Abstract

An individual’s sense of place has a motivational impetus on how s/he relates to the place. Thus, environmentally sustainable behaviors are deemed as products of a person’s sense of place. However, little is known about the extent to which geospatial thinking conditions a person’s sense of place. Accordingly, this study builds a theoretical model that examines the influence of geospatial thinking on a person’s sense of place. Further, it investigates the mediating role of creativity. A survey data from 1037 senior high school students in western China was utilized to test the theoretical model. The findings indicate that students’ geospatial thinking has a positive relationship with their creative behaviors and sense of place. Students’ creativity was found to facilitate their sense of place. Moreover, students’ creativity was discovered to mediate the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. These results provide useful implication for the cultivation of students’ sense of place. In this regard, geography education has the critical role in improving students’ geospatial thinking skills to stimulate creative behaviors for a better sense of place.

1. Introduction

Sense of place is a socially, culturally, and psychologically constructed relationship that stems from the interaction between people and places [1,2]. The concept encompasses an individual’s emotions, perceptions, and attitudes attributable to a place [3]. That is, sense of place is defined as people’s identification, attachment, and dependence on place. The importance of a sense of place is indisputable. A strong sense of place and environmental awareness jointly promote pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors [4]. Thus, a sense of place constrains people’s actions and provides a way to mitigate local economic and environmental conflicts [5]. Moreover, a sense of place underpins sustainable development goals in terms of values, cognitions, and perceptions of people and nature [6]. Thus, sense of place is important for the sustainable development of places [7]. Moreover, because of the close relationship between sense of place and “character and values” of scientific literacy, a sense of place has been viewed as important quality of citizens [8]. In addition, a study demonstrates the relationship between sense of place and social responsibility, emphasizing the critical role of sense of place in people’s overall development [9].

In view of the role sense of place plays in societal development, identifying the factors that promote a person’s sense of place has become the preoccupation of many scholars. For example, a person’s demographics, including gender, age, and psychological orientations, such as perceptions, and cognition, have been found to influence their sense of place [10,11]. Likewise, researchers have found that external factors, such as residential address and social culture, exert an even stronger impact on sense of place [12,13,14,15]. Ittelson [16] has discussed the influence of the physical environment on cognition and perception extensively, indicating that the benefits of one’s environment influences his/ her sense of place. In fact, researchers harness the therapeutic nature of the natural environments to regulate subjects’ emotions, suggesting that people’s emotions become more positive after interacting with natural environments [17]. In addition, the development of sense of place is closely related to geography education. Sense of place is considered as an important part of the fieldwork process [18]. Moreover, when students engage in geography outdoor education, they can acquire a sense of place from a range of geographic processes and meanings [19]. When students have a deeper sense of place, they also have a profound understanding of the sustainability of the local community [6]. Additionally, sense of place, a kind of geographical thinking, helps students become not only learners of geography but also thinkers of geographical ideas [20].

Many researchers have defined spatial thinking for solving geographical problems as geospatial thinking [21,22]. Geospatial thinking is the combination of three elements: spatial concepts, representational tools, and spatial reasoning [23]. These elements compose an individual’s cognition of his or her environment [24]. As an external expression of geography literacy, the value of geospatial thinking in geography education has received increased attention. Geospatial thinking, as a goal of geography education for students [25], is potentially linked to a sense of place. In a fieldwork, teachers found that students interact with different circles of the environment to judge the terrain, which contributed to the improvement of geospatial thinking and understanding of the place [26]. Also, the use of interactive devices during geography education process develops a sense of place by expanding students’ perception of space and place [27]. In addition, cognitive-emotional theory reveals a relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. Dreisbach [28] systematically argued that emotion and cognition cannot and should not be separated. Moreover, some researchers have found that emotions, cognition, and the connections between them change in specific contexts [29]. In addition, creativity includes novelty and usefulness, intrinsically relating to the sense of place [30]. Further, there is an intrinsic relationship between creativity and sense of place. The 4P model of creativity (creativity could be characterized in terms of four elements—person, press, process, and product) [31] and the investment theory of creativity (the more creative resources you have, the more creative you are) [32] point to a strong link among creativity, environment and perception. Certainly, environment and perception have an impact on the cultivation of sense of place [33]. Moreover, the link between creativity and emotions has long been confirmed [34].

Although researchers have not focused on the complex relationship among geospatial thinking, sense of place, and creativity, several existing studies provide evidence for their possible relationships. First, according to the 4P model of creativity and the investment theory of creativity [31,32], we find that human information acquisition in the environment is closely related to creativity. However, the relationship between geospatial thinking (a type of cognition about the geographical environment) and creativity (abilities to generate new ideas, discover and create new things.) has rarely been investigated. Moreover, sense of place is related to the interaction between people and environment [35,36]. However, few studies have linked geospatial thinking and sense of place. In conclusion, geospatial thinking, creativity, and sense of place may be interrelated but unexplored, and thus deserves research attention.

Therefore, in order to understand ways of developing students’ sense of place by enhancing geospatial thinking in geography education, and ways to better promote individual participation in sustainable development of places, we explored the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. Creativity is an important skill that can help students navigate uncertain futures, and that plays an important role in the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development of individuals. We further tested the mediating role of creativity and explored whether fostering geospatial thinking could facilitate individuals to generate more creative cognitive, innovative behaviors about place, which strengthened the sense of place to achieve sustainable development for both people and places together. Gender and residential address were controlled for given their potential confounding effects [37]. The next section discusses the definitions of these three constructs, their influences, and the relationships among them.

