumption in Thailand: An upside-down classification based on heritage consumption. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2096531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.; Cheyne, J. Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L. Analysing the Gender Dimensions of Tourism as a Development Strategy. Policy Papers del Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales 09-03, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales. 2009. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/10237/1/PP_03-09.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Liu, X.R.; Li, J.J. Host Perceptions of Tourism Impact and Stage of Destination Development in a Developing Country. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S. Including young mothers: Community-based participation and the continuum of active citizenship. Community Dev. J. 2005, 42, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Cottrell, S.P. A sustainable tourism framework for monitoring residents’ satisfaction with agritourism in Chongdugou Village, China. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2008, 1, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Timothy, D.J. Arguments for community participation in tourism development. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marzuki, A.; Hay, I.; James, J. Public participation shortcomings in tourism planning: The case of the Langkawi Islands, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakuni, K. Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism, Focusing on Ecocecentric Attitudes and Perceptions of Economic Costs: The Case of Iriomote Island, Japan. Ph.D Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paulauskienė, L. The tourism management principles and functions on local level. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2013, 35, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.H.; Kayat, K. Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact and their support for tourism development: The case study of Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 4, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G. Demographic analysis of residents’ support for tourism development in Jamaica. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.-F.; Lo, M.-C. Community involvement and sustainable rural tourism development: Perspectives from the local communities. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Tešin, A.; Božović, T.; Milošević, D. Residents’ perceptions of and satisfaction with tourism development: A case study of the Uvac Special Nature Reserve, Serbia. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, N.; Numata, S. Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 2510–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Ewnetu, B. Community participation in tourism development as a tool to foster sustainable land and resource use practices in a national park milieu. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Reid, D.G. Community Integration. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. Communitybased tourism development model and community participation. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination–Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Gursoy, D. An examination of changes in residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts over time: The impact of residents’ socio-demographic characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brougham, J.; Butler, R. A segmentation analysis of resident. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 1981, 6, 170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-García, F.; Peláez-Fernández, M.Á.; Balbuena-Vázquez, A.; Cortés-Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ryan, C. Perceptions of place, modernity and the impacts of tourism—Differences among rural and urban residents of Ankang, China: A likelihood ratio analysis. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R.; Potts, T. Tourism Planning in Historic Districts: Attitudes toward Tourism Development in Charleston. J. Am. Plan Assoc. 2003, 69, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Al Subhi, S.; Meesala, K.M. Community Perception and Attitude towards Sustainable Tourism and Environmental Protection Measures: An Exploratory Study in Muscat, Oman. Economies 2022, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M.; Szromek, A.R. Influence of the Residents’ Perception of Overtourism on the Selection of Innovative Anti-Overtourism Solutions. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, D.; Radovanović, M.; Petrović, M.D.; Cimbaljević, M.; Vuksanović, N.; Vuković, D.B. Environmental and Community Stability of a Mountain Destination: An Analysis of Residents’ Perception. Sustainability 2018, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Competitive Advantages of the Mountainous Regions of Georgia. July 2019. Available online: http://tvitmmartveloba.ge/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/High%20Mounteneous%20Regions_ENG.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Brida, J.G.; Disenga, M.; Osti, L. Residents’ perception and attitudes towards tourism impacts: A case study of the small rural community of Folgaria (Trentino—Italy). Int. J. 2011, 18, 359–385. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Uppersaddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gorusch, R.L. Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomljenovic, R.; Faulkner, B. Tourism and older residents in a sunbelt resort. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baros, Zoltan and Dávid, Lorant Denes: Environmentalism and Sustainable Development from the Point of view of Tourism. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2007, 2, 141–152.

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Accommodation | No. of Hotels | No. of Rooms | No. of Beds-Places |

|---|---|---|---|

| The number of hotels in resorts in the mountainous area of Adjara | 20 | 204 | 612 |

| The number of family hotels/cottages in Khelvachauri mountain area | 17 | 62 | 173 |

| The number of family hotels/cottages in Keda | 19 | 62 | 151 |

| The number of family hotels/cottages in Shuakhevi | 29 | 117 | 303 |

| The number of family hotels/cottages in Khulo | 15 | 58 | 151 |

| Total (hotels, family hotels, cottages) | 100 | 503 | 1390 |

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 349 (56.2%) |

| Male | 271 (43.8%) |

| Age | |

| 18–30 years | 354 (57.1%) |

| >30 years | 266 (42.9%) |

| Education level | |

| Secondary (8 classes) | 13 (2.1%) |

| Vocational | 63 (10.1%) |

| High school | 105 (16.9%) |

| University degree | 439 (70.8%) |

| Items | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| The development of tourism increases crime rate | 2.141 | 0.8444 |

| Tourism development will increase environment pollution (air, water, soil) | 2.200 | 0.8012 |

