Causes and Behavioral Evolution of Negative Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: Considering the Mediating Role of User Involvement and the Moderating Role of User Self-Construal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

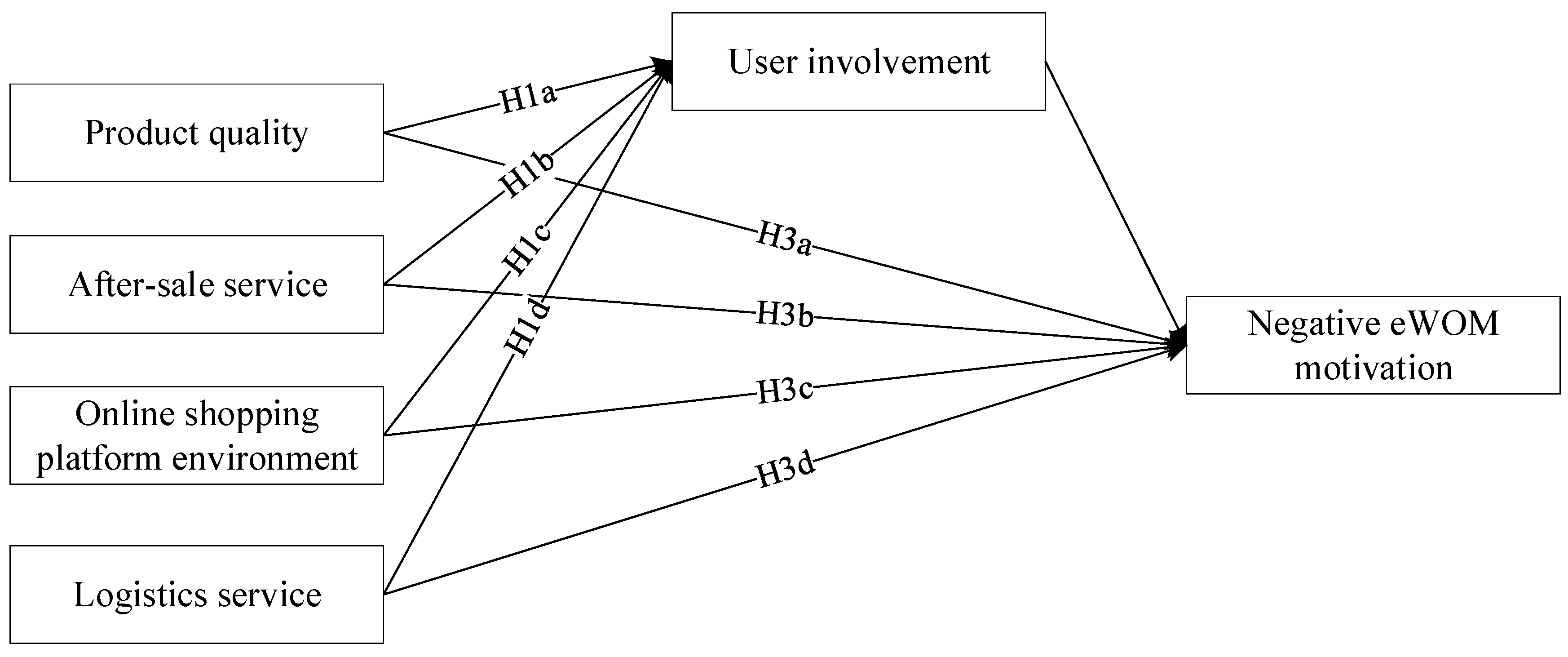

2.1. Negative Online Shopping Experience and User Involvement

2.2. The Mediating Role of User Involvement

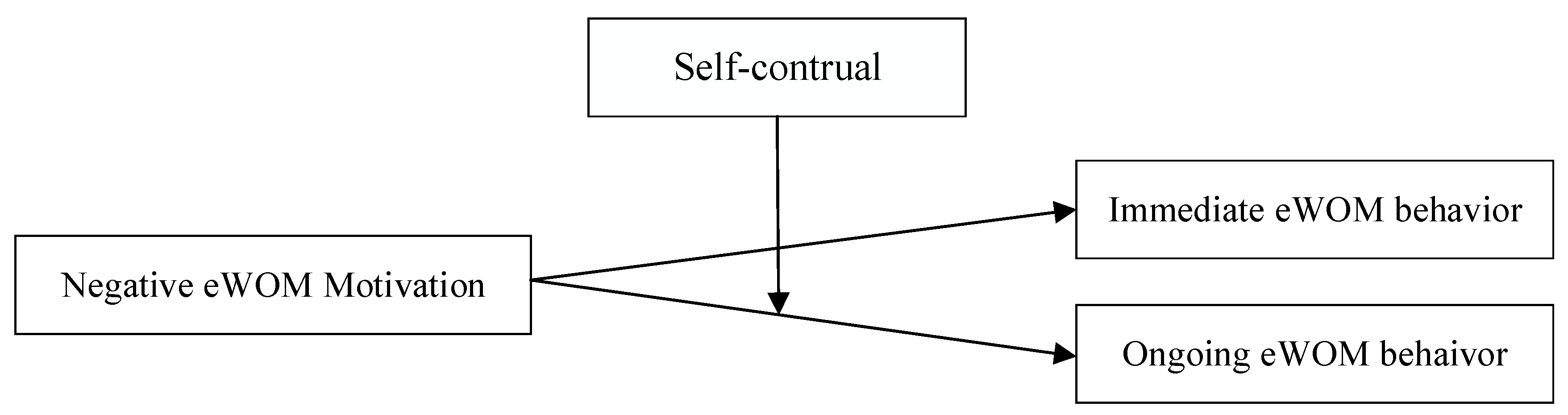

2.3. Negative eWOM Motivations and Behavior

2.4. The Moderating Role of User Self-Construal

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures and Questionnaire

3.2. Reliability and Validity

4. Results

4.1. Structural Model 1

4.2. Mediation Effects

4.3. Structural Model 2

4.4. Moderation Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

- The results of the empirical analysis showed that negative product quality, negative platform environment, negative logistics and negative after-sales service all had different degrees of influence on the motivation of negative eWOM communication. There is a significant positive correlation between negative product quality and negative platform environment and user involvement.

- User involvement was positively associated with negative eWOM communication motivations and was partially mediated between negative product quality, negative online shopping platform environment and negative eWOM motivation.

- There was a significant positive correlation between negative eWOM motivation and the two kinds of eWOM communication behaviors.

- Under immediate eWOM behavior, the user’s self-construal moderated the relationship between eWOM motivation and immediate eWOM behavior, while this moderating effect is not significant under ongoing eWOM behavior.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Gender | a. Male b. Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | a. <20 | b. 21–30 | c. 31–40 | d. 41–50 | |

| Education | a. High school | b. College | c. Undergraduate | d. Master | e. Doctor |

| Online shopping experience (years) | a. Less than 1 y | b. 1–2 y | c. 3–5 y | d. 6–10 y | e. More than 10 y |

| Career | a. Student | b. Teacher | c. Civil Servant | d. Company employee | e. Self-employed |

| Monthly Revenue (RMB) | a. 0–3000 | b. 3001–6000 | c. 6001–10,000 | d. 10,000–15,000 | e. >15,000 |