2. Theoretical Basis and Hypothesis

2.1. Geospatial Thinking and Sense of Place

The study of spatial thinking began with psychologists’ research on spatial cognitive abilities [38]. However, spatial thinking is not the same as spatial cognitive ability [39]. In Learning to Think Spatially, spatial thinking is considered to be a type of thinking that can use space to deconstruct problems, find answers, and propose solutions [23]. Geospatial thinking, as a part of spatial thinking, has the characteristics of spatial thinking [40]. Kastens [41] argues that spatial thinking in the context of Earth sciences gains meaning from operations on location and orientation. A study pointed out that geospatial thinking takes the Earth’s environment as its subject and solves geographical problems with the help of concrete spatial information rather than concepts [42]. Moreover, compared to spatial thinking, which concerns space broadly regardless of scale, geospatial thinking is more concerned with the Earth, landscape, and environmental scale dimensions [43,44]. Furthermore, geospatial thinking is concretely reflected in the process of spatial analysis and reasoning [22]. Geospatial thinking is influenced by multiple factors. Firstly, Gersmehl [45] found that there are different regions of the brain capable of different spatial thinking in the field of neuroscience. In addition, McGee [46] suggested that neurological factors, such as experience, genetics, and hormones, contribute to differences in individual spatial thinking tests. Secondly, individual characteristics, including intelligence, gender, and learning ability, also influence geospatial thinking [22,39,47]. Finally, geospatial thinking is closely related to human-environment interactions. Some researchers argue that human behavior occurs in the midst of space, and that human interaction with the surrounding environment and the processing of spatial information ends up guiding human behavior in an adaptive way [48].

In the last few decades, a large and growing body of literature has investigated sense of place. First, although the concept and terminology of sense of place is constantly changing [49], it is usually viewed as a combination of environment, perception, and emotion [50,51]. Therefore, the formation of a sense of place should take into account not only the specific location and geographic environment, but also the perception of the environment [52]. Besides, it is defined in The Dictionary of Human Geography [53] as the attitudes and feelings of an individual or group toward the geographical area they inhabit. This definition suggests that people are inextricably linked to their environment [54]. Tuan [55] found that the sense of place expressed by individuals is related to the unique characteristics of places. Moreover, place attachment [56], place dependence [57], and place identity [58] emerge as subordinate concepts of sense of place as the research continues. Similarly, sense of place can be influenced by various factors. On one hand, it is influenced by environmental factors [59], which include the physical and social environment: firstly, family residence, the natural environment, and local architectural features in the physical environment all influence the sense of place [60,61,62]; and secondly, social environment factors, such as socioeconomic status and well-being, also affect the sense of place [63]. On the other hand, personal factors also play a role. For example, recent research in neuroscience has found that personal elements, such as gender, behavioral, physical, perceptual, and emotional factors, are related to the formation of sense of place [64,65,66,67].

Combining the review of geospatial thinking and sense of place, we find that although the existing literature does not directly link sense of place and geospatial thinking, there is an implicit link between them. Firstly, a sense of place is often seen as an emotional connection between people and places [54]. Geospatial thinking is a spatial perception of the environment [23]. Cognitive-emotional theory states that people always try to conform their emotions to their cognition [68]. For example, one study found that disrupting cognitive processes leads to changes in emotional reactivity and adaptive behavior [69]. Also, the use of cognitive inhibition in patients with depression can be effective in regulating their mood [70]. Thus, cognitive-emotional theory supports a potential relation between geospatial thinking and sense of place. Secondly, there exists a close relationship between spatial thinking and sense of place. People’s perceptions of place begins with simple spatial perceptions and then gradually develop into a sense of place [71]. Moreover, spatial thinking enables people to develop a sense of place as they interact with the world around them [72]. Furthermore, spatial thinking can serve as a curricular framework to develop a sense of place [73]. It has been found that sense of place is an interaction between people and the environment [74], while geospatial thinking is the collection of information about the environment by people [75]. Moreover, when geospatial thinking is used to solve geographical problems, the first thing that is needed is the collection of relevant geographical information [76]. Thus, geospatial thinking helps individuals to better access information in their environment and enables them to better adapt to their environment. Thus, individuals use geospatial thinking to encode spatial information when interacting with their environment, which may have contributed to the development of the sense of place [77]. Therefore, we formulate hypothesis 1:

H1.

There is a positive relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Creativity

Research into creativity has a long history. Guilford defined it as the ability to generate novel and applicable ideas or products [78]. Nowadays, it is generally accepted that creativity is related to cognitive processes. In recent years, creativity has become a hot spotlight across the globe. As a bridge between the individual and society, creativity has been considered an important component of citizens’ basic literacy [79]. The OECD’s 2030 Learning Compass pointed out that creativity is the foundation of personal development [80]. Also, in China, creativity has been closely linked to the Development of Key Competencies of Chinese [81].

In addition, the importance of the classical theory of creativity cannot be overstated. Kaufman and Be Ghetto [82] proposed a model for the development of creativity—the 4C framework in which creativity is divided into four types of creative products. These are mini-c, little-c, pro-c, and big-c. They represent different kinds of efforts made by people facing different problems under different environmental pressures. The 4Ps framework of creativity is one of the best known theories of creativity [31]. In the 4P framework of creativity, creativity is considered to be described by four elements: person, press, process, and product, where press refers to the environmental forces that stimulate creative thinking and behavior. Sternberg [32] proposed a theory of creativity investment. The theory includes six creativity resources—intellectual processes, knowledge, intellectual style, personality, motivation, and environmental context. The theory considers creativity as a result of the interaction between the individual, the environment, and the specific task.

According to classical theories, such as the 4P theory of creativity and the investment theory of creativity, we can find that creativity is influenced by various factors. For example, personal factors, such as emotion, gender, motivation, and self-identity [83,84,85,86], have an impact on creativity. In addition, creativity can also be influenced by external factors, including the physical environment and social culture [87,88]. In addition, geospatial thinking may affect creativity. People with geospatial thinking are able to have a greater understanding of their environment [24], which enables them to modify their space in a novel way to make it fit for purpose. Firstly, according to creativity investment theory [32], geospatial thinking constitutes a critical cognitive resource. In other words, the more cognitive resources one has (i.e., having a high level of geospatial thinking), the more a person can modify their space in new and useful ways. Secondly, the various types of creativity products in the 4C theory of creativity are the result of learning something new in the environment [82]. Geospatial thinking, on the other hand, can help in the understanding of the environment [24], which leads to a better learning of new things. Finally, the role of environmental forces is emphasized in the 4P theory of creativity [32]. Geospatial thinking, as awareness of the environment, can serve as a resource, which, when invested in, might produce creativity.

