Gamification of Culture: A Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Local Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Entangling Streams of Culture, Creativity, Economy, and Industries

2.1. Sustainability for Peripheral Areas via Cultural Innovation

2.2. Gamification of Culture

2.3. Opportunity for Tangible Gamified Cultural Products in the Emerging Orange Economy

3. Gamification Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Local Sustainable Development

3.1. Principles of the “Gamification of Culture”

- 1.

- Aesthetic: Cultural experience is the core of cultural innovation. Therefore, when extracting cultural content, designers should have a clear goal of what to preserve.

- 2.

- Mechanism: A fundamental belief is that a game mechanism is a simplified extraction of the real world when being developed for culture preservation. Therefore, instead of developing a game mechanism from scratch, designers should search for a mechanism that channels user behaviors toward the selected cultural content.

- 3.

- Dynamic: Designers must be careful with the game dynamics when finetuning the game, and the gameplay must be smooth and fun.

3.2. Cultural Content as Design Material

3.2.1. Food

3.2.2. Clothing

3.2.3. Habitation

3.2.4. Marriage

3.2.5. Music and Literature: Tanka Ballads

4. Culture Game Development: The Tanka Ballad Game

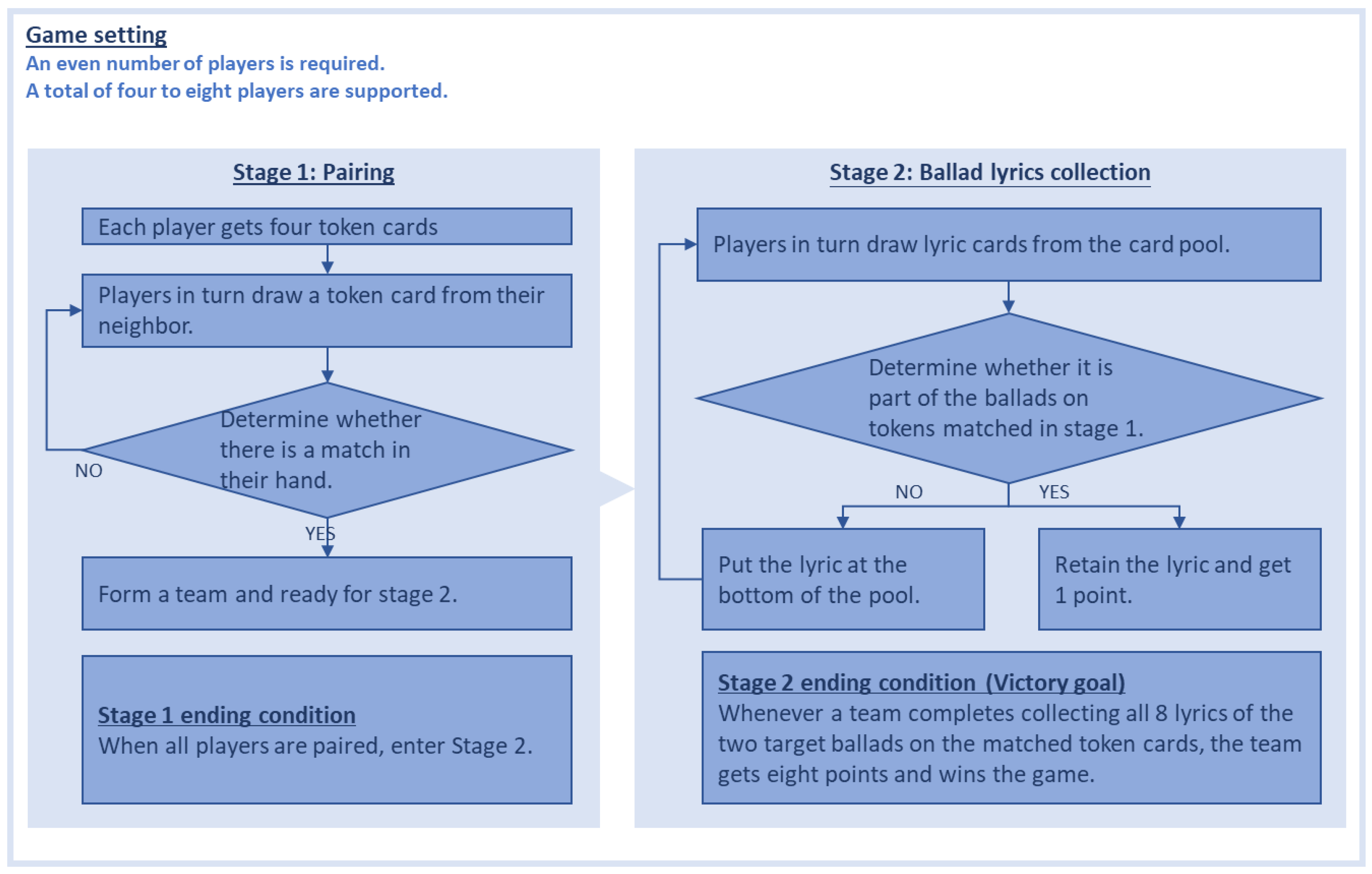

4.1. Game Structure and Victory Goal

4.2. Mechanisms and Rules

- 1.

- At the beginning of the game, each player is dealt four token cards.

- 2.

- A starting player may draw a card from their neighbor. If the player picks a card with the same token as another card in their hand, the matching pair can be claimed, and the two players form a team. The rest of the cards in their hand go to the discarded pile. The drawing of cards continues in turn until all players have found a match. For example, if Player 1 draws a card from Player 2 and picks a token card that is the same as a card in Player 1’s hand, Player 1 can claim the matching pair and form a team with Player 2; if there is no match, it is Player 2’s turn to draw a card from their neighbor, and the game goes on like this.

- 3.

- When all players are paired up, the game goes on to the next stage.

- 1.

- The first paired team is the first to draw lyric cards, as they were ahead in the matching process. The rest of the teams draw according to the sequence of success in pairing or determined jointly by all players.

- 2.

- During the card drawing, when a player picks one lyric that belongs to the target ballads, the player receives one point; if they do not pick a target lyric, nothing happens, and the lyric goes to the bottom of the pool. In maintaining balance in the game, each player can have no more than seven cards in their hand, and any extra ones are discarded.

- 3.

- The pool also contains event cards that introduce related marriage customs, providing players with events or actions that the player must carry out immediately or in the following rounds as prescribed on the cards.

- 4.

