Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’ through Participatory Ecological Storytelling: From Human-Centered to Planet-Centered Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framing of Empathy for the Planet

1.2. Empathy for the Planet in the Design Practice

1.3. Empathy for the Planet in Stories: The Role of Imagination, Anthropomorphism, Human Bridges, and Identification

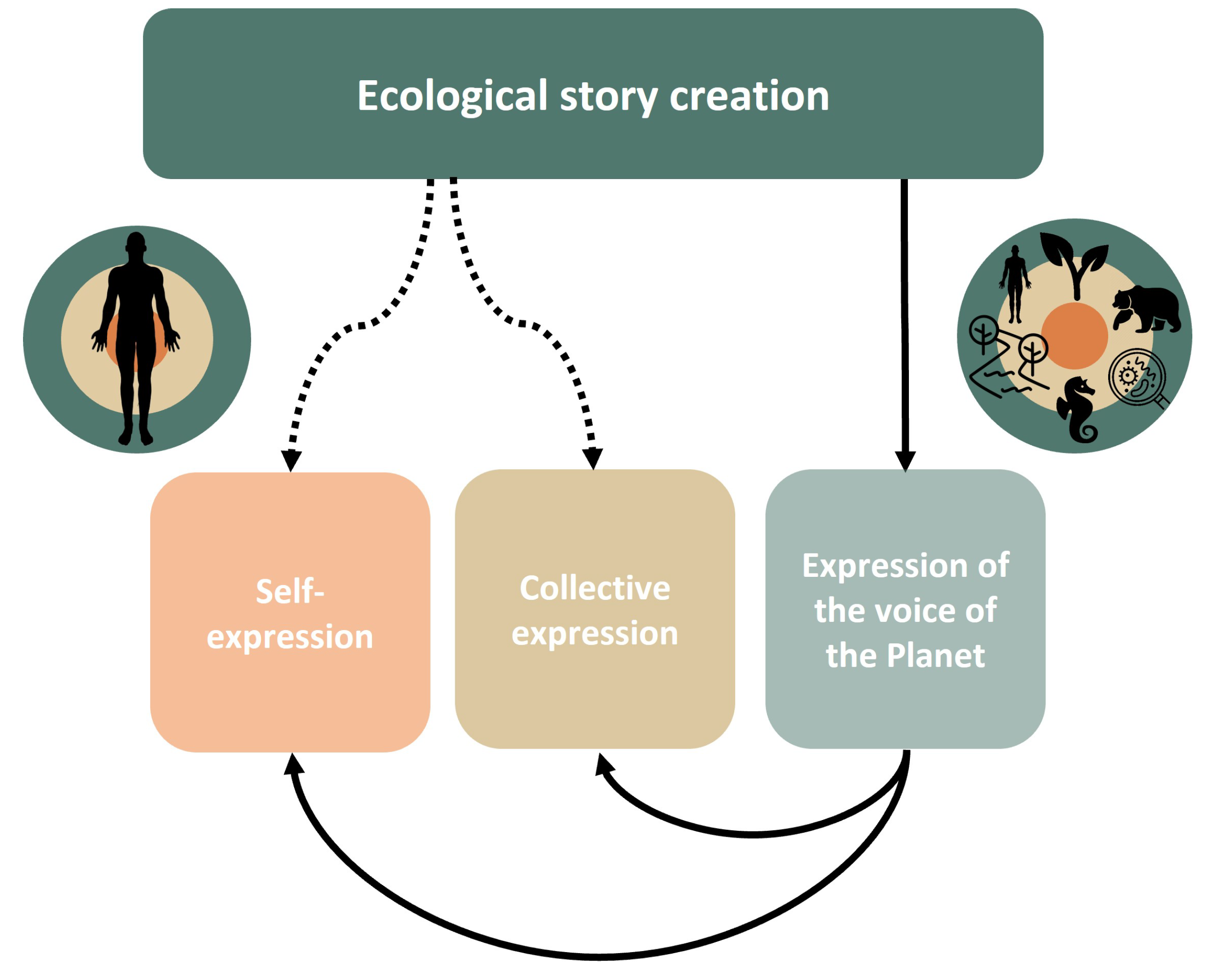

1.4. Ecological Self-Narratives

1.5. Ecological Collective Narratives

1.6. Principles Guiding Our Participatory Ecological Storytelling Method

- (1)

- Planetary character: the character of the story can be human, animal, vegetal, natural, object, spiritual, metaphorical, etc., singular, a group, or an ecosystem. The workshop participants are free to choose the type of character and whether to use anthropomorphism or not. The character’s journey in the story illustrates the story theme—the “main message”—related to environmental challenges or sustainable solutions. The characters are developed through a Planetary persona template.

- (2)

- Character depth: building granular character personas with motivations, history, a rich inner world, and positive and negative sides is key to creating compelling characters [49]. It enables imagining their reactions and decision rationales along with the events of the story, which is essential to assigning them narrative agency.