| Items for Negative Product Quality | Inconformity ←--------→ Conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The actual product received is not the same as the product shown in the picture on the page. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. Merchants resell defective products that have been returned or exchanged. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. The date of manufacture of products purchased online (especially food) is not fresh (expired). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for After-sales service quality | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. Human customer service cannot respond to after-sales inquiries in a timely manner or shows impatience in their attitude. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. The merchant’s process for handling returns and exchanges is cumbersome and the review speed for refunds is slow. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. In the event of a price reduction within the price guarantee period, the merchant is willing to compensate the difference in price for the consumer who has purchased the product. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for Online shopping platform environments | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. The information on the product detail page is incomplete and the advertising content is exaggerated. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. The rules of online shopping coupons, allowances, reductions and other promotional activities are complicated, and the prompt of not meeting the conditions of the offer often occurs when paying | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Merchants often raise prices before discounting, misleading consumers with false discounts. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for Logistics service quality | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. In order to save costs, sellers choose low-cost logistics, rather than high-quality logistics like “SF”. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. There is a “false shipment” where the merchant has confirmed the shipment but there is a delay in the collection information. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. When the logistics information is not updated for a long time, the seller cannot help communicate with the logistics in time. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for User involvement | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. I will carefully compare the intended products across platforms and will not place an order until I have selected the most cost-effective product. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. I will vigorously defend my rights even if it takes a lot of time and effort. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. If the merchant’s service remedies do not satisfy me, I will further complain through other channels. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for Negative eWOM motivation | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. I want to vent my frustration by posting negative comments. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. I want to show my professionalism and gain the approval of other users by posting negative reviews. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. I want to get amusement by posting negative reviews. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. I hope to punish the merchant by posting negative reviews to warn other consumers not to buy this product. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. I want to get advice and help from other users by posting negative reviews. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for Self-construal | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. I am able to be consistent with anyone. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. I am curious and willing to try new things. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. I would rather reject someone outright than be misunderstood. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. In small groups, I often play the “leader” role. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. Speaking in public is no problem for me. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. If I disagree with my colleagues, I will give in to avoid arguments. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. My parents’ opinions have a great influence on me when it comes to life events such as studying and choosing a career. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. For the good of the group, I would rather sacrifice my own interests. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. I prefer people who are modest and prudent. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. When my family and friends around me feel happy, I feel happy too. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Items for Negative eWOM behavior | Inconformity←--------→conformity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 1. Once an unpleasant shopping experience occurs, I will publish a bad review on the platform as soon as possible. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. When I have an unpleasant shopping experience, I may tell people around me through social media such as wechat. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Once an unpleasant shopping experience occurs, I will quickly apply to the user service (administrator) of the online shopping platform for intervention. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. Long after I had a bad shopping experience, I would leave comments on information sharing sites describing my bad shopping experience. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. I would repeatedly post and reply to negative posts I had posted in order to get more attention. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. I will write a post about my impressive negative online shopping experience on social platforms such as Douban, Little Red Book. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