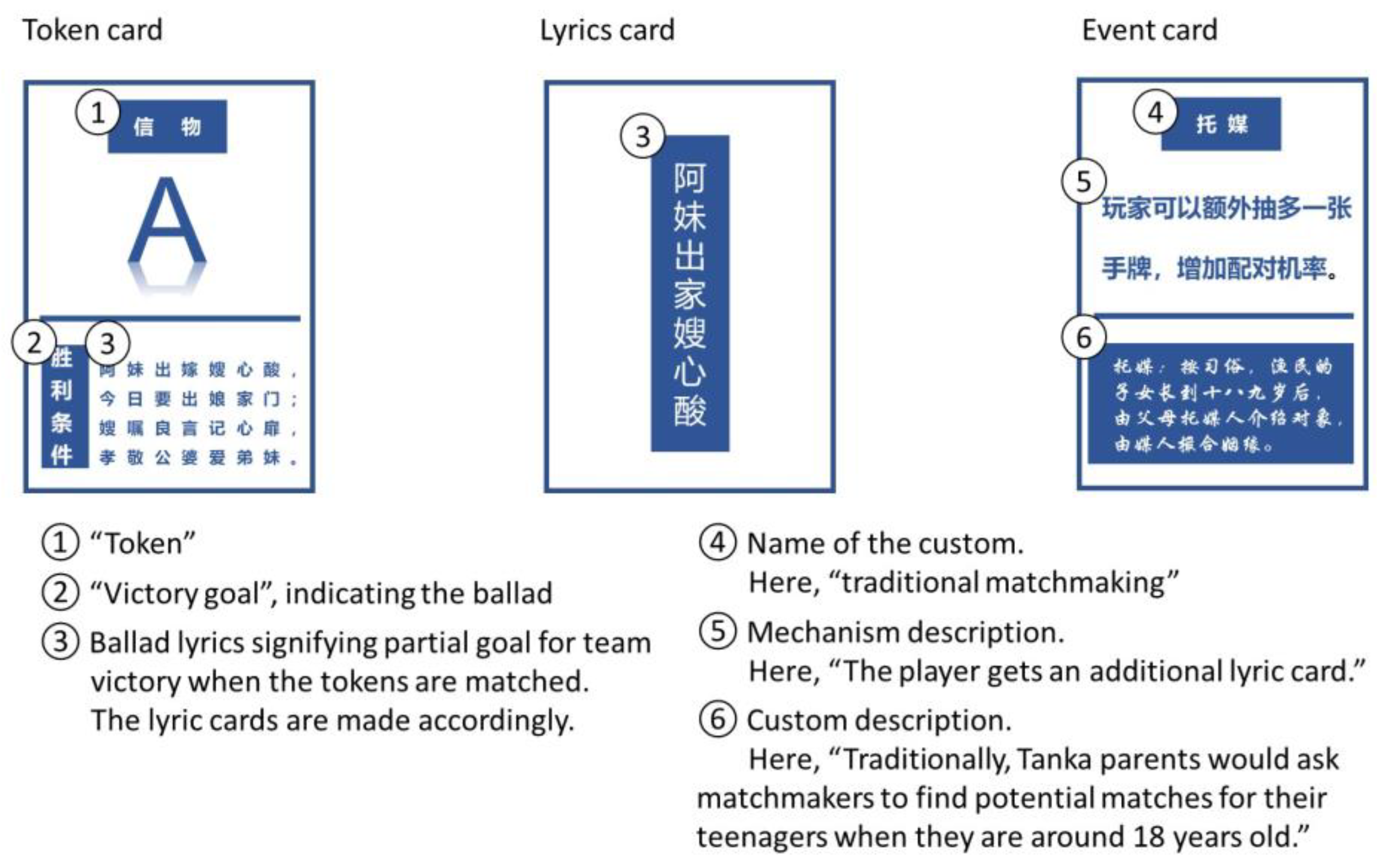

- When a team collects all eight lyrics of the two target ballads on the matched token cards, the team receives eight points and wins the game. The formats for token cards, lyric cards, and event cards can be seen in Figure 6.

4.3. Demonstration of the Tangible Gamified Cultural Product

5. Discussions

5.1. Value of Tangible Culture Product for Peripheral Areas

5.2. Gamification Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Sustainability in Peripheral Areas

- 1.

- Cultural experience is arguably the primary target of preservation. It is also at the core of cultural innovation and provides the aesthetic for the game to be developed. Therefore, when extracting cultural content at the very beginning of a project, designers need to achieve consensus with local stakeholders on what to preserve.

- 2.

- In the same vein, instead of introducing novel forms of interaction, designers should search for interaction that channels user behaviors to resemble the selected cultural content. More specifically, systematic mapping between mechanisms and cultural content is still lacking. Thus, deciding on a game mechanism is reliant largely on the designer’s experience. Other tactics include incorporating game designers/experts or turning to collections, such as boardgamegeek.com, for inspiration.

- 3.