- (3)

- Playfulness: participatory storytelling presents similarities with play in its cooperative, non-hierarchical, instinctive, and improvised dynamics and in overcoming divisions of nature and culture [3]. Such dynamics yield original ideas and the expression of tacit knowledge (i.e., knowledge gained through personal experiences) as story creators encourage each other to be creative, expansive, humorous, and honest [38,49]. The intrinsic experience of building the story and engaging with others, the character, and their world is more important than the resulting story [7]. Participants are encouraged to build on each other’s suggestions, to try, to be imperfect, to use humor, and to share personal experiences.

- (4)

- Open plot: we do not enforce the use of antagonists or villains or pre-defined story arcs such as the Campbell heroes journey in order not to nudge the stories into a conflictual story canon that may reinforce the human/nonhuman antagonism [3]. The story structure is as open as possible while using well-known narrative components to make it easy to create the story [120]: participants are guided to create story arcs with a beginning, a middle, and an end, with the middle part dynamized by the struggles of the main protagonists.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure of the Workshops

- -

- Workshop 1 involved a group of 31 students in the first year of their industrial design education at a Dutch university, was conducted online, and took place in January 2022. The students were taking a course aimed at developing their critical thinking, and the workshop was an element of that course.

- -

- Workshop 2, which involved 10 participants, was conducted in real life during an international design conference in July 2022. The participants were professionals or senior students (Master’s, PhD) in the field of design and art.

- -

- Workshops 3 and 4 were conducted at a large multinational in February 2023 with 25 people each, with roles in marketing, business, design, and innovation.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

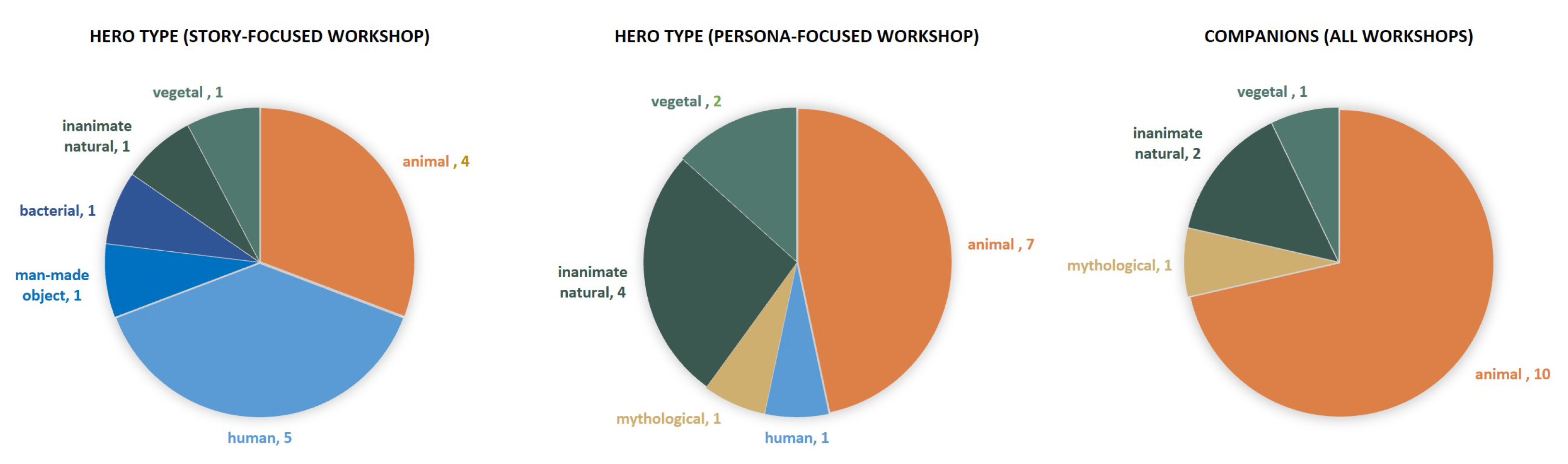

3.1. Story Characters

3.2. Story Themes and Endings

3.3. Creation of Empathy for the Planet

“In our story we tried to communicate empathy for the sea life by giving fishermen the bad guy role and showing how abruptly they can destroy sea life animals’ lives. Leaving the animals in pain.”

“We tried to make the character Nemo, which everyone loves, be very pathetic. His house is destroyed, his home is destroyed and all his friends are gone. And with the context that the world and men have done all this, you start to think about Nemo and really realize what we do. You feel guilty for what you did to him, even if it’s just a fictional story.”

“The story should create a feeling of familiarity, and causes people to think as the main character. It will let people ask questions and let them doubt about their own purchasing habits.”

“[The story] generates empathy for the innovative woodworker and his ethics. You feel like that is the way forward and that the cutting of new trees is not always necessary.”

