Sustainability Factors of Self-Help Groups in Disaster-Affected Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Enterprises and Sustainability Measurement

3. Sustainability Indicators of Self-Help Groups

4. Data and Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity

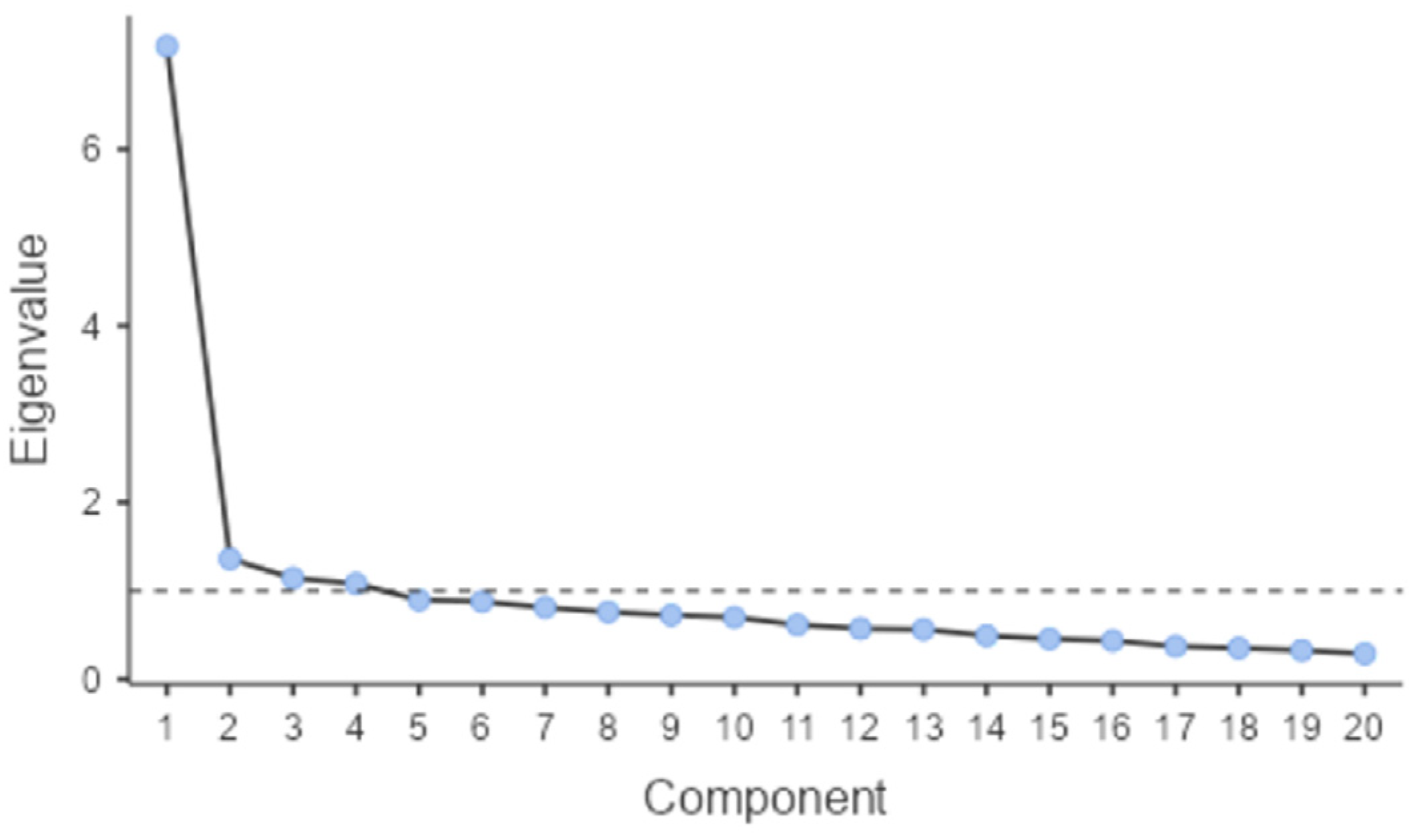

5.2. Sample Adequacy and Eigenvalues

6. Discussion

- Component 1—Audit, Resource Mobilization, Training, Planning–Monitoring–Evaluation (henceforth termed as Managerial Functions)

- Component 2—Cash Handling, Participation in Decision-Making (henceforth termed as Trust)

