Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—The Case of the Vršac Mountains Outstanding Natural Landscape, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Area

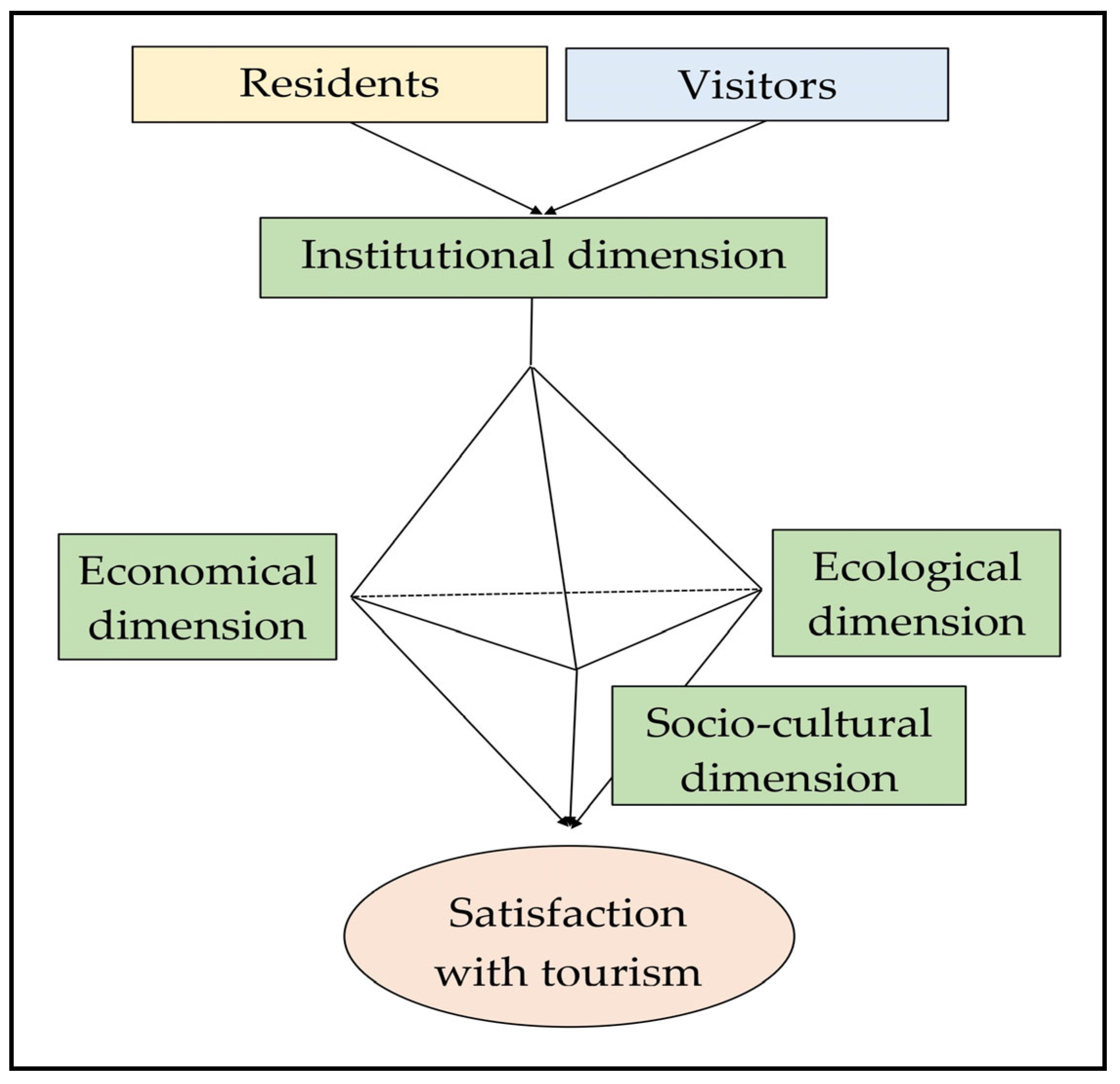

4. Methodology

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The aforementioned research is based on the fundamental principles of sustainable development, the application and successful implementation of which increases the ONL’s opportunity to succeed in developing sustainable tourism and to appear on the tourist market as a sustainable tourism destination. The need for constant education and training of visitors, tourism staff, and the local population, and the allocation of funds for protecting and preserving the area (both its natural and anthropogenic components), should be added to these principles. The results of this research indicate that the protected ONL area has various possibilities for the development of special forms of tourism. The respondents recognized ecological and socio-cultural sustainability as the most important dimensions of sustainability. These data can be used when planning and developing different forms of tourism. Herein, above all, we mean forms of tourism based on natural resources. For the preservation of the ONL, the most significant form of tourism would be ecotourism with ecological and sustainable components. The basis of the study of eco-tourism is the preservation of nature and the protection of environments that provide a special atmosphere for tourists. Additionally, these environments are tourist products, the value of which is known to tourists who are aware of their uniqueness and who will contribute to their overall protection with their actions and the experiences they gain [79]. Certainly, the above-mentioned forms of tourism can only be developed in preserved nature in cooperation with the local community. This is why destinations whose local populations have an active role are of particular importance for sustainable tourism. In such destinations, properly developed tourism creates benefits, while the effects of development mutually interact in different ways. The ONL could be an important destination for sustainable tourism because it has specific natural and social elements that can influence the development of different forms of tourism. In addition to relief, geographical position, and hydrographic potential, the diversity and wealth of autochthonous flora