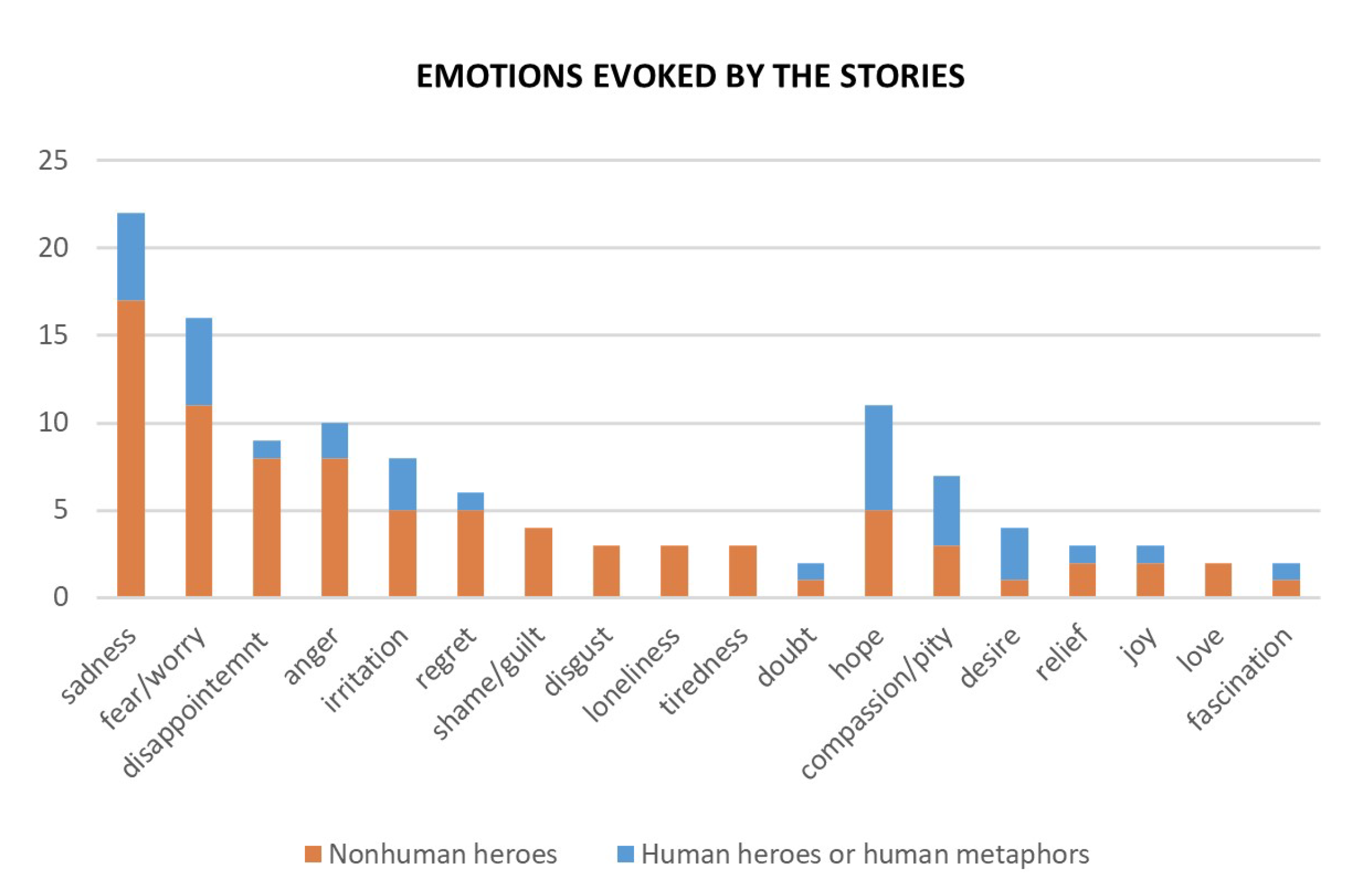

3.4. Emotions Evoked by Stories

3.5. Experience of the Story Co-Creation Process

3.6. Short-Term Change in Perspective and Behavioral Intention after the Workshop

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms for Creating and Experiencing Empathy for the Planet through Participatory Ecological Storytelling

4.2. Positioning of the Findings on Participatory Ecological Storytelling in Existing Knowledge

4.3. Positioning of Empathy for the Planet in Post-Anthropocentric Thinking and a Preliminary Definition

4.4. Limitations of This Study and Suggestions for Method Improvement

4.5. Applications of Participatory Ecological Storytelling and Empaty for the Planet in Sustainable Design Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. A Selection of Illustrative Personas and Stories

