The Effect of Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices on Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Institutional Performance in Hotel Businesses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relationship among Sustainable HRM Practices and Service Quality

“Are the sustainable HRM practices positively connected to the growth of quality of service in hotel sector?”

2.2. Relationship among Customer Happiness and Service Quality

“Is there any correlation between service quality and customer happiness in hotel sector?”

2.3. Relationship among Sustainable HRM Practices and Company Performance

“Does institutional performance correlate in any way with sustainable HRM practices?”

2.4. Relationship among Sustainable HRM Practices, Service Quality, Customer Happiness, and Company Performance

“Are sustainable HRM practices, customer satisfaction, service quality and hotel company performance related?”

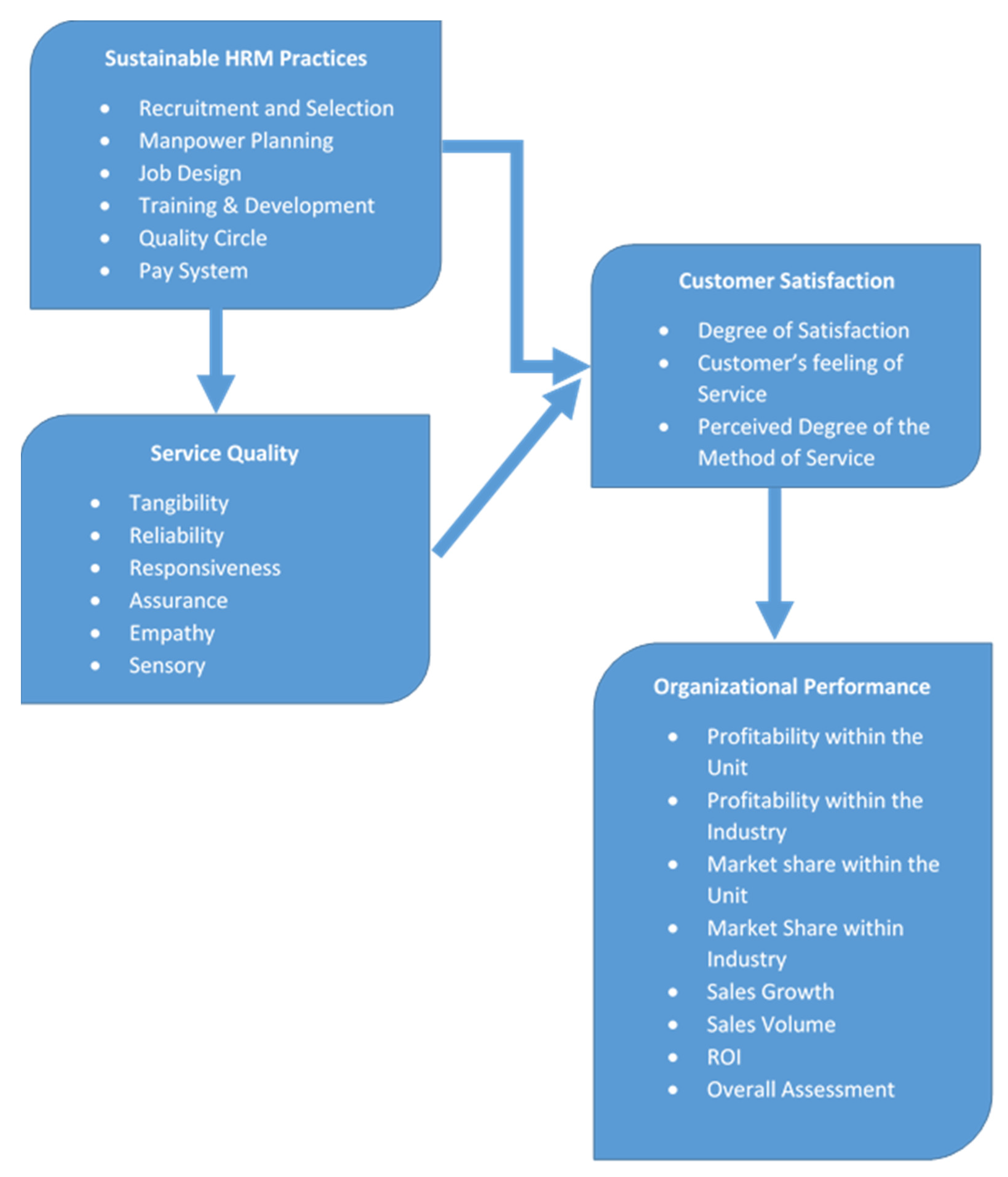

3. Theoretical Model

4. Methodology

4.1. Measure Development

4.2. Statistical Hypotheses

4.3. Statistical Methodology

5. Analysis and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Invest Cyprus. 2022. Available online: https://www.investcyprus.org.cy/tourism-and-hospitality/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Kramar, R.R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Stankevi, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Raising the Curtain in People Management by Exploring How Sustainable HRM Translates to Practice: The Case of Lithuanian Organizations. Sustainbility 2018, 10, 4356. [Google Scholar]

- Hartline, M.D.; Jones, K.C. Employee Performance of a Hotel Service Environment: Influence on Perceived Service Customer Value and Word-of-Mouth Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 35, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, A.; Khan, D. Frontline service employees and customer engagement: Some further insights. IIM Ranchi J. Manag. Studies 2022, 1, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, K. Labour Ministry Initiative Fails to Dent Hotel Staff Shortages. Available online: https://cyprus-mail.com/2022/02/12/labour-ministry-initiative-fails-to-dent-hotel-staff-shortages/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hartline, M.D.; Ferrell, O.C. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.W.; Hoffman, K.D. An Investigation of Proposed Affect, Pro-social Behaviour and Service Quality. J. Retaining 1997, 73, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H. Customer Service. 2021. Available online: https://roicallcentersolutions.com/customerservice/why-is-professionalism-important-in-customer-service/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Saini, D.; Budhwar, P. Human Resource Management in India, in Managing Human Resources in Asia-Pacific; Budhwar, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar]

