Unleashing the Power of Connection: How Adolescents’ Prosocial Propensity Drives Ecological and Altruistic Behaviours

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Opening

1.2. Human and Ecological Domains of Prosocial Behaviour

1.3. Connection to Nature or People Is Needed to Prompt Action

1.4. Research Hypothesis and Goal

2. Method

2.1. Sample Population

2.2. Measures

- (1)

- There is currently no clear instrument to measure prosocial propensity. The study of [8] showed that the honesty-humility domain of the HEXACO personality inventory [39] indicates an individual’s prosocial propensity. Therefore, in this study, we chose to use honesty-humility as an indicator of prosocial propensity. We adapted the original HEXACO scale to behaviours specific to adolescents. Some items on the HEXACO honesty-humility scale for adolescents were also used [40] after optimizing their language fluency in Spanish. In addition, several new items were created (Appendix A Table A1, Supplementary Table S1).

- (2)

- The [41] scale was used to measure ecological behaviour. Some items on this scale were adapted to the Latin American context. We also created several new items (Appendix A Table A2, Supplementary Table S2).

- (3)

- The [42] scale was used to measure altruistic behaviour. The original scale was adapted to behaviours specific to adolescents and/or modified for Spanish (Appendix A Table A3, Supplementary Table S3).

- (4)

- Connection to people, connection to country, and connection to nature were measured using a modified version of [14]’s scale. We used the “People in my community” and “People in my country” response options from the original scale, while the third option (“People all over the world”) was excluded because we considered it too broad for the purposes of this study. As per [12], connection to nature was measured using an additional response option added to the measure (i.e., “Natural surroundings”). The predictive validity of this measure of connection to nature has been demonstrated by [12]. By assessing connection to nature with this type of measure, we were able to evaluate the connection to various domains using the same question stems, which allowed for better comparisons between them. Items on this scale were either identical to the original scale [14] or modified to optimize their fluency in Spanish (Appendix A Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6, Supplementary Tables S4–S6).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Population

