The Sustainable Business Model Database: 92 Patterns That Enable Sustainability in Business Model Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Definition of Core Constructs

2.1. Business Model

2.2. Business Model Innovations

2.3. Sustainable Business Model Innovation

2.4. Business Model Patterns and Sustainable Business Model Patterns

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Literature Review on the Topic of Sustainable Business Model Patterns

3.2. Creation of a Taxonaomy

- Object of Analysis: All company types are valid.

- Data Collection: Systematic Literature Review

- Data Sampling: Selective/Comprehensive

- Development: The approach of Nickerson, Varshney, Muntermann [94] was used as it enables deep insights into the topic and also provides a practical results.

- Industry Scope: Generic

- Technology Scope: Generic but focus on sustainability

- Depth of Analysis: Wide

- Representation: Exclusivity

- Visualisation: Table

- Further Application: (Arche-)Types

- Clustering Tool: Outcome proximity

3.3. Creation of the Database through Classification of the Patterns

4. Results

5. Discussion & Limitations

6. Direction for Future Studies & Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Source | Source | Name of the Publication |

|---|---|---|

| [88] | International Journal of Innovation Management | The Business Model Pattern Database—A Tool For Systematic Business Model Innovation |

| [105] | Journal of Industrial Ecology | A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns |

| [106] | OECD Publishing | Why New Business Models Matter for Green Growth |

| [107] | Nordic Innovation | Green Business Model Innovation |

| [32] | SustainAbility Inc | 20 Business Model Innovations for Sustainability |

| [108] | Journal of Cleaner Production | Analysis of the growth of the e-learning industry through sustainable business model archetypes: A case study |

| [26] | International Journal of Innovation Management | Business model innovations for electric mobility what can be learned from existing business |

| [31] | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable business model adoption among S&P 500 firms: A longitudinal content analysis study |

| [33] | Journal of Cleaner Production | Business model patterns of sustainability pioneers—Analyzing cases across the smartphone life cycle |

| [87] | Journal of Cleaner Production | Business model patterns in the sharing economy |

| [109] | Nordic Council of Ministers | Moving towards a circular economy |

| [110] | Entrepreneurship Research Journal | Monetizing Social Value Creation–A Business Model Approach |

| [111] | International Finance Corporation | Accelerating Inclusive Business Opportunities: Business Models that Make a Difference |

| [20] | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sustainable business model innovation: A review |

| [112] | Sustainable Production and Consumption | Circular business models for the fastmoving consumer goods industry: Desirability, feasibility, and viability |

| [113] | Sustainability | Characterisation and Environmental Value Proposition of Reuse Models for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods: Reusable Packaging and Products |

| [114] | IS4CE 2020 Conference of the International Society for the Circular Economy | The Evolution of Reuse and Recycling Behaviours |