References

- Arndt, J. Role of Product-Related Conversations in the Diffusion of a New Product. J. Mark. Res. 1967, 4, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Broderick, A.J.; Lee, N. Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.; Hernández-Maestro, R.M.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A. Marketing decisions, user reviews, and business performance: The use of the Toprural website by Spanish rural lodging establishments. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda Filho, E.J.M.; Barcelos, A.D.A. Negative online word-of-mouth: Consumers’ retaliation in the digital world. J. Glob. Mark. 2021, 34, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Monzoncillo, J.M.; de Haro Rodríguez, G.; Picard, R.G. Digital word of mouth usage in the movie consumption decision process: The role of Mobile-WOM among young adults in Spain. Int. J. Media Manag. 2018, 20, s107–s128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Sangeetha, R. How Does Electronic Word of Mouth Impact Green Hotel Booking Intention? Serv. Mark. Q. 2022, 43, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.S. Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yan, Q.; Yan, M.; Shen, C. Tourists’ emotional changes and eWOM behavior on social media and integrated tourism websites. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, B.; Lee, M.S. A causal model of consumer involvement. J. Econ. Psychol. 1989, 10, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.G.; Andrews, J.C. Adherence of prime-time televised advertising disclosures to the “clear and conspicuous” standard: 1990 versus 2002. J. Public Policy Mark. 2004, 23, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Lin, B. Do electronic word-of-mouth and elaboration likelihood model influence hotel booking? J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2019, 59, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O. Ambivalence and involvement in the satisfaction-repurchase loyalty relationship. Australas. Mark. J. 2010, 18, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.A.; Awang, Z.; Nasir, J.; Sabiu, I.T.; Usop, R.; Muhamad, S.F. Antecedents and Outcome of Electronic Word of Mouth (EWOM): Moderating Role of Product Involvement. J. Manag. Oper. Res. 2019, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Compound attitudes, user engagement and eWOM: An empirical study on WeChat. In Proceedings of the CONF-IRM 2015, Songdo, Republic of Korea, 24–26 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L. The antecedents of user satisfaction and its link to complaint intentions in online shopping: An integration of justice, technology, and trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Osburg, V.S.; Yoganathan, V.; Cartwright, S. Social sharing of consumption emotion in electronic word of mouth (eWOM): A cross-media perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoner-Schatz, L.; Hofmann, V.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Destination’s social media communication and emotions: An investigation of visit intentions, word-of-mouth and travelers’ facially expressed emotions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 22, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. Beyond valence in user dissatisfaction: A review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.S.; Mitra, K.; Webster, C. Word of-Mouth Communications: A Motivational Analysis. Adv. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzer, I.M.; Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. “Never eat in that restaurant, I did!” Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 24, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.L.; Householder, B.J.; Greene, K.L. The theory of reasoned action. In The SAGE Handbook of Persuasion: Developments in Theory and Practice; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 14, pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Kim, H.J. Positive and negative eWOM motivations and hotel customers’ eWOM behavior: Does personality matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calancie, O.; Ewing, L.; Narducci, L.D.; Horgan, S.; Khalid-Khan, S. Exploring how social networking sites impact youth with anxiety: A qualitative study of Facebook stressors among adolescents with an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komunda, M.; Osarenkhoe, A. Remedy or cure for service failure? Effects of service recovery on customer satisfaction and loyalty. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2012, 18, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, J.; Schwartz, E.M. What drives immediate and ongoing word of mouth? J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Scammon, D.L. Does feeling holier than others predict good deeds? Self-construal, self-enhancement and helping behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, V.; Schwayer, L.M.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E.; Wanisch, A.T. Consumers’ self-construal: Measurement and relevance for social media communication success. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 959–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.L.; Song, M.M.; Duan, Y.C.; Hong, Y.; Sui, W.J. The Influence of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Dispersion on Order Decision from the Perspective of Self-Construal. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1994, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baaren, R.B.; Ruivenkamp, M. Self-construal and values expressed in advertising. Soc. Influ. 2007, 2, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; van Rijn, M.B.; Sanders, K. Perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing: Employees’ self-construal matters. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 2217–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli-Salehi, R.; Torres, I.M.; Madadi, R.; Zúñiga, M.Á. The Role of Self-Construal and Competitiveness in Consumers’ Self-Brand Connection with Domestic vs. Foreign Brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qian, C.; He, M.T. A study of location-based online comment information sharing behavior in virtual communities. Intell. Sci. 2018, 36, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, T.M.; Prabhakar, G.; Ilavarasan, P.V.; Baabdullah, A.M. Up the ante: Electronic word of mouth and its effects on firm reputation and performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Thadani, D.R. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Wilson, A. Shopping in the digital world: Examining customer engagement through augmented reality mobile applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, R.; Li, D.; Fan, H. Can scarcity of products promote or restrain consumers’ word-of-mouth in social networks? The moderating roles of products’ social visibility and consumers’ self-construal. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Law, R.; Duan, Y. What are the obstacles in the way to “avoid landmines”? Influence of electronic word-of-mouth dispersion on order decision from the self-construal perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Lien, C.H.; Cao, Y. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on WeChat: Examining the influence of sense of belonging, need for self-enhancement, and consumer engagement on Chinese travellers’ eWOM. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhidari, A.; Iyer, P.; Paswan, A. Personal level antecedents of eWOM and purchase intention, on social networking sites. J. Cust. Behav. 2015, 14, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 173 | 54.40% |