- Naresh, K.; Budhwar, P.S. A study of strategic HR issues in an Asian context. Pers. Rev. 2002, 31, 166–188. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, M.; Katou, A. The Impact of HRM Practices of Organisational Performance in Indian Hotel Industry. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2007, 29, 576–594. [Google Scholar]

- Chieng, H.P.; Arokiasamy, L.; Kassim, K.A.A. Human resource management practices and their impact on construction institutional performance. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 1, 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, M.; Ganie, S.; Ganaie, M.; Saleem, I.; Khan, I.S. Human Resource Management Practices and Institutional Performance: The Mediating Role of Team Competence. In Proceedings of the First Pan IIT International Management Conference, Roorkee, India, 30 November–2 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.; Abdulla, N.N. The impact of Human resource management practice on Institutional performance. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2021, 5, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, F.; Jusoh, J. Service Quality in Penang Hotels: A Gap Score Analysis. World Appl. Sci. J. 2011, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mamilla, R.; Janardhana, G.; Anjan, B.G. Customer Satisfaction on Reliability Dimension of Service Quality in Indian Higher Education. Int. J. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2013, 7, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S. Corporate Image and Customer’s Satisfaction Towards Customers Perception: An Exploratory Study on Telecom Customers in Bangladesh. Bus. Intell. J. 2012, 5, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dortyol, I.T.; Varinli, I.; Kitapci, O. How do international tourists perceive hotel quality? An exploratory study of service quality in Antalya tourism region. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 470–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, K.; Mani, B.T.; Kumar, S.A.; Prabhakaran, S. Prabhakaran. Influence of service quality on customer satisfaction application of servqual model. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H. Performance Management; Pearson/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Papademetriou, C. International Human Resource Management: Sequential Cross Cultural Training–Sociocultural and Psychological Adjustment; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-53616-947-8. [Google Scholar]