References

- Rashid, A.; Asif, F.M.; Krajnik, P.; Nicolescu, C.M. Resource Conservative Manufacturing: An essential change in business and technology paradigm for sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csik, M. Muster und das Generieren von Ideen für Geschäftsmodellinnovationen. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchikhi, H.; Kimberly, J. Escaping the Identity Trap. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J. Business model dynamics and innovation: (Re)establishing the missing linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Spring, M. The sites and practices of business models. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Rindova, V.P.; Greenbaum, B.E. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Concepts: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.; Dos Santos, B.; Zheng, Z. Digital Innovation as a Fundamental and Powerful Concept in the Information Systems Curriculum. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2014, 38, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R. Integrating Product and Service Innovation. Res. Technol. Manag. 2009, 52, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Voss, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. Modes of service innovation: A typology. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 1358–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, A.; Zott, C. Creating Value Through Business Model Innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.W.; Lafley, A.G. Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Matzler, K.; Bailom, F.; Friedrich von den Eichen, S. Geschäftsmodellinnovationen. In Unternehmensführung: State of the Art und Entwicklungsperspektiven; [die Herausgeberinnen nehmen nun den 65. Geburtstag von Richard Hammer zum Anlass, mit dieser Festschrift ihre Wertschätzung gegenüber dem Jubilar zum Ausdruck zu bringen]; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, W.J.; Fonseca, A.; Morioka, S.N. Strategic sustainability integration: Merging management tools to support business model decisions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2052–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Success factors for environmentally sustainable product innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, H.; Jørgensen, S.; Pedersen, L.J.T.; Skard, S. Experimenting with sustainable business models in fast moving consumer goods. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 270, 122302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Designing Business Models and Similar Strategic Objects: The Contribution of IS. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 14, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Spieth, P. Business Model Innovation: Torwards an integrated future reseach agenda. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit, D.; Clemons, E.; Benlian, A.; Buxmann, P.; Hess, T.; Kundisch, D.; Spann, M. Business Models. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosna, M.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R.N.; Velamuri, S.R. Business Model Innovation through Trial-and-Error Learning. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausemeier, J.; Wieseke, J.; Echterhoff, B.; Koldewey, C.; Mittag, T.; Schneider, M.; Isenberg, L. Mit Industrie 4.0 zum Unternehmenserfolg: Integrative Planung von Geschäftsmodellen und Wertschöpfungssystemen; Heinz Nixdorf Institut, Universität Paderborn: Paderborn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkafi, N.; Makhotin, S.; Posselt, T. Business model innovations for electric mobility: What can be learned from existing business. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Morgan, M.S. Business Models as Models. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganova, L.; Eyquem-Renault, M. What do business models do? Res. Policy 2009, 38, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weking, J.; Hein, A.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. A hierarchical taxonomy of business model patterns. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, L.C.; Aguiar, C.C.; Sehnem, S.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Cazella, C.F.; Julkovski, D.J. Sustainable business models: A literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 2028–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P.; Huotari, P.; Bocken, N.; Albareda, L.; Puumalainen, K. Sustainable business model adoption among S&P 500 firms: A longitudinal content analysis study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, L.; Whisnant, R. Model Behavior: 20 Business Model Innovations for Sustainability; Sustain Ability Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zufall, J.; Norris, S.; Schaltegger, S.; Revellio, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business model patterns of sustainability pioneers—Analyzing cases across the smartphone life cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseletto, P. Targets for a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labes, S.; Hahn, C.; Erek, K.; Zarnekow, R. Geschäftsmodelle im Cloud Computing. In Digitalisierung und Innovation; Keuper, F., Hamidian, K., Verwaayen, E., Kalinowski, T., Kraijo, C., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Clark, T. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. From Strategy to Business Models and onto Tactics. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C.C. Game-Changing Strategies: How to Create New Market Space in Established Industries by Breaking the Rules, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. Available online: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0827/2008009622-d.html (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Bellman, R.; Clark, C.E.; Malcolm, D.G.; Craft, C.J.; Ricciardi, F.M. On the Construction of a Multi-Stage, Multi-Person Business Game. Oper. Res. 1957, 5, 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziani, A.; Ventresca, M.J. Keywords and Cultural Change: Frame Analysis of Business Model Public Talk, 1975–2000. Sociol. Forum 2005, 20, 523–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSilva, C.M.; Trkman, P. Business Model: What It Is and What It Is Not. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O.; Frankenberger, K.; Sauer, R. Exploring the Field of Business Model Innovation: New Theoretical Perspectives; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmers, P. Business Models for Electronic Markets. Electron. Mark. 1998, 8, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, A.; Zott, C. Value creation in E-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.W.; Zhao, Q. Internet Marketing, Business Models, and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C. Amit Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.L.; Afuah, A. A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Change 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magretta, J. Why Business Models Matter. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Christensen, C.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.; Schindehutte, M.; Allen, J. The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Internet Business Models and Strategies: Text and Cases; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G. Leading the Revolution; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.C.; Mauborgne, R. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, expanded ed.; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matthyssens, P.; Vandenbempt, K.; Berghman, L. Value innovation in business markets: Breaking the industry recipe. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.C.; Davidson, R.A. Applications of the business model in studies of enterprise success, innovation and classification: An analysis of empirical research from 1996 to 2010. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecocq, X.; Demil, B.; Ventura, J. Business Models as a Research Program in Strategic Management: An Appraisal based on Lakatos. M@N@Gement 2010, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. Disruptive Innovation: In Need of Better Theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comes, S.; Berniker, L. Business Model Innovation. In From Strategy to Execution: Turning Accelerated Global Change Into Opportunity; Pantaleo, D.C., Pal, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.H.; Zott, C. Business Model Innovation: Creating Value in Times of Change. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 23, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, S. Business Model Innovation How Incumbent Organizations Adopt Dual Business Models. Ph. D. Thesis, Universität St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzeland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.M.; Clark, K.B. Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollenkop, M. Geschäftsmodellinnovation: Initiierung Eines Systematischen Innovationsmanagements für Geschäftsmodelle auf Basis Lebenszyklusorientierter Frühaufklärung. Zugl.: Bamberg, Univ., Diss., 2006 (1. Aufl.). Gabler Edition Wissenschaft Schriften zum Europäischen Management. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden. Available online: http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=752400 (accessed on 20 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, J.; Mardani, A.; Chofreh, A.G.; Goni, F.A.; Klemeš, J.J. Anatomy of sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Shared Value: Die Brücke von Corporate Social Responsibility zu Corporate Strategy. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Schneider, A., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Sharing economy: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Wijsman, K. Business transition management: Exploring a new role for business in sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Louche, C. Journeying toward Business Models for Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, Y.; Nielsen, C.; Montemari, M.; Thomsen, P.; Paolone, F. Business model configurations: A five-V framework to map out potential innovation routes. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 19, 492–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O.; Frankenberger, K.; Csik, M. Geschäftsmodelle Entwickeln: 55 innovative Konzepte mit dem St. Galler Business Model Generator 2., überarbeite und erweiterte Auflage; Hanser: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Girotra, K.; Netessine, S. OM Forum—Business Model Innovation for Sustainability. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, J.O. A pattern approach to interaction design. AI Soc. 2001, 15, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, P.; Vitale, M. Place to Space: Migration to Ebusiness Models; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amshoff, B.; Dülme, C.; Echterfeld, J.; Gausemeier, J. Business model patterns for disruptive technologies. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 19, 1540002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echterfeld, J.; Amshoff, B.; Gausemeier, J. How to use Business Model Pattern for exploiting disruptive Technologies. In Technology, Innovation and Management for Sustainable Growth, Proceedings of the 24th International Conference of the International Association for Management of Technology (IAMOT 2015), Cape Town, South Africa, 8–11 June 2015; Pretorius, L., Thopil, G.A., Eds.; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2294–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth, A. Geschäftsmodellinnovation: Theorie und Praxis der Erfolgreichen Realisierung von Strategischen Innovationen in Großunternehmen. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weltgen, M. Systematische und Institutionalisierte Geschäftsmodellinnovation: Eine Explorative Studie in deutschen Konzernen. Schriften zur Unternehmensentwicklung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polos, L.; Hannan, M.; Carroll, G. Foundations of a Theory of Social Forms. Ind. Corp. Change 2002, 11, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Bock, A.J. The Business Model in Practice and its Implications for Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.K. Business model patterns in the sharing economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1650–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remane, G.; Hanelt, A.; Tesch, J.; Kolbe, L. The Business Model Pattern Database: A Tool For Systematic Business Model Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Carroux, S.; Joyce, A.; Massa, L.; Breuer, H. The sustainable business model pattern taxonomy—45 patterns to support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Thorpe, R.; Jackson, P.R. Management and Business Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publ.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dahdul, W.; Manda, P.; Cui, H.; Balhoff, J.P.; Dececchi, T.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Lapp, H.; Vision, T.; Mabee, P.M. Annotation of phenotypes using ontologies: A gold standard for the training and evaluation of natural language processing systems. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2018, 2018, bay110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Johnson, E.J.; Herrmann, A. Individual-level loss aversion in riskless and risky choices. Theory Decis. 2022, 92, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, J.; Cantrell, S. Changing Business Models: Surveying the Landscape; Accenture Institute for Strategic Change: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, R.C.; Varshney, U.; Muntermann, J. A method for taxonomy development and its application in information systems. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S.; Hevner, A.R. Positioning and Presenting Design Science Research for Maximum Impact. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S. The Importance of Classification to Business Model Research. J. Bus. Model. 2015, 3, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, F.; Stachon, M.; Azkan, C.; Schoormann, T.; Otto, B. Designing business model taxonomies—Synthesis and guidance from information systems research. Electron. Mark. 2021, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Business Intelligence Aspect for Emotions and Sentiments Analysis. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT), Tamil Nadu, India, 5–7 April 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Data Visualization to Explore the Countries Dataset for Pattern Creation. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2021, 17, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMobark, B.A.A. A Quantitative Approach for Data Visualization in Human Resource Management. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2023, 22, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Broccardo, L.; Zicari, A. Sustainability as a driver for value creation: A business model analysis of small and medium entreprises in the Italian wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sawy, O.A.; Pereira, F. Business Modelling in the Dynamic Digital Space; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuver, M.; de Bouwman, H.; Haaker, T. Business model roadmapping: A practical approach to come from an existing to a desired business model. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Froese, T.; Schaltegger, S. The role of business models for sustainable consumption: A pattern approach. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Mont, O., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramello, A.; Haie-Fayle, L.; Pilat, D. Why New Business Models Matter for Green Growth; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, K.; Bjerre, M.; Øster, J.; Bisgaard, T. Green Business Model Innovation; Nordic Innovation: Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, N.; Villarreal, Ó. Analysis of the growth of the e-learning industry through sustainable business model archetypes: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiørboe, N.; Sramkova, H.; Krarup, M. Moving towards a Circular Economy; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, S.; Raith, M.; Siebold, N. Monetizing Social Value Creation—A Business Model Approach. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, B.; Ishikawa, E.; Geaneotes, A.; Baptista, P.; Masuoka, T. Accelerating Inclusive Business Opportunities: Business Models That Make a Difference; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.; Harsch, A.; Weissbrod, I. Circular business models for the fastmoving consumer goods industry: Desirability, feasibility, and viability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranko, Ż.; Tassell, C.; van der Zeeuw Laan, A.; Aurisicchio, M. Characterisation and Environmental Value Proposition of Reuse Models for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods: Reusable Packaging and Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassell, C.; Aurisicchio, M. The Evolution of Reuse and Recycling Behaviours: An Integrative Review with Application to the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods Industry. In Proceedings of the Conference of the International Society for the Circular Economy, online, 17 October 2022; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/43323870/The_Evolution_of_Reuse_and_Recycling_Behaviours_An_Integrative_Review_with_Application_to_the_Fast_Moving_Consumer_Goods_Industry (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Seidenstricker, S.; Linder, C. A morphological analysis-based creativity approach to identify and develop ideas for BMI: A case study of a high-tech manufacturing company. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2014, 18, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Tilly, R.; Bodenbenner, P.; Seltitz, A.; Schoder, D. (Eds.) Geschäftsmodellinnovation in der Praxis: Ergebnisse einer Expertenbefragung zu Business Model Canvas und Co. Wirtsch. Proc. 2015, 2015, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slávik, Š.; Bednár, R.; Mišúnová Hudáková, I. The Structure of the Start-Up Business Model—Qualitative Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia-Bauer, C.; Vondung, F.; Thomas, S.; Moser, R. Business Model Innovations for Renewable Energy Prosumer Development in Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, E. Hybrid business models in the sharing economy: The role of business model design for managing the environmental paradox. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amshoff, B. Systematik zur Musterbasierten Entwicklung Technologie-Induzierter Geschäftsmodelle. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Paderborn, Paderborn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charnley, F.; Knecht, F.; Muenkel, H.; Pletosu, D.; Rickard, V.; Sambonet, C.; Schneider, M.; Zhang, C. Can Digital Technologies Increase Consumer Acceptance of Circular Business Models? The Case of Second Hand Fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. Circular business model implementation: A capability development case study from the manufacturing industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Definition | Source |