Reviewing extant literature, we find that creativity may influence the sense of place. Firstly, the relationship between creativity and cognition has long been established [89]. Moreover, studies related to person-environment fit suggest that creativity is related to the interaction between people and their environment [90]. Moreover, what can be found is that creativity facilitates the interaction between people and the environment through the good use of information and resources in the environment [91,92]. Secondly, creativity can have an impact on human emotions [93]. For example, true creative effort is often accompanied by a strong emotional commitment and the great excitement it generates when it is realized [94]. Moreover, the creative process is often emotionally charged and the level of creativity predicts the ability to regulate emotions [95]. Therefore, we can deduce Hypothesis 2.

H2.

Creativity mediates the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place.

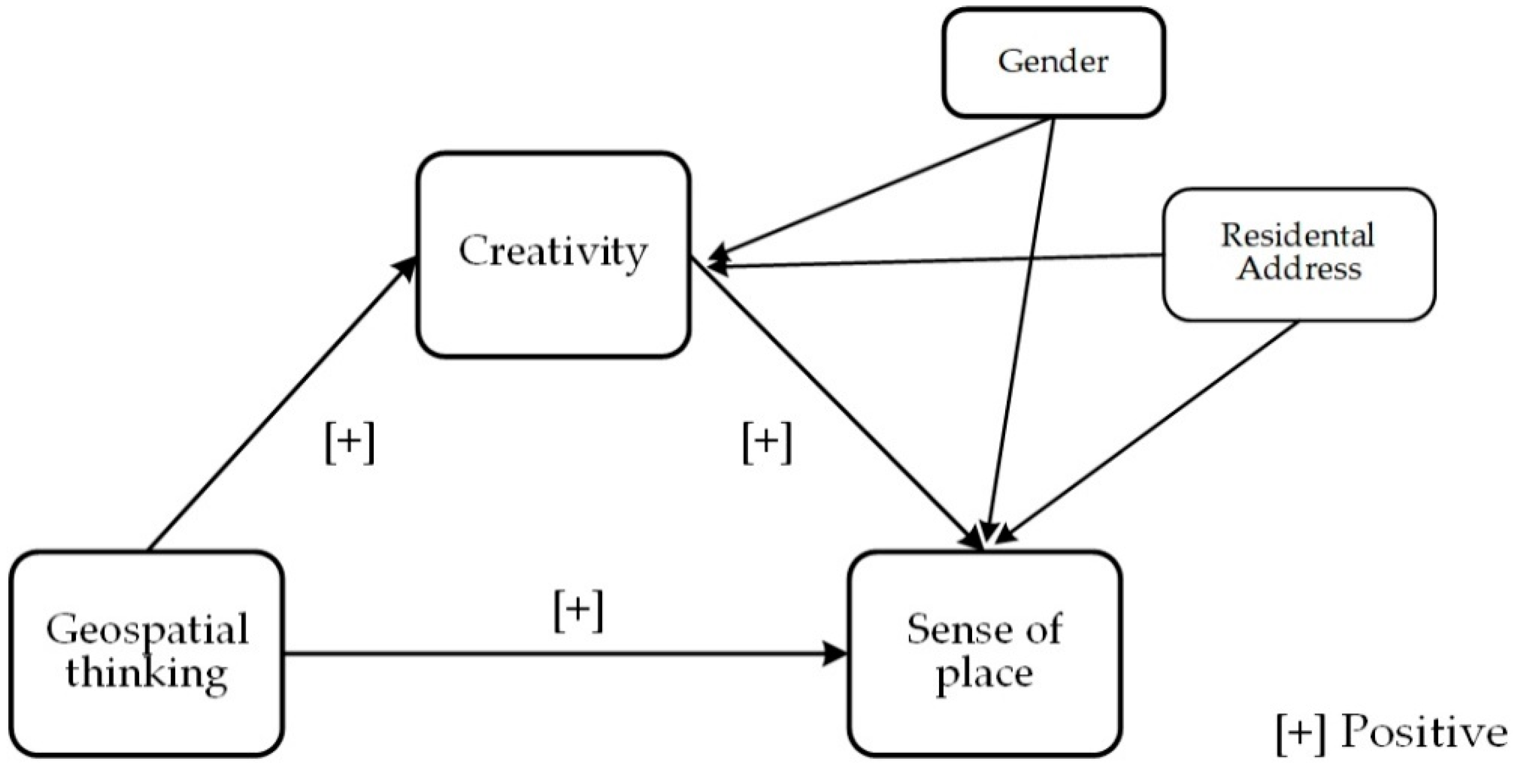

Based on the above literature reviews and hypotheses, hypothetical model sees Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The relationships examined in the study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

We collected data from public senior high schools in western China. A total of 1268 students aged 16 to 18 completed the survey between 10 June and 30 June 2022. We explained the study to their parents, headteachers, and geography teachers, and obtained consent from students and parents before completing the questionnaires. Paper questionnaires were distributed to the students during recess. After the students completed them, we collected them and digitized the data for further study. The number of valid questionnaires were 1037 after removing any incomplete responses. Among the respondents, 260 (25.072%) were male and 777 (74.928%) were female. As for the residential address, 621 students (59.884%) lived in urban areas and 416 (40.115%) in suburban areas. The statistical results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

3.2. Materials

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of four components: Demographic Information, Geospatial Thinking Test questionnaire, Sense of Place Scale, and Innovative Behavior Scale. Demographic information includes gender and residential address. In this study, three scales originally developed in English were translated into Chinese. In order to improve the accuracy of the translation, a back-translation method was used [96], which means that one researcher translated the questionnaire from English to Chinese, then a second researcher translated the Chinese version into English, and finally the third researcher compared the three versions of the questionnaire (original, translated and back-translated) to check the equivalence of the English original and the Chinese translation. Any non-equivalence was resolved before data collection.

3.2.1. Sense of Place Scale

Adapted from Jorgensen and Stedman [97], the Sense of Place Scale includes three dimensions: place dependence, place attachment, and place identity. The scale consists of 12 items, measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale: from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items included “This place, as it relates to me, is a reflection of my existence” and “This place is my favorite place to be”. After discussion, some item statements were modified to accommodate the language habits and life experiences of middle school students. In this study, the internal consistency coefficient of the scale was 0.688.

3.2.2. Innovative Behavior Scale

The Innovative Behavior Scale was adapted from Janssen [98] and consists of three dimensions: idea generation, idea promotion, and idea realization. The scale consists of nine items, including “Creating new ideas for difficult problems” (idea generation), “Mobilizing support for innovative ideas” (idea promotion), and “Transforming innovative ideas into useful applications” (idea realization). This scale is measured on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Finally, mean scores were calculated, where higher scores were more creative. In the present study, the internal consistency coefficient of the scale was 0.894.