- Apornak, A. Customer satisfaction measurement using SERVQUAL model, integration Kano and QFD approach in an educational institution. Int. J. Product. Qual. Manag. 2020, 21, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, B.Y.; Abdallah, A.B. The Relationships among Human Resource Management Practices, Organizational Commitment, and Knowledge Management Processes: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyin, N.; Dainty, A.; Carrillo, P. HRM strategies for managing employee commitment: A case study of small construction professional services firms. In Proceeding of the Engineering Project Organizations Conference, Rheden, The Netherlands, 10–12 July 2012; pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ijigu, A.W. The Effect of Selected Human Resource Management Practices on Employees’ Job Satisfaction in Ethiopian Public Banks. EMAJ Emerg. Mark. J. 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, N.; Harb, A.; Shrafat, F.; Alhusban, M. The effect of organizational culture on the organizational commitment: Evidence from hotel industry. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, E.; Redman, T. HRM practices, organizational citizenship behaviour, and performance: A multi-level analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, L.A.; Heskett, J.L. The service-driven service company. Harward Bus. Rev. 1991, 69, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. HRM–A Service Perspective: Towards a Customer-focused HRM. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1994, 5, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Lin, Y.C. Promoting service quality in tourist hotels: The role of HRM practices and service behavior. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultlten, Y.; Muluk, Z. The practice of service quality: Hotel case. Glob. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Curr. Issues 2016, 6, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tiago, F.; Borges-Tiago, T.; Couto, J. Human resources role in hospitality service quality. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 8189. [Google Scholar]