|---|---|

| “(…) an architecture of the product, service and information flows, including a description of the various business actors and their roles; a description of the potential benefits for the various business actors; a description of the sources of revenues.” | [43] |

| “(…) how a firm will make money” | [44] |

| “A business model depicts the content, structure and governance of transactions designed so as to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities.” | [45] |

| “(…) a system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries.” | [46] |

| “A business model is (…) a reflection of the firm’s realized strategy” | [37] |

| “A business model articulates the logic, the data and other evidence that support a value proposition for the customer, and a viable structure of revenues and costs for the enterprise delivering that value.” | [47] |

| “(…) a description of an organization and how that organization functions in achieving its goals (e.g., profitability, growth, social impact, (…)” | [48] |

| Period | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1975–1994 | computer/systems modelling (technology model) |

| 1995–2000 | value creation (unit model) |

| 2001–today | revenue model als Summe von value creation und value capture (Komponentenmodell) |

| Definition | Source |

|---|---|

| “Business Model-Innovation is (…) how a firm will make money” | [44] |

| “Businessmodel innovation is the discovery of a fundamentally different business model in an existing business.” | [59] |

| “Business model innovation is the convergence of both a new profit model and a new customer value proposition, unified to create an entirely new type of market player.” | [60] |

| “Business Model-Innovation is (…) unit of analysis, [to] identify novelty, lock-in complementarities and efficiency.” | [61] |