3.2.3. Geospatial Thinking Test Questionnaire

The Geospatial Thinking Test questionnaire draws on the Spatial Thinking Ability Test (STAT) instrument developed by Bednarz [99]. The questionnaire has 16 questions of different types, such as directional judgment, map reading, map use, landform identification, and logical operations. Moreover, Bednarz and Lee have validated the reliability of the STAT scale in relevant studies in eight countries. Zhang et al. [100] translated the scale into Chinese to measure the geospatial thinking ability of high school students in the west of China and verify its applicability. Students’ geospatial thinking is scored as one point for a correct answer and no points for a wrong answer. The higher the score, the higher the level of geospatial thinking of the participating students. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.695.

3.3. Data Analysis

SPSS (version 26.0) and PROCESS plug-in (version 4.0) were used to analyze the data. To ensure the validity of the data analysis, Harman’s one-way test was conducted using principal component factor analysis to test for common method bias [101]. The results of the unrotated principal component analysis showed that ten factors had eigenvalues greater than one, and their contribution to the total variance was 53.697%. The first factor accounted for only 15.558%, far below the critical criterion of 40% [102], indicating the absence of significant common method bias. In other words, the variation between the independent and dependent variables is mainly caused by differences in the variables, rather than by the method of data collection and measurement methods. Next, descriptive statistical analyses were performed: the mean and standard deviation were calculated for each variable to observe trends in concentration and dispersion. After that, Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficients were calculated to test the correlation of all variables. Finally, the PROCESS plug-in (version 4.0) was used to test the mediation model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive analysis of geospatial thinking, creativity, and sense of place. Geospatial thinking has a mean value of 8.4300 and a standard deviation of 2.708. The mean value of creativity was 2.643, with a standard deviation of 0.725. The mean value of sense of place was 3.370, with a standard deviation of 0.480.

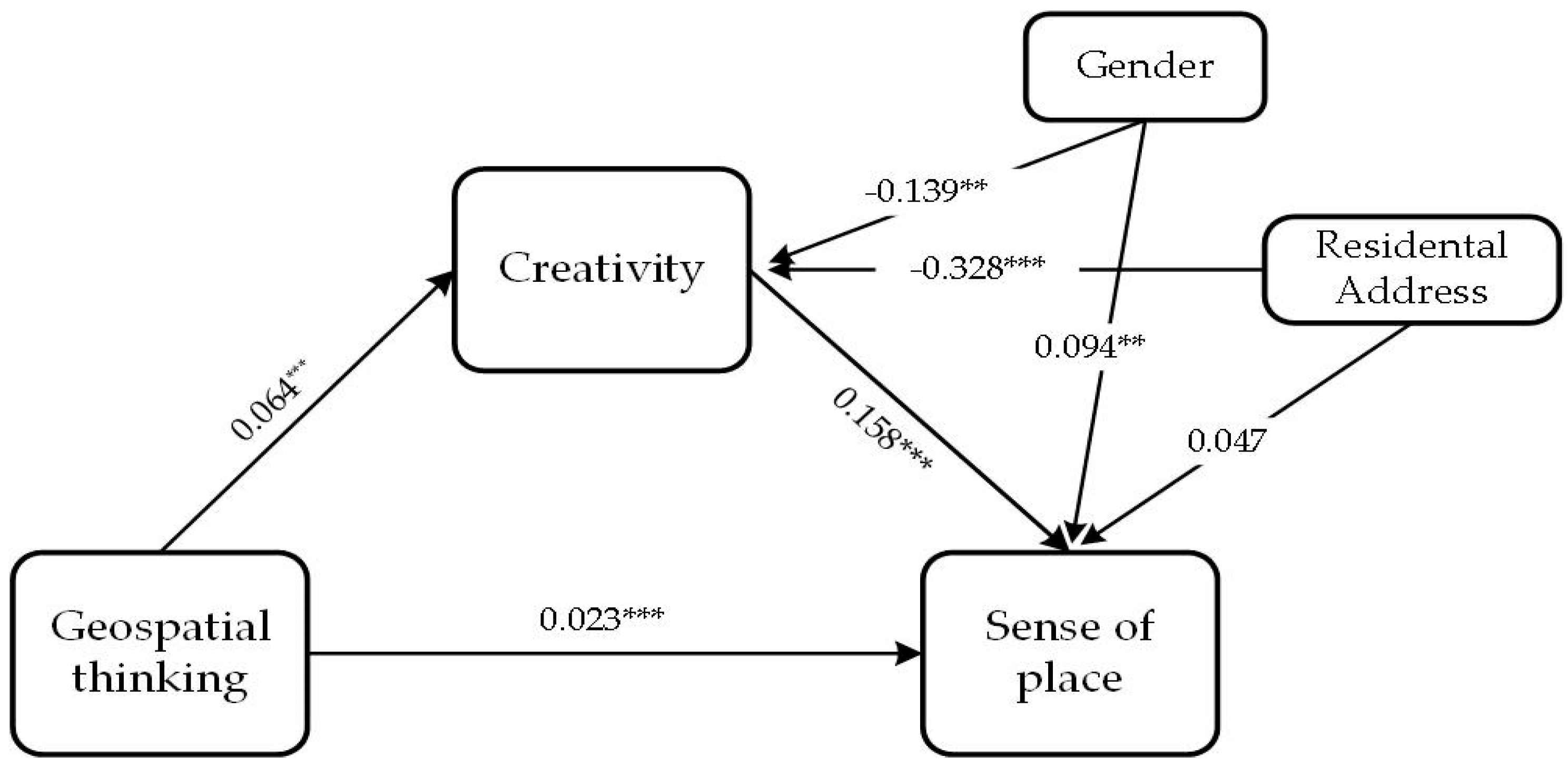

The closeness of the relationship between the variables was assessed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient. The results showed (as shown in Figure 2) that all three variables were positively correlated with each other. Geospatial thinking was found to have a significant positive correlation with sense of place (r = 0.185, p < 0.001). There was a significant positive correlation between geospatial thinking and creativity (r = 0.278, p < 0.001). A positive correlation between creativity and sense of place (r = 0.253, p < 0.001) was also significant. The correlation results are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The mediation model showing relationships between Geospatial Thinking and Sense of Place and the mediating role of Creativity (** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis.