- Mohinder, C. Human Resource Strategies and Global Competitiveness: A Study of Indian Small and Medium Sized Tourism Enterprises. In International Conference on Creating Global Competitive Advantage; Laxpara Foundation: Shimla, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Belias, D.; Vasiliadis, L.; Mantas, C. The human resource training and development of employees working on luxurious hotels in Greece. Cult. Tour. Innov. Digit. Era 2020, 639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Tornow, W.W.; Wiley, J.W. Service Quality and Management Practices: A Look at Employee Attitudes, Customer Satisfaction, and Bottom-Line Consequences. Hum. Resour. Plan. 1991, 14, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, T.K. The Impact of Human Resource Practices on Service Performance of Taiwanese Hotel Industry: Organizational Commitment as a Mediator. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Logist. Manag. 2006, 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, U.; Kura, K.M.; Umrani, W.A.; Pahi, M.H. Modelling the Link Between Developmental Human Resource Practices and Work Engagement: The Moderation Role of Service Climate. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 2, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folinas, D.K.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Coudounaris, D.N. Just-in-time theory: The panacea to the business success? Int. J. Value Chain. Manag. 2017, 8, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C. Establishment of a quality-management system for service industries. Total Qual. Manag. 2006, 17–19, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The Swedish Experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, N.T.; Chovancová, M.; Tri, H.T. The impact of E-service quality on the customer satisfaction and consumer engagement behaviors toward luxury hotels. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnjo, E.; Rudy, R.; Simamora, S.; Hutabarat, L.R.; Juliana, J. Identifying Customer Behavior in Hospitality To Deliver Quality Service And Customer Satisfaction. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Res. 2021, 2, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Service quality, profitability, and the economic worth of customers: What we know and what we need to learn. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Teeroovengadum, V.; Ringle, C.M.; Sunnassee, V. Service quality and customer satisfaction: The moderating effects of hotel star rating. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Hubbert, A.R. Encounter Satisfaction versus Overall Satisfaction versus Service Quality: The Consumer’s Voice. In Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Rust, R.T., Oliver, R.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oak, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 72–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. The relationship among marketing mix, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty of Chinese tourists to budget hotel of central Bangkok. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hansemark, O.C.; Albinsson, M. Customer satisfaction and retention: The experiences of individual employees. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 14, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, S.; Fotiadis, T.; Anastasiadis, L.; Iakovidis, G.; Fotiadou, X.; Tiliakou, C. Estimate and analysis of vocational training school (IEK) students’ satisfaction regarding the quality of studies provided by these schools. Sci. Bull. Econ. Sci. 2016, 15, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Belias, D.; Rossidis, G.; Papademetriou, C.; Mantas, C. Job Satisfaction as Affected by Types of Leadership: A Case Study of Greek Tourism Sector. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 23, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Berchoux, C.; Marek, M.W.; Chen, B. Service quality and customer satisfaction: Qualitative research implications for luxury hotels. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunniwo, F.; Hsu, M.K.; Udo, G.J. Service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in the service factory. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.F.; Saadan, K.B.; Seman, K.B. Determining the Influence of the Reliability of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction: The Case of Libyan ECommerce Customers. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2015, 5, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, M.; Michalkova, A. Monitoring Customer Sstisfaction in Service Industry. Kval. Inovacia Prosper. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2012, 16, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, K.-J.; Lee, J.-S. Country Club Members’ Perceptions of Value, Image Congruence, and Switching Costs: An Exploratory Study of Country Club Members’ Loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Wisenblit, J.L. Consumer Behavior, 11th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E.; Bakker, A.B. Positive Emotions: The Connection between Customer Quality Evaluations and Loyalty. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2011, 52, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, I.; Tesic, Z.; Kuzmanovic, B.; Tomic, M. An empirical study of employee loyalty, service quality, cost reduction and company performance. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2018, 31, 827–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katou, A.; Budhwar, P. Human Resource Management Systems and Institutional performance: A Test of a Mediating Model in the Greek Manufacturing Context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1223–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, M. The impact of HRM practices on service quality, customer satisfaction and performance in the Indian hotel industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Brown, A. HRM Strategies and Labour Turnover in the Hotel Industry: A Comparative Study of Australia and Singapore. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 9, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, P.; Fryer, G. Human Resources, Service Quality and Performance: A Case Study. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, A. Innovative Human Resource Management and Corporate Performance in the Context of Economic Liberalization in India. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1278–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarello, S.; Filippini, R.; Nosella, A. Linking human resource management practices and customer satisfaction on product quality. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3906–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examina-tion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, J.L.; Sasser, W.E.; Schlesinger, L.A. The Service Profit Chain; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdi, B.; Alshurideh, M.; Alnaser, A. The impact of employee satisfaction on customer satisfaction: Theoretical and em-pirical underpinning. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3561–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, G.; Watson, S.; Quail, S. Quality Service in the International Hotel Sector: A Catalyst for Strategic Human Resource Development. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2004, 28, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, M.V.; Hancer, M. Using the Social Exchange Theory to Explore the Employee-Organization Relationship in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 670–692. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, B.; Gerhart, B. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Organizational Performance: Progress and Prospects. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N. Management Human Resource for Competitive Advantage: A Study of Companies in Singapore. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 336–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyju, P.J.; Singh, K.; Kokkranikal, J.; Bharadwaj, R.; Rai, S.; Antony, J. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism: An Assessment of Research in Web of Science. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 24, 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, D. Managing Employee Relations through Strategic Human Resource Management: Evidence from Two Tata Companies. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2006, 42, 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Belias, D.; Rossidis, I.; Papademetriou, C.; Lamprinoudis, N. The Greek hotel sector: An analysis of job satisfaction, role conflict and autonomy of Greek employees. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 21, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Chung, K. Measuring customer satisfaction and hotel efficiency analysis: An approach based on data envelopment analysis. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 63, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity and Corporate Financial Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najam, U.; Ishaque, S.; Irshad, S.; Salik, Q.U.A.; Khakwani, M.; Liaquat, M. A link between human resource manage-ment practices and customer satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parahoo, Μ.K. Nursing Research: Principles, Process and Issues, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan Methodology: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.J.; Black, C.W.; Badin, N.J.; Anderson, E.R.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczynski, A. Quantitative limits to qualitative engagements: GIS, its critics, and the philosophical divide. Prof. Geogr. 2009, 61, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, D.; Faria, D.; Almeida, F. Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2017.