| “Business Model Innovation (…) represents an (…) source of future value for businesses—a way of creating new or enhanced revenues and profits at relatively low cost” | [62] |

| “Business model innovation is about generating new sources of profit by finding novel value proposition/value constellation combinations.” | [63] |

| “Business model innovation refers to a business model configuration that specifies new ways to create and capture value for the focal organization, its customers, and other stakeholders.” | [64] |

| Definition | Source |

|---|---|

| “Sustainable business model innovation is understood as the adaption of the business model to overcome barriers within the company and its environment to market sustainable process, product, or service innovations.” | [18] |

| “(…) searching for ways to deal with unpredictable (…) wider societal changes and sustainability issues.” | [70] |

| “Business model innovations for sustainability are defined as: Innovations that create significant positive and/or significantly reduced negative impacts for the environment and/or society, through changes in the way the organization and its value-network create, deliver value and capture value (i.e., create economic value) or change their value propositions.” | [71] |

| “Sustainable business innovation processes specifically aim at incorporating sustainable value and a pro-active management of a broad range of stakeholders into the business model.” | [72] |

| “(…) processes through which (…) new business models are developed by businesses and their managers (…) how companies revise and transform their business model in order to contribute to sustainable development.” | [73] |

| “(…) modified and completely new business models [that] can help develop integrative and competitive solutions by either radically reducing negative and/or creating positive external effects for the natural environment and society.” | [74] |

| Definition | Sources |

|---|---|

| “Generalizations of specific business models” | [43] |

| “The essence of a different way to conduct business” | [79] |

| “Business models with similar characteristics, similar arrangements of business model Building Blocks, or similar behaviors” | [36] |

| “The relationship between a certain context or environment, a recurring problem and the core of its solution” | [26] |

| “A specific configuration of the (…) business modeldimensions (...) that has proven to be successful” | [76] |

| “Reusing solutions that are documented generally and abstractly in order to make them accessible and applicable to others.” | [80] |

| “We define a business model pattern as a combination of configuration options, which repeatedly occurs in successful business models.” | [81] |

| Function | Implication |

|---|---|

| Recipe function | This is understood to mean that a company’s current business model can be used to guide business model innovations in other companies [64]. The function is not about copying the model completely, but rather about using it as a stimulus-based creativity technique. |

| Structuring function | Representation of the key similarities and differences between two or more business models [27]. |

| Identification function | The internal identification function shows whereby a company feels it belongs to a group of companies with the same business model based on the structure of the business model. The external dimension [84] has the goal of realising social acceptance, scientifically speaking, the “license to operate” or other positive attributions through identification. |

| Communication function | The business model is a narrative representation [85] of the company’s activities and, above all, of the value generation [83] vis-à-vis third parties (stakeholders), whereby, according to Doganova, Eyquem-Renault [28], these are a heterogeneous target group. |

| Analysis function | The object here is the description and classification of the business model of companies [83]. The analysis can relate both to the status quo and to the future, whereby, in this case, the business model approach, like a rapid prototyping tool [86], makes it possible to check business model innovations for their probability of success. |

| Research Steps | Goals | Procedure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Exploring the research literature on the topic of sustainable business model innovations | Indexing of all relevant sources | Search relevant sources (e.g., EconBiz or Business Source Complete) based on criteria; Development of relevant search terms; Discovery of further relevant publications through source analysis of the data material that has been indexed so far; Opening up the sources and sorting out unsuitable hits. | List of relevant sources |

| Phase 2: Creation of a taxonomy for the classification of patterns | Creation of a taxonomy | Exclusion of duplicates and patterns with no relevance for sustainability development of a taxonomy to capture the patterns. | Taxonomy that can be used to classify patterns |

| Phase 3: Creation of the database through classification of the patterns | Generating a database that unlocks unique patterns based on the output and thus enables innovation. | Transfer of all patterns into the matrix (taxonomy) based on similarities in title, description, case study companies; Use taxonomy until all patterns have been assigned. | Database of unique sustainable business model patterns |