- In terms of game dynamics, the “gamification of culture” actually has a similar dilemma to games for learning, which is balancing the need to cover the subject matter with the desire to prioritize gameplay [99]. As cultural innovation must first be self-sustaining, it is strongly suggested that the game must at least be smooth and fun.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heal, G. Reflections—Defining and Measuring Sustainability. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2012, 6, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedmann, J. Urbanization, Planning, and National Development; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Imperiale, F.; Fasiello, R.; Adamo, S. Sustainability Determinants of Cultural and Creative Industries in Peripheral Areas. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikienė, D.; Kačerauskas, T. The creative economy and sustainable development: The Baltic States. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.M.; Graves, D. Tangible Benefits From Intangible Resources: Using Social and Cultural History to Plan Neighborhood Futures. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-Sustainability Relation: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Committee for Promotion of Ming-Qing Studies of Academia Sinica. Lecture Notes of “Tanka by Pearl River—Ethnicity from an Historical Perspective” by Prof. Liu Zhiwei. Available online: http://mingching.sinica.edu.tw/Academic_Detail/232 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Greffe, X. From culture to creativity and the creative economy: A new agenda for cultural economics. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. Cultural economy: Achievements, divergences, future prospects. Geogr. Res. 2012, 50, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Kong, L. Cultural economy: A critical review. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayne, M.; Gibson, C.; Waitt, G.; Bell, D. The cultural economy of small cities. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y. The Role of Cultural Creative Industries on the Revitalization of Resource-exhausted Cities–The Case of Tongling. J. Urban Cult. Res. 2021, 23, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, E.; O’brien, D. Sociology, sociology and the cultural and creative industries. Sociology 2020, 54, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, R.L.; Liu, J.S.; Ho, M.H.-C. What are the concerns? Looking back on 15 years of research in cultural and creative industries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2018, 24, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, A.; Segre, G. Culture and human capital in a two-sector endogenous growth model. Res. Econ. 2011, 65, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, Q. Cultural and creative industries and urban (re) development In China. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. The concentric circles model of the cultural industries. Cult. Trends 2008, 17, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, A.; Sacco, P.L.; Segre, G. Smart endogenous growth: Cultural capital and the creative use of skills. Int. J. Manpow. 2014, 35, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G. From culture 1.0 to culture 3.0: Three socio-technical regimes of social and economic value creation through culture, and their impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class. City Community 2003, 2, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.A.; Fritsch, M. Creative class and regional growth: Empirical evidence from seven European countries. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 391–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batabyal, A.A.; Yoo, S.J. Schumpeterian creative class competition, innovation policy, and regional economic growth. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2018, 55, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donegan, M.; Drucker, J.; Goldstein, H.; Lowe, N.; Malizia, E. Which indicators explain metropolitan economic performance best? Traditional or creative class. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, P.; Murphy, E.; Redmond, D. Residential preferences of the ‘creative class’? Cities 2013, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, Y.F. Exploring creative class mobility: Hong Kong creative workers in Shanghai and Beijing. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2017, 58, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harney, S. Creative industries debate. Cult. Stud. 2010, 24, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, F.H. Measuring and managing creative labour: Value struggles and billable hours in the creative industries. Organization 2020, 29, 1350508420968187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, J. Creative labour, cultural work and individualisation. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2010, 16, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F.; Innocenti, N. The rise of cultural and creative industries in creative economy research: A bibliometric analysis. In Creative Industries and Entrepreneurship; Lazzeretti, L., Vecco, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, K. Not So Cool Britannia:The Role of the Creative Industries in Economic Development. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2004, 7, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontje, M.; Musterd, S. Creative industries, creative class and competitiveness: Expert opinions critically appraised. Geoforum 2009, 40, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Działek, J. Cultural heritage in building and enhancing social capital. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.H.; Koster, R.; Youroukos, N. Tangible and intangible indicators of successful aboriginal tourism initiatives: A case study of two successful aboriginal tourism lodges in Northern Canada. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. Cultural tourism as serious leisure. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Yoon, Y.-S. Developing sustainable rural tourism evaluation indicators. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete-Sáez, C.A.; Mar Fuentes-Fuentes, M.; Javier Lloréns-Montes, F. Service quality measurement in rural accommodation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachleitner, R.; Zins, A.H. Cultural Tourism in Rural Communities: The Residents’ Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Østervig Larsen, M. Innovation gaps in Scandinavian rural tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Lo, M.-C. Rural tourism quality of services: Fundamental contributive factors from tourists’ perceptions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moscardo, G. Peripheral Tourism Development: Challenges, Issues and Success Factors. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianioglo, A.; Rissanen, M. Global trends and tourism development in peripheral areas. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 20, 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.P.; Ramos, R.A.R. Heritage Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development Strategies and Constraints. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J. Exploration of local culture elements and design of cultural creativity products. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2010, 13, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.; Shieh, M.-D. A study of the cultural and creative product design of phalaenopsis in Taiwan. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2018, 21, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.-T. Transforming Taiwan aboriginal cultural features into modern product design: A case study of a cross-cultural product design model. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J. Toys and communication: An introduction. In Toys and Communication; Magalhães, L., Goldstein, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.; Macedo, J. Learning sustainable development with a new simulation game. Simul. Gaming 2000, 31, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuntjara, A.P. Art toy as a tool for engaging the global public on the city of Surabaya. Creat. Ind. J. 2022, 15, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.; Cohen, E. Sociology and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palys, T.S. Simulation methods and social psychology. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1978, 8, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Villalba, M.J.; Leiva Olivencia, J.J.; Navas-Parejo, M.R.; Benítez-Márquez, M.D. Higher education students’ assessments towards gamification and sustainability: A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K. Children and advergames: The role of product involvement, prior brand attitude, persuasion knowledge and game attitude in purchase intentions and changing attitudes. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 520–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining” gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Morford, Z.H.; Witts, B.N.; Killingsworth, K.J.; Alavosius, M.P.J.T.B.A. Gamification: The intersection between behavior analysis and game design technologies. Behav. Anal. 2014, 37, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J.J.E.M. A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunha, C.R.; Mendonça, V.; Morais, E.P.; Carvalho, A. The role of gamification in material and immaterial cultural heritage. In Proceedings of 31st International Business Information Management Association Conference (IBIMA), Milan, Italy, 25–26 April 2018; pp. 6121–6129. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacini, E.; Giaccone, S.C. Gamification and cultural institutions in cultural heritage promotion: A successful example from Italy. Cult. Trends 2022, 31, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-R.; Wang, Y.-C.; Huang, W.-S.; Tang, W.-C. Festival gamification: Conceptualization and scale development. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J. Gamification and the festival experience: The case of Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M. New technologies and cultural consumption—Edutainment is born! Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenros, J. The game definition game: A review. Games Cult. 2017, 12, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suits, B. Games and their institutions in The Grasshopper. J. Philos. Sport 2006, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwengerer, L. An Epistemic Condition for Playing a Game. Sport Ethics Philos. 2019, 13, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, A.J. Game-Playing Without Rule-Following. J. Philos. Sport 2011, 38, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suits, B. What is a Game? Philos. Sci. 1967, 34, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suits, B. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luzardo, A.; Gasca, L. Launching an Orange Future: Fifteen Questions for Getting to Know the Creative Entrepreneurs of Latin America and the Caribbean. 2018. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/en/launching-orange-future-fifteen-questions-getting-know-creative-entrepreneurs-latin-america-and (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Sandri, S.; Alshyab, N. Orange Economy: Definition and measurement—The case of Jordan. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria Roa, L.A.; Castillo, H.G.; Montiel Ariza, H. Orange economy: Study on the behavior of cultural and creative industries in Colombia. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro-Seoane, F.J.; Llorca-Ponce, A.; Rius-Sorolla, G. Measuring the Sustainability of the Orange Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.P.; Granados, R.H.; Andrade, S.L.C. Answers to the Crisis in the Tourism Sector in a COVID Environment: The Orange Economy Cluster Initiative in the State of Boyacá, Colombia. In Handbook of Research on Cultural Tourism and Sustainability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 253–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. Game mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics. Libr. Technol. Rep. 2015, 51, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hunicke, R.; LeBlanc, M.; Zubek, R. MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. In AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2004; p. 1722. [Google Scholar]