3.2. Honesty-Humility as an Indicator

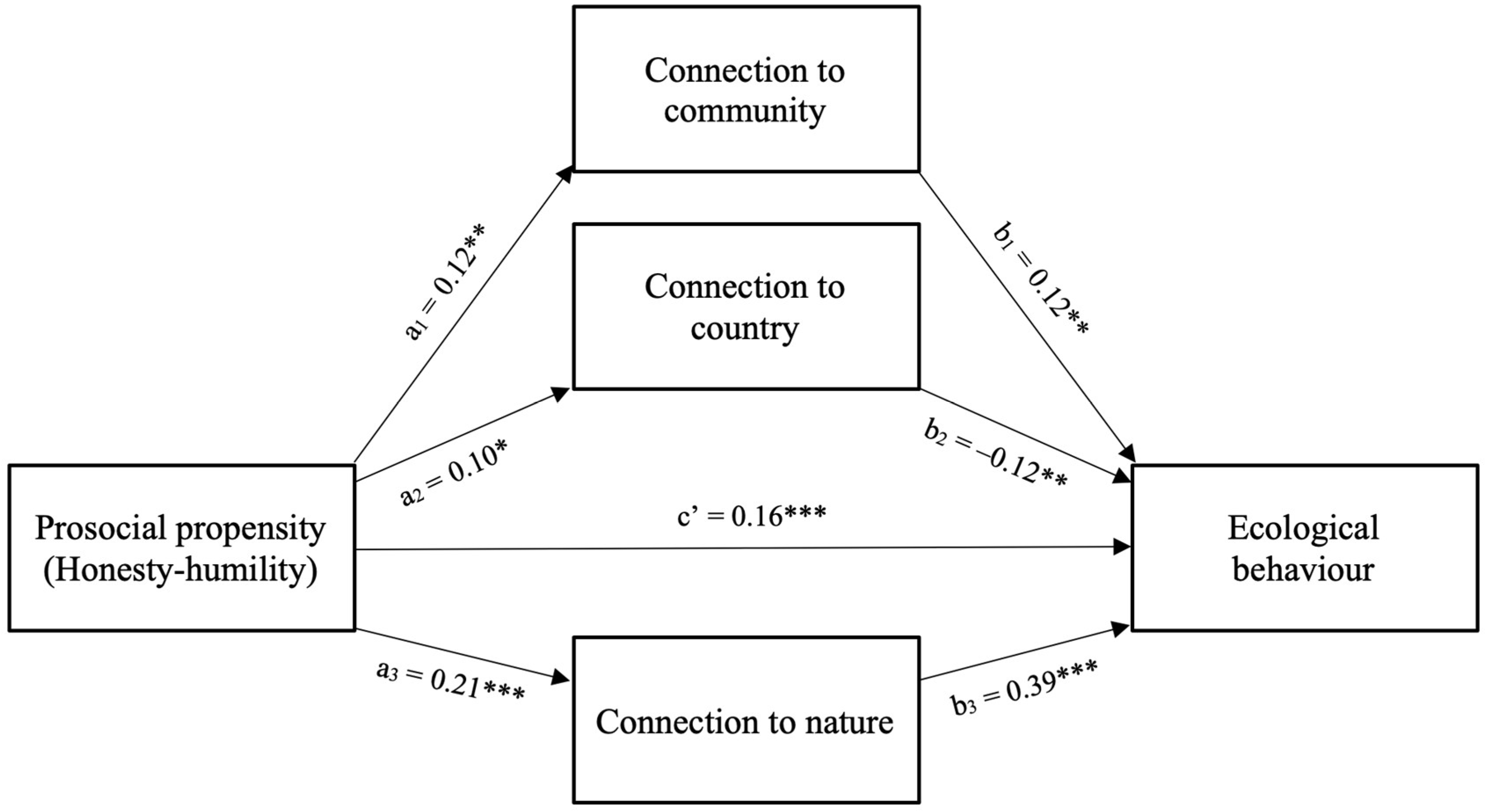

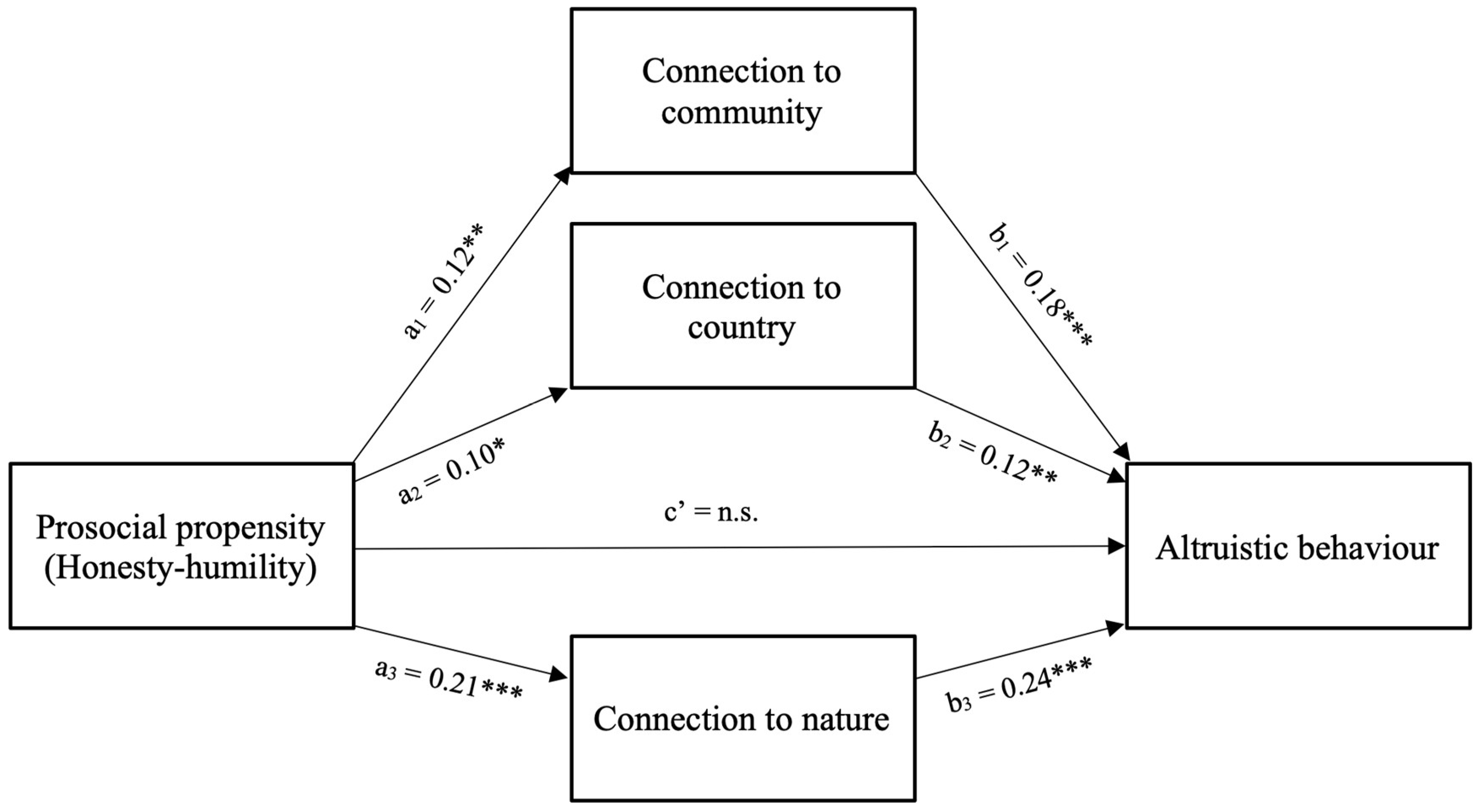

3.3. Mediation Effects

3.4. Possible Mechanisms

4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | People who get robbed are to blame for not properly guarding their property. | 0.54 | 1.47 |

| 4 | If I want something from a person I dislike, I will act very nicely toward that person in order to get it. | 0.45 | 1.14 |

| 16 | It is not a big deal to tell lies. | 0.32 | 0.92 |

| 7 | If I want something from someone, I will laugh at that person’s worst jokes. | 0.29 | 1.04 |

| 12 | I cheat if I am sure that I will not be discovered. | 0.24 | 0.98 |

| 14 | People should do what I say. | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| 20 | Verbal insults among teenagers are harmless. | 0.16 | 1.25 |

| 6 | I would compliment my teachers for better grades. | 0.11 | 1.20 |

| 5 | I consider myself superior to other people. | 0.07 | 1.00 |

| 13 | I want to have expensive and branded items (phone, clothes, etc.) to demonstrate my status. | −0.02 | 0.92 |

| 10 | I want people to know that I am an important person of high status. | −0.08 | 0.81 |

| 19 | Making fun of a person is not a big deal. | −0.22 | 0.99 |

| 9 | I’d be tempted to use counterfeit money, if I were sure I could get away with it. | −0.24 | 0.90 |

| 2 | I would be tempted to buy stolen property if I were financially tight. | −0.29 | 1.15 |

| 3 | I would like to find a way to take things from a store without paying. | −0.33 | 1.00 |

| 11 | Stealing a little bit of money is not a big deal. | −0.33 | 0.79 |

| 18 | Using someone else’s property without permission is just “borrowing”. | −0.42 | 0.76 |