| Search Terms Part 1 | Search Terms Part 2 | Search Terms Part 3 |

|---|---|---|

| pattern | sustainability | |

| sequence | sustainable development | |

| sustainable innovation | ||

| business modelling | ||

| business model | ||

| business model analogies [92] | ||

| atomic business models [79] | ||

| operating business models [93] |

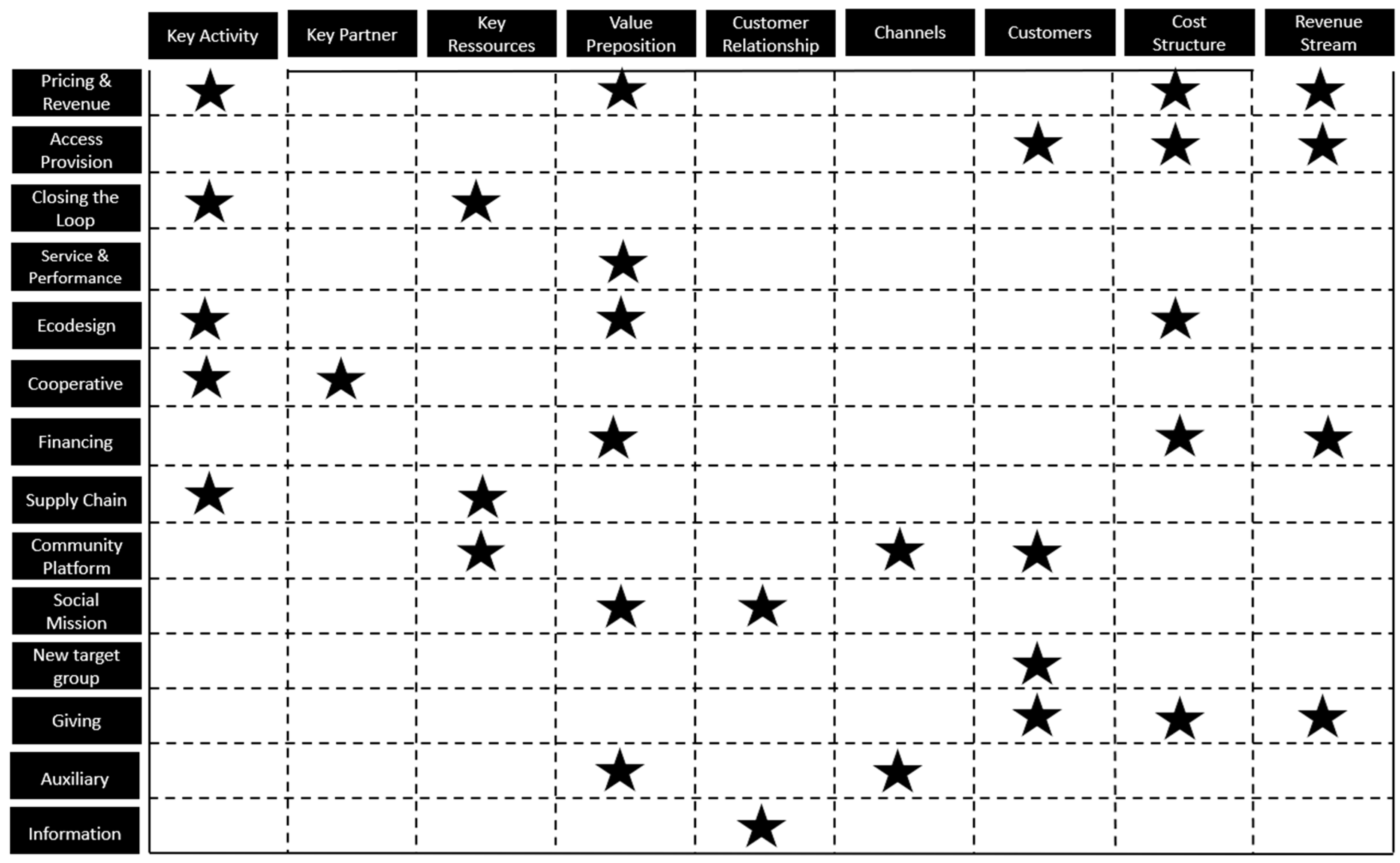

| Class Description | Outcome | Outcome Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Increase of the contribution margin through sustainability in processes and the value proposition | Rise in contribution margin | Pricing & Revenue |

| Access to a service is enabled, not its possession | More accessibility through reduced capital commitment | Access Provision |

| Minimisation of waste through recycling and reuse of products | Services whose components can be better reused | Closing the Loop |

| Services that are more sustainable than comparable competitor products | Unique selling proposition on the market | Service & Performance |

| Products are optimised for sustainability during their development process | Increasing sustainability in manufacturing | Ecodesign |

| Creation of a community from producers to make production sustainable through the optimised use of resources | Building a community | Cooperative |

| Provision of innovative financing services | Increase the target group | Financing |

| Alignment and selection of production steps and suppliers in the supply chain based on sustainability criteria | Increasing sustainability in manufacturing | Supply Chain |

| Creation of a community of users, to whom services are iteratively offered for purchase | Building a community | Community Platform |

| The economic activity results in social added value or is fully oriented towards it | Sustainability outside the direct product reference | Social Mission |

| Addressing new customer segments | Increase the target group | New Target Group |

| Those in need get access to services | Increase the target group | Giving |

| Enabling the user to make a well-informed decision based on facts regarding sustainability | Increase the target group | Information |

| Business model innovation that supports sustainability indirectly | Sustainability outside the direct product reference | Auxiliary |

| Source | Number of Relevant Patterns | Focus Area of Publication |

|---|---|---|

| [88] | 5 | None, broad focus |

| [105] | 6 | Circular Economy Business Model Patterns |

| [106] | 9 | None, broad focus |

| [107] | 7 | None, broad focus |

| [32] | 20 | None, broad focus |

| [108] | 3 | E-learning |

| [26] | 11 | E-mobility |

| [31] | 9 | S&P 500 firms |

| [33] | 6 | Smartphone life cycle |

| [87] | 8 | Sharing economy |

| [109] | 3 | Circular economy |

| [110] | 4 | Social Value |

| [111] | 7 | Social Value |

| [20] | 13 | None, broad focus |

| [112] | 3 | Circular business models for the fast-moving consumer goods industry |

| [113] | 6 | Fast-moving consumer goods |

| [114] | 5 | Fast-moving consumer goods |

| Name of the Pattern | Outcome Dimension | Description | Case Study Company | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trash-to-cash | Pricing & Revenue | Selling of used products to extract the resources contained therein and use them as a basis for new products. | Duales System Deutschland and cmr | [88] |

| Reuse and Redistribution | Pricing & Revenue | Selling of second-hand goods, whereby at most, a slight upgrading has taken place through the removal of signs of use. | Rebuy and Godsinlösen | [89,109] |

| Refurbishing and repair gap-exploiter | Pricing & Revenue | Selling of used products that have previously been significantly repaired or overhauled. | Back Market and kaputt.de | [33,105] |

| Refurbishing and WEEE service provider | Pricing & Revenue | At the end of the life cycle of an electrical appliance, it is taken back from the user within the framework of a contract concluded in advance and subjected to further recycling. | AfB Group | [33] |

| Energy Saving Companies | Pricing & Revenue | A company enables energy savings for its customer and is paid on the basis of and in relation to them. | Danfoss Solutions | [107] |

| Chemical Management Services | Pricing & Revenue | In the context of chemicals, the benefit achieved by the customer through the application of these is remunerated. | SAFECHEM | [107] |

| Freemium | Pricing & Revenue | Splitting the scope of a product into a basic functionality, which is provided free of charge, and additional services for an additional fee. | FreedomPop and TextNow | [32] |