and fauna are important for tourism development. These factors enable the development of education, recreation, excursion, and ecotourism as primary tourism forms. The ONL in Serbia is inhabited by extremely rare bird species, which makes it possible to organize photo safaris or ornithological tourist tours (educational forms of tourism). The population living in the ONL has rich traditions, culture, and cultural and historical heritage, as well as handicrafts, music, national dances, gastronomy, vineyards, orchards, and many other resources. It represents a rich basis for the development of different forms of tourism, such as sustainable, cultural, and event tourism. The two above-mentioned specific forms of tourism have the characteristic of incorporating social motives into their tourist offerings. Together with natural motifs, a high-quality tourist destination can be created, whose main priority would be the protection of the environment and its species.

- (2)

- When it comes to specific tourist products, it is necessary to keep in mind that there are a wide range of services and products intended for different market segments. Tourism development can benefit all users of the protected area. Segmentation, and then, the creation of a specific product for the selected segment or segments is the basis of the market performance of specific tourism forms. An example is the organization of planned groups based on people’s interests. These are small groups who are interested in scientific education and who have specific needs that can be met at the NLO. Those groups can be financed by special sources if they are concerned with research or education. In this way, they directly help to establish the financing of national parks and sustainable development, especially in developing countries [39].

- (3)

- Marketing activities are extremely important for the promotion and development of protected areas. Accordingly, it is important that managers of protected natural assets gain experience of all marketing tools. This is why they must know that the successful implementation of ecological components, the protection of the environment, and giving priority to products that are organized in accordance with ecological standards form the basis for creating the right image [80]. For a long time, sustainable tourism has been a very important use of space, considering the benefits that result from the overall development of tourism [81].