| 15 | I want others to think that my family has money and high social status, even if it isn’t true. | −0.47 | 0.74 |

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | I have taken environmental classes to be more informed. | 2.13 | 1.01 |

| 32 | I refrain from battery-operated appliances. | 1.36 | 1.00 |

| 23 | I contribute financially to environmental organizations. | 1.12 | 0.96 |

| 26 | I talk to my friends about environmental issues. | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| 24 | I read books, publications, and other materials about environmental problems. | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| 30 | For printing, I use paper that was previously used on one side. | 0.71 | 0.99 |

| 16 | I separate organic waste and make compost. | 0.7 | 1.10 |

| 31 | For my parties I ask my parents not to use disposable plates and cutlery. | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| 6 | After one day of use, my sweaters or trousers go into the laundry. | 0.50 | 1.43 |

| 37 | When I shower, I turn off the water while I soap up and then turn on the water again to rinse, so that I don’t have it running all the time. | 0.44 | 0.96 |

| 40 | If there is a relatively large insect in my house, I carefully catch it and release it outside. | 0.43 | 0.90 |

| 14 | I collect and recycle used paper. | 0.39 | 0.92 |

| 22 | I have pointed out unecological behaviour to someone. | 0.33 | 0.91 |

| 27 | I watch TV shows or Internet videos about nature. | 0.33 | 0.86 |

| 15 | I bring empty glass bottles to a recycling bin. | 0.31 | 1.01 |

| 8 | I leave electrically powered appliances (TV, stereo, printer) on standby when they’re not in use. | 0.23 | 1.13 |