| Pay for Success | Pricing & Revenue | The producer is paid only when his performance is successful. | Johnson & Johnson Social Finance/Collective Health | [32] |

| Robin Hood | Pricing & Revenue | Charge wealthy customers more than poorer customers for the same product or service, so that the first rich subsidize the poor. | Museums, Aravind, Eye Care | [88] |

| Differential Pricing | Pricing & Revenue | Linking the price of services to fixed criteria that use the target group’s ability to pay as a differentiating factor. | Narayana Health and Novo Nordisk | [32] |

| Reverse auction | Pricing & Revenue | Allocation of orders to the lowest bidding participant under fulfilment of given conditions. | Bundesnetzagentur | [26] |

| Negative operating cycle | Pricing & Revenue | A purchase price payment that is due upon conclusion of the contract, whereas the performance due is postponed. | traveller’s cheque | [26] |

| Product-service systems | Pricing & Revenue | Business models that integrate products and services into customer offerings that provide a product, a functionality, or a result. | apple | [20] |

| Summary: The basic concept of sustainable business models, which links sustainability directly to financial outcomes, meaning that an increase in sustainability has a direct financial impact. Sustainability thus becomes a driver of growth and return. Being a default category, the patterns have the broadest application focus and can be used in any product related to sustainability. | ||||

| Subscription Model | Access Pro-vision | The customer pays an ongoing fee to gain ongoing access to a product or service. | Better Place and Blissmobox | [32] |

| Rent instead of buy (lease instead of sell, leasing, lease) | Access Provision | Temporarily lend a product to the customer and charge a rent instead of selling it for permanent use. | Xerox, fashionette and United Rentals | [88] |

| Shared infrastructure | Access Provision | Share a common infrastructure among several competitors. | ABACUS | [88] |

| Shared Resource | Access Provision | Access to a product in a community of users is sold instead of actual ownership, with a focus on the group behaviour. | AirBnB and Fon | [32] |

| Fractionalization | Access Provision | Splitting the power of disposal of a product that is too expensive for the target group on the basis of duration of use. | Marriott International | [26] |

| Deliver functionality rather than ownership | Access Provision | Satisfying the user’s need without owning the product that delivers the service. | Hilti and Rolls Royce plc | [20,32,108] |

| Summary: The sale of a product is replaced by granting use for a fee. The sustainable impact is centred around the minimisation of produced goods through increasing the efficiency of use. The core ide is about sharing, so that the focus of applications is on expensive, but rarely used, products because transaction costs have a minor impact on them. | ||||

| Recycling | Closing the Loop | Recycling of resources from used or no longer functional products as raw material for new services. | Duales System | [20,105,106] |

| Cascading and Repurposing | Closing the Loop | Multiple use of the inherent energy of a natural energy source, such as wood. | Veolia | [105] |

| Organic Feedstock Business Models | Closing the Loop | Use of waste from food production and preparation as an energy source for processes with an exogenous energy demand. | KLM | [105] |

| Take back management | Closing the Loop | The value proposition of a product is extended to include a take-back guarantee, so that the customer has no problems when disposing of it. | Desso | [107] |

| Cradle to cradle | Closing the Loop | Products are not understood by the manufacturer as a one-time transaction, but are viewed in a holistic framework of use and recycling. | Gabriel | [107] |

| Closed-Loop Production | Closing the Loop | The waste that is generated during the production is continually recycled through capturing, reusing, or biodegrading and composting waste. | Novelis or Interface | [32] |

| Repair | Closing the Loop | Extending product life through repair and maintenance. | Agito Medica | [109] |

| WEEE service provider | Closing the Loop | Recycling and waste disposal of electrical equipment with the aim of transferring the highest possible proportion into new products and protecting the general public. | binee, take-e-way, and Closing the Loop | [33] |

| Summary: The category stands for the idea that waste should be seen as a valuable resource and, therefore, integrated in the production process rather than being disposed of. This pattern is particularly suitable for manufacturing companies. | ||||

| Functional sales and management services | Service & Performance | Integration of sustainability aspects into functional sales and management services, so that they influence the decision-making process. | Fairphone | [106] |

| Efficiency optimisation by ICT | Service & Performance | The efficiency of processes is increased through the integration of ICT technologies. | Bosch | [106] |

| Sustainable mobility systems | Service & Performance | Mobility services are provided in a way that reduces the negative impact on the environment and the community. | ubitricity | [106] |

| Physical to Virtual | Service & Performance | Physical sales infrastructure is replaced by digital sales channels, so that resource consumption is significantly reduced. | Sungevity, FreshDirect | [32] |

| Maximise material and energy efficiency | Service & Performance | Replacing physical products with digital counterparts, saving the resources of physical deployment. | Pearson | [108] |

| Unique partnerships | Service & Performance | Selling an attitude to life associated with a bundle of services to fill them. | LMVH | [26] |

| Maximise material and energy efficiency | Service & Performance | Generation of the maximum output with a given number of resources through more efficient processes. | Aurubis | [20] |

| Substitute with renewables and natural processes | Service & Performance | Replacing non-renewable resources with renewable ones and artificial processes with ones that mimic or use processes in nature. | Thyssenkrupp | [20] |

| Summary: Sustainability is considered an integral part of the value proposition of a product. To justify this, the business model is geared towards consuming fewer resources relative to a conventional counterpart. The implementation here is non-specific, as potentially all starting points in the business model can be addressed. Consequently, the field of application is hardly limited, although services are more difficult to market. | ||||

| Repair & maintenance | Ecodesign | Extending the life cycle of a product through the easy repairability, which is a design trait. | SHIFT | [105] |

| Greener product/process | Ecodesign | Sustainable design of the production process. | Dassault Systèmes | [106] |

| Design, Build, Finance, Operate | Ecodesign | Combining the financing, creation, and operation of a product into a bundle of services designed for a multi-year basis. | Allfarveg | [107] |