- Walk, W.; Görlich, D.; Barrett, M. Design, dynamics, experience (DDE): An advancement of the MDA framework for game design. In Game Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D. Encyclopedia of Law & Society: American and Global Perspectives; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, T. The idea of cultural patrimony. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 1998, 1, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados-Peña, M.B.; Gutiérrez-Carrillo, M.L.; Del Barrio-García, S. The development of loyalty to earthen defensive heritage as a key factor in sustainable preventive conservation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swartzburg, S.G. Preservation of the cultural patrimony. Art Libr. J. 1990, 15, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, C. Cultural Heritage. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition); Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, K.G. Chapter 7—The Use of Stated Preference Methods to Value Cultural Heritage. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture; Ginsburgh, V.A., Throsby, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 145–181. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, R. Cultural Heritage, Patrimony, and Repatriation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J. Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue: UNESCO World Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McFadzean, A.J.S.; Todd, D. Cooley’s anaemia among the tanka of South China. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971, 65, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woon, Y.-f. Social Organization in South China, 1911-1949: The Case of the Kuan Lineage of Kʻai-pʻing County; University of Michigan Center for Chinese: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, R.B. Boat People, Land People: Approach to the Social Organization of Cultural Differences in South China. Rev. De Cult. 1987, 2, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Hu, M. ‘Sea Gypsies’ Find Their Feet and Prosper. 30 October 2019. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/global/2019-10/30/content_37519416.htm (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Shi, Y. ‘Water Gypsies’ Fear Lifestyle Sea Change. 2011. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/2011-02/24/content_12068512.htm (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Buckley, C.; Wu, A. In China, an Ancient People Watch Their Floating Life Dissolve. The New York Times. 2017. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/23/world/asia/china-tanka-river-people-datang.html (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Timmy, C.C.-T. Ballad on the Shore (岸上漁歌). 2017. Directed by Ma Chi-hang. Produced by May Fung and Eno Yim. In Cantonese and Tanka with Chinese and English subtitles. 98 minutes. Colour, DVD forthcoming. Distributed by ACO ([email protected]). Yearb. Tradit. Music 2019, 51, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. COVID-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Sie, L.; Faturay, F.; Auwalin, I.; Wang, J. Who are vulnerable in a tourism crisis? A tourism employment vulnerability analysis for the COVID-19 management. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chiu, C.L.; Mo, S.; Marjerison, R. The nature of crowdfunding in China: Initial evidence. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMarshedi, A.; Wanick, V.; Wills, G.B.; Ranchhod, A. Gamification and behaviour. In Gamification; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Santos, C.; Pimentel, P.; Sousa, Á.; Faria, S.; Batista, M.d.G. Guidelines for Tourism Sustainability in Ultra-Peripheral Territories: A Research Based on the Azores Region’s Touristic Companies’ Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, J.L.; Homer, B.D.; Kinzer, C.K. Foundations of game-based learning. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasio, A.; Madge, O.-L.; Harviainen, J.T. Games, Gamification and Libraries. In New Trends and Challenges in Information Science and Information Seeking Behaviour; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, N.i.S. Individual Cognitive Structuring and the Sociocultural Context: Strategy Shifts in the Game of Dominoes. J. Learn. Sci. 2005, 14, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Guangdong Province 1 | Growth Rate (%) | Dongguan City 2 | Growth Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 397,183,900 | - | 37,919,755 | - |