4.2. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS plug-in (version 4.0). Geospatial thinking was used as the independent variable, sense of place was used as the dependent variable, and creativity was used as the mediating variable (Model 4). Based on the influence of gender and family residence on an individual’s sense of place [37], these variables were controlled for in this study.

The results showed (as shown in Table 3) that geospatial thinking significantly predicted sense of place (β = 0.033, t = 5.982, p < 0.001) and that the results remained significant even when creativity was entered (β = 0.023, t = 4.141, p < 0.001). In addition, geospatial thinking was found to positively predict creativity (β = 0.064, t = 8.056, p < 0.001). Creativity had a positive effect on sense of place (β = 0.158, t = 7.459, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis.

As can be seen in Table 3, both gender and family residence have an effect on sense of place when exploring the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. Firstly, gender had a significant effect on sense of place (β = 0.072, t = 2.119, p < 0.05) while family residence did not. The effect of gender on sense of place was significantly increased by including creativity in the model (β = 0.094, t = 2.827, p < 0.01), but there was still no significant relationship between family residence and sense of place. Figure 2 provides a graphic representation of these relationships.

Furthermore, the confidence intervals (95%) for both the direct effect of geospatial thinking on sense of place and the mediating effect of creativity did not contain 0 (see Table 4). This suggests that geospatial thinking can predict sense of place directly, and indirectly through creativity after controlling for gender and family residence variables. The direct effect (0.023) and the mediating effect (0.010) accounted for 69.697% and 30.303% of the total effect, respectively.

Table 4.

Total, direct and indirect effects among the variables.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of the Results

In this study, a mediation model was developed to explore the relationship between geospatial thinking, sense of place and the mediating role of creativity. Based on the proposed hypotheses, this study discusses the findings in terms of (1) the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place, and (2) the mediating role of creativity in the link between geospatial thinking and sense of place.

Firstly, the results of this study suggest a significant positive correlation between geospatial thinking and sense of place, which is similar to some previous studies. For example, the results of one study suggest that geospatial thinking underpins the development of sense of place and has an important role in place awareness in the sense of place [103]. One possible reason about the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place is that they are closely related in the field of neuroscience [45,64]. For instance, both human cognition and emotion are influenced by the parietal cortex, which is a part of the brain [104,105]. Moreover, geospatial thinking and sense of place can be influenced by both environmental and individual factors, which is one of the possible reasons [43,63]. The formation of sense of place is affected by perception [52], and geospatial thinking is the perception and processing of spatial information by people in space [106]. In addition, existing research has confirmed the importance of spatial cognition as a component of geospatial thinking [23], which is involved in the formation and development of sense of place [65]. Overall, there is a close relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place, which is reflected not only in their influencing factors, but also in their interactions. The enhancement of geospatial thinking leads to better awareness and perception of the environment, and sense of place is precisely considered to be a combination of cognition and environment. Therefore, geospatial thinking positively affects sense of place.

Secondly, creativity mediates the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. To begin with, geospatial thinking has a positive predictive effect on creativity. Geospatial thinking is the basis for people’s cognition and perception of the environment and space [43]. Both creativity investment theory and the 4Ps model of creativity suggest that creativity is the result of the interaction between an individual’s perception and the environment [32]. Additionally, there is psychological evidence that creativity is closely related to the senses and perception [107]. Therefore, we can say that the better one’s geospatial thinking, the better one’s creativity. We were able to draw some conclusions that geospatial thinking and creativity are intrinsically linked. The environment and perception are important factors in the connection between geospatial thinking and creativity, and the interaction between people and the environment facilitates their intersection [108].

Furthermore, creativity plays a positive role on sense of place. Creativity is often thought to be influenced by both the environment and individual perception [109,110]. Some studies have found that positive environments have a facilitating effect on creativity, whether in natural and social settings [111]. In addition, Maslow’s [107] study demonstrated that sensory stimuli and perceptual systems influence creative behavior. Additionally, studies have found that positive perceptions and emotions have a favorable effect on creativity [112]. Sense of place has long been considered as a combination of environment and perception [51]. Thus, environment and perception provide the link between creativity and sense of place. Moreover, research on the 4C model of creativity [82] provides support for this conclusion. The mini-c and little-c can be transformed into pro-c and big-c when subjected to specific environmental stimuli [113]. Our interpretation of this result is that when the surrounding environment affects a person’s perception, his creativity changes as a response. Subsequently, as a result of such a change, he develops a different attitude towards the particular environment, resulting in a change in his sense of place.

Additionally, geospatial thinking can have an impact on sense of place through the mediating role of creativity. Recently, theories have emerged in neuroscience suggesting that complex mental structures, such as creativity, are not restricted to one brain region [114]. Part of the view of localization on cognitive function is that the right hemisphere of the brain dominates spatial cognition [115], which is an crucial component of geospatial thinking. In addition, it has also been suggested that, under certain circumstances, brain regions respond selectively to a given category of emotions [116]. This means that different emotions cause different areas of the brain to respond. Thus, the action regions of the brain for creativity, geospatial thinking, and sense of place may overlap in some cases. In this way, we can say that the three are closely related in the field of neuroscience. Moreover, it is reasonable to speculate that creativity, as a complex mental structure, can connect geospatial thinking and sense of place, and act as a mediating link between them.

Thirdly, the findings suggest that differences in gender predict differences in creativity. Our findings suggest that creativity is higher among boys in our study, which is consistent with several existing studies [117]. One possible explanation is that men have better emotional skills and emotion regulation than women [118]. Indeed, the gender inequality of respondents may have an impact on this result and warrants further research. In addition, the results showed a significant correlation between residence and student creativity, similar to some previous studies [119]. This may be because students living in urban areas have better family capital to support students’ creative behaviors [120]. Finally, the results of the study also indicated that respondents from the countryside possessed a better sense of place. This may be due to the unique and sensual vernacular landscape that arises in the countryside, which provides a good basis for students’ sense of place development [121]. Another possible reason is that geographical proximity is a key factor in human activity, and proximity between people and places in rural areas gives students good sense of place [122,123].