- Component 3—Size and Rotation of Common Fund (henceforth termed as Fund Utilization)

- Component 4—Literacy, Participation in Community Programs, Easy Access to Loans (henceforth termed as Easy Financing)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| 1 | Village name | ||||

| 1.1 | Block | ||||

| 1.2 | District | ||||

| 1.3 | Respondent name | ||||

| 1.4 | Name of family head | ||||

| 1.5 | Address | ||||

| 1.6 | Mobile no. | ||||

| 1.7 | Name of SHG | ||||

| 1.8 | Membership date | ||||

| 1.9 | Role in SHG (past and present), e.g., member, team leader, cashier, etc. | ||||

| 1.10 | Educational qualifications | ||||

| 1.11 | Occupation | ||||

| Occupation | Code | Occupation | Code | ||

| Own farm (agri) activities | 1 | Driver/boating/shipping related | 12 | ||

| Agricultural labour | 2 | Salaried employment (govt.) | 13 | ||

| Non-agricultural labour | 3 | Salaried employment (non-government) | 14 | ||

| Animal rearing | 4 | Migrant workers (seasonal) | 15 | ||

| Fishery | 5 | Migrant workers (whole year) | 16 | ||

| Trade of fish | 6 | Household activities (paid) | 17 | ||

| Petty trade/business | 7 | Household activities (unpaid) | 18 | ||

| Trade/business of forest products | 8 | Pension holder | 19 | ||

| Collection of non-timber forest products and sale | 9 | Doing nothing (old age, illness, disability) | 20 | ||

| Pottery/handicraft | 10 | Studying | 21 | ||

| Masonry worker | 11 | Other | 22 | ||

| 2.1 | SHG established year | |

| 2.2 | SHG work area | |

| 2.3 | What inconveniences are faced? (1.) What are the natural disasters, such as droughts or storms, faced? In what way did it create obstacles to SHG work? 2. What are the administrative obstacles faced? | |

| 2.4 | What kind of work or initiatives does the SHG support, and who gets help? | |

| 2.5 | What kind of work was done by you, and when? | |

| 2.6 | What are the socioeconomic changes brought by the SHG? (Change means: going to school, economic improvement, govt. assistance with projects, maternity care and benefits, etc.) |

| The importance of an SHG’s properties response | |

| 3.1 | Size of the SHG plays an important role ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.2 | Economically weaker members make group work easy ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.3 | Meeting every week ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.4 | The attendance rate per meeting should be high ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.5 | All members should participate in decision-making ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.6 | All members should equally share responsibility ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.7 | Rules and regulations are important for the group ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.8 | Savings is important ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.9 | Easy access to loans is good for the group ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.10 | All members must participate in loan repayment ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.11 | Rotation of the common fund is required ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.12 | Idle capital is not good for the group ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.13 | Cash handling can be done by any member ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.14 | Resource mobilization in one place is good for the group ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.15 | Bookkeeping and financial documentation are important ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.16 | Auditing is important ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.17 | Training programs are critical for group functioning ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.18 | Planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the program by group members is important ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.19 | Participation in community programs is essential for group functioning ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

| 3.20 | Literacy is important for the group ☐ Strongly agree ☐ Agree ☐ Neutral ☐ Disagree ☐ Strongly disagree |