| Produce on Demand | Ecodesign | A service is created only if there is a dedicated purchase contract for it. | LEGO CUUSOO, Threadless | [32] |

| Rematerialization | Ecodesign | New products are created so that waste can be a relevant resource pool. | Waste Management Lehigh Technologies | [32] |

| Usage-extending distributor | Ecodesign | Production and distribution of particularly long-lasting products. | Vireo, Deutsche Telekom, and Swisscom | [33] |

| Product Design | Ecodesign | Offering products that combine one or all of the following dimensions: responsible supply chain, long life expectancy, increase users’ ecoefficiency, and are reusable, repairable, and/or recyclable. | Xella Denmark | [109] |

| Summary: The patterns describe a design and production process philosophy that is centred around the idea of resource consumption from a lifetime perspective. The overarching goal is to minimise resource consumption; therefore, it is particularly suitable for durable investment goods. | ||||

| Industrial symbiosis | Cooperative | Linking of different stages of the value chain or of companies with similar needs for the resource-efficient implementation of production processes. | Cleantech Östergötland | [106] |

| Industrial Symbiosis Industry | Cooperative | In industry, unused or underutilised resources are made available to multiple consumers, so that the efficiency of resource utilisation is increased. | Kalundborg | [107] |

| Summary: Patterns under the label “cooperative” focus on linking different companies at the same and different stages of the value chain, so that networks are created that minimise waste and time losses by optimising resource usage. The patterns are, therefore, mainly relevant for companies with expensive resource inputs. | ||||

| Buy One, Give One | Giving | Every service sold is priced in such a way that an equivalent service can be given away to those in need. | 2 Degrees TOMS Shoes | [32] |

| Summary: With “Giving”, the purchase of a product is combined with an obligatory donation for sustainable causes. Therefore, a trade-off between price and social value takes place, which determines a target group with high purchasing power. Relevant product categories have an initial low purchasing price, so that the surplus can be neglected. | ||||

| Innovative Product Financing | Financing | Implementation of innovative financing solutions for the payment of the purchase price or user fee of a service. | Simpa Networks Sungevity | [32,106] |

| Microfinance | Financing | The provision of small loans to low-income borrowers who do not have access to a traditional bank account. | WaterCredit Jamii Bora Bank | [32] |

| Crowdfunding | Financing | Financing through many comparatively small amounts raised from end consumers. | Kickstarter Fundly | [32] |

| Summary: “Financing” as a pattern deals with the question of how to raise money for companies and purposes that have no or underdeveloped access to financing. In this regard, non-traditional sources that value purpose as a part of the return are favoured. This pattern is relevant for companies and projects with no stable financing and cashflow, such as start-ups, as well as for purposes that do not generate risk-adequate returns. | ||||

| Alternative energy-based systems | Supply Chain | The exogenous process energy is obtained as sustainably as possible. | BASF | [106] |

| Green Supply Chain Management | Supply Chain | Sustainability is integrated into the supply chain, so that preliminary products are created in a socially and environmentally compatible manner. | IKEA IWAY | [33,107] |

| Inclusive Sourcing | Supply Chain | Only suppliers that meet the highest standards of sustainability and human rights are used. | Walmart Sylva Foods | [32] |

| Summary: The “Supply Chain” pattern is based on optimising the supply chain based on all three dimensions (economy, ecology, and social) of sustainability. This takes place along all upstream stages of the value chain and manifests itself, for example, through sourcing input factors with a lower carbon footprint. Yet, it is just as important to process the transactions in the value chain in a sustainable manner. The pattern is particularly suitable for large companies, as they have the same obligations imposed by the legislator and, at the same time, have the resources to ensure compliance. | ||||

| Cooperative Ownership | Community Platform | Association of consumers who jointly own, manage, and use production factors or consumer goods. | Ocean Spray The Co-operative Group | [32] |

| Collaborative community platforms | Community Platform | Platforms that implement social or environmental topics based on the joint achievements of the members. | not far from the tree | [87] |

| Niche peer-to-peer platforms | Community Platform | Intermediation of goods and services with a niche character between commercial and non-commercial suppliers and consumers, following soft or no rules. | SmartCommute, BKSY and WarmShowers | [87] |

| Niche corporate platforms | Community Platform | Intermediation of goods and services with a niche character between commercial and non-commercial suppliers and consumers, following strict rules. | FreshRents, Privateshare and Seats2Meet | [87] |

| Commercial peer-to-peer platforms | Community Platform | Intermediation of goods and services between commercial and non-commercial suppliers and consumers, following strict rules. | Poparide, reheart and Swimply | [87] |

| Peer-to-peer space sharing platforms | Community Platform | Informal mediation of areas for work and residential purposes between all possible target groups. | Airbnb, FlipKey and RoverPark | [87] |

| Peer-to-peer mobility sharing platforms | Community Platform | Brokerage of mobility services by private providers to the end consumer. | Turo, Uber and BlaBlaCar | [87] |

| Business-to-consumer mobility sharing platform | Community Platform | Brokerage of mobility services by commercial providers to the end consumer. | ZipCar, ShareNow and DropBike | [87] |

| Coworking space platforms | Community Platform | Rental of workstations in coworking spaces. | WeWork, Spaces and Impact Hub | [87] |

| Summary: “Community Platform” is a two-sided model. On the one hand, it creates value through the efficient allocation of goods and services, so that resources are used efficiently. On the other hand, companies could enter the platform economy and, consequently, could generate a monopoly earning through it. The pattern is particularly useful in markets where suppliers and consumers have little information about each other or where there is uncertainty about the quality of the service. | ||||

| Green neighbourhoods and cities | Social Mission | Increasing the sustainability of human settlements by incorporating sustainable technologies and increasing the proportion of plants in the built environment. | Grüne Nachbarschaft | [106] |

| Sufficiency-advocating network provider | Social Mission | Combination of a main service with a secondary social purpose that has no direct relation to the design of the main service. | goood | [33] |