| 2017 | 443,475,600 | 11.65% | 41,418,524 | 9.23% |

| 2018 | 488,078,293 | 10.60% | 44,338,730 | 7.05% |

| 2019 | 531,410,169 | 8.41% | 47,486,106 | 7.10% |

| Year | 1-Star or Above Hotels | 4-Star Hotels | 5-Star Hotels | Total Beds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 29 | 11 | 13 | 13,360 |

| 2020 | 26 | 10 | 12 | 12,078 |

| 2021 | 22 | 7 | 11 | 9096 |

| Year | Domestic (Growth Rate) | International (Growth Rate) | Total Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 43,436,255 (7.73%) | 4,049,851 (0.76%) | 5,741,640 (8.46%) |

| 2020 | 38,517,004 (−24.86%) | 248,269 (−80.29%) | 3,586,295 (−30.17%) 2 |

| 2021 | 45,306,822 (17.63%) | 228,784 (−7.85%) | 3,795,765 (5.84%) 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, C.-H.; Chao, Y.-L.; Xiong, J.-T.; Luh, D.-B. Gamification of Culture: A Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Local Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010650

Wu C-H, Chao Y-L, Xiong J-T, Luh D-B. Gamification of Culture: A Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Local Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010650

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chi-Hua, Yu-Lin Chao, Jia-Ting Xiong, and Ding-Bang Luh. 2023. "Gamification of Culture: A Strategy for Cultural Preservation and Local Sustainable Development" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010650