| The development of tourism determines litter quantity increase | 2.247 | 0.8006 |

| The development of tourism is associated with the loss of traditions | 2.029 | 0.7701 |

| Tourism is an opportunity for development | 4.251 | 0.6567 |

| The development of tourism increases life quality for the community | 4.227 | 0.5973 |

| Tourism development increases the production and sale of local products | 4.359 | 0.5989 |

| The development of tourism will contribute to the development of new tourist areas | 4.348 | 0.5540 |

| Tourism development will create new jobs | 4.390 | 0.5943 |

| Tourism development ensures the protection and conservation of natural resources | 3.980 | 0.7617 |

| Tourism development ensures the restoration and preservation of historic buildings | 4.209 | 0.7081 |

| The development of tourism will increase the level of awareness and education of the residents | 4.203 | 0.6499 |

| The development of tourism will facilitate the implementation of a variety of cultural events | 4.220 | 0.6016 |

| Tourism will help popularize Georgian culture | 4.379 | 0.5846 |

| Eigenvalue | Variance % | Factor | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.2 | 42.43 | Positive effects α = 0.926 mean = 4.23 | Tourism development will create new jobs | 0.811 |

| The development of tourism will contribute to the development of new tourist zones | 0.809 | |||

| The development of tourism will increase the level of awareness and education of the residents | 0.797 | |||

| The development of tourism will facilitate the implementation of a variety of cultural events | 0.792 | |||

| The development of tourism increases the quality of life of the community | 0.791 | |||

| Tourism will help popularize Georgian culture | 0.768 | |||

| Tourism development ensures the restoration/preservation of historic buildings | 0.755 | |||

| Tourism development increases the production and sale of local products | 0.753 | |||

| Tourism is an opportunity for development | 0.742 | |||

| Tourism development ensures the protection and conservation of natural resources | 0.639 | |||

| 2.3 | 18.90 | Negative effects α = 0.823 mean = 2.16 | Tourism development will increase environmental pollution (air, water, soil) | 0.872 |

| The development of tourism determines litter quantity increase | 0.845 | |||

| The development of tourism increases crime rate | 0.757 | |||

| The development of tourism is associated with the loss of traditions | 0.675 | |||

| Total variance % | 61.33 | |||

| Cronbach’s alpha | α = 0.788 |

| Dependent Variable | Means | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| Positive effects | 4.19 ± 0.428 | 4.28 ± 0.528 | 2.103 | 0.036 * |

| Negative effects | 2.24 ± 0.653 | 2.09 ± 0.683 | 2.43 | 0.015 * |

| Less than 30 years | More than 30 years | |||

| Positive effects | 4.18 ± 0.532 | 4.25 ± 0.457 | 1.16 | 0.108 |

| Negative effects | 2.26 ± 0.605 | 2.14 ± 0.693 | 1.84 | 0.066 |

| Education Level | Means For Positive Effects | Means for Negative Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary (8 classes) | 3.84 ± 0.766 | 2.10 ± 0.630 |

| Vocational | 4.12 ± 0.630 | 2.39 ± 0.903 |

| High school | 4.19 ± 0.447 | 2.19 ± 0.763 |

| University degree | 4.27 ± 0.432 | 2.13 ± 0.584 |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.113 ** | −0.059 |

| Variable | Dependent Variable: “I Intend to Have a Guest House” | Dependent Variable: “I Want to Share Information about the Traditions to Visitors” | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ration | p-Value | 95% CI | Odds Ration | p-Value | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Higher | Lower | Higher | |||||

| Positive effects | 0.850 | 0.145 | 0.684 | 1.057 | 2.474 | 0.043 * | 1.027 | 5.957 |

| Negative effects | 0.501 | 0.001 ** | 0.331 | 0.759 | 1.843 | 0.463 | 0.360 | 9.444 |

| Gender (Male = 1) | 1.049 | 0.864 | 1.001 | 2.955 | 0.606 | 0.655 | 0.068 | 5.432 |

| Age (>30 years = 1) | 1.720 | 0.042 * | 0.605 | 1.820 | 1.805 | 0.618 | 0.177 | 18.412 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gogitidze, G.; Nadareishvili, N.; Harun, R.; Arion, I.D.; Muresan, I.C. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development—A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010492

Gogitidze G, Nadareishvili N, Harun R, Arion ID, Muresan IC. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development—A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010492

Chicago/Turabian StyleGogitidze, Giorgi, Nana Nadareishvili, Rezhen Harun, Iulia D. Arion, and Iulia C. Muresan. 2023. "Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development—A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010492

APA StyleGogitidze, G., Nadareishvili, N., Harun, R., Arion, I. D., & Muresan, I. C. (2023). Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development—A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area. Sustainability, 15(1), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010492