References

- Alhaddi, H. Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O., Jr. The Significance of Children and Animals: Social Development and Our Connections to Other Species, 2nd Revised ed.; Purdue Univ. Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Donly, C. Toward the Eco-Narrative: Rethinking the Role of Conflict in Storytelling. Humanities 2017, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Light, A.; Kamihira, T. Expanding participation to design with more-than-human concerns. In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference, Manizales, Colombia, 15–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Forlano, L. Posthumanism and design. She Ji 2017, 3, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselova, E.; Gaziulusoy, İ. Bioinclusive Collaborative and Participatory Design: A Conceptual Framework and a Research Agenda. Des. Cult. 2022, 14, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, E.; Meinel, C. Empathy via design thinking: Creation of sense and knowledge. In Design Thinking Research; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kouprie, M.; Visser, F.S. A framework for empathy in design: Stepping into and out of the user’s life. J. Eng. Des. 2009, 20, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, İ. Design for Sustainability: A Multi-Level Framework from Products to Socio-Technical Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loveday, J.; Morrison, G.M.; Martin, D.A. Identifying Knowledge and Process Gaps from a Systematic Literature Review of Net-Zero Definitions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastling, T.; Charnley, F.; Moreno, M. Design for Circular Behaviour: Considering Users in a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, E.M.; Guckian, M.L. Climate change communication: Challenges, insights, and opportunities. In Psychology and Climate Change; Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms, D.; Barati, B.; Winters, A.; Bruns, M. Life Centered Design: Unpacking a Post-humanistic Biodesign Process. In Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the International Association of Societies of Design Research, Hong Kong, China, 5–9 December 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X. Integrating people-centered and planet-centered design: In conversation with Elizabeth Murnane. XRDS Crossroads ACM Mag. Stud. 2021, 28, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, M.; Roversi, S.; Jatwani, C.; Tiriduzzi, M. Human and planet centered approach: Prosperity thinking in action. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoewa, V. Radical Participatory Design: Awareness of Participation. J. Aware.-Based Syst. Chang. 2022, 2, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlano, L. Decentering the human in the design of collaborative cities. Des. Issues 2016, 32, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L. I, River?: New materialism, riparian non-human agency and the scale of democratic reform. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2017, 58, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccardi, E.; Cila, N.; Speed, C.; Caldwell, M. Thing ethnography: Doing design research with non-humans. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, Australia, 4–8 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, M.; Pálsson, G. Ethnography Beyond the Human: The ‘Other-than-Human’ in Ethnographic Work. Ethnos 2019, 86, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I. How Concerned, Afraid and Hopeful Are We? Effects of Egoism and Altruism on Climate Change Related Issues. Psychology 2013, 4, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H.; Gupta, S.; Bosetti, V.; Cooke, R.M.; Duong, M.H.; Held, H.; Llanes-Regueiro, J.; Patt, A.; Shittu, E.; Weber, E.U.; et al. Integrated Risk and Uncertainty Assessment of Climate Change Response Policies. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 117–172. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, A.D.; Bekoff, M.; Batavia, C.; Nelson, M.P.; Ramp, D. Summoning compassion to address the challenges of conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batavia, C.; Nelson, M.P.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Jones, M.S.; Yanco, E.; Ramp, D.; Bekoff, M.; Wallach, A.D. Emotion as a source of moral understanding in conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramp, D.; Bekoff, M. Compassion as a practical and evolved ethic for conservation. BioScience 2015, 65, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. What shapes perceptions of climate change? New research since 2010. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Clarke, J. Talking Climate: From Research to Practice in Public Engagement; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniek-Tobasco, A.; McCormick, S.; Rimal, R.; Harrington, C.; Shafer, M.; Shaikh, H. Communicating climate change through documentary film: Imagery, emotion, and efficacy. Clim. Chang. 2019, 154, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon Thompson, S.C.; Barton, M.A. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1994, 14, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Khalil, K.A.; Wharton, J. Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. Curator Mus. J. 2018, 61, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E. The Storyworld Accord: Econarratology and Postcolonial Narratives; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2015; pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar]

- Toivonen, H.; Caracciolo, M. Storytalk and complex constructions of nonhuman agency: An interview-based investigation. Narrat. Inq. 2022, 33, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaerts, L.; Caracciolo, M.; Herman, L.; Vervaeck, B. The Storied Lives of Non-Human Narrators. Narrative 2014, 22, 68–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Latorre, S.; Mourey, F. Promoting creative imagination of non-expressed needs: Exploring a combined approach to enhance design thinking. Creat. Stud. 2018, 11, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlström, A. Storytelling in Design: Defining, Designing, and Selling Multidevice Products; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lichaw, D. The User’s Journey: Storymapping Products that People Love; Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, P. Design as storytelling. TechTrends 2006, 50, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesenbery, W.; Brooks, K. Storytelling for User Experience—Crafting Stories for Better Design; Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Genco, N.; Johnson, D.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Seepersad, C. A Study of the effectiveness of the Empathic Experience Design creativity technique. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 28–31 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, D.; Rauch, T.; Redpath, S.; Ruettinger, S. The use of stories in user experience design. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2002, 14, 503–534. [Google Scholar]