| Two-Sided Social Mission | Social Mission | Linking companies that want to be socially active with target groups in need. | Was hab’ ich? | [110] |

| One-Sided Social Mission | Social Mission | Providing access to services that the vulnerable target group would otherwise not be able to afford. | Arbeiterkind | [110] |

| Commercially Utilised Social Mission | Social Mission | Offering a product or service for free to a social target group while earning revenue from monetising the information generated by the social target group. | co2online | [110] |

| Market-Oriented Social Mission | Social Mission | Enable labour market access for target groups with multiple employment barriers. | Fifteen | [110] |

| Micro Distribution and Retail | Social Mission | Establishment of a livelihood-securing source of income through trade for disadvantaged target groups. | Project Shakti of Hindustan Uni Lever | [111] |

| Experience-Based Customer Credit | Social Mission | Lending by non-financial market companies based on experience with the respective customer from existing business relationships. | MYbank | [111] |

| Last-Mile Grid Utilities | Social Mission | Covering the gap between households and bigger supply lines through access to financing and customer service. | Last Mile Solutions | [111] |

| Value-for-Money Housing | Social Mission | Housing that offers a combination of high value for money and facilitated access to mortgage financing for people with low income. | Housing Plus Group | [111] |

| Smallholder Procurement | Social Mission | Linking many inherently geographically remote locations into one network, so that synergies in transport, packaging, and capacity result in an attractive target group. | National Food Reserve Agency in Tanzania | [111] |

| e-Transaction Platforms | Social Mission | Reducing transaction costs by incorporating digitization, so that lower-income groups can also gain access to scarce goods. | PayPall | [111] |

| Value-for-Money Degrees | Social Mission | Enabling access to university education for low-income groups. | The Open University | [111] |

| Social enterprises | Social Mission | Businesses that have in addition or solely the goal of creating a social impact. | Aravind Eye Care | [20] |

| Repurpose for society or the environment | Social Mission | Utilising organisational resources and capabilities to create societal or environmental benefits. | Bosch Stiftung | [20] |

| Inclusive value creation | Social Mission | Delivering value to formerly unattended stakeholders or including them in the value creation process. | Unilever and Symrise | [20] |

| Summary: In the “Social Mission” pattern, a strong stakeholder orientation in the corporate goals and, consequently, in the corporate strategy is the core idea. Therefore, profit is not the first goal of companies, but rather creating a positive impact. The application focus is, therefore, broad, as almost every business model could be rearranged in a way to improve the social value. | ||||

| Micro-Franchise | New target group | Adaption of the traditional franchising concept to the poor in order to own and manage their own businesses. | Fan Milk Limited Hapinoy | [32] |

| Alternative Marketplace | New target group | Tapping previously untapped potential by using a new transaction mechanism between customer and manufacturer. | ITC e-Choupal OneMorePallet | [32] |

| Own the undesirable | New target group | Pursuing a business in seemingly unprofitable market segments. | Ryanair | [26] |

| Dial down features | New target group | Addressing target groups with comparatively low needs with appropriate services. | Dacia | [26] |

| Licensor or franchisor | New target group | Licensing of a business model for sustainable purposes. | Messe Nürnberg | [26] |

| Bottom of the pyramid solutions | New target group | Producing goods and services for customers at the bottom of the income pyramid. | Xiaomi | [20] |

| Summary: “New target group” refers to the development of new customer groups that would not have been reached without the business model. Here, the focus is on a social mission that tries to reach disadvantaged groups as customers. The pattern is, therefore, broadly applicable. | ||||

| Behaviour Change | Information | The business model is aligned to incentivize and reward customers for sustainable behaviour. | Opower Recyclebank | [32] |

| Adopt a stewardship role | Information | Protecting natural systems by introducing a gatekeeper who controls access or incentivizes and, therefore, moderates certain behaviours. | National Park Service (USA) | [20] |

| Encourage sufficiency | Information | Providing information and incentives that encourage less consumption. | RESET—Digital for Good | [20] |

| Summary: The patterns of the “Information“ group aim to enable customers to make an informed decision regarding consumption, so that a nagging approach towards behaviour change can be implemented. The application horizon is broad, with a focus on a market where several products are substitutes relative to each other. | ||||

| Develop scale-up solutions | auxiliary | Breaking up the traditional relationship between customer and producer through the use of digital tools. | Amazon | [108] |

| Reverse razors/blades | auxiliary | Consumables are exchanged between different main products. | Canon Printer or Apple Music | [26] |

| Develop sustainable scale up solutions | auxiliary | Scaling up sustainable solutions and technologies. | Impact Hub Ruhr | [20] |

| Multi-sided platform | auxiliary | A platform that brings suppliers and buyers together and thus facilitates transactions. | eBay | [26] |

| Unbundling the business model | auxiliary | A provider focuses on one value step or need. | Blau.de | [26] |

| Bundling | auxiliary | Bundling of several different services from one or more providers into a single service block, so that the consumer can choose the fitting option and, therefore, consume less. | [26] | |

| Summary: With regards to “auxiliary”, patterns are to be applied broadly, as they do not aim directly at increasing sustainability. Rather, they provide support and a competitive advantage for sustainable business models, so that the negative effects of more sustainability, such as higher costs, can be compensated for, and the service becomes marketable. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schroedel, S. The Sustainable Business Model Database: 92 Patterns That Enable Sustainability in Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108081

Schroedel S. The Sustainable Business Model Database: 92 Patterns That Enable Sustainability in Business Model Innovation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108081

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchroedel, Sebastian. 2023. "The Sustainable Business Model Database: 92 Patterns That Enable Sustainability in Business Model Innovation" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108081

APA StyleSchroedel, S. (2023). The Sustainable Business Model Database: 92 Patterns That Enable Sustainability in Business Model Innovation. Sustainability, 15(10), 8081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108081