References

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations General Assembly, Development and International Co-Operation Environment: Oslo, Norway, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Viederman, S. Five Capitals and Three Pillars of Sustainability. Newsl. PEGS 1994, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Warhurst, A. Sustainability Indicators and Sustainability Performance Management; Warwick Business School: Coventry, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, P. A Conceptual Framework for Environmental Analysis of Social Issues and Evaluation of Business Response Patterns. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 4, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamburia, G. Sustainability of Social Enterprises: A Case Study of Sweden. Master’s Thesis, KTH Industrial Engineering and Management, Stockholme, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.B.; Anderson, B. For-Profit Social Ventures. In Social Entrepreneurship; Senate Hall Academic Publishing: Dublin, Ireland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange, D.E.; Busch, T.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Sustaining Sustainability in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S. Viability of social enterprises: The spillover effect. Soc. Enterp. J. 2012, 8, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, P. Social enterprise sustainability revisited: An international perspective. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, M.; Lerner, M.; Yitshaki, R. Long-term Survivability of Social Ventures: Qualitative analysis of External and Internal Explanations. In International Perspectives of Social Entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, M. Growing the social enterprise—Issues and challenges. Soc. Enterp. J. 2009, 5, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassa, J.A. Roles of Non-Government Organizations in Disaster Risk Reduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burkett, I. Sustainable Social Enterprise—What Does It Really Mean? Foresters Community Finance: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harik, R.; El Hachem, W.; Medini, K.; Bernard, A. Towards a holistic sustainability index for measuring sustainability of manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 4117–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, K.; Dawans, V. The Integrated Approach to Social Entrepreneurship: Building High Performance Organizations. Soc. Enterp. Report. SER 2006, 204, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organisations: A Review and Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K. Indicators and Variables. Available online: https://www.janda.org/c10/Research%20papers/indicators.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Thapa, B.; Chalmers, J.; Taylor, W.; Conroy, J. Banking with the Poor. Report and Recommendations Prepared by Lending Asian Banks and Nongovernmental Organizations; Foundation for Development Cooperation: Brisbane, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot, D.; Bapat, V. Contributory Factors Towards Sustainability of Bank- Linked Self-Help Groups in Indi. Asia-Pac. Sustain. Dev. J. 2019, 26, 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gallopın, G. Indicators and their use: Information for decision making. In Sustainability Indicators: Report of the Project on Indicators of Sustainable Development; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Sustainability measurement system: A reference model proposal. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 438–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Guha, P. Measuring Women’s Self-Help Group Sustainability: A Study of Rural Assam. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2019, 15, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R. Self-Help Groups in India. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, P.C.; Sinha, A. Performance and sustainability of self-help groups in India: A gender perspective. Asian Dev. Rev. 2010, 27, 80–103. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Y.K.; Kaushal, S.K.; Gautam, S.S. Performance of women self-help groups (SHGs) in Moradabad district, Uttar Pradesh. Int. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 14, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Veleva, V.; Ellenbecker, M. Indicators of sustainable development: Framework and. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Frost, G. Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Account. Forum 2008, 32, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Osborne, S. Can Marketting Contribute to Sustainable Social Enterprises? Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 11, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, P.; Ramakumar, R. Micro-credit and rural poverty: An analysis of empirical evidence. Econ. Political Wkly. 2002, 37, 955–965. [Google Scholar]

- Purnima, K.S.; Narayanareddy, G.V. Indicators of effectiveness of women self-help groups in Andhra Pradesh. J. Res. (ANGRAU) 2007, 35, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, H.; Seibel, H. Commercial Aspects of Self-Help Group Banking in India: A Study of Bank Transaction Costs; University of Cologne; Development Research Center: Koln, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, N. Revisiting bank-linked self help groups (SHGs)—A study of Rajasthan State. In Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers; Reserve Bank of India: Kolkata, India, 2007; Volume 28, pp. 125–156. [Google Scholar]

- ARAVALI. Quality and Sustainability of SHGs—A Study of Rajasthan; NABARD: Jaipur, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- NCAER. Impact and Sustainability of SHG Bank Linkages Programme; National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER): New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Malathi, N. Micro Credit and Rural Development. In Micro-Credit and Rural Development; Deep & Deep Publication: New Delhi, India, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, K.N.; Madheswaran, S. Whether Micro Finance Groups Are Sustainable? Evidence from India. In Proceedings of the Conference of the All India Econometric Society, Hyderabad, India, 3–5 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.O.; Tripathy, L. Women’s Collectives as Vehicles of Empowerment and Social Change: Case study of Women’s Self Help Groups in Odisha, India. St Antony’s Int. Rev. 2020, 16, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, P.T.; Kline, P. The observation to variable ratio in factor analysis. Personal. Study Group Behav. 1981, 1, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scientific Use of Factor Analysis in Behavioral and Life Sciences; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. Psychometrics and Psychology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rahn, M. Factor Analysis: A Short Introduction, Part 5—Dropping Unimportant Variables from Your Analysis. The Analysis Factor. Available online: https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/factor-analysis-5/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Bryant, F.B.; Yarnold, P.R. Principal components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics; Grimm, L.G., Yarnold, R.R., Eds.; American Psycholgical Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zach. A Guide to Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. 22 April 2019. Available online: https://www.statology.org/bartletts-test-of-sphericity/#:~:text=Bartlett's%20Test%20of%20Sphericity%20compares,are%20orthogonal%2C%20i.e.%20not%20correlated (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. Interpretation and application of factor analytic results. In A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Building resilience to promote sustainability. IHDP Update 2003, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

| χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|

| 1061 | 190 | <0.001 |

| Items | MSA |

|---|---|

| Overall | 0.903 |

| Size of the SHG plays an important role | 0.835 |

| Economically weaker members make group work easy | 0.914 |

| Meeting every week | 0.906 |

| The attendance rate per meeting should be high | 0.922 |

| All members should participate in decision-making | 0.905 |

| All members should equally share responsibility | 0.895 |

| Rules and regulations are important for the group | 0.933 |

| Savings is important | 0.935 |

| Easy access to loans is good for the group | 0.856 |

| All members must participate in loan repayment | 0.903 |

| Rotation of the common fund is required | 0.875 |

| Idle capital is not good for the group | 0.940 |

| Cash handling can be done by any member | 0.883 |

| Resource mobilization in one place is good for the group | 0.916 |

| Bookkeeping and financial documentation are important | 0.947 |

| Auditing is important | 0.908 |

| Training programs are critical for group functioning | 0.895 |

| Planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the program by group members is important | 0.913 |

| Participation in community programs is essential for group functioning | 0.886 |

| Literacy is important for the group | 0.858 |

| Component | Eigenvalue | % of Variance | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.165 | 35.83 | 35.8 |

| 2 | 1.362 | 6.81 | 42.6 |

| 3 | 1.144 | 5.72 | 48.4 |

| 4 | 1.082 | 5.41 | 53.8 |

| 5 | 0.895 | 4.48 | 58.2 |

| 6 | 0.879 | 4.39 | 62.6 |

| 7 | 0.811 | 4.05 | 66.7 |

| 8 | 0.761 | 3.80 | 70.5 |

| 9 | 0.725 | 3.62 | 74.1 |

| 10 | 0.701 | 3.50 | 77.6 |

| 11 | 0.615 | 3.08 | 80.7 |

| 12 | 0.573 | 2.86 | 83.6 |

| 13 | 0.563 | 2.82 | 86.4 |

| 14 | 0.493 | 2.47 | 88.8 |

| 15 | 0.457 | 2.28 | 91.1 |

| 16 | 0.435 | 2.18 | 93.3 |

| 17 | 0.373 | 1.86 | 95.2 |

| 18 | 0.352 | 1.76 | 96.9 |

| 19 | 0.327 | 1.63 | 98.6 |

| 20 | 0.289 | 1.45 | 100.0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 3 | - | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | - | |||

| Components | Uniqueness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Auditing is important | 0.684 | 0.443 | |||

| Resource mobilization in one place is good for the group | 0.675 | 0.431 | |||

| Training programs are critical for group functioning | 0.673 | 0.427 | |||

| Planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the program by group members is important | 0.627 | 0.471 | |||

| All members must participate in loan repayment | 0.530 | ||||

| The attendance rate per meeting should be high | 0.503 | ||||

| Cash handling can be done by any member | 0.713 | 0.399 | |||

| All members should participate in decision-making | 0.648 | 0.424 | |||

| Rules and regulations are important for the group | 0.419 | ||||

| Meeting every week | 0.437 | ||||

| Bookkeeping and financial documentation are important | 0.523 | ||||

| All members should equally share responsibility | 0.602 | ||||

| Savings is important | 0.589 | ||||

| Size of the SHG plays an important role | 0.706 | 0.359 | |||

| Rotation of the common fund is required | 0.602 | 0.439 | |||

| Idle capital is not good for the group | 0.518 | ||||

| Economically weaker members make group work easy | 0.591 | ||||

| Literacy is important for the group | 0.713 | 0.387 | |||

| Participation in community programs is essential for group functioning | 0.666 | 0.443 | |||

| Easy access to loans is good for the group | 0.601 | 0.314 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghosh, S.; Ray, S.; Nair, R. Sustainability Factors of Self-Help Groups in Disaster-Affected Communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010647

Ghosh S, Ray S, Nair R. Sustainability Factors of Self-Help Groups in Disaster-Affected Communities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010647

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhosh, Sameek, Sougata Ray, and Rajiv Nair. 2023. "Sustainability Factors of Self-Help Groups in Disaster-Affected Communities" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010647

APA StyleGhosh, S., Ray, S., & Nair, R. (2023). Sustainability Factors of Self-Help Groups in Disaster-Affected Communities. Sustainability, 15(1), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010647