- Frawley, J.K.; Dyson, L.E. Animal personas: Acknowledging non-human stakeholders in designing for sustainable food systems. In Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: The Future of Design, Sydney, Australia, 2–5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sznel, M. Your Next Persona Will Be Non-Human—Tools for Environment-Centered Designers. 2020. Available online: https://uxdesign.cc/tools-for-environment-centered-designers-actant-mapping-canvas-a495df19750e (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Sands, D. Animal Writing: Storytelling, Selfhood and the Limits of Empathy; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Bellon, D.; Kane, A. Natural history films raise species awareness—A big data approach. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M.; Mara, M. The persuasive influence of a fictional character’s trustworthiness. J. Commun. 2013, 63, 912–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgorn, E.; Hendriks, M.; Geurts, L.; Bakker, C. A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersie, A. Storytelling for a Greener World; Hawthorn Press: Stroud, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmann, S. “Once upon a time…” Eliciting energy and behaviour change stories using a fairy tale story spine. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Dong, H.; Yuan, S. Empathy in design: A historical and cross-disciplinary perspective. In Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conference on Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, J. A note on empathy. New Ideas Psychol. 1997, 15, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, T. Empathy as faux ethics. Retrieved 4 January 2017. Available online: https://www.epicpeople.org/empathy-faux-ethics/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Mathews, F. Towards a deeper philosophy of biomimicry. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumwood, V. The politics of reason: Towards a feminist logic. Australas. J. Philos. 1993, 71, 436–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D.J. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nanson, A. Storytelling and Ecology: Empathy, Enchantment and Emergence in the Use of Oral Narratives; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dolby, N. Rethinking Multicultural Education for the Next Generation: Rethinking Multicultural Education for the Next Generation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kuleta-Hulboj, M.; Aleksiak, D. Looking for a better future? Reconstruction of global citizenship and sustainable development in Polish mational curriculum. In Educational Response, Inclusion and Empowerment for SDGs in Emerging Economies: How Do Education Systems Contribute to Raising Global Citizens? Öztürk, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. Utilising place-based learning through local contexts to develop agents of change in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability. Educ. 3-13 2019, 47, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, J.; Gilchrist, E. Creating empathy for the more-than-human under 2 degrees heating. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, A.; Dong, A. To empathise or not to empathise? Empathy and its limits in design. Des. Stud. 2019, 65, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battarbee, K.; Koskinen, I. Co-experience: User experience as interaction. CoDesign 2005, 1, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, J.; Montgomery, H. Empathy as an interpersonal phenomenon. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2003, 20, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, B.M.; Brown, S.J.; Taylor, L.; Howat, D.J. Empathy: A review of the concept. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; Draper, S.W. User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard, A.S.; Lerner, M.D.; Hopkins, E.J.; Dore, R.A.; Smith, E.D.; Palmquist, C.M. The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keen, S. Empathy and the Novel; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.; Hirskyj-Douglas, I.; Pons, P. Designing for Animals: Defining Participation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction, Atlanta, GA, USA, 4–6 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Bardzell, S.; Bardzell, J. Designing for Cohabitation: Naturecultures, Hybrids, and Decentering the Human in Design. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwhuis, T. Designing for Animals. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maple, T.L.; Perdue, B.M. Designing for animal welfare. In Zoo Animal Welfare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, J.; Greene, T.; Wang, J.-C.; Kuo, P.-Y. Beyond Human-Centered Design: Proposing a Biocentric View on Design Research Involving Vegetal Subjects. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, A.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Nicenboim, I.; Søndergaard, M.L.; Lupetti, M.; Key, C.; Speed, C.; Lockton, D.; Giaccardi, E.; Grommé, F.; et al. Making Everyday Things Talk: Speculative Conversations into the Future of Voice Interfaces at Home. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, M. Towards a more-than-human participatory research. In Participatory Research in More-than-Human Worlds; Bastian, M., Jones, O., Moore, N., Roe, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noorani, T.; Brigstocke, J. More-than-Human Participatory Research; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, E. The Storyworld Accord: Econarratology and Postcolonial Narratives. By Erin James. ISLE Interdiscip. Stud. Lit. Environ. 2017, 24, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoleris, A.; Stripple, J.; Tenngart, P. Narrating climate futures: Shared socioeconomic pathways and literary fiction. Clim. Chang. 2017, 143, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, S. Getting to the Heart of Climate Change through Stories. In Universities and Climate Change; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow, M. Ecological Identity: Becoming a Reflective Environmentalist; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Veland, S.; Scoville-Simonds, M.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; Schorre, A.; Khoury, A.; Nordbø, M.; Lynch, A.; Hochachka, G.; Bjørkan, M. Narrative matters for sustainability: The transformative role of storytelling in realizing 1.5 °C futures. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpu, V. What Is Public Engagement and How Does It Help to Address Climate Change? A Review of Climate Communication Research. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezzi, M.; Janda, K.B.; Rotmann, S. Using stories, narratives, and storytelling in energy and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising, J.; Tedesco, M.; Piontek, F.; Stainforth, D.A. The missing risks of climate change. Nature 2022, 610, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkoreit, M. The promise of climate fiction: Imagination, storytelling, and the politics of the future. In Reimagining Climate Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- von Mossner, A.W. Vulnerable lives: The affective dimensions of risk in young adult cli-fi. Textual Pract. 2017, 31, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkowitz, B.; Speiser, M.; Harp, G.; Hodge, C.; Krygsman, K. American Climate Values 2014: Psychographic and Demographic Insights; ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Tunn, V.; Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Consumers in the circular economy. In Handbook of the Circular Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Marketing approaches for a circular economy: Using design frameworks to interpret online communications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daae, J.; Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Dimensions of Behaviour Change in the context of Designing for a Circular Economy. Des. J. 2018, 21, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, A. Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren Leavenworth, M.; Manni, A. Climate fiction and young learners’ thoughts—A dialogue between literature and education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.B. ‘At the heart of human politics’: Agency and responsibility in the contemporary climate novel. Environ. Politics 2022, 31, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D.J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rae Westbury, H.; Neumann, D.L. Empathy-related responses to moving film stimuli depicting human and non-human animal targets in negative circumstances. Biol. Psychol. 