| 43 | I learn about environmental issues in the media (newspapers, magazines, and TV). | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| 17 | I keep gift wrapping paper for reuse. | 0.03 | 0.97 |

| 19 | I kill insects with a chemical insecticide. | 0.01 | 1.35 |

| 9 | In the winter, I turn down the heat when I leave my room for more than one hour. | −0.04 | 1.14 |

| 13 | I put empty batteries in the garbage. | −0.09 | 1.37 |

| 20 | I eat in fast-food restaurants, such as McDonalds and Burger King. | −0.09 | 1.01 |

| 28 | I recycle or reuse plastic containers. | −0.17 | 0.79 |

| 41 | For short distances I walk or ride a bike. | −0.23 | 0.93 |

| 18 | For making notes, I take paper that is already used on one side. | −0.23 | 0.90 |

| 12 | I use and refill a reusable bottle. | −0.26 | 0.97 |

| 11 | I buy beverages in cans. | −0.33 | 1.19 |

| 38 | I encourage my family and/or friends to be more environmentally friendly. | −0.57 | 0.89 |

| 10 | I choose to cycle when I need to go somewhere. | −0.58 | 0.98 |

| 25 | When I brush my teeth, I leave the water running until I finish. | −0.73 | 1.17 |

| 21 | I reuse my shopping bags. | −0.76 | 0.96 |

| 7 | As the last person to leave a room, I switch off the lights. | −0.84 | 1.06 |

| 29 | I turn off TV, computer and other electrical appliances when they are not in use. | −0.87 | 0.97 |

| 42 | I prefer natural and/or eco-labelled products. | −0.94 | 0.89 |

| 33 | I prefer products in biodegradable packaging. | −1.11 | 0.90 |

| 34 | After a picnic, I leave the place as clean as it was before. | −3.68 | 0.95 |

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | I have done volunteer work for a charity. | 0.95 | 1.08 |

| 12 | I would offer comfort to a crying stranger. | 0.64 | 0.98 |

| 2 | I have given money to a charity. | 0.54 | 1.01 |

| 19 | I offer help when I hear people discuss subjects I am familiar with. | 0.36 | 1.00 |

| 16 | I would help search for a lost pet even if the owner is unfamiliar to me. | 0.36 | 0.92 |

| 5 | I have helped carry a stranger’s belongings (books, parcels, etc.). | 0.32 | 0.84 |

| 7 | I have allowed someone to go ahead of me in a queue (as in giving up my place in line for someone, etc.). | 0.19 | 0.91 |

| 8 | I buy products connected with the Telethon. | 0.09 | 1.27 |

| 18 | If I find myself at the door at the same time with another person, I let them go first. | 0.07 | 0.98 |

| 6 | I have delayed an elevator and held the door open for a stranger. | −0.07 | 0.96 |

| 3 | I have donated goods or clothes to a charity. | −0.14 | 0.95 |

| 14 | When an unfamiliar person asks me something, I ignore them. | −0.21 | 1.49 |

| 11 | I have offered my seat on a bus or train to a stranger who was standing. | −0.24 | 0.93 |

| 10 | I have offered to help a handicapped or elderly stranger across a street. | −0.29 | 0.77 |

| 13 | I would help a stranger who fell on the street. | −0.37 | 0.74 |

| 1 | I have given directions to a stranger. | −0.55 | 0.91 |

| 17 | If a stranger asks me for the time, I promptly tell them. | −0.80 | 1.02 |

| 9 | I ignore strangers who ask me to help read something for them. | −0.85 | 1.51 |

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | To what degree do you think of the following groups of people as “family”? | 0.23 | 1.02 |

| 3 | How much would you say you have in common with the following groups? | 0.35 | 1.16 |

| 2 | How often do you use the word “we” to refer to the following groups of people? | 0.67 | 0.92 |

| 1 | How close do you feel to each of the following groups? | 0.89 | 1.06 |

| 5 | How much do you care about each of the following groups? | −0.11 | 0.71 |

| 7 | How much do you want to be …?: | −0.36 | 0.93 |

| 8 | How much do you believe in …?: | −0.31 | 1.07 |

| 6 | How much would you say you care (feel upset, want to help) when bad things happen to the following groups? | −0.33 | 1.04 |

| 9 | If the need arises, how willing are you to help the following groups? | −1.05 | 1.01 |