| Female | 145 | 45.60% | |

| Age | ≤20 | 35 | 11.01% |

| 21–30 | 120 | 37.74% | |

| 31–40 | 58 | 18.24% | |

| 41–50 | 64 | 20.13% | |

| ≥51 | 41 | 12.89% | |

| Education | High school | 57 | 17.92% |

| College | 136 | 42.77% | |

| Undergraduate | 100 | 31.45% | |

| Master | 14 | 4.40% | |

| Doctor | 11 | 3.46% | |

| Age of online shopping | ≤1 y | 12 | 3.77% |

| 1–2 y | 59 | 18.55% | |

| 3–5 y | 164 | 51.57% | |

| 5–10 y | 71 | 22.33% | |

| ≥10y | 12 | 3.77% | |

| Job | Student | 38 | 11.95% |

| Teacher | 39 | 12.26% | |

| Civil Servant | 32 | 10.06% | |

| Self-employed | 130 | 40.88% | |

| Employees | 68 | 21.38% | |

| Jobless/freelance | 11 | 3.46% | |

| Monthly revenue | 0–3000 | 47 | 14.78% |

| 3000–6000 | 141 | 44.34% | |

| 6000–1000 | 97 | 30.50% | |

| 10,000–15,000 | 21 | 6.60% | |

| ≥15,000 | 12 | 3.77% |

| CITC | α | CR | AVE | Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Quality (A) | A1 | 0.759 | 0.887 | 0.857 | 0.666 | 0.791 |

| A2 | 0.863 | 0.852 | ||||

| A3 | 0.721 | 0.804 | ||||

| After-sales Service (B) | B1 | 0.780 | 0.920 | 0.912 | 0.777 | 0.803 |

| B2 | 0.885 | 0.967 | ||||

| B3 | 0.849 | 0.867 | ||||

| Platform Environment (C) | C1 | 0.770 | 0.896 | 0.872 | 0.696 | 0.774 |

| C2 | 0.870 | 0.914 | ||||

| C3 | 0.746 | 0.810 | ||||

| Logistics Service (D) | D1 | 0.741 | 0.890 | 0.844 | 0.643 | 0.802 |

| D2 | 0.871 | 0.794 | ||||

| D3 | 0.748 | 0.811 | ||||

| User Involvement (E) | J1 | 0.728 | 0.887 | 0.820 | 0.603 | 0.786 |

| J2 | 0.869 | 0.724 | ||||

| J3 | 0.745 | 0.817 | ||||

| Negative eWOM Motivation (F) | F1 | 0.797 | 0.935 | 0.916 | 0.686 | 0.863 |

| F2 | 0.817 | 0.817 | ||||

| F3 | 0.832 | 0.724 | ||||

| F4 | 0.850 | 0.813 | ||||

| F5 | 0.835 | 0.913 | ||||

| Self-construal type (G) | G1 | 0.863 | 0.967 | 0.966 | 0.740 | 0.856 |

| G2 | 0.856 | 0.846 | ||||

| G3 | 0.829 | 0.820 | ||||

| G4 | 0.816 | 0.826 | ||||

| G5 | 0.891 | 0.901 | ||||

| G6 | 0.842 | 0.886 | ||||

| G7 | 0.867 | 0.890 | ||||

| G8 | 0.806 | 0.811 | ||||

| G9 | 0.832 | 0.857 | ||||

| G10 | 0.893 | 0.903 | ||||

| Negative eWOM behavior (H) | H1 | 0.849 | 0.949 | 0.919 | 0.655 | 0.791 |

| H2 | 0.859 | 0.857 | ||||

| H3 | 0.841 | 0.783 | ||||

| H4 | 0.822 | 0.821 | ||||

| H5 | 0.895 | 0.803 | ||||

| H6 | 0.802 | 0.799 |

| Mean | SD | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4.797 | 1.401 | 0.863 | |||||||

| B | 4.760 | 1.363 | 0.353 | 0.881 | ||||||

| C | 4.787 | 1.389 | 0.256 | 0.245 | 0.861 | |||||

| D | 4.867 | 1.424 | 0.347 | 0.452 | 0.309 | 0.861 | ||||

| E | 4.820 | 1.457 | 0.492 | 0.338 | 0.367 | 0.301 | 0.871 | |||

| F | 4.950 | 1.434 | 0.375 | 0.420 | 0.474 | 0.443 | 0.301 | 0.876 | ||

| G | 4.941 | 1.377 | 0.202 | 0.267 | 0.234 | 0.323 | 0.421 | 0.118 | 0.860 | |

| H | 4.997 | 1.350 | 0.221 | 0.397 | 0.331 | 0.142 | 0.311 | 0.224 | 0.306 | 0.809 |

| Test Statistic | RMR | RMSEA | GFI | RFI | CFI | PGFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.97 | 0.874 | 0.908 | 0.547 | 0.885 |