- Creswell, J.W.; Design, R. Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches; Sage Publication Inc.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Welman, J.C.; Kruger, S.J. Research Methodology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa; Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 5th ed.; John Wily and Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. The Basics of Social Research, 3rd ed.; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, J.Y. A Short Guide to Research Writing in The Social Science and Education; Ghana Universities Press: Accra, Ghana, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications forfuture research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D.W.; Lamb, C.W. An Evaluation of the SERVQUAL Scale in a Retailing Setting. Adv. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 483–490. Available online: http://www.acrwebsite.org/search/view-conference-proceedings.aspx?Id=7137 (accessed on 9 February 2015).

- Lewis, B.R. Managing Service Quality. In Managing Quality, 5th ed.; Dale, B.G., Van der Wiele, T., Van Iwaarden, J., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 234–258. [Google Scholar]

- Maylor, H. Part Three: Functional Management in Tourism: Strategic Quality Management. In Strategic Management in Tourism; Moutinho, L., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, B.G.; Van der Wiele, T.; Van Iwaarden, J. Managing Quality, 5th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.K.; Gupta, G. Measuring Service Quality: SERQUAL vs. SERVPERF. Scales Vikalpa 2004, 29, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltrop, J. The impact of human resource management on institutional performance: Theory and research. Eur. Manag. J. 1996, 14, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.A.; Canavos, G.C. Investigating the relationship between employee satisfaction and guest satisfaction. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2000, 41, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Park, K.H.; Park, D.H.; Lee, K.A.; Kwon, Y.J. The Relative Impact of Service Quality of Service Value, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Korean Family Restaurant Context. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2005, 6, 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, R.K. Mapping service quality in hospitality industry: A case through SERVQUAL. Asian J. Manag. 2017, 8, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, A.; Mostafiz, M.I.; Taniguchi, M. Using SERVQUAL to determine Generation Y’s satisfaction towards hoteling industry in Malaysia. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpikul, A. Acquiring an in-depth understanding of assurance as a dimension of the SERVQUAL model in regard to the hotel industry in Thailand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedence and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Yoo, D.K. The Determinants of Perceived Service Quality and its Relationship with Satisfaction. J. Serv. Mark. 2000, 14, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, A.T.; Zeriti, A. Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tour. Manag. 2013, 23, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Jang, E. Measuring the Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Hospitality Firms’ Performances. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croanbach, L.J. Essentials of Psychological Testing, 4th ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Kimmel, S.K. A comparison of leading theories for the prediction of directed behaviors. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS: Structural Equations Program Manual; BMDP Statistical Software: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. Mis Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures for marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreskog, K.G.; Sordom, D. Lisrel 8: User’s Reference Guide; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schene, A.; Wijngaarden, B.; Koeter., M. Family Caregiving in Schizophrenia: Domains, Distress. Schizophr. Bull. 1998, 24, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Applied Multivariate Techniques; John Willey & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Summated Rating Scale Construction: An Introduction; Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Application in the Social Sciences; SAGE: Thousand Oak, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vivilaki, V.G.; Dafermos, V.; Daglas, M.; Antoniou, E.; Tsopelas, N.D.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Brown, J.B.; Lionis, C. Identifying intimate partner violence (IPV) during the postpartum period in a Greek sample. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010, 13, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivilaki, V.G.; Dafermos, V.; Patelarou, E.; Bick, D.; Syngelaki, A.; Tsopelas, N.D.; Bitsios, P.; Petridou, E.T.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Lionis, C. Maternal screening for early postnatal vulnerability. Psychiatriki 2016, 27, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakis, M.K.; Papadopoulos, F.C.; Beratis, I.; Michelakos, T.; Kanavidis, P.; Dafermos, V.; Tousoulis, D.