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | To what degree do you think of the following groups of people as “family”? | 0.69 | 1.1 |

| 3 | How much would you say you have in common with the following groups? | 0.08 | 1.18 |

| 2 | How often do you use the word “we” to refer to the following groups of people? | 0.44 | 0.9 |

| 1 | How close do you feel to each of the following groups? | 1.42 | 1.1 |

| 5 | How much do you care about each of the following groups? | −0.01 | 0.79 |

| 7 | How much do you want to be …?: | −0.64 | 0.97 |

| 8 | How much do you believe in …?: | −0.44 | 0.97 |

| 6 | How much would you say you care (feel upset, want to help) when bad things happen to the following groups? | −0.63 | 1.03 |

| 9 | If the need arises, how willing are you to help the following groups? | −0.91 | 0.88 |

| Nº | Item | Delta | MS Infit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | To what degree do you think of the following groups of people as “family”? | 0.13 | 1.03 |

| 3 | How much would you say you have in common with the following groups? | 0.69 | 1.41 |

| 2 | How often do you use the word “we” to refer to the following groups of people? | 0.72 | 0.94 |

| 1 | How close do you feel to each of the following groups? | 0.97 | 1.23 |

| 5 | How much do you care about each of the following groups? | −0.25 | 0.79 |

| 7 | How much do you want to be …?: | −0.28 | 0.98 |

| 8 | How much do you believe in …?: | −0.32 | 0.82 |

| 6 | How much would you say you care (feel upset, want to help) when bad things happen to the following groups? | −0.8 | 0.89 |

| 9 | If the need arises, how willing are you to help the following groups? | −0.86 | 0.92 |