Based on the above discussion, we can conclude that creativity plays a mediating role in geospatial thinking and sense of place. In the current study, it is worth noting that creativity only partially mediates the relationship between spatial thinking and sense of place. Data analysis showed that geospatial thinking accounted for most of the variance in sense of place (69.697%), indicating that the mediating role of creativity was not dominant (30.303%). In other words, although high levels of creativity can affect sense of place to some extent because of geospatial thinking, geospatial thinking still plays an important and positive role in sense of place.

5.2. Implications

The present study provides a novel direction in understanding the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. The findings deepen our understanding of the broad relationship between cognition of and emotions towards environment. Also, the study extends the existing research on creativity by demonstrating its amplifying effects of geospatial thinking on one’s sense of place, advancing knowledge about the intervening mechanisms between geospatial thinking and sense of place.

In terms of practical significance, our work provides an important perspective on the potential role of geography education in students’ geospatial thinking. In line with previous work [37], our results indicate the close association between geography education and sense of place. To enhance students’ sense of place, geography teachers could implement specific teaching strategies and methods to help them improve geospatial thinking skills, promoting interaction between students and the place. For example, students need to process spatial information to solve specific geographic problems in real-world contexts during fieldwork. This promotes students’ perception of the local environment and enhances their sense of place. Finally, the mediating role of creativity may help geography education researchers understand that teaching spatial thinking through geography may inspire more creative behaviors of students. They may actively encourage students to experience and reflect on the meaning of the place comprehensively, developing a stronger sense of place and more pro-environmental behaviors. For instance, teachers can guide students to use geospatial thinking to analyze the area, gaining a special understanding of the region. At this point, creativity, as an advanced cognition, can promote more innovative ideas and behaviors to solve real problems (e.g., make a geographic model of a “sponge city”), which could enhance interactions between students and the place, inspiring them to creatively participate in the process of building a sustainable local environment.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

While this research has its strengths, it also has some limitations. Firstly, this study is a cross-sectional study, and therefore causal interpretations cannot be deduced. Secondly, all participants were from the western region of China, which may weaken the generalizability of the findings. Thirdly, the unbalanced gender ratio of the participants may also affect the generalizability of the results. In the future, researchers could use a longitudinal survey design that collects data over a period of time and recruit participants from different schools in different regions. In addition, they could examine which specific aspects of geospatial thinking, creativity, and sense of place are linked. Although the mechanisms involved in environmental cognition and environmental emotion remain controversial, the present study could provide empirical evidence and a new profile for future researchers.

6. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate a significant relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. We have shown that geospatial thinking is an important predictor of sense of place, and, additionally, creativity is a beneficial mediator of the relationship between geospatial thinking and sense of place. This means that the generation of a sense of place can be facilitated not only directly by strengthening students’ geospatial thinking, but also through the mediation of creative behaviors. The findings make a strong case for developing the geospatial thinking of students to enhance their creative behaviors, thereby promoting a healthy sense of place. Also, these results help better improve geography curricula, highlighting the importance of cultivating geospatial thinking to enhance students’ sense of place based on geography education, which provides important insights about how to promote students’ engagement in sustainable development of local places.

Author Contributions

J.G. and J.Z. contributed to the study conception and design. J.G., J.Z., Z.W., C.O.A. and X.L. contributed to data collection, data management, statistical analysis, interpretation of the results, and revision of the manuscript. J.G., J.Z. and Z.W. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2022 Key Projects of Zhejiang Province Soft Science Research Program, grant number 2022C25004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Before the survey, parents, teachers, and students received informed consent, and the ethics committee of Zhejiang Normal University approved all the process of the present study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the students who completed the questionnaire for their contributions to our research. We would also like to thank those who assisted with language revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- O’Leary, J.F.; Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1976, 34, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W.M.; Eanes, F.R.; Ulrich-Schad, J.D.; Burnham, M.; Church, S.P.; Arbuckle, J.G.; Cross, J.E. Trouble with Sense of Place in Working Landscapes. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The Relations between Natural and Civic Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clermont, H.J.; Dale, A.; Reed, M.G.; King, L. Sense of Place as a Source of Tension in Canada’s West Coast Energy Conflicts. Coast. Manag. 2019, 47, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V.A.; Stedman, R.C.; Enqvist, J.; Tengö, M.; Giusti, M.; Wahl, D.; Svedin, U. The Contribution of Sense of Place to Social-Ecological Systems Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-T.; Shein, P.P. Developing Sense of Place through a Place-Based Indigenous Education for Sustainable Development Curriculum. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Ko, Y.; Lee, H. The Effects of Community-Based Socioscientific Issues Program (SSI-COMM) on Promoting Students’ Sense of Place and Character as Citizens. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2020, 18, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casakin, H.; Billig, M. Effect of Settlement Size and Religiosity on Sense of Place in Communal Settlements. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of Place in Developmental Context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P. Effects of Sense of Place on Responses to Environmental Impacts: A Study among Residents in Svalbard in the Norwegian High Arctic. Appl. Geogr. 1998, 18, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogan, K. A Sense of Place: The Politics of Immigration and the Symbolic Construction of Identity in Southern California and the New York Metropolitan Area. In Sociological Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 17, pp. 223–253. [Google Scholar]