2008, 78, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Tong, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y. Anthropomorphic Strategies Promote Wildlife Conservation through Empathy: The Moderation Role of the Public Epidemic Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.O.; Whitmarsh, L.; Mac Giolla Chríost, D. The association between anthropomorphism of nature and pro-environmental variables: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, V. Animal Wise: The Thoughts and Emotions of Our Fellow Creatures; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, H.A. The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism among the Primates. Innov. J. 2013, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- James, E. Nonhuman Fictional Characters and the Empathy-Altruism Hypothesis. Poet. Today 2019, 40, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, K.U. Eco-Narratives. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory; Herman, D., Jahn, M., Ryan, M.-L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 129–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Weimann-Saks, D.; Mazor-Tregerman, M. Does character similarity increase identification and persuasion? Media Psychol. 2018, 21, 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Williams, H.T.P.; Kurz, T.; Wiersma, B.; Boykoff, M. Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J.S. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.; Nisbet, E. Boomerang Effects in Science Communication How Motivated Reasoning and Identity Cues Amplify Opinion Polarization About Climate Mitigation Policies. Commun. Res. 2012, 39, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, D.W.; Phillips, W.J.; Cooksey, R.; Reser, J.P.; Nunn, P.; Marks, A.D.G.; Loi, N.M.; Watt, S.E. Preaching to different choirs: How to motivate dismissive, uncommitted, and alarmed audiences to adapt to climate change? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, B.; Shallcross, L.; Wilson, M.; Fuller, C.; Hayward, A. Storytelling as a Research Tool Used to Explore Insights and as an Intervention in Public Health: A Systematic Narrative Review. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschen, J.-A.; Ison, R. Narrative research in climate change adaptation—Exploring a complementary paradigm for research and governance. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C. Informing decision making on climate change and low carbon futures: Framing narratives around the United Kingdom’s fifth carbon budget. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, R. From What Is to What If: Unleashing the Power of Imagination to Create the Future We Want; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O Brien, K.L. Climate change and social transformations: Is it time for a quantum leap? WIREs Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, M.; Heinemeyer, C. Storytelling, story-retelling, storyknowing: Towards a participatory practice of storytelling. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2016, 21, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Giuliani, A. A Narrative Perspective on Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 38, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Butler, R.; Day, R.J.; Goodbody, A.H.; Llewellyn, D.H.; Rohse, M.; Smith, B.T.; Tyszczuk, R.A.; Udall, J.; Whyte, N.M. Gathering around stories: Interdisciplinary experiments in support of energy system transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Corner, A. Using Narrative Workshops to socialise the climate debate: Lessons from two case studies—Centre-right audiences and the Scottish public. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altekruse, J.; Fischer, D. Digitally-Enhanced Learning through Collaborative Filmmaking and Storytelling for Sustainable Solutions. In Digitally-Enhanced Learning through Collaborative Filmmaking and Storytelling for Sustainable Solutions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.D.; Anderson Crow, D. How can we use the ‘science of stories’ to produce persuasive scientific stories? Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, G.; MacEwan, E. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art; Foresman Scott: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbers, T.; De Wit, J.B.F.; Appel, M. Transportation into narrative worlds and the motivation to change health-related behavior. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 4886–4906. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, M.C. Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2009, 51, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, T. Common Cause: The Case for Working with Our Cultural Values; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, C. The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, S.J.; Boykoff, M.; Niemeyer, S.; Day, S.A. On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Gustafson, A.; Jensen, R. Framing Climate Change: Exploring the Role of Emotion in Generating Advocacy Behavior. Sci. Commun. 2018, 40, 442–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyckerelle, M. Game-Based Approaches to Climate Change Education: A Lever for Change? The Case of Climate Fresk-Sverige. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, R.; Green, M. The Role of a Narrative’s Emotional Flow in Promoting Persuasive Outcomes. Media Psychol. 2014, 18, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, A. Perspective and use of empathy in design thinking. In Proceedings of the ACHI, the 8th International Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions, Lisbon, Portugal, 22–27 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ienna, M.; Rofe, A.; Gendi, M.; Douglas, H.E.; Kelly, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Callen, A.; Klop-Toker, K.; Scanlon, R.J.; Howell, L.G.; et al. The Relative Role of Knowledge and Empathy in Predicting Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, L. Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethic for Our Relationships with Animals; Lantern Books: Lagos, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Mayerson, M.; Gustafson, A.; Leiserowitz, A.; Goldberg, M.H.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Ballew, M. Environmental Literature as Persuasion: An Experimental Test of the Effects of Reading Climate Fiction. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, D.; Buganza, T.; Bellis, P.; Magnanini, S.; Press, J.; Verganti, R.; Zasa, F. Story-making to nurture change: Creating a journey to make transformation happen. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 427–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, D. Storyworld/Umwelt: Nonhuman Experiences in Graphic Narratives. SubStance 2011, 40, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgorn, E.; Hendriks, M. Storytelling for systems design—Embedding and communicating complex and intangible data through narratives. In Proceedings of the Relating Systems Thinking & Design (RSD) Symposium, Delft, The Netherlands, 2–6 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackmann, H.; Moser, S.C.; St. Clair, A.L. The social heart of global environmental change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 653–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Johnson Zawadzki, S. The value of what others value: When perceived biospheric group values influence individuals’ pro-environmental engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: What more is there to say? WIREs Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malena-Chan, R.A. Making Climate Change Meaningful: Narrative Dissonance and the Gap between Knowledge and Action. Master’s Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. Narrative: An ontology, epistemology and methodology for pro-environmental psychology research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step in Workshop Process | Story-Focused Workshops | Persona-Focused Workshops |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | We presented a recap of storytelling theory basics (narrative transportation, role of empathy and mental imagery, basic story arc structure, building blocks for a story character, tips for creative writing) [121,122] and high-level examples of ecological stories (wildlife documentaries, fictional movies, personal stories, traditional tales) [47,50]. | |