References

- Eisenberg, N.; Shell, R. Prosocial Moral Judgment and Behavior in Children: The Mediating Role of Cost. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 12, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; VanSchyndel, S.K.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial Motivation: Inferences From an Opaque Body of Work. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D.; Powell, A.A. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In Handbook of Psychology; McGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield, K.A. A construct divided: Prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, T.; Otto, S. Explaining the difference between the predictive power of value orientations and self-determined motivation for proenvironmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 4, 49-CP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Otto, S.; Schuler, J. Prosocial propensity bias in experimental research on helping behavior: The proposition of a discomforting hypothesis. Compr. Psychol. 2015, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Byrka, K. Environmentalism as a trait: Gauging people’s prosocial personality in terms of environmental engagement. Int. J. Phychol. 2011, 46, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P.; Zabel, S.; Diaz-Siefer, P.; Burnham, E.; Navarro-Villarroel, C.; Neaman, A. The prosocial origin of sustainable behavior: A case study in the ecological domain. Glob. Environ. Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2021, 69, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A.; Otto, S.; Vinokur, E. Toward an integrated approach to environmental and prosocial education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A.; Pensini, P.; Zabel, S.; Otto, S.; Ermakov, D.S.; Dovletyarova, E.A.; Burnham, E.; Castro, M.; Navarro-Villarroel, C. The Prosocial Driver of Ecological Behavior: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Prosocial and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldy, S.P.; Piff, P.K. Toward a social ecology of prosociality: Why, when, and where nature enhances social connection. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, S.; Webb, M.; Brown, D. All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.L.; Hall, B.J.; Chen, H. Sense of community responsibility and altruistic behavior in Chinese community residents: The mediating role of community identity. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 1999–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Price, J.; Leviston, Z. My country or my planet? Exploring the influence of multiple place attachments and ideological beliefs upon climate change attitudes and opinions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 30, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renger, D.; Reese, G. From equality-based respect to environmental activism: Antecedents and consequences of global identity. Political Psychol. 2017, 38, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B.; Buchan, N.R.; Ozturk, O.D.; Grimalda, G. Parochial Altruism and Political Ideology. Political Psychol. 2022, 44, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnysh, V.; Lucas, C.; Singh, P. The Ties That Bind: National Identity Salience and Pro-Social Behavior Toward the Ethnic Other. Comp. Political Stud. 2015, 48, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Osborne, D.; Yogeeswaran, K.; Sibley, C.G. The role of national identity in collective pro-environmental action. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislak, A.; Wojcik, A.D.; Cichocka, A. Cutting the forest down to save your face: Narcissistic national identification predicts support for anti-conservation policies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislak, A.; Cichocka, A.; Wojcik, A.D.; Milfont, T.L. Words not deeds: National narcissism, national identification, and support for greenwashing versus genuine proenvironmental campaigns. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlicht-Schmalzle, R.; Chykina, V.; Schmalzle, R. An attitude network analysis of post-national citizenship identities. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, E.; Bagci, S.C.; Kelesoglu, I. Love for the globe but also the country matter for the environment: Links between nationalistic, patriotic, global identification and pro-environmentalism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C.; Choi, J.; Zachariassen, K. Connectedness to Nature and to Humanity: Their association and personality correlates. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durón-Ramos, M.F.; Collado, S.; García-Vázquez, F.I.; Bello-Echeverria, M. The Role of Urban/Rural Environments on Mexican Children’s Connection to Nature and Pro-environmental Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Corraliza, J.A.; Staats, H.; Ruiz, M. Effect of frequency and mode of contact with nature on children’s self-reported ecological behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Evans, G.W. Outcome expectancy: A key factor to understanding childhood exposure to nature and children’s pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiya, S.; Carlo, G.; Gulseven, Z.; Crockett, L. Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement, deviant peer affiliation, and school connectedness on prosocial behaviors in US Latino/a youth. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 2898–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Feng, X.; Day, R.D. Adolescents’ Empathy and Prosocial Behavior in the Family Context: A Longitudinal Study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1858–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Hernández, L.F.; Sotelo-Castillo, M.A.; Echeverría-Castro, S.B.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.O. Connectedness to Nature: Its Impact on Sustainable Behaviors and Happiness in Children. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensini, P.; Horn, E.; Caltabiano, N.J. An exploration of the relationships between adults’ childhood and current nature exposure and their mental well-being. Child. Youth Environ. 2016, 26, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I.; Astell-Burt, T.; Cliff, D.P.; Vella, S.A.; John, E.E.; Feng, X.Q. The Relationship Between Green Space and Prosocial Behaviour Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. MedPower: An Interactive Tool for the Estimation of Power in Tests of Mediation. Available online: https://davidakenny.shinyapps.io/MedPower/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychometric Properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 2018, 25, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, I.; Gnisci, A.; Senese, V.P.; Perugini, M. The HEXACO-Middle School Inventory (MSI) A Personality Inventory for Children and Adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2020, 36, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Oerke, B.; Bogner, F.W. Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, J.P.; Chrisjohn, R.D.; Fekken, G.C. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1981, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. A User’s Guide to WINSTEPS Rasch-Model Computer Programs; MESA Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog, K.G.; Sorbom, D. LISREL 8 User’s Guide; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.D.; Linacre, J.M.; Gustafson, J.E.; Martin-Lof, P. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 8, 370–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Empirical, Theoretical, and Practical Advantages of the HEXACO Model of Personality Structure. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brick, C.; Lewis, G.J. Unearthing the “Green” Personality: Core Traits Predict Environmentally Friendly Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2014, 48, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Böhm, R. Honesty-humility under threat: Self-uncertainty destroys trust among the nice guys. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward A Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, N.; Mohammadtabar, S.; Saffarinia, M. Dirty Dozen vs. the H factor: Comparison of the Dark Triad and Honesty-Humility in prosociality, religiosity, and happiness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 67, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, I.; Hilbig, B.E.; Haubrich, J. Altruism at the ballots: Predicting political attitudes and behavior. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, B.E.; Zettler, I.; Moshagen, M.; Heydasch, T. Tracing the Path from Personality—Via Cooperativeness—To Conservation. Eur. J. Personal. 2013, 27, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Fang, L. Honesty-humility and prosocial behavior: The mediating roles of perspective taking and guilt-proneness. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 60, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertag, A.; Bratko, D. In search of the prosocial personality: Personality traits as predictors of prosociality and prosocial behavior. J. Individ. Differ. 2019, 40, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, I.; Hilbig, B.E. Honesty and humility. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Soutter, A.; Bates, T.; Mottus, R. Big Five and HEXACO Personality Traits, pro-environmentalattitudes, and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 69, 102312. [Google Scholar]