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Petridou, E.T. Validation of TICS for detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment among individuals characterized by low levels of education or illiteracy: A population-based study in rural Greece. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017, 31 (Suppl. S1), 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patelarou, A.E.; Dafermos, V.; Brokalaki, H.; Melas, C.D.; Koukia, E. The evidence-based practice readiness survey: A structural equation modeling approach for a Greek sample. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J. Effect of CSR activities on meaningfulness, compassion, and employee engagement: A sense-making theoretical approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Lehmann, C.F.D.R. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapouna, V.; Dafermos, V.; Chatziarsenis, M.; Vivilaki, V.; Bitsios, P.; Schene, A.H.; Lionis, C. Assessing the burden of caregivers of patients with mental disorders: Translating and validating the involvement evaluation questionnaire into Greek. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2013, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.E.; Clark, A.E.; Georgellis, Y.; Diener, E. Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Hwan, S. Relationships among service quality, customer satisfaction and profitability in the Taiwanese banking industry. Int. J. Manag. 2005, 22, 635. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, J.M.; Lynch, J.G. Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behaviour. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.; Avis, M. Construct creation from research questions. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 1817–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rasool, A. Customer engagement in the service context: An empirical investigation of the construct, its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, S. Comparison of Contemporary Advanced Statistical Methods Regarding Construct Validity Evaluation of Teique-SF Instrument: Statistical Implicative Analysis vs. Principal Components Analysis; 9ème Colloque International sur Analyse Statistique Implicative (ASI 10): Belfort, France, 2019; pp. 148–163. [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, R. CHIC: Cohensive Hierarchical Implicative Classification. In Studies in Computational Intelligence (SCI); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, R.R.; Pazmin, Ô. Statistical Implicative Analysis for Educational Data Sets: 2 Analysis with RCHI. In Proceedings of the XVIII Congreso Internacional EDUTEC Educación Y Tecnología Desde Una Visión Transformadoraedudec, Riobamba, Ecuador, 17–19 November 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, C.K. Research Methodology, Methods & Techniques; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vivilaki, V.G.; Dafermos, V.; Kogevinas, M.; Bitsios, P.; Lionis, C. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Translation and validation for a Greek sample. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, E.; Ioannidi-Kapolou, E.; Daglas, M.; Vivilaki, V.; Karamitros, D.; Dafermos, G.; Iatrakis, V. Abuse assessment screen (AAS) questionnaire: The Greek validation. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 37, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souravlas, S.; Anastasiadou, S. Pipelined Dynamic Scheduling of Big Data Streams. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Anastasiadou, S.; Katsavounis, S. More on Pipelined Dynamic Scheduling of Big Data Streams. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Anastasiadou, S.; Katsavounis, S. A Survey on the Recent Advances of Deep Community Detection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Katsavounis, S.; Anastasiadou, S. On Modeling and Simulation of Resource Allocation Policies in Cloud Computing Using Colored Petri Nets. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Anastasiadou, S.D.; Tantalaki, N.; Katsavounis, S. A Fair, Dynamic Load Balanced Task Distribution Strategy for Heterogeneous Cloud Platforms Based on Markov Process Modeling. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 26149–26162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Roumeliotis, M. Petri net modeling and simulation of pipelined redistributions for a deadlock-free system. Cogent Eng. 2015, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. Longitudinal Research; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Souravlas, S.; Anastasiadou, S.D.; Economides, T.; Katsavounis, S. Probabilistic Community Detection in Social Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 25629–25641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlas, S.; Katsavounis, S. Scheduling Fair Resource Allocation Policies for Cloud Computing through Flow Control. Electronics 2019, 8, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Eigen Value | Variance % | Lonadings | Communalities | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMR | 87.972 | 0.968 | |||||

| A. Recruitment and Selection (Recru) | 7.481 | 26.908 | 0.871 | 0.927 | 0.679 | ||