| Hypotheses and Paths | Load Factor | Standard Error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: User involvement ← Negative product quality | 0.401 | 0.055 | * |

| H1b: User involvement ← Negative after-sale service | −0.130 | 0.090 | 0.151 |

| H1c: User involvement ← Negative online shopping platform environment | 0.372 | 0.026 | * |

| H1d: User involvement ← Negative logistics service | −0.005 | 0.026 | 0.848 |

| H2: Negative eWOM motivation ← User involvement | 0.520 | 0.033 | * |

| H3a: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative product quality | 0.502 | 0.021 | * |

| H3b: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative after-sale service | 0.423 | 0.027 | * |

| H3c: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative online shopping platform environment | 0.277 | 0.037 | * |

| H3d: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative logistics service | 0.331 | 0.036 | * |

| RMR | RMSEA | GFI | RFI | CFI | PGFI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original results | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.970 | 0.874 | 0.908 | 0.547 | 0.885 |

| Modified results | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.973 | 0.887 | 0.910 | 0.551 | 0772 |

| Hypotheses and Paths | Load Factor | Standard Error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: User involvement ← Negative product quality | 0.474 | 0.047 | |

| H1c: User involvement ← Negative online shopping platform environment | 0.392 | 0.015 | |

| H2: Negative eWOM motivation ← User involvement | 0.531 | 0.038 | |

| H3a: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative product quality | 0.575 | 0.006 | |

| H3b: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative after-sale service | 0.323 | 0.115 | 0.006 |

| H3c: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative online shopping platform environment | 0.279 | 0.042 | |

| H3d: Negative eWOM motivation ← Negative logistics service | 0.327 | 0.033 |

| Effect | Bias Corrected 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Quality → Negative eWOM motivation | Total effect | 0.232 | 0.689 |

| Indirect effect | 0.015 | 0.292 | |

| Direct effect | 0.086 | 0.577 | |

| Online shopping platform environment → eWOM motivation | Total effect | 0.315 | 0.732 |

| Indirect effect | 0.027 | 0.265 | |

| Direct effect | 0.156 | 0.542 | |

| RMR | RMSEA | GFI | RFI | CFI | PGFI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.912 | 0.522 | 1.216 |

| Hypotheses and Paths | Load Factor | Standard Error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H4: Negative eWOM motivation→ Immediate eWOM communication | 0.553 | 0.022 | |

| H5: Negative eWOM motivation→ Ongoing eWOM communication | 0.401 | 0.017 |

| Interdependent | Independent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | p Value | Variable | Coefficient | p Value |

| Constant term | 0.1491 | 0.1101 | Constant term | −0.0958 | 0.5071 |

| X | 0.9519 | 0.0000 | X | 1.0342 | 0.0000 |

| R2 | 0.8588 | R2 | 0.8392 | ||

| F | 1198.3171 | F | 610.7641 | ||

| Sig.F | 0.0000 | Sig.F | 0.0000 | ||

| Interdependent | Independent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | p Value | Variable | Coefficient | p Value |

| Constant term | 0.0119 | 0.9122 | Constant term | −0.1264 | 0.3946 |

| X | 1.0066 | 0.0000 | X | 1.0460 | 0.0000 |

| R2 | 0.8340 | R2 | 0.8350 | ||

| F | 989.6102 | F | 591.8913 | ||

| Sig.F | 0.0000 | Sig.F | 0.0000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, M. Causes and Behavioral Evolution of Negative Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: Considering the Mediating Role of User Involvement and the Moderating Role of User Self-Construal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010660

He Y, Wu J, Wang M. Causes and Behavioral Evolution of Negative Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: Considering the Mediating Role of User Involvement and the Moderating Role of User Self-Construal. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010660

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Youshi, Jingyan Wu, and Min Wang. 2023. "Causes and Behavioral Evolution of Negative Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: Considering the Mediating Role of User Involvement and the Moderating Role of User Self-Construal" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010660