- Angelis, S.; Pensini, P. Honesty-Humility Predicts Humanitarian Prosocial Behaviour via Social Connectedness: A Parallel Mediation Examining Connectedness to Community, Nation, Humanity, and Nature. Scand. J. Psychol. 2023, 209, 112216. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, M.; Pensini, P. The Role of Connectedness in Sustainable Behaviour: A Parallel Mediation Model Examining the Prosocial Foundations of Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 209, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Andaur, A. Integrating prosocial and proenvironmental behaviors: The role of moral disengagement and peer social norms. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2022, 14, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Durón-Ramos, M.F. Assessing sustainable behavior and its correlates: A measure of pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic and equitable actions. Sustainability 2013, 5, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazono, K.; Inarimori, K. Empathy, Altruism, and Group Identification. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, C.A.; Byington, R.; Gallay, E.; Sambo, A. Social Justice and the Environmental Commons. In Equity and Justice in Developmental Science: Implications for Young People, Families, and Communities; Horn, S.S., Ruck, M.D., Liben, L.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 51, pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L.K. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, I.; Williams, D.; Hwang, F.; Kirke, A.; Miranda, E.R.; Nasuto, S.J. Electroencephalography reflects the activity of sub-cortical brain regions during approach-withdrawal behaviour while listening to music. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean ± standard deviation (years) | 15 ± 2.0 |

| Range (years) | 11–19 |

| Gender | |

| Female (%) | 51 |

| Male (%) | 48 |

| Prefer not to specify (%) | 1 |

| Family income | |

| We are perfectly comfortable with our income (%) | 0 |

| Our income is quite sufficient (%) | 51 |

| We can manage on our income (%) | 42 |

| It is pretty difficult to live on our income (%) | 7 |

| It is extremely tough to live on our income (%) | 0 |

| Area of residence | |

| Countryside (%) | 24 |

| City (%) | 76 |

| Nationality | |

| Chile (%) | 69 |

| Spain (%) | 21 |

| Mexico (%) | 4 |

| Guatemala (%) | 2 |

| Other nationalities (<1% each) (%) | 3 |

| Scale | Number of Items | Mean ± SD | Range | Reliability | Items with 1.2 < MS ≤ 1.3 | Items with MS > 1.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honesty-humility | 18 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | −1.7–4.4 | 0.73 | 1 | 1 |

| Connection to community | 9 | 0.31 ± 1.7 | −5.3–5.4 | 0.88 | 0 | 0 |

| Connection to country | 9 | −0.21 ± 1.4 | −5.3–5.4 | 0.83 | 0 | 0 |

| Connection to nature | 9 | 0.68 ± 1.6 | −5.1–5.4 | 0.84 | 0 | 0 |

| Ecological behaviour | 36 | 0.28 ± 0.50 | −2.3–1.6 | 0.83 | 0 | 3 |

| Altruistic behaviour | 18 | 0.17 ± 0.68 | −2.4–2.4 | 0.84 | 1 | 2 |

| Sustainable behaviour | 54 | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 0.81–1.4 | 0.88 | 6 | 4 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Honesty-humility | |||||

| 2. Connection to community | 0.12 * | ||||

| 3. Connection to country | 0.10 * | 0.64 ** | |||

| 4. Connection to nature | 0.21 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.41 ** | ||

| 5. Altruism | 0.11 * | 0.35 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.36 ** | |

| 6. Ecological behaviour | 0.25 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.54 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neaman, A.; Montero, E.; Pensini, P.; Burnham, E.; Castro, M.; Ermakov, D.S.; Navarro-Villarroel, C. Unleashing the Power of Connection: How Adolescents’ Prosocial Propensity Drives Ecological and Altruistic Behaviours. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108070

Neaman A, Montero E, Pensini P, Burnham E, Castro M, Ermakov DS, Navarro-Villarroel C. Unleashing the Power of Connection: How Adolescents’ Prosocial Propensity Drives Ecological and Altruistic Behaviours. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108070

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeaman, Alexander, Eiliana Montero, Pamela Pensini, Elliot Burnham, Mónica Castro, Dmitry S. Ermakov, and Claudia Navarro-Villarroel. 2023. "Unleashing the Power of Connection: How Adolescents’ Prosocial Propensity Drives Ecological and Altruistic Behaviours" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108070