| Persona creation exercise | Collectively (in groups of 2–4), participants were asked to discuss and write down:

| Individually, participants were asked to think about their character and to write:

|

| Story creation exercise | Participants in groups built the story arc for their persona by filling in keywords or short sentences in a story template. The template structures the story into a beginning, a middle and an end:

| |

| Sharing | Stories were written as a short text and in workshop 2 were also verbally shared. | Stories were written as a postcard from the character to humans. |

| Closure | An open discussion was facilitated where participants shared their experiences and learnings during the story creation and reflected on possible benefits of the method for their line of work. | |

| Total workshop duration | 3–4 h | 2 h |

| Theme | Number of Stories Mentioning the Theme | Sub-Themes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in All Workshops | in Story- Focused Workshops | in Persona-Focused Workshops | ||

| Human/nature antagonism | 24 | 69% | 100% |

|

| Human individualism | 11 | 54% | 33% |

|

| Union is strength | 10 | 54% | 20% |

|

| Learning from nature | 10 | 46% | 20% |

|

| Humans taking action to solve the issue | 6 | 38% | 7% |

|

| Experience during Persona and Story Creation | Summary of Experience Element | Number of Respondents Mentioning the Element | Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in Story-Focused Workshops | in Persona-Focused Workshops | |||

| Collaboration and exchange | 34 respondents expressed that the story co-creation stimulates collaboration, exchange of ideas and perspectives. The process challenges them to listen to and embrace suggestions, to consider different opinions and perspectives (including those from people who do not share their values), to look at problems differently. As a result, the process helps to go more in depth with ideas and to improve their reflection. Several respondents mentioned that it is a good team building exercise as it connects people and a good medium to facilitate a discussion about the environment and sustainability. | 80% | 48% | “It was a great way to connect our ideas and dive deeper in the problem.” “My team was very diverse and being able to execute a task with people who thought so differently was fascinating, exciting and taught me to compromise on expectations.” “The story is a really strong method to get organizations reflect on their current behavior, and at least start the conversation. Love the way storytelling creates the opportunity to discuss change and innovation in the form of metaphors. This way it may at first not be as confronting and stimulate co-creation from different perspectives.” “I really relate to the story because I’ve been to Malaysia and expected only beautiful things but saw a lot of shocking things, like pollution, dead coral reefs and big palm tree plantations. I’ve seen the jungle before and there I saw it getting destroyed right before my eyes. [...] I realized that the people that don’t share the same mindset as me (wanting to contribute to a more sustainable world) don’t have it because they haven’t seen it up close like I did.” |

| Connection to characters | 23 respondents said that the persona creation exercise made them see the world from the character’s perspective and feel closer to them. This was for many a new experience. Being immersed in the creative process during the workshop, relating to personal experiences and memories, and assigning human attributes to nonhuman personas helped them creating this connection. Many in the persona-focused workshops mentioned that the detailed persona templates pushed them to go in depth, inspired them and triggered their imagination. | 23% | 76% | “Personally, it was a bit of an eye opener, we don’t frequently think of being empathetic with our Planet (really putting ourselves in its shoes).” “I like the idea that we were asked to get into the head of the persona and think like we are them. I loved this experience as it was eye-opening.” “To me the creation of the persona was really a super valuable experience and the most interesting part of the workshop. Thinking about what the persona sees and feels really helps to enable an ecosystem mindset, thinking about all the connections the plant, animal or else has in this world and how all actions have impact. Very emotional exercise.” “I liked realizing how it changes the way one thinks about parts of nature, which is in a more personalized way. This increases the felt proximity to the things that surround us. They start playing sort of a role in our life more.” “I used my memories of spending time in the ocean to build a story that could reflect the ocean’s feelings.” |