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amidžić, L.; Krasulja, S.; Belij, S. (Eds.) Protected Natural Resources in Serbia; Ministry of Environmental Protection, Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pivac, T. Vinski Turizam Vojvodine; Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, Prirodni-Matematički Fakultet, Departman za Geografiju, Turizam i Hotelijerstvo: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2012. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Maple, L.C.; Eagles, P.F.J.; Rolfe, H. Birdwatchers’ specialisation characteristics and national park tourism planning. J. Ecotourism 2010, 9, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.A.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modelling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, D.; Nunes, L.M. Monitoring and evaluation tool for tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse—Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Sanabria, R.; Skinner, E. Sustainable tourism and ecotourism certification: Raising standards and benefits. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Cutumisu, N. Sustainable tourism development strategy in WWF Pan Parks: Case of a Swedish and Romanian national park. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.S.; Fan, L.; Lu, J. Tourist experience and wetland parks: A case of Zhejiang, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S. Transforming travel: Realising the potential of sustainable tourism. J. Ecotourism 2019, 18, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.M.; Courtney, C.A.; Hamilton, A.T.; Parker, B.A.; Gibbs, D.A.; Bradley, P.; Julius, S.H. Adaptation design tool for climate-smart management of coral reefs and other natural resources. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirakaya, E.; Teye, V.; Sonmez, S. Understanding residents’ support for tourism development in the Central region of Ghana. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelani, P.; Shah, S.A.; Dar, S.N.; Rashid, H. Sustainability constructs of mountain tourism development: The evaluation of stakeholders’ perception using SUS-TAS. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivieso, J.C.; Eagles, P.F.J.; Gila, J.C. Efficient management capacity evaluation of tourism in protected areas. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 1544–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G.; Carr, N.; Lovelock, B. Community participation framework for protected area-based tourism planning. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 13, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Whitty, T.S.; Finkbeiner, E.; Pittman, J.; Bassett, H.; Gelcich, S.; Allison, E.H. Environmental Stewardship: A Conceptual Review and Analytical Framework. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, C.; Swait, J.; Vij, A.; Thiene, M. Determinants of recreational activities choice in protected areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K. Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.A.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism, Ecology, Impacts, and Management; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A.; Sparrowhawk, J. Understanding the motivations of ecotourists: The case of trekkers in Annapurna, Nepal. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, S. Residents’ satisfaction with sustainable tourism: The moderating role of environmental awareness. Tour. Crit. 2022, 3, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F. Managing for visitor experiences in protected areas: Promising opportunities and fundamental challenges. Park. Int. J. Prot. Areas Manag. 2006, 16, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Ecological indicators of tourist impacts in parks. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Miller, G. Transforming societies and transforming tourism: Sustainable tourism in times of change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, R.E.; Guerreiro, J.; Ventura, M.A. Demand of the tourists visiting protected areas in small oceanic islands: The Azores case-study (Portugal). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 16, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The evolution of sustainable development and sustainable tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C.M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, R. Latin American ecotourism: What is it? Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F. Tourism in National Parks and Protected Areas; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leask, A. Progress in visitor attraction research: Towards more effective management. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Indigenous peoples and tourism: The challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Cortés, M.; Maya, J.A.A. Identifying and structuring values to guide the choice of sustainability indicators for tourism development. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3074–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgadoa, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges de Lima, I.; Green, R.J. Wildlife Tourism, Environmental Learning and Ethical Encounters, Ecological and Conservation Aspects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M.L.; Cabrera, A.T.; Gomez del Pulgar, M.L. The potential role of cultural ecosystem services in heritage research through a set of indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, A.; Lagarias, A.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Development of a tourism carrying capacity index (TCCI) for sustainable management of coastal areas in Mediterranean islands—Case study Naxos, Greece. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 216, 105978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.L.M.; Moore, S.A.; Wallington, T.J.; Dowling, R. Ecotourism in Bako National Park, Borneo: Visitors’ perspectives on environmental impacts and their management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Moisey, R.N.; Nickerson, N.P. What should tourism sustain? The disconnect with industry perceptions of useful indicators. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schianetz, K.; Kavanagh, L. Sustainability indicators for tourism destinations: A complex adaptive systems approach using systemic indicator systems. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.C. Sustainable tourism indicators: Selection criteria for policy implementation and scientific recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; White, V.; McCrum, G.; Scott, A.; Hunter, C. Measuring responsibility: An appraisal of a Scottish national park’s sustainable tourism indicators. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.; Gursoy, D. A multifaceted analysis of tourism satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twining-Ward, L.; Butler, R. Implementing STD on a small island: Development and use of sustainable tourism development indicators in Samoa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, M.; Kruger, M.; Saayman, M. Determinants of visitor length of stay at three coastal national parks in South Africa. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowinska-Świerkosz, B.; Chmielewski, T.J. Comparative assessment of public opinion on the landscape quality of two biosphere reserves in Europe. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banos-Gonzales, I.; Martinez-Fernandez, J.; Esteve-Selma, M.A. Using dynamic sustainability indicators to assess environmental policy measures in Biosphere Reserves. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Hsieh, H.P. Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying core indicators of sustainable tourism: A path forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučetić, A. Importance of environmental indicators of sustainable development in the transitional selective tourism destination. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huayhuaca, C.; Cottrell, S.; Raadik, J.; Gradl, S. Resident perceptions of sustainable tourism development: Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2010, 3, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Roemer, J.M. Resident satisfaction with sustainable tourism: The case of Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, C.L. Cautionary thoughts on IUCN protected area management categories V–VI. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 3, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, L.; Pavić, D.; Stojanović, V.; Tomić, P.; Romelić, J.; Pivac, T.; Košić, K.; Besermenji, S.; Kicošev, S. Protected Natural Resources and Ecotourism in Vojvodina; Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, Prirodno-Matematički Fakultet, Departman za Geografiju, Turizam i Hotelijerstvo: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bjeljac, Ž.; Romelić, J. Tourism on Vršac Mountains; Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić“, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Environmental space and the prism of sustainability: Frameworks for indicators measuring sustainable development. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgadir, F.A.A.; Halis, M.; Halis, M. Tourism stakeholders’ attitudes toward sustainable developments: Empirical research from Shahat city. Ottoman J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2017, 2, 182–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Shapovalova, A.; Lan, W.; Knight, D.W. Resident support in China’s new national parks: An extension of the Prism of Sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Cottrell, S.P. A sustainable tourismframework formonitoring residents’ satisfaction with agritourism in Chongdugou Village, China. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2008, 1, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Ali, F.; Ragavan, N.A.; Manhas, P.S. Sustainable tourism and resulting resident satisfaction at Jammu and Kashmir, India. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 7, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Rodger, K.; Pearce, J.; Chan, K.L.J. Visitor satisfaction with a key wildlife tourism destination within the context of a damaged landscape. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Shen, F. Modeling resident perceptions of sustainable tourism development: Applications in Holland and China. J. China Tour. Res. 2007, 3, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Raadik, J. Socio-cultural benefits of PAN Parks at Bieszscady National Park, Poland. Matkailututkimus 2008, 1, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, S.; Tešin, A.; Božović, T.; Milošević, D. Residents’ perceptions of and satisfaction with tourism development: A case study of the Uvac Special Nature Reserve, Serbia. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 21, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoaldo, P.; Serra, J.; Marujo, N.; Alves, J.; Gonçalves, A.; Cabeça, S.; Duxbury, N. Profiling the participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium sized cities and rural areas from Continental Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Weiler, B.; Assaker, G. Effects of interpretive guiding outcomes on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, S.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Jasrotia, A. Sustainable tourism and residents’ satisfaction: An empirical analysis of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Delhi (India). J. Hosp. Appl. Res. 2023, 18, 70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Armenski, T.; Pavluković, V.; Pejović, L.; Lukić, T.; Đurđev, B. Interaction between tourists and residents: Influence on tourism development. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 173, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, T.M. Sustainable ecotourism in Amazonia: Evaluation of six sites in Southeastern Peru. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, J.F.; Dieperink, C.; Miranda, M. Ecotourism as a development strategy: Experiences from Costa Rica. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J. Research priorities in park tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Escaping the jungle: An exploration of the relationships between lifestyle market segments and satisfaction with a nature based tourism experience. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2004, 5, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.C.; Sirakaya, E. Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2005, 43, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, G.; Grigoroudis, E. Visitors’ satisfaction, perceptions and gap analysis: The case of Dadia–Lefkimi–Souflion National Park. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: A longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Vieira, N.; Pocinho, M. Exploring the behavioural approach for sustainable tourism. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 8, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, M.; Viljoen, A.; Saayman, M. Who visits the Kruger National Park and why? Identifying target markets. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Yi Mal Li, R. Tourist satisfaction, willingness to revisit and recommend, and Mountain Kangyang Tourism Spots sustainability: A structural equation modelling approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Residents (n = 789) | Visitors (n = 630) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of Sustainable Tourism | α | Mean | α | Mean |