| Recru1. Harmonized and term conditions | 0.881 | 0.786 | |||||

| Recru2. Single status for all staff | 0.834 | 0.703 | |||||

| Recru3. Internal promotion norm | 0.832 | 0.697 | |||||

| Recru4. Employment test criteria | 0.817 | 0.658 | |||||

| Recru5. Merit element in selection | 0.797 | 0.652 | |||||

| Recru6. Multi-skilling and experience | 0.780 | 0.618 | |||||

| B. Manpower Planning (Manpo) | 3.865 | 19.705 | 0.901 | 0.946 | 0.813 | ||

| Manpo1. Formal manpower planning | 0.918 | 0.862 | |||||

| Manpo2. Work culture | 0.911 | 0.802 | |||||

| Manpo3. Career planning | 0.904 | 0.793 | |||||

| Manpo4. Involvement of all departments | 0.873 | 0.736 | |||||

| C. Job design (Jobd) | 3.396 | 16.023 | 0.891 | 0.927 | 0.761 | ||

| Jobd1. Flexible job description | 0.912 | 0.809 | |||||

| Jobd2. Development of learning organization | 0.874 | 0.792 | |||||

| 3Jobd. Cross-cultural job design | 0.853 | 0.761 | |||||

| Jobd4. Team working | 0.849 | 0.709 | |||||

| D. Training and development (Train) | 1.307 | 11.913 | 0.897 | 0.932 | 0.775 | ||

| Train1. Need based training and development criteria | 0.875 | 0.803 | |||||

| Train2. Formal system induction | 0.901 | 0.807 | |||||

| Train3. Learning organization | 0.843 | 0.781 | |||||

| Train4. Formal training and development | 0.901 | 0.807 | |||||

| E. Quality circle (Qcircle) | 0.447 | 7.931 | 0.906 | 0.940 | 0.798 | ||

| Qcircle1. Staff involvement in objective setting | 0.905 | 0.783 | |||||

| Qcircle2. Production/ service staff responsible for their service | 0.914 | 0.811 | |||||

| Qcircle3. Employee’s involment in quality circles | 0.923 | 0.827 | |||||

| Qcircle4. Regular use of attitudes surveys | 0.827 | 0.762 | |||||

| F. Pay System | 0.211 | 5.492 | 0.848 | 0.947 | 0.782 | ||

| Pay1. Staff informed about market condition and company performance | 0.912 | 0.802 | |||||

| Pay2. Merit element in pay package | 0.816 | 0.712 | |||||

| Pay3. staff Formal appraisal for all staff | 0.928 | 0.832 | |||||

| Pay4. No-financial incentives | 0.897 | 0.793 | |||||

| Pay5. Social appreciation and recognition | 0.864 | 0.721 |

| Construct | Eigen Value | Variance % | Loadings | Commu-n Alities | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERVQUAL | 92.931 | 0.882 | |||||

| A. Tangibles (TANG) | 7.865 | 28.983 | 0.903 | 0.946 | .854 | ||

| TANG1. This hotel haw up-to-date equipment | 0.908 | 0.895 | |||||

| TANG2. This hotel’s physical facilities are visually appealing | 0.921 | 0.903 | |||||

| TANG3. This hotel’s employees are well dresses and appear neat | 0.943 | 0.923 | |||||

| B. Reliability | 6.059 | 19.620 | 0.877 | 0.930 | .817 | ||

| TANG1. When this hotel promises to do something by a certain time, it does so | 0.934 | 0.916 | |||||

| TANG2. This hotel keeps its records accurately | 0.943 | 0.918 | |||||

| TANG3. This hotel provides its services at the time it promises to do so | 0.830 | 0.888 | |||||

| C. Responsiveness (RESP) | 5.292 | 13.459 | 0.831 | 0.941 | .842 | ||

| RESP1. This hotel does tell consumers exactly when services will be performed | 0.923 | 0.896 | |||||

| RESP2. This hotel’s employees are always willing to help customers | 0.918 | 0.870 | |||||