| Creativity and playfulness | 18 respondents associated the entertaining aspect (the word ‘fun’ came back in most of these answers) to creativity in the process. They see this combination as a motor for new ideas: they enjoyed listening and building upon others’ ideas and being surprised by their creativity. | 23% | 71% | “It was fun, because we came up with a fantasy story which i did not expect. Therefore this exercise helped me thinking outside the box.” “I usually write by myself, I don’t have 2 other brains with me. It’s incredible to have 2 [extra] creative brain.” “Really enjoyed coming up with ideas and building on the ideas of teammates. It made for coherent pieces that could surprise each other.” |

| Difficulties in the process | 11 respondents expressed that the creative process (setting the scene, creating the characters and the plot) was difficult sometimes. Several participants in the persona-focused workshops felt that the story creation exercise was rushed. | 13% | 33% | “I found it challenging to let the creative juices flow at first, but working with my colleagues definitely helped.” “Writing the [story] for some reason felt like cutting the story too short and that we lost the emotional momentum which was so powerful.” |

| Expressed Change or Intention of Change after Process | Summary of Change or Intention of Change | Number of Respondents Mentioning the Change | Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in Story-Focused Workshops | in Persona-Focused Workshops | |||

| Intention to use storytelling and personas in work practice | 23 respondents expressed the intention to use elements of storytelling and personas in their work, mostly to talk about their projects, to show different perspectives and the bigger picture, and to trigger an emotional response. | 60% | 24% | “It is a good teaching tool: it is good to learn how to communicate what you do but also to understand why you are building what you are building (like a chair). A better story and a better chair will come out.” “A good story takes us a long way in our sustainability efforts. When we’re able to engage stakeholder from an empathetic approach to our Environment we’ll be able to get their attention and make them feel the urge to act.” “After the workshop I have thought increasingly of characterization and personification of the abstract and inanimate as a powerful storytelling tool.” “I do think storytelling can have an impact even if you may not be aware of it at first. I liked learning how a story can draw empathy/attention and hearing different opinion. I want to address in my design brief that there isn’t one side to environmental change. And talk more about how it can change by communicating with the people and business.” |

| Increased awareness of environmental issues and consequences of actions | 16 respondents declared after the process made them more aware of the size of the issue and of the consequences of their actions on wildlife and nature. | 20% | 48% | “The story did motivate me more to be more aware of what is happening around me and try to understand the consequences of my actions. This is due to the fact that via the story, you can realize that your actions can have severe consequences even if those consequences are for someone […] who cannot talk in real life.” “It made me think about on-land problems and sea problems and it made me realize that environmental issues are huge and way bigger than anyone can even imagine, but we still have to act.” “You should really think twice before you do something, so you don’t hurt anyone else in the process.” |

| Intention to make changes in work practice to create more sustainable impact | 11 respondents want to have more sustainable focus and/or impact, for example by including systemic considerations, initiating dialogue or reflecting on the ethics of innovation in their projects and business transactions. | 20% | 24% | “I want to see people, profit and planet as equals and involve them all in my product design.” “I will prompt the question ‘what would the planet think about that?’ in future business cases.” “Thinking and feeling from the planets perspective as a tool in decision making is a huge AHA moment!” |

| Intention to consume more responsibly | 6 respondents expressed their intention to stop buying unnecessary items, to live with less, to be more informed of the origin of products, to use less plastic or more recycled products. | 17% | 5% | “The story made me become aware of what I need and what I don’t need. So that I can stop buying unnecessary purchases.” |

| No change | 11 respondents said they would not change anything after the process, mostly because they were already motivated to work on sustainability before. | 20% | 19% | “I already had the motivations to do something better for the environment.” “Can’t say that it changed anything. But I consider myself as someone who is already very aware about my values/behavior/prejudice—because of my work with design for sustainable behavior, so I don’t think I am the typical audience for such a workshop.” |

| No answer | 8 respondents do not know or did not answer the question. | 20% | 10% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talgorn, E.; Ullerup, H. Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’ through Participatory Ecological Storytelling: From Human-Centered to Planet-Centered Design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107794

Talgorn E, Ullerup H. Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’ through Participatory Ecological Storytelling: From Human-Centered to Planet-Centered Design. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107794

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalgorn, Elise, and Helle Ullerup. 2023. "Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’ through Participatory Ecological Storytelling: From Human-Centered to Planet-Centered Design" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107794

APA StyleTalgorn, E., & Ullerup, H. (2023). Invoking ‘Empathy for the Planet’ through Participatory Ecological Storytelling: From Human-Centered to Planet-Centered Design. Sustainability, 15(10), 7794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107794