- Shamai, S.; Ilatov, Z. Measuring Sense of Place: Methodological Aspects. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. A Sense of Place: Place, Culture and Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracuzzi, N.F. Youth Aspirations and Sense of Place in a Changing Rural Economy: The Coos Youth Study; The Carsey School of Public Policy at the Scholars’ Repository: Durham, NH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ittelson, W.H. Environment and Cognition; Seminar Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, S.Å.K.; Rydstedt, L.W. Active Use of the Natural Environment for Emotion Regulation. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattchow, B.; Higgins, P. Through Outdoor Education: A Sense of Place on Scotland’s River Spey. In The Socioecological Educator; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Marvell, A.; Simm, D. Unravelling the Geographical Palimpsest through Fieldwork: Discovering a Sense of Place. Geography 2016, 101, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, A.P. Using “Autogeography,” Sense of Place and Place-Based Approaches in the Pedagogy of Geographic Thought. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Lu, X.; Du, F.; Wang, J.; Ju, B. Influencing Factors of Middle School Students’ Spatial Thinking Ability: A Case Study on Senior One Students of Baiyin No. 1 Middle School in Gansu Province. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 853–863. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y.; Wan, J.; Lu, X. The Factors and Mechanisms That Influence Geospatial Thinking: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J. Geogr. 2021, 120, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Support for Thinking Spatially. Learning to Think Spatially; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, B.W.; Johnston, M.P. Geospatial Thinking of Information Professionals. J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 54, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.M. Development of Evaluation Items for Spatial Thinking with Geography Classroom Assessment. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2011, 19, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, B.J.; Skop, E. The Silverton Field Experience: A Model Geography Course for Achieving High-Impact Educational Practices (HEPs). J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daws, S. A Sense of Place through Interactive Devices?: Utilising the Creative Opportunities of GPS and GIS Technologies to Enhance Student Understanding of Place. Geogr. Educ. 2012, 25, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach, G. Using the Theory of Constructed Emotion to Inform the Study of Cognition-Emotion Interactions. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2022, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lench, H.C.; Darbor, K.E.; Berg, L.A. Functional Perspectives on Emotion, Behavior and Cognition. Behav. Sci. 2013, 3, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runco, M.A.; Jaeger, G.J. The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, M. An Analysis of Creativity. Phi Delta Kappan 1961, 42, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. An Investment Theory of Creativity and Its Development. Hum. Dev. 1991, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-Q.; Deng, W.; Yan, J.; Tang, X.-H. The Influence of Multi-Dimensional Cognition on the Formation of the Sense of Place in an Urban Riverfront Space. Sustainability 2019, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, E.; Sundar, S.S. Can Video Games Enhance Creativity? Effects of Emotion Generated by Dance Dance Revolution. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is It Really Just a Social Construction?: The Contribution of the Physical Environment to Sense of Place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kou, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Jing, H.; Lin, P. Predictive Analysis of the Pro-Environmental Behaviour of College Students Using a Decision-Tree Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liang, X.; An, Z.; Xu, Y. The Mediating and Buffering Effect of Creativity on the Relationship Between Sense of Place and Academic Achievement in Geography. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 918289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, R.N.; Metzler, J. Mental Rotation of Three-Dimensional Objects. Science 1971, 171, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, T. Geospatial Thinking and Spatial Ability: An Empirical Examination of Knowledge and Reasoning in Geographical Science. Prof. Geogr. 2013, 65, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K. Geospatial Thinking of Undergraduate Students in Public Universities in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kastens, K.A.; Pistolesi, L.; Passow, M.J. Analysis of Spatial Concepts, Spatial Skills and Spatial Representations in New York State Regents Earth Science Examinations. J. Geosci. Educ. 2014, 62, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, T.T.; van der Schee, J.A. The Effects of Geography Lessons with Geospatial Technologies on the Development of High School Students’ Relational Thinking. Comput. Educ. 2014, 76, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzin, A.M.; Fu, Q.; Kulo, V.; Peffer, T. Examining the Effect of Enactment of a Geospatial Curriculum on Students’ Geospatial Thinking and Reasoning. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2014, 23, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell-Carrera, C.; Saorin, J.; Hess-Medler, S. A Geospatial Thinking Multiyear Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersmehl, P.J.; Gersmehl, C.A. Wanted: A Concise List of Neurologically Defensible and Assessable Spatial-Thinking Skills. Res. Geogr. Educ. 2006, 8, 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, M.G. Human Spatial Abilities: Psychometric Studies and Environmental, Genetic, Hormonal and Neurological Influences. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, Y. Measurement of Geospatial Thinking Abilities and the Factors Affecting Them. Geogr. Rep. Tokyo Metrop. Univ. 2015, 50, 131061153. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T. Spatial Thinking, Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Awareness. Cogn. Process. 2021, 22, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Clayton, S. Introduction to the Special Issue: Place, Identity and Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T. Changing Places: The Role of Sense of Place in Perceptions of Social, Environmental and Overdevelopment Risks. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space And Place: The Perspective of Experience. Leonardo 1978, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. A Global Sense of Place. In The Cultural Geography Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, D.; Johnston, R.; Pratt, G.; Watts, M.; Whatmore, S. The Dictionary of Human Geography, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place Attachment through Sensory-Rich, Emotion-Generating Place Experiences in Rural Tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Place: An Experiential Perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of Place amongst Adolescents and Adults in Two Rural Australian Towns: The Discriminating Features of Place Attachment, Sense of Community and Place Dependence in Relation to Place Identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; Freeman, C.; Carter, L.; Pedersen Zari, M. Sense of Place and Belonging in Developing Culturally Appropriate Therapeutic Environments: A Review. Societies 2020, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Corona, Y. Latin American Transnational Children and Youth Experiences of Nature and Place, Culture and Care Across the Americas; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. A Form of Affection: Sense of Place and Social Structure in the Chinese Courtyard Residence. J. Inter. Des. 2006, 32, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaab, S.A.-O.; Shuhana, S.; Nahith, T.A.-Q. A Review Paper on the Role of Commercial Streets’ Characteristics in Influencing Sense of Place. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 2825–2839. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Religion and Place Attachment: A Study of Sacred Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, A. Rethinking Sense of Place: Sense of One and Sense of Many. In Rethinking Place Branding; Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengen, C.; Kistemann, T. Sense of Place and Place Identity: Review of Neuroscientific Evidence. Health Place 2012, 18, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokowski, P.A. Languages of Place and Discourses of Power: Constructing New Senses of Place. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Anhui Baomu in Shanghai: Gender, Class and a Sense of Place. In Locating China; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. The Cognition-Emotion Debate: A Bit of History. Handb. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 5, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Smith, C.A. Knowledge and Appraisal in the Cognition—Emotion Relationship. Cogn. Emot. 1988, 2, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joormann, J. Cognitive Inhibition and Emotion Regulation in Depression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metoyer, S.K. Geospatial Technology to Enhance Spatial Thinking and Facilitate Processes of Reasoning. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tufail, A. Spatial Skills in Low-Cost Schools in Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Anthamatten, P. Spatial Thinking Concepts in Early Grade-Level Geography Standards. J. Geogr. 2010, 109, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Shariff, M.K.B.M. The Concept of Place and Sense of Place in Architectural Studies. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 5, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Janelle, D.G. Toward Critical Spatial Thinking in the Social Sciences and Humanities. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, N.T.; Sharpe, B. An Assessment Instrument to Measure Geospatial Thinking Expertise. J. Geogr. 2013, 112, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCunn, L.J.; Gifford, R. Place Imageability, Sense of Place, and Spatial Navigation: A Community Investigation. Cities 2021, 115, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms. In Handbook of Creativity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beghetto, R.A. Teaching Creative Thinking in K12 Schools. In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Teaching Thinking; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030—Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Xi, J. China Daily. Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report at 19th CPC National Congress. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-11/04/Content_34115212.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Kaufman, J.C.; Beghetto, R.A. Big and Little: The Four c Model of Creativity. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussi, K.S.; Randel, A.E.; Dionne, S.D. I Am, I Think I Can, and I Do: The Role of Personal Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Cross-Application of Experiences in Creativity at Work. Creat. Res. J. 2007, 19, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, J.S.; Chamberlin, S.A.; Mann, E. Factors That Influence Mathematical Creativity. Math. Enthus. 2019, 16, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.; Lee, J. Effects of Robotics Programming on the Computational Thinking and Creativity of Elementary School Students. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, T.P.; Neuvonen, M.; Korpela, K.M. The Psychology of Recent Nature Visits:(How) Are Motives and Attentional Focus Related to Post-Visit Restorative Experiences, Creativity, and Emotional Well-Being? Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 913–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Fan, C.; Aboagye, M.O.; Brobbey, P.; Jababu, Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Avornyo, P. Job Demand Stressors and Employees’ Creativity: A within-Person Approach to Dealing with Hindrance and Challenge Stressors at the Airport Environment. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 250–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Shan, C.; Yu, H. The Relationship between the Feedback Environment and Creativity: A Self-Motives Perspective. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Du, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. The Effect of Virtual-Reality-Based Restorative Environments on Creativity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.N. Person–Environment Fit and Creative Behavior: Differential Impacts of Supplies–Values and Demands–Abilities Versions of Fit. Hum. Relat. 2004, 57, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Ruiz, D.; Ostad-Ahmad-Ghorabi, H. Influence of Environmental Information on Creativity. Des. Stud. 2010, 31, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y. Creative Entrepreneurs’ Guanxi Networks and Success: Information and Resource. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-Y.; Chuah, C.-Q.; Lee, S.-T.; Tan, C.-S. Being Creative Makes You Happier: The Positive Effect of Creativity on Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, M. Emotion and Creativity. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2004, 38, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z.; Brackett, M.A. Predicting Creativity: Interactive Effects of Openness to Experience and Emotion Regulation Ability. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners Attitudes toward Their Properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job Demands, Perceptions of Effort-reward Fairness and Innovative Work Behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarz, R.; Lee, J. What Improves Spatial Thinking? Evidence from the Spatial Thinking Abilities Test. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2019, 28, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Su, T.; Li, X.; Ge, J.; An, Z.; Xu, Y. The Mediating Effect of Geospatial Thinking on the Relationship between Family Capital and Sense of Place. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 918326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting Common Method Bias: Performance of the Harman’s Single-Factor Test. ACM SIGMIS Database Adv. Inf. Syst. 2019, 50, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, A.; Liston, J. Developing Spatial Thinking with Journey Sticks. Teach. Geogr. 2020, 45, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, A.; Büchel, C.; Gross, J.J. The Neural Bases of Emotion Regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, J. From Thought to Action: The Parietal Cortex as a Bridge between Perception, Action and Cognition. Neuron 2007, 53, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, R.; Marsh, M.; Battersby, S. A Conceptual Framework for Facilitating Geospatial Thinking. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2008, 98, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Creativity in Self-Actualizing People; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, J.; Giusti, M.; Haga, A.; Wallhagen, M.; Barthel, S. Enabling Relationships with Nature in Cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasniewska, J.; Necka, E. Perception of the Climate for Creativity in the Workplace: The Role of the Level in the Organization and Gender. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2004, 13, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.J.; Somer, E. Empathy, Emotion Regulation and Creativity in Immersive and Maladaptive Daydreaming. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 2020, 39, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandler, C.; Riemann, R.; Angleitner, A.; Spinath, F.M.; Borkenau, P.; Penke, L. The Nature of Creativity: The Roles of Genetic Factors, Personality Traits, Cognitive Abilities, and Environmental Sources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csizmadia, P.; Czigler, I.; Nagy, B.; Gaál, Z.A. Does Creativity Influence Visual Perception?—An Event-Related Potential Study With Younger and Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohman, M. Teaching for Creativity: Mini-c, Little-c and Experiential Learning in College Classroom. Nauki Wych. Stud. Interdyscyplinarne 2018, 7, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaufman, S.B.; Gregoire, C. Wired to Create: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind; Penguin: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-H.; Kim, K.K.; Hahm, J. Neuro-Scientific Studies of Creativity. Dement. Neurocognit. Disord. 2016, 15, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, K.A.; Wager, T.D.; Kober, H.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Barrett, L.F. The Brain Basis of Emotion: A Meta-Analytic Review. Behav. Brain Sci. 2012, 35, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, G.; Dewi, S.M.; Herayanti, L.; Lestari, P.A.S.; Fathoroni, F. Gender Influence on Students Creativity in Physics Learning with Virtual Laboratory. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1471, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, K.; Das, S.; Delavallade, C.; Ketema, T.; Rouanet, L. Gender Differences in Socio-Emotional Skills and Economic Outcomes; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Motalebi, G.; Parvaneh, A. The Effect of Physical Work Environment on Creativity among Artists’ Residencies. Facilities 2021, 39, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözbilir, F. The Interaction between Social Capital, Creativity and Efficiency in Organizations. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 27, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, T.P.; Tyrväinen, L.; Korpela, K.M. The Relationship between Perceived Health and Physical Activity Indoors, Outdoors in Built Environments, and Outdoors in Nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2014, 6, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.-C.-B.; Wen, T.-H. Geographically Modified PageRank Algorithms: Identifying the Spatial Concentration of Human Movement in a Geospatial Network. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Leung, H.; Jiang, H.; Zheng, H.; Ma, L. Incorporating Human Movement Behavior into the Analysis of Spatially Distributed Infrastructure. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).