| RESP3. This Hotel’s emploeeys respond to customer requests promptly | 0.912 | 0.856 | |||||

| D. Assurance (ASSUR) | 4.934 | 12.568 | 0.805 | 0.964 | .898 | ||

| ASSUR1. I can trust employees of this hotel | 0.954 | 0.923 | |||||

| ASSUR2. This hotel’s employees know well their jobs to help customers | 0.935 | 0.915 | |||||

| ASSUR3. This hotel’s employees get adequate support from this restaurant to do their jobs well | 0.954 | 0.923 | |||||

| E. Empathy (EMP) | 3.756 | 11.398 | 0.811 | 0.936 | 0.831 | ||

| EMP1. Employees of this hotel know what my needs are | 0.912 | 0.887 | |||||

| EMP2. This Hotel has my best interests at heart | 0.923 | 0.902 | |||||

| EMP3. This hotel has operating hours convenient to all their customers | 0.899 | 0.876 | |||||

| F. Sensory Sensory (SEN) | 3.158 | 6.903 | 0.808 | 0.953 | 0.910 | ||

| SEN1. in its presentation This hotel serves quality food with a high degree of excellence | 0.954 | 0.903 | |||||

| SEN2. This hotels food is consistently served in the freshest state and with un uncommon degree of visual and olfactory appeal | 0.954 | 0.903 |

| Construct | Eigen Value | Variance % | Loadings | Commu-n Alities | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel Performance (PERFO) | 11.614 | 79.403 | 0.824 | 0.973 | 0.817 | ||

| PERFO1. I am satisfied regarding Profitability compared to business unit objectives | 0.912 | 0.834 | |||||

| PERFO2. I am satisfied regarding Profitability compared to hotel industry average | 0.912 | 0.834 | |||||

| PERFO3. I am satisfied regarding Market share compared to business unit objectives | 0.912 | 0.834 | |||||

| PERFO4. I am satisfied regarding Market share compared to major competitor | 0.845 | 0.783 | |||||

| PERFO5. I am satisfied regarding Market share compared to hotel industry average | 0.906 | 0.821 | |||||

| PERFO6. I am satisfied regarding Sales volume compared to business unit objectives | 0.906 | 0.821 | |||||

| PERFO7. I am satisfied regarding Return on investment compared to hotel industry average | 0.917 | 0.841 | |||||

| PERFO8. I am satisfied regarding Overall assessment of your company’s performance compared to hotel industry average | 0.917 | 0.841 |

| Construct | Eigen Value | Variance % | Loadings | Commu-n Alities | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Satisfaction (SAT) | 5.209 | 79.871 | 0.896 | 0.920 | 0.793 | ||

| SAT1. I am satisfied foe the decision that he/she patronizes the hotel | 0.837 | 0.752 | |||||

| SAT2. I am satisfied with the degree of a customer’s feeling of service | 0.916 | 0.872 | |||||

| SAT3. I am satisfied with the degree of the perceived degree of the method | 0.916 | 0.872 |

| Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRM | SERVQUAL | PERFORMANCE | SATISFACTION | ||

| HRM | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.831 ** | 0.893 ** | 0.905 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | |

| SERVQUAL | Pearson Correlation | 0.831 ** | 1 | 0.833 ** | 0.907 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | |

| PERFORMANCE | Pearson Correlation | 0.893 ** | 0.833 ** | 1 | 0.981 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | |

| SATISFACTION | Pearson Correlation | 0.905 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.981 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papademetriou, C.; Anastasiadou, S.; Papalexandris, S. The Effect of Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices on Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Institutional Performance in Hotel Businesses. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108251

Papademetriou C, Anastasiadou S, Papalexandris S. The Effect of Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices on Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Institutional Performance in Hotel Businesses. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108251

Chicago/Turabian StylePapademetriou, Christos, Sofia Anastasiadou, and Stylianos Papalexandris. 2023. "The Effect of Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices on Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Institutional Performance in Hotel Businesses" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108251