| Institutional Dimension | 0.603 | 3.09 | 0.600 | 3.11 |

| Visitors are guided through the protected area by trained guides and representatives of the local community | 3.04 | 3.12 | ||

| Visitors in the protected area can see the local products (wineries, ethno-houses, handicrafts, local enterprises, etc.) | 3.02 | 3.09 | ||

| In the protected area, the manager’s instructions on nature protection and visitors’ activities are followed | 3.14 | 3.12 | ||

| Visitors are provided with information that reflects the history of the reserve, population, and settlements | 3.17 | 3.13 | ||

| Ecological Dimension | 0.756 | 3.46 | 0.789 | 3.84 |

| There is a joint role of visitors and residents in protecting the area | 3.56 | 3.80 | ||

| There are facilities, services, and activities available to visitors and the local community in the protected area | 3.67 | 4.12 | ||

| There are tourist facilities that do not impact the environment | 3.14 | 3.62 | ||

| Economic Dimension | 0.653 | 3.45 | 0.662 | 3.46 |

| Tourism in the protected area benefits the local community | 3.00 | 3.06 | ||

| Tourism in the protected area supports the local economy | 3.14 | 3.23 | ||

| Tourism in the protected area contributes to the employment of the local population | 2.97 | 2.88 | ||

| Local products are available to visitors | 4.01 | 4.00 | ||

| Visitors support the prices of domestic products | 4.15 | 4.13 | ||

| Socio-cultural Dimension | 0.715 | 4.01 | 0.672 | 3.99 |

| Visitors are interested in home-made products and crafts | 4.15 | 4.09 | ||

| Visitors are in contact with residents | 3.56 | 3.69 | ||

| Visitors are interested in local traditions and customs | 4.17 | 3.94 | ||

| Visitors visit local cultural attractions and events | 4.52 | 4.09 | ||

| Visitors are interested in historical sites | 3.69 | 4.12 | ||

| Index | Residents (n = 789) | Visitors (n = 630) | ||

| α | Mean | α | Mean | |

| 0.617 | 3.82 | 0.687 | 3.94 | |

| Tourism in this protected area produces various benefits for me | 3.54 | 3.67 | ||

| It is important to me that there is sustainable tourism in this protected area | 4.27 | 3.92 | ||

| Tourism has contributed to the increased attractiveness of this protected area | 4.31 | 4.14 | ||

| I am satisfied with tourism in this area | 3.18 | 4.03 | ||

| Satisfaction with Tourism Items | Residents | Visitors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β 1 | p-Value | β 1 | p-Value | |

| Institutional dimension | 0.184 | 0.011 | 0.211 | 0.031 |

| Ecological dimension | 0.277 | 0.027 | 0.251 | 0.054 |

| Economic dimension | 0.156 | 0.006 | 0.201 | 0.037 |

| Socio-cultural dimension | 0.254 | 0.034 | 0.233 | 0.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trišić, I.; Nechita, F.; Ristić, V.; Štetić, S.; Maksin, M.; Atudorei, I.A. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—The Case of the Vršac Mountains Outstanding Natural Landscape, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Sustainability 2023, 15, 7760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107760

Trišić I, Nechita F, Ristić V, Štetić S, Maksin M, Atudorei IA. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—The Case of the Vršac Mountains Outstanding Natural Landscape, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107760

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrišić, Igor, Florin Nechita, Vladica Ristić, Snežana Štetić, Marija Maksin, and Ioana Anisa Atudorei. 2023. "Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—The Case of the Vršac Mountains Outstanding Natural Landscape, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia)" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107760

APA StyleTrišić, I., Nechita, F., Ristić, V., Štetić, S., Maksin, M., & Atudorei, I. A. (2023). Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—The Case of the Vršac Mountains Outstanding Natural Landscape, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Sustainability